In 1975, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn excised the several Lenin chapters from his massive and unfinished Red Wheel epic and compiled them into one volume entitled Lenin in Zürich. At the time, only one of these chapters had been published — in Knot I of the Red Wheel, known as August 1914 — while the remaining chapters would still have to languish in the author’s desk drawer for decades before appearing as part of The Red Wheel proper (November 1916 and March 1917, specifically). In order to save time and make an impression on his contemporaries, many of whom in the West still harbored misplaced sympathies for Lenin, Solzhenitsyn decided to share with the world his eye-opening and unforgettable treatment of the Soviet Revolutionary.

In 1975, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn excised the several Lenin chapters from his massive and unfinished Red Wheel epic and compiled them into one volume entitled Lenin in Zürich. At the time, only one of these chapters had been published — in Knot I of the Red Wheel, known as August 1914 — while the remaining chapters would still have to languish in the author’s desk drawer for decades before appearing as part of The Red Wheel proper (November 1916 and March 1917, specifically). In order to save time and make an impression on his contemporaries, many of whom in the West still harbored misplaced sympathies for Lenin, Solzhenitsyn decided to share with the world his eye-opening and unforgettable treatment of the Soviet Revolutionary.

Solzhenitsyn’s approach, which was based on close study of Lenin’s speeches and letters as well as few accounts of his exile in Switzerland, combines third-person narration and first-person intimacy to deliver a nearly-Satanic depiction of Lenin at that time. Lenin is peevish, intolerant, tyrannical, ideologically murderous, and astoundingly petty. He’s also brilliant, dedicated, focused, and consumed by inhuman energy. It’s both fiction and not, and, as with the entire Red Wheel saga, demonstrates how Solzhenitsyn used the narrative arts to reconstruct and decipher historical events.

Lenin in Zürich’s enduring meaning for the Right lies not so much in Solzhenitsyn’s negative portrayal of Lenin, the memory of whom most Rightists would rather smash with a pedestal than hold up with one. Lenin’s ruthlessness and cruelty as a world leader is well documented. Rather, Solzhenitsyn cuts open, as only a novelist could, the repulsive psychological innards of the nation-killing Left, thereby defining the Right as its opposite in comparison.

We feel the strain, first off. Through his Nietzschean use of exclamation points and the constant stream of insults he hurls, unspoken, at his fellow socialists, Lenin never seems to enjoy being Lenin. He resembles Milton’s Lucifer cast down to Hell in Paradise Lost, only he’s stuck in Zurich, a place so peaceful, so prosperous, so bourgeois, so pleased with itself — in the middle of a world war, no less — that Lenin could just spit. Even the socialists there are incompetent, blockheaded vacillators. All Lenin can do is study the newspapers, plot unlikely ways in which the war could instigate communist revolutions, and fulminate. But mostly, he fulminates.

But worst of all, obscenest of all, Kautsky, with his false, hypocritical, sneaking devotion to principle, had started squawking like an old hen. What a vile trick: setting up a “socialist court” to try the Russian Bolsheviks, and ordering them to burn the all-powerful five-hundred-ruble notes! (Lenin had only to see a picture of that hoary-headed holy man in his goggling glasses, and he retched as though he had found himself swallowing a frog.)

August 1914 was a low point for the Bolsheviks abroad, apparently. They had few prospects and constantly bickered among themselves. That many on the Swiss Left were hampered by quaint notions of nationalism infuriated Lenin, but there was little he could do about it. After the failed Russian revolution in 1905, expectations were low — that is, until world war is declared. Solzhenitsyn’s first indication of how the Left operates against humanity, almost like a cancer, appears when Lenin reveals how overjoyed he is with the war. Death and destruction mean nothing to him unless it helps the Cause. He sees the struggle on the Left as patriots vs. anti-patriots — but on a larger scale, his revolutionary framework pits nationalists against anti- (or super-) nationalists. And nothing can weaken nationalism more than a senseless and protracted war. At one point, he ghoulishly admits that the greater the number killed in battle, the happier he gets. He worries only that the European leaders would do something stupid and ghastly like sue for peace before he and his fellows could instigate revolution in teetering-on-the-brink nations such as Switzerland and Sweden.

The little things that Lenin does, and many of his offhand remarks and observations, also reveal his enmity towards everything traditional, natural, and morally wholesome. He complains bitterly against the principle of property rights. He recoils when approached by nuns on a train platform. He endeavors to keep his colleagues quarreling when it is useful to him. He opposes the Bolshevik employment of individual terror only because he believes terror should be a “mass activity.” He passes shops and delicatessens on the street and imagines them being smashed by an axe-wielding mob. He even foreshadows the Soviet Dekulakization of the next decade by claiming that

The Soviet must try to ally itself not with the peasantry at large but first and foremost with the agricultural labourers and the poorest peasants, separating them from the more prosperous. It is important to split the peasantry right now and set the poor against the rich. That is the crux of the matter.

Lenin not only pits himself against mankind, he pits himself irrevocably against his own colleagues. When he meets with the Swiss Social Democrats (dubbed “the Skittles Club”) at a restaurant, Solzhenitsyn offers this diabolic nugget:

Lenin’s gaze slides rapidly, restlessly over all those heads, so different, yet all so nearly his for the taking.

They all dread his lethal sarcasm.

And don’t get him started on the Mensheviks. He hates the Mensheviks. At one point, Lenin rather hilariously avers that he “would sooner see Tsarism survive another thousand years than give a millimetre to the Mensheviks!”

He also lies. He announces that Switzerland is an imperialist country when he knows it isn’t. He also claims, to the bafflement of the Swiss socialists, that Switzerland is the most revolutionary country in the world. He makes false promises to the more moderate socialists regarding their post-revolutionary roles. Double standards are nothing to him as well. He advocates opposing the war in public but egging it on in private. He professes to support democracy, but only before the revolution. Afterward, it should be abolished with all other hindrances to his planned totalitarian rule.

If any of this sounds familiar, it should. The Left has not changed much since Lenin’s day, merely exchanging class for race in the twenty-first century. The same bunch that clamored for civil rights for non-whites in the 1960s are now calling for the open oppression of whites. Just as with Lenin, what the Left says it wants and what it truly wants are two different things — the only determining factor here being who wields the power. Furthermore, a stroll through anti-white Twitter or anti-white Hollywood will show quite clearly that Left’s violent fantasies against their perceived enemies aren’t going anywhere.

Another aspect of the Left that Solzhenitsyn reveals is its Jewishness. True, he does not name the Jew in Lenin in Zürich like he does in 200 Years Together. However, since all the characters in these chapters are historical figures, it’s easy enough to gauge exactly how Jewish Lenin’s circle was and how important some of these Jews were to his — and the Bolsheviks’ — ultimate success. And the answer is considerable on both counts.

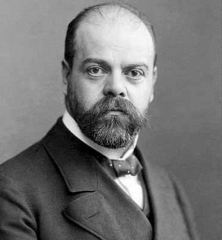

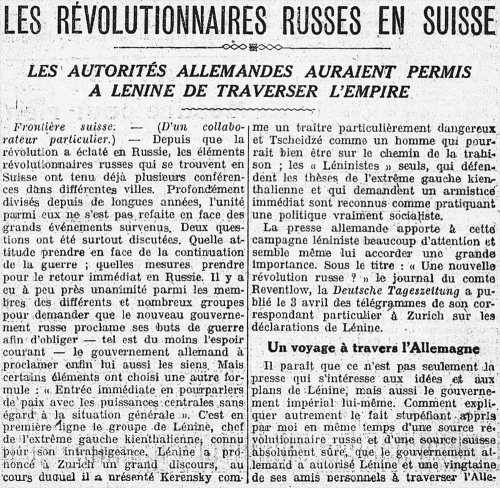

A man known as Parvus appears foremost among the Jews in Lenin in Zürich. Born Izrail Lazarevich Gelfand, he comes across, at least to Lenin, as an enigmatic and somewhat unscrupulous capitalist and millionaire who, for some reason, dedicates his life to socialist causes. Either this, or he wishes to destroy Russia while exhibiting a suspicious allegiance to Germany. Parvus, along with his protégé Leon Trotsky, had tried and failed to overthrow the Tsar in 1905, and now offers a new plan: With his deep contacts in the German government, he will arrange for the Bolsheviks’ to travel through Germany in order to re-enter Russia where they can foment revolution against a weakened Tsar. This would serve not only Lenin but Parvus’ German friends as well by knocking Russia out of the war. Suspicious of Parvus’ outsider status, and especially of his tolerance of Lenin’s detested Mensheviks, Lenin at first refuses. However, he cannot shake his respect and fascination for this mysterious benefactor.

A man known as Parvus appears foremost among the Jews in Lenin in Zürich. Born Izrail Lazarevich Gelfand, he comes across, at least to Lenin, as an enigmatic and somewhat unscrupulous capitalist and millionaire who, for some reason, dedicates his life to socialist causes. Either this, or he wishes to destroy Russia while exhibiting a suspicious allegiance to Germany. Parvus, along with his protégé Leon Trotsky, had tried and failed to overthrow the Tsar in 1905, and now offers a new plan: With his deep contacts in the German government, he will arrange for the Bolsheviks’ to travel through Germany in order to re-enter Russia where they can foment revolution against a weakened Tsar. This would serve not only Lenin but Parvus’ German friends as well by knocking Russia out of the war. Suspicious of Parvus’ outsider status, and especially of his tolerance of Lenin’s detested Mensheviks, Lenin at first refuses. However, he cannot shake his respect and fascination for this mysterious benefactor.

Fat, ostentatious, and lacking tact, Parvus appears just as repulsive to the reader as he does to Lenin. However, his great wealth and his acumen for political scheming tames Lenin’s rapacious attitude and manages to shut him up for a while (which perhaps exonerates him somewhat as a character in the reader’s mind). He’s also quite prescient, having predicted World War I at an earlier point and impressing upon an incredulous Lenin that “the destruction of Russia now held the key to the future history of the world!”

And, of course, he’s a financial genius:

It was a matter of instinct with him, the emergence of disproportions, imbalances, gaps which begged him, cried out to him to insert his hand and extract a profit. This was so much part of his innermost nature that he conducted his multifarious business transactions, which by now were scattered over ten European countries, without a single ledger, keeping all the figures in his head.

Another Jew who figures prominently in Lenin in Zürich is Radek (born Karl Berngardovich Sobelsohn). Lenin has tremendous respect for Radek as a writer and propagandist — that Radek had become one of the Soviet Union’s most prominent journalists years after Lenin’s death certainly justifies Lenin’s esteem. In all, he is clever and resourceful and the only person to whom Lenin would voluntarily surrender his pen. After the February Revolution in Russia, as Lenin prepares for travel back to his home country according to Parvus’ plan, Radek contrives ingenious solutions to formidable logistical problems that threaten to sink the enterprise. This makes Lenin, for one of the few times in the book, truly happy.

Another Jew who figures prominently in Lenin in Zürich is Radek (born Karl Berngardovich Sobelsohn). Lenin has tremendous respect for Radek as a writer and propagandist — that Radek had become one of the Soviet Union’s most prominent journalists years after Lenin’s death certainly justifies Lenin’s esteem. In all, he is clever and resourceful and the only person to whom Lenin would voluntarily surrender his pen. After the February Revolution in Russia, as Lenin prepares for travel back to his home country according to Parvus’ plan, Radek contrives ingenious solutions to formidable logistical problems that threaten to sink the enterprise. This makes Lenin, for one of the few times in the book, truly happy.

Not included in the later editions of The Red Wheel, which contain all of the Lenin in Zürich chapters, is an extremely useful “Author’s Index of Names” in the back of the book. Forty-nine names are mentioned, fifteen of which are Jews — sixteen if we include the half-Jewish Ryazanov (David Borisovich Goldendakh). This is over thirty percent, with a couple of names that I could not verify one way or the other. The ones I could are: Aleksandr Abramovich, Moisei Bronski, Grigory Chudnovsky, Lev Kamenev, Moisei Kharitonov, Paul Levi, Maksim Litvinov, Yuly Martov, Parvus, Radek, Georgy Shklovsky, Georg Sklarz, Grigory Sokolnikov, Moisei Uritsky, and Grigory Zinoviev.

Further, not all of the gentiles mentioned were part of Lenin’s inner circle. Some, such as the much-despised Robert Grimm and Fritz Platten, were Swiss socialists who contended with Lenin and did not accompany him to Russia. Others, such as Aleksandr Shlyapnikov and Nikolai Bukharin, were important and were mentioned frequently in the text but were not in Switzerland during the timeframe of the chapters. And two, Nadezhda Krupskaya (his neglected wife) and Inessa Armand (his beloved mistress) made few substantive contributions to his revolutionary work in the pages of Lenin in Zürich. According to Solzhenitsyn, many of Lenin’s closest associates in Zurich were Jews. Certainly, the two most important ones were.

From the perspective of the Right, Solzhenitsyn offers tantalizing evidence that the October Revolution would not have occurred (or would not have been as successful) without crucial actions from Jews at the most important moments. Without Parvus and Radek, Lenin likely would have stayed in Zurich in March 1917. Would he have gotten out in April or May or at all? Would he have even made it to Russia in time to make a difference? Would the Bolsheviks have been as successful without him? Impossible to say, but a reasonable conclusion would be that the fate of the Soviet Union would have hung much more in the balance without Lenin running things during its formative years. And without a successful October Revolution, we likely wouldn’t have the tens of millions of people senselessly killed by the Soviets during the 1920s and 1930s.

Lenin in Zürich offers positive value to the Right as well, almost to the point of irony. Despite being an unhinged, foul-tempered, miserable villain, Solzhenitsyn’s Lenin exhibits some admirable characteristics that dissidents of any stripe would do well to emulate — provided they sift out the destructive elements. His gargantuan faith in himself makes him utterly impervious to ridicule and embarrassment. He thinks in slogans — always striving for a way to control and motivate the masses. (“The struggle against war is impossible without socialist revolution!”) He’s obsessed with time and gets annoyed almost to the point of rage whenever he wastes any. Everything is urgent for him. The man also demonstrates inhuman energy, always working, always reading, always striving. Solzhenitsyn, to his great credit as an author, makes Lenin’s intensity vibrate on nearly every page. Here’s a sample:

By analogy, by association, by contradiction, sparks of thought were continually struck off, flying at a tangent to left or right, on to loose scraps of paper, on to the lined pages of exercise books, into blank margins, and every thought must be stitched to paper with a fiery thread before it could fade, to smoulder there until it was wanted, in a draft summary or else in a letter begun there and then so that he could forge his sentences red-hot.

In essence, Lenin’s bulletproof spiritual constitution makes him the perfect radical machine. Who wouldn’t want to follow such a man during a crisis?

But to afford this, Lenin must live a Spartan life. He dedicates his entire life for his cause, and so does little for himself in terms of pleasure. Sadly for him, and for humanity, his dear Inessa could not requite his infatuation with her. In a candid moment, Lenin admits that only in her presence could he slow down and relax and do things for himself — day after gloriously languid day. Perhaps if he had found a little more solace with her, the world could have been spared his Mephistophelean wrath. Perhaps with her, he could have been more human and less Lenin.

Here is where I believe Solzhenitsyn fibs in the way all great authors should fib. This is all too good, too perfect a story to tell. I sense an all-encompassing tragic architecture rather than the ramshackle formation of truth. I can’t prove it, but I would guess that Vladimir Lenin would have remained a devourer of worlds even if he had had his way with Inessa every night while in Zurich. He would have eventually grown bored and contemptuous of her, like he did with most everyone else. Nothing would have changed.

But Solzhenitsyn makes us wish it had. And he makes us believe, even if only for a moment, that through romantic love it could have. When Lenin has an introspective moment alone, shortly after learning of the first revolution in Russia, he contemplates how his life is going to change forever. He then sits on a park bench before an obelisk commemorating a 1799 Zurich battle between the Russians and Austrians and the French. Yes, Russians of the past had fought even here, he thinks.

The clip-clop of hooves startles him. Inessa! Here she comes! What a surprise! She’s sitting upright in the saddle of a chestnut horse. She’ll be with him at any moment!

Of course, it isn’t her, but a beautiful woman nonetheless. And this gets our Lenin to thinking. . .

He sat very still studying her face and the hair like a black wing peeping under her hat.

If he could suddenly liberate his mind from all the work that needed to be and must be done — how beautiful this would seem! A beautiful woman!

Her only movement was the swaying of shoulders and hips as the sway of the horse lifted her toe-caps in the stirrups.

She rode on downhill to a turn in the road — and there was nothing but the rhythm of hooves for a little while longer.

She rode on, carrying a little part of him away with her.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [2] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.