Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

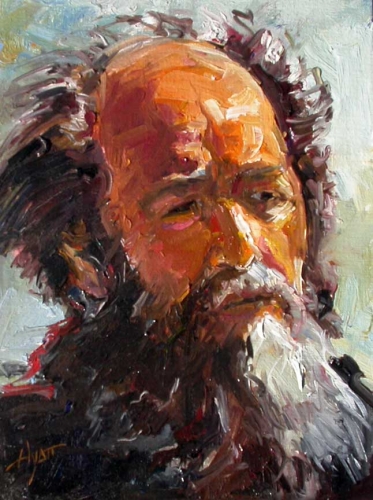

Known mostly as a novelist, memoirist, and historian, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn had actually completed four plays before his first novel, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, was published in 1962. He composed his first two, Victory Celebrations and Prisoners, while a zek in the Soviet Gulag system in 1952. These Solzhenitsyn composed in verse and memorized before burning since prisoners were forbidden to own even scraps of paper. His third play, the title of which is most commonly translated into English as The Love-Girl and the Innocent, he composed outside of the gulag in 1954 while recovering from cancer. In writing Love-Girl, he rejoiced in his ability to actually type and hide his manuscript, rather than keep it all bottled up in his head. [1] [1] Solzhenitsyn composed his final play, Candle in the Wind, in 1960 in an earnest attempt to become a Soviet playwright. Where his earlier plays exposed the evil and corruption of the gulag system — and beyond that, impugned the Soviet Union for its unworkable Marxist-Leninist ideology, disastrous collectivization policies, totalitarian government, and ubiquitous cult of personality in Stalinism — Candle in the Wind avoided politics altogether. It takes place in an unspecified international setting and focuses on the dangerous effects of untrammeled technological progress on the human soul. Of all his plays, Candle in the Wind has the least relevance to the political Right. It also cannot be classified as a prison play, despite how its main character had recently been released from prison.

It would be fair to describe Solzhenitsyn’s first two prison plays as “apprentice works,” in the words of his biographer Michael Scammell. [2] [2] And this is not just in comparison to Solzhenitsyn’s most famous and successful volumes such as One Day and the sprawling Gulag Archipelago. Victory Celebrations and Prisoners do come across as uneven and amateurish. Excessive dialogue makes the reading tedious at times. Solzhenitsyn always had the historian’s impulse to explain and the prophet’s impulse to warn, and seemed to doggedly follow both impulses while writing these plays. As a result, purely narrative elements such as plot and character tend to suffer. Further, many of the themes appearing in his prison plays resurface in more complete form in both One Day and Gulag as well as in his other early novels Cancer Ward and In the First Circle.

Regardless, it is in his three prison plays where Solzhenitsyn’s conservative, Christian, ethnonationalist, and anti-Leftist outlook appears as firm as it does in his later works. It’s as if the man never changed, other than spending the last forty-eight years of his life not writing plays. Even if he had stopped writing altogether by 1960, his prison plays still would have had value to the Right for their keen perception of human nature under the most trying circumstances as well as for their conveyance of the cruelties and absurdities brought about by an oppressive communist ideology that is wholly at odds with human nature. That Solzhenitsyn had produced works that were much greater than these three plays later in his career is no reason for any student of the Right to exclude them from study.

Victory Celebrations

Burdened with a loose plot, excessive dialogue, and an awkwardly large cast of characters, Victory Celebrations (also called Feast of the Conquerors) takes place during the last days of World War II in which a Soviet artillery battalion prepares a lavish victory banquet in the Prussian mansion they had just captured. The play switches back and forth from the minor characters opining their various frustrations with the Soviet regime to what could be a political — potentially deadly — love triangle. This relationship is the heart of the play and produces its only real suspense, brief and poignant as it is.

Galina, a Russian girl living in Vienna, had traveled to Prussia to be with her fiancé who is fighting with the doomed Russian Liberation Army (a force of disgruntled Red Army POWs and anti-Soviet, pro-White Russian émigrés whom had been conscripted by the Germans). Before the story begins, however, she is captured by the battalion and convinces them that she had been a prisoner of the Germans working as a slave girl. Believing her, they invite her to take part in the upcoming celebration.

Counter-intelligence officer Gridnev, however, sees through her and suspects that she is a spy. Any Russian person who has had exposure to the enemy must be held suspect, and Gridnev quickly threatens her with imprisonment if she does not confess all. But Galina is also beautiful, and Gridnev soon finds himself falling in love (or lust) with her. This causes him to append a promise to his threats — if she sleeps with him, he’ll protect her.

While agonizing over this dilemma, Galina meets Captain Nerzhin, a childhood friend of hers. To him, she tells the truth. Nerzhin, being an honest and honorable soldier, empathizes and sees the justice in her position. How could not when Galina delivers a speech such as this?

The U.S.S.R.! It’s impenetrable forest! A forest. It has no laws. All it has is power — power to arrest and torture, with or without laws. Denunciations, spies, filling in of forms, banquets and prizewinners, Magnitogorsk and birch-bark shoes. A land of miracles! A land of worn-out, frightened, bedraggled people, while all those leaders on their rostrums. . . each one’s a hog. The foreign tourists who see nothing but well organized collective farms, Potyemkin style. The school-children who denounce their parents, like that boy Morozov. Behind black leather doors there are traps rather than rooms. Along the rivers Vychegda and Kama there are camps five times the size of France. Wherever you look you see epaulettes with that poisonous blue strip; you see widows, whose husbands are still alive. . .

Now Nerzhin faces a dilemma of his own: shepherding this woman to her fiancé just as Soviet forces are about to crush the Russian Liberation Army will not only be physically dangerous but will make himself vulnerable to a charge of treason. Can he trust anyone in his battalion? Yes, his fellows may see through the corruption and hypocrisy of the Soviet authorities or find fault with Marxism. For example, one tells the harrowing story of how a series of unjust NKVD arrests nearly wiped out an entire town. Another relays the humorous story of how, as an art student, his instructors imagined they saw a swastika in his painting. Despite this, these men wish to survive in the current system, as absurd as it is. They just don’t want to think about it, and thus choose to bow to evil.

Major Vanin says it best:

Thinking is the last thing you want to do. There is authority. There are orders. No one grows fat from thinking. You’ll get your fingers burnt from thinking. The less you know, the better you sleep. When ordered to turn that steering wheel, you turn it.

But with Galina, there is clearly so much more. During her dialogue with Nerzhin, she keeps distinguishing “us” from “them,” and soon a leitmotiv evolves involving loyalty. Galina expresses loyalty to the Russian people and never doubts herself. Nerzhin professes loyalty to the Russian nation — or, at the very least, its military. Meanwhile, Gridnev expresses loyalty to the current Russian government and its inhuman machinations as laid down by the genocidal Stalin. Of course, Gridnev never strays far from his own selfish designs.

Contemporary Soviet audiences, likely still bruising from the Second World War, would most likely have reacted negatively to the Galina character simply for her traitorous support of the RLA. Nevertheless, later audiences, even Russian ones, carry less baggage and will likely see her as the most sympathetic character in the play. At one point, she rejects the terms “Comrade” and “Citizen” and avers that the more traditional courtesy titles of “Sir” and “Madam” are more civilized. She had studied music in Vienna and remains in thrall of great Germanic classical composers such as Mozart and Haydn despite her love of Russia. Clearly, she represents the world that preceded the Soviets. She is the only tragic character in the story, since she symbolizes Solzhenitsyn’s own ethnonationalism, but only under a cloud of death or unspeakable oppression. She’s also the only character moved enough by romantic love to put herself at great risk — even if all it will amount to is her dying by her lover’s side in a hail of artillery fire.

Solzhenitsyn could express his sympathy for this heartbreaking character (and presage the stirring ending of his story Matryona’s House) no better than in the admiring words of Nerzhin:

“I’ve no fears for the fate of Russia while there are women like you.”

Prisoners

Originally titled Decembrists Without December, Prisoners suffers to a greater extent than Victory Celebrations from a thin, meandering plot, a bloated dramatis personae, and excessive dialogue. It lacks even the scraps of narrative formalism found in the earlier play, and instead resembles the dialogues of Plato for of its reliance upon dialectic. The events take place in a gulag wherein the mostly-male cast discuss the absurdities of Soviet oppression, argue the merits and demerits of communism, and endure ludicrous interrogations from counter-intelligence officers. Most of the characters were based on people Solzhenitsyn himself knew. Further, several of the characters appear in later, more famous works, such as Vorotyntsev (The Red Wheel), Rubin (In the First Circle), and Pavel Gai (The Love-Girl and the Innocent).

While much weaker than Victory Celebrations in terms of plot, character, and resolution, Prisoners far surpasses it in astute political commentary as well as in philosophical and historical discourse. In its many debates, Solzhenitsyn does not always demonize the representatives of the Soviet system and sometimes puts wise, thoughtful, or otherwise honest words in their mouths. This leads to some fascinating reading (as opposed to what would seem like tedious chatting onstage). On the whole, however, Prisoners devastates the Soviet Union in a way that would have invited much more than mere censure in that repressive regime. Solzhenitsyn had to keep the play close to his chest for many years, and revealed its existence only after his exile in the West during the 1970s. Had the KGB ever acquired the play, it is likely there would not have been an exile for Solzhenitsyn at all.

Due to the narrative’s unmoored rambling, examples of Solzhenitsyn’s incisive observations can appear with little context and in list form. The relevance to the broader struggle of the Right in all cases should become clear.

We clutch at life with convulsive intensity — that’s how we get caught. We want to go on living at any, any price. We accept all the degrading conditions, and this way we save — not ourselves — we save the persecutor. But he who doesn’t value his life is unconquerable, untouchable. There are such people! And if you become one of them, then it’s not you but your persecutor who’ll tremble!

Far too many on the Right today meekly accept the degrading, second-class citizenship imposed upon us by the racial egalitarian Left. If more of us could value our lives a little less and the Truth a little more, perhaps this unnatural state of affairs could be overturned.

Here, now, we’re all traitors to our country. Cut down the raspberries — mow down the blackcurrants. But that’s not what I got arrested for. I got arrested for infringing on the regulations. I issued extra bread to the collective farm women. Without it, they would have died before the spring. I wasn’t doing it for my own good — I had enough food at home.

Aside from revealing the murderous lack of concern that the Soviet authorities had for their own people, this passage reveals how the Left does not merely value some lives over others but becomes by policy quite hostile to those lives it values least. In today’s struggles, whites in the West who act in their racial interests are meeting with increasing hostility from our Leftist elites, while these same elites actively encourage non-whites to act in their racial interests.

Of course, Solzhenitsyn’s proud ethnonationalism (as expressed by his angst-filled love for Russia) shines through the text as well.

They are ringing the bell. They are ringing for Vespers. . . O Russia, can this ever come back again? Will you ever be yourself? I have lived on your soil for twenty-six years, I spoke Russian, listened to Russian, but never knew what you were, my country! . . .

In some cases, the dialogue becomes downright witty. Take, for example, the absurd interrogation scene between intelligence officer Mymra and Sergeant Klimov, who had been captured in battle by the Germans:

Mymra: Prisoner Klimov. You are here to answer questions, not to ask them. You could be locked up in a cell for refusing to answer questions. Personally, we are ready to die for our leader. Question three: what was your aim when you gave yourself up? Why didn’t you shoot yourself?

Klimov: I was waiting to see if the Divisional Commander would shoot himself first. However, he managed to escape to Moscow by ‘plane out of the encirclement and then got promoted.

Mymra (writing down): Answer. I gave myself up, my aim being to betray my socialist country. . .

Klimov: We-ell, well. You can put it like that…

The Rubin character in Prisoners is no different than his namesake in In the First Circle — a friendly, erudite apologist for communism, and clearly Jewish. Just as in the novel, Prisoner’s Rubin insists that he’d been incarcerated by mistake and that, regardless of his personal circumstances, he remains a true believer in the Soviet system. At one point, in the middle of the play, he is beset upon by his angry co-inmates who challenge him to defend Soviet atrocities such as blockading Ukraine and starving millions into submission. Rubin explains that the great socialist revolutions and slave rebellions of the past had failed because they showed too much leniency towards their former oppressors. They doubted the justice of their cause. He then praises the Soviet Revolution as the product of “unconquerable” science and laments that it has had only twenty-five years to produce results.

. . . you unhappy, miserable little people, whose petty lives have been squeezed by the Revolution, all you can do is distort its very essence, you slander its grand, bright march forward, you pour slops over the purple vestments of humanity’s highest dreams!

Rubin fixates upon the same wide, historical vista that all Leftists do when they wish to explain away failure or atrocity. Conservative debunking of this arrogant folly is as old as Edmund Burke. In Solzhenitsyn’s case, however, he depicts it with almost cringe-worthy realism when he humanizes Rubin as a reasonable and enthusiastic, if misguided, adherent of the Left. We actually grow to like Rubin, especially at the end of the play when he leads a choir of zeks in song as Vorotyntsev contemplates his fate with the others.

The most memorable scene in Prisoners occurs towards the end when Vorotyntsev debates a dying counter-intelligence officer named Rublyov. In this debate we have perhaps Solzhenitsyn’s most eloquent affirmation of the Right as a way of life, and not just as a reaction to the totalitarian Left. Vorotyntsev claims to have fought in five wars on the side of Monarchy or Reaction — all of which were ultimately lost: the Russian-Japanese War, World War I, the Russian Civil War, the Spanish Civil War, World War II (on the side of the Russian Liberation Army). When Rublyov taunts him for this colossal losing streak, Vorotyntsev speaks of “some divine and limitless plan for Russia which unfolds itself slowly while our lives are so brief” and then responds that he never wavered in his fight against the Left because he felt the truth was always on his side. All that Rublyov ever had on his side was ideology. He explains:

You persecuted our monarchy, and look at the filth you established instead. You promised paradise on earth, and gave us Counter-Intelligence. What is especially cheering is that the more your ideas degenerate, the more obviously all your ideology collapses, the more hysterically you cling to it.

When Rublyov accuses the Right of having its own executioners, Vorotyntsev responds, “not the same quantity. Not the same quality,” and proceeds to compare the twenty thousand political prisoners of the Tsar to the twenty million political prisoners of the Soviets.

The horror is that you grieve over the fate of a few hundred Party dogmatists, but you care nothing about twelve million hapless peasants, ruined and exiled in the Tundra. The flower, the spirit of an annihilated nation do not exude curses on your conscience.

In this, Vorotyntsev makes the crucial point of the Right’s moral superiority to the Left. Note his similarity to Rubin in positing a plan as broad as history. For Rubin, however, it is Man’s plan, an atheist’s plan. It is hubris in action, a contrivance of pride. For Vorotyntsev, on the other hand, it is God’s plan — not something he can begin to understand. All he can do is to live according to Truth as he sees it and according to his nature as a human being.

It’s hard to find a more stark distinction between Left and Right than this.

The Love-Girl and the Innocent

Of Solzhenitsyn’s prison plays, The Love-Girl and the Innocent works best. This perhaps explains why it has been staged most often and continues to be put on today. Notably, the BBC produced a television adaptation of Love-Girl in 1973. Love-Girl resembles most closely what most people expect when they read or see a play: Four acts; a beginning, middle, and end; three-dimensional, evolving characters; and a plot filled with conflict, action, and suspense. We could quibble with some of Solzhenitsyn’s authorial choices, such as making the lead character Nerzhin too passive towards the end, employing too many characters (again), or his general lack of focus regarding some of the plot. Nevertheless, that Solzhenitsyn manages to pursue many of the profound themes from Victory Celebrations and Prisoners to their poignant conclusions in Love-Girl as well as explore new ones that would reach their apotheosis in later works such as Gulag Archipelago makes Love-Girl and the Innocent, in this reviewer’s opinion, the first of Solzhenitsyn’s great narrative works.

As in Victory Celebrations, we have a potentially deadly love triangle — but one that achieves greater meaning since the audience can now experience the love and all its wide-ranging consequences. In Victory Celebrations, the story takes place during a lull in the action, with all the real action having already happened or will happen in the near future. The battalion had just captured a mansion and plans to advance on the RLA’s position the next day. By the play’s end, Galina’s fate swings between Gridnev’s protection and Nerzhin’s. Will she become Gridnev’s mistress? Will she be shot or be incarcerated in a gulag? Will Nerzhin take her to her fiancé before the Soviet forces attack? Will she even survive? Note also how this love triangle is not entirely real since Nerzhin, despite his demonstrable affection for Galina, can only serve as a stand-in for her fiancé.

In Love-Girl, all the appropriate action happens on stage and in the here and now. There are no stand-ins. It takes place in a gulag in 1945 where the love is real, agonizing, and immediate. It is also multifaceted, since there are technically two love triangles occurring simultaneously. The “love-girl” of the title is a beautiful and compassionate female inmate named Lyuba, while the “innocent” is Rodion Nemov, an officer recently taken in from the front who is committed to behaving as honorably as possible while in the gulag. The third point in the triangle is Timofey Mereshchun, the prison’s fat, repulsive doctor who promises Lyuba privileges and protection in return for sex. He also has the power to send her off to camps in much harsher climates where her chances of survival would become drastically reduced.

The other love triangle involves another beautiful female inmate named Granya. She is a former Red Army sniper incarcerated not for political reasons, like many of the others, but because she murdered her husband while on furlough after finding him in flagrante delicto with another woman. It’s as if Solzhenitsyn could not decide which woman he was in love with more while writing the play. The men vying for Granya’s affections are an honest and feisty bricklaying foreman named Pavel Gai (first seen in Prisoners) and the corrupt and cruel camp commandant Boris Khomich.

Aside from Solzhenitsyn’s now-familiar themes of ethnonationalism, ethno-loyalty, exposing Soviet atrocities, and impugning communist ideology, Love-Girl also introduces the theme of honor vs. corruption. When the play begins, Nemov is responsible for increasing efficiency in prison work. And he does a fine job, noting how the camp authorities could increase productivity by easing up on the harsh exploitation of the prisoners and cutting much of the self-serving and politically-appointed administrative personnel. He quickly runs afoul of the shady and perfidious ruling class of the camp, however, when he demands that the bookkeeper Solomon turn over a recent shipment of boots to the workers rather than divvy them up among his cronies.

Solomon, along with Mereshchun and Khomich, take their revenge soon after when they manipulate the drunken and irresponsible camp commandant Ovchukhov into transferring Nemov to general work duties while replacing him with the depraved Khomich. In the battle between honor and corruption, honor never has a chance. And, as if to infuriate the audience even further, Solzhenitsyn reveals how Khomich has a few ideas for the commandant, all of which involve increasing the corruption in the camp and turning the screws harder on the prisoners. These ideas include:

- Issuing the minimum bread guarantee after 101 percent work fulfillment, instead of 100 percent.

- Forcing the workers to over-fulfill their work requirements to have an extra bowl of porridge.

- Not allowing prisoners to receive parcels from the post office unless they have fulfilled 120 percent of their work norms.

- Not allowing men and women to meet unless they have fulfilled 150 percent of their work norms.

- Building a grand house for Commandant Ovchukhov in time for the anniversary of the October Revolution.

Khomich puts it succinctly and smugly: “They’ll realize: either work like an ox or drop dead.”

The Love-Girl and the Innocent is also notable because of how Solzhenitsyn employs its Jewish characters. Prisoners’ Rubin certainly defends the Soviet orthodoxy and the atrocities it entailed. But at least he’s honest, thoughtful, and friendly about it — which certainly counterbalances some of the audience’s negative feelings for him. Love-Girl’s Jews, however, are not only ugly, corrupt, and cruel, they’re stereotypical as well.

Scammell, in summarizing Jewish-Soviet émigré Mark Perakh’s analysis [3] [5] of Solzhenitsyn’s supposed anti-Semitism, writes:

It was in certain of Solzhenitsyn’s other works, however, the Perhakh found the most to criticize, notably in Solzhenitsyn’s early play The Tenderfoot and the Tart. [4] [6] Again, the three Jews in the play — Arnold Gurvich, Boris Khomich, and the bookkeeper named Solomon — were all representatives of evil, but this time grossly and disgustingly so, and Solomon was the very incarnation of the greedy, crafty, influential “court Jew,” manipulating the “simple” Russian camp commandant and oozing guile and corruption. As it happened, Solomon was modeled on the real-life prototype of Isaak Bershader, [5] [7] whom Solzhenitsyn had met at Kaluga Gate and later described at length in volume 3 of The Gulag Archipelago. . . [6] [8]

Solzhenitsyn’s habit during his early period was to include characters based on people he personally knew. In this reviewer’s opinion, he often did so to the detriment of the work itself. Why include such a bewildering array of characters in his already wordy volumes when he could have condensed them into fewer characters for more pithy and forceful results? In some cases, Solzhenitsyn didn’t even bother to change his characters’ names: for example, the fervent Christian Evgeny Divnich (Prisoners) and the Belgian theater director Camille Gontoir (Love-Girl).

Thus, when Solzhenitsyn portrays gulag Jews doing evil things in recognizably Jewish ways, it’s probably because he was being true to what he witnessed in the gulag. It was not Solzhenitsyn’s style to invent a Shylock or Fagin out of thin air just to annoy Jewish people, just as he did not employ anti-Russian stereotypes for the sake of stereotyping. He portrays the Russian thieves in Love-Girl as particularly vile. And the simple-minded, corrupt, and drunken commandant Ovchukhov is no better. There should be no doubt that prisoner Solzhenitsyn had known and dealt with the flesh-and-blood prototypes of many of the characters appearing in his plays.

Regardless, that Solzhenitsyn refused to self-censor his negative Jewish characters while also refusing to include positive ones for the sake of political correctness should tell us something about the ethnocentric line he drew between Russians and Jews. He did not consider Jews as Russians, and he did not care if certain Jews got upset over this. If being labeled an anti-Semite by some is the price to pay for his honesty, his rejection of civic nationalism, and his profound love for his nation and his people, then so be it. [7] [9]

There is quite a bit in The Love-Girl and the Innocent that will resonate with the Right. It was probably unintended by Solzhenitsyn that such a meta-analysis of the Jewish Question would do so as well.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [10] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [11] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Notes

[1] [12] Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Oak and the Calf. New York: Harper & Row, 1975, p. 4.

[2] [13] Michael Scammell, Solzhenitsyn: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1984, p. 330.

[3] [14] Scammell writes of Perakh’s analysis (page 960):

Perakh’s article, a kind of summa of those that had gone before, had appeared in Russian in the émigré magazine Vrennia i My (Time and We) in February 1976 before being published in English in Midstream.

[4] [15] The Love-Girl and the Innocent appears under several titles in English. These include The Tenderfoot and the Tart (as preferred by Scammell), The Greenhorn and the Camp-Whore, and The Paragon and the Paramour. Scammell (on page 217) has this to say about it:

The question of what to call this play in English is problematical. Solzhenitsyn’s Russian title Olen’ I shalashovka is based on camp slang. Olen’ (literally “deer”) means a camp novice, and shalashovka (derived from shalash, meaning a rough hunter’s cabin or bivouac) means a woman prisoner who agrees to sleep with a trusty or with trusties in exchange for food and privileges—not quite a whore, more a tart or tramp. The published English title The Love-Girl and the Innocent seems to me to catch none of this raciness.

[5] [16] I believe that both Scammell and Solzhenitsyn biographer D.M. Thomas overlooked something regarding Solzhenitsyn’s basing of Solomon on Bershader in Love-Girl. It seems to me that Solzhenitsyn based both the bookkeeper Solomon and the doctor Mereshchun on Bershader. The connection with Solomon is based on their shared profession (bookkeeping) and the fact that they were both corrupt, cunning, manipulative trusties in the gulag. But Solomon only appears in two scenes in Love-Girl and has nothing to do with any of the female inmates (Thomas falsely claims that Solomon was “adept at corrupting women prisoners”). The episode with Bershader in The Gulag Archipelago depicts him laying siege to and ultimately corrupting a beautiful and virtuous Russian woman prisoner, which Solomon does not do. Bershader is also described by Solzhenitsyn as “a fat, dirty old stock clerk” who is “nauseating in appearance.” Solzhenitsyn first describes Solomon, on the other hand, as carrying himself “with great dignity” and looking “sharp by camp standards.” Later, he describes Solomon as “very neatly dressed.”

On the other hand, Mereshchun is described as a “fat, thick-set fellow,” which is more in keeping with Bershader’s appearance. Further, Mereshchun enthusiastically corrupts the female inmates. In fact, in his first line of dialogue, he announces: “I cannot sleep without a woman.” After being reminded that he had kicked his last woman out of bed, he responds, “I’d had enough of her, the shit bag.” Clearly, Mereshchun is as revolting as Bershader. He also engages in the same exploitive behavior with women. Could Mereshchun also have been based on Bershader?

In a curious moment in Love-Girl, Solzhenitsyn describes how Mereshchun immediately strikes up a friendship with Khomich the moment he meets him. It was as if they recognized and understood each other without the need of a formal introduction. Could it be that in Solzhenitsyn’s mind they were both Jewish? It’s hard to say. Mereshchun is an odd name, but it could be a Russianized Jewish one, and in the Soviet Union during that time, doctors were disproportionately Jewish. On the other hand, few Russian Jews would be named Timofey. Perhaps Solzhenitsyn meant for this character to have enigmatic origins.

M. Thomas, Alexander Solzhenitsyn: A Century in his Life. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998, p. 492.

[6] [17] Scammell, pp. 960-961.

[7] [18] Thomas (page 490) conveys an astonishingly hysterical example of gentile-bashing from Jewish writer Lev Navrozov who really did not like Solzhenitsyn:

An émigré from 1972, Navrozov denounced Solzhenitsyn’s “xenophobic trash.” He is “a Soviet small-town provincial who doesn’t know any language except his semiliterate Russian and fantasizes in his xenophobic insulation”; August 1914 was as intellectually shabby as The Protocols of the Elders of Zion — but that turn-of-the-century forgery, purporting to show that the Jews were plotting world domination, was actually “superior” in its language to the Solzhenitsyn. . . . His style shows a “comical ineptness”; Navrozov writes that when Ivan Denisovich appeared, he thought its author might develop into a minor novelist, but Khrushchev’s use of him to strike the Stalinists, and his subsequent persecution, made him strut like a bearded Tolstoy, so “this semiliterate provincial, who has finally found his vocation — anti-Semitic hackwork — has been sensationalized into an intellectual colossus. . .

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg