Carl Schmitt, besides being one of the thinkers of the ‘conservative revolution’ of the interwar Germany, was also notoriously infamous for being a ‘Hitler’s jurist,’ thus one of those important intellectuals who provided the necessary legal framework for the brutish Nazi regime. Yet, our world is seldom such that individuals can be so simply categorized as ‘good’ or ‘evil,’ and Carl Schmitt, has an interesting concept of the political which might give, and gives, contemporary political students and academics a completely new perspective on the sphere of politics.

Carl Schmitt, besides being one of the thinkers of the ‘conservative revolution’ of the interwar Germany, was also notoriously infamous for being a ‘Hitler’s jurist,’ thus one of those important intellectuals who provided the necessary legal framework for the brutish Nazi regime. Yet, our world is seldom such that individuals can be so simply categorized as ‘good’ or ‘evil,’ and Carl Schmitt, has an interesting concept of the political which might give, and gives, contemporary political students and academics a completely new perspective on the sphere of politics.

Indeed, what is politics and its area of interest - the political? I might well continue by countless common definitions like ‘the political is what concerns the state,’ or I might mention the argument of many radical feminists or some of the scholars as Colin Hay (2002, pp. 69) who suggest that ‘everything has the potential to become political’ - even what was considered to be solely a domain of the ‘private’ - as was a few years ago shown in the infamous ‘fox hunting case’ in Britain.

Thus, the ‘classical’ definition of the political perceives politics as an arena - as Politics with the capital ‘P’ (by equating politics with places where is politics being created ~ usually the state, the government. However, many scholars including the ‘communitarians’ Charles Taylor, Michael Walker, Michael Sandel and Alasdair MacIntyre would certainly argue that politics is today also, or even primarily, created outside the national borders of the state - for instance in INGOs, QUANGOs, TNCs and in economic and financial organizations associated with them such as WTO or Bretton Woods institutions). Nevertheless, the second, ‘less traditional’ definition of politics perceives it as a process. When conceived as a process, in terms of application of power, or as of ‘transformatory capacity’ as Anthony Giddens formulates (1981), politics has the potential to emerge in every social location.

Colin Hay specifies:

‘Power … is about context-shaping, about the capacity of actors to redefine the parameters of what is socially, politically and economically possible for others. More formally we can define power … as the ability of actors (whether individual or collective) to “have an effect” upon the context which defines the range of possibilities of others’ (Hay, 1997, p. 50; quoted in Hay, 2002, p. 74)

Therefore, politics as a process is about power relations between various social actors. By the moment when one actor is able to shape the destiny - behaviour - of another, one talks according to the feminists and Hay about politics. For instance, the fox hunting in Britain was by these terms initially a social activity just as any other (such as for example going shopping, or eating in a restaurant), but by the moment the Labour government issued the ban on hunting the foxes, it pushed it from the social sphere onto the political agenda. Power relations suddenly emerged between the actor (the government in this case) and the British people and interest groups concerned. The whole-national discussion that emerged, with various groups formulated arguing on pros and cons of the ban on fox hunting was thus an excellent example of a process of creating from a formerly ‘innocent’ aspect of social life highly controversial political topic involving heated discussion of many individuals and organizations.

of another, one talks according to the feminists and Hay about politics. For instance, the fox hunting in Britain was by these terms initially a social activity just as any other (such as for example going shopping, or eating in a restaurant), but by the moment the Labour government issued the ban on hunting the foxes, it pushed it from the social sphere onto the political agenda. Power relations suddenly emerged between the actor (the government in this case) and the British people and interest groups concerned. The whole-national discussion that emerged, with various groups formulated arguing on pros and cons of the ban on fox hunting was thus an excellent example of a process of creating from a formerly ‘innocent’ aspect of social life highly controversial political topic involving heated discussion of many individuals and organizations.

So far, however, these definitions of the political as either what ‘happens in the government’ or as a ‘process of application of power’ are very standard, or even ‘boring.’ Boring in a sense that these conceptions of what politics is, of what the political contains, have become almost universally accepted, and underline many other academic works without even being contested from any different perspective.

Now enters Carl Schmitt, who poses a cardinal question - ‘what is all that for?’ Indeed, what is the aim, the goal, of politics? Aristotle mentions in the Nicomachean Ethics is the ‘master art’ (Book I, §2) since it uses knowledge of all other arts and hence its fundamental goal - the goal of a politician - should be to produce ‘good citizens’ (Book I, §13), while the law of a polis should be the framework to show what this good is. Again, argument being that a politician is someone who has achieved experience and knowledge in all aspects of life besides being endowed with the best abilities. Aristotle tells that only such a ‘mature’ person can engage in politics and thus be able to judge ‘what the good is.’ (Book I, §3) Hence, according to Aristotle, the laws of a polis are also moral laws, and to act according to these laws is equated to being ‘just.’

Nicomachean Ethics is the ‘master art’ (Book I, §2) since it uses knowledge of all other arts and hence its fundamental goal - the goal of a politician - should be to produce ‘good citizens’ (Book I, §13), while the law of a polis should be the framework to show what this good is. Again, argument being that a politician is someone who has achieved experience and knowledge in all aspects of life besides being endowed with the best abilities. Aristotle tells that only such a ‘mature’ person can engage in politics and thus be able to judge ‘what the good is.’ (Book I, §3) Hence, according to Aristotle, the laws of a polis are also moral laws, and to act according to these laws is equated to being ‘just.’

Very interestingly, the reader will see how close Aristotle and Carl Schmitt in their argument on the political are. Aristotle’s fundamental content of politics is as mentioned above to distinguish between the ‘right and wrong.’ On the other hand Carl Schmitt, in the Concept of the Political, postulates that every domain of life rests on its own distinctions; for economics it is ‘profitable and unprofitable,’ or for morality it is ‘good and evil.’ Schmitt then continues that for the political its fundamental activity is to distinct between ‘friend and enemy’ (1996, p. 27). Schmitt in his book develops a powerful theory and he states that if one empirically studies history the striking fact is that every political grouping can be distinguished as such because it organizes itself on the basis of the friend-enemy distinction.

In this sense, first human associations as primitive tribes of our ancestors, were the first political organizations because they organized people into a unit - a tribe - and their allies (’friends’) against other such groupings - other ‘tribes’ - which might pose a threat to their existence. It is irrelevant whether one conceives of this as of form of ‘contract’ between tribesmen in the sense of Locke or Hobbes or in the Nietzschean or Spenglerian sense where the organizers of this political association are the members of a warrior caste. The important fact is that behind the idea of any political organization - behind the organized political community - is the necessity to distinct in the concrete sense between friend and enemy. The similarity between the ‘right and wrong’ of Aristotle and Schmitt’s ‘friend-enemy’ dichotomy is now obvious and Schmitt is also very close to Spengler, who equated the emergence of first communities with the necessity to form a group united in achieving one common goal (1976, Ch. 4).

Note that it is interesting that Colin Hay is unfamiliar or does not mention Carl Schmitt in his Political Analysis, since their line of thought is very reminiscent of each other. Schmitt just as Hay develops his argument by stating that every social aspect - religions, morality, economics, arts can become the political. However, while Hay equates the shift from the social to political with the ability to make a specific issue a topic of the national discussion or of a governmental debate, Schmitt specifies this by arguing that what every  grouping in fact does is to specifying its enemies and organizing its friends.

grouping in fact does is to specifying its enemies and organizing its friends.

The feminists therefore group themselves into various interest groups and draw support for their arguments from various think tanks, academics (’friends’) in order to ’struggle’ against their perceived enemies - masculine social institutions perhaps. In similar vein, while workers doing their job in a factory do no belong to the political sphere, by the moment they organize themselves into a labour union, they become a political organization. They form a collectivity of ‘friends’ as against what is the other, the alien - the enemy - in this case, entrepreneurs or the state, in order to reach their goal - again, the increase of wages perhaps. Similarly, for Schmitt religion communities are not political when they worship their saints and go to pray into churches, but when they organize themselves to fight against other religion communities (immediately, the Christian crusades against the ‘infidels’ comes to mind) they become the political by the very nature of forming the friend-enemy distinction.

Every such grouping has its own means how to fight ‘traitors’ in its own ranks who do not accept the group’s idea of friend-enemy. Again, the best example is provided by mentioning the Roman Church, where those who do not ‘believed in God’ were marked as witches and burned by the Inquisition.

Implications of Schmitt’s definition of the political on the basis of ‘friend and enemy’ distinction are tremendous. Using this concept of the political it is immediately possible, just as Schmitt notes, to distinguish that supposedly ‘apolitical’ liberal society is political in its very nature. Even though that in liberal society one is supposedly able ‘to live a life one chooses’ in fact one has to live a life in the liberal free market society. Thus, indigenous people whose land and local businesses is being taken away by transnational companies, is not obviously burned at stakes of the Inquisition, but the liberal society has other means to fight these ‘infidels’ who prefer to live their life in their community, do not want to watch TV, and do not want to shop in the Wal-Mart. Simply, these can either accommodate or they are left to starve.

In liberal thought, the friend is the one who accepts the implication that the society is one gigantic free market, atomic community of people who fight all against all and only the ‘best’ is able to survive (but in fact, it is necessary to understand that this the ‘best’ only in one sense - in the Liberal sense - as formulated by Adam Smith and daily repeated by neo-liberals - the best is according to it ‘the most economic’). Traditions, agriculture, companies, or even fairy tales of local communities and indigenous people all around the world is thus taken away by what was supposed to be found the ‘best’ by the market. Thus, today for everyone the best traditions are the traditions that ‘proven to be’ the best by the rising global market - i.e. consumerism, the best agriculture ‘is’ to cease one’s lands to foreign trans-national corporations, let your own neighbours to be employed for laughtable wages and import barley from countries which produce ‘the best barley in the world.’ Similarly the ‘best companies’ are not local companies, the ‘best companies’ are gigantic trans-national corporations who are able to destroy every competition by their aggressive prize policy. And ultimately, regional and national myths and stories are being supplanted by the ‘best fairy tales’ from Disney or Warner Bros.

Implications of the world conceived by Liberal thinkers, global financial institutions and large businesses could thus well be rather sarcastically summarized as ‘compete, export or die.’

The political entity ceases to one only if it renounces its claim to choose friend and enemy and how they should be treated. Most importantly, Schmitt, continues, the universalist tendencies of Liberalism to announce that it fights for the ’cause of humanity,’ do not presuppose the end of politics and friend-enemy distinctions. Indeed, this even leads to even more extreme forms of friend-enemy dichotomy, even to the ‘total war,’ since those who fight against Liberal universalist tendencies supposedly fight against humanity itself.

Schmitt explains:

‘When a state fights its political enemy in the name of humanity, it is not a war for the sake of humanity, but a war wherein a particular state seeks to usurp a universal concept against its military opponent. At the expense of its opponent, it tries to identify itself with humanity in the same way as one can misuse peace, justice, progress, and civilization in order to claim these as one’s own and to deny the same to the enemy.’ (1994, p. 54)

The extreme form can be most notably perceived in Kant, who famously formulated his ‘categorical imperative,’ thus identifying his cause with the cause of humanity itself. The word humanity, or any other similar concepts as justice, freedom, peace, progress can be thus easily used to justify imperialist expansion. But in fact, as De Maistre mentioned:

‘(…) there is no such thing as man in the world. In my lifetime I have seen Frenchmen, Italians, Russians, etc.; thanks to Montesquieu, I even know that one can be Persian. But as for man, I declare that I have never in my life met him; if he exists, he is unknown to me.’ (1994, p. 53)

To argue that one’s ideas are universally applicable as the ideas of enlightened thinkers did, and as of other contemporary Liberal do, is according to Carl Schmitt to create the ultimate dichotomy between friend and enemy. It leads to extreme forms of opposition against those who deny their applicability. Schmitt summarizes in the following words:

‘To confiscate the word humanity, to invoke and monopolize such a term probably has certain incalculable effects, such as denying the enemy the quality of being human and declaring him to be an outlaw of humanity; and a war can thereby be driven to the most extreme inhumanity.’ (1996, p. 54)

Those who oppose are thus ‘monsters,’ they oppose their ‘own kind,’ they oppose ‘humanity’ itself, and are thus ‘unworthy’ of any human treatment.

But ultimately, what does Liberalism fights for, who are its ‘friends’?

‘Every encroachment, every threat to individual freedom and private property and free competition is called repression and is eo ipso something evil. What this liberalism still admits of state, government, and politics is confined to securing the conditions for liberty and eliminating infringements on freedom.’ (1996, p. 71)

Thus as Dr. Karl Polanyi showed in Great Transformations (1967), the modern liberal state and the interest of business goes hand in hand, indeed, they are inseparable. To conclude, one has to put Liberalism into a historical perspective, which offers a full justification for its friend-enemy dichotomy. Liberalism, and its enlightened predecessors stood in opposition to the feudal system and absolutism of the 18th century. They represented the ideals of the rising middle class - merchants and businessmen whose interests and economic activities were being threatened by the power of the state. Therefore ‘friends’ - bourgeoisie - middle class of merchants and and first entrepreneurs stood against its enemy - the aristocracy and absolutist state.

This is obviously not to say that Liberals are ‘evil,’ quite contrary, they had proven at the time to be the most powerful political force which was able to form the most powerful political grouping of ‘friends’ supported by the Liberal thought. Thus, the argument that they represent an ‘apolitical force’ is from this perspective fundamentally flawed. But as was mentioned earlier, life is diversity, it is dichotomy of people, groups and interests. Interests of some groups are not the interests of others. The claim that Liberalism represents the interests of all humanity is thus only a ‘noble lie’ in the Platonian sense, which has as its purpose to secure such interests in power or to elevate them into such position.

The belief of this author is that the interests of peoples - of cultures - of their traditions and daily life - cannot be equated with the interests of large business. It is thus necessary to refute the universalist tendencies of Liberalism and portray them in the perspective which clearly shows them as one of many ideas how the social life should be organized and as representing only the interests of the particular class and not of ‘humanity.’

******

Bibliography:

Aristotle. (1999) Nicomachean Ethics (W. D. Ross, Trans.). Kitchener: Batoche Books.

Giddens, A. (1981) A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism. London: Macmillan Press.

Hay, C. (1997) ‘Divided by a Common Language: Political Theory and the Concept of Power,’ Politics, 17(1), pp. 45-52.

Hay, C. (2002) Political Analysis. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Maistre, J. d. (1994) Considerations on France. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Polanyi, K. (1967) The Great Transformation. Boston: Beacon Press.

Schmitt, C. (1996) The Concept of the Political. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Spengler, O. (1976) Man and Technics. New York: Greenwood Press.

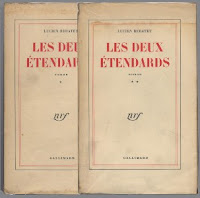

Novopress, 5/2/2009 : "Les Deux étendards, chef d’œuvre classique et maudit.

Novopress, 5/2/2009 : "Les Deux étendards, chef d’œuvre classique et maudit.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg