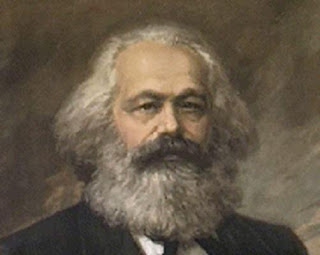

There is much about The Communist Manifesto [2] that is valid from a Rightist viewpoint – if analyzed from a reactionary perspective. One does not need to be a Marxist to accept that a dialectical interpretation of history is one of several methods by which history can be studied, albeit not in a reductionist sense, but in tandem with other methods such as, in particular, the cyclical morphology of Oswald Spengler,[1] the economic morphology of civilizations as per Brooks Adams,[2] the cultural vitalism of Yockey,[3] and the heroic vitalism of Carlyle.[4] Marx, after all, did not conceive dialectics, he appropriated the theory from Hegel, who had followers from both Left and Right, and whose doctrine was not that of the materialism of the Left. The American Spenglerian, Francis Parker Yockey, pointed this out:

Being inwardly alien to Western philosophy, Marx could not assimilate the ruling philosopher of his time, Hegel, and borrowed Hegel’s method to formulate his own picture. He applied this method to capitalism as a form of economy, in order to bring about a picture of the Future according to his own feelings and instincts.[5]

Indeed, Marx himself repudiated Hegel’s dialectics, whose concept of “The Idea” seemed of a religious character to Marx, who countered this metaphysical “Idea” with the “material world”:

My dialectic method is not only different from the Hegelian, but is its direct opposite. To Hegel, the life-process of the human brain, i.e. the process of thinking, which, under the name of “the Idea,” he even transforms into an independent subject, is the demiurgos of the real world, and the real world is only the external, phenomenal form of “the Idea.” With me, on the contrary, the ideal is nothing else than the material world reflected by the human mind, and translated into forms of thought.[6]

Hegel, on the other hand, wrote about how the historical dialectic worked on the “national spirit,” his philosophy being a part of the Rightist doctrinal stream that was receiving an important impetus form the German thinkers in antithesis to “English thought” based on economics, which imbued Marx’s thinking and hence mirrored capitalism. Hegel wrote, for example:

The result of this process is then that Spirit, in rendering itself objective and making this its being an object of thought, on the one hand destroys the determinate form of its being, on the other hand gains a comprehension of the universal element which it involves, and thereby gives a new form to its inherent principle. In virtue of this, the substantial character of the National Spirit has been altered, – that is, its principle has risen into another, and in fact a higher principle.

It is of the highest importance in apprehending and comprehending History to have and to understand the thought involved in this transition. The individual traverses as a unity various grades of development, and remains the same individual; in like manner also does a people, till the Spirit which it embodies reaches the grade of universality. In this point lies the fundamental, the Ideal necessity of transition. This is the soul – the essential consideration – of the philosophical comprehension of History.[7]

Dialectically, the antithesis, or “negation” as Hegel would have called it, of Marxism is “Reactionism,” to use Marx’s own term, and if one applies a dialectical analysis to the core arguments of The Communist Manifesto, a practical methodology for the sociology of history from a Rightist perspective emerges.

Conservatism and Socialism

In English-speaking states at least, there is a muddled dichotomy in regard to the Left and Right, particularly among media pundits and academics. What is often termed “New Right” or “Right” there is the reanimation of Whig-Liberalism. If the English wanted to rescue genuine conservatism from the free-trade aberration and return to their origins, they could do no better than to consult the early twentieth-century philosopher Anthony Ludovici, who succinctly defined the historical dichotomy rather than the commonality between Toryism and Whig-Liberalism, when discussing the health and vigor of the rural population in contrast to the urban:

In English-speaking states at least, there is a muddled dichotomy in regard to the Left and Right, particularly among media pundits and academics. What is often termed “New Right” or “Right” there is the reanimation of Whig-Liberalism. If the English wanted to rescue genuine conservatism from the free-trade aberration and return to their origins, they could do no better than to consult the early twentieth-century philosopher Anthony Ludovici, who succinctly defined the historical dichotomy rather than the commonality between Toryism and Whig-Liberalism, when discussing the health and vigor of the rural population in contrast to the urban:

. . . and it is not astonishing therefore that when the time of the Great Rebellion[8] the first great national division occurred, on a great political issue, the Tory-Rural-Agricultural party should have found itself arrayed in the protection and defence of the Crown, against the Whig-Urban-Commercial Trading party. True, Tory and Whig, as the designation of the two leading parties in the state, were not yet known; but in the two sides that fought about the person of the King, the temperament and aims of these parties were already plainly discernible.

Charles I, as I have pointed out, was probably the first Tory, and the greatest Conservative. He believed in securing the personal freedom and happiness of the people. He protected the people not only against the rapacity of their employers in trade and manufacture, but also against oppression of the mighty and the great . . .[9]

It was the traditional order, with the Crown at the apex of the hierarchy, which resisted the money-values of the bourgeoisie revolution, which manifested first in England and then in France, and over much of the rest of mid-nineteenth century Europe. The world remains under the thrall of these revolutions, as also under the Reformation that provided the bourgeoisie with a religious sanction.[10]

As Ludovici pointed out, in England at least, and therefore as a wider heritage of the English-speaking nations, the Right and the free trade liberals emerged as not merely ideological adversaries, but as soldiers in a bloody conflict during the seventeenth century. The same bloody conflict manifested in the United States in the war between the North and South, the Union representing Puritanism and its concomitant plutocratic interests in the English political sense; the South, a revival of the cavalier tradition, ruralism and the aristocratic ethos. The South itself was acutely aware of this tradition. Hence, when in 1863 Confederate Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin was asked for ideas regarding a national seal for the Confederate States of America, he suggested “a cavalier” based on the equestrian statue of Washington in Capitol Square at Richmond, and stated:

It would do just honor to our people. The cavalier or knight is typical of chivalry, bravery, generosity, humanity, and other knightly virtues. Cavalier is synonymous with gentleman in nearly all of the modern languages . . . the word is eminently suggestive of the origin of Southern society as used in contradistinction to Puritan. The Southerners remain what their ancestors were, gentlemen.[11]

This is the historical background by which, much to Marx’s outrage, the remnant of the aristocracy sought anti-capitalist solidarity with the increasingly proletarianized and urbanized peasants and artisans in common opposition to capitalism. To Marx, such “Reactionism” (sic) was an interference with the dialectical historical process, or the “wheel of history,” as will be considered below, since he regarded capitalism as the essential phase of the dialectic leading to socialism.

Spengler, one of the seminal philosopher-historians of the “Conservative Revolutionary” movement that arose in Germany in the aftermath of the First World War, was intrinsically anti-capitalist. He and others saw in capitalism and the rise of the bourgeoisie the agency of destruction of the foundations of traditional order, as did Marx. The essential difference is that the Marxists regarded it as part of a historical progression, whereas the revolutionary conservatives regarded it as a symptom of decline. Of course, since academe is dominated by mediocrity and cockeyed theories, this viewpoint is not widely understood in (mis)educated circles.

Spengler, one of the seminal philosopher-historians of the “Conservative Revolutionary” movement that arose in Germany in the aftermath of the First World War, was intrinsically anti-capitalist. He and others saw in capitalism and the rise of the bourgeoisie the agency of destruction of the foundations of traditional order, as did Marx. The essential difference is that the Marxists regarded it as part of a historical progression, whereas the revolutionary conservatives regarded it as a symptom of decline. Of course, since academe is dominated by mediocrity and cockeyed theories, this viewpoint is not widely understood in (mis)educated circles.

Of Marxism, Spengler stated in his essay devoted specifically to the issue of socialism:

Socialism contains elements that are older, stronger, and more fundamental than his [Marx’s] critique of society. Such elements existed without him and continued to develop without him, in fact contrary to him. They are not to be found on paper; they are in the blood. And only the blood can decide the future.[12]

In The Decline of The West [3], Spengler states that in the late cycle of a civilization there is a reaction against the rule of money, which overturns plutocracy and restores tradition. In Late Civilization, there is a final conflict between blood and money:

. . . [I]f we call these money-powers “Capitalism,” then we may designate as Socialism the will to call into life a mighty politico-economic order that transcends all class interests, a system of lofty thoughtfulness and duty-sense that keeps the whole in fine condition for the decisive battle of its history, and this battle is also the battle of money and law. The private powers of the economy want free paths for their acquisition of great resources . . .[13]

In a footnote to the above, Spengler reminded readers regarding “capitalism” that, “in this sense the interest-politics of the workers’ movements also belong to it, in that their object is not to overcome money-values, but to possess them.” Concerning this, Yockey stated:

The ethical and social foundations of Marxism are capitalistic. It is the old Malthusian “struggle” again. Whereas to Hegel, the State was an Idea, an organism with harmony in its parts, to Malthus and Marx there was no State, but only a mass of self-interested individuals, groups, and classes. Capitalistically, all is economics. Self-interest means: economics. Marx differed on this plane in no way from the non-class war theoreticians of capitalism – Mill, Ricardo, Paley, Spencer, Smith. To them all, Life was economies, not Culture… All believe in Free Trade and want no “State interference” in economic matters. None of them regard society or State as an organism. Capitalistic thinkers found no ethical fault with destruction of groups and individuals by other groups and individuals, so long as the criminal law was not infringed. This was looked upon as, in a higher way, serving the good of all. Marxism is also capitalistic in this . . .[14]

Something of the “ethical socialism” propounded by Rightists such as Spengler and Yockey is also alluded to in the above passage: “It is based on the State [as] an Idea, an organism with harmony in its parts,” anathema to many of today’s self-styled “conservatives,” but in accord with the traditional social order in its pre-materialistic epochs. It is why Rightists, prior to the twentieth-century reanimated corpse of nineteenth-century free trade, advocated what Yockey called “the organic state” in such movements as “corporatism,” which gave rise to the “New States” during the 1930s, from Salazar’s Portugal and Dollfuss’ Austria to Vargas’ Brazil. Yockey summarizes this organic social principle: “The instinct of Socialism however absolutely preludes any struggle between the component parts of the organism.”[15] It is why one could regard “class struggle” literally as a cancer, whereby the cells of the organism war among themselves until the organism dies.

Caste & Class

The “revolutionary conservatism” of Spengler and others is predicated on recognizing the eternal character of core values and institutions that reflect the cycle of cultures in what Spengler called their “spring” epoch.[16] A contrast in ethos and consequent social order between traditional (“spring”) and modern (“winter”) cycles of a civilization is seen in such manifestations as caste as a metaphysical reflection of social relations,[17] as distinct from class as an economic entity.

Organizationally, the guilds or corporations were a manifestation of the divine order which, with the destruction of the traditional societies, were replaced by trade unions and professional associations that aim only to secure the economic benefits of members against other trades and professions, and which seek to negate the duty and responsibility one had in being a proud member of one’s craft, where a code of honor was in force. Italian “revolutionary conservative” philosopher Julius Evola stated of this that, like the corporations of Classical Rome, the medieval guilds were predicated on religion and ethics, not on economics.[18] “The Marxian antithesis between capital and labor, between employers and employees, at the time would have been inconceivable.”[19] Yockey stated:

Marxism imputed Capitalistic instincts to the upper classes, and Socialistic instincts to the lower classes. This was entirely gratuitous, for Marxism made an appeal to the capitalistic instincts of the lower classes. The upper classes are treated as the competitor who has cornered all the wealth, and the lower classes are invited to take it away from them. This is capitalism. Trade unions are purely capitalistic, distinguished from employers only by the different commodity they purvey. Instead of an article, they sell human labor. Trade-unionism is simply a development of capitalistic economy, but it has nothing to do with Socialism, for it is simply self-interest.[20]

The Myth of “Progress”

While Western Civilization prides itself on being the epitome of “progress” through its economic activity, it is based on the illusion of a Darwinian lineal evolution. Perhaps few words have more succinctly expressed the antithesis between the modernist and the traditional conservative perceptions of life than the ebullient optimism of the nineteenth century biologist, Dr. A. R. Wallace, when stating in The Wonderful Century [4] (1898):

Not only is our century superior to any that have gone before it but . . . it may be best compared with the whole preceding historical period. It must therefore be held to constitute the beginning of a new era of human progress. . . . We men of the 19th Century have not been slow to praise it. The wise and the foolish, the learned and the unlearned, the poet and the pressman, the rich and the poor, alike swell the chorus of admiration for the marvellous inventions and discoveries of our own age, and especially for those innumerable applications of science which now form part of our daily life, and which remind us every hour or our immense superiority over our comparatively ignorant forefathers.[21]

Not only is our century superior to any that have gone before it but . . . it may be best compared with the whole preceding historical period. It must therefore be held to constitute the beginning of a new era of human progress. . . . We men of the 19th Century have not been slow to praise it. The wise and the foolish, the learned and the unlearned, the poet and the pressman, the rich and the poor, alike swell the chorus of admiration for the marvellous inventions and discoveries of our own age, and especially for those innumerable applications of science which now form part of our daily life, and which remind us every hour or our immense superiority over our comparatively ignorant forefathers.[21]

Like Marx’s belief that Communism is the last mode of human life, capitalism has the same belief. In both worldviews, there is nothing other than further “progress” of a technical nature. Both doctrines represent the “end of history.” The traditionalist, however, views history not as a straight line from “primitive to modern,” but as one of continual ebb and flow, of cosmic historical tides, or cycles. While Marx’s “wheel of history” moves forward, trampling over all tradition and heritage until it stops forever at a grey, flat wall of concrete and steel, the traditionalist “wheel of history” revolves in a cycle on a stable axis, until such time as the axis rots – unless it is sufficiently oiled or replaced at the right time – and the spokes fall off;[22] to be replaced by another “wheel of history.”

Within the Western context, the revolutions of 1642, 1789, and 1848, albeit in the name of “the people,” sought to empower the merchant on the ruins of the Throne and the Church. Spengler writes of the later era: “. . . And now the economic tendency became uppermost in the stealthy form of revolution typical of the century, which is called democracy and demonstrates itself periodically, in revolts by ballot or barricaded on the part of the masses.” In England, “. . . the Free Trade doctrine of the Manchester School was applied by the trades unions to the form of goods called ‘labour,’ and eventually received theoretical formulation in the Communist Manifesto of Marx and Engels. And so was completed the dethronement of politics by economics, of the State by the counting-house . . .”[23]

Spengler calls Marxian types of socialism “capitalistic” because they do not aim to replace money-based values, “but to possess them.” Concerning Marxism, he states that it is “nothing but a trusty henchman of Big Capital, which knows perfectly well how to make use of it.”[24] Further:

The concepts of Liberalism and Socialism are set in effective motion only by money. It was the Equites, the big-money party, which made Tiberius Gracchus’ popular movement possible at all; and as soon as that part of the reforms that was advantageous to themselves had been successfully legalized, they withdrew and the movement collapsed.

There is no proletarian, not even a communist, movement that has not operated in the interests of money, in the directions indicated by money, and for the time permitted by money – and that without the idealist amongst its leaders having the slightest suspicion of the fact.[25]

It is this similarity of spirit between capitalism and Marxism that has often manifested in the subsidy of “revolutionary” movements by plutocracy. Some plutocrats are able to discern that Marxism and similar movements are indeed useful tools for the destruction of traditional societies that are hindrances to global profit maximization. One might say in this sense that, contrary to Marx, capitalism is not a dialectical stage leading to Communism, but that Marxian-style socialism is a dialectical phase leading to global capitalism.[26]

Capitalism in Marxist Dialectics

While what is popularly supposed to be the “Right” is upheld by its adherents as the custodian of “free trade,” which in turn is made synonymous with “freedom,” Marx understood the subversive character of free trade. Spengler cites Marx on free trade, quoting him from 1847:

Generally speaking, the protectionist system today is conservative, whereas the Free Trade system has a destructive effect. It destroys the former nationalities and renders the contrast between proletariat and bourgeois more acute. In a word, the Free Trade system is precipitating the social revolution. And only in this revolutionary sense do I vote for Free Trade.[27]

For Marx, capitalism was part of an inexorable dialectical process that, like the progressive-linear view of history, sees humanity ascending from primitive communism, through feudalism, capitalism, socialism, and ultimately – as the end of history – to a millennial world of Communism. Throughout this dialectical, progressive unfolding, the impelling force of history is class struggle for the primacy of sectional economic interests. In Marxian economic reductionism history is relegated to the struggle:

[The struggle between] freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed . . . in constant opposition to one another, carried on uninterrupted, now hidden, now open, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary re-constitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.[28]

Marx accurately describes the destruction of traditional society as intrinsic to capitalism, and goes on to describe what we today call “globalization.” Those who advocate free trade while calling themselves conservatives might like to consider why Marx supported free trade and described it as both “destructive” and as “revolutionary.” Marx saw it as the necessary ingredient of the dialectic process that is imposing universal standardization; this is likewise precisely the aim of Communism.

Marx accurately describes the destruction of traditional society as intrinsic to capitalism, and goes on to describe what we today call “globalization.” Those who advocate free trade while calling themselves conservatives might like to consider why Marx supported free trade and described it as both “destructive” and as “revolutionary.” Marx saw it as the necessary ingredient of the dialectic process that is imposing universal standardization; this is likewise precisely the aim of Communism.

In describing the dialectical role of capitalism, Marx states that wherever the “bourgeoisie” “has got the upper hand [he] has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations.” The bourgeoisie or what we might call the merchant class – which is accorded a subordinate position in traditional societies, but assumes superiority under “modernism” – “has pitilessly torn asunder” feudal bonds, and “has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest,” and “callous cash payment.” It has, among other things, “drowned” religiosity and chivalry “in the icy water of egotistical calculation.” “It has resolved personal worth into exchange value, and in place of the numberless indefeasible chartered freedoms, has set up that single, unconscionable freedom – Free Trade.”[29] Where the conservative stands in opposition to the Marxian analysis of capitalism is in Marx’s regarding the process as both inexorable and desirable.

Marx condemned opposition to this dialectical process as “reactionary.” Marx was here defending Communists against claims by “reactionaries” that his system would result in the destruction of the traditional family, and relegate the professions to mere “wage-labor,” by stating that this was already being done by capitalism anyway and is therefore not a process that is to be resisted – which is “Reactionism” – but welcomed as a necessary phase leading to Communism.

Uniformity of Production & Culture

Marx saw the constant need for the revolutionizing of the instruments of production as inevitable under capitalism, and this in turn brought society into a continual state of flux, of “everlasting uncertainty and agitation,” which distinguishes the “bourgeoisie epoch from all other ones.”[30] The “need for a constantly expanding market” means that capitalism spreads globally, and thereby gives a “cosmopolitan character” to “modes of production and consumption in every country.” In Marxist dialectics, this is a necessary part of destroying national boundaries and distinctive cultures as a prelude to world socialism. It is capitalism that establishes the basis for internationalism. Therefore, when the Marxist rants against “globalization,” he does so as rhetoric in the pursuit of a political agenda; not from ethical opposition to globalization.

Marx identifies the opponents of this capitalist internationalizing process not as Marxists, but as “Reactionists.” The reactionaries are appalled that the old local and national industries are being destroyed, self-sufficiency is being undermined, and “we have . . . universal inter-dependence of nations.” Likewise in the cultural sphere, “national and local literatures” are displaced by “a world literature.”[31] The result is a global consumer culture. Ironically, while the US was the harbinger of internationalizing tendencies in the arts, at the very start of the Cold War the most vigorous opponents of this were the Stalinists, who called this “rootless cosmopolitanism.”[32] It is such factors that prompted Yockey to conclude that the US represented a purer form of Bolshevism – as a method of cultural destruction – than the USSR. It is also why the diehard core of international Marxism, especially the Trotskyites, ended up in the US camp during the Cold War and metamorphosed into “neo-conservatism,”[33] whose antithesis in the US is not the Left, but paleoconservatism. These post-Trotskyites have no business masquerading as “conservatives,” “new” or otherwise.

With this revolutionizing and standardization of the means of production comes a loss of meaning that comes from being part of a craft or a profession, or “calling.” Obsession with work becomes an end in itself, which fails to provide higher meaning because it has been reduced to that of a solely economic function. In relation to the ruin of the traditional order by the triumph of the “bourgeoisie,” Marx said that:

Owing to the extensive use of machinery and to division of labor, the work of the proletarians has lost all individual character, and, consequently, all charm for the workman. He becomes an appendage of the machine, and it is only the most simple, most monotonous, and the most easily acquired knack, that is required of him . . .[34]

Whereas the Classical corporations and the medieval guilds fulfilled a role that was metaphysical and cultural in terms of one’s profession, these have been replaced by the trade unions as nothing more than instruments of economic competition. The entirety of civilization has become an expression of money-values, but preoccupation with the Gross Domestic Product cannot be a substitute for more profound human values. Hence it is widely perceived that those among the wealthy are not necessarily those who are fulfilled, and the affluent often exist in a void, with an undefined yearning that might be filled with drugs, alcohol, divorce, and suicide. Material gain does not equate with what Jung called “individuation” or what humanistic psychology calls “self-actualization.” Indeed, the preoccupation with material accumulation, whether under capitalism or Marxism, enchains man to the lowest level of animalistic existence. Here the Biblical axiom is appropriate: “Man does not live by bread alone.”

The Megalopolis

Of particular interest is that Marx writes of the manner by which the rural basis of the traditional order succumbs to urbanization and industrialization; which is what formed the “proletariat,” the rootless mass that is upheld by socialism as the ideal rather than as a corrupt aberration. Traditional societies are literally rooted in the soil. Under capitalism, village life and localized life are, as Marx said, made passé by the city and mass production. Marx referred to the country being subjected to the “rule of the towns.”[35] It was a phenomenon – the rise of the city concomitant with the rise of the merchant – that Spengler states is a symptom of the decay of a civilization in its sterile phase, where money values rule.[36]

Marx writes that what has been created is “enormous cities”; what Spengler calls “Megalopolitanism.” Again, what distinguishes Marx from traditionalists in his analysis of capitalism is that he welcomes this destructive feature of capitalism. When Marx writes of urbanization and the alienation of the former peasantry and artisans by their proletarianization in the cities, thereby becoming cogs in the mass production process, he refers to this not as a process to be resisted, but as inexorable and as having “rescued a considerable part of the population from the idiocy of rural life.”[37]

“Reactionism”

Marx points out in The Communist Manifesto that “Reactionists” (sic) view with “great chagrin”[38] the dialectical processes of capitalism. The reactionary, or the “Rightist,” is the anti-capitalist par excellence, because he is above and beyond the zeitgeist from which both capitalism and Marxism emerged, and he rejects in total the economic reductionism on which both are founded. Thus the word “reactionary,” usually used in a derogatory sense, can be accepted by the conservative as an accurate term for what is required for a cultural renascence.

Marx condemned resistance to the dialectical process as “Reactionist”:

The lower middle class, the small manufacturer, the shopkeeper, the artisan, the peasant. All these fight against the bourgeoisie, to save from extinction their existence as fractions of the middle class. They are therefore not revolutionary, but conservative. Nay more, they are reactionary, for they try to roll back the wheel of history. If by chance they are revolutionary, they are so only in view of their impending transfer into the proletariat, they thus defend not their present, but their future interests, they desert their own standpoint to place themselves at that of the proletariat.[39]

This so-called “lower middle class” is therefore inexorably condemned to the purgatory of proletarian dispossession until such time as it recognizes its historical revolutionary class role, and “expropriates the expropriators.” This “lower middle class” can either emerge from purgatory by joining the ranks of the proletarian chosen people, become part of the socialist revolution, and enter a new millennium, or it can descend from its class purgatory, if it insists on trying to maintain the traditional order, and be consigned to oblivion, which might be hastened by the firing squads of Bolshevism.

Marx devotes Section Three of his Communist Manifesto to a repudiation of “reactionary socialism.” He condemns the “feudal socialism” that arose among the old remnants of the aristocracy, which had sought to join forces with the “working class” against the bourgeoisie. Marx states that the aristocracy, in trying to reassert their pre-bourgeois position, had actually lost sight of their own class interests in siding with the proletariat.[40] This is nonsense. An alliance of the dispossessed professions into what had become the so-called proletariat, with the increasingly dispossessed aristocracy, is an organic alliance which finds its enemies as much in Marxism as in capitalism. Marx raged against the budding alliance between the aristocracy and those dispossessed professions that resisted being proletarianized. Hence, Marx condemns “feudal socialism” as “half echo of the past, half menace of the future.”[41] It was a movement that enjoyed significant support among craftsmen, clergymen, nobles, and literati in Germany in 1848, who repudiated the free market that had divorced the individual from Church, State, and community, “and placed egoism and self-interest before subordination, commonality, and social solidarity.”[42] Max Beer, a historian of German socialism, stated of these “Reactionists,” as Marx called them:

The modern era seemed to them to be built on quicksands, to be chaos, anarchy, or an utterly unmoral and godless outburst of intellectual and economic forces, which must inevitably lead to acute social antagonism, to extremes of wealth and poverty, and to a universal upheaval. In this frame of mind, the Middle Ages, with its firm order in Church, economic and social life, its faith in God, its feudal tenures, its cloisters, its autonomous associations and its guilds appeared to these thinkers like a well-compacted building . . .[43]

It is just such an alliance of all classes – once vehemently condemned by Marx as “Reactionist” – that is required to resist the common subversive phenomena of free trade and revolution. If the Right wishes to restore the health of the cultural organism that is predicated on traditional values, then it cannot do so by embracing economic doctrines that are themselves antithetical to tradition, and which were welcomed by Marx as part of a subversive process.

This article is a somewhat different version of an article that originally appeared in the journal Anamnesis, “Marx Contra Marx [5].”

Notes

1. Oswald Spengler (1928), The Decline of The West (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1971).

2. Brooks Adams, The Law of Civilisation and Decay: An Essay on History [6] (London: Macmillan & Co., 1896).

3. Francis Parker Yockey, Imperium [7] (Sausalito, California: The Noontide Press, 1969).

4. Eric Bentley, The Cult of the Superman: A Study of the Idea of Heroism in Carlyle & Nietzsche [8](London: Robert Hale Ltd., 1947).

5. Francis Parker Yockey, op. cit., p. 80.

6. Karl Marx (1873), Capital, “Afterword” (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1970), Vol. 1, p. 29.

7. G. W. F. Hegel (1837), The Philosophy of History [9], “Introduction: The Course of the World’s History[10].”

8. The Cromwellian Revolution.

9. Anthony Ludovici, A Defence of Conservatism [11] (1927), Chapter 3, “Conservatism in Practice.”

10. Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Asceticism and the Spirit of Capitalism[12] (London: Unwin Hyman, 1930).

11. R. D. Meade & W. C. Davis, Judah P. Benjamin: Confederate Statesman [13] (Louisiana State University Press, 2001), p. 270.

12. Oswald Spengler (1919), Prussian and Socialism (Paraparaumu, New Zealand: Renaissance Press, 2005), p. 4.

13. Oswald Spengler, The Decline of The West, op. cit., Vol. 2, p. 506.

14. Francis Parker Yockey, op. cit., p. 81.

15. Francis Parker Yockey, ibid., p. 84.

16. Oswald Spengler, op. cit. The tables of “contemporary” cultural, spiritual and political epochs in The Decline can be found online here [14].

17. The only aspect more widely recalled today being the “divine right of Kings.”

18. Julius Evola, Revolt against the Modern World [15] (Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions international, 1995), p. 105.

19. Julius Evola, , ibid., p. 106.

20. Francis Parker Yockey, op. cit., p. 84.

21. Asa Briggs (ed.), The Nineteenth Century: The Contradictions of Progress [16] (New York: Bonanza Books, 1985), p. 29.

22. Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer:

Things fall apart, the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world . . . W. B. Yeats, “The Second Coming [17],” 1921.

23. Oswald Spengler, The Hour of Decision [18] (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1934), pp. 42-43.

24. Oswald Spengler, The Decline of The West, op. cit., Vol. 2, p. 464.

25. Oswald Spengler, ibid. p. 402.

26. K. R. Bolton, Revolution from Above [19] (London: Arktos, 2011).

27. Oswald Spengler, The Hour of Decision, op. cit., p. 141; citing Marx, Appendix to Elend der Philosophie, 1847.

28. Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1975), p. 41.

29. Karl Marx, ibid., p. 44.

30. Karl Marx, ibid., p. 47.

31. Karl Marx, ibid., pp. 46-47.

32. F. Chernov, “Bourgeois Cosmopolitanism and Its Reactionary Role [20],” Bolshevik: Theoretical and Political Magazine of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) ACP(B), Issue #5, 15 March 1949, pp. 30-41.

33. K. R. Bolton, “America’s ‘World Revolution’: Neo-Trotskyist Foundations of U.S. Foreign Policy [21],” Foreign Policy Journal, May 3, 2010.

34. Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto, op. cit., p. 51.

35. Karl Marx, ibid., p. 47.

36. Oswald Spengler, The Decline of The West, op. cit., Vol. 2, Chapter 4, (a) “The Soul of the City,” pp. 87-110.

37. Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto, op. cit., p. 47.

38. Karl Marx, ibid, p. 46.

39. Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto, ibid., 57.

40. Karl Marx, ibid., III “Socialist and Communist Literature, 1. Reactionary Socialism, a. Feudal Socialism,” p. 77.

41. Karl Marx, ibid., p. 78.

42. Max Beer, A General History of Socialism and Social Struggle [22] (New York: Russell and Russell, 1957), Vol. 2, p. 109.

43. Max Beer, ibid., pp. 88-89.

Related

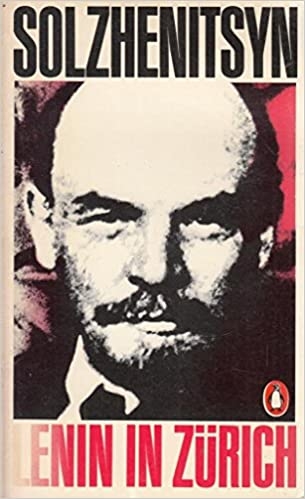

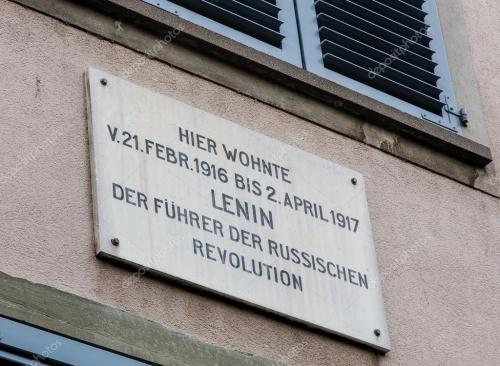

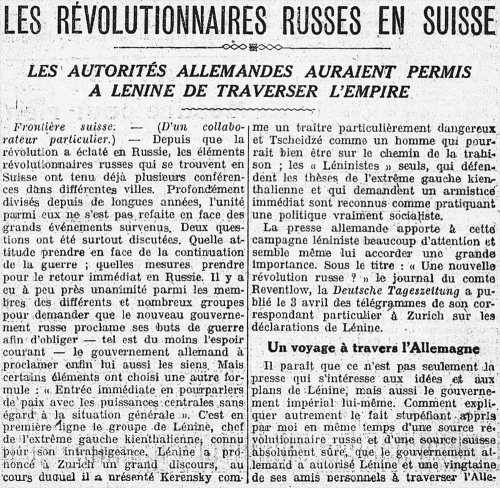

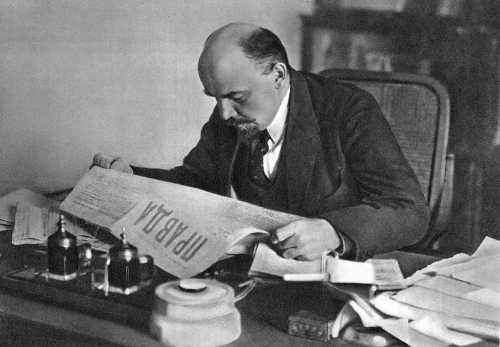

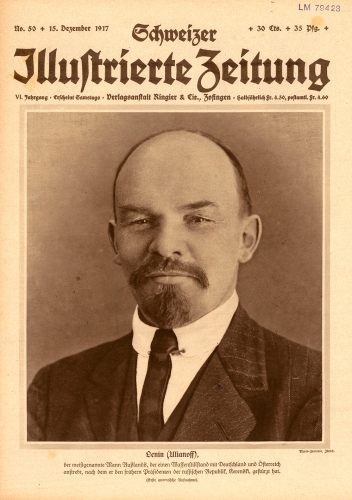

In 1975, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn excised the several Lenin chapters from his massive and unfinished Red Wheel epic and compiled them into one volume entitled Lenin in Zürich. At the time, only one of these chapters had been published — in Knot I of the Red Wheel, known as August 1914 — while the remaining chapters would still have to languish in the author’s desk drawer for decades before appearing as part of The Red Wheel proper (November 1916 and March 1917, specifically). In order to save time and make an impression on his contemporaries, many of whom in the West still harbored misplaced sympathies for Lenin, Solzhenitsyn decided to share with the world his eye-opening and unforgettable treatment of the Soviet Revolutionary.

In 1975, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn excised the several Lenin chapters from his massive and unfinished Red Wheel epic and compiled them into one volume entitled Lenin in Zürich. At the time, only one of these chapters had been published — in Knot I of the Red Wheel, known as August 1914 — while the remaining chapters would still have to languish in the author’s desk drawer for decades before appearing as part of The Red Wheel proper (November 1916 and March 1917, specifically). In order to save time and make an impression on his contemporaries, many of whom in the West still harbored misplaced sympathies for Lenin, Solzhenitsyn decided to share with the world his eye-opening and unforgettable treatment of the Soviet Revolutionary.

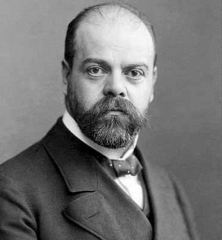

A man known as Parvus appears foremost among the Jews in Lenin in Zürich. Born Izrail Lazarevich Gelfand, he comes across, at least to Lenin, as an enigmatic and somewhat unscrupulous capitalist and millionaire who, for some reason, dedicates his life to socialist causes. Either this, or he wishes to destroy Russia while exhibiting a suspicious allegiance to Germany. Parvus, along with his protégé Leon Trotsky, had tried and failed to overthrow the Tsar in 1905, and now offers a new plan: With his deep contacts in the German government, he will arrange for the Bolsheviks’ to travel through Germany in order to re-enter Russia where they can foment revolution against a weakened Tsar. This would serve not only Lenin but Parvus’ German friends as well by knocking Russia out of the war. Suspicious of Parvus’ outsider status, and especially of his tolerance of Lenin’s detested Mensheviks, Lenin at first refuses. However, he cannot shake his respect and fascination for this mysterious benefactor.

A man known as Parvus appears foremost among the Jews in Lenin in Zürich. Born Izrail Lazarevich Gelfand, he comes across, at least to Lenin, as an enigmatic and somewhat unscrupulous capitalist and millionaire who, for some reason, dedicates his life to socialist causes. Either this, or he wishes to destroy Russia while exhibiting a suspicious allegiance to Germany. Parvus, along with his protégé Leon Trotsky, had tried and failed to overthrow the Tsar in 1905, and now offers a new plan: With his deep contacts in the German government, he will arrange for the Bolsheviks’ to travel through Germany in order to re-enter Russia where they can foment revolution against a weakened Tsar. This would serve not only Lenin but Parvus’ German friends as well by knocking Russia out of the war. Suspicious of Parvus’ outsider status, and especially of his tolerance of Lenin’s detested Mensheviks, Lenin at first refuses. However, he cannot shake his respect and fascination for this mysterious benefactor. Another Jew who figures prominently in Lenin in Zürich is Radek (born Karl Berngardovich Sobelsohn). Lenin has tremendous respect for Radek as a writer and propagandist — that Radek had become one of the Soviet Union’s most prominent journalists years after Lenin’s death certainly justifies Lenin’s esteem. In all, he is clever and resourceful and the only person to whom Lenin would voluntarily surrender his pen. After the February Revolution in Russia, as Lenin prepares for travel back to his home country according to Parvus’ plan, Radek contrives ingenious solutions to formidable logistical problems that threaten to sink the enterprise. This makes Lenin, for one of the few times in the book, truly happy.

Another Jew who figures prominently in Lenin in Zürich is Radek (born Karl Berngardovich Sobelsohn). Lenin has tremendous respect for Radek as a writer and propagandist — that Radek had become one of the Soviet Union’s most prominent journalists years after Lenin’s death certainly justifies Lenin’s esteem. In all, he is clever and resourceful and the only person to whom Lenin would voluntarily surrender his pen. After the February Revolution in Russia, as Lenin prepares for travel back to his home country according to Parvus’ plan, Radek contrives ingenious solutions to formidable logistical problems that threaten to sink the enterprise. This makes Lenin, for one of the few times in the book, truly happy.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

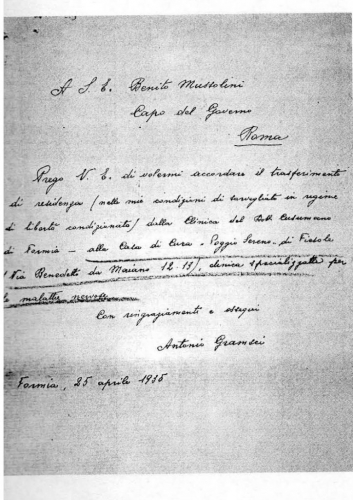

Antonio Gramsci revendique pour le groupe communiste de l'"Ordine Nuovo" (qu'il a fondé en 1919 avec Palmiro Togliatti et d'autres) le mérite d'avoir prôné une "forme d'"américanisme" acceptable pour les masses ouvrières". Pour Gramsci, il existe en fait un "ennemi principal" qui est la "tradition", "la civilisation européenne (...), la vieille et anachronique structure sociale démographique européenne" [10]. Nous devons donc remercier, dit-il, la "vieille classe ploutocratique", parce qu'elle a essayé d'introduire "une forme très moderne de production et de travail telle qu'offerte par le type américain le plus perfectionné, l'industrie d'Henry Ford" [11].

Antonio Gramsci revendique pour le groupe communiste de l'"Ordine Nuovo" (qu'il a fondé en 1919 avec Palmiro Togliatti et d'autres) le mérite d'avoir prôné une "forme d'"américanisme" acceptable pour les masses ouvrières". Pour Gramsci, il existe en fait un "ennemi principal" qui est la "tradition", "la civilisation européenne (...), la vieille et anachronique structure sociale démographique européenne" [10]. Nous devons donc remercier, dit-il, la "vieille classe ploutocratique", parce qu'elle a essayé d'introduire "une forme très moderne de production et de travail telle qu'offerte par le type américain le plus perfectionné, l'industrie d'Henry Ford" [11].

Nous avons parlé plus tôt de la littérature américaine. Eh bien, l'une des manifestations les plus significatives de la culture antifasciste qui a eu lieu pendant le Ventennio de Mussolini a été la publication de l'anthologie Americana éditée par Elio Vittorini pour l'éditeur Bompiani en 1942 (et toujours réédité depuis).

Nous avons parlé plus tôt de la littérature américaine. Eh bien, l'une des manifestations les plus significatives de la culture antifasciste qui a eu lieu pendant le Ventennio de Mussolini a été la publication de l'anthologie Americana éditée par Elio Vittorini pour l'éditeur Bompiani en 1942 (et toujours réédité depuis).

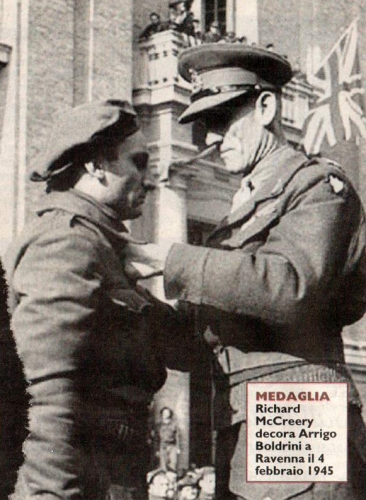

Dans le Nord, depuis février 1943, le Parti communiste, le Parti d'action, le Parti prolétarien pour une République socialiste et le Parti socialiste chrétien étaient en contact avec l'OSS, les services secrets américains, par l'intermédiaire d'un agent de liaison de premier ordre: l'ingénieur Adriano Olivetti (photo), un ami de Carlo Rosselli [26].

Dans le Nord, depuis février 1943, le Parti communiste, le Parti d'action, le Parti prolétarien pour une République socialiste et le Parti socialiste chrétien étaient en contact avec l'OSS, les services secrets américains, par l'intermédiaire d'un agent de liaison de premier ordre: l'ingénieur Adriano Olivetti (photo), un ami de Carlo Rosselli [26].

En 1944, devant le spectacle d'une extrême gauche à la solde des Anglo-Américains, le fasciste républicain Stanis Ruinas (photo) s'adresse à l'un de ses vieux amis, passé du fascisme anti-bourgeois au communisme, en ces termes : "Au risque de passer pour un naïf, j'avoue ne pas comprendre comment des hommes qui se proclament révolutionnaires - socialistes communistes anarchistes - et qui, pour leurs idéaux, ont subi la prison et l'exil, peuvent applaudir l'Angleterre ploutocratique et l'Amérique trustiste qui, au nom de la démocratie et de la liberté démocratique, dévastent l'Europe. J'anticipe votre réponse. En tant que révolutionnaire, vous n'aimez pas Hitler et vous ne faites pas confiance à Mussolini. Et c'est très bien. Mais comment pouvez-vous faire confiance à l'Angleterre impérialiste qui a trahi la Perse, écrasé les républiques boers, opprimé l'Inde et l'Égypte pendant si longtemps, et qui s'arroge le droit de protéger et de diriger tant de peuples dignes de liberté ? (...) Comment pouvez-vous concilier vos idéaux révolutionnaires avec ceux de Churchill et de Roosevelt ?" [32].

En 1944, devant le spectacle d'une extrême gauche à la solde des Anglo-Américains, le fasciste républicain Stanis Ruinas (photo) s'adresse à l'un de ses vieux amis, passé du fascisme anti-bourgeois au communisme, en ces termes : "Au risque de passer pour un naïf, j'avoue ne pas comprendre comment des hommes qui se proclament révolutionnaires - socialistes communistes anarchistes - et qui, pour leurs idéaux, ont subi la prison et l'exil, peuvent applaudir l'Angleterre ploutocratique et l'Amérique trustiste qui, au nom de la démocratie et de la liberté démocratique, dévastent l'Europe. J'anticipe votre réponse. En tant que révolutionnaire, vous n'aimez pas Hitler et vous ne faites pas confiance à Mussolini. Et c'est très bien. Mais comment pouvez-vous faire confiance à l'Angleterre impérialiste qui a trahi la Perse, écrasé les républiques boers, opprimé l'Inde et l'Égypte pendant si longtemps, et qui s'arroge le droit de protéger et de diriger tant de peuples dignes de liberté ? (...) Comment pouvez-vous concilier vos idéaux révolutionnaires avec ceux de Churchill et de Roosevelt ?" [32].

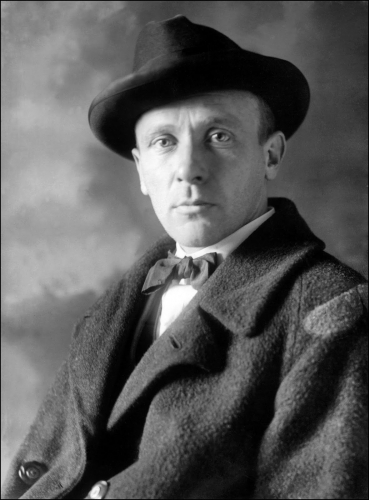

Wie mijn boekbesprekingen volgt, zal zich misschien herinneren dat ik er eind augustus 2019 (het lijkt alweer een eeuwigheid geleden) een publiceerde over een ander werk van

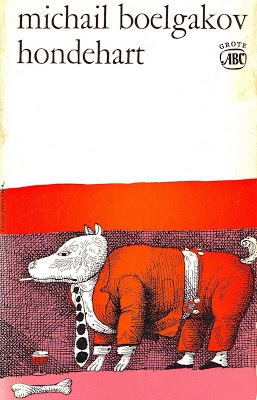

Wie mijn boekbesprekingen volgt, zal zich misschien herinneren dat ik er eind augustus 2019 (het lijkt alweer een eeuwigheid geleden) een publiceerde over een ander werk van  Zo, om de clue te weten te komen, moet u het boekje al niet meer lezen, maar u zal allicht ook niet meer opkijken van het feit dat dit werk in de Sovjet-Unie niet mocht gepubliceerd worden (helaas dook het in het Westen ook pas op toen hij al overleden was, net zoals De Meester en Margarita trouwens). Een duidelijker kritiek op het idee van de maakbare mens is nauwelijks denkbaar. En daarmee vormt het boek eigenlijk net zo goed een aanklacht tegen het nationaal-socialisme of tegen volstrekt waanzinnige moderne vormen van utopieën genre de veelbesproken Great Reset. Je kan de mens wel uit het vuilnis halen, maar niet het vuilnis uit de mens. Je kan de mens proberen aan te passen aan je communistische, nationaal-socialistische, post-modernistische ideetjes, maar de mens zal altijd een mens blijven en zelfs als er geen externe factoren meespelen – iets waar mensen als Klaus Schwab vurig naar streven door de hele wereld mee te slepen in hun waanzin –, zal je utopie aan dat simpele feit ten onder gaan.

Zo, om de clue te weten te komen, moet u het boekje al niet meer lezen, maar u zal allicht ook niet meer opkijken van het feit dat dit werk in de Sovjet-Unie niet mocht gepubliceerd worden (helaas dook het in het Westen ook pas op toen hij al overleden was, net zoals De Meester en Margarita trouwens). Een duidelijker kritiek op het idee van de maakbare mens is nauwelijks denkbaar. En daarmee vormt het boek eigenlijk net zo goed een aanklacht tegen het nationaal-socialisme of tegen volstrekt waanzinnige moderne vormen van utopieën genre de veelbesproken Great Reset. Je kan de mens wel uit het vuilnis halen, maar niet het vuilnis uit de mens. Je kan de mens proberen aan te passen aan je communistische, nationaal-socialistische, post-modernistische ideetjes, maar de mens zal altijd een mens blijven en zelfs als er geen externe factoren meespelen – iets waar mensen als Klaus Schwab vurig naar streven door de hele wereld mee te slepen in hun waanzin –, zal je utopie aan dat simpele feit ten onder gaan. Gevolgd door een hoofdstuk waarin het beest de operatiekamer ingelokt wordt en de chirurg er behalve wat worst ook een stukje filosofie tegenaan gooit als hij door zijn assistent gevraagd wordt hoe hij de hond heeft meegekregen: “Kwestie van aanhalen. Dat is de enige manier waarop je wat bereikt bij levende wezens. Met terreur kom je nergens, ongeacht het ontwikkelingspeil van een dier.” Waarna dat dier ook te weten komt dat hij dan wel nieuwe testikels heeft gekregen, maar ook ontmand is: “‘Pas op, jij, of ik maak je af! Weest u maar niet bang, hij bijt niet.’ ‘Bijt ik niet?’ vroeg de hond zich verbaasd af.” En waarin we kennis maken met het “huisbestuur”, de club van communistische zeloten die ervoor moeten zorgen dat Preobrazjenski datgene doet wat ook in

Gevolgd door een hoofdstuk waarin het beest de operatiekamer ingelokt wordt en de chirurg er behalve wat worst ook een stukje filosofie tegenaan gooit als hij door zijn assistent gevraagd wordt hoe hij de hond heeft meegekregen: “Kwestie van aanhalen. Dat is de enige manier waarop je wat bereikt bij levende wezens. Met terreur kom je nergens, ongeacht het ontwikkelingspeil van een dier.” Waarna dat dier ook te weten komt dat hij dan wel nieuwe testikels heeft gekregen, maar ook ontmand is: “‘Pas op, jij, of ik maak je af! Weest u maar niet bang, hij bijt niet.’ ‘Bijt ik niet?’ vroeg de hond zich verbaasd af.” En waarin we kennis maken met het “huisbestuur”, de club van communistische zeloten die ervoor moeten zorgen dat Preobrazjenski datgene doet wat ook in  Soit, verder naar het volgende hoofdstuk. Daarin begint de langzame transformatie van hond tot mens (of van mens tot de nationaal-socialistische versie van Nietzsches Übermensch, of van koelak tot communist) en leert het beest dat het goed is geketend te zijn. Liever een dikke hond aan de ketting dan een magere wolf in het bos. “De volgende dag kreeg de hond een brede, glimmende halsband om. Toen hij zich in de spiegel bekeek, was hij het eerste moment knap uit zijn humeur. Met de staart tussen de poten trok hij zich in de badkamer terug, zich afvragend hoe hij het ding zou kunnen doorschuren tegen een kist of een hutkoffer. Maar algauw drong het tot hem door dat hij gewoon een idioot was. Zina nam hem aan de lijn mee uit wandelen door de Oboechovlaan. De hond liep erbij als een arrestant en brandde van schaamte. Maar eenmaal voorbij de Christuskerk op de Pretsjistenka was hij er al helemaal achter wat een halsband in dit leven betekent. Bezeten afgunst stond te lezen in de ogen van alle honden die hij tegen kwam en ter hoogte van het Dodenpad blafte een uit zijn krachten gegroeide straatkeffer hem uit voor ‘rijkeluisflikker’ en ‘zespoot’. Toen zij de tramrails overhuppelden keek een agent van milietsie tevreden en met respect naar de halsband (…) Zo’n halsband is net een aktentas, grapte de hond in gedachte en wiebelend met zijn achterwerk schreed hij op naar de bel-etage als een heer van stand.” Of, zoals het in het volgende hoofdstuk al heet: “Maak je zelf maar niets wijs, jij zoekt heus de vrijheid niet meer op, treurde de hond snuivend. Die ben je ontwend. Ik ben een voornaam hondedier, een intelligent wezen, ik heb een beter bestaan leren kennen. En wat is de vrijheid helemaal? Rook, een fictie, een drogbeeld, anders niet … Een koortsdroom van die rampzalige democraten …”

Soit, verder naar het volgende hoofdstuk. Daarin begint de langzame transformatie van hond tot mens (of van mens tot de nationaal-socialistische versie van Nietzsches Übermensch, of van koelak tot communist) en leert het beest dat het goed is geketend te zijn. Liever een dikke hond aan de ketting dan een magere wolf in het bos. “De volgende dag kreeg de hond een brede, glimmende halsband om. Toen hij zich in de spiegel bekeek, was hij het eerste moment knap uit zijn humeur. Met de staart tussen de poten trok hij zich in de badkamer terug, zich afvragend hoe hij het ding zou kunnen doorschuren tegen een kist of een hutkoffer. Maar algauw drong het tot hem door dat hij gewoon een idioot was. Zina nam hem aan de lijn mee uit wandelen door de Oboechovlaan. De hond liep erbij als een arrestant en brandde van schaamte. Maar eenmaal voorbij de Christuskerk op de Pretsjistenka was hij er al helemaal achter wat een halsband in dit leven betekent. Bezeten afgunst stond te lezen in de ogen van alle honden die hij tegen kwam en ter hoogte van het Dodenpad blafte een uit zijn krachten gegroeide straatkeffer hem uit voor ‘rijkeluisflikker’ en ‘zespoot’. Toen zij de tramrails overhuppelden keek een agent van milietsie tevreden en met respect naar de halsband (…) Zo’n halsband is net een aktentas, grapte de hond in gedachte en wiebelend met zijn achterwerk schreed hij op naar de bel-etage als een heer van stand.” Of, zoals het in het volgende hoofdstuk al heet: “Maak je zelf maar niets wijs, jij zoekt heus de vrijheid niet meer op, treurde de hond snuivend. Die ben je ontwend. Ik ben een voornaam hondedier, een intelligent wezen, ik heb een beter bestaan leren kennen. En wat is de vrijheid helemaal? Rook, een fictie, een drogbeeld, anders niet … Een koortsdroom van die rampzalige democraten …”

Like the French Revolution, the Russian is also marked by an alliance of philosophy with fanatical enthusiasm. And this fanaticism of the Lenin cult has found its intellectual fans up into the present—one thinks of the hypersensitive aesthetician Walter Benjamin, of the communist model poet Bert Brecht, of the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, then the student movement of ’68 and the present-day left. We owe the most extreme formulation of the cult to Ernst Bloch: “Ubi Lenin, ibi Jerusalem,” where Lenin is, there is salvation, the kingdom of freedom and eternal childhood in God. Ernst Nolte was thus right when he characterized Marxism as “the last faith in Europe.” And this faith was “organized” by Lenin.

Like the French Revolution, the Russian is also marked by an alliance of philosophy with fanatical enthusiasm. And this fanaticism of the Lenin cult has found its intellectual fans up into the present—one thinks of the hypersensitive aesthetician Walter Benjamin, of the communist model poet Bert Brecht, of the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, then the student movement of ’68 and the present-day left. We owe the most extreme formulation of the cult to Ernst Bloch: “Ubi Lenin, ibi Jerusalem,” where Lenin is, there is salvation, the kingdom of freedom and eternal childhood in God. Ernst Nolte was thus right when he characterized Marxism as “the last faith in Europe.” And this faith was “organized” by Lenin.

The self-incriminations before the tribunals, which were not forced by torture, but also those in numerous writings of communist intellectuals, belong to the great moral scandals of history. One understands them better when one sees how Bolshevism abrogated the moral verities of bourgeois society. Lukács spoke of a “second ethics” that would forcibly and cruelly create clarity in the confused world of the humane. The terrorist is the Gnostic of the deed, who takes crime upon himself as a necessity in the struggle against capitalism. Lukács dedicated his essay “Tactics and Ethics” to the young generation of the Communist Party: the terrorist as hero sacrifices his ego on the altar of the idea that presents itself as an order issued from the world historical situation. And in a letter to Paul Ernst from May 4, 1915, one reads about the revolutionary: “Here—to save the soul—the soul itself must be sacrificed: one must, out of a mystical ethics, become a cruel political realist.” Such is in keeping with the syndrome that Manès Sperber called treason out of loyalty, that is, denial of one’s own standards and convictions, intellectual masochism, and obsequious ingratiation with the “working class.”

The self-incriminations before the tribunals, which were not forced by torture, but also those in numerous writings of communist intellectuals, belong to the great moral scandals of history. One understands them better when one sees how Bolshevism abrogated the moral verities of bourgeois society. Lukács spoke of a “second ethics” that would forcibly and cruelly create clarity in the confused world of the humane. The terrorist is the Gnostic of the deed, who takes crime upon himself as a necessity in the struggle against capitalism. Lukács dedicated his essay “Tactics and Ethics” to the young generation of the Communist Party: the terrorist as hero sacrifices his ego on the altar of the idea that presents itself as an order issued from the world historical situation. And in a letter to Paul Ernst from May 4, 1915, one reads about the revolutionary: “Here—to save the soul—the soul itself must be sacrificed: one must, out of a mystical ethics, become a cruel political realist.” Such is in keeping with the syndrome that Manès Sperber called treason out of loyalty, that is, denial of one’s own standards and convictions, intellectual masochism, and obsequious ingratiation with the “working class.”

En 1938 a un año de terminar la Guerra Civil española, el coronel del KGB Leonid Eitingon, empezó a formar con su colaboradora Caridad del Río Mercader (foto), comunista catalana y madre de Ramón Mercader del Río, un equipo de asesinos controlados por el Trust o sección exterior de la inteligencia soviética.

En 1938 a un año de terminar la Guerra Civil española, el coronel del KGB Leonid Eitingon, empezó a formar con su colaboradora Caridad del Río Mercader (foto), comunista catalana y madre de Ramón Mercader del Río, un equipo de asesinos controlados por el Trust o sección exterior de la inteligencia soviética.

En realidad fue Roberto Sheldon Harte, que era uno de los infieles pistoleros de Trotski, un recién llegado que había sido reclutado en Nueva York por el dirigente del grupo sionista Socialist Workers Party, Joseph Hansen, a quien el portal World Socialist Web Site puso en evidencia como agente del FBI, lo mismo que a su esposa Rebeca.

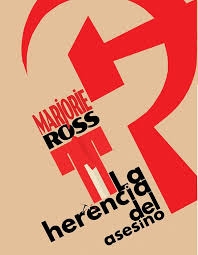

En realidad fue Roberto Sheldon Harte, que era uno de los infieles pistoleros de Trotski, un recién llegado que había sido reclutado en Nueva York por el dirigente del grupo sionista Socialist Workers Party, Joseph Hansen, a quien el portal World Socialist Web Site puso en evidencia como agente del FBI, lo mismo que a su esposa Rebeca. El libro de la destacada escritora costarricense Marjorie Ross, mencionado en este subtítulo, tiene de todo, incluidas las respuestas cruciales a las preguntas que se hicieron en todos los países los enterados de las discrepancias entre los dos beneficiarios eventuales de cara al poder que dejaría vacante Lenin al morir y que fueron mencionados en su “testamento”. Lenin destacó la inclinación de Trotski por el aspecto administrativo de los asuntos, y de Stalin su deslealtad y su poca delicadeza en el tratamiento de sus camaradas.

El libro de la destacada escritora costarricense Marjorie Ross, mencionado en este subtítulo, tiene de todo, incluidas las respuestas cruciales a las preguntas que se hicieron en todos los países los enterados de las discrepancias entre los dos beneficiarios eventuales de cara al poder que dejaría vacante Lenin al morir y que fueron mencionados en su “testamento”. Lenin destacó la inclinación de Trotski por el aspecto administrativo de los asuntos, y de Stalin su deslealtad y su poca delicadeza en el tratamiento de sus camaradas.

Much of this confusion stems from the fact that National Bolshevism did not have a guiding text or any kind of magnum opus for the proliferation of a workers’ state ruled by nationalist sentiment. The closest to such a founding document is Ernst Junger’s

Much of this confusion stems from the fact that National Bolshevism did not have a guiding text or any kind of magnum opus for the proliferation of a workers’ state ruled by nationalist sentiment. The closest to such a founding document is Ernst Junger’s  Niekisch would become the greatest propagandist for National Bolshevism during the Weimar era. His short-lived journal Widerstand would publish Junger and other German writers who wanted to mix the austere radicalism of the Bolsheviks with that frontline soldier’s dedication to nation.

Niekisch would become the greatest propagandist for National Bolshevism during the Weimar era. His short-lived journal Widerstand would publish Junger and other German writers who wanted to mix the austere radicalism of the Bolsheviks with that frontline soldier’s dedication to nation.

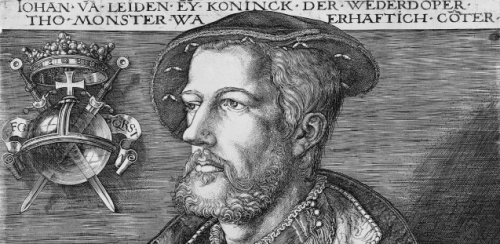

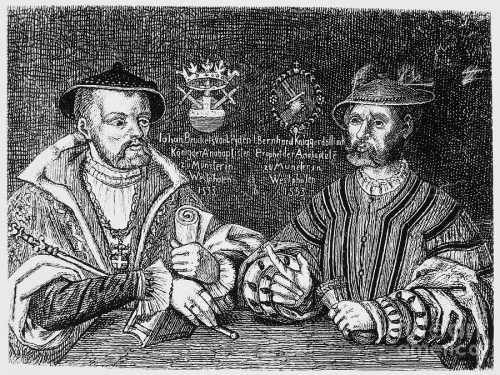

The poor hapless people of Münster were now doomed totally. The bishop kept firing leaflets into the town promising a general amnesty if the people would only revolt and depose King Bockelson and his court and hand them over. To guard against such a threat, Bockelson stepped up his reign of terror still further. In early May, he divided the town into 12 sections, and placed a “duke” over each one with an armed force of 24 men. The dukes were foreigners like himself; as Dutch immigrants they were likely to be loyal to Bockelson. Each duke was strictly forbidden to leave his section, and the dukes, in turn, prohibited any meetings whatsoever of even a few people. No one was allowed to leave town, and any caught plotting to leave, helping anyone else to leave, or criticizing the king, was instantly beheaded, usually by King Bockelson himself. By mid-June such deeds were occurring daily, with the body often quartered and nailed up as a warning to the masses.

The poor hapless people of Münster were now doomed totally. The bishop kept firing leaflets into the town promising a general amnesty if the people would only revolt and depose King Bockelson and his court and hand them over. To guard against such a threat, Bockelson stepped up his reign of terror still further. In early May, he divided the town into 12 sections, and placed a “duke” over each one with an armed force of 24 men. The dukes were foreigners like himself; as Dutch immigrants they were likely to be loyal to Bockelson. Each duke was strictly forbidden to leave his section, and the dukes, in turn, prohibited any meetings whatsoever of even a few people. No one was allowed to leave town, and any caught plotting to leave, helping anyone else to leave, or criticizing the king, was instantly beheaded, usually by King Bockelson himself. By mid-June such deeds were occurring daily, with the body often quartered and nailed up as a warning to the masses.

Les raisons pour lesquelles ce système n’a pas pu donner une véritable alternative au capitalisme étatsunien me paraissent tenir au modèle même de développement choisi par l’URSS, de fait, le modèle étasunien plus que les modèles européens (cf. les reportages de Joseph Roth, Rüssiche Reisen), où tout en maintenant et déployant des coûts sociaux gigantesques que le système étasunien laisse à la philanthropie privée ou simplement abandonne à la débrouillardise, à souvent à la délinquance… A-t-on mesuré les coûts des vacances très largement subventionnées par les syndicats et donc les entreprises, les systèmes d’enseignement gratuits, la couverture médicales, peut-être médiocre en qualité) mais elle aussi quasi gratuite, comme la protection sociale, la culture, etc. Prenons un autre exemple : lors d’une interview donnée vers la fin de sa vie Tarkovski, le cinéaste soviétique, affirmait qu’il regrettait avoir émigré, car les conditions de travail qu’il avait trouvé en Occident (Suède et Italie) l’obligeaient à travailler rapidement, et donc sans le fignolage extrême qu’il affectionnait, en raison des problèmes de coût et de rentabilité, tandis qu’en URSS disait-il, on peut refaire une scène quarante fois sans que personne de la production ne vienne vous demande d’arrêter parce que c’est trop cher ! Ceci multiplié à l’échelle d’un empire (multiplication des établissements d’enseignement dans les républiques asiatiques, multiplication des institutions culturelles locales, cinéma arméniens, géorgiens, du Kazakhstan, Ouzbékistan), nous montre des coûts dont les États-Unis se dispensaient de supporter. De plus et ce n’est pas négligeable, à l’échelle de l’économie mondiale, les Soviétiques n’ont jamais eu la maîtrise d’une quelconque parcelle du commerce mondial en ce que la monnaie étalon de tous les échanges a toujours été le dollar, voire dans certaines zones européennes, le mark allemand, mais jamais le rouble même avec des alliés outre-mer de l’URSS comme autrefois l’Egypte, l’Ethiopie, l’Angola ; le rouble avait cours au sein du Comecon, et encore de très nombreux échanges s’y établissaient sur la base du troc… Certes, nul ne peut nier que deux raisons entravèrent la compétition avec les États-Unis, d’une part l’ampleur des destructions de la Russie d’Europe et de l’Ukraine pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, (on ne mesure pas ou l’on ne veut mesurer aujourd’hui l’ampleur de ces pertes) et le coût de la reconstruction dans un empire ayant refusé pour des raisons politiques le plan Marshall, à cela on rappellera à nouveau les coût du développement des armements afin de maintenir la puissance soviétique face aux États-Unis et, last but not least, une gabegie typiquement russe (longuement dénoncée par certains écrivains depuis le milieux du XIXe siècle) qui tient de son rapport conflictuel à la modernité que l’on retrouve dans les Balkans, voire en Hongrie et dans les Pays Baltes… gabegie qui était déjà là lors de la première modernisation de la Russie à la fin du XIXe et au début du XXe siècles…

Les raisons pour lesquelles ce système n’a pas pu donner une véritable alternative au capitalisme étatsunien me paraissent tenir au modèle même de développement choisi par l’URSS, de fait, le modèle étasunien plus que les modèles européens (cf. les reportages de Joseph Roth, Rüssiche Reisen), où tout en maintenant et déployant des coûts sociaux gigantesques que le système étasunien laisse à la philanthropie privée ou simplement abandonne à la débrouillardise, à souvent à la délinquance… A-t-on mesuré les coûts des vacances très largement subventionnées par les syndicats et donc les entreprises, les systèmes d’enseignement gratuits, la couverture médicales, peut-être médiocre en qualité) mais elle aussi quasi gratuite, comme la protection sociale, la culture, etc. Prenons un autre exemple : lors d’une interview donnée vers la fin de sa vie Tarkovski, le cinéaste soviétique, affirmait qu’il regrettait avoir émigré, car les conditions de travail qu’il avait trouvé en Occident (Suède et Italie) l’obligeaient à travailler rapidement, et donc sans le fignolage extrême qu’il affectionnait, en raison des problèmes de coût et de rentabilité, tandis qu’en URSS disait-il, on peut refaire une scène quarante fois sans que personne de la production ne vienne vous demande d’arrêter parce que c’est trop cher ! Ceci multiplié à l’échelle d’un empire (multiplication des établissements d’enseignement dans les républiques asiatiques, multiplication des institutions culturelles locales, cinéma arméniens, géorgiens, du Kazakhstan, Ouzbékistan), nous montre des coûts dont les États-Unis se dispensaient de supporter. De plus et ce n’est pas négligeable, à l’échelle de l’économie mondiale, les Soviétiques n’ont jamais eu la maîtrise d’une quelconque parcelle du commerce mondial en ce que la monnaie étalon de tous les échanges a toujours été le dollar, voire dans certaines zones européennes, le mark allemand, mais jamais le rouble même avec des alliés outre-mer de l’URSS comme autrefois l’Egypte, l’Ethiopie, l’Angola ; le rouble avait cours au sein du Comecon, et encore de très nombreux échanges s’y établissaient sur la base du troc… Certes, nul ne peut nier que deux raisons entravèrent la compétition avec les États-Unis, d’une part l’ampleur des destructions de la Russie d’Europe et de l’Ukraine pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, (on ne mesure pas ou l’on ne veut mesurer aujourd’hui l’ampleur de ces pertes) et le coût de la reconstruction dans un empire ayant refusé pour des raisons politiques le plan Marshall, à cela on rappellera à nouveau les coût du développement des armements afin de maintenir la puissance soviétique face aux États-Unis et, last but not least, une gabegie typiquement russe (longuement dénoncée par certains écrivains depuis le milieux du XIXe siècle) qui tient de son rapport conflictuel à la modernité que l’on retrouve dans les Balkans, voire en Hongrie et dans les Pays Baltes… gabegie qui était déjà là lors de la première modernisation de la Russie à la fin du XIXe et au début du XXe siècles…

Voici un ouvrage qui a le mérite d’amener à la fois des éléments novateurs pour déchiffrer l’énigme de la chute du Bloc soviétique et d’éclairer sur la situation actuelle des Pays de l’Est. Échappant à l’autoglorification des valeurs « démocratiques et libérales » qui est la règle de la plupart des analystes occidentaux sur le sujet, il présente une vision bien plus complexe de la réalité du système « socialiste ». Il donne aussi un tableau quasi complet de l’histoire économique et sociale immédiate des principales ex-républiques populaires.

Voici un ouvrage qui a le mérite d’amener à la fois des éléments novateurs pour déchiffrer l’énigme de la chute du Bloc soviétique et d’éclairer sur la situation actuelle des Pays de l’Est. Échappant à l’autoglorification des valeurs « démocratiques et libérales » qui est la règle de la plupart des analystes occidentaux sur le sujet, il présente une vision bien plus complexe de la réalité du système « socialiste ». Il donne aussi un tableau quasi complet de l’histoire économique et sociale immédiate des principales ex-républiques populaires.

In English-speaking states at least, there is a muddled dichotomy in regard to the Left and Right, particularly among media pundits and academics. What is often termed “New Right” or “Right” there is the reanimation of Whig-Liberalism. If the English wanted to rescue genuine conservatism from the free-trade aberration and return to their origins, they could do no better than to consult the early twentieth-century philosopher Anthony Ludovici, who succinctly defined the historical dichotomy rather than the commonality between Toryism and Whig-Liberalism, when discussing the health and vigor of the rural population in contrast to the urban:

In English-speaking states at least, there is a muddled dichotomy in regard to the Left and Right, particularly among media pundits and academics. What is often termed “New Right” or “Right” there is the reanimation of Whig-Liberalism. If the English wanted to rescue genuine conservatism from the free-trade aberration and return to their origins, they could do no better than to consult the early twentieth-century philosopher Anthony Ludovici, who succinctly defined the historical dichotomy rather than the commonality between Toryism and Whig-Liberalism, when discussing the health and vigor of the rural population in contrast to the urban: Spengler, one of the seminal philosopher-historians of the “Conservative Revolutionary” movement that arose in Germany in the aftermath of the First World War, was intrinsically anti-capitalist. He and others saw in capitalism and the rise of the bourgeoisie the agency of destruction of the foundations of traditional order, as did Marx. The essential difference is that the Marxists regarded it as part of a historical progression, whereas the revolutionary conservatives regarded it as a symptom of decline. Of course, since academe is dominated by mediocrity and cockeyed theories, this viewpoint is not widely understood in (mis)educated circles.

Spengler, one of the seminal philosopher-historians of the “Conservative Revolutionary” movement that arose in Germany in the aftermath of the First World War, was intrinsically anti-capitalist. He and others saw in capitalism and the rise of the bourgeoisie the agency of destruction of the foundations of traditional order, as did Marx. The essential difference is that the Marxists regarded it as part of a historical progression, whereas the revolutionary conservatives regarded it as a symptom of decline. Of course, since academe is dominated by mediocrity and cockeyed theories, this viewpoint is not widely understood in (mis)educated circles. Not only is our century superior to any that have gone before it but . . . it may be best compared with the whole preceding historical period. It must therefore be held to constitute the beginning of a new era of human progress. . . . We men of the 19th Century have not been slow to praise it. The wise and the foolish, the learned and the unlearned, the poet and the pressman, the rich and the poor, alike swell the chorus of admiration for the marvellous inventions and discoveries of our own age, and especially for those innumerable applications of science which now form part of our daily life, and which remind us every hour or our immense superiority over our comparatively ignorant forefathers.[21]

Not only is our century superior to any that have gone before it but . . . it may be best compared with the whole preceding historical period. It must therefore be held to constitute the beginning of a new era of human progress. . . . We men of the 19th Century have not been slow to praise it. The wise and the foolish, the learned and the unlearned, the poet and the pressman, the rich and the poor, alike swell the chorus of admiration for the marvellous inventions and discoveries of our own age, and especially for those innumerable applications of science which now form part of our daily life, and which remind us every hour or our immense superiority over our comparatively ignorant forefathers.[21] Marx accurately describes the destruction of traditional society as intrinsic to capitalism, and goes on to describe what we today call “globalization.” Those who advocate free trade while calling themselves conservatives might like to consider why Marx supported free trade and described it as both “destructive” and as “revolutionary.” Marx saw it as the necessary ingredient of the dialectic process that is imposing universal standardization; this is likewise precisely the aim of Communism.

Marx accurately describes the destruction of traditional society as intrinsic to capitalism, and goes on to describe what we today call “globalization.” Those who advocate free trade while calling themselves conservatives might like to consider why Marx supported free trade and described it as both “destructive” and as “revolutionary.” Marx saw it as the necessary ingredient of the dialectic process that is imposing universal standardization; this is likewise precisely the aim of Communism.

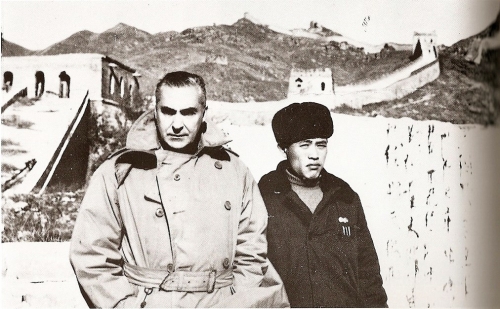

La implantación del comunismo en China en 1949, después de una prolongada guerra civil, en cuyo desenlace jugó un importante papel la incomprensión del problema por parte del gobierno de los Estados Unidos miembros de la Secretaría de Estado veían en Mao Tse tung, no un marxista leninista, sino a un «reformador agrario»-, supuso la realización de los experimentos sociales de consecuencias más desoladoras en la historia de la humanidad. Ante la magnitud de los datos que se conocen hoy, es muy posible que, en número de víctimas, se superase incluso las terribles cifras del estalinismo. Sobre dichas consecuencias trágicas existen numerosísimos testimonios no sólo de estudiosos occidentales, sino originales chinos.

La implantación del comunismo en China en 1949, después de una prolongada guerra civil, en cuyo desenlace jugó un importante papel la incomprensión del problema por parte del gobierno de los Estados Unidos miembros de la Secretaría de Estado veían en Mao Tse tung, no un marxista leninista, sino a un «reformador agrario»-, supuso la realización de los experimentos sociales de consecuencias más desoladoras en la historia de la humanidad. Ante la magnitud de los datos que se conocen hoy, es muy posible que, en número de víctimas, se superase incluso las terribles cifras del estalinismo. Sobre dichas consecuencias trágicas existen numerosísimos testimonios no sólo de estudiosos occidentales, sino originales chinos.

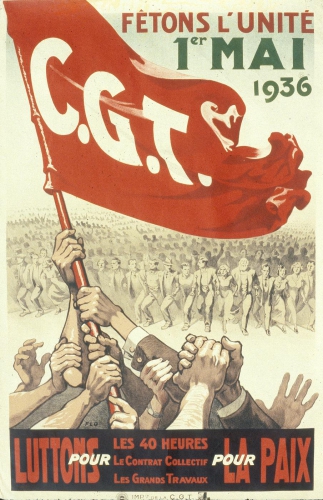

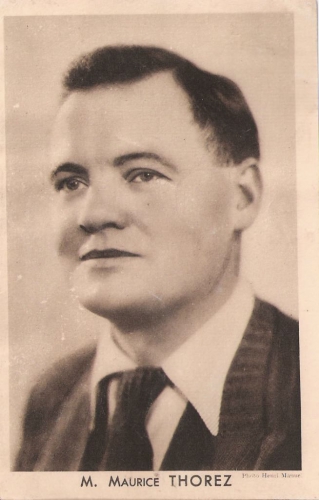

The initial response of the communists was indifferent. PCF leader Maurice Thorez stated that there was “ no difference between bourgeois democracy and fascism. They are two forms of capitalism . . . Between cholera and the plague one does not choose.” On the 7th of February, the PCF rejected a socialist overture to form a united front against what was widely perceived as a Fascist coup attempt.

The initial response of the communists was indifferent. PCF leader Maurice Thorez stated that there was “ no difference between bourgeois democracy and fascism. They are two forms of capitalism . . . Between cholera and the plague one does not choose.” On the 7th of February, the PCF rejected a socialist overture to form a united front against what was widely perceived as a Fascist coup attempt. Worker support for the People’s Front government was further eroded in 1937 following the rise of the fascist Parti Sociale Français (PSF). Following the fatal shootings of six workers by policemen in an anti-fascist demonstration at Clichy on March 16th, which lead to a call for a half-day strike in protest of the killings, Blum threatened to resign if the strike went ahead, and then failing to do so, ordered the police to crackdown on the workers who allegedly instigated the violence at Clichy.

Worker support for the People’s Front government was further eroded in 1937 following the rise of the fascist Parti Sociale Français (PSF). Following the fatal shootings of six workers by policemen in an anti-fascist demonstration at Clichy on March 16th, which lead to a call for a half-day strike in protest of the killings, Blum threatened to resign if the strike went ahead, and then failing to do so, ordered the police to crackdown on the workers who allegedly instigated the violence at Clichy.

El pasado día 23 de noviembre murió en la ciudad de Turín el filósofo italiano Costanzo Preve (nacido en Valenza en 1943). Filósofo marxista y profesor de historia y de filosofía de 1967 a 2002. Miembro del PCI de 1973 a 1975. En 1978 participó en la creación del Centro Studi di Materialismo Storico (CSMS).