jeudi, 15 février 2024

Les trois moments du péronisme

Les trois moments du péronisme

Enric Ravello Barber

Source: https://euro-sinergias.blogspot.com/2024/02/los-tres-momentos-del-peronismo.html

Nous remercions Pablo Anzaldi, docteur en sciences politiques et militant péroniste, pour sa collaboration à l'élaboration de cet article.

"Pour ce grand Argentin qui a su conquérir la grande masse du peuple en luttant contre le capital".

Marche péroniste.

La naissance d'une nation

En 1816, la province de Río de la Plata, successeur politique de la vice-royauté espagnole de La Plata, proclame son indépendance. Le nouvel État contrôlait effectivement le centre de l'Argentine, la ville de Buenos Aires, l'Uruguay, mais pas de grandes régions de l'Argentine actuelle telles que El Chaco, La Pampa et encore moins la Patagonie. Le général San Martin était le héros de l'indépendance nationale.

À cette époque, la population argentine d'origine espagnole provenait de quatre points : la ville de Mendoza (qui avait été chilienne), le Paraguay, la vice-royauté du Pérou et le noyau fondateur de la ville de Buenos Aires.

En 1833, Juan Manuel de Rosas (illustration) lance la "campagne du désert", qui consiste à contrôler efficacement le centre de l'Argentine, qui comptait jusqu'alors une population indienne peu nombreuse et dispersée. Le projet politique de Rosas ne se limitait pas à l'Argentine, mais à la construction d'une grande puissance biocéanique appelée "Provinces unies du Sud", qui inclurait le sud du Brésil, le Paraguay, la Bolivie, le Chili, l'Uruguay et l'Argentine. Bien entendu, le Royaume-Uni n'a laissé aucune chance à ce projet, allant même jusqu'à manœuvrer pour arracher à l'Argentine ce qui est aujourd'hui l'Uruguay et le rendre "indépendant" en tant qu'État.

En 1862, il adopte le nom définitif de République argentine.

Dans les années 1970, le général Julio Argentino Roca (1879) a mené une seconde et définitive campagne de conquête des régions désertiques et a fait de l'Argentine un État moderne avec toutes ses caractéristiques et ses éléments.

Le fascisme argentin des années 1930 a revendiqué le projet des Provinces unies du Sud et s'est inscrit dans la ligne politique de San Martín, Rosas, dans laquelle Perón se reconnaîtra plus tard.

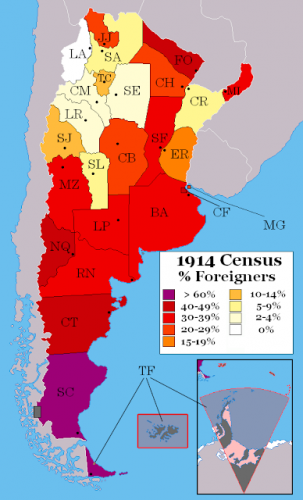

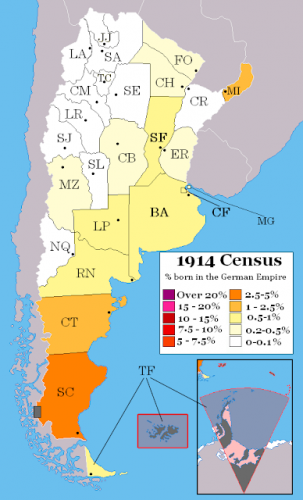

Entre 1880 et 1892, l'Argentine a été la destination d'une énorme immigration européenne qui a changé à jamais la physionomie du pays, le même phénomène s'étant produit au Portugal et dans le sud du Brésil. Cette immigration était principalement composée d'Italiens, suivis d'Espagnols et, dans une moindre mesure, d'Allemands, d'Irlandais, d'Anglais et de Français. Il s'agissait de la deuxième vague européenne en Argentine ; il y en a eu une troisième, beaucoup plus petite, composée principalement d'Allemands, d'Italiens et de Croates exilés suite à la Seconde Guerre mondiale.

Dans ces années-là, l'Argentine était le pays le plus riche du monde. Nous avons assisté à une véritable explosion, non seulement économique, mais aussi culturelle, philosophique et artistique. Pendant quelques années, Buenos Aires est devenue la première ville de la civilisation européenne.

Cependant, un problème structurel s'est posé dès le départ. La distribution des terres agricoles, après les campagnes de conquête des régions désertiques, avait créé une classe sociale, la dénommée "oligarchie" d'origine créole-espagnole, qui se consacrait à l'exportation de produits agricoles et d'élevage à grande échelle, dans un contexte de libre-échange et avec le Royaume-Uni comme principal acheteur.

Pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, au cours de laquelle l'Argentine était neutre, les oligarchies se sont enrichies en exportant de la viande et des céréales vers les marchés européens, mais - et c'est là le défaut endémique de l'histoire économique de l'Argentine - elles n'ont fait aucun effort pour industrialiser le pays. L'excédent économique du secteur primaire n'a pas été investi - comme cela se faisait ailleurs dans le monde - dans la création d'un secteur secondaire puissant qui aurait signifié un saut qualitatif pour l'économie nationale.

Pour mettre fin à la décennie dite infâme, pleine de troubles et de tensions sociales, l'armée a organisé en 1943 un coup d'État militaire, coordonné par ses deux factions internes: les libéraux et les nationalistes. Le gouvernement militaire nomme l'un de ses officiers de l'aile nationaliste, le colonel Juan Domingo Perón, à la tête du ministère du travail et de la guerre, ce qui fait de lui le vice-président de facto. Perón développe une législation à fort contenu social et très favorable au travailleur argentin, ce qui lui vaut de se mettre à dos l'oligarchie en place, elle aussi traditionnellement anglophile, alors que Perón est clairement en faveur des puissances de l'Axe. Un nouveau coup d'État militaire à la fin de l'année 1945 met fin à son gouvernement et Perón est emprisonné.

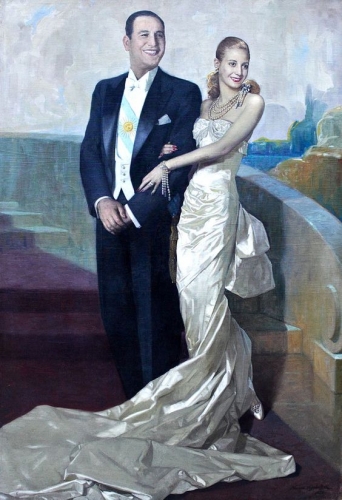

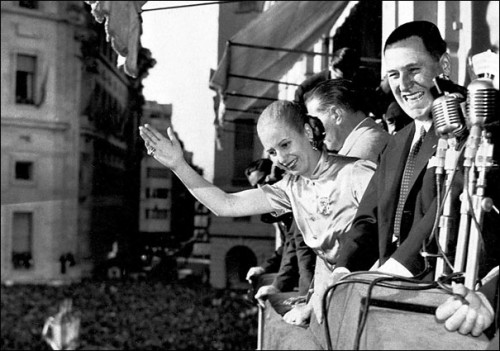

Le péronisme classique 1946-1955

Le 17 octobre 1945, connu dans le calendrier péroniste sous le nom de "Jour de la loyauté", une grande manifestation de travailleurs nationalistes argentins aboutit à la libération de Perón. Après quelques mois de réflexion, Perón décide de se présenter aux élections présidentielles de 1946, son adversaire Branden étant soutenu par toutes les forces anti-péronistes du pays et, de façon claire et publique, par l'ambassade des États-Unis. Le slogan électoral choisi par Perón était clairement "Branden ou moi". Le résultat fut de 53,71 % en faveur du général Perón, inaugurant ce que l'on appelle le "péronisme classique" (1946-55). Cette même année, Perón, veuf depuis 1938, épouse une jeune et courageuse idéaliste, Eva Duarte, ancienne actrice en difficulté.

L'action politique de Perón s'articulait autour de trois points qu'il ne manquait pas de répéter comme base de sa conception politique et de son programme de gouvernement

- la souveraineté politique

- l'indépendance économique

- la justice sociale.

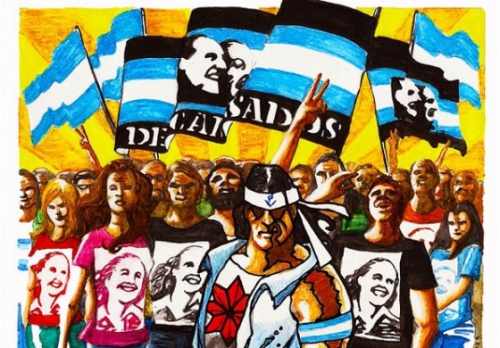

Son épouse, Eva Duarte de Perón, se voit confier les postes de présidente du puissant syndicat national-populaire CGT, de présidente de la Fundación de Ayuda Social, organisation très importante en Argentine à l'époque, et de présidente du Parti des femmes péronistes, poste qui n'est guère plus que symbolique. Son rôle social et politique exceptionnel dans la défense des classes les plus défavorisées, "los descamisados", et sa confrontation avec l'armée, qu'elle préconisait de remplacer par une milice nationale-populaire armée, lui ont valu l'amour et le dévouement de la majorité des Argentins, qui l'appelaient affectueusement Evita, mais aussi l'inimitié de l'oligarchie réactionnaire, qui s'est déchaînée contre son mari.

L'Argentine pleure la mort d'Evita en 1952. La distance de l'Église à l'égard de Perón s'intensifie; elle ne tolère pas le "culte civique" d'Evita, qui, rappelons-le, a joué un rôle décisif dans l'approbation de la loi sur le divorce en Argentine. En 1954, des actes de violence commis par les "commandos civils" ont commencé à éclater dans toute l'Argentine et la synergie entre l'Église et les éléments réactionnaires et libéraux contre Perón s'est intensifiée. Une série de coups d'État échouent et Perón, qui bénéficie encore du soutien de la majorité, est conscient du grand risque d'une guerre civile sanglante. Pour éviter cela, Perón démissionne et part en exil; les conditions, qu'il avait posées, de respecter son héritage politique ne sont pas suivies d'effet par la nouvelle junte militaire libérale au pouvoir.

L'exil 1956-1973

Son exil marque le début de la deuxième phase du péronisme, qui s'étend de 1955 à son retour triomphal en 1973.

Perón s'exile d'abord au Paraguay, où il est accueilli par son ami Stroessner, mais la proximité de l'Argentine et la connaissance de tentatives d'assassinat par le nouveau gouvernement de la Casa Rosada l'obligent à choisir une autre destination: la République dominicaine. Il y rencontre Isabel, qui deviendra sa troisième épouse et la première femme présidente de la République argentine. Après un bref séjour dans le Venezuela de Marcos Pérez, il s'installe en Espagne en 1960. Franco l'autorise à vivre en Espagne, mais sans jouer aucun rôle politique, ce que Perón fait depuis sa résidence de Puerta de Hierro (Madrid).

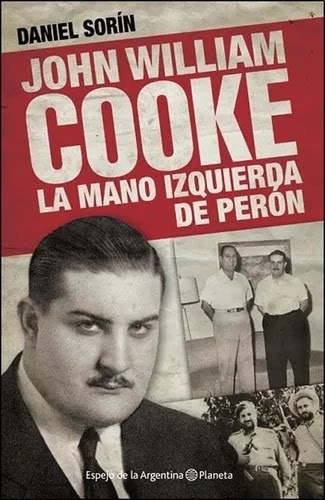

Perón laisse le commandement de la résistance péroniste en Argentine à l'un de ses cadres les plus courageux et les mieux préparés intellectuellement, John William Cooke, un Argentin d'origine irlandaise. Et c'est là que commence un sérieux problème. Cooke a voyagé à Cuba, a été fasciné par la révolution castriste et s'est déclaré marxiste-léniniste, affirmant que le péronisme devait se muer et réaliser la même révolution marxiste en Argentine, et est également devenu un ami personnel du philosophe français Sartre, pour lequel Perón éprouvait un profond mépris. Perón rejeta catégoriquement cette approche, démit Cooke de ses fonctions et le remplaça par le social-nationaliste Alberto Brito Lima (photo, ci-dessous).

La dérive de Cooke préfigure le grand problème interne auquel Perón et le péronisme seront confrontés dans les années suivantes. La naissance du mouvement montonero. Il faut être clair et concret. Les Montoneros étaient une organisation criminelle marxiste-léniniste qui prétendait défendre un "péronisme sans Perón" qui n'était en réalité rien d'autre que la stratégie cubaine de création d'une révolution communiste en Argentine. Les Montoneros ont affronté Perón et ont été objectivement alliés aux forces antinationales et antisociales opposées au général. La tension entre Perón et ses fidèles nationaux-populaires et les Montoneros marxistes s'accroît rapidement, un fossé infranchissable les sépare. Les affrontements entre les Montoneros et les organisations nationales-péronistes: la Garde de fer, la Concentration universitaire argentine, le Commandement organisateur et les Montoneros-Lealtad (scission fidèle au général), prennent des allures de guerre civile.

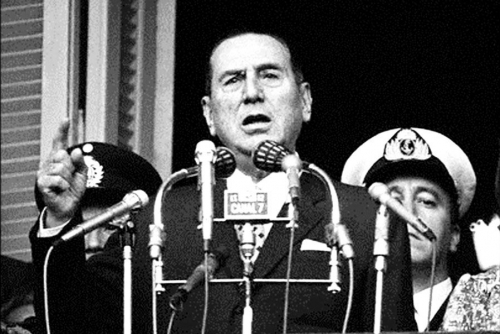

Du retour triomphal au coup d'État des "gorillas" (1973-1976)

Le 20 juin 1973, Perón fait un retour triomphal à Buenos Aires. Avant de quitter Madrid pour retourner à Buenos Aires, il ordonne que l'estrade où il prononcera son premier discours sur le sol argentin soit occupée exclusivement par des partisans péronistes et il oppose son veto à la présence des Montoneros. Le même jour, les Montoneros tentent de prendre d'assaut la scène pour manipuler la présence de Perón. D'importants affrontements armés opposent les Montoneros aux milices nationales-populaires péronistes, faisant 69 morts et 135 blessés, en grande majorité des Montoneros.

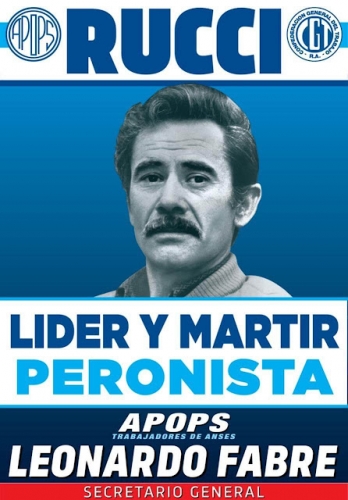

Pour se venger, les Montoneros assassinent José Ignacio Rucci, le principal dirigeant du syndicat péroniste CGT et la personne en qui le général Perón avait confiance pour poursuivre son travail social et politique national avec sa troisième épouse, Isabel de Perón. Lors des élections présidentielles de 1974, Isabel Martínez de Perón (photo), soutenue par son mari, a remporté 62% des voix et est devenue la première femme présidente de l'Argentine. L'Argentine connaît alors des années difficiles et des violences éclatent. En 1974, Perón signe un document appelé Acta reservada dans lequel il ordonne de combattre les organisations marxistes par tous les moyens nécessaires, en faisant référence aux Montoneros et à l'ERP (1).

Perón meurt le 1er juillet 1974 et l'instabilité et la violence deviennent insupportables. En 1976, le secteur libéral de l'armée - les Gorillas (2) - a organisé un coup d'État et la junte militaire a été formée. La Junte des Gorillas a initié une forte répression anti-péroniste qui ne s'est achevée qu'avec la fin de la dictature en 1981.

Notes:

(1) Ejercito Revolucionario del Pueblo, une organisation terroriste trotskiste qui entretenait de bonnes relations avec les Montoneros.

(2). Gorilla : militaire anti-péroniste, libéral et atlantiste.

20:09 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : juan peron, peronisme, argentine, amérique latine, amérique du sud, amérique ibérique, histoire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 03 novembre 2023

La validité et l'efficacité de la pensée de Perón

La validité et l'efficacité de la pensée de Perón

Antonio Rougier

Source: https://geoestrategia.es/noticia/41680/opinion/la-vigenci...

Comme la vie le veut, et parce que les âmes sœurs se rencontrent aussi, je suis entré en contact via Facebook avec Pedro Jubera García de Madrid. Et, partant de conceptions apparemment différentes (socialisme espagnol et justicialisme argentin), nous nous sommes mis d'accord sur les fondamentaux : le respect de la dignité humaine et la lutte pour la justice sociale.

Sur cette base, il me demande d'essayer d'apporter des concepts sur "la validité et l'efficacité de la pensée de Perón" (dans un bref résumé) afin de contribuer à sa clarification dans les milieux espagnols à travers la prestigieuse REVISTA GEOESTRATEGIA.

Ma gratitude est suprême.

Péronisme ou justicialisme

Commençons par clarifier le "nom". Il faut savoir que le mot Justicialismo est synonyme de "doctrine péroniste". Parmi les idées et les concepts qui fondent le projet politique, le "péronisme" a été la première concrétisation de ces "idées ou doctrine" au cours de la vie du général Juan Domingo Perón.

Cela signifie qu'il peut y avoir d'autres "réalisations" de la doctrine péroniste, des idées de Perón, du justicialisme, comme ce fut le cas en Argentine, selon mon concept, du kirchnerisme et de l'actuel "multilatéralisme" en tant qu'expression de la "troisième position" proposée par Perón.

La coïncidence entre la "doctrine péroniste" et le "justicialisme" se trouve dans la définition même de la doctrine péroniste :

"La Doctrine péroniste ou Justicialisme, qui a pour but suprême d'atteindre le bonheur du Peuple et la grandeur de la Nation, au moyen de la Justice sociale, de l'Indépendance économique et de la Souveraineté politique, en harmonisant les valeurs matérielles avec les valeurs spirituelles, et les droits de l'individu avec les droits de la société".

Et sa réalisation, Perón l'explique ainsi, en parlant de sa "troisième position" le 1er décembre 1952 :

"Le gouvernement des nations peut se réaliser de différentes manières ; mais toutes, au cours de l'histoire, ont oscillé comme un pendule entre l'individualisme et le collectivisme. Nous pensons qu'entre ces deux extrêmes, il existe une troisième position, plus stable et permanente, et c'est sur cette troisième position que nous avons fondé toute notre doctrine, dont les principes constituent le Justicialisme et dont la réalisation est le Péronisme".

Nous essaierons donc désormais de partager avec vous ce qu'est le Justicialisme, dont la première "réalisation" a été le Péronisme. Et qui a été pensé comme une proposition universelle, comme nous essaierons de le justifier.

Le Justicialisme est un Mouvement National

Qu'est-ce que cela signifie ? Cela signifie que toute la proposition politique de Perón, dans ses idées et ses réalisations, s'adressait et s'adresse toujours "au peuple argentin dans son ensemble". Par conséquent, le Justicialisme n'est pas un "parti politique", même s'il prend cette forme pour pouvoir participer à la structure "démocratique" nationale et internationale actuelle.

Parce que Perón a pris l'Argentine, l'ensemble du peuple argentin comme une unité, comme un corps, comme une organisation unique. Et pour Perón, toute organisation, et donc l'Argentine, doit comporter deux éléments essentiels :

- l'organisation spirituelle, constituée par l'ensemble des idées et surtout par l'objectif qui "unit" les membres de toute organisation. Idées ou objectifs qui visent à unir les membres du Mouvement Justicialiste National.

- L'organisation matérielle, constituée par la forme et la manière de réaliser ces idées, cette finalité, que Perón appelle "formes d'exécution".

Pour Perón, l'instrument de l'organisation spirituelle est la "doctrine". Réaliser ce qu'il appelle "l'unité de conception", l'unité d'idées, l'unité d'objectifs au sein du peuple dans son ensemble.

Pour que le peuple nous accompagne librement et volontairement dans la réalisation de ces idées, de cette doctrine. Réaliser "l'unité d'action". Une tâche qui implique nécessairement une occupation constante pour "transmettre" ces idées, cette Doctrine.

Le but premier pour atteindre le but suprême

Le but premier des idées, d'une "doctrine nationale" était de réaliser ce qu'il appelait "l'unité nationale" le 1er mai 1950 avec ces concepts.

"Pour que notre peuple adopte notre idéologie et réalise la coïncidence essentielle pour atteindre notre objectif premier d'unité nationale, il était nécessaire d'abattre toutes les barrières de séparation entre le peuple et ses gouvernants et entre les différents groupes sociaux d'un même peuple, et de faire en sorte que chaque Argentin se sente maître de son propre pays. C'est pourquoi nous avons lancé le grand objectif de notre mouvement : la justice sociale".

La doctrine n'est pas née d'une réflexion de bureau mais d'un "processus" permanent de contact et de dialogue avec les travailleurs en particulier.

Ce processus peut se résumer ainsi : le premier objectif de Perón était la "justice sociale" : que chaque Argentin vive un peu plus heureux, un peu plus dignement que jusqu'alors, comme le veut le principe de la "dignité humaine".

Lorsqu'il a essayé de mettre cela en pratique, il a constaté que presque tous les biens du pays se trouvaient dans des mains étrangères : la Banque centrale, les chemins de fer, les transports terrestres et maritimes, etc. Il lui faut donc réaliser l'"indépendance économique" et la "souveraineté politique" sans lesquelles cette justice sociale est impossible.

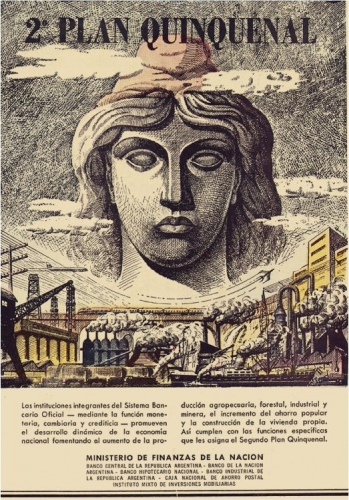

La réalisation de cette "justice sociale" par le biais de l'"indépendance économique" et de la "souveraineté politique" a pris toute la durée du premier gouvernement : de 1946 à 1951, et il l'a réalisée par le biais du premier plan quinquennal.

Une fois la "justice sociale" réalisée avec succès au cours de cette période et en préparation du deuxième plan quinquennal, il définit "la doctrine péroniste ou justicialisme" comme le troisième article de la loi "nationale" 14.184 du deuxième plan quinquennal :

"Aux fins d'une interprétation correcte et d'une exécution efficace de la présente loi, la "doctrine nationale", adoptée par le peuple argentin, est définie comme la doctrine péroniste ou le justicialisme, qui a pour objet:

- L'objectif suprême est d'atteindre le bonheur du peuple et la grandeur de la nation,

- par la justice sociale, l'indépendance économique et la souveraineté politique,

- en harmonisant les valeurs matérielles avec les valeurs spirituelles, et les droits de l'individu avec les droits de la société.

L'objectif premier de "l'unité nationale" pour atteindre l'objectif suprême du "bonheur du peuple et de la grandeur de la nation".

Tous ces concepts proposés dans l'histoire, en tant que projet politique, n'ont été proposés par le Justicialisme qu'avec cette clarté et sont parfaitement réalisables aujourd'hui dans n'importe quelle partie du monde.

Dans n'importe quel pays du monde, il est possible de former un Mouvement qui vise le "tout" du Peuple. Il est "national".

Il a pour but premier l'unité nationale.

Son but suprême doit être "le bonheur de son peuple et la grandeur de sa nation".

Qu'il réalise ce bonheur et cette grandeur par la justice sociale, l'indépendance économique et la souveraineté politique.

En cherchant toujours, en toutes choses, à harmoniser les valeurs matérielles avec les valeurs spirituelles et les droits de l'individu avec ceux de la société.

Bien sûr, en essayant de comprendre, par la réflexion et l'étude, quel est le sens et la signification que le Justicialisme donne à chacun de ces concepts.

Un sens et une signification que l'on retrouve dans le plan de formation mis en œuvre par Perón à travers l'École supérieure péroniste et les Écoles syndicales pour parvenir à l'"élévation culturelle" permanente de l'ensemble du peuple. Vous pouvez consulter ce plan sur le site www.escuelasuperiorperonista.com

Et dont la première et synthétique explication se trouve dans ce résumé.

APERÇU GÉNÉRAL DE LA DOCTRINE PÉRONISTE OU JUSTICIALISME:

1 - Objectifs de la doctrine.

1.1 - Immédiat : l'unité nationale. 1.2.

1.2 - Ultime : bonheur du peuple et grandeur de la nation.

2.- L'homme, la femme, l'être humain est une dignité (c'est le principe philosophique fondamental).

2.1 - Est un principe et une fin en soi (a des valeurs individuelles).

2.2 - Elle a une fonction sociale (valeurs sociales).

2.3 - Elle a des valeurs spirituelles (c'est l'harmonie de la matière et de l'esprit).

3.- La justice sociale (c'est le principe sociologique fondamental), qui implique :

3.1 - Elever la culture sociale (sociologie de la culture)

3.2 - Dignifier le travail (sociologie du travailleur, de la famille, du peuple, de l'Etat).

3.3 - Humaniser le capital (sociologie économique).

4.- L'indépendance économique (principe économique fondamental) signifie:

4.1 - Récupérer le patrimoine national (première étape).

4.2 - Réactiver l'économie (mettre le capital au service de l'économie).

4.3 - Répartir équitablement les richesses (mettre l'économie au service de la fonction sociale).

5.- La souveraineté politique (c'est le principe politique fondamental) qui signifie :

5.1 - Respecter la souveraineté des citoyens (droits des citoyens)

5.2.- Respecter la souveraineté du peuple (démocratie).

5.3 - Respecter la souveraineté de la Nation (autodétermination des Peuples).

Sans jamais oublier le fondement spirituel du Justicialisme et ses conséquences, exprimé dans ce texte de l'Histoire du Péronisme d'Eva Perón.

"Les doctrines triomphent, dans ce monde, selon la dose d'amour infusée dans leur esprit. C'est pourquoi le Justicialisme, qui commence par affirmer qu'il est une doctrine d'amour et finit par dire que l'amour est la seule chose qui construit, triomphera.

Plus la doctrine est grande, plus elle est niée, plus elle est combattue. C'est pourquoi nous, les Justiciers, nous devons être fiers de savoir que les incapables, les vendus, les vénaux, ceux qui ne sont pas dans les intérêts patriotiques, la combattent de l'intérieur et de l'extérieur. Notre doctrine doit être bien grande quand elle est ainsi redoutée, combattue, détruite".

"Son efficacité et sa permanence dans le temps (1945-2023), comme le dit une chanson populaire : "malgré les bombes, les fusillades, les camarades morts, les disparus, ils ne nous ont pas vaincus". Et ils ne nous vaincront pas parce que le Justicialisme est une doctrine d'amour, parce que l'amour est la seule chose qui construit. Ce n'est qu'avec l'amour que l'on peut construire le bonheur d'un peuple et la grandeur d'une nation.

Et l'amour ne peut être tué. Il ne meurt jamais".

22:36 Publié dans Histoire, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : argentine, juan peron, evita peron, justicialisme, peronisme, amérique latine, amérique du sud, amérique ibérique, théorie politique, philosophie politique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 05 janvier 2017

Nacional Justicialismo

Nacional Justicialismo

Ex: http://tercerapn.blogspot.com

Bombardeo a Plaza de Mayo

Bombardeo a Plaza de Mayo Las Veinte Verdades Peronistas

Las Veinte Verdades Peronistas- La verdadera democracia es aquella donde el gobierno hace lo que el pueblo quiere y defiende un solo interés: el del pueblo.

- El Peronismo es esencialmente popular. Todo círculo político es antipopular, y por lo tanto, no es peronista.

- El peronista trabaja para el Movimiento. El que en su nombre sirve a un círculo, o a un caudillo, lo es sólo de nombre.

- No existe para el Peronismo más que una sola clase de hombres: los que trabajan.

- En la Nueva Argentina el trabajo es un derecho que crea la dignidad del hombre y es un deber, porque es justo que cada uno produzca por lo menos lo que consume.

- Para un Peronista de bien, no puede haber nada mejor que otro Peronista.

- Ningún Peronista debe sentirse más de lo que es, ni menos de lo que debe ser. Cuando un Peronista comienza a sentirse más de lo que es, empieza a convertirse en oligarca.

- En la acción política la escala de valores de todo peronista es la siguiente: primero la Patria, después el Movimiento, y luego los Hombres.

- La política no es para nosotros un fin, sino sólo el medio para el bien de la Patria, que es la felicidad de sus hijos y la grandeza nacional.

- Los dos brazos del Peronismo son la Justicia Social y la Ayuda Social. Con ellos damos al Pueblo un abrazo de justicia y de amor.

- El Peronismo anhela la unidad nacional y no la lucha. Desea héroes pero no mártires.

- En la Nueva Argentina los únicos privilegiados son los niños.

- Un gobierno sin doctrina es un cuerpo sin alma. Por eso el Peronismo tiene su propia doctrina política, económica y social: el Justicialismo.

- El Justicialismo es una nueva filosofía de vida simple, práctica, popular, profundamente cristiana y profundamente humanista.

- Como doctrina política, el Justicialismo realiza el equilibrio del derecho del individuo con la comunidad.

- Como doctrina económica, el Justicialismo realiza la economía social, poniendo el capital al servicio de la economía y ésta al servicio del bienestar social.

- Como doctrina social, el Justicialismo realiza la Justicia Social, que da a cada persona su derecho en función social.

- Queremos una Argentina socialmente justa, económicamente libre, y políticamente soberana.

- Constituimos un gobierno centralizado, un Estado organizado y un pueblo libre.

- En esta tierra lo mejor que tenemos es el Pueblo.

12:37 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : péronisme, justicialisme, argentine, juan peron, evita peron, amérique latine, amérique du sud, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 29 décembre 2014

Kerry Bolton’s Perón & Perónism

Kerry Bolton’s Perón & Perónism

By Eugène Montsalvat

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

Kerry Bolton

Perón and Perónism

London: Black House Publishing, 2014

Perón and Perónism is an excellent resource on the political thought of Argentina’s three-time president Juan Domingo Perón. It places him firmly among the elite ranks of Third Position thinkers. His doctrine of Justicalism and his geopolitical agenda of resistance to both American and Soviet domination of Latin America have demonstrated enduring relevance. Influenced by Aristotle’s conception of man as a social being and the social teachings of the Catholic Church, Perón proved to be an insightful political philosopher, developing a unique interpretation of National Syndicalism that guided his Justicalist Party. While his career was marked by turmoil, he pursued an agenda of the social justice, seeking the empowerment of the nation’s working classes as a necessary step towards the spiritual transformation of the country. Perón’s example stands as a beacon to those who seek the liberation of man from the bondage of materialism, and the liberation of the nation from foreign domination.

Perón and Perónism is an excellent resource on the political thought of Argentina’s three-time president Juan Domingo Perón. It places him firmly among the elite ranks of Third Position thinkers. His doctrine of Justicalism and his geopolitical agenda of resistance to both American and Soviet domination of Latin America have demonstrated enduring relevance. Influenced by Aristotle’s conception of man as a social being and the social teachings of the Catholic Church, Perón proved to be an insightful political philosopher, developing a unique interpretation of National Syndicalism that guided his Justicalist Party. While his career was marked by turmoil, he pursued an agenda of the social justice, seeking the empowerment of the nation’s working classes as a necessary step towards the spiritual transformation of the country. Perón’s example stands as a beacon to those who seek the liberation of man from the bondage of materialism, and the liberation of the nation from foreign domination.

Juan Domingo Perón was born on the 8th of October 1895 and graduated from the Colegio Militar, entering the military as a sublieutenant. He later attended the Escuela Superior de Guerra, and became a professor of military history at the War College. His mission to Europe in 1939 proved to be a formative experience on his political consciousness. He was inspired by Mussolini’s rejection of both American capitalism and Soviet communism, stating that, “When faced with a world divided by two imperialisms, the Italians responded: we are on neither side. We represent a third position between Soviet socialism and Yankee imperialism.” Perón became a member of the Group of United Officers (GOU) that overthrew in the Argentine government in 1943.

The GOU was menaced by American pressure due to Argentina’s neutrality in the Second World War and its pro-Axis government. An attempt to buy arms from Germany resulted in American ships being sent to patrol near the mouth of the River Plate and the refusal of American banks to transfer Argentine funds. In response Argentina severed relations with the Axis, but that did not prevent an American embargo.

Within the GOU government, Perón eventually became Vice President, Minister of War, Secretary of Labor and Social Reform, and head of the Post-War Council. He became known as a champion of labor, supporting unionization, social security, and paid vacations, meeting populist radio actress Eva Duarte, his second wife, in the process. However, Perón’s success attracted suspicion from others in the government and General Eduardo Avales forced him to resign his posts and had him imprisoned on October 10th 1945.

However, the forced resignation and imprisonment of Perón triggered a fateful sequence of events that were eventually commemorated in Justicalist ideology on “Loyalty Day.” In response to Perón’s imprisonment, Eva Duarte rallied his supporters in labor, and the CGT labor union declared a general strike. Workers mobbed the labor department in support of the profit-sharing law Perón sponsored. They ran the police gauntlet to flood the plaza in front of the presidential palace. Perón was released and declared his candidacy for the presidency before throngs of supporters from the blacony of the presidential palace on October 17th, now celebrated as “Loyalty Day” by Perónists.

The 1946 election was essentially a struggle between Perón and the US-backed oligarchy of Argentina. Perónist posters asked “Braden or Perón?,” referencing the American ambassador Spruille Braden. The United States attempted to demonize Perón, accusing him of collaboration with the Axis in the Second World War and claiming that Perón planned to institute a totalitarian state, with tactics reminiscent of latter days attempts to paint any leader who doesn’t toe the American line as a rogue who hates freedom. The document summarizing America’s vendetta against Perón was adopted by the anti-Perón Unión Democrática, which comprised both oligarchs and some communist elements. The willingness of the opposition to act as lapdogs for Yankee imperialism only strengthened Perón’s support and he won the election of February 24th 1946.

Perón’s base of support came from the working classes, nicknamed descamisados, the shirtless. The doctrine that drew their support, Justicialism, is a type of National Syndicalism, devoted to the achievement of social justice within the context of the nation as an organic social unit. Perónist constitutional thinker Arturo Sampay defined social justice as “that which orders the interrelationships of social groups, professional groups, and classes with individual obligations, moving everyone to give to other in participation in the general welfare.”

The achievement of social justice would necessitate the elimination of artificial distinctions in society, such as economic classes and political parties. Instead every sector of society would be organized into its own syndicate, essentially the equivalent of the medieval guilds that were destroyed in the French Revolution. Perón saw in the guilds of the past an alternative to the capitalist system of wage labor, providing a social dimension to labor. The worker was a craftsman, integrated into the wider world, instead of a mere cog for the capitalists. Perón saw capitalism as the exploitation of producers by the owners of the means of production:

Capitalism refines and generalizes the system of wages throughout the production area, or the exploitation of the poor by the wealthy. This gives birth to new economic and social classes. For one the holders of the means of production – machinery, art, tools, workshops, that is – the capitalist bourgeoisie; on the other hand, employees or the proletariat to deliver the first fruits of their creative efforts.

Man thus becomes a number, without the union corporation, without professional privileges, without the protection and representation of his Estate. The political party establishes the non-functional structure that serves the bourgeoisie in power.

Justicialism sought to undo this distortion of the natural order caused by capitalism. To achieve this, Perón gave a special position to labor unions as leading actors, seeing them as the basis for the syndicates he envisioned to represent each function in society. He sought to transform enterprises into cooperatives where profits where shared between all the producers. Their governing bodies would be the syndicates, who served the national interest, rather than capitalists who served profit alone. Private property would still exist under Justicalism, but it would be distributed so as to encourage production, the ownership of property yoked to the greater good of the nation. He stated that every Argentine should have his own property, yet he believed that factories and businesses should belong to those who work in them. Industries crucial to the maintenance of national sovereignty and economic independence like banking and mining would belong to the state, in order to prevent foreign capitalists from seizing the vitals of the Argentine nation. Perón’s government nationalized the banks, the railways, the airlines, the port of Buenos Aires, and he established the state run oil and gas industry. Much like the Catholic social doctrine of Distributism, Justicialism did not seek to eliminate private property but to give each man what was necessary to produce for the greater good of society.

For Perón work would become an ideal higher than mere bread-winning. It is a spiritual calling that links the achievements of an individual to the achievements of the past and his people. It is a tool of individual and social growth. Work should be mandatory, with everyone striving to contribute, however at the same time the dignity of the worker must be enshrined by law. As such the government enacted a “Workers’ Bill of Rights.” It affirmed the right to a fair wage, unionization, education, safe working conditions, healthcare, adequate healthcare and housing, and social security. However, unlike modern social democrats who see the welfare state as simply providing for man’s materialistic needs, Perón saw it as step towards the spiritual development of the people.

Citing Aristotle’s belief that man was a social being who actualized himself through participation in society, he saw eliminating material hardships as the first step in developing the virtue of the people. Through communal organization the ideal of a better humanity could be reached. In a further tribute the classical ideals of communal self-improvement, Perón emphasized the importance of physical exercise, stating that:

the educated man must have developed to being harmonious and balanced in both his intelligence and his soul and his body. . . . We want intelligence to be in the service of a good soul and a strong man. In this we are not inventing anything, we are going back to the Greeks who were able to establish that perfect balance in their men in the most glorious period of its history.

Through sports the youth would develop civic virtue, training men for a life of service. One of the administrations involved in implementing this task was the Fundación Eva Perón.

The Fundación Eva Perón was a social aid agency named for Juan Domingo’s wife, Eva, who played a leading role in it. Established in 1948, its goals included giving scholarships and training to the poor, constructing housing, schools, hospitals, and other public buildings, and engaging in work for the common good. Eva Perón termed this Social Aid, a form of collective self help, explicitly rejecting the idea of charity, saying:

The donations, which I receive every day, sent into the Fund by workmen, prove that the poor are those who are ready to do the most to help the poor. That is why I have always been opposed to charity. Charity satisfies the person who dispenses it. Social Aid satisfies the people themselves, inasmuch as they make it effective. Charity is degrading while Social Aid ennobles. Give us Social Aid, because it implies something fair and just. Out with charity!

Among the successful Social Aid projects of the Fundación Eva Perón were the training of nurses, the establishment of large hospitals termed policlincs, the establishment of mobile health care trains, and the construction of homes for the elderly, students, and children.

Given the active and outspoken role Eva Perón played in the Justicalist movement, one would think she would be embraced as a feminist icon. However, Evita herself disdained such characterizations and affirmed the necessity of differing roles for the sexes. She said:

Every day thousands of women forsake the feminine camp and begin to live like men. They work like them. They prefer, like them, the street to the home. They substitute for men everywhere. Is this “feminism”? I think, rather, that is must be the “masculinization” of our sex.

And I wonder if all this change has solved our problem? But no, all the old ills continue rampant, and new ones too, appear. The number of women who look down upon the occupation of homemaking increases every day. And yet that is what we are born for. We feel we are born for the home, and home is too great a burden for our shoulders. Then we give up the home . . . go out to find a solution . . . feel that the answer lies in obtaining economic independence and working somewhere. But does that makes us equal to men? No! We are not like them! We feel the need of giving rather than receiving. Can’t we work for anything else than earning wages like men?

The Justicialist creed of social justice supported the family as the basis of society. Juan Perón stated, “Man is created in the image and likeness of God. But this transcendent unity is by nature a social being: born of a family, man and woman, as the first basic social group and the parents provide essential care, without which man cannot survive. This develops within a broader community that was forming along centuries and, therefore, provides the imprint of a civilization and a historical culture. It develops into productive, cultural, professional and other intermediate communities.” In providing social welfare Perón was not replacing the family with the state, but ensuring that a man could afford to feed his family, to maintain their well-being so as to encourage their social development within the nation. By tending this seed of the nation, Justicialism would ensure the growth of virtue among the citizens.

A further part of Perón’s social agenda was the destruction of usury. Perón held that the creation of money should serve a social purpose, not profit the bankers. His government nationalized the banks. Perónist Arturo Sampay said, “Whoever gives the orders on credit and the expansion or contraction of the money supply, controls the development of the country.” As a basic principle of national sovereignty the nation cannot be indebted to private bankers or foreign investors. If a bank is foreign owned or invested in foreign trade, it serves the interests of the foreigners, not the country. Perón termed the banks sepoys, referring to Indian troops who served British imperialism. Perón’s government used the National Mortgage Bank to provide money for public housing at low interest rates, which allow many people to own homes, leading to a more the equitable distribution of property. Perón believed that the money supply should not be manipulated by bankers for profit, but increased or decreased at a rate tied to the work done by the members of the nation. Money was not tied to vague financial mechanisms, but real labor and production. Perón wrote:

But in the domestic, social economy our doctrine states that the currency is a public service that increases or decreases, is valued or devalued in direct proportion to the wealth produced by the work of the Nation.

Money is for us one effective support of real wealth that is created by labor. That is, the value of gold is based on our work as Argentines. It is not valued at weight, as in other currencies based on gold, but by the amount of welfare that can be funded by working men. Neither the dollar or gold are absolute values, and happily we broke in time with all the dogmas of capitalism and we have no reason to repent. It happens, however, as to those who accept willingly or unwillingly the orders or suggestions of capitalism, that the fate of their currencies is tied to what is minted or printed in the Metropolis, encrypting all the wealth of a country circulating with strong currencies, but without producing anything other than currency trade or speculation. We despise, perhaps a bit, the value of hard currencies and choose to create instead the currency of work. Maybe this is a little harder than what you earn speculating, but there are fewer variables in the global money game.

Gentleman, in terms of “social economy,” it is necessary to establish definitely: The only currency that applies to us is the real work and production that are born on the job.

Perón’s rejection of international monetary conventions attracted the enmity of the foreign powers intent on using Argentina’s wealth for their own gain. Argentina explicitly rejected the International Monetary Fund. In foreign trade, instead of pursuing exchanges through currency Argentina sought to swap foreign commodities for their commodities, directly bartering goods instead of money. Perón’s refusal to abide by the demands the United States’ global plutocracy drew America’s ire. In 1948 the US excluded Argentine exports from the Marshall Plan zone. Attempts to resolve their differences where stymied by Congress’ refusal to accept the role of the Argentina Institute for the Promotion of Trade (IAPI), which sold Argentine commodities on the international market and subsidized their national production. This autarchic economic planning mechanism flew in the face of America’s pursuit of globalization. If Argentina refused to give dollars, instead seeking to barter goods, the US demanded that they give concessions to American companies, allowing foreign industry to compete with national ones Perón was devoted to developing. America’s assault on Argentina’s economy was a grievous blow to the Perón government, and he began his second term in 1952 with a $500 million trade deficit. That year saw meat shortages and power failures, and while the economy recovered somewhat from 1953 to 1955, the stage was set for the downfall of the regime. In 1955, after a failed coup attempt on September 3rd, a successful coup attempt was launched by the Navy on the 16th. Perón left for Paraguay on the 20th and eventually settled in Spain. The fall of Perón’s government led to the sale of national assets to US corporations, by 1962 production had dropped, the trade deficit had massively increased, and the price of of food increased by 750%.

While his attempts to resist Yankee domination failed and led to the end of his second term, Perón attempted to develop a geopolitical doctrine that would prevent Latin America from falling prey to the predations of the US. He proposed a formation of a geopolitical bloc to resist the Superpowers intent on controlling Latin America, effectively making him an advocate of the multi-polar world envisioned by Russian geopolitical theorist Alexander Dugin fifty years later. In 1951 he articulated his goal:

The sign of the Southern Cross can be the symbol of triumph of the numina of the America of the Southern Hemisphere. Neither Argentina, nor Brazil, nor Chile can, by themselves, dream of the economic unity indispensable to face a destiny of greatness. United, however, they form a most formidable unit, astride the two oceans of modern civilization. Thus Latin-American unity could be attempted from here, with a multifaceted operative base and unstoppable initial drive.

On this basis, the South American Confederation can be built northward, joining in that union all the peoples of Latin roots. How? It can come easily, if we are really set to do it.

We know that these ideas will not please the imperialists who divide and conquer. United we will be unconquerable; separate defenseless. If we are not equal to our mission, men and nations will suffer the fate of the mediocre. Fortune will offer us her hand. May God wish we know to take hold of it. Every man and every nation has its hour of destiny. This is the hour of the Latin people.

Perón made overtures to the governments of Brazil and Chile to pursue regional cooperation. In 1953, Chile’s president Carlos Ibáñez del Campo, a friend of Perón, signed an agreement with Argentina to reduce tariffs, facilitate bilateral trade, and establish a joint council on relations between the two nations. Similarly, he pursued integration with Brazil, led by the corporatist Getulio Vargas. While Vargas had been supported in the presidential election by Argentina, he was constrained by pro-American forces in Brazil’s government and a general reliance on American trade. Any chance of integration faded with the suicide of Vargas in the face of an impending revolt.

Perón’s geopolitical relations also extended to Europeans who sought to break free from the American domination that had descended upon the continent in the wake of the Second World War. Like Latin America, Europe had been subjected to Yankee imperialism. Perón met several times with Oswald Mosley, the former leader of the British Union of Fascists, who advocated the formation of an integrated European bloc to reject American and Soviet domination after the World War II, analogous to the Latin American continental unity that Perón supported. Mosley visited Argentina in 1950 and his views may have shaped the development Perón’s geopolitical vision. From exile Perón wrote to Mosley, “I see now we have friends in common whom I greatly value, something which makes me reciprocate even more your expressions of solidarity . . . I offer my best wishes and a warm embrace.”

Among the mutual friends of Mosley and Perón was Jean Thiriart, whom he met through German commando Otto Skorzeny. Like Mosley, Thiriart advocated the formation of a unified Europe to combat American imperialism, though on a more militant level. He saw Latin America, which had been engaged in struggles against American domination for far longer than Europe as an ally to his cause. Perón responded positively to Thiriart’s ideas writing, “A united Europe would count a population of nearly 500 million, The South American continent already has more than 250 million. Such blocs would be respected and effectively oppose the enslavement to imperialism which is the lot of a weak and divided country.” Thus a fundamental alliance between Third World Third Positionism and European Third Positionism existed.

From exile in 1972, Perón addressed the situation of the Third World, decrying the social and ecological destruction wrought by international capitalism. He made several recommendations in that speech regarding the necessary steps they must take to ensure social justice in their nations:

- We protect our natural resources tooth and nail from the voracity of the international monopolies that seek to feed a nonsensical type of industrialization and development in high tech sectors with market-driven economies. You cannot cause a massive increase in food production in the Third World without parallel development of industries. So each gram of raw material taken away today equates in the Third World countries with kilos of food that will not be produced tomorrow.

- Halting the exodus of our natural resources will be to no avail if we cling to methods of development advocated by those same monopolies, that mean the denial of the rational use of our resources.

- In defense of their interests, countries should aim at regional integration and joint action.

- Do not forget that the basic problem of most Third World countries is the absence of genuine social justice and popular participation in the conduct of public affairs. Without social justice the Third World will not be able to face the agonizingly difficult decades ahead.

Among the Third World countries that Perón took an interest in was Qaddafi’s Libya. When Perón returned to power a delegation was sent to Libya and various agreements on cooperation were signed. These included deals on scientific and economic cooperation between the two countries, cultural exchange, and the establishment of a Libyan-Argentine Bank for investment. Geopoliticallly Qaddafi’s belief in Arab unity aligned with Perón’s views on the creation of blocs to resist imperialism. Like Perón’s Justicialism, Qaddafi pursued an autarkic economic policy he termed “Arab socialism” aimed at the spiritual development of the nation. Qaddafi’s government outlasted Perón and he pursued aligned with Latin American resistors to American imperialism. His government was particularly close to Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela.

Hugo Chávez, the late leader of Venezuela explicitly declared, “I am really a Perónist. I identify with this man and his thought, who asked that our countries are no longer factories of imperialism.” Chávez revived Perón’s dream of a geopolitical bloc to challenge American domination with his Bolivarian Revolution, creating the Bolivarian Alliance for the People of our America (ALBA). As of this writing ALBA contains eleven member countries, Antigua and Barbuda, Bolivia, Cuba, Dominica, Ecuador, Grenada, Nicaragua, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and Venezuela. This bloc represents a collection of nations who reject American neo-liberalism and support social welfare and mutual economic aid. Given Chávez’s depiction as a thorn in the side of the American establishment, we can say that Perónist ideals represent a very real challenge to the American New World Order today.

While exile provided Perón with an opportunity to expand his geopolitical contacts and develop his philosophical vision, the election of Héctor Cámpora, a Perónist, who provided the opportunity for Perón to return and run for president, led to a third term as President of Argentina. However, in Perón’s absence, major rifts had developed in the Justicialist movement. The tension between left and right wing factions would eventually develop into open violence. The leftist factions eventually formed a radical guerrilla group, the Montoneros. Perónist guerrilla warfare had an early supporter in John William Cooke, a Perónist who eventually fled to Cuba. His influence eventually opened a way for Marxists to infiltrate the movement. Perón himself was strongly anti-communist, stating that “the victim of both communism and capitalism is the people.” Perón believed that communism and capitalism were part of an “international synarchy” against the people stating “The problem is to free the country and remain free. That is, we must confront the international synarchy of communism, capitalism, Freemasonry, and the Catholic Church, operated from the United Nations. All of these forces act on the world through thousands of agencies.” More right wing factions represented by the CGT claimed that “international synarchy” was attacking their leaders.

On the day of Perón’s return the conflict between left and right turned into open bloodshed at Ezeiza airport. Armed supporters from both tendencies had gathered and a shot rang out. The leftists returned fire, targeting those on the overpass podium. 500 Montoneros stormed the podium but were eventually routed by security forces. Overall 13 people were killed. Perón’s plane was diverted to ensure his safety.

Perón appointed staunch anti-communist José Rega as an intermediary to the left-wing Perónist Youth, signaling his opposition to their cause. Representatives of the Perónist Youth were removed from the Supreme Council of the Justicialist Party, and he instructed CGT leader José Rucci to purge the labor movement of Marxists. Two days after Perón’s election on September 23rd 1973, Rucci, his closest ally and likely political heir, was assassinated by Montoneros. The loss of his likely successor negatively impacted Perón’s already feeble health.

On the 19th of January 1974 the Marxist People’s Revolutionary Army (ERP) attacked the Azul army base. Perón believed they had been aided by Governor Oscar Bidegain, who had bused armed Leftists into Ezeiza. At a May Day rally Perón declared that the young left radicals were dishonoring the founders of the party, upon which the leftists walked out of the rally. Perón attempted to rally the people one last time, making a speech on a freezing day in June. His failing health declined steeply and he died on July 1st.

Following his death, his widow and vice-president Isabel took office. However, the Montoneros declared a full insurrection on the 6th of September. Moreover, economic conditions rapidly spun out of control, leading to a CGT general strike, combined with an escalating rebellion by the left. The Argentine Anticommunist Alliance, led by Rega, waged a bloody counter-revolutionary struggle. National production slowed to a crawl and inflation soared. In 1976, Isabel was overthrown by the army.

The ouster of Isabel Perón did not spell the end of Perónism, however. Currently Justicialist Party member Cristina Kirchner is the president of Argentina, succeeding her late husband, Nestor Kirchner. While she has received some criticism from more traditional Perónists, she has attempted to repudiate the polices of neo-liberalism. In 2012 a bill was introduced to ensure that the Central Bank acted in the interest of social equity. Moreover, Perónist movements outside the Kirchner regime enjoy a great deal of support. Outside of Argentina, the late Hugo Chávez lead the Perón-influenced Bolivarian Revolution, as previously mentioned. It appears, that after years of struggle and heartbreak, Perónism is once again leading Latin America’s resistance to US neo-liberal imperialism.

Kerry Bolton’s book should become essential reading for all of those who wish to see how a mass movement can be built from the ground up to challenge superpowers. It places Perón in his rightful place as one of the great Third Position thinkers, rallying the workers against communism and capitalism for the spiritual growth of the nation. It will not be lengthy digressions on IQ and philosophy that challenge the American liberal empire, but showing the common man the way to a higher life, against the forces of greed and materialism. Perónism represents a true creed of social justice, one of service to society. If there is to be any real progress for the New Right, they must embrace the shirtless ones who toil for their nation as Perón did.

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2014/12/kerry-boltons-peron-and-peronism/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/PeronandPeronism.jpg

[2] Perón and Perónism: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0992736544/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=0992736544&linkCode=as2&tag=countecurrenp-20&linkId=QW4F5XW2P5ZWSDC6

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : argentine, eva peron, juan peron, amérique du sud, amérique latine, justicialisme, histoire, livre |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 02 mars 2014

Une biographie de Juan Peron par Jean-Claude Rolinat

Une biographie de Juan Peron par Jean-Claude Rolinat

Article publié dans Rivarol

n°3130 du 20 février 2014

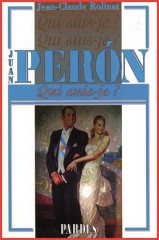

Après la très intéressante biographie consacrée à Evita Peron par Jean-Claude Rolinat, le voici qui récidive avec le portrait de Juan Peron et du Justicialisme.

Paraphrasant une publicité d'une célèbre marque gazeuse, il note que le péronisme avait « le goût du fascisme, l'odeur du fascisme et la couleur du fascisme, mais ce n'était pas du fascisme ».

Une dictature ? Pas davantage. Tout au plus un pouvoir autoritaire, une république forte et indépendante. L'expression parlementaire était maintenue et les élections étaient libres. Il n'y avait pas, comme en Italie mussolinienne, ou au Portugal salazariste, ou en Espagne franquiste, de parti unique. Le parti justicialiste était certes dominant et le syndicat, la Confédération générale du travail (CGT) largement majoritaire. Mais l'Argentine ne sera jamais un État corporatiste tels l'Italie ou le Portugal, ni national-syndicaliste, tel le Portugal. Peron était un vrai nationaliste qui refusa l'alignement de l'Argentine sur les États-Unis, tout en refusant de tomber sous la coupe de Moscou. Il fera de l'Argentine la cinquième puissance économique au monde !

Né le 8 octobre 1895, issu de l'immigration basque et italienne, il embrassa tout naturellement la carrière militaire et deviendra ultérieurement attaché militaire en Italie mussolinienne. Il y découvre les idées du Fascio et, hissé à la charge de secrétaire d’État au Travail deviendra le protecteur des humbles tout en cherchant à éviter dira-t-il, « les erreurs de Mussolini ». Il va concocter toute une série de mesures sociales qui le rendront ultra-populaire : régime de retraite étendu à deux millions de salariés, prévention des accidents du travail, légalisation des syndicats, obligation de signature de conventions collectives pour les employeurs et les salariés, création de tribunaux d'arbitrage, législation sur les congés payés. Ces mesures vont susciter l'hostilité des classes aisées pour qui le régime est trop réformiste, voire révolutionnaire. Washington ira jusqu'à rappeler son ambassadeur.

La vraie date de naissance du péronisme est le 17 octobre 1945, « el dia de la leatad », toujours fêté. Le président Farrell, poussé par la rue, offre le pouvoir à Péron. Ce jour-là, les masses populaires descendent des banlieues. Les ouvriers, manches de chemises retroussées, tombent la veste. C'est ce jour-là que naît l'expression descamisados (sans chemise) qui restera le surnom des militants péronistes.

Peron épousera Evita le 22 octobre 1945. Jean-Claude Rolinat a décrit dans son précédent ouvrage le rôle considérable que joua Evita aux côtés du général. Les élections du 8 avril 1946 sont un triomphe pour le péronisme. Avec 55% des suffrages Péron remporte non seulement l'élection présidentielle mais obtient la majorité à la Chambre et au Sénat, et tous les postes de gouverneurs de province, sauf un. L'armée se montrera cependant assez vite agacée par l'activité débordante d'Evita, sa popularité grandissante et le faste dont elle s'entoure. Accusée de népotisme, elle répliquait : « Entraide familiale d'abord ! » Eva aime les toilettes et les parures luxueuses et symbolise ce qu'aujourd'hui on nomme le « bling-bling ». Mais l'étalement de cette richesse ne scandalise nullement le peuple. Elle ne suscite que la jalousie des « bien-pensants ». La sournoise maladie qui rongeait Evita la contraignit de s'aliter en janvier 1950. Elle a trente ans, elle se savait condamnée. Le pape Pie XII prie pour son rétablissement. Le célèbre pilote de courses Fangio se précipite à son chevet. Dans toutes les églises du pays des femmes implorent la « Reine du Ciel » pour qu'elle intercède pour le salut de la « Reine des descamisados ». Son état s'améliora quelque peu, mais la maladie poursuivait son œuvre.

A l'approche de l'hiver 1951, une nouvelle élection présidentielle s'annonce. Les péronistes pressent le couple de former un 'ticket'. Lui à la présidence, elle à la vice-présidence, ce qui lui assurerait de succéder à son mari si celui-ci venait à disparaître. Mais l'opposition se déchaîne et l'armée devient menaçante. Celle qui disait : « quand les c...s de Péron descendent jusqu'aux pieds, je suis là pour les lui remonter », assiste, désespérée, à la reculade du président. Santa Evita s’éteindra le 26 juillet 1952, à 19h40, suscitant une intense émotion populaire. Dès lors, Peron ne sera plus tout à fait Peron. Un coup d'Etat militaire chassera le général du pouvoir le 15 septembre 1955.

En exil durant 18 ans, il reviendra en Argentine en 1973 pour se faire élire avec 61% des suffrages, à la présidence, avec à ses côtés sa nouvelle épouse, Isabella, qui sera élue à la vice-présidence et lui succédera à son décès 9 mois plus tard. Isabella n'arrive pas à la cheville d'Evita. Elle s'entoure de personnages parfois douteux, dont José Lopez Rega, surnommé « le sorcier », un redoutable intrigant. L'armée mettra fin à ces fantaisies en kidnappant littéralement en vol la présidente qui fut expédiée sous bonne garde dans les Andes, à 1 800 km de la capitale, où elle passa cinq années de prison dans les geôles du général Videla. Le péronisme sans Péron et sans Evita n'avait plus guère d'existence...

Juan Péron, de Jean-Claude Rolinat, collection Qui suis-je ? Editions Pardès, 2014, 126 pages, 12,00 €

00:05 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, juan peron, evita peron, argentine, amérique latine, amérique du sud, péronisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook