Following the surrender of German forces at the end of World War Two nearly one million captured German soldiers had their status downgraded from Prisoners of War (POWs) to Disarmed Enemy Forces. The purpose was to provide the Allied force with a ready supply of slave labor by skirting around the Geneva Convention. In Denmark, under the direction of the British, two thousand soldiers were forced to clear mines along the west coast in violation of International laws prohibiting the use of captured soldiers for dangerous jobs. Half of these veterans were killed or maimed. Roughly 300 were children, drafted near the end of the war. This is their story.

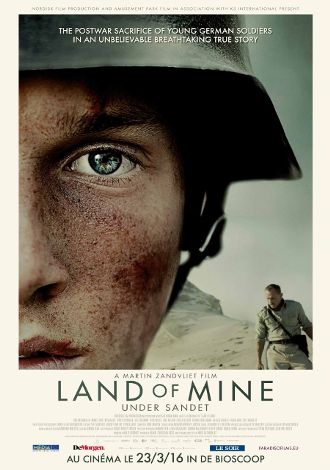

Directed by Martin Zandvliet, Land of Mine is the Danish entry for Best Foreign Film in the upcoming Academy Awards. I despise the Oscars, but even I might take a peek to see if it wins. Nordisk Film claims their standard for Oscar entries is that it must be cinema with high cultural value to the Nordic countries, and in this effort they certainly succeeded. It is one of the most moving war dramas I’ve seen.

Directed by Martin Zandvliet, Land of Mine is the Danish entry for Best Foreign Film in the upcoming Academy Awards. I despise the Oscars, but even I might take a peek to see if it wins. Nordisk Film claims their standard for Oscar entries is that it must be cinema with high cultural value to the Nordic countries, and in this effort they certainly succeeded. It is one of the most moving war dramas I’ve seen.

The film opens with Sgt. Carl Leopold Rasmussen sitting alone in his jeep, observing hundreds of captured soldiers on the long march to a prison camp in Southern Jutland for a three-day course on how to neutralize mines. Not content with their unconditional surrender Sgt. Rasmussen drives along the shuffling line of defeated Germans until he spots one carrying a folded Danish flag. He snatches it from the soldier and delivers a head butt that drops the exhausted man to the ground. Daring the others to intervene he begins to pummel the young man’s face into burger. When another of the captured begs for him to stop he too is subjected to punches and a few stomps on the ground. Rasmussen is a hard man, and this is your introduction to what he is capable of. He is, though, a soldier. True to that nature he has a begrudging respect of the martial abilities of the defeated he is ordered to train and command. At times you will admire him. Most times you will hate this man. He is a bitter and conflicted human being that has suffered the torments of war. A patriot to a land invaded who has learned that the battles are far from over.

In the prison camp they are put under the charge of Lt. Ebbe – a sadist. He assembles them in a small hangar for training. Lt. Ebbe stares at the now interned soldiers. They’re children. Teenage kids that are later described as “boys who cry for their mothers when they get scared.” It’s an accurate assessment. Told that Denmark is no friend of theirs they are set to the task of disarming and digging up mines with their bare hands. He shows them the Tellermine 42 (T.Mi.42), the most common mine used in the German defense of the beaches. German High Command believed that when the Allied forces invaded they’d be crawling up the shores of Denmark rather than Normandy. As a result there were more mines buried along that coast then in the rest of continental Europe. When asked who recognizes the mine half a dozen raise their hands. When asked who has attempted to disarm one only a couple put their arms up. Training in the sand and rain with disarmed mines Lt. Ebbe corrects each mistake with a swift wrap across the knuckles with a switch. Graduation involved taking an armed mine into a barracks reinforced by hundreds of sand bags and disarming it by hand. Those that survive this stage would be put to work on the western beaches of Denmark where an estimated 2.2 million anti-tank and anti-personnel mines lay buried.

Moving on from their training they are put under the charge of Sgt. Rasmussen. He will oversee their work on the beach. Our characters are all young, handsome German boys. Fighters who’ve never known the touch of a woman. There’s the bright-eyed leader, the stubby nosed red head who always wears his helmet, and then, of course, the twins. Some laugh. Many cry. All have dreams they rely on to carry them through this nightmare.

He lines them up in formation and demands their names. When he approaches the twins one makes the mistake of answering for the both of them. He’s told to keep quiet. Trying to be polite or diplomatic at the least he simply says “Pardon me.” This is returned with a slap to the face. “I do not PARDON!” the Sergeant informs him. He’s not a man who has sympathies that can be played upon.

Equipped only with a thin metal rod they inch across the sands stabbing into the ground until they hear the heart stopping sound of metal on metal. They dig out these hidden machines of destruction by scooping away handfuls of earth and, under threat of imminent death, dismantle the component parts and render them neutral. They are required to take the mine off the beach for disposal. In order to secure their release in three months, each soldier is informed they must disarm and remove six mines an hour. There are an estimated forty-five thousand in the portion of land they are tasked with clearing.

During their down time they fantasize about the world they will return to. The shops, cafes, and industries they will go back to rebuild. A young mother lives at the farm house nearby and we see one of the twins try to befriend her little girl only to swipe a half loaf of bread from her wagon. Their captors have begun to starve them slowly, and now the boys must face the challenge of disarming mines while extremely malnourished. They steal animal feed tainted by rat feces, and Sgt. Rasmussen discovers them sick in their barracks. He forces them to drink sea water to induce vomiting and hoses them off. Their requests for basic food were met with nothing but disdain. They begin to work on new explosives. There are stock mines sticking out of the tide, sitting on their wooden stakes waiting for the battle that never came. Even the notorious Bouncing Betty makes an appearance. As soon as I see it I pray I won’t see one of them take out any of these kids.

The German S-Mine (Schrapnellmine, Springmine or Splittermine in German) is a spring loaded anti-personnel explosive that hops one meter out of the ground before it ignites and turns the immediate vicinity into a cuisinart. Arms and legs are torn off. Often genitals as well. You don’t always die right away. You will probably wish you did while you lay helpless waiting for your eyesight to return as the ringing in your ears subsides and you can make out the muffled wailing of the man you ate breakfast with. It was the American G.I.’s that gave it the moniker we know it by in the states. Bouncing Betty. One dance would be your last.

When their desperate state of starvation and sickness begins to slow down the mine removal program they are fed. But not before that deprivation costs lives on the sand. You know that you are going to have to watch kids die in this film. That’s what happened, after all. It’s not something unique to Denmark either. France alone forced tens of thousands of German soldiers to sweep minefields and around 1800 of them died. But in Denmark we know of three hundred boys sent to those beaches. Many are represented among the thousand post-war German casualties that occurred in that country when they tried to clear the ordinance from those shores. This story follows fourteen hopeful German youths aching for a future. One is lost in training. You didn’t really see it happen though. This time you’re going to have to watch what a landmine can do to a teenage boy. When you’re in a minefield you cannot run to a friend who has been harmed. One false step and you may beat them to the pearly gates. Some hesitate. Others look away, which is the easiest thing to do. They don’t want to see what may become of them one day.

Sgt. Rasmussen is unwavering in his attempt to show a complete lack of empathy. He has a cruel job. He also must maintain order. With prisoners that is best done by impressing upon them that they will be afforded no sympathy during their stay. If you want something you will have to work harder for it or go without. He’s not above lying to them, either. If that beach isn’t cleared of landmines no one is going anywhere. Not the Sergeant and certainly not any of the “disarmed enemy forces.”

Werner and Ernst (the twins) work harder with food in their stomachs. They help drag a cart full of mines through the sand to be counted in front of Sgt. Rasmussen. After the day’s work is done the boys sit around to relax. Some even build toys. The twins find a beetle in a nearby field and name it. My mind immediately recalls German war veteran and literary giant Ernst Jünger [2] for whom six species of beetles and a prize in entomology are actually named. Jünger said in his epic war memoir Storm of Steel that he was collecting beetles in the trenches during WWI.

For a moment we let our guard down. Then a scene reminds us of why they were there in the first place. The Sergeant wakes up to a noisy dawn. It seems that the Brits have been drinking all night and followed Lieutenant Ebbe down to the barracks. They’ve pulled all the boys out front to humiliate them. Rasmussen walks over to find Ludwig on his knees being abused in front of the others. They piss on him. Blue eyed Sebastian breaks ranks and tries to cover him with his own body. They put a gun to his head and begin to count in German. Finally Sgt. Rasmussen dismisses the British officers, saying he “needs all of these boys.” It’s another crack in the emotionless armor he’s walked around in since the beginning of the film. More importantly this scene is meant to show that denying their rights as prisoners of war was a group effort. We cannot simply blame the Danes. Ultimately it was Winston Churchill who finally approved the use of forced labor after the war. Most of the mine sweeping in Denmark was carried out under the supervision and instruction of the United Kingdom. The Soviets and Americans participated in the active suspension of POW rights as well. This is our people at their worst. A grim reminder that the Second World War was in fact, a civil war among whites. As an American I know the residual effects of your civilization defining itself by committing to a fratricidal war. If ever again a conflict of this sort befell our race it would end us. There is no justice in self-hatred and no redemption in collective suicide.

So the stage is set. Lt. Ebbe rages against the failure of Danish sovereignty during the war by showing nothing but contempt for the German prisoners. Sgt. Rasmussen wants a safe and sane nation and so rebels inward — treating any sentimental feelings as if they were live mines in need of immediate removal. The boys struggle for food and freedom to return to their Fatherland and as the twins put it: “rebuild the Reich.” Each and all are fighting what is the greatest enemy of white warriors everywhere, at any time: indignity. It is that fight that defines our geopolitics, trade deals, and space programs. It defines our post-war hostilities and the love of each unique European identity whether in conflict or harmony with the others. It’s why we tailor clothing and write symphonies. It’s why we invented plumbing. It’s the reason we build our churches. We struggle — individually and together — against indignity. We always have. This is the struggle that defines us as white people.

Remember that when you watch these people fight to survive such events. You will see brother lose brother and boys give into fear. You will see hard men grow soft, only to hate themselves for what little bit of humanity they let rise to the surface. This is a story of death and pain. Fraternity and fragility. Of men at war within themselves during a time of peace, and young boys on a losing side trying to find their way home. We all want our dignity. If we strip it away from another then we rob ourselves of it as well.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.