samedi, 23 novembre 2013

Occult Roots of the Russian Revolution

Occult Roots of the Russian Revolution

Ex: http://www.gnostics.com

Dearest friend, do you not see

All that we perceive –

Only reflects and shadows forth

What our eyes cannot see.

Dearest friend, do you not hear

In the clamour of everyday life –

Only the unstrung echoing fall of

Jubilant harmonies.

– Vladimir Soloviev, 1892

The Great Russian Revolution of 1917, launched by Vladimir Lenin and his Bolshevic party, profoundly influenced the history of the twentieth century. The fall of the Russian Empire and its replacement by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics ushered in а new аgе in world politics. More than this, the Russian Revolution was the triumph of а dynamic revolutionary ideology that directly challenged Western capitalism. But what of the hidden origins of this Revolution? Did secret influences contribute to the victory of Lenin and the Bolshevics?

Innumerable books, not to forget massive scholarly studies, are devoted to examining the Russian Revolution and the rise of Soviet Communism. All this impressive research is almost exclusively devoted to the obvious political, economic and social dimensions, i.e. the surface manifestations of history. However, within or behind this mundane history lies another reality that is more interesting and more important than the everyday analysis offered by mainstream historians and writers.

Establishment historians pay little attention to the remarkable impact occult and Gnostic ideas had on the rise of Bolshevism and the victory of the Russian Revolution.

A number of social and political movements, including Marxism and Lenin’s Bolshevism, have been linked to Gnosticism, which flourished in the early centuries of the Christian era. The political scientists A. Besancon and L. Pellicani argue the intellectual roots of Russian Bolshevism are a structural repetition of the ancient Gnostic paradigm. A distinguishing feature of Gnosticism is an illusive, symbolic interpretation of reality, including history.

For the early Christian Gnostics the Absolute – termed the ‘Unknown Father’– has nothing in common with the wrathful ‘God’ worshipped by theist religion. In fact, for these Gnostics, the ‘God’ of the Old Testament is the adversary of their ‘Unknown Father’, the true God. Our world, including all human institutions, is not the work of the true God, but of a false creator, the Demiurge, who keeps us captive in the world, away from the divine light and truth.

Therefore, in Gnosticism, the world is merely a sort of illusion, a set of allegorical symbols, a reverse image of the real essence of history. Man, who is asleep to his inner potential, must awake and become an active partner of the ‘Unknown Father’ in the transformation of all life. Otherwise he remains a prisoner in what the eminent Russian Gnostic philosopher Vladimir Solviev (1853-1900) aptly described as “a kind of nightmare of sleeping humanity.” A number of Gnostic communities – like nineteenth century communists – held contempt for material goods and lived communally, teaching “the world and its laws, religious, moral and social, are of little relevance to the plan of salvation.”1

Gnostics, Mystic Sects & Radicals

Russian mystical sects played an extremely important part in the Bolshevik revolution, on the side of the Bolsheviks. In spite of their rejection of the state and the church, these sects were deeply nationalistic, since their members were hostile to foreign innovations. They hated the West.

— Mikhail Agursky, The Third Rome

Throughout nineteenth century Europe we find numerous connections between Gnostics, mystics, occultists and radical socialists. They constituted what the historian James Webb calls “a progressive underground” united by a common opposition to the established order of their day. Constantly, Webb writes, “we find socialists and occultists running in harness.”2 Sundry spiritual communities emerged across the United States, with clear Gnostic and occult doctrines, which attempted to follow a pure communistic life style. Victoria Woodhull, the president of the American Association of Spiritualists during the 1870s, was a radical socialist. Woodhull believed that Spiritualism signified not only religious enlightenment, but also a cultural, political and social revolution. She published the first English translation of the Communist Manifesto and tried in vain to persuade Karl Marx that the goals of Spiritualism and Communism were the same.

Dissident Christian mystics, spiritualists, occultists and radical socialists often found themselves together at the forefront of political movements for social justice, worker’s rights, free love and the emancipation of women. Nineteenth century occultists and socialists even used the same language in calling for a new age of universal brotherhood, justice and peace. They all shared a charismatic vision of what the future could be – a radical alternative to the oppressive old political, social, economic and religious power structures. And more often than not they found themselves facing the same common enemy in the unholy alliance of State and Church.

The birth of radical socialist ideas in Russia cannot be easily separated from the spiritual communism practiced by diverse Russian sects. For centuries folk myths nourished a widespread belief in the possibility of an earthly communist paradise united by fraternal love, where justice, truth and equality prevailed. One prominent Russian legend told of the lost land of Belovode (the Kingdom of the White Waters), said to be “across the water” and inhabited by Russian Old Believer mystics. In Belovode, spiritual life reigned supreme, and all went barefoot sharing the fruits of the land and their labour. There were no oppressive rules, crime, and war. Another Russian legend concerned Kitezh, the radiant city beneath the lake. Kitezh will only rise from the waters and appear again when Russia returns to the true Christ and is once more worthy to see it and its priceless treasures. Early in the twentieth century such myths captured the popular imagination and were associated with the hopes of revolution.

In the latter half of the seventeenth century, a schism occurred within the Russian Orthodox Church of a new religious movement called the Old Believers. The result was that many Russian spiritual dissidents took courage from the split to found their own communities, giving vent to Gnostic ideas that had long been simmering underground. The Old Believers, in the face of severe repression, clung tenaciously to their ancient mystic tradition and expressed their separation from the official world of Imperial Orthodox Russia in collective migration to the fringes of the state, mass suicide by fire, rebellion, and a monastic communism.

Gnostic communities, with their communalism and disdain for private property, proliferated throughout Russia in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Known by a variety of names such as Common Hope, United Brotherhood, Love of Brotherhood, Righthanded Brotherhood, White Doves, Believers in Christ, Friends of God, Wanderers, their followers reportedly numbered in the hundreds of thousands. Ruthlessly persecuted by the authorities, they made up a spiritual underground, often hiding themselves from inquisitive eyes. A countrywide revolutionary sectarianism that rejected the state, the church, society, law, and even religious commandments, which they declared were abolished when the Holy Spirit descended to humanity.

The origin of Gnostic ideas in Russia is difficult to trace, but they appear to be an outgrowth of two powerful spiritual impulses in Russian religious history. The first is the Christian esoteric tradition preserved within the monastic communities of the Russian Orthodox Church. A mystical tradition going back by way of Greek Neoplatonism, Origin and Clement of Alexandria to St. John the “beloved disciple”. “Russian Orthodox mystical theology has bent more than a little in the direction of the Gnostic heresy,” notes the historian Maria Carlson.3 The second impulse originated with Essene and Manichean missionaries who reached Russia in the early centuries of the Christian era. An impulse later given new vitality by the Bogomils whose Gnostic teachings had gained a foothold in Russia by the thirteenth century.

By the end of the nineteenth century occult and Gnostic ideas enjoyed wide circulation among all segments of the Russian population. At one point the Russian philosopher Nicholas Berdyaev (1874-1948) welcomed the Gnostics, urging “Gnosticism should be revived and should enter into our life for all time.”4 After the 1917 Revolution, Gnosticism, observed the Russian scholar Mikhail Agursky, “contributed considerably to Soviet culture and even influenced Soviet political life. Its foundations were laid before the revolution…[by] several gnostic trends in nineteenth century Russian culture.”

While Russian Gnostics rejected the world order and strove to live by the apostolic precept to hold “all things in common,”5 they were also profoundly aware of the approaching end of the age. “Russian popular Gnosticism had a very pronounced apocalyptic character,” says Mikhail Agursky. “Russian mystical sectarians lived in anticipation of a catastrophe. The degradation of human life demanded purifying fire from heaven, which would devour the new Sodom and Gomorrah and replace them with the Kingdom of God. Any revolution could easily be identified by such sectarians as this fire, regardless of its external form.”6

Russian Socialism

Bolshevik collectivism had roots in long-standing Russian values of individual self-sacrifice. The suffering, martyrdom, humility, and sacrifice of Christ was deeply embedded in the texture of Russian religious thought and practice, and the lives of Russian saints were a litany of suffering. The Old Believers, heretics in the eyes of the official church for their adherence to their own version of the truth, suffered persecution for centuries at the hands of the government and sought escape in mass immolation, colonization, and, finally, economic mutual aid.

— Robert C. Williams, The Other Bolsheviks

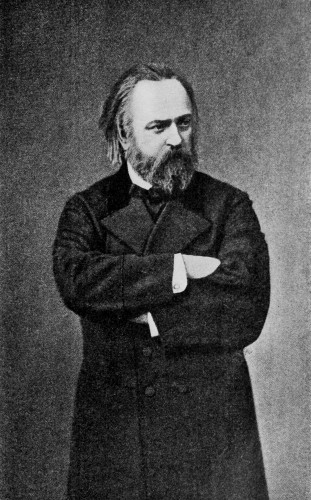

Alexander Herzen (1812-1870), seen by many as the father of Russian socialism, was a friend and admirer of the French revolutionary Proudhon, who viewed himself as a Christian socialist. Proudhon worked intermittently all his adult life on a never completed study of the original teachings of Jesus Christ. Herzen also paid special attention to Russia’s persecuted religious sectarians. He printed a special supplement for the Old Believers, the mystic Christian traditionalists who had been driven out of the Russian Orthodox Church. Nicholas Chernyshevsky, another Russian socialist thinker of the nineteenth century, wrote an article in praise of the “fools for Christ’s sake” and defended members of the spiritual underground.

Alexander Herzen (1812-1870), seen by many as the father of Russian socialism, was a friend and admirer of the French revolutionary Proudhon, who viewed himself as a Christian socialist. Proudhon worked intermittently all his adult life on a never completed study of the original teachings of Jesus Christ. Herzen also paid special attention to Russia’s persecuted religious sectarians. He printed a special supplement for the Old Believers, the mystic Christian traditionalists who had been driven out of the Russian Orthodox Church. Nicholas Chernyshevsky, another Russian socialist thinker of the nineteenth century, wrote an article in praise of the “fools for Christ’s sake” and defended members of the spiritual underground.

The Russian radicals of the 1800s, in the words of James H. Billington, looked upon “socialism as an outgrowth of suppressed traditions within heretical Christianity.”7 They saw the genesis of Russian socialism in the spiritual underground of the Gnostics and religious sectarians. One influential network of Russian socialists openly claimed to be rediscovering “the teaching of Christ in its original purity,” which “had as its basic doctrine charity and its aim the realisation of freedom and the destruction of private property.”8

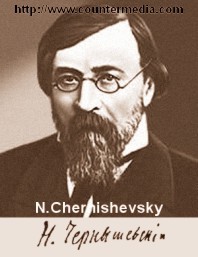

Nicholas Chernyshevsky (1828-1889), who spent much of his life in penal servitude, penned the utopian novel What Is To Be Done? as a vision of the future new society and a guidebook for the revolutionaries who would build it. Chernyshevsky wrote:

Nicholas Chernyshevsky (1828-1889), who spent much of his life in penal servitude, penned the utopian novel What Is To Be Done? as a vision of the future new society and a guidebook for the revolutionaries who would build it. Chernyshevsky wrote:

Then say to all: this is what will come to pass in the future, a radiant and beautiful future. Have love for it, strive toward it, work on behalf of it, bring it ever nearer, bear what you can from it into your present life. The more you can carry from that future into your present life, the more your life will be radiant and good, the richer it will be in happiness and pleasure.

Chernyshevsky’s novel inspired two generations of idealistic young radicals. Among them was Alexandre Ulianov, the beloved elder brother of V.I. Lenin. He was executed in 1887 for his part in the attempted assassination of Tsar Alexander III. Vladimir Lenin told how Chernyshevsky’s What Is To Be Done? “captivated my brother, and captivated me… It transformed me completely.” What impressed the future leader of the Russian Revolution was how Chernyshevsky:

not only demonstrated the necessity for every correctly thinking and really honest man to become a revolutionary, but also showed – even more importantly – what a revolutionary should be like, what his principles should be, how he must achieve his goals, what methods and means he should employ to realise them.9

Nicholas Berdyaev observed that the “Russian revolutionaries who were to be inspired by the ideas of Chernyshevsky present an interesting psychological problem. The best of Russian revolutionaries acquiesced during this earthly life in persecution, want, imprisonment, exile, penal servitude, execution, and they had no hope whatever of another life beyond this. The comparison with Christians of that time is almost disadvantageous to the latter; they highly cherished the blessings of this earthly life and counted upon the blessings of heavenly life.”10

Chernyshevsky, like those who followed him, was passionately committed to the power of reason. His philosophy firmly grounded in the materialist outlook and a sober utilitarianism. But in his life Chernyshevsky was the embodiment of self-abnegation, single-mindedness and asceticism. Like a true saint he asked nothing for himself, but wanted everything for the people as a whole. When the police officers took him into exile in Siberia they said, “Our orders were to bring a criminal and we are bringing a saint. “These two elements, the religious and the secular, the ascetic and the calculating,” writes historian Geoffrey Hosking, “remained in unresolved tension in his personality, but on the level of theory he sought a resolution in the idea of a social revolution to be promoted by the best people on the basis of personal example.”11

Inspired by Chernyshevsky, groups of young radicals emerged committed to the reconstruction of Russia as a federation of village communes and communally run factories. The reading list of one such revolutionary cell is revealing because it included the New Testament and histories of Russian Gnostic communities. The leader of the main radical circle in the Russian capital St. Petersburg spoke of founding “a religion of humanity.” He called his circle “an Order of Knights” and included in its ranks members of a Gnostic “God-manhood sect” which taught that each individual is potentially destined to become a god. It was not uncommon for the revolutionary call “liberty, equality, and fraternity” to be written on crosses, or for Russian revolutionaries to declare their belief in “Christ, St. Paul, and Chernyshevsky.”

The Russian socialists frequently visited religious sectarians and sought their support because of their history of alienation from the tsarist regime. Emil Dillon, an English journalist who had personal contact with several persecuted religious communities, reminds us:

Among the various revolutionary agencies which were at work… the most unpretending, indirect, and effective were certain religious sectarians…. Coercion in religious matters did more to spread political disaffection than the most enterprising revolutionary propagandists. It turned the best spirits of the nation against the tripartite system of God, Tsar, and fatherland, and convinced even average people not only that there was no lifegiving principle in the State, but that no faculty of the individual or the nation had room left for unimpeded growth.12

V.I. Lenin & The Spiritual Underground

Men who are participating in a great social movement always picture their coming action as a battle in which their cause is certain to triumph. These constructions… I propose to call myths; the syndicalist “general strike” and Marx’s catastrophic revolution are such myths.

— Georges Sorel, 1906

Religious sectarians played a significant part in the formation of Bolshevism, V.I. Lenin’s unique brand of revolutionary Marxism. Indeed, Marxism with its aggressive commitment to atheism and scientific materialism, scorned all religion as “the opium of the people.” Yet this did not prevent some Bolshevic leaders from utilising concepts taken directly from occultism and radical Gnosticism. Nor did the obvious materialist outlook of Communism, as Bolshevism became known, stop Russia’s spiritual underground from giving valuable patronage to Lenin’s revolutionary cause.

One of Vladimir Lenin’s early supporters was the radical Russian journalist V. A. Posse, who edited a Marxist journal Zhizn’ (Life) from Geneva. Zhizn’ aimed to enlist the support of Russia’s burgeoning dissident religious communities in the fight to overthrow the tsarist autocracy. Posse’s publishing enterprise received the backing of V.D. Bonch-Bruevich, a Marxist revolutionary and importantly a specialist on Russian Gnostic sects. Through Bonch-Bruevich’s connections to the spiritual underground of Old Believers and Gnostics, Posse secured important financial help for Zhizn’.

The goal of Zhizn’ was to reach a broad peasant and proletarian audience of readers that would some day constitute a popular front against the hated Russian government. Lenin soon began contributing articles to Zhizn’. To Posse, Lenin appeared like some kind of mystic sectarian, a Gnostic radical, whose asceticism was exceeded only by his self-confidence. Both Bonch-Bruevich and Posse were impressed by Lenin’s zeal to build an effective revolutionary party. Lenin disdained religion and showed little interest in the ‘religious’ orientation of Zhizn’. The Russian Marxist thinker Plekhanov, one of Lenin’s early mentors, openly expressed his hostility to the journal’s ‘religious’ bent. He wrote to Lenin complaining that Zhizn’, “on almost every page talks about Christ and religion. In public I shall call it an organ of Christian socialism.”

The Zhizn’ publishing enterprise came to an end in 1902 and its operations were effectively transferred into Lenin’s hands. This led to the organisation in 1903-1904 of the very first Bolshevic publishing house by Bonch-Bruevich and Lenin. Both men viewed the Russian sectarians as valuable revolutionary allies. As one scholar notes, “Russian religious dissent appealed to Bolshevism even before that movement had acquired a name.”13

V.D. Bonch-Bruevich (1873-1955) came to revolutionary Marxism under the influence of the Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy’s social teachings. Like Lenin’s wife Krupskaya, he started his revolutionary career distributing Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God Is within You, a work infused with neo-Gnostic themes. In 1899 Bonch-Bruevich left Russia for Canada to live among the Doukhobors, Russian Gnostic communists whose refusal to pay taxes and serve in the army drove them into exile. Bonch-Bruevich reported on the secret doctrines of the Doukhobors and put in writing their fundamental oral teachings known as the ‘Living Book’. On his return to Europe in 1901 Bonch-Bruevich introduced Lenin to the chief tenets of these Gnostic communists. The Doukhobors, with their radical rejection of the Church and State, with their denial of the uniqueness of the historical Christ, and their neglect of the Bible in favour of their own secret tradition, were of some interest to the founder of Bolshevism.

V.D. Bonch-Bruevich (1873-1955) came to revolutionary Marxism under the influence of the Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy’s social teachings. Like Lenin’s wife Krupskaya, he started his revolutionary career distributing Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God Is within You, a work infused with neo-Gnostic themes. In 1899 Bonch-Bruevich left Russia for Canada to live among the Doukhobors, Russian Gnostic communists whose refusal to pay taxes and serve in the army drove them into exile. Bonch-Bruevich reported on the secret doctrines of the Doukhobors and put in writing their fundamental oral teachings known as the ‘Living Book’. On his return to Europe in 1901 Bonch-Bruevich introduced Lenin to the chief tenets of these Gnostic communists. The Doukhobors, with their radical rejection of the Church and State, with their denial of the uniqueness of the historical Christ, and their neglect of the Bible in favour of their own secret tradition, were of some interest to the founder of Bolshevism.

In 1904 Bonch-Bruevich, with Lenin’s support, began publishing Rassvet (Dawn) in an effort to spread revolutionary Marxism among the religious dissidents. His first editorial attacked all the Russian tsars for their persecution of the Old Believers and sectarians, and stated that the journal’s goal was to report events occurring world wide, “in various corners of our vast motherland, and among the ranks of Sectarians and Schismatics.” Rassvet combined Communist and apocalyptic themes that were both compelling and comprehensible to Russia’s spiritual underground.

By the early years of the twentieth century Russia was in a revolutionary mood. Bonch-Bruevich wrote that this would soon produce a “street battle of the awakened people.” He urged his fellow Communist revolutionaries to use the language of the spiritual underground in persuading the masses that the government was “Satan” and that “all men are brothers” in the eyes of God. He wrote:

If the proletariat-sectarian in his speech requires the word ‘devil’, then identify this old concept of an evil principle with capitalism, and identify the word ‘Christ’, as a concept of eternal good, happiness, and freedom, with socialism.

Communist God-Builders & The Occult

If a newcomer to the vast quantity of occult literature begins browsing at random, puzzlement and impatience will soon be his lot; for he will find jumbled together the droppings of all cultures, and occasional fragments of philosophy perhaps profound but almost certainly subversive to right living in the society in which he finds himself. The occult is rejected knowledge: that is, an Underground whose basic unity is that of Opposition to an establishment of Powers That Are.

— James Webb, Occult Underground

A Marxist pamphlet written before 1917 and later reissued by the Soviet government bluntly declared that man is destined to “take possession of the universe and extend his species into distant cosmic regions, taking over the whole solar system. Human beings will be immortal.” Anatoly Lunacharsky, the first Commissar of Enlightenment in the new Soviet state, believed that as religious conviction had been a great force of change in history, Marxists should conceive the struggle to transform nature through labor as their form of devotion, and the spirit of collective humanity as their god.

A.V. Lunacharsky (1875-1933) and the Russian writer Maxim Gorky (1868-1936), close friends of Vladimir Lenin, were acquainted with a broad spectrum of occult thought, including Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy and Helena Blavatsky’s Theosophy. Both these prominent Bolshevic revolutionaries shared a life-long interest in ancient mystery cults, religious sectarianism, parapsychology and Gnosticism. Maria Carlson maintains that Gorky’s “vision of a New Nature and a New World, subsequently assimilated to its socialist expression as the Radiant Future, is fundamentally Theosophic.”14 Gorky valued the writings of the occultists Emanuel Swedenborg and Paracelsus, as well as those of Fabre d’Olivet and Eduard Schure.

A.V. Lunacharsky (1875-1933) and the Russian writer Maxim Gorky (1868-1936), close friends of Vladimir Lenin, were acquainted with a broad spectrum of occult thought, including Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy and Helena Blavatsky’s Theosophy. Both these prominent Bolshevic revolutionaries shared a life-long interest in ancient mystery cults, religious sectarianism, parapsychology and Gnosticism. Maria Carlson maintains that Gorky’s “vision of a New Nature and a New World, subsequently assimilated to its socialist expression as the Radiant Future, is fundamentally Theosophic.”14 Gorky valued the writings of the occultists Emanuel Swedenborg and Paracelsus, as well as those of Fabre d’Olivet and Eduard Schure.

Drawing on the imagery of the ancient solar mysteries, Gorky declared in Children of the Sun, “we people are the children of the sun, the bright source of life; we are born of the sun and will vanquish the murky fear of death.” In his Confession, the “people” have become God, creators of miracles, possessors of true religious consciousness, and immortal. Gorky envisioned a beautiful future of work for the love of work and of man as “master of all things.” Revealing his familiarity with parapsychology and faith healing, Gorky tells how an assembled crowd uses its collective energy to heal a paralysed girl. He was deeply impressed by research into thought transference, often writing of the “miraculous power of thought”, while expressing the hope that one day reason and science would end fear.

The ideas advanced by Lunacharsky and Gorky became known as God building, described by one researcher as a “movement of secular rejuvenation with mystery cult aspects.”15 God building implied that a human collective, through the concentration of released human energy, can perform the same miracles that were assigned to supra-natural beings. God builders regarded early Christianity as an authentic example of collective God building, Christ being nothing other than the focus of collective human energy. “The time will come,” said Gorky, “when all popular will shall once again amalgamate in one point. Then an invincible and miraculous power will emerge, and God will be resurrected.”16 Years before, Fyodor Dostoyevsky had written in The Possessed, “God is the synthetic personality of the whole people.” According to Mikhail Agursky:

For Gorky, God-building was first of all a theurgical action, the creation of the new Nature and the annihilation of the old, and therefore it coincided fully with the Kingdom of the Spirit. He considered God to be a theurgical outcome of a collective work, the outcome of human unity and of the negation of the human ego.17

Before the Russian Revolution, Lunacharsky’s political propaganda relied heavily on words and images ultimately derived from Russian Gnostics and religious sectarians. In one pamphlet he urged readers to refuse to pay taxes or serve in the army, to form local revolutionary committees, to demand ownership of their land, overthrow the autocracy and replace it with a “brotherly society” of socialism. Indeed, there was as much attention given to Christ as to Marx in Lunacharsky’s writings. “Christianity, in all its forms, even the purest and most progressive,” he wrote, “is the ideology of the downtrodden classes, the hopelessly immobile, those who cannot believe in their own powers; Christianity is also a weapon of exploitation.” But Lunacharsky realised there is also an underground spiritual tradition, the arcane language and symbols of which might be used to mobilise the people to carry out the revolution.

Occult elements are obvious in Lunacharsky’s early plays and poems, including a reference to the “astral spirit”, and a familiarity with white magic and demonology. He discussed Gnosticism, the Logos, Pythagoras, and solar cults in his two volume work Religion and Socialism. After the Bolshevic Revolution, Lunacharsky wrote an occult play called Vasilisa the Wise. This was to be followed by a never published “dramatic poem” entitled Mitra the Saviour, a clear reference to the pre-Christian occult deity. Significantly, it is Lunacharsky, along with the scholar of Russian Gnostic sects V.D. Bonch-Bruevich, who is credited with developing the so-called “cult of Lenin” which dominated Soviet life following the Bolshevic leaders’ death in 1924.

Soviet Power & Spiritual Revolution

A Weltanschauung has conquered a state, and emanating from this state it will slowly shatter the entire world and bring about its collapse. Bolshevism, if unchecked, will change the world as completely as Christianity did. Three hundred years from now it will no longer be said that it is merely a question of organising production in a different way… If this movement continues to develop, Lenin, three hundred years from now, will be regarded not only as one of the revolutionaries of 1917, but as the founder of a new world doctrine, and he will be worshipped as much perhaps as Buddha.

— Adolf Hitler, 193218

In the wake of the total collapse of Imperial Russia and the devastation caused by the First World War, Lenin and the Bolshevics seized power in October 1917. A revolution that would not have been possible without the active support and participation of the Russian spiritual underground. The Bolshevics, in the opinion of one Russian scholar:

most probably would not have been able to take power or to consolidate it if the multimillion masses of Russian sectarians had not taken part in the total destruction brought about by the revolution, which acquired a mystical character for them. To them the state and the church were receptacles of all kinds of evil, and their destruction and debasement were regarded as a mystic duty, exactly as it was with the [medieval Gnostic sects of] Anabaptists, Bogomils, Cathars, and Taborites.19

Ground down by centuries of autocratic tsarist rule as well as the Orthodox Church, its mere appendage, the Russian people came to accept the Communism of Lenin. “Bolshevism is a Russian word,” wrote an anti-Communist Russian in 1919. “But not only a word. Because in that guise, in that form and in those manifestations which have crystallized in Russia… Bolshevism is a uniquely Russian phenomenon, with deep ties to the Russian soul.”20 Even the Nazi propaganda minister Dr. Goebbels, who built his political career fighting Communism, confessed that no tsar had ever understood the Russian people as deeply as Lenin, who gave them what they wanted most – land and freedom.

Lenin wedded the dialectical materialism of Marx to the deep-rooted tradition of Russian socialism permeated as it was by Gnostic, apocalyptic, and messianic elements. In the same manner he reconciled the Marxist commitment to science, atheism and technological progress with the Russian ideas of justice, truth and self-sacrifice for the collective. Similarly the leader of Bolshevism merged the Marxist call for proletarian internationalism and world revolution with the centuries old notion of Russia’s great mission as the harbinger of universal brotherhood. Violently opposed to all religion, atheistic Bolshevism drew much from the spiritual underground, becoming in the words of one of Lenin’s comrades, “the most religious of all religions.”

“Nonetheless we have studied Marxism a bit,” wrote Lenin, “we have studied how and when opposites can and must be combined. The main thing is: in our revolution… we have in practice repeatedly combined opposites.” Several centuries earlier the Muslim Gnostic teacher Jalalladin Rumi pointed out, “It is necessary to note that opposite things work together even though nominally opposed.”

After the 1917 Bolshevic Revolution:

occultism was part of a cluster of ideas that inspired a mystical revolutionism based on the belief that great earthly events such as revolution reflect a realignment of cosmic forces. Revolution, then, had eschatological significance. Its result would be a ‘new heaven and a new earth’ peopled by a new kind of human being and characterized by a new kind of society cemented by love, common ideals, and sacrifice.

The Bolshevic Revolution did not quash interest in the occult. Some pre-revolutionary occult ideas and symbols were transformed along more ‘scientific’ lines. Mingled with compatible concepts, they permeated early Soviet art, literature, thought, and science. Soviet political activists who did not believe in the occult used symbols, themes, and techniques drawn from it for agitation and propaganda. Further transformed, some of them were incorporated in the official culture of Stalin’s time.21

Apocalyptic and mess-ianic themes, popularised for centuries by the Russian spiritual underground, were played out in the Bolshevic Revolution and fueled the drive to build a classless, communist society. The dream of a communist paradise on earth created by human hands, a new world adorned by technological perfection, social justice and brotherhood, was found both in Marx and in the Russian spiritual underground.

Lenin promulgated a law exempting religious sectarians from military service. Writers and poets, drawing inspiration from the Russian religious underground, hailed the Revolution as a messianic, world mystery. One writer compared the Bolshevic Revolution with the origin of Christianity. “Christ was followed,” he exclaimed, “not by professors, nor by virtuous philosophers, nor by shopkeepers. Christ was followed by rascals. And the revolution will also be followed by rascals, apart from those who launched it. And one must not be afraid of this.”

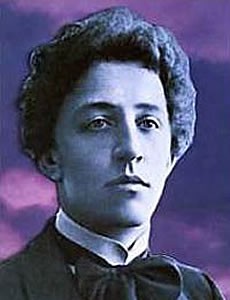

Alexander Blok (1880-1921) was the most important Russian poet to recognise the Bolshevics. A student of Gnosticism, Blok discerned the inner meaning of the tumultuous political and social events. There was a hidden spiritual content at the core of the external upheavals of the Revolution and the bloody Civil War that followed. Blok clearly expressed this in his famous poem The Twelve, where the invisible Christ leads the revolutionary march.

Alexander Blok (1880-1921) was the most important Russian poet to recognise the Bolshevics. A student of Gnosticism, Blok discerned the inner meaning of the tumultuous political and social events. There was a hidden spiritual content at the core of the external upheavals of the Revolution and the bloody Civil War that followed. Blok clearly expressed this in his famous poem The Twelve, where the invisible Christ leads the revolutionary march.

Another Russian poet and occultist, Andrei Bely, a disciple of Steiner’s Anthroposophical movement, hailed the Revolution as the first stage of a far greater cultural and spiritual revolution to come. For Bely, as for his contemporary Blok, the Bolshevic Revolution was above all a powerful theurgical instrument. Andrei Bely (1880-1934) saw theurgy as a means to change the world actively in collaboration with God. In spite of the turmoil and bloodshed, for these Russian occultists the revolution served as an instrument of the new creation. Bely celebrated the 1917 Revolution in a poem, Christ is Resurrected, in which the Bolshevic take over is compared with the mystery of Crucifixion and Resurrection. Rudolf Steiner understood why the Russians welcomed the October Revolution, but criticised Bolshevism as a dangerous mix of Western abstract thinking and Eastern mysticism.

The Russian spiritual underground spawned several important writers and poets who welcomed the Bolshevic Revolution. Two of the most outstanding were Nikolai Kliuev (1887-1937) and Sergei Esenin (1895-1925). Occult images and Russian messianic themes abound in their poems. Kliuev saw Lenin as the popular leader and embodiment of the Old Belief. In typically Gnostic fashion Esenin disdained the old God of the Church and proclaimed a “new Nazareth”. The young Esenin gave support to the Bolshevic Red Army and even tried to join the Bolshevic party. Tragically, Kliuev felt betrayed by the Revolution, was arrested and died on the way to a labor camp in 1937. Esenin took his own life in 1925 believing dark forces had usurped the Russian Revolution.

By the early 1920s the Bolshevics had consolidated their hold over much of the former Russian Empire. The Communist Party emerged as the monolithic embodiment of the popular will. All occult societies, including the Theosophists and Anthroposophists, were disbanded. Freemasonry was virulently condemned and its lodges closed. In the drive to modernise Russia and build a technologically advanced Soviet Union, occult notions were publicly classed as superstition and openly ridiculed. The new Soviet State, with its Marxist-Leninist ideology, became the sole arbitrator of all thought. Leading occult teachers were forced into exile. Yet many of those associated with the spiritual underground joined the Communist Party and found employment in various Soviet organisations.

The sway of the spiritual underground did not disappear. Arcane truths and primordial urges took on new forms in keeping with the new reality. Esoteric ideas were clothed in the language of a new epoch. One writer explains:

In Stalin’s time, occult themes and techniques detached from their doctrinal base became part of the official culture…. The occult themes of Soviet literature of the 1920s were transformed into the magical or fantastic elements that observers have noted in Socialist Realism. Stalin himself was invested with occult powers.22

The Russian thinker, Isai Lezhnev (1891-1955), insisted on the profoundly religious character of Communism, which was “equal to atheism only in a narrow theological sense.” Emotionally, psychologically, Bolshevism was extremely religious, seeing itself as the only custodian of absolute truth. Lezhnev correctly discerned in Bolshevism the rise of a “new religion” which brought with it a new culture and political order. He embraced Marxism-Leninism and welcomed Stalin as a manifestation of the “popular spirit”.

The Russian Revolution, which gave rise to the super power known as the Soviet Union, cast a gigantic shadow over the twentieth century. Bolshevism, the materialistic worldview developed by Vladimir Lenin, left its mark on all aspects of modern thought. And the roots of Lenin’s Communism and the Soviet Union go deep into the ancient secret tradition of humanity.

Was atheistic Bolshevism, for all its worship of science and materialism, the expression of something supra-natural? Many in the spiritual underground passionately believed so. The Gnostic poet Valery Briusov (1873-1924), who joined the Bolshevic party in 1920, had been involved in magick, occultism and spiritualism prior to the revolution. Briusov stressed that Russia’s destiny was being worked out, not on earth, but by mystic forces for which the 1917 Revolution was part of the occult plot.

Another prominent Russian occultist, the acclaimed artist Nicholas Roerich, acknowledged Lenin and Communism as cosmic phenomenon. In 1926 he wrote:

He [Lenin] incorporated and circumspectly fitted every material into the world order. This opened up for him the path into all parts of the world. And people have formed a legend not only as a record of his deeds but also as a mark of his aspirations…. We have seen for ourselves how the nations have understood the magnetic power of communism. Friends, the worst counsellor is negativity. Behind every negation ignorance is concealed.

The philosopher Nicholas Berdyaev, a former Marxist who came to embrace Christian mysticism, was exiled from the Soviet Union in the 1920s. He had studied occultism and was acquainted with many Russian Gnostic sects. His 1909 book The Philosophy of Freedom is full of Gnostic themes. And like the Gnostics, Berdyaev opposed the institution of the family as yoking men and women to “necessity” and the endless chain of birth and death. Writing from exile, more than twenty-five years after the Revolution, Berdyaev observed:

Russian communism is a distortion of the Russian messianic idea; it proclaims light from the East which is destined to enlighten the bourgeois darkness of the West. There is in communism its own truth and its own falsehood. Its truth is a social truth, a revelation of the possibility of the brotherhood of man and of peoples, the suppression of classes, whereas its falsehood lies in its spiritual foundations which result in a process of dehumanisation, in the denial of the worth of the individual man, in the narrowing of human thought…. Communism is a Russian phenomenon in spite of its Marxist ideology. Communism is the Russian destiny, it is a moment in the inner destiny of the Russian people and it must be lived through by the inward strength of the Russian people. Communism must be surmounted but not destroyed, and into the highest stage which will come after communism there must enter the truth of communism also but freed from its element of falsehood. The Russian Revolution awakened and unfettered the enormous powers of the Russian people. In this lies its principle meaning.23

|

The Hammer and Sickle: Occult Symbols? Throughout the twentieth century the hammer and sickle were universally recognised as symbols of communism and the Soviet Union. For millions of people the hammer and sickle symbolised a new political and economic order offering progress, justice and liberty. While countless others looked on the same hammer and sickle as ominous emblems of oppression, hatred and tyranny. |

Footnotes:

1. Benjamin Walker, Gnosticism Its History & Influence

2. James Webb, Occult Underground

3. Maria Carlson, No Religion Higher Than Truth

4. As quoted in Maria Carlson, No Religion Higher Than Truth

5. Acts 2:44-47

6. Mikhail Agursky, The Third Rome

7. James H. Billington, The Icon and the Axe

8. As quoted in James H. Billington, The Icon and the Axe

9. As quoted in Nina Tumarkin, Lenin Lives: The Lenin Cult in Soviet Russia

10. Nicholas Berdyaev, The Russian Idea

11. Geoffrey Hosking, Russia: People and Empire

12. As quoted in Mikhail Agursky, The Third Rome

13. Robert C. Williams, The Other Bolsheviks

14. Maria Carlson, No Religion Higher Than Truth

15. Richard Noll, The Jung Cult

16. Mikhail Agursky, The Third Rome

17. The Occult in Russian and Soviet Culture, edited by Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal

18. As quoted in Hitler’s Words, edited by Gordon Prange

19. Mikhail Agursky, The Third Rome

20. As quoted in Richard Pipes, Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime 1919-1924

21. The Occult in Russian and Soviet Culture, edited by Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal

22. Ibid

23. Nicholas Berdyaev, The Russian Idea

00:05 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : russie, urss, histoire, occultisme, occultisme russe, bolchevisme, communisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook