One hundred and forty-nine years ago, on June 19, 1867, Maximilian von Hapsburg—Emperor of Mexico, brother to Austrian Emperor Franz Josef, and descendant of Holy Roman Emperors—was shot by a firing squad of rebels in Querétaro, Mexico. Maximilian stood six-foot-two, had blond hair and blue eyes, and was 34 years of age. He had been Emperor of Mexico for barely two-and-a-half years.

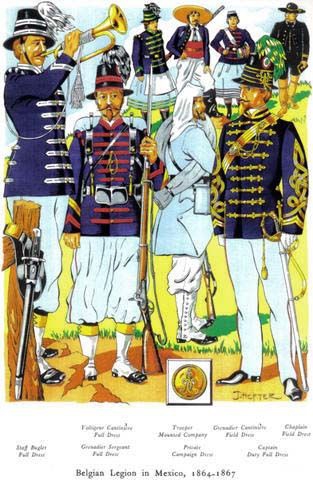

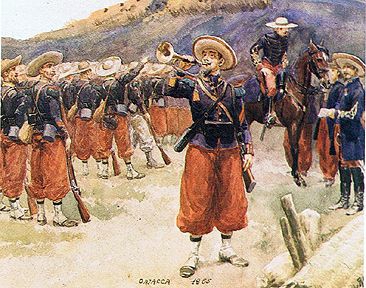

So ended the short life of Maximilian, and the much briefer life of Imperial Hapsburg Mexico. Often viewed as a sort of black comedy out of Evelyn Waugh—aristocratic simpleton moves to the tropics and gets lynched by noble savages—the Maximilian story is a grave one that reverberates to the present day. Put simply, Maximilian’s rule was a valiant attempt to turn a perpetually bankrupt, disorderly Mexico into something else—an orderly, prosperous, Europeanized country. A transformed Mexico, newly planted with arrivals from Austria, Hungary, Germany, France and, perhaps most importantly, the Confederate States of America.

So ended the short life of Maximilian, and the much briefer life of Imperial Hapsburg Mexico. Often viewed as a sort of black comedy out of Evelyn Waugh—aristocratic simpleton moves to the tropics and gets lynched by noble savages—the Maximilian story is a grave one that reverberates to the present day. Put simply, Maximilian’s rule was a valiant attempt to turn a perpetually bankrupt, disorderly Mexico into something else—an orderly, prosperous, Europeanized country. A transformed Mexico, newly planted with arrivals from Austria, Hungary, Germany, France and, perhaps most importantly, the Confederate States of America.

In 1865-66, Germans founded colonies in Yucatan. Confederates went to Monterey and Cordoba and the new town of Carlota, 70 miles west of Veracruz, where they farmed, built sawmills and freight companies, and helped construct the first-ever long-distance railway line between the Gulf Coast and Mexico City.[1][2][3] During Maximilian’s brief reign, Mexico’s international debts were settled, while trade and commerce revived.[4]

Not for long of course. Imperial Mexico got strangled at birth by its northern neighbor. The U.S.A. wanted a weak, unstable country at its southern border, so it armed and funded the guerrillas who overthrew and executed the Emperor.

Now, this is not the conventional, vague explanation one usually hears for Maximilian’s reign and collapse. The usual story blames it all on the French. We’re told Maximilian was no more than a puppet emperor installed by Napoleon III, and propped up by the French army and Foreign Legion (who were there originally for reasons to do with Mexico defaulting on debts, or something). Thus when those French forces withdrew, the Imperial regime collapsed.

There are a couple of serious problems with this potted history. For one thing, contemporary reports tell us Maximilian’s rule was fairly popular for most of his reign. The largely European upper classes—grandees, business people, clergy—liked him from the start (and cooled on him only when he proved to be a little too progressive and liberal for their taste).The indios and common people particularly welcomed him, seeing in this monarch an end to the constant upheavals that had colored the national scene ever since Mexico’s dubious independence in 1821.[5]

There had been at least 40 different governments in four decades; the exact number is indeterminable. Maximilian’s opponents — Benito Juarez, Porfirio Diaz, and their followers — were a ragtag collection of so-called “Liberal” bureaucrats and warlords, essentially the same sort of self-seeking politicos who had been exploiting the country since the 1820s. By the time Maximilian arrived in Mexico at the end of 1864, Juarez and Diaz, et al. had been chased to the banks of the Rio Grande, where they waited for succor from the United States.

It was not long in coming. The Washington regime had determined to sabotage the Imperial government however it could. This was far and away the determining factor in Maximilian’s downfall. As the American Civil War wound down in 1865, the Federals turned their sights on the Southwest, and gave the rebel warlords all the gold [6] and guns they needed to keep up their guerrilla campaign. According to reports, 30,000 rifles were deposited on the riverbank near El Paso by Gen. Philip Sheridan.[7] With the South now defeated, the U.S. Army had plenty of surplus. Sheridan also brought an “army of observation” of 50,000 men to the border, to support the rebels and threaten the Imperial and French troops.[8] Whenever possible, the Federals prevented Southerners from embarking to the new colonies by ship.[9] Washington refused diplomatic recognition to Maximilian’s government, and went so far as to brazenly warn Austria and other European countries not to aid Maximilian. (The United States, warned Secretary of State Seward, “cannot consent” to European intervention and establishment of “military despotism” in the Western Hemisphere.[10])

Bizarrely, Washington continued to recognize insurgent leader Benito Juarez as Mexican president long after his term ended in 1864.[11]

The U.S.’s persistent and calculated support for the rebels shows that Maximilian’s fall was neither inevitable nor foreordained. Which makes it very compelling to imagine what might have become of Mexico had Maximilian’s cause prevailed. Would Imperial Hapsburg Mexico have become a sort of Austria-Hungary of the tropics, full of ski resorts, opera festivals and retirement chalet-condos in the Sierra Madre? Perhaps the current Hapsburg heir would be Emperor of Mexico.

The U.S.’s persistent and calculated support for the rebels shows that Maximilian’s fall was neither inevitable nor foreordained. Which makes it very compelling to imagine what might have become of Mexico had Maximilian’s cause prevailed. Would Imperial Hapsburg Mexico have become a sort of Austria-Hungary of the tropics, full of ski resorts, opera festivals and retirement chalet-condos in the Sierra Madre? Perhaps the current Hapsburg heir would be Emperor of Mexico.

Or — to consider the Confederate heritage — might Mexico have become the fulcrum of an expansionist military/commercial empire, eventually encompassing all of Central America, much of the Caribbean, and perhaps even South America — a Knights of the Golden Circle dream, fulfilling its manifest destiny?

Either way, in order to survive it would need to crack its mestizo problem, which after all was the main cause of Mexico’s instability. Maximilian himself never seems to have explored racial matters or noted the connection between Mexico’s heterogeneous, mostly nonwhite population, and its tumbledown governmental administration; but no doubt his ex-Confederate advisors were no doubt ready to enlighten him. In any case, the clear policy of Imperial Mexico was to fill the country up with white people.

Extrapolating to the present day, one might speculate that the big racial discussion a century-and-a-half later would concern illegal immigration . . . particularly nonwhite aliens and immigrant from the north of the border. (“Decades ago we allowed some blacks to come down to work in the Konditoreien and Krankenhausen . . . We felt so sorry for them, the way they were treated in the U.S. of A. Those little negro girls in Little Rock! We didn’t know what they were really like. But now! Right outside Charlottenburg, the toniest suburb of Mexico-Stadt, there’s this ghastly slum that looks like the South Side of Chicago . . .”)

But to return to less whimsical musings . . .

Why Maximilian? Why was he there? For most people this is a complete conundrum. As noted above, the origins of Imperial Hapsburg Mexico are generally skimmed over in (American) history, dismissed as an incursion by “the French” for some vague purposes of empire-building or debt-collection. The whole adventure is known mainly through celebration of Cinco de Mayo, which commemorates a minor battle from 1862, years before Maximilian was anywhere on the scene.

In grade-school and high-school history, the Maximilian episode is often (or used to be) presented as an object lesson in the “Monroe Doctrine,” the 1823 promulgation that the United States must regard as “unfriendly” any “interference” by European powers in the political affairs of independent states in the New World. But even if you take the Monroe Doctrine seriously (and it’s pretty hard to, considering that it’s nothing more than a unilateral declaration of a nation’s supposed “sphere of influence”), the Doctrine does not strictly apply to the Maximilian case. Maximilian did not rule Mexico as an Austrian prince or satrap of France. He was ostensibly offered the Imperial crown by the “people of Mexico,” and however dubious that vox populi might be, Maximilian accepted the offer in good faith, and took it as a duty. As Emperor of Mexico he did not owe fealty to any other state or prince.

The many evasive characterizations of the Maximilian story—European interference, imperial aggrandizement, debt-collection, et al.—all avoid the fundamental reason why Maximilian was brought in. And that was the horrifying disorder and lawlessness that had characterized Mexico in the generation or so since independence. One can argue that disorder is just innate to Mexico. Regardless, the chaos had become particularly noticeable by the early 1860s, when after years of governmental corruption, the Benito Juarez administration announced it would default on the loans made by overseas investors. (The crisis that precipitated the 1862 military intervention by France, along with Britain and Spain.) A good example of this corruption, or incompetence, is shown by the Veracruz-to-Mexico City railway mentioned above. This had originally been planned, and concession granted, in 1837. But construction of the 300-mile route never really commenced till 1865, under Maximilian. At this time Mexico did not have a single long-distance railway.

The many evasive characterizations of the Maximilian story—European interference, imperial aggrandizement, debt-collection, et al.—all avoid the fundamental reason why Maximilian was brought in. And that was the horrifying disorder and lawlessness that had characterized Mexico in the generation or so since independence. One can argue that disorder is just innate to Mexico. Regardless, the chaos had become particularly noticeable by the early 1860s, when after years of governmental corruption, the Benito Juarez administration announced it would default on the loans made by overseas investors. (The crisis that precipitated the 1862 military intervention by France, along with Britain and Spain.) A good example of this corruption, or incompetence, is shown by the Veracruz-to-Mexico City railway mentioned above. This had originally been planned, and concession granted, in 1837. But construction of the 300-mile route never really commenced till 1865, under Maximilian. At this time Mexico did not have a single long-distance railway.

The post-independence years had brought a complete breakdown of communication and law-enforcement through most of Mexico. Traveling any distance overland was a dangerous expedition, one that should only be taken only with armed guard. A fact of life celebrated in a popular painting genre of the period: the robbery of a stagecoach, or diligencia. Usually titled something like “Assault on the Diligencia,” these paintings display masked bandits having their way with stagecoach booty and despairing passengers.

The diligencia genre can be considered an ancestor of the film western, particular such examples as John Ford’s 1939 Stagecoach. (The Mexican title of which is, oddly enough, La Diligencia.) Thus the disorder of the Mexican outback was in fact the original Wild West. Its lawlessness is of great significance to Americans, because the background of the western, in fiction and film — unpatrolled wilderness, distant towns, bandits around every mountain pass — is basically a legacy of the former Mexican rule. Or non-rule, rather. In this context Maximilian was the befuddled new sheriff, or dude from the East. He comes to town to bring civilization and order, and gets his hat shot off.

Notes

1. Neal and Kremm, The Lion of the South: General Thomas C. Hindman, Mercer University Press, 1997.

2. David M. Pletcher, “The Building of the Mexican Railway,” Hispanic American Historical Review, Duke University Press, Feb. 1950.

3. Carl Coke Rister,”Carlota, A Confederate Colony in Mexico,” The Journal of Southern History, Feb. 1945.

4. J. Kemper, Maximilian in Mexico, tr. by Upton, 1911.

5. J. Kemper, op. cit.

6. Besides supplying a munitions depot on the Rio Grande, the U.S. financed the insurgents by buying heavily discounted war bonds. Brian Loveman, No Higher Law: American Foreign Policy and the Western Hemisphere Since 1776. UNC Press, 2010.

7. NY Times, 2013. http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/10/04/maximilia... [3]

8. Loveman, op. cit.

9. (General Sheridan, again.) Rister, op. cit.

10. Loveman, op.cit.

11. J. Kemper, op. cit.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg