Among the vast array of sources that influenced Tolkien in the creation of his legendarium was the Kalevala, a collection of Finnish folk poetry compiled and edited by the Finnish physician and philologist Elias Lönnrot. Much scholarship exists on Tolkien’s Norse, Germanic, and Anglo-Saxon influences, but his interest in the Kalevala is not as often discussed.

The Kalevala was first published in 1835, but the tales therein date back to antiquity and were handed down orally. The poems were originally songs, all sung in trochaic tetrameter (now known as the “Kalevala meter”). This oral tradition began to decline after the Reformation and the suppression of paganism by the Lutheran Church. It is largely due to the efforts of collectors like Lönnrot that Finnish folklore has survived.

The Kalevala was first published in 1835, but the tales therein date back to antiquity and were handed down orally. The poems were originally songs, all sung in trochaic tetrameter (now known as the “Kalevala meter”). This oral tradition began to decline after the Reformation and the suppression of paganism by the Lutheran Church. It is largely due to the efforts of collectors like Lönnrot that Finnish folklore has survived.

Lönnrot’s task in creating the Kalevala was to arrange the raw material of the poems he collected into a single literary work with a coherent arc. He made minor modifications to about half of the oral poetry used in the Kalevala and also penned some verses himself. Lönnrot gathered more material in subsequent years, and a second edition of the Kalevala was published in 1849. The second edition consists of nearly 23,000 verses, which are divided into 50 poems (or runos), further divided into ten song cycles. This is the version most commonly read today.

The main character in the Kalevala is Väinämöinen, an ancient hero and sage, or tietäjä, a man whose vast knowledge of lore and song endows him with supernatural abilities. Other characters include the smithing god Ilmarinen, who forges the Sampo; the reckless warrior Lemminkäinen; the wicked queen Louhi, ruler of the northern realm of Pohjola; and the vengeful orphan Kullervo.

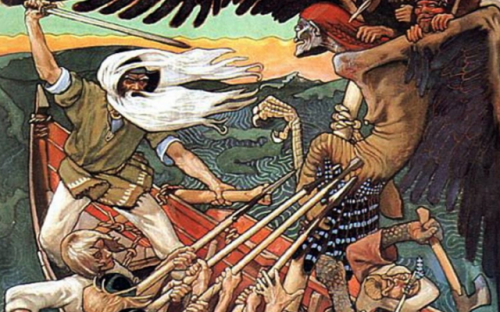

Much of the plot concerns the Sampo, a mysterious magical object that can produce grain, salt, and gold out of thin air. The exact nature of the Sampo is ambiguous, though it is akin to the concept of the world pillar or axis mundi. Ilmarinen forges the Sampo for Louhi in return for the hand of her daughter. Louhi locks the Sampo in a mountain, but the three heroes (Väinämöinen, Ilmarinen, and Lemminkäinen) sail to Pohjola and steal it back. During their journey homeward, Louhi summons the sea monster Iku-Turso to destroy them and commands Ukko, the god of the sky and thunder, to incite a storm. Väinämöinen wards off Iku-Turso but loses his kantele (a traditional Finnish stringed instrument that Väinämöinen is said to have created). A climax is reached when Louhi morphs into an eagle and attacks the heroes. She seizes the Sampo, but Väinämöinen attacks her, and it falls into the sea and is destroyed. Väinämöinen collects the fragments of the Sampo afterward and creates a new kantele. In nineteenth-century Finland, Väinämöinen’s fight against Louhi was seen as the embodiment of Finland’s struggle for nationhood.

It is likely that Finland would not exist as an independent nation were it not for the Kalevala. The poem was central to the Finnish national awakening, which began in the 1840s and eventually resulted in Finland’s declaration of independence from Russia in December 1917. It also played a role in the movement to elevate the Finnish language to official status.

The publication of the Kalevala brought about a flowering of artistic and literary achievement in Finland. The art of Finland’s greatest painter, Akseli Gallen-Kallela, is heavily influenced by Finnish mythology and folk art, and many of his works (The Defence of the Sampo, The Forging of the Sampo, Lemminkäinen’s Mother, Kullervo Rides to War, Kullervo’s Curse, Joukahainen’s Revenge) depict scenes from the Kalevala. The Kalevala has also influenced a number of composers, most notably Sibelius, whose Kalevala-inspired compositions include his Kullervo, Tapiola, Lemminkäinen Suite, Luonnotar, and Pohjola’s Daughter.

Tolkien first read the Kalevala at the age of 19. The poem had a great impact on him and remained one of his lifelong influences. While still at Oxford, he wrote a prose retelling of the Kullervo cycle. This was his first short story and “the germ of [his] attempt to write legends of [his] own.”[1] His fascination with the Kalevala during this time also inspired him to learn Finnish, which he likened to an “amazing wine” that intoxicated him.[2] Finnish was an important influence on the Elvish language Quenya.

In the Kalevala, Kullervo is an orphan whose tribe was massacred by his uncle Untamo. After attempting in vain to kill the young Kullervo, Untamo sells him as a slave to Ilmarinen and his wife. Kullervo later escapes and learns that some of his family are still alive, though his sister is still considered missing. He then seduces a girl who turns out to be his sister; she kills herself upon this realization. Kullervo vows to gain revenge on Untamo and massacres Untamo’s tribe, killing each member. He returns home to find the rest of his family dead and finally kills himself in the spot where he seduced his sister. The character of Kullervo was the main inspiration for Túrin Turambar in The Silmarillion.

There are a handful of other parallels. The hero Väinämöinen likely provided inspiration for the characters of Gandalf and Tom Bombadil, particularly the latter.[3] Tom Bombadil is as old as creation itself, and his gift of song gives him magical powers. The magical properties of singing also feature in The Silmarillion when Finrod and Sauron duel through song and when Lúthien sings Morgoth to sleep (as when Väinämöinen sings the people of Pohjola to sleep). Ilmarinen likely inspired the character of Fëanor, creator of the Silmarils.[4] The Silmarils are much like the Sampo in nature, and the quest to retrieve them parallels the heroes’ quest to capture the Sampo.

The animism that pervades Tolkien’s mythology (as when Caradhras “the Cruel” attempts to sabotage the Fellowship’s journey or when the stones of Eregion speak of the Elves who once lived there) also hearkens back to the Kalevala, in which trees, hills, swords, and even beer possess consciousness.

For Tolkien, the appeal of the Kalevala lay in its “weird tales” and “sorceries,” which to him evinced a “very primitive undergrowth that the literature of Europe has on the whole been steadily cutting away and reducing for many centuries . . . .” He continues: “I would that we had more of it left — something of the same sort that belonged to the English . . . .”[5]

The desire to create a national mythology for England in the vein of Lönnrot’s Kalevala was the impetus behind Tolkien’s own legendarium. Not unlike Lönnrot, he envisioned himself as a collector of ancient stories whose role it was to craft an epic that would capture the spirit of the nation. He writes in a letter:

. . . I was from early days grieved by the poverty of my own beloved country: it had no stories of its own (bound up with its tongue and soil), not of the quality that I sought, and found (as an ingredient) in legends of other lands. There was Greek, and Celtic, and Romance, Germanic, Scandinavian, and Finnish (which greatly affected me); but nothing in English . . . . I had a mind to make a body of more or less connected legend, ranging from the large and the cosmogonic, to the level of romantic fairy-story — the larger founded on the lesser in contact with the earth, the lesser drawing splendour from the vast backcloths — which I could dedicate simply to England; to my country . . . . The cycles should be linked to a majestic whole, and yet leave scope for other minds and hands, wielding paint and music and drama.[6]

Tolkien had England in mind, but his mythology is one that all whites can unite around, in the same manner that the races of the Fellowship united to save Middle-earth. The heroic and racialist themes in Tolkien’s mythology are readily apparent, and the fight against the forces of evil parallels the current struggle.

The role of the Kalevala in Finland’s fight for independence attests to the revolutionary potential of literature and art. Tolkien’s mythology offers rich material from which to draw and indeed has already inspired many works of art, music, literature, etc., as Tolkien himself hoped.[7] Perhaps the revolution will be led by Tolkien fans.

Notes

1. J. R. R. Tolkien, The Story of Kullervo, ed. Verlyn Flieger (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017), 52.

2. Ibid., 136.

3. Gandalf’s departure to Valinor also brings to mind when Väinämöinen sails away to a realm located in “the upper reaches of the world, the lower reaches of the heavens” at the end of the Kalevala.

4. Ilmarin, the domed palace of Manwë and Varda, is another possible allusion to Ilmarinen, who created the dome of the sky. The region of the stars and celestial bodies in Tolkien’s cosmology is called Ilmen (“ilma” means “air” in Finnish). Eru Ilúvatar also recalls Ilmatar (an ancient “air spirit” and the mother of Väinämöinen).

5. The Story of Kullervo, 105. This comes from his revised essay, which was written sometime in the late 1910s or early 20s.

6. J. R. R. Tolkien, The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, ed. Humphrey Carpenter (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1981), 144.

7. Here could be the place to note that a major exhibit of Tolkien’s papers, illustrations, and maps recently opened in Oxford and will soon be accompanied by a book (Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth).

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg