“Socialism” is intrinsic to the “Right.” When journalists and academics refer in one breath to “liberalism, neoliberalism, and the Right-wing,” that attests to their ignorance, not to the accuracy of any such bastardization. Even at its most basic level of understanding, it seems to have been forgotten that in Britain there were Tories and Whigs in opposition. Now, Toryism has become so detached from its origins that there is indeed no distinction between British Conservativism, in the parliamentary sense at least, and Whig-liberalism. The same can be said for much of what is called often called “Right” across the world, but especially in the Anglophone states whose philosophy has been dominated by utilitarianism.

The “Right” has a rich but obscured legacy that revolts against capitalism. The “Right” is restorative, and arises when a culture-organism begins to decay. The works of Thomas Carlyle, an essay, Chartism (1840), and the book Past & Present (1843) could be the ideological basis of a true British Right, in which Carlyle condemns free trade from a conservative position. In these, he considered the supposed panacea of universal franchise and decried the debased state of the Aristocracy, which should be replaced with an “aristocracy of merit.” Carlyle stated that free trade would be a harbinger of “social revolution.” (When Karl Marx later said the same, he meant it, contrary to Carlyle, in a positive sense.) Carlyle condemned “Mammon,” materialism, and the “money nexus” of the bourgeoisie, and stated that the problems of the British were fundamentally spiritual and moral, from whence a repudiation of the money-ethos that dominated Britain should proceed. Carlyle did not write in the same stream as the British utilitarian philosophers from whom liberalism arose. He wrote in a more Occidental sense in repudiating the trade and commercial mentality that had long pervaded British thinking, politics, and foreign policy; bourgeois and Whig, as Spengler and Werner Sombart pointed out. Yockey classified Carlyle among the few British philosophers writing from an “organic” perspective of history.

The “Right” has a rich but obscured legacy that revolts against capitalism. The “Right” is restorative, and arises when a culture-organism begins to decay. The works of Thomas Carlyle, an essay, Chartism (1840), and the book Past & Present (1843) could be the ideological basis of a true British Right, in which Carlyle condemns free trade from a conservative position. In these, he considered the supposed panacea of universal franchise and decried the debased state of the Aristocracy, which should be replaced with an “aristocracy of merit.” Carlyle stated that free trade would be a harbinger of “social revolution.” (When Karl Marx later said the same, he meant it, contrary to Carlyle, in a positive sense.) Carlyle condemned “Mammon,” materialism, and the “money nexus” of the bourgeoisie, and stated that the problems of the British were fundamentally spiritual and moral, from whence a repudiation of the money-ethos that dominated Britain should proceed. Carlyle did not write in the same stream as the British utilitarian philosophers from whom liberalism arose. He wrote in a more Occidental sense in repudiating the trade and commercial mentality that had long pervaded British thinking, politics, and foreign policy; bourgeois and Whig, as Spengler and Werner Sombart pointed out. Yockey classified Carlyle among the few British philosophers writing from an “organic” perspective of history.

Marx, so far from repudiating that mentality, was intellectually in thrall to it, as Sombart and Spengler explained, and this identity of Marxism with British utilitarian and materialist philosophy resulted in a crisis of the Left during the close of the 19th century when socialist thinkers realized the inadequacy of Marx in truly rejecting capitalism and the bourgeois spirit.

Carlyle set the tone of his condemnation of capitalist Britain with the opening paragraph of Past & Present in a far more eloquent sense than that of Marx; although the Whigs masquerading as “conservatives” then and now regard such words as rabid socialism:

The condition of England, on which many pamphlets are now in the course of publication, and many thoughts unpublished are going on in every reflective head, is justly regarded as one of the most ominous, and withal one of the strangest, ever seen in this world. England is full of wealth, of multifarious produce, supply for human want in every kind; yet England is dying of inanition. With unabated bounty the land of England blooms and grows; waving with yellow harvests; thick-studded with workshops, industrial implements, with fifteen millions of workers, understood to be the strongest, the cunningest and the willingest our Earth ever had; these men are here; the work they have done, the fruit they have realized is here, abundant, exuberant on every hand of us: and behold, some baleful fiat as of Enchantment has gone forth, saying, “Touch it not, ye workers, ye master-workers, ye master-idlers; none of you can touch it, no man of you shall be the better for it; this is enchanted fruit!” On the poor workers such fiat falls first, in its rudest shape; but on the rich masterworkers too it falls; neither can the rich master-idlers, nor any richest or highest man escape, but all are like to be brought low with it, and made “poor” enough, in the money-sense or a far fataller one. [1] [1]

Previously, in his essay Chartism, Carlyle had appealed not to class war but to class unity among fellow Britons, high-born and low, pointing out that the ruling classes did not even realize there was a problem to be solved, much to their own danger:

Previously, in his essay Chartism, Carlyle had appealed not to class war but to class unity among fellow Britons, high-born and low, pointing out that the ruling classes did not even realize there was a problem to be solved, much to their own danger:

How an Aristocracy, in these present times and circumstances, could, if never so well disposed, set about governing the Under Class? What they should do; endeavor or attempt to do? That is even the question of questions: — the question which they have to solve; which it is our utmost function at present to tell them, lies there for solving, and must and will be solved.

Insoluble we cannot fancy it. One select class Society has furnished with wealth, intelligence, leisure, means outward and inward for governing; another huge class, furnished by Society with none of those things, declares that it must be governed: Negative stands fronting Positive; if Negative and Positive cannot unite, — it will be worse for both! Let the faculty and earnest constant effort of England combine round this matter; let it once be recognized as a vital matter. Innumerable things our Upper Classes and Lawgivers might ‘do;’ but the preliminary of all things, we must repeat, is to know that a thing must need be done.

Alas, in regard to so very many things. Laissez-faire ought partly to endeavor to cease! But in regard to poor Sanspotatoe [Irish] peasants, Trades-Union craftsmen. Chartist cotton-spinners, the time has come when it must either cease or a worse thing straightway begin, — a thing of tinder-boxes, vitriol-bottles, second-hand pistols, a visibly insupportable thing in the eyes of all. [2] [2]

In the early 20th century, Anthony Ludovici and others attempted to return the Tory Party to its origins, and his works, like those of Carlyle, remain as timeless foundations on which the Anglophone Right can return to its actual premises. The U.S. Right has its foundation in Federalism, the Hamiltonian concept of North American as a people-nation-state — as Yockey recognized — but often insists on looking to its opposite, the Jeffersonian-style Jacobinism that was enthralled by the French Revolution and would have thwarted the American states from ever becoming a nation.

Occidental Synthesis

The German economist Friedrich List, in contrast to the British philosophers, was condemning free trade from a conservative position at around the same time as Carlyle. He espoused autarchy, which he called the “national system.” This was anathema to Marx, who saw such ideologies as antithetical to the dialectical march toward communism.

List critiqued free trade precisely on the grounds that Marx praised it; for its materialism, class divisiveness, and national dissolution. List wrote in his magnum opus:

The system of the school suffers, as we have already shown in the preceding chapters, from three main defects: firstly, from boundless cosmopolitanism, which neither recognizes the principle of nationality, nor takes into consideration the satisfaction of its interests; secondly, from a dead materialism, which everywhere regards chiefly the mere exchangeable value of things without taking into consideration the mental and political, the present and the future interests, and the productive powers of the nation; thirdly, from a disorganizing particularism and individualism, which, ignoring the nature and character of social labor and the operation of the union of powers in their higher consequences, considers private industry only as it would develop itself under a state of free interchange with society (i.e. with the whole human race) were that race not divided into separate national societies.

Between each individual and entire humanity, however, stands THE NATION, with its special language and literature, with its peculiar origin and history, with its special manners and customs, laws and institutions, with the claims of all these for existence, independence, perfection, and continuance for the future, and with its separate territory; a society which, united by a thousand ties of mind and of interests, combines itself into one independent whole, which recognizes the law of right for and within itself, and in its united character is still opposed to other societies of a similar kind in their national liberty, and consequently can only under the existing conditions of the world maintain self-existence and independence by its own power and resources. As the individual chiefly obtains by means of the nation and in the national mental culture, power of production, security, and prosperity, so is the civilization of the human race only conceivable and possible by means of the civilization and development of the individual nations. [3] [4]

This is the actual legacy of the Right. Not Locke, Mill, Spencer, Hobbes, van Mises, Hayek, or Rand.

But such was the paradigm shift in politics during the Cold War, with disaffected Marxists entering en masse the ranks of the Cold Warriors against the USSR, that by the time the eminent American scholar Christopher Lasch had rejected neo-Marxism he could not find “genuine conservativism” in the USA. He could only find advocates of free trade, which he considered as destructive to tradition and the organic community as the Left. [4] [5]

What Lasch perceived in the early 1970s Oswald Spengler had seen in the aftermath of World War I: that the “scientific socialism” of Marx et al did not transcend capitalism, but reflected it, because both arose within the same Zeitgeist of British materialism and industrialism. [5] [6] As Lasch saw decades later, capitalism shares with the Left a common outlook against the traditional social order, which is the organic community. Carlyle had perceived this in 1840. After World War I, Spengler spoke of “Prussian Socialism,” and Otto Strasser of “German Socialism,” based on pre-capitalist German — and wider European — ethos. To Strasser, “socialism” is synonymous with “conservativism” because it harkens back to the pre-capitalist organic community. Marxism is within the same historical stream as liberalism, Marxism being “a doctrine whose liberal factors necessarily unfit it for the upbuilding of the socialist (i.e. conservative) future, and one whose program cannot but involve it in the decline of liberalism.” As Spengler had stated, Strasser reiterated that “this was simply due to the fact that the longing for socialism began to find expression at a time when the ego idea, liberalism, that is to say, was in the ascendant.” [6] [7]

The fundamental premise of the Right is the dichotomy described by German sociology, of Gemeinschaft versus Gesellschaft; the traditional organic community, or the “modern” doctrine of society as a contract between individuals for their material benefit. Sombart came to regard Marxism as rooted in the latter along with liberalism, as its only goal is to unite individuals for selfish material gain in the name of the proletariat, as liberalism does in the name of the bourgeoisie, which he regarded as the abysmal gulf between British bourgeois philosophy (including Marx) and that of the German (including Carlyle), which he delineated as a difference between the heroic spirit and the commercial or trader’s spirit. [7] [8]

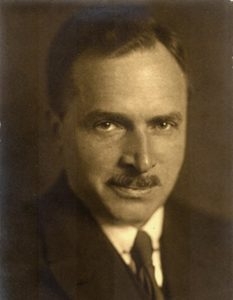

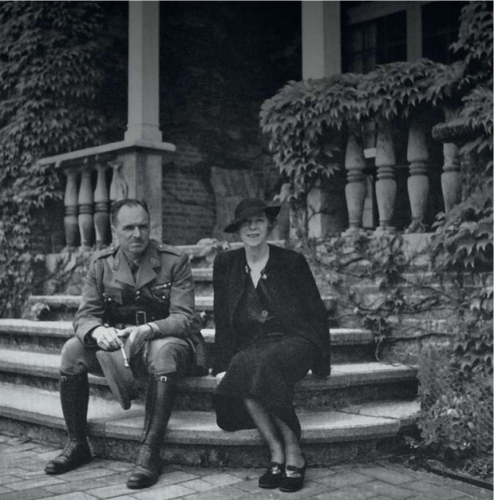

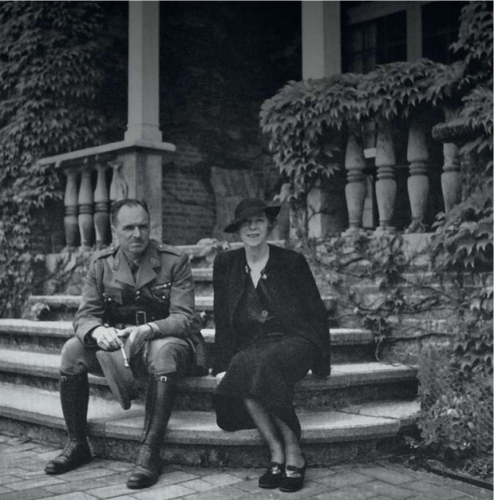

May 1940, de Man with Queen Elizabeth.

Corradini, head of the Italian Nationalist Association, stated at its first congress in 1910, nine years prior to the founding of Mussolini’s fascio, that Italy is a “proletarian nation,” and that “socialism” so far from serving the interests of the “proletarian nations” creates with its internationalism and class struggle a civil war within the social organism. [8] [9] Nine years later, at the Nationalist convention in Rome, Corradini described syndicalism as the means by which the organic social community (Gemeinschaft) can be established; creating “real collaboration, organic, unifying, and complete.” [9] [10]

When a synthesis began to arise from the late 19th century between the elements of the Right and Left, this was a process of the Left turning Right, while elements of the Right were returning to their actual — pre-capitalist — origins. The synthesis became the major “third force” in the world competing against communism and capitalism, and drawing many of the Left’s best thinkers who had already been realizing the limitations of “scientific socialism.”

Even if we consider the terms Left and Right at their most basic level — the seating arrangements of the French Assembly — it might seem odd today, when ideological terms have become obfuscated and origins forgotten, that those on the Right represented the maintenance of tradition, representing the monarchical and Catholic regime that retained a few vestiges of the traditional epoch; those on the Left stood for a bourgeois new order of laissez-faire trade. This bourgeois revolution is a primary part of the Left’s legacy, being considered as a necessary element of the dialectical process of what Marx called the “wheel of history.” [10] [11] It should be kept in mind that Marx, according to this dialectical outlook, stated that socialism could not proceed until capitalism and the bourgeoisie had replaced the vestiges of the traditional order, causing the ruination of peasants, artisans, burghers, and aristocrats. These ideas are expressed most clearly in The Communist Manifesto.

Advocacy of a return to the pre-capitalist order was vehemently denounced by Marx as “reactionism.” [11] [12] To the Rightist this is not regressive, but restorative, as the Right states that there are fundamentals that are timeless, and one might say emanating from an axis; while the “progress” of liberalism and “scientific socialism” is destructive fallacy. [12] [13] Hence, the Right is literally a conservative revolution insofar as “revolution” implies a return to origins. It also means that the liberal-capitalist order requires a complete overturn to restore those origins.

Role of the Bourgeoisie

The French Revolution of 1789 was pivotal and its impact has only increased over the world. From the French Revolution arose both liberal capitalism and the Left. The Revolution abolished the vestiges of the Medieval guilds in France under the Chapelier Law of 1791. These forefathers of “scientific socialism” enacted the free market, standards of production markedly declined, and there was widespread dissatisfaction with such “liberty.” Such was the concern at this destruction of the guilds that the National Assembly in 1795 reiterated they would not be revived, and the prohibition became Article 355 of the Constitution, which meant that a constitutional amendment would be required to reverse the law. In Revolutionary France, the guild era was recalled as one of happiness and plenty. No longer with stability, fraternity (despite the ironic slogan of the Revolution: “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity”), and a higher purpose that the guilds had offered, worker unrest was widespread. The supposed peoples’ representatives expressed concern at mounting worker “insubordination.” There was prolonged debate on the reconstitution of the guilds under Napoleon Bonaparte, but ultimately the laissez-faire radicals won. [13] [14] What replaced the organic community, however debased it had become by that time, was “civil society,” and the “social contract” between individuals, or what the Declaration on the Rights of Man & of the Citizen referred to as the “general will,” enforceable in the name of freedom by death. Joseph de Maistre criticized the Enlightenment notion that a nation could be built on such legalistic artifices that fail to reflect the spirit of a nationality. Of written constitutions as nation-building instruments, he wrote:

There never has existed a free nation which had not, in its natural constitution, germs of liberty as old as itself; and no nation has ever successfully attempted to develop, by its fundamental written laws, other rights than those which existed in its natural constitution. . . . No assembly of men can give existence to a nation. An attempt of this kind ought even to be ranked among the most memorable acts of folly exceeding in folly what all the Bedlams of the world might produce most absurd and extravagant. [14] [15]

Again, with de Maistre, the contrast is between the society that is organic and that which is contractual. Today, “civil society” is regarded as the desirable norm for the entire world.

Crisis of the Left

There were Leftists who regarded the Marxist and other such forms of socialism as inadequate and historical analyses based on nothing more than economic relations as insufficient. Leftist thinkers, Sombart being notable among these, began to see “scientific socialism” — as Marx called it — as an appropriation of the bourgeois capitalist spirit for the proletariat rather than as a transcendence. World War I was the catalyst for the eruption of a discontent that had been growing within the Left. The war had proved that the patria readily transcended class conflict; that as Corradini had stated, the national struggle supplants sectionalism whether of the liberal-bourgeois or “socialist” varieties.

Professor Alfredo Rocco, Italian Minister of Justice (1925-1932), the primary architect of the future corporatist state, began politically as a socialist before joining Corradini’s Nationalist Association. He saw the strengthening of the proletariat as necessary for social cohesion. In his 1920 address to the University of Padua, inaugurating the academic year, he referred to history as one of organic social cycles of birth and decay. Within this, he develops the concept of “unceasing struggle” within every “social body” “between the principle of organization represented by the state and the principle of disintegration, represented by individuals and groups, which tend to disrupt it and lead to its decline and fall.” While the concept is Spenglerian, Rocco was drawing on the Italian philosopher Giovanni Battista Vico, who preempted Spengler by about 180 years — and here we have in Vico another forgotten philosopher of the Right.

Rocco traced the disintegrative impact of liberalism and the role of the bourgeoisie in undermining the social organism — “an amorphous and disorganized mass” in an “individualistic reaction.” The doctrine was provided by the Salon intelligentsia espousing an imaginary “natural law” and by the Encyclopaedists, “and it came to a head politically in the explosion of the French Revolution.” Faced with the reality of governing and of foreign wars, the French revolutionary regime soon had to reimpose the authority of the state, culminating in the genius of Napoleon. Following this epoch there arose again bourgeois liberalism with its atomistic “liberty.” Rocco cogently defines the liberal regime in describing the situation that arose from the tumults of the 19th century:

Rocco traced the disintegrative impact of liberalism and the role of the bourgeoisie in undermining the social organism — “an amorphous and disorganized mass” in an “individualistic reaction.” The doctrine was provided by the Salon intelligentsia espousing an imaginary “natural law” and by the Encyclopaedists, “and it came to a head politically in the explosion of the French Revolution.” Faced with the reality of governing and of foreign wars, the French revolutionary regime soon had to reimpose the authority of the state, culminating in the genius of Napoleon. Following this epoch there arose again bourgeois liberalism with its atomistic “liberty.” Rocco cogently defines the liberal regime in describing the situation that arose from the tumults of the 19th century:

[ind]From that time onwards, the claims of individualism knew no bounds. The masses of individuals wanted to govern the state and govern it in accordance with their own individual interests. The state, a living organism with a continuous existence over the centuries that extends beyond successive generations and as such the guardian of the imminent historical interests of the species, was turned into a monopoly to serve the individual interests of each separate generation. [15] [16]

To restore the social organism against the atomization of liberalism, Rocco urged the integration of the syndicates, or corporations as they were known in Italy since Classical Rome, as integral organs of the social body. Rocco pointed out that liberalism in the name of individual liberty had “destroyed those ancient and venerable organizations, the guilds and corporations of arts and crafts,” which were decreed as abolished on the night of August 4th, 1789 by the French National Assembly, and in the subsequent law of August 14th — 17th 1791. In Italy, the ban was soon lifted, but the corporations did not regain their standing. “Yet professional organization or syndicalism, as it is normally known, or corporatism, to use the more traditional Italian word, is a natural and irrepressible phenomenon to be found in every age. It existed in Greece as well as in Rome, and in the Middle Ages as in modern times.” The disjunction and indeed animosity that had emerged between artisan and owner under modern capitalism could be reconciled within corporatism.

Many Leftists, just as much within the victor states as the defeated, saw the war as a “defeat of socialism.” Lanzillo, a syndicalist on the staff of Mussolini’s socialist newspaper Popolo d’Italia from 1914, wrote in his book The Defeat of Socialism that contrary to socialist expectations, the proletariat of every nation eagerly fought for their national, not international, class interests. “Socialism based its arguments on the dialectical opposition of interests within individual countries, and war showed the possibility of reconciling those interests in the will to defend by force of arms a common heritage and common ideals.” [16] [17] This echoes Sombart’s 1915 work; although Sombart insisted that the “spirit” was uniquely “German,” after the war, it became universal among those who yearned for something more than a return to the decaying pre-war order.

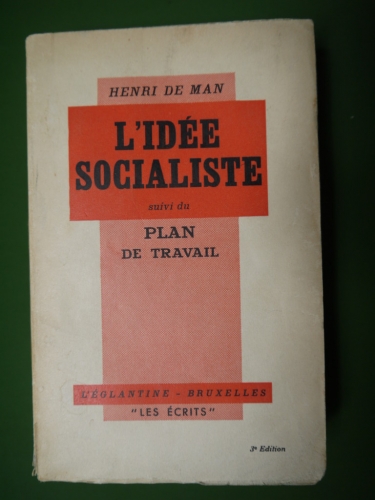

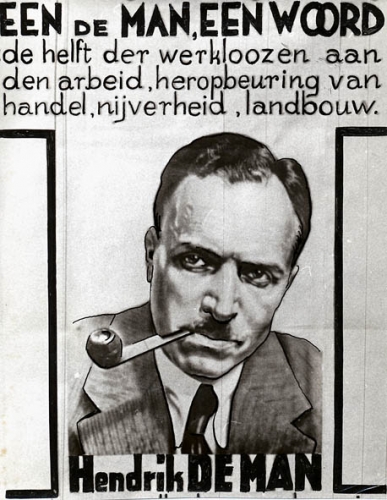

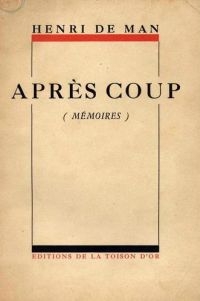

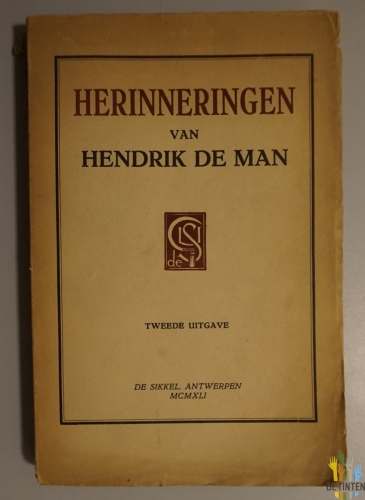

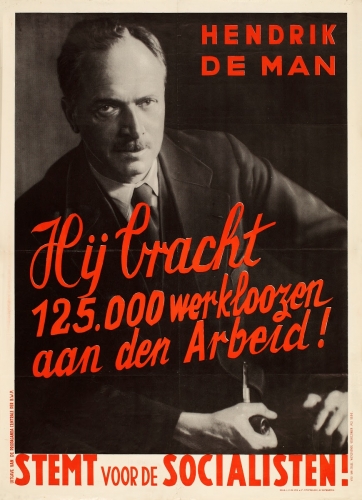

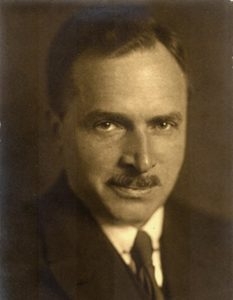

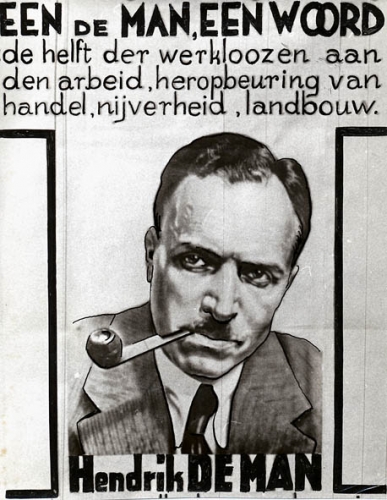

Hendrik de Man and Socialism

Hendrik de Man, leader of the Belgian Workers Party, went so far as to initially cooperate with the German occupation during World War II, seeing it as a blow at the bourgeois spirit of the prior century. Despite this, de Man is still regarded as an important theorist of socialism. His “neosocialism,” also known as “planism,” [17] [19] is a significant ideological development among the Francophone Left. De Man was among the leading Socialists of Europe, having worked with Rosa Luxemburg [20], Karl Liebnecht, Karl Kautsky, and Leon Trotsky [21]. After service in World War I he visited the Soviet Union, lived in Washington, and worked as a professor of economics at the University of Frankfurt.

Marxism, de Man stated, reduces man “to the level of a mere object among the objects of his environment, and these external historical ‘relationships’ are held to determine his volitions and to decide his objectives.” Like many socialists who rejected Marx, World War I was a seminal event for de Man. He wrote in The Psychology of Marxian Socialism:

The war, in which I participated as a Belgian volunteer, shook my Marxist faith to its foundations. It is war-time experience which entitles me to say that my book has been written with blood, though I cannot myself be certain that I have been able to transform that blood into spirit. The conflict of motives whose upshot was that I, an ardent antimilitarist and internationalist, felt it my duty to take up arms against Germany; my disillusionment at the collapse of the International; the daily demonstration of the instinctive nature of mass impulses thanks to which even socialist members of the working class had their minds poisoned with the virus of nationalist hatred; my growing estrangement from most of my sometime Marxist associates, who went over to the bolshevik camp — thanks to all these influences conjoined, I was racked with doubts and scruples whose echoes will be heard in this book. [18] [22]

After the First World War, he withdrew from politics for several years to reflect on his thoughts and life. He conceded that what was required was not merely to “revise” or “adapt” Marxism, but to liquidate it. [19] [23]

In France, Socialist Party leader Marcel Déat, whose “neosocialism” was significantly influenced by de Man, anarcho-syndicalist Georges Valois, and Communist Party eminence Jacques Doriot came to such conclusions. The “British Fascism” of Sir Oswald Mosley had its programmatic origins in his days as a Labour Minister, and the fundamentals remained. Of this post-war situation for socialists, de Man stated:

It is not surprising that socialism is in the throes of a spiritual crisis. The world war has led to so many social and political transformations that all parties and all ideological movements have had to undergo modification in one direction or another, in order to adapt themselves to the new situation. Such changes cannot be effected without internal frictions; they are always attended by growing pains; they denote a doctrinal crisis. [20] [24]

Marxism remained “rooted in the philosophical theories that were dominant during the middle decades of the nineteenth century, theories which may provisionally be summarised in the catchwords determinism, causal mechanism, historicism, rationalism, and economic hedonism.” [21] [25] So far from the bourgeoisie being increasingly proletarianized due to the crisis of capitalism, as Marx had predicted in The Communist Manifesto, de Man saw that “the working class is tending to accept bourgeois standards and to adopt a bourgeois culture.” [22] [26] “In the last analysis, the reason why the bourgeoisie is the upper class to-day, is that everyone would like to be a bourgeois.” [23] [27] Today more than ever it is apparent that the historical dialectic has not unfolded in the manner Marx predicted. The “cult of the masses” was an invention of bourgeois intellectuals including Marx, who were remote from the masses; [24] [28] a “relapse into the naivety of the outworn primitive democratic adoration of the crowd.” [25] [29]

Marxism remained “rooted in the philosophical theories that were dominant during the middle decades of the nineteenth century, theories which may provisionally be summarised in the catchwords determinism, causal mechanism, historicism, rationalism, and economic hedonism.” [21] [25] So far from the bourgeoisie being increasingly proletarianized due to the crisis of capitalism, as Marx had predicted in The Communist Manifesto, de Man saw that “the working class is tending to accept bourgeois standards and to adopt a bourgeois culture.” [22] [26] “In the last analysis, the reason why the bourgeoisie is the upper class to-day, is that everyone would like to be a bourgeois.” [23] [27] Today more than ever it is apparent that the historical dialectic has not unfolded in the manner Marx predicted. The “cult of the masses” was an invention of bourgeois intellectuals including Marx, who were remote from the masses; [24] [28] a “relapse into the naivety of the outworn primitive democratic adoration of the crowd.” [25] [29]

In comparing the pre-capitalist guild era of the Medieval epoch with the capitalist era of production, de Man pointed out that

The essence of the charge brought by Marxism against capitalism is that the capitalist method of production has divorced the producers from the means of production. In actual fact, capitalism has done something much more serious; it has divorced the producer from production, the worker from the work. In this way, it has engendered a distaste for work which is often increased rather than diminished by an improvement in the material circumstances of life, and cannot be cured by any mere change in property relationships.

Especially conspicuous is the contrast between the industrial worker of to-day and the Medieval artisan as a guildsman. The handicraftsman of the Middle Ages might or might not be the owner of his house, his workshop, or his booth; his position might be a good one, financially speaking, or the reverse. But at least he was master of his own work. . .

The craftsman of the Middle Ages took delight in his work; he lived in his work; for him, his work was a means of self-expression. [26] [30]

De Man dealt directly with the workers, and often through his own lack of understanding was taught many lessons on the workers’ ethos that would be regarded as “reactionism” (as Marx puts it in The Communist Manifesto) by those on the Left too imbued with the bourgeois outlook to understand. At one such point, de Man alludes to the personal attachment tradesmen have to their own old toolboxes, an ethos that goes beyond the comprehension of Marxist doctrine (and an attitude that one can still observe among tradesmen and apprentices). [27] [31] He stated that Marxist theories about working-class solidarity lacked an ethos, and were mechanistic. They sought to build something merely on the basis of modes of production. This is the “economic man,” the “hedonist” and “egoist.” [28] [32] It is the same spirit of the merchant referred to by Sombart. The desire for solidarity was born not from this bourgeois outlook, but from the instinct that had existed during the Medieval era; of Christian ethos; that of “craft fraternity” defended by the guilds. [29] [33] Socialism, said de Man, should aim to revive a social ethos that was instinctive [organic], not mechanistic. [30] [34] He alluded to two postulants that serve as an ethical basis for this “new socialism”: “1. Vital values are higher than material values; and of vital values, spiritual values are the highest. 2. The motives of community sentiment are higher than the motives of personal power and personal acquisition.” [31] [35] Again, Sombart had said the same in his wartime appeal.

An additional factor in the fallacy of Marxism was that especially since the First World War the proletariat had become more national and less international. [32] [36] Machinery and modes of production might indeed be international and what is today called globalization shows that capital is an internationalizing tendency, as Marx approvingly predicted. But people are more than their modes of production. [33] [37]

An additional factor in the fallacy of Marxism was that especially since the First World War the proletariat had become more national and less international. [32] [36] Machinery and modes of production might indeed be international and what is today called globalization shows that capital is an internationalizing tendency, as Marx approvingly predicted. But people are more than their modes of production. [33] [37]

De Man saw the socialist movement as intrinsically national and the proletariat as more than a globule of putty to be molded for the purposes of production, whether by liberalism or Marxism:

The French revolution, which was the supreme struggle on the continent of Europe for the realization of the political demands of the bourgeoisie, was (so thought the revolutionists) to culminate in a universal rising of the peoples against the despots, and to make the Declaration of the Rights of Man the constitution of the whole human race. The Goddess of Reason, in whose honor the revolution set up its altars, was to become the deity of all mankind. [34] [38]

National sentiment is an integral part of the emotional content of the socialism of each country. It grows in strength in proportion as the lot of the working masses of any country is more closely connected with the lot of that country itself; in proportion too as the masses have won for themselves a larger place in the community of national civilization. At bottom, this partial absorption of socialist sentiment by national sentiment need not surprise us. We have merely to recognize that it is the return of a sentiment to its source. [Emphasis added]. Socialism itself is the product of the interaction between a given moral sentiment and a given social environment. It is not only the social environment which has a national character. The other factor, likewise, the moral sentiment, has primarily, in different peoples, a peculiar tinge, derived from a peculiar national past. [35] [39]

Hence, de Man recognized that socialism and tradition (that is “the Right”) are, so far from being antithetical, intrinsic each to the other.

Hendrik de Man was condemned as a “collaborator” after World War II and settled in exile in Switzerland. Like others condemned “traitors” and “collaborators,” he had remained in his country during the occupation to try and make something positive from the situation. When the German military occupied Belgium in June 1940, de Man issued a manifesto to the Belgian Workers Party stating that “For the working classes and for socialism, this collapse of a decrepit world, far from being a disaster, is a deliverance.” He had been Minister of Public Works (1934-1935) and of Finance (1936-1938). The failure to see his “Plan” implemented is reminiscent of a similar situation faced by Sir Oswald Mosley with his “Mosley Memorandum” to the Labour Government on the unemployment problem. Like Mosley, he saw that plutocracy could only be defeated by strong government action.

While other Belgian politicians fled the country and formed a government-in-exile, de Man served as de facto Prime Minister for over a year. In 1941, he co-founded with other trade union leaders the Union des Travailleurs Manuels et Intellectuels, which was intended as the basis of a corporatist state above party politics. However, German occupation prevented this from becoming a truly effective organization.

While other Belgian politicians fled the country and formed a government-in-exile, de Man served as de facto Prime Minister for over a year. In 1941, he co-founded with other trade union leaders the Union des Travailleurs Manuels et Intellectuels, which was intended as the basis of a corporatist state above party politics. However, German occupation prevented this from becoming a truly effective organization.

De Man soon fell out with the occupation authorities. Although remaining the primary adviser to King Leopold III and the Queen Mother, he left Belgium in 1941 after talks with the Reich failed to reach a satisfactory conclusion for Belgian sovereignty and he was banned by the occupation authorities from public speaking. He first lived in France, then Switzerland until his death in 1953.

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [40] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [41].

Don’t forget to sign up [42] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Notes

[1] [43] Thomas Carlyle, Past & Present (1843), Book I: “Proem,” Chapter I: “Midas.”

[2] [44] Thomas Carlyle, Chartism (1840), Chapter VII: “Not Laissez-Faire.”

[3] [45] Friedrich List, The National System of Political Economy (1841), Chapter XV: “Nationality and the Economy of the Nation.”

[4] [46] Christopher Lasch, “What’s Wrong with the Right? [47]” Tikkun, No. 1, 1987.

[5] [48] Spengler in The Decline of the West, The Hour of Decision, and Prussianism and Socialism. See for the latter Spengler: Prussianism Socialism and Other Essays (London: Black House Publishing, 2018).

[6] [49] Otto Strasser, Germany Tomorrow (London: Jonathan Cape, 1940), Part III: “The Structure of German Socialism” (4) Marxism, 126.

[7] [50] Werner Sombart, Händler und Helden (Merchants and Heroes, 1915). It seems likely that Spengler was influenced by this book, and Yockey, whether directly or via Spengler. But not all Germans have the “heroic spirit,” and not all British that of the “trader.” In this dichotomy, Marx reflected the “British,” Carlyle the “German”; insofar as each state represented a rival Zeitgeist which conflicted in two world wars. It seems reasonable to conclude that the “trader” spirit, in defeating the “heroic,” was taken over from Britain by the USA after World War II.

[8] [51] Enrico Corradini, The Principles of Nationalism, Report to the First Nationalist Congress, Florence, December 3, 1910.

[9] [52] Corradini, Nationalism and the Syndicates, Rome, March 16, 1919.

[10] [53] Marx’s “wheel of history,” so far from being in the traditional sense, where a culture revolves metaphorically on an axis, in the Evolian sense, proceeds in a straight line called “progress,” until falling into the abyss.

[11] [54] Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto (1848), “Bourgeois and Proletarians.”

[12] [55] Evola referred to the axial basis of civilization in Revolt Against the Modern World; Yeats rendered the idea poetically in “The Second Coming” (1920).

[13] [56] See Michael P. Fitzsimmons, “The Debate on Guilds under Napoleon,” The Proceedings of the Western Society for French History, Vol. 36, 2008.

[14] [57] Joseph de Maistre, Essay on the Generative Principle of Constitutions (1847), Preface.

[15] [58] Alfredo Rocco, The Syndicates & the Crisis within the State, Padua, November 15, 1920.

[ [43]16] [59] Agostino Lanzillo, The Defeat of Socialism (Rome, 1918), Preface.

[17] [60] Named after H. de Man’s “Labor Plan” of 1933 to deal with unemployment.

[18] [61] Hendrik de Man, The Psychology of Marxian Socialism (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Books, 1988 (1928)), 12.

[19] [62] Ibid., 14.

[20] [63] Ibid., 19.

[21] [64] Ibid., 23.

[22] [65] Ibid., 25.

[23] [66] Ibid., 103.

[24] [67] Ibid., 35.

[25] [68] Ibid., 36.

[26] [69] Ibid., 65-67.

[27] [70] Ibid., 75.

[28] [71] Ibid., 127.

[29] [72] Ibid.

[30] [73] Ibid., 131.

[31] [74] Ibid., 189.

[32] [75] Ibid., 303.

[33] [76] Ibid., 313.

[34] [77] Ibid., 321. This cult of the Goddess of Reason was intended as a literal civic religion in Jacobin France to replace Catholicism.

[35] [78] Ibid., 325-326.

En réalité, ce primat de l’économie se révèle une illusion d’optique. Il est d’ailleurs contesté par les mouvements altermondialistes et écologiques, les chiffres de l’abstention électorale et le retour de la rhétorique patriotique. Partout, des appels à une autre « gouvernance » se font entendre. Un nouvel avenir est annoncé, celui du renversement des échanges de marchandises au profit des solidarités sociales. Mais, paradoxalement, la contestation altermondialiste ne remet pas fondamentalement en cause le primat de l’économie : la décroissance, l’inversion des profits et la taxation des bénéfices financiers ne servent qu’à promouvoir une nouvelle révolution matérielle mondiale. Bref, même chez ceux qui souhaitent abolir le capitalisme marchand, tout ne reste qu’économique. Or les données chiffrées ne nous offrent qu’une idée imparfaite des risques à venir. De plus, ces indicateurs complexes se manipulent aisément. La réduction du monde au simple jeu des forces économiques fait finalement obstacle à l’intelligence car elle passe deux dimensions essentielles sous silence : l’affirmation des cultures et la volonté de puissance.

En réalité, ce primat de l’économie se révèle une illusion d’optique. Il est d’ailleurs contesté par les mouvements altermondialistes et écologiques, les chiffres de l’abstention électorale et le retour de la rhétorique patriotique. Partout, des appels à une autre « gouvernance » se font entendre. Un nouvel avenir est annoncé, celui du renversement des échanges de marchandises au profit des solidarités sociales. Mais, paradoxalement, la contestation altermondialiste ne remet pas fondamentalement en cause le primat de l’économie : la décroissance, l’inversion des profits et la taxation des bénéfices financiers ne servent qu’à promouvoir une nouvelle révolution matérielle mondiale. Bref, même chez ceux qui souhaitent abolir le capitalisme marchand, tout ne reste qu’économique. Or les données chiffrées ne nous offrent qu’une idée imparfaite des risques à venir. De plus, ces indicateurs complexes se manipulent aisément. La réduction du monde au simple jeu des forces économiques fait finalement obstacle à l’intelligence car elle passe deux dimensions essentielles sous silence : l’affirmation des cultures et la volonté de puissance.

Or ce qui est vrai pour les empires ne l’est pas moins pour les entreprises, dont la durée de vie et la santé financière sont menacées par leur croyance au mythe techniciste. Ainsi en est-il au dernier stade pour les familles qui se perpétuent dans la longue durée lorsqu’elles adhèrent à des valeurs spirituelles forçant leurs membres à se dépasser ou à l’inverse s’atomisent en une multitude d’individus rivaux, attirés, tels des lucioles, vers le profit qui les calcinera. Les nations durables s’enracinent par conséquent dans des cultures qui peuvent être d’une variété inouïe, mais qui pour perpétuer la vie, doivent pouvoir se renouveler sans pour autant se renier.

Or ce qui est vrai pour les empires ne l’est pas moins pour les entreprises, dont la durée de vie et la santé financière sont menacées par leur croyance au mythe techniciste. Ainsi en est-il au dernier stade pour les familles qui se perpétuent dans la longue durée lorsqu’elles adhèrent à des valeurs spirituelles forçant leurs membres à se dépasser ou à l’inverse s’atomisent en une multitude d’individus rivaux, attirés, tels des lucioles, vers le profit qui les calcinera. Les nations durables s’enracinent par conséquent dans des cultures qui peuvent être d’une variété inouïe, mais qui pour perpétuer la vie, doivent pouvoir se renouveler sans pour autant se renier.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

The “Right” has a rich but obscured legacy that revolts against capitalism. The “Right” is restorative, and arises when a culture-organism begins to decay. The works of Thomas Carlyle, an essay, Chartism (1840), and the book Past & Present (1843) could be the ideological basis of a true British Right, in which Carlyle condemns free trade from a conservative position. In these, he considered the supposed panacea of universal franchise and decried the debased state of the Aristocracy, which should be replaced with an “aristocracy of merit.” Carlyle stated that free trade would be a harbinger of “social revolution.” (When Karl Marx later said the same, he meant it, contrary to Carlyle, in a positive sense.) Carlyle condemned “Mammon,” materialism, and the “money nexus” of the bourgeoisie, and stated that the problems of the British were fundamentally spiritual and moral, from whence a repudiation of the money-ethos that dominated Britain should proceed. Carlyle did not write in the same stream as the British utilitarian philosophers from whom liberalism arose. He wrote in a more Occidental sense in repudiating the trade and commercial mentality that had long pervaded British thinking, politics, and foreign policy; bourgeois and Whig, as Spengler and Werner Sombart pointed out. Yockey classified Carlyle among the few British philosophers writing from an “organic” perspective of history.

The “Right” has a rich but obscured legacy that revolts against capitalism. The “Right” is restorative, and arises when a culture-organism begins to decay. The works of Thomas Carlyle, an essay, Chartism (1840), and the book Past & Present (1843) could be the ideological basis of a true British Right, in which Carlyle condemns free trade from a conservative position. In these, he considered the supposed panacea of universal franchise and decried the debased state of the Aristocracy, which should be replaced with an “aristocracy of merit.” Carlyle stated that free trade would be a harbinger of “social revolution.” (When Karl Marx later said the same, he meant it, contrary to Carlyle, in a positive sense.) Carlyle condemned “Mammon,” materialism, and the “money nexus” of the bourgeoisie, and stated that the problems of the British were fundamentally spiritual and moral, from whence a repudiation of the money-ethos that dominated Britain should proceed. Carlyle did not write in the same stream as the British utilitarian philosophers from whom liberalism arose. He wrote in a more Occidental sense in repudiating the trade and commercial mentality that had long pervaded British thinking, politics, and foreign policy; bourgeois and Whig, as Spengler and Werner Sombart pointed out. Yockey classified Carlyle among the few British philosophers writing from an “organic” perspective of history. Previously, in his essay Chartism, Carlyle had appealed not to class war but to class unity among fellow Britons, high-born and low, pointing out that the ruling classes did not even realize there was a problem to be solved, much to their own danger:

Previously, in his essay Chartism, Carlyle had appealed not to class war but to class unity among fellow Britons, high-born and low, pointing out that the ruling classes did not even realize there was a problem to be solved, much to their own danger:

Rocco traced the disintegrative impact of liberalism and the role of the bourgeoisie in undermining the social organism — “an amorphous and disorganized mass” in an “individualistic reaction.” The doctrine was provided by the Salon intelligentsia espousing an imaginary “natural law” and by the Encyclopaedists, “and it came to a head politically in the explosion of the French Revolution.” Faced with the reality of governing and of foreign wars, the French revolutionary regime soon had to reimpose the authority of the state, culminating in the genius of Napoleon. Following this epoch there arose again bourgeois liberalism with its atomistic “liberty.” Rocco cogently defines the liberal regime in describing the situation that arose from the tumults of the 19th century:

Rocco traced the disintegrative impact of liberalism and the role of the bourgeoisie in undermining the social organism — “an amorphous and disorganized mass” in an “individualistic reaction.” The doctrine was provided by the Salon intelligentsia espousing an imaginary “natural law” and by the Encyclopaedists, “and it came to a head politically in the explosion of the French Revolution.” Faced with the reality of governing and of foreign wars, the French revolutionary regime soon had to reimpose the authority of the state, culminating in the genius of Napoleon. Following this epoch there arose again bourgeois liberalism with its atomistic “liberty.” Rocco cogently defines the liberal regime in describing the situation that arose from the tumults of the 19th century:

Marxism remained “rooted in the philosophical theories that were dominant during the middle decades of the nineteenth century, theories which may provisionally be summarised in the catchwords determinism, causal mechanism, historicism, rationalism, and economic hedonism.”

Marxism remained “rooted in the philosophical theories that were dominant during the middle decades of the nineteenth century, theories which may provisionally be summarised in the catchwords determinism, causal mechanism, historicism, rationalism, and economic hedonism.”  An additional factor in the fallacy of Marxism was that especially since the First World War the proletariat had become more national and less international.

An additional factor in the fallacy of Marxism was that especially since the First World War the proletariat had become more national and less international.  While other Belgian politicians fled the country and formed a government-in-exile, de Man served as de facto Prime Minister for over a year. In 1941, he co-founded with other trade union leaders the Union des Travailleurs Manuels et Intellectuels, which was intended as the basis of a corporatist state above party politics. However, German occupation prevented this from becoming a truly effective organization.

While other Belgian politicians fled the country and formed a government-in-exile, de Man served as de facto Prime Minister for over a year. In 1941, he co-founded with other trade union leaders the Union des Travailleurs Manuels et Intellectuels, which was intended as the basis of a corporatist state above party politics. However, German occupation prevented this from becoming a truly effective organization.