Albert Camus

Trans. Joseph Laredo

The Stranger

London: Penguin, 2000 (1942)

“I love my country too much to be a nationalist.”

— Attributed to Albert Camus

Whenever I watch Pontecorvo’s iconic movie The Battle of Algiers (1966), I find myself thinking of the Gitane-smoking and brilliantine-coiffured Albert Camus. I’m especially reminded of him in the scene where a gang of young Europeans lean against a shop window and watch as Ali, the young Arab protagonist, crosses the street and passes a noisy bar. A blond youth pushes a chair in front of him, sending Ali head-over-heels, stumbling to the floor. Before a devil-may-care smirk can even appear on the callous face of the Pied-Noir, the Arab stares up at him with utter hatred and launches headfirst into his enemy.

Whenever I watch Pontecorvo’s iconic movie The Battle of Algiers (1966), I find myself thinking of the Gitane-smoking and brilliantine-coiffured Albert Camus. I’m especially reminded of him in the scene where a gang of young Europeans lean against a shop window and watch as Ali, the young Arab protagonist, crosses the street and passes a noisy bar. A blond youth pushes a chair in front of him, sending Ali head-over-heels, stumbling to the floor. Before a devil-may-care smirk can even appear on the callous face of the Pied-Noir, the Arab stares up at him with utter hatred and launches headfirst into his enemy.

Franco Solinas’ script perfectly captures the moment on screen:

Using his head, Ali rams into the youth’s face, striking him in the nose and splurting blood everywhere. The youth is unable to shout. He opens his mouth in the attempt, but the only result is a gurgling sound and blood. His friends intervene. Ali is surrounded. The police arrive. A mass of people jump on Ali, kicking him and striking him with their fists as long as they please. Finally, the police aid Ali and disperse the crowd.

Defiant, Ali “pays no heed to the blows, the shouts, the spitting, but seems neither to see nor hear, as if he were already resigned to having lost the battle this time, and was preparing to wait patiently for a better chance. He is walking with an unfaltering step. His face is emotionless, oval, swarthy. His hair black and wavy, his forehead low and wide; his eyes large and slanted with eyelids somewhat lowered, his mouth firm and proud.”

It is the unmistakable image of the Gaul confronting the Moor, during Albert Maquet’s “invincible summer” of Algeria. A societal fissure ran right through the Kasbah and the mountainous terrain of the parched Tassili n’ Ajjer just as it did between the Jews and Palestinians along the banks of the Jordan River and through the black ghettos in American cities in the 1960s.

The testosterone-fueled tension captured in Ali’s street confrontation is similarly rendered in Camus’ The Stranger, where the local Pied-Noir lads with their “hair greased back, red ties, tight fitting jackets with embroidered handkerchiefs in their top pockets and square-toed shoes. . . laugh noisily as [girls] went by.” Camus’ hero Meursault “knew several of the girls and they waved to me.”

The same sort of girls are later blown to pieces in The Battle of Algiers when Ali dispatches his female Fedayeen to exact revenge:

Djamila, the girl who in January, in rue Random, gave the revolver to Ali la Pointe, is now standing in front of a large mirror. She removes the veil from her face. Her glance is hard and intense; her face is expressionless. The mirror reflects a large part of the room: it is a bedroom. There are three other girls.

There is Zohra, who is about the same age as Djamila. She undresses, removing her traditional costume, and is wearing a slip . . . There is Hassiba who is pouring a bottle of peroxide into a basin. She dips her long black hair into the water to dye it blond.

Every action is performed precisely and carefully. They are like three actresses preparing for the stage. But there is no gaiety; no one is speaking. Only silence emphasizes the detailed rhythm of their transformation . . . Djamila’s lightweight European dress of printed silk . . . Zohra’s blouse and short skirt to her knees . . . make-up, lipstick, high-heeled shoes, silk stockings . . . Hassiba has wrapped her hair in a towel to dry it . . . a pair of blue jeans, a striped clinging tee-shirt . . . Her blond hair is now dry. She ties it behind in a ponytail. Hassiba has a young, slim figure. She seems to be a young European girl who is preparing to go to the beach.

Pontecorvo’s depiction of guerrilla warfare way back when in Algiers was prophetic. It’s now reenacted week by week with real daggers, bullets, and plastic explosives in the towns and cities of 21st-century Europe. Solinas’ script continues:

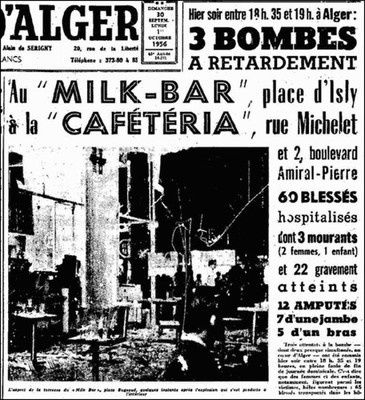

MILK BAR. EXPLOSION. OUTSIDE. DAY.

The jukebox is flung into the middle of the street. There is blood, strips of flesh, material, the same scene as at the Cafeteria; the white smoke and shouts, weeping, hysterical girls’ screams. One of them no longer has an arm and runs around, howling despairingly; it is impossible to control her. The sound of sirens is heard again. The crowd of people, the firemen, police, ambulances all rush to the scene from Place Bugeand.

The ambulances arrive at rue Michelet. They are already loaded with dead and wounded. The relatives of the wounded are forced to get out. The father of the child who was buying ice cream seems to be in a daze: he doesn’t understand. They pull him down by force. The child remains there, his blond head a clot of blood.

These communal antagonisms had been simmering for years. The insurgent Front de Liberation Nationale (FLN), just like their Etoile Nord-africaine predecessors, was attacking isolated farmsteads and police stations. The Pieds-Noir responded in kind, holding meetings with banners that read “le juif parasite,” and Lucien Bellat’s Unions latines was breaking up seditionist gatherings organized by communists and Muslims in places like Sidi-Bel-Abbes in June 1936.

Algeria was a bubbling cauldron that was rapidly reaching its boiling point, and it was here that Camus was born into a poor family in a white ghetto. He was surrounded by a Pied-Noir community that felt psychologically under siege. Many joined the colonial chapters of metropolitan leagues like the Action francaise, Jeunesses patriots, the Croix de Feu, and the Parti populaire francais during the interwar years.

Camus’ latter-day anti-colonial critics dismiss his much-vaunted socialist credentials despite his joining the Communist Party in 1935, becoming editor-in-chief of the resistance journal Combat during the war years, his well-known sympathies for the Arab peoples, his support for the Blum-Viollette proposal to grant Algerians full French citizenship, and of course, his searing allegory of fascism in his novel The Plague [4] (1947).

Instead, Camus’ postmodern detractors claim that he had thoroughly imbibed the inherent racism of his forebears. Ralph Flowers cites excerpts from The Stranger as evidence of Camus’ subconscious “hatred” in Camus and Racism (1969): “Why in the fictional works L’Etranger, La Peste, and La Chute (1956) does Camus either treat the Arab cursorily or else delete completely?”

The late Palestinian academic Edward Said, author of Culture and Imperialism (1993), describes Camus as having an “incapacitated colonial sensibility,” arguing:

The plain style of Camus and his unadorned reporting of social situations conceal rivetingly complex contradictions . . . unresolvable by rendering, as critics have done, his feelings of loyalty to French Algeria as a parable of the human condition.

French historian Benjamin Stora describes The Stranger’s central character as “paradoxical” and the result of “double positioning.” Mary Ann & Eric Witt’s assert in their seminal piece “Retrying The Stranger” (1977) that the “race question” was central to the story. Tulshiram C. Bhoyar asserts that “Meursault displays misogynistic attitudes toward women, perpetrates prejudicial acts against native people, and commits a callous crime against an indigenous person” in his paper “The Stranger: A Study of Sexism, Racism and Colonialism,” published in Epitome in 2016.

French historian Benjamin Stora describes The Stranger’s central character as “paradoxical” and the result of “double positioning.” Mary Ann & Eric Witt’s assert in their seminal piece “Retrying The Stranger” (1977) that the “race question” was central to the story. Tulshiram C. Bhoyar asserts that “Meursault displays misogynistic attitudes toward women, perpetrates prejudicial acts against native people, and commits a callous crime against an indigenous person” in his paper “The Stranger: A Study of Sexism, Racism and Colonialism,” published in Epitome in 2016.

Bhoyar continues:

Jean-Paul Sartre, the existentialist philosopher, in his essay “An Explication of the Stranger” (1947), considered him as an existential hero who is free and responsible for his action. Both of them (Camus and Sartre) did not think that the murder committed by Meursault has a political dimension and the legal system of the Pied-Noir French depicted in the novel is oppressive to indigenous Arabs. But this notion is challenged by many modern critics and readers. They think Meursault is a sexist, racist and colonialist hero.

Credible comments when one, like Flowers, notes:

In the first place, Camus writes as a member of the white race. He never tried to assume the role of an Arab . . . Probably the majority of Algerian Europeans were merely indifferent to the abject status of the native race; this was the real crime of Meursault . . . Considering the story solely from the facet of the race problem, Meursault was guilty of a race crime.”

George Heffernan explains in his paper “A Hermeneutical Approach to Sexism, Racism, and Colonialism in Albert Camus’ L’Etranger:”

Camus has created with Meursault an unreflective character whose sexist, racist, and colonialist attitudes are held up to the reflective reader . . . Meursault ignores the screams of the terrified Arab woman, whom Raymond is beating mercilessly . . . He is a racist, because at first he declines to write the letter that Raymond wants him to write to his allegedly unfaithful mistress, but as soon as he discovers that the woman to whom he is to write is an Arab, he complies with Raymond’s request without further ado.

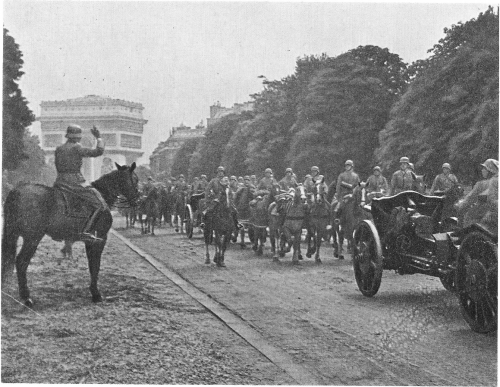

The relevant section in The Stranger, a manuscript that traveled with Camus to France as German troops marched down the Champs Elysee, reads:

He lit a cigarette and told me his plan. He wanted to write her a letter “which would really hurt and at the same time make her sorry.” Then, when she came back he’d go to bed with her and “right at the crucial moment” he’d spit in her face and throw her out.

When he told me the girl’s name I realized she as Moorish. I wrote the letter.

Camus’ daughter Catherine acknowledges this reality, admitting her father is “regarded as a colonialist.” As a result, his books are not part of the school curriculum in Algeria, and the novelist Hamid Grine, author of Camus in the Hookah (2011) declaims that “Algeria has erased him.”

To a certain extent, Camus is indeed a mass of contradictions. He writes so poignantly about an individual Arab in “L’Hote,” and yet the same people are almost completely absent from The Plague. He became the glamour boy that went on to rival Sartre amongst the New Left coterie after the Liberation of France, but objected in disgust to the murderous “Epuration” that followed in its wake. Camus insisted he was a communist, yet never read Das Kapital.

To a certain extent, Camus is indeed a mass of contradictions. He writes so poignantly about an individual Arab in “L’Hote,” and yet the same people are almost completely absent from The Plague. He became the glamour boy that went on to rival Sartre amongst the New Left coterie after the Liberation of France, but objected in disgust to the murderous “Epuration” that followed in its wake. Camus insisted he was a communist, yet never read Das Kapital.

So, what truly motivated Meursault to do what he did on that beach? His fellow Pied-Noir, Raymond, had already told him he’d been followed all day by a group of Arabs and one of them was the brother of his former mistress. “If you see him near the house this evening when you come home, warn me.”

Those descriptions from his essay “Summer in Algiers” (1939), of “the beauty of the race,” “the gentle warm water and the brown bodies of the women,” and “the old men sitting at the back of cafes listening to young men with brilliantined hair boasting of their exploits,” come to mind.

Those same hormone-infused images discussed earlier, what Pontecorvo captures so clearly in the street fight between Ali and the white boy, must surely go some way to explaining Meursault’s fateful actions in Camus’ disturbing novella:

I took a step, just one step forward. And this time, without sitting up, the Arab drew his knife and held it out towards me in the sun. The light leapt up off the steel and it was like a long, flashing sword lunging at my forehead. At the same time all the sweat that had gathered in my eyebrows suddenly ran down over my eyelids, covering them with a dense layer of warm moisture. My eyes were blinded by this veil of salty tears. All I could feel were the cymbals, the sun was clashing against my forehead and, indistinctly, the dazzling spear still leaping off the knife in front of me. It was like a red-hot blade gnawing at my eyelashes and gouging my stinging eyes. That was when everything shook. The sea swept ashore a great breath of fire. The sky seemed to be splitting from end to end and raining down sheets of flame. My whole being went tense and I tightened my grip on the gun. The trigger gave, I felt the underside of the polished butt and it was there, in that sharp and deafening noise, that it all started. I shook off the sweat and the sun. I realized I’d destroyed the balance of the day and the perfect silence of this beach where I’d been happy. And I fired four more times at a lifeless body and the bullets sank in without leaving a mark. And it was like giving four sharp knocks at the door of unhappiness.

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [5] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [6].

Don’t forget to sign up [7] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.