lundi, 30 mars 2020

"Antes de la historia: Algunas notas asistemáticas" (1975)

"Antes de la historia: Algunas notas asistemáticas" (1975)

Armin Mohler, Nouvelle École 27-28 (1975).

Del tipo de hombre que concede una importancia especial a la historia, queremos decir que es un ser que se siente incómodo en este presente y que busca volver en sus sueños a las épocas que ama y, por esta razón, podemos decir que es "conservador". Para describir esta actitud, que hoy en día comienza a parecer una epidemia, se ha acuñado el término "nostalgia". La nostalgia es un fenómeno con múltiples aspectos y, a la luz de estos, no resulta fácil emitir un juicio. Pero parece que no depende de unas actitudes intelectuales fundamentales. Hay conservadores nostálgicos y conservadores que no lo son, mientras que un sinnúmero de no conservadores experimentan una intensa nostalgia. De todas formas, la nostalgia no es un elemento constitutivo del conservadurismo; y el hecho de que uno sea o no nostálgico no es lícito concluir que alguien es o no es conservador.

- La historia está cerca

La mayoría de los malentendidos sobre el tema de la historia provienen del hecho de que la consideramos distante en el tiempo. Ciertamente la historia no es inmediatamente perceptible. Pero no por ello tiene menos importancia en el presente. Podríamos concebir nuestra relación con ella según el modelo de la holografía, que fue introducido en 1948 por Dennis Gabor. Se trata esencialmente de un nuevo tipo de "fotografía", capaz de representar tanto los contornos como el reverso de un objeto, aunque nuestro ojo sólo puede tomar su propia perspectiva. El hombre sin sentido histórico es como quien se ve en un espejo: se ve a sí mismo como si estuviera transcrito en una superficie, con las distorsiones y omisiones que esto conlleva. Tener sentido histórico significa no contentarse sólo con esta dimensión. Y, para seguir con la imagen que hemos tomado como ejemplo, estudiar la historia significa sostener un segundo espejo detrás de la cabeza, o todo un sistema de espejos, para verse desde todos los ángulos y así lograr una distancia con respecto a uno mismo.

- La historia no es una clase académica.

El beneficio que se obtiene de la historia es generalmente de orden moral. Alabamos los ejemplos que esperamos igualar. Afirmamos que nos ayuda a evitar los errores de los demás. Y así sucesivamente. Los historiadores no han escatimado esfuerzos en lo que se refiere a estos supuestos efectos directamente educativos de la historia. Los sucesores de los grandes hombres son generalmente pocos en número; y los errores se ensayan fatigosamente. Si la historia tiene un efecto educativo, éste se manifiesta de la forma menos directa, por decir algo.

- La historia permite una observación verificable

La historia tiene un poder disciplinario porque su función es la misma que la de la experimentación en el dominio de las ciencias naturales: la historia ofrece la única posibilidad de efectuar una observación verificable a nivel humano, tal como la experimentación la ofrece a nivel de la naturaleza. Esta observación es más fácil de hacer ya que la filosofía se ha degradado a un modesto papel de secretario en las reuniones interdisciplinares. La lógica tiene ciertamente sus inducciones, pero sólo en abstracto. Lo que tratamos de distinguir en el ámbito humano, como "naturaleza", "alma" (Seele) y "espíritu" (Geist), está tan íntimamente enredado que la lógica se esfuerza por comprenderlo. ¿Qué podría decir realmente verificable sobre una cosa, una persona, un evento humano? Podría decir qué es, en qué se convertirá con el tiempo y cómo cambia mientras tanto. Sobre los detalles puede haber diferencias de opinión: en términos generales, sin embargo, un consenso es posible.

- La verificabilidad no lo es todo

Quien comenta los severos límites de la observación verificable se expone generalmente a la sospecha de querer desvalorizar toda observación adelantada. Pero no tendría sentido actuar de esta manera: sería decir que cualquier intento de volver a las raíces, cualquier proyecto de gran envergadura debería ser limitado en consecuencia, y que la fuerza creativa en el hombre debería dejarse marchitar. En la esfera de la acción humana, la historia tiene una función particular: "verificabilidad" no significa otra cosa más. Y llamar a esa función "compensatoria" sería minimizarla: ya que la experiencia de la historia puede tener dos efectos contrarios y radicalmente opuestos.

- A través de la historia experimentamos lo complejo

Seguiría siendo una de esas simplificaciones inadmisibles, como en el caso de la cuestión de la nostalgia, decir que el "conservador" experimenta la historia como un absurdo. Algunos autores han utilizado la metáfora de "lo in-significativo" ("l'in-signifiant") para denotar aquello que aparece efectivamente en todo acontecimiento histórico: a saber, el hecho de la experiencia de que la historia representa siempre un exceso con respecto a los esquemas interpretativos que tratamos de atribuirle en el pensamiento. La experiencia fundamental según la cual "el mundo no es divisible", es decir, que el pensamiento humano y la realidad nunca pueden coincidir, alcanza en la dimensión histórica una intensificación que se podría comparar con un "efecto estéreo". La historia es una escuela de humildad: todos los intentos de explicación monocausal (o incluso bi- y tricausal) se hacen añicos contra ella, y nos hace conscientes del carácter complejo de toda realidad. Esto no tiene por qué molestarnos, ni siquiera desalentarnos, sino todo lo contrario: de una manera difícil de definir (e inexplicable en términos racionales), esto puede -de hecho- impulsarnos a una apreciación más profunda. Al darnos cuenta de lo complejo que es el mundo, vivimos una especie de segundo nacimiento.

- A través de la historia experimentamos la forma.

"Darle un significado a lo que no tiene significado" es igualmente una fórmula de la que debemos desconfiar. Desmiente una psicología un tanto escuálida. Es cierto que el mundo no tiene sentido y que, como el hombre no puede vivir sin sentido, pues bien, se construye uno. Pero la relación que debemos tener con la historia es aún más esencial. Este "segundo nacimiento" no sólo consiste en la experiencia de la complejidad del mundo, sino que también reside en nuestro impulso de contraponer a lo complejo (Benn o Montherlant dirían "contra el caos") una forma, una configuración. Lo que nos mueve profundamente en la historia es que el hombre siempre busca, precisamente a partir de esta experiencia de una realidad compleja, e incluso en las situaciones más desesperadas, dejar todavía un rastro detrás de él. Aunque sólo sea un rasguño en una realidad tan compacta, como dijo Malraux en alguna parte, con esa brillante despreocupación que hizo suya.

El hombre de la Aufklärung [Ilustración] dirá: "No es mucho". Nuestra respuesta sólo puede ser: "Pero lo es".

Tomado de : https://ferguscullen.blogspot.com/2020/01/armin-mohler-be...

00:38 Publié dans Nouvelle Droite, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : armin mohler, nouvelle droite, neue rechte, nouvelle droite allemande, révolution conservatrice, histoire, philosophie de l'histoire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Dante et saint Augustin, millénarisme et théorie politique

Dante et saint Augustin, millénarisme et théorie politique

par Sylvain Métafiot

Ex: http://www.mapausecafe.net

Article initialement paru sur Philitt

Poète mais également homme politique et penseur chrétien, Dante Alighieri développe l’idée que la monarchie terrestre peut restaurer la pureté humaine d’avant la Chute. Il dégage le pouvoir de l’intellect humain, désormais libre, substituant en cela la notion d’humanité à celle de chrétienté. Une vision qui fait suite aux réflexions d’Augustin d’Hippone sur la dualité entre Empire et Royaume divin dans l’Empire romain chrétien, un millénaire plus tôt.

En 1295, en pleine opposition florentine entre guelfes (partisans du Pape) et gibelins (partisans de l’Empereur), Dante Alighieri fait son entrée dans la vie publique. Proche des guelfes blancs (famille Vieri de’Cerchi) il est exilé et condamné à mort par le clan des guelfes noirs (famille Donati) en 1302. Le 31 mars 1311 l’auteur de La Divine Comédie écrit une lettre (5e Épître) à tous les princes d’Italie pour annoncer le triomphe d’Henri VII venu, selon lui, libérer les Italiens de l’esclavage dans lequel ils se trouvent. Dans cette invective contre la résistance de la commune de Florence, Dante stigmatise la rébellion des partisans du pape contre l’empereur. Or, dans d’autres textes, le poète dénonce l’état de corruption dans lequel se trouvent certaines terres de l’Empire, dont l’Italie.

Dans le chant XVI du Purgatoire, Dante et Virgile cherchent leur chemin à travers l’épaisse fumée du cercle des ombres abandonnées à la colère. Ils rencontrent Marc Lombard qui, à travers ses paroles, leur sert de guide. Il leur parle des causes de la corruption contemporaine, expliquant l’origine de l’âme et exposant l’opposition entre le passé et la coexistence des deux soleils (l’empereur et le pape).

La Cité de Dieu de Saint Augustin

Selon Augustin, « deux amours ont fait deux cités : l’amour de soi poussé jusqu’au mépris de Dieu, la cité terrestre ; l’amour de Dieu poussé jusqu’au mépris de soi, la cité céleste ». Ces deux cités mystiques (ou idéelles) coexistent dans chaque être humain. La cité terrestre étant une forme de défiguration de la cité de Dieu. Celle-ci n’est cependant pas l’Église terrestre, de même que la cité terrestre ne se confond pas avec l’Empire ou l’État, malgré d’évidentes similitudes (leur objectif est la paix : l’harmonie et l’ordre pour la cité céleste, la domination pour la cité terrestre). Il y a une hiérarchie dans la cité céleste : l’asservissement des choses matérielles de la cité terrestre, le désordre intérieur de chacun fait entrer en compétition et en guerre avec les autres pour imposer un ordre arbitraire. Le peuple est « une multitude d’être raisonnables associés par la participation dans la concorde aux biens qu’ils aiment ». Dans la cité terrestre la justice est masquée par la poursuite des biens matériels. Il faut respecter les lois pour qu’une paix, relative et imparfaite, soit maintenue.

Notons que, selon l’historien de la pensée politique Michel Senellart, chez Saint Augustin le péché ne provient pas de la chair mais de la volonté d’Adam : la corruption de la chair est la conséquence du péché originel. La volonté humaine est impuissante et tombée dans la servitude. Selon Senellart « L’État en tant qu’organe de répression a donc son rôle à jouer dans la discipline apostolique ». Toutefois, si l’homme se trouve incapable d’instaurer un ordre harmonieux, dans la paix et la concorde, l’idée de sociabilité n’est pas absente de la pensée d’Augustin. L’homme doit bénéficier de la grâce divine pour éloigner l’ignorance et le péché.

Si l’Église et l’État sont deux structures imparfaites, quel est leur rôle dans le Salut ? « Quelle place accorder au Prince, à l’Empereur ? » se demande Augustin. Les souverains temporels, comme les souverains pontificaux, pourraient avoir le droit de gouverner leurs sujets respectifs. L’État peut aider à corriger la volonté humaine, mais il n’est pas bon en lui-même et est victime des hommes. L’Empire joue un rôle providentiel en favorisant l’expansion de l’Église. Mais la providence divine est inconnue aux hommes. Tout ce qui est terrestre n’est que provisoire. Augustin ôte ainsi toute signification eschatologique à l’Empire. Il ouvre la perspective d’une expansion de l’église hors du temps et de l’espace romain (même s’il ne souhaite pas la fin de Rome).

La doctrine des « deux glaives » et les « dualistes »

Le XIIe siècle voit l’apparition de thèses hiérocratiques (système de gouvernement représenté par une caste religieuse), notamment la théorie des deux glaives de Bernard de Clairvaux (1090-1153). Ce dernier réinterprète certains passages des écritures, comme celui de l’Évangile selon saint Luc dans lequel les apôtres voulant défendre Jésus lui disent : « Maître, il y a ici deux glaives » et Jésus de répondre « cela suffit ». La notion de glaive prend ici un sens punitif : le glaive de la parole divine peut traduire la colère de Dieu ; tandis que le glaive royal punirait les méchants et récompenserais les bons. Les deux pouvoirs se distinguent autant qu’ils concordent entre eux. Dans l’Église, des voix s’étaient élevées affirmant que les princes tenaient leurs glaives des prêtres, d’où une soumission du pouvoir temporel au pouvoir spirituel. Saint Bernard affirme que les deux glaives reviennent à l’Église, le pape étant le vicaire du Christ. Puisque les deux pouvoirs poursuivent le même but (le salut), il est nécessaire que le vicaire du Christ possède le pouvoir suprême. On ne peut utiliser le glaive matériel sans l’assentiment du Pape et celui-ci peut utiliser son pouvoir sur toute action coercitive.

Pour les décrétalistes (jurisconsultes experts dans la connaissance des règles ecclésiastiques), c’est la souveraineté du pape qui assure l’empereur de la plénitude de son pouvoir. Les canonistes expriment tout de même une grande prudence dans la suprématie pontificale. Ils établissent une voie moyenne entre juristes purs qui autonomisent le politique et un gouvernement hiérocratique de la chrétienté mettant le pouvoir temporel sous soumission totale du Pape. Le juriste Étienne de Tournai (1128-1203) affirme ainsi que « dans le même acte, sous le même roi, existe deux peuples, et selon eux deux genres de vie, et selon eux deux principes, et selon eux un double ordre de juridiction […] le droit divin et le droit humain rend à chacun ce qui lui appartient et toutes choses seront à leur place ». De son côté, le légiste Huguccio de Pise (1140-1210) attaque la théorie des deux glaives : « Il y a eu un empereur avant qu’il y ait eu un pape, et un empire avant qu’existe une papauté. Et c’est pour signifier que les deux puissances doivent êtres divisées et séparées qu’il fut dit : il y a ici deux glaives ». Au siècle suivant les décrétalistes se rallieront aux formulations de saint Bernard : une dualité de fonction au sein d’un seul corps, l’Église.

La Monarchie universelle de Dante

Revenons au poète florentin. Dans La Monarchie universelle (1313), Dante cherche à démontrer la légitimité du caractère romain de l’Empire. Dans le premier livre, il montre que la nécessité de cette monarchie provient de la raison et de la providence. Du point de vue de la raison, la monarchie universelle se déduit de la nécessité d’une paix universelle. Dante cherche ensuite à définir le propre de l’intellect humain. La pensée et l’action étant les actions matérielles de l’homme, la paix universelle est le seul moyen pour arriver à la destination naturelle de l’homme. S’inspirant d’Aristote il affirme que lorsque plusieurs choses ont une même fin il est nécessaire qu’une chose règle et gouverne les autres. Détenteur en lui-même d’une nature corruptible et incorruptible l’homme possède deux finalités : il tend à la fois vers une béatitude terrestre et une béatitude céleste. De fait, Dante élabore deux voies (à la façon des deux soleils dans le chant XVI du Purgatoire vu plus haut) :

- La voie corruptible, fondée sur l’ordre de la nature, la béatitude terrestre, les enseignements des philosophes (l’empereur conduit les hommes au bonheur grâce à la philosophie), les vertus naturelles, etc.

- La voie incorruptible, basée sur l’ordre de la grâce, la béatitude céleste, l’enseignement spirituel, les vertus théologiques, la révélation de l’esprit saint à travers laquelle le pape conduit au bonheur.

Il convient toutefois de ne pas exagérer le dualisme de Dante. Proche des canonistes du XIIe siècle, il cherche à penser une autonomie pleine et entière de la monarchie universelle à l’égard de la papauté. Mais la monarchie ne s’identifie pas avec l’empire qui, lui, est en complète déliquescence. Dante veut refonder un ordre universel en accord avec la justice divine. Cette dualité est pensée selon un équilibre harmonique : il ne peut y avoir de conflit entre la foi et la raison, car les deux autorités, venant de Dieu, n’ont qu’à se développer selon leurs natures respectives pour s’accorder.

Enfin, dans la 6e Épître, Dante reprend les thèses fondamentales de la Monarchie. Il utilise cette doctrine comme un argument dans la critique de la notion de liberté : Florence, en affirmant son indépendance vis-à-vis de l’Empire et sa liberté à se gouverner elle-même (en choisissant ses magistrats), rejette la vraie liberté, considérée comme un héritage sacré garantie par une longue habitude. Dante attribue aux Florentins la volonté de considérer le pouvoir impérial comme caduque. Il concède pourtant que l’autorité impériale a négligée l’Italie. C’est pourquoi il assimile cette revendication de liberté à une affirmation absurde. Il prétend discerner dans la réalité des temps les signes divins de la providence. Il donne ainsi les instruments théoriques d’une déconstruction de la réalité florentine : la liberté comme privation de la sagesse. La plus haute réflexion politique de Dante s’achève ainsi sur un trône vide dans le chant 30 du Paradis de la Divine Comédie.

Enfin, dans la 6e Épître, Dante reprend les thèses fondamentales de la Monarchie. Il utilise cette doctrine comme un argument dans la critique de la notion de liberté : Florence, en affirmant son indépendance vis-à-vis de l’Empire et sa liberté à se gouverner elle-même (en choisissant ses magistrats), rejette la vraie liberté, considérée comme un héritage sacré garantie par une longue habitude. Dante attribue aux Florentins la volonté de considérer le pouvoir impérial comme caduque. Il concède pourtant que l’autorité impériale a négligée l’Italie. C’est pourquoi il assimile cette revendication de liberté à une affirmation absurde. Il prétend discerner dans la réalité des temps les signes divins de la providence. Il donne ainsi les instruments théoriques d’une déconstruction de la réalité florentine : la liberté comme privation de la sagesse. La plus haute réflexion politique de Dante s’achève ainsi sur un trône vide dans le chant 30 du Paradis de la Divine Comédie.

Sylvain Métafiot

00:32 Publié dans Philosophie, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : dante, saint augustin, théologie politique, philosophie, philosophie politique, théorie politique, théologie, politologie, sciences politiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Voir au-delà de l’épidémie. Lettre aux lecteurs et amis de l’Antipresse

Voir au-delà de l’épidémie.

Lettre aux lecteurs et amis de l’Antipresse

par Slobodan Despot

Ramenons les choses à leur juste mesure. Un tremblement de terre d’où vous êtes sorti indemne restera moins profondément gravé dans votre souvenir qu’une mauvaise chute dans l’escalier qui vous a estropié. Nous pouvons nous faire contaminer par la fièvre collective en lisant les nouvelles de l’épidémie, c’est en définitive notre destin personnel, et celui de notre famille et de nos proches, qui nous préoccupe vraiment.

Cette épidémie, au jour où je parle, aurait contaminé un demi-million de personnes et fait 26’000 morts dans le monde, dont 200 en Suisse. Dans ce même pays, en 2017, une vague de grippe a causé, les six premières semaines de l’année, près de 1500 décès supplémentaires chez les personnes de plus de 65 ans par rapport aux chiffres normalement attendus à cette époque de l’année. Je cite des chiffres du gouvernement.

Ce n’est pas pour minimiser ce qui nous arrive, c’est pour le replacer dans un cadre rationnel et ne pas céder à l’envie de malheur. De toute façon, je l’ai dit, tout ce qui nous frappe dans notre propre vie et notre sécurité a la dimension d’un cataclysme, qu’il s’agisse d’une pandémie ou d’un drame familial. Des gens qui me sont proches ont été contaminés. Certains luttent avec leurs dernières énergies pour s’en sortir, pour d’autres c’est une grosse grippe.

Mais tout le monde est accroché aux nouvelles, alarmantes, approximatives, contradictoires. On essaie de deviner son propre sort dans des statistiques. Autant le chercher dans le marc de café.

Protégeons-nous comme il se doit, ne laissons aucune précaution de côté mais n’oublions pas que la meilleure armure n’a jamais empêché personne de mourir au combat. C’est la loi de la lutte et c’est la loi de la vie. Cette société s’effondre sous nos yeux pour avoir voulu l’oublier.

Ancrons-nous donc dans notre fragilité et essayons de garder les yeux grands ouverts. Nous sortirons de cette épidémie tôt ou tard. Si la mortalité du virus ne grimpe pas en flèche, l’immobilisation forcée des sociétés devra être levée avant la fin de l’alerte, parce que les dégâts du confinement, économiques, psychologiques, humains, dépasseront les risques de la contagion. Il va bien falloir sortir à l’air libre.

A ce moment-là, sans doute, nous remettrons en marche notre cerveau. Nous essaierons de comprendre ce qui s’est produit. Nous verrons un millier de choses qui dans la panique actuelle nous échappent — même des choses positives. Nous demanderons des comptes.

Car pendant que nous guettons les chiffres et attendons les thérapies miracles, les affaires continuent, et bien plus fort qu’avant. Sous couvert d’état d’urgence, on adopte des mesures qui ne seront pas levées avec le confinement. Au contraire: qui vont définir le monde où nous vivrons demain.

En France et ailleurs, on adapte les lois sur le travail à la situation de crise… sans aucune intention de revenir en arrière. En Allemagne, on a fermé les frontières pour tout le monde, sauf pour les migrants. Pourquoi? Sont-ils moins contagieux? En Suisse, en Autriche, partout, on vous propose de troquer votre liberté contre de l’hygiène, on trouve formidable de recopier le système de contrôle social chinois, absolu et totalitaire, fait pour une civilisation qui n’a rien à voir avec la nôtre, qui ignore l’autonomie de l’individu. En Orient, le divorce entre les États-Unis et la Chine est devenu agressif et irréversible. En Europe, ces mêmes États-Unis profitent de manœuvres militaires qu’ils n’ont pas annulées à cause du virus pour renucléariser l’Europe avec des armes tactiques tournées vers la Russie. En Russie, justement, on officialise l’autocratie. Partout, c’est déjà très visible, le citoyen est en train de se faire déposséder de ses droits et de ses avoirs au profit de l’État tout puissant ou des multinationales. Ou plutôt, d’une alliance des deux.

A l’issue de cette crise, des millions de gens vont se trouver dans la rue, des entreprises seront par terre et d’autres, comme Amazon, auront prospéré comme jamais de leur vie. Pourquoi la pandémie ne serait-elle une opportunité que pour les puissants et pas pour nous, pas pour les gens ordinaires?

Si nous devons saisir cette opportunité, ou au moins défendre ce qui est à nous, ce n’est pas après la crise que nous pouvons le faire. C’est maintenant, tout de suite. C’est le moment de nous demander comment nous avons pu nous laisser gouverner par des gens d’une telle incompétence, d’une telle lâcheté, d’une telle indécision. C’est le moment de nous demander comment il se fait que les systèmes de santé les plus sophistiqués, les plus coûteux au monde se soient effondrés en quelques jours devant cette épidémie, alors que des pays bien moins riches ont pu réagir et au moins se procurer les moyens de base, pourquoi les courbes de contagion grimpent en flèche dans les pays les plus développés et les plus aseptisés. C’est le moment de comprendre pourquoi la malheureuse Italie a été secourue par la Chine, Cuba et la Russie alors que ses voisins de l’UE n’auront pas bougé le petit doigt. C’est le moment de s’interroger pourquoi les neuf dixièmes des morts du virus dans le monde se situent dans l’Occident ultralibéral. C’est le moment d’admettre que les sociétés contaminées par l’ultralibéralisme n’en réchapperont pas.

A l’issue de cette crise, l’Union européenne n’existera plus sinon comme une survivance administrative d’un autre temps, à la fois oppressante et superflue. L’État de droit ne sera plus que du passé. C’est maintenant qu’il nous faut réfléchir comment nous allons protéger nos libertés et nos biens dans ce monde-là, non une fois qu’on nous aura dépouillés de tout.

Nous devons aujourd’hui, tout à la fois, nous ancrer dans le présent et nous projeter dans l’avenir, de toutes nos forces. Nous devons penser comme des auteurs de science-fiction. Les romanciers auront vu plus juste que tous les administrateurs et tous les analystes. Nous comprendrons très vite qu’il faut investir non seulement notre cerveau, mais encore notre cœur, notre âme et toute notre vie dans la compréhension de ce qui nous arrive. Parce que le prix de la survie, demain, risque d’être plus coûteux que la vie elle-même.

Vous voulez rester des individus libres, des citoyens, plutôt que de devenir une masse obéissante et manipulée? Nous aussi. Sortons de cette hypnose! Lisons ensemble, réfléchissons ensemble, restons critiques et mal élevés. Les masques qu’on nous fait porter ne doivent pas devenir des bâillons! Le grand poète Pouchkine, mis en quarantaine pendant trois mois à cause du choléra (qui était autrement plus meurtrier), n’a pas passé ses journées à feuilleter la chronique des décès ni à attendre le traitement qui sauve. Il en a profité pour produire des dizaines d’œuvres. Ce fut la période la plus fertile de sa courte vie. Et c’est le meilleur moyen de faire du miel avec la sueur de l’angoisse et de l’amertume.

L’Antipresse a été créée à cause de la crise des médias et pour les temps de crise. Ce n’est pas maintenant que nous allons bêler comme des moutons. A l’heure même où le système médiatique fondé sur la publicité s’effondre, la soif d’information et d’explication du public n’a jamais été aussi grande — et la confiance dans les médias transformés en porte-parole du pouvoir ne survivra pas à la peur qu’ils diffusent.

Nous invitons tous nos lecteurs à diffuser nos textes et nos dossiers, à faire connaître notre travail autour d’eux, à poster chaque article qui les a frappés sur les réseaux sociaux et à lever leur fronde contre tous les écrans de Big Brother. Nous sommes là pour leur servir les cailloux!

PS — Les meilleurs moyens de nous soutenir dans notre développement:

1) vous abonner;

2) prendre un abonnement de soutien;

3) faire un don;

4) …et avant toutes choses, nous faire découvrir en envoyant la présente lettre à tous vos amis!

00:16 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, covid-19, pandémie, coronavirus, épidémie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

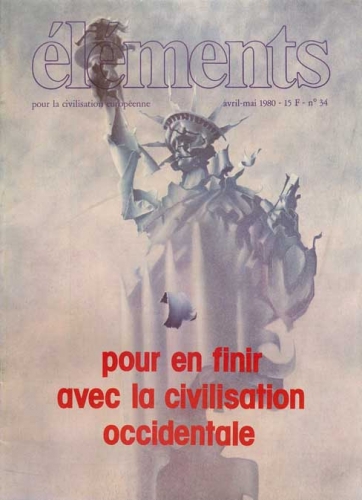

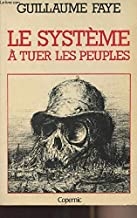

Guillaume Faye: “Finishing with Western Civilisation” (1980)

Guillaume Faye:

“Finishing with Western Civilisation” (1980)

My translation of Faye’s “Pour en finir avec la civilisation occidentale,” Éléments 34 (1980). This text distinguishes and advocates Europe (or Hesperia) over-against “the Western system.” The nouvelle droite-period Faye (before 1987), whom we see at work here, is quite different from the post-hiatus Faye (1998–2019) known to the Anglophone world. Note the apparently positive assessment of political Islam (p. 5) and the opposition to the identitarianism with which he came to be associated (pp. 6–7).

French original:

http://www.archiveseroe.eu/occident-a49054848

PDF of this translation:

https://www.academia.edu/42174979/Guillaume_Faye_Finishin...

Related texts on rival strains in European thought and deed:

https://ferguscullen.blogspot.com/2020/01/the-clash-of-wo... (Faye)

https://ferguscullen.blogspot.com/2020/01/giorgio-locchi-... (Giorgio Locchi)

“This Europe, always on the point of cutting its own throat in its unholy blindness,” wrote Martin Heidegger in his Introduction to Metaphysics,

[l]ies today in the great pincers between Russia on the one side and America on the other. Russia and America, seen metaphysically, are both the same: the same hopeless frenzy of unchained technology and of the rootless organisation of the average man. When the farthest corner of the globe has been conquered technologically and can be exploited economically […] and time as history has vanished from all Dasein of all peoples […] there still looms like a spectre over all this uproar the question: for what?—to where?—then what?*

[* Translator’s note. Transl. Gregory Fried and Richard Polt (Yale, 2000), with some pedantic syntactical amendments by me. Faye’s French rendition differs a little: “‘Cette Europe qui, dans un incalculable aveuglement, se trouve toujours sur le point de se poignarder elle-même,’ écrit Martin Heidegger dans son Introduction à la métaphysique, ‘est prise aujourd’hui dans un étau entre la Russie d'une part et l’Amérique de l’autre. La Russie et l’Amérique sont, toutes deux, au point de vue métaphysique la même chose: la même frénésie de l’organisation sans racine de l’homme normalisé. Lorsque le dernier petit coin du globe terrestre est devenu exploitable économiquement […] et que le temps comme provenance a disparu de l’être-là de tous les peuples, alors la question: “Pour quel but? Où allons nous? et quoi ensuite?” est toujours présente et, à la façon d’un spectre, traverse toute cette sorcellerie.’”]

[* Translator’s note. Transl. Gregory Fried and Richard Polt (Yale, 2000), with some pedantic syntactical amendments by me. Faye’s French rendition differs a little: “‘Cette Europe qui, dans un incalculable aveuglement, se trouve toujours sur le point de se poignarder elle-même,’ écrit Martin Heidegger dans son Introduction à la métaphysique, ‘est prise aujourd’hui dans un étau entre la Russie d'une part et l’Amérique de l’autre. La Russie et l’Amérique sont, toutes deux, au point de vue métaphysique la même chose: la même frénésie de l’organisation sans racine de l’homme normalisé. Lorsque le dernier petit coin du globe terrestre est devenu exploitable économiquement […] et que le temps comme provenance a disparu de l’être-là de tous les peuples, alors la question: “Pour quel but? Où allons nous? et quoi ensuite?” est toujours présente et, à la façon d’un spectre, traverse toute cette sorcellerie.’”]

In the French countryside, we no longer dance the jig or sardana on festival days. The juke-box and pinball machine have colonised the last refuges of folk culture. In a German college, a boy of eighteen dies at last of an overdose, curled up in a toilet-cubicle. In the suburbs of Lille, thirty Malians live packed into a cellar. In Bangkok or Honolulu you can get yourself a girl of fifteen for five dollars. “It’s not prostitution, because everyone here does is,” states an American tourist brochure. In the suburbs of Mexico, an American firm manufacturing skateboards lays off a hundred workers. Houston reckons it’s more cost-effective to set up shop in Bogotá…

Such is the hideous face of the civilisation that, with an implacable logic, imposes itself on every continent, razing cultures under one planetary way of life and digesting the socio-political contests of the peoples which it has submitted to the same standard habits (habitudes de mœurs).* Indeed, why shout “U.S. go home!” if one wears jeans? For Konrad Lorenz, this civilisation discovered something worse than servitude or oppression: it invented “physiological domestication.” And more efficiently than Soviet Marxism, it realises a social experience of the end of history, with the objective of assuring the ubiquitous triumph of the bourgeois type, by way of a homogenising dynamic and a process of cultural involution.

[* Translator’s note. Faye: “les mêmes habitudes de mœurs (standard habits).”]

We must call this civilisation, in which the peoples of Asia, Africa, Europe and Latin America are stuck today, by its name: it is Western civilisation. Western civilisation is not European civilisation. It’s the monstrous progeny of European culture—which imprinted it with its dynamism and spirit of enterprise, but to which it’s fundamentally opposed—and of egalitarian ideologies derived from Judeo-Christian monotheism. It arose in America, which, in the aftermath of the Second World War, gave it its decisive impulse. The monotheist component of Western civilisation, identical in substance to that of Soviet society, is indeed clearly noticeable in its project: to impose a universal civilisation founded on the domination of the economy as class-of-life (classe-de-vie) and to depoliticise peoples to the profit of global “management.”

It’s therefore worth distinguishing Western civilisation from the Western system, which denotes the power that drives the expansion of the former. The Western system cannot, besides, be described in terms of a homogeneous power, constituted as such. It organises itself through a global network of micro-decisions, coherent but inorganic, which renders it relatively ungraspable and, to that extent, the more formidable. It encompasses the OECD business community, the managements of a hundred transnational corporations, a large percentage of the political personnel of “Western” nations, ruling circles of conservative “elites” in poor countries, part of the executives of international institutions, and most of the highest functionaries of banking institutions in the “developed” world. The Western system has its epicentre in the United States. It isn’t essentially political or statal, but proceeds by the mobilisation of the economy. Disregarding states, borders, religions, its “theory of praxis” rests less on the diffusion of an ideological corpus, or on constraint, than on the radical modification of cultural formations, oriented towards the American model.

But whoever thinks of the “West” thinks immediately of the “Third World.” It’s said that Alfred Sauvy coined this term a little after the conference of non-aligned nations at Bandung in 1955. But does the Third World exist? As a matter of fact, Soviet Leninism conceived the concept well before the term existed. In Imperialism, the Last Stage of Capitalism (1916), Lenin founds the doctrine that now inspires, more than ever, the foreign policy of the Soviet Union: to utilise poor countries as a mass to move against global capitalism, to make them objects of history and of revolution. Identical in this respect to Western liberalism, the Leninist ideology subordinates the independence of peoples to its universalist project. Leninism, which is an Occidentalism at its root, doesn’t envision national difference, and doesn’t conceive the nationalism of non-European peoples other than as a provisional instrument in the service of the same project as that of Occidentalism: one global homogeneous civilisation founded on economy. Besides, Karl Marx himself announces this kinship of Leninism and Western liberalism. In the British Rule in India and The Future Results of British Rule in India (1853), he was pleased to note that “British domination has completely demolished the strictures of Indian society,” and that “this part of the world, until then remaining inferior, is now annexed to the Western world.” For there is no greater obstacle to “socialism” than traditional societies. Did Georges Marchais not say that it was to abolish the droit du seigneur that the Soviet army invaded Afghanistan?

Does the Third World, then, encompass those peoples that, renouncing their own cultural identity, become candidates for Westernisation, as proletarians for bourgeoisification? Where necessary nurturing a resentment against their model? The strength of the Western system, objectively complicit in this regard with the Leninist project, is in understanding that the desire to assimilate always prevails over resentment: the Third World doesn’t threaten it. For the Venezuelan Carlos Rangel, “the essence of Third-Worldism is neither poverty nor underdevelopment,” but “a discontentment that impedes neither a Western way of live nor an ostentatious wealth” (“Pourquoi l’Occident est en train de perdre le Tiers-Monde,” Politique internationale, Spring 1979). For Rangel, “peoples belong to the Third World who, though very dissimilar, share the same deep sense of alienation from and antagonism towards successful non-communist countries, and who find themselves in relation to the latter in a position analogous to that of populations of colour in a society where power is in the hands of whites.” These peoples, Rangel continues, don’t feel themselves “founding members of the club called Western civilisation.” Even Japan or Spain, and France at a pinch, “will never be as integrated into Western capitalist society as New Zealand, which shares culturally in the source from which capitalism takes its impulse”—to wit, “the Anglo-Saxon hegemony installed by England and which the United States have taken up.” Rangel adds: “The slightest lack of identification with the primary source of ideas, and with the current seat of power, is an unavoidable cause of national anxiety and dissatisfaction.”

Membership of the third world, or of Western civilisation, thus remains a cultural fact. It’s the whole planet that’s experiencing an identity crisis. Like equality always proclaimed and never achieved, the Western model contains a logic of alienation. Western civilisation presents itself explicitly as a purely economic ensemble whose primary condition of membership is quality of life (niveau de vie); but implicitly, this civilisation structures itself hierarchically in two cultural levels: the “club” members and the “others,” who can never be better than half-Western, and who can never join the “club.” Why? Because they don’t belong to the Anglo-American world, which thinks itself the epicentre of the West. Also, Western civilisation, because of its dominant Anglo-American element, itself rejects any identification with European culture, particularly in light of the Latin, Germanic, Celtic or Slavic components of the latter. But this dichotomy might be pushed even further: to the degree that Western civilisation fully expresses the American project, and that America constitutes itself on a rejection of Europe, the essence of Western civilisation is the rupture with European culture, which it attacks even by dissolving it through cultural ethnocide and political neutralisation.

Western neo-colonialism—such as manifests itself in all parts of the world, from Ireland to Indonesia—is grounded essentially in American liberal ideology, which has imposed itself on international organisations. We would never finish citing those peoples whose own forms of sovereignty have been destroyed to the benefit of a “democracy” designed to integrate these peoples into the Western and mercantile economic order. Neo-colonialism instituted the direst of dependencies and obliterated the chief among liberties, which consists, for a people, in governing itself according to its own world-conception. And it’s the local bourgeoisie, created by the West, that becomes the instrument of that politico-cultural dispossession.*

[* Author’s note. Cf. the studies carried out by the Africanologist Hubert Deschamp on the destruction of cultural forms of African sovereignty by “democracy,” notably the systems of balanced anarchy and of chiefdom proper to certain American peoples.]

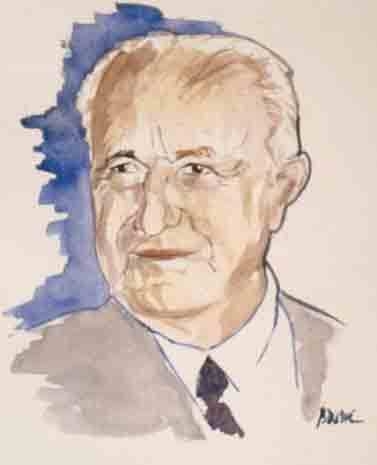

François Perroux

It’s the very idea of Third-World economic development that we ought, in fact, to suspect. This notion presupposes in effect that the peoples of the Third World ought necessarily to follow the path of Western industrialisation. Now this accords singularly well with the liberal desire for international division of labour and economic specialisation of zones, indispensable for the modern capitalism of planetary free exchange. And who, under doctrinal and humanitarian camouflage (the “right to development”) thus advocates Third-World industrialisation? Those who defend the interests of an economic system in which the growth of global industrial commerce is as necessary as warm water for mackerel shoals.* Again and again, François Perroux has shown that the “overall quality of life” in “developing” countries that are considered already nearly developed, was lower than that achieved by traditional societies. Inversely, poorer countries, or less industrialised zones, know a real “quality of life” superior to what OECD figures might have one believe.** And until today, the United States have been the only real beneficiaries of the industrialisation of Asia, Africa and South America.

It’s the very idea of Third-World economic development that we ought, in fact, to suspect. This notion presupposes in effect that the peoples of the Third World ought necessarily to follow the path of Western industrialisation. Now this accords singularly well with the liberal desire for international division of labour and economic specialisation of zones, indispensable for the modern capitalism of planetary free exchange. And who, under doctrinal and humanitarian camouflage (the “right to development”) thus advocates Third-World industrialisation? Those who defend the interests of an economic system in which the growth of global industrial commerce is as necessary as warm water for mackerel shoals.* Again and again, François Perroux has shown that the “overall quality of life” in “developing” countries that are considered already nearly developed, was lower than that achieved by traditional societies. Inversely, poorer countries, or less industrialised zones, know a real “quality of life” superior to what OECD figures might have one believe.** And until today, the United States have been the only real beneficiaries of the industrialisation of Asia, Africa and South America.

[* Author’s note. It’s interesting to note that despite the theoretical positions of Marxist economists, socialist countries have practiced upon the Third World the same economic mercantilism as capitalist countries. The exterior economic practice of socialism is capitalist and mercantile.]

[** Author’s note. Cf. Daniel Joussen, “La faim n’est qu’une consequence,” Le Monde (29 December 1979).]

But we mustn’t delude ourselves: the industrialisation of the planet is irreversible. The share of consumption of Asia or Latin America never ceases to grow. On the other hand, it’s the form of this industrialisation, free-exchangist and subject to the Western development model, which must be critiqued. Inasmuch as industrial structures resemble one another, modes of consumption are standardised and Americanised. Besides, if this form of industrialisation is a factor of “development” for certain countries, it’s the source of serious instability and under-development for many others: “Four fifths of industrial exports of new countries,” writes Jean Lemperière, “are provided by nine countries: the workshops of the Far East, India, the three greater Latin American countries, and Israel” (Le Monde, 22 January 1980).

In the end, a globalised industrial economy will turn out to be of an extreme fragility in the face of crisis, given the network of dependencies which it weaves between nations. On the other hand, “ethno-national” ideologies might very well help certain peoples free themselves from Western neo-colonialism. These ideologies appeared in Europe from the beginning of the fourteenth century and already opposed a considerable universalism—that of ecclesiastical power.* They appealed to the constitution of a secular state coextensive with the nation, and referred themselves to the galvanising myth of ancient Roman imperium. Reprised by Fichte and Herder in the eighteenth century, ethno-national ideas aspire to radically challenge universalist and individualist ideologies, and themselves played an important role in movements of national liberation in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

[* Author’s note. Around 1300, Pierre Dubon, jurist of Philippe le Bel, urges the abolition of papal and ecclesiastical power. In the fourteenth century, in France and Italy, intellectuals envisages the nation-state as the political structure of European peoples, and extolled the idea of national power. These themes were reprised by Petrarch and Machiavelli, who were also inspired by Marsilius of Padova, theoretician, from 1342, of the autonomous, secular state, and of the replacement with political nationalism of the theocratic idea.]

It’s also thanks to nationalist ideology that the peoples of Africa, Asia and America might mobilise against colonialism. Today, it’s still ethno-nationalism that, alone, might break the yoke of Western (or Soviet) neo-colonialism. “There is an adaptation,” writes Marcel Rouvier, “of the European ethno-national ideological model, because it corresponds to the exigencies of the situation of the Third-World in the twentieth century”; and the success of this ideology is foreseeable “with the decline of Marxist universalism, which had remained its sole serious competitor.” For Rouvier, the major theme of ethno-national combat is “the development of ideas in the essential quest for identity as the primary motor of history, for the permanence of a foundation which is the transmutation of the romanticist Volksgeist, for the deep legitimacy of a healthy nationalitarianism (nationalitarisme).”

In Mexico, a country carved up by the United States, we thus witness the construction, by the state and by the people, of an original nationalism, founded on the regeneration of an historic conscience which finds its specific foundations in Indian cultures. A new people thus create themselves, freed from “Western” history, and rethinking their destiny beginning with the recreation of their past. A beautiful lesson for us Europeans, who, beyond that “Western Christendom” in which we can no longer recognise ourselves, must also rethink our destiny by rediscovering the specific foundations of our culture in constructing an Indo-European myth.

In Africa, the adaptation of ethno-national ideology has also emerged, but under a less political and historical form than tribal and communitarian: “The value of African culture doesn’t concern certain phantasms or complexes repressed before Greek canons of beauty,” says—not without malice—the Senegalese cineaste Sembène Ousmane (Jeune Afrique, 19 September 1979). The search for authenticity, the choice of surnames and the return to traditional patriarchal customs, fought by Christianity and the United Nations, can make only idiots and scoundrels smile.

As for Islamic nationalism, it constitutes the happiest blow yet dealt to the civilising utopia of the American model. It calls into question the Western idea of mercantile growth and the primacy of economic development, while rejecting Marxism, rightly judged to be a factor of deculturation and, accessorily, as the instrument of Soviet neo-colonialism.

It’s also thanks to a surge in national conscience that China can attenuate the massifying effect of Marxism, and can thus effect a likely positive synthesis between ideas coming from the West and the pursuit of her destiny as people-continent (people-continent). She knew to adapt her ancestral cultural structures of sovereignty, and to constitute, “trusting in her own strength,” an historic power as independent of the Western mélange as from the Soviet bloc. It isn’t without good reason that China feels the need to no longer take on the role of historical actor alone, faced with two great universalisms, the American West and Russian “Sovietism.” In this game of three players, she can only ally itself to her opponent—the Soviet Union today, the United States tomorrow—she needs an partner-actor to join her. This is why it appeals to Europe, inciting the latter to shake off her lethargy, to re-enter history, to reconquer her liberty.

As China frees herself from “Sovietism,” so Europe must free herself from the West and reappropriate for herself the ethno-national ideologies she generated. To free oneself from Western civilisation is to begin by doubting the idea of Western solidarity imposed on Africa as upon Europe or Japan. For one must clearly distinguish, in geopolitics, between factual solidarities (solidarités factuelles) and real solidarities (solidarités réelles)—that’s to say, solidarities at once desirable and in conformity with historical interests and the people in question. The West and the Soviet bloc consist of ensembles of merely factual solidarity. Poland or Federal Germany, like Chile or Afghanistan, are not enmeshed in ensembles of real solidarity. Now the “Third-Worldist” left and “Occidentalist” right enforce, with concepts generated by their ideological vocabularies, the global status quo of blocs of factual solidarity. A new geopolitics begins with new definitions. The West and the Third World must disappear as geopolitical concepts. Let us speak of Europe, the United States, Latin America, the Soviet Union, or India. We must rethink the world in terms of organic ensembles of real solidarity: continental communities of destiny, groups of coherent peoples, “optimally” homogeneous by virtue of their traditions, their geography, their ethno-cultural components.

“The nation,” writes François Perroux,

[a] living and dynamic reality, becomes one of the essential sources of energy to restructure global society and its economy […]. The earthbound coagulate into armed nations, into empires, into hesitant communities, trying economically to form regions of nations (Bertrand Russell). One finds these assemblies—neither closed, which is impossible, nor unreservedly welcoming […]. In these associations of nations, there must be collective projects of infrastructure, investment, distribution of products and of revenues. It’s to the degree that these nations, witnesses and defenders of peoples, favour this deconcentration of economic powers and this decentralisation of their effects, that a certain reciprocity of development is outlined, which is not spontaneously generated by the interplay of private interests [Le Monde de l'économie, 9 October 1979].

These associations of nations are geopolitically possible, and they rupture current economic-strategic confines. Each great planetary region might thus be seen to coincide, in its living-space, with a related cultural heritage, a community of political interests, a certain ethnic and historic homogeneity, and macroeconomic factors that make possible, in time, autonomous development without recourse to international beggary.* A new nomos of the earth, to borrow Carl Schmitt’s expression, might thus see the light of day, founded on a society of communities, and no longer on a pseudo-community of societies.

[* Author’s note. For certain liberal economists, aid to underdeveloped countries ought, it’s true, be limited to aiding firms that invest in those countries. “By making aid to the Third World benefit industry,” said a senior French functionary, “we might at last make aid to industry benefit the Third World.”]

But these cultures, one could say, would no longer communicate with one another. Precisely the inverse is true. In communicating with one another with Western civilisation as a common reference, cultures in fact establish a pseudo-communication. This common reference in effect alienates the personality of those that use it. The signifier (Western cultural language) substitutes itself for the signified (the local culture that tries to express itself in Western language). In short, peoples know themselves less and less closely; cultures no longer communicate, and no longer manage to enrich themselves, because they use an infra-cultural Esperanto which belongs to anybody and everybody. Sharing in the same customs of language, dress, diet, etc., man can no longer perceive the specificities of his fellow man—where they survive. An Italian in Thailand will use English, descend on an international hotel, and will only see Thai customs as marginalised folklore. If he goes to Africa, the Africans with whom he mingles will be “three-piece-suit-briefcases” (costards-trois-pièces-attaché-case), in the pungent words of the Ivorian lawyer Badibanga. What will he know of African man? On the other hand, when Marco Polo arrived in China, the communication was real and fertile, despite the absence of common reference; and the influence of Chinese culture was significant in Europe thereafter. Cultures are incommensurable: they can only be understood from within; but they might influence “from the wings,” and profit by contact—not by mixture. The idea of the interpenetration of cultures, or the mechanist illusion of a universal measure of the “best” of cultures, an idea defended notably by Léopold Senghor, can bring about nothing but the impoverishment of all cultures, and the enforcement of Western infra-cultural language. Language alienates because it doesn’t rest on the anthropological support of any people; and in this respect, it doesn’t bear any meaning.

For Martin Heidegger, the term Western doesn’t express the essence of Europe. He prefers to use the enigmatic word Hesperian to denote the essence of European modernity—or, more precisely, its possible future, its virtuality. The advent of the Hesperian therefore presupposes the death, in Europe, of the Western.

Appendices

[Translator's note. These appeared as highlighted inserts in the original.]

1. There Is No “White World”

All dominant ideologies oppose, in their discourse, the Third World and the West. Whatever criteria be taken into account, these definitions all function according to the same principle of exclusion. Christianity was the first to thus oppose infidels and believers, perpetuating across centuries the Manichaean vision of the world. In the eighteenth century, the noble savage may well have known a paradisiacal existence: he nonetheless remains a “savage,” to which philosophers this time oppose the civilised. Inverting this proposition, rationalism in its turn distinguishes civilised Western peoples from uncivilised peoples. In their analysis of economic growth, liberal theories have themselves merely opposed the developed West to the developing Third World. Be they right or left, progressive or reactionary, occidentalist ideologies remain in submission to this Manichaean logic. Occidentalism negates the identity of the Other, which it perceives in the end as non-Christian, uncivilised or undeveloped…without imagining for a second that this Other might simply be itself. This repudiation of difference marks an essentially racist course. Implicitly, it’s always the white world that opposes itself to the world of colour. The very notion of the West is in fact the product of an ideology, and contains no geopolitical, cultural, or even economic reality (how to class Argentina—white developing country?—or Japan—hyper-developed country of colour?). These words are not neutral. The concept of the West ensnares who uses it. To speak of the West is, in the end, to recognise its existence and to admit the logic it carries. It’s to adopt implicitly the ideology of which it’s the product.

2. Decolonisation Must Be Redone

Is the Westernisation of the planet itself, as we generally assert, the historical consequence of European colonialism? Very widespread in progressive milieus, this thesis doesn’t seem particularly accurate. European colonialism, as manifested from the sixteenth to twentieth centuries, must in fact be clearly distinguished from the Western neo-colonialism that succeeded it. Traditional European colonialism expressed a hegemonic and imperial will, which needn’t entail the destruction of the values of the colonised. But from the nineteenth century, European colonialism was also the articulation of a “civilising” will, stemming from the philosophical universalism of the century of Enlightenment, which urged the coloniser to assimilate the colonised, and dispossess him of his values. In condemning, in the name of a humanist and Messianic ethic, the hegemonic and imperial will of European powers, the United States contributed in a decisive way to the dismantling of colonial empires. Not that they might free the colonised peoples, but to substitute for the traditional colonial order, essentially political, a neo-colonialism retaining nothing of colonialism but the “civilising” will. Thus “Westernised,” neo-colonialism does nothing but entrench the dangers that the old European colonialism brought down on the identity of colonised peoples. It’s thus that those peoples, having just escaped European colonial influence, find themselves irresistibly suppressed by Western neo-colonialism, without these people able to resist it. How, indeed, can they revolt against the network of influences that enfolds local bourgeoisies, multinationals, political milieus, etc.? When a master is visible, one might recognise him as an enemy and free oneself; but neo-colonialism submits peoples to a “system of live,” and no longer to the political power of another nation, as in traditional European colonialism. How can one combat a phantom coloniser? The answer reveals itself: “neo-decolonisation” must be metapolitical and cultural.

3. When the West Forgot Greece

It’s in Der Spruch des Anaximander, an exegetical text on a fragment of pre-Socratic philosophy, that Martin Heidegger introduces the concept of Abend-Land. He opposes it to Abendland (West) and, in the translation of Wolfgang Brockmeier, Abend-Land has been very happily rendered by Hespérie (Hesperia) and hespérial (Hesperian). Hesperia is, as the Greek root indicates, the land of sunset. But it doesn’t denote the West, nor the western regions of the world, but rather a project of world-organisation bearing the marks of sunset—that is, of the fulfilment of an auroral worldview, expressed in the seventh century before our era by the first European thinker. Heidegger writes: “The greatest event begins: the forgetfulness of being, in which Hesperian world-History comes and goes.” For Heidegger, European man has been by turns “Greek,” “Christian,” “modern,” “planetary,” or even “Western” or “American”; he must today become “Hesperian”:

“The antiquity that brings about the words of Anaximander,” writes Heidegger,

[b]elongs to the morning of the dawn of Hesperia […]. If we persist so obstinately in thinking the thought of the Greeks as the Greeks knew to think it, it’s not for love of the Greeks: it’s to rediscover this Identical which, in diverse guises, concerns the Greeks and concerns us historically. It’s that, which carries the dawn of thought into the destiny of the Hesperian. It’s in conformity with this destiny that only the Greeks become the Greeks, in a historical sense. Destiny awaits what becomes of its seed.

The Hesperian represents, at the same time, the sunset of the Greek metaphysical tradition and the virtual beginning of another cycle which fulfils Greek thought at another level—that of self-conscious will-to-power. The Hesperian is thus at once a restarting, a deep return to the dawn—that is, to the Greek conception of the world—and a rupture with the Western, which has itself forgotten Greece. Returning to Hesperia, for us Europeans, consists, then, in fulfilling our will-to-power as Europeans, conscious of our Greek heritage, and no longer as Westerners, forgetful of that heritage. The Hesperian is the European who becomes conscious that he’s Greek, and who therefore rejects the West as non-Greek, and ends by forgetting himself; who will have “meditated on the disarray of the present destiny of the world”; and will consciously fulfil the Greek vision of the world.

00:16 Publié dans Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : guillaume faye, nouvelle droite, civilisation occidentale, occidentisme, occidentalisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook