jeudi, 17 juillet 2014

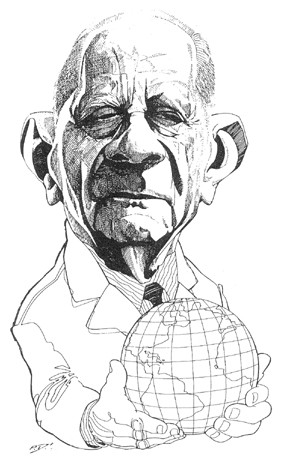

Carl Schmitt on the Tyranny of Values

Carl Schmitt on the Tyranny of Values

By Greg Johnson

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

Carl Schmitt’s two essays on “The Tyranny of Values” (1959 [2] and 1967 [3]) are typical of his work. They contain simple and illuminating ideas which are nevertheless quite difficult to piece together because Schmitt presents them only through complex conversations with other thinkers and schools of thought. In “The Tyranny of Values” essays, Schmitt’s target is “moralism,” which boils down to doing evil while one thinks one is doing good.

Carl Schmitt’s two essays on “The Tyranny of Values” (1959 [2] and 1967 [3]) are typical of his work. They contain simple and illuminating ideas which are nevertheless quite difficult to piece together because Schmitt presents them only through complex conversations with other thinkers and schools of thought. In “The Tyranny of Values” essays, Schmitt’s target is “moralism,” which boils down to doing evil while one thinks one is doing good.

Schmitt is an enemy of political moralism because he thinks it has profoundly immoral consequences, meaning that it creates a great deal of needless conflict and suffering. Schmitt defends a somewhat amoral political realism because he thinks that its consequences are actually moral, insofar as it reduces conflict and suffering.

In Schmitt’s view, one of the great achievements of European man was to subject war to laws [4]. Schmitt calls this “bracketed” warfare. Wars had to be lawfully declared. They were fought between uniformed combatants who displayed their arms openly, were subject to responsible commanders, and adhered to the rules of war. Noncombatants and their property were protected. Prisoners were taken. The wounded were cared for. Neutral humanitarian organizations were respected. And wars could be concluded by peace treaties, because the aims of war were limited, and the enemy and his leaders were not criminalized or proscribed, but recognized as leaders of sovereign peoples with whom one could treat.

Schmitt makes it clear that the rules of war are something different from Christian “just war” theory. Bringing justice or morality into wars actually intensifies rather than moderates them. Indeed, the classical rules of war were quite cynical about morality and justice. Wars could be launched out of crude self-interest, but they could be terminated out of crude self-interest too. Leaders may not have been good enough to avoid wars, but neither were they bad enough that the war had to be prosecuted until their destruction. All parties recognized that if they were scoundrel enough to make war, they were also decent enough to make peace. But by limiting the intensity and duration of wars, this cynicism ended up serving a higher good.

Of course the ideal of “bracketed warfare” had its limits. It did not apply in civil wars or revolutions, since in these both parties deny the legitimacy or sovereignty of the other. Nor did it apply in colonial or anti-colonial wars, primarily fought against nonwhites, and the barbarism also spilled over to the treatment of rival European colonizers. Furthermore, within Europe herself, the ideal of bracketed warfare was often violated. But the remarkable thing is not that this ideal was violated—which is merely human—but that it was upheld in the first place.

If, however, war is moralized, then our side must be good and their side must be evil. Since reality is seldom so black and white, the first necessity of making war moral is to lie about oneself and one’s enemy. One must demonize the enemy while painting one’s own team as innocent and angelic victims of aggression. This is particularly necessary in liberal democracies, which must mobilize the masses on the basis of moralizing propaganda. In a fallen world, moralists are liars.

But the conviction that one is innocent and one’s enemy is evil licenses the intensification of conflict, for all the rules of bracketed warfare now seem to be compromises with evil. Furthermore, even though a negotiated peace is the swiftest and most humane way to end a war, if one’s enemy is evil, how can one strike a bargain with him? How can one accept anything less than complete and unconditional surrender, even though this can only increase the enemy’s resistance, prolong the conflict, and increase the suffering of all parties?

War can be moralized by religious or secular aims. But whether one fights in the name of Christ or Mohammed, or in the name of liberty, equality, and fraternity, the result is to prolong and intensify conflict and suffering.

Moralism, however, is destructive in the political realm as a whole, not just in war (which is merely politics by other means). In “The Tyranny of Values,” Schmitt is concerned with the injection of morality into the legal realm. But we must understand that Schmitt does not oppose moralizing law because he thinks that the law should be amoral or immoral. Instead, Schmitt thinks that the law is already sufficiently moral, insofar as it is capable of reducing conflict in society. Schmitt opposes the introduction of value theory into law because he thinks that it will increase social conflict, thus making the law less moral.

Schmitt’s argument is clearest in the 1959 version [2] of “The Tyranny of Values,” which was a talk given to an audience of about 40 legal theorists, philosophers, and theologians on October 23, 1959, in the village of Ebrach, Bavaria. Later, Schmitt had 200 copies of the paper printed up for distribution among friends and colleagues.

Schmitt points out that value theory emerged at the end of the 19th century as a response to the threat of nihilism. Up until that time, moral philosophy, politics, and law had managed to muddle through without value theory. But when the possibility of nihilism was raised, it seemed necessary to place values on a firm foundation. The three main value theorists Schmitt discusses are the sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920), who holds that values are subjective, and philosophers Nicolai Hartmann (1882–1950) and Max Scheler (1874–1928), who defended the idea of objective values.

Although many people believe that value relativism leads to tolerance, Schmitt understood that relativism leads to conflict:

The genuinely subjective freedom of value-setting leads, however, to an endless struggle of all against all, to an endless bellum omnium contra omnes. In such circumstances, the very presuppositions about a ruthless human nature on which Thomas Hobbes’ philosophy of the state rests, seem quite idyllic by comparison. The old gods rise from their graves and fight their old battles on and on, but disenchanted and, as we today must add, with new fighting means that are no longer weapons, but rather abominable instruments of annihilation and processes of extermination, horrible products of value-free science and of the technology and industrial production that follow suit. What for one is the Devil is God for the other. . . . It always happens that values stir up strife and keep enmity alive.

But Schmitt argues that objective values are not the solution to the conflicts created by subjective values:

Have the new objective values dispelled the nightmare which, to use Max Weber’s words, the struggle of valuations has left in store for us?

They have not and could not. To claim an objective character for values which we set up means only to create a new occasion for rekindling the aggressiveness in the struggle of valuations, to introduce a new instrument of self-righteousness, without for that matter increasing in the least the objective evidence for those people who think differently.

The subjective theory of values has not yet been rendered obsolete, nor have the objective values prevailed: the subject has not been obliterated, nor have the value carriers, whose interests are served by the standpoints, viewpoints, and points of attack of values, been reduced to silence. Nobody can valuate without devaluating, revaluating, and serving one’s interests. Whoever sets a value, takes position against a disvalue by that very action. The boundless tolerance and the neutrality of the standpoints and viewpoints turn themselves very quickly into their opposite, into enmity, as soon as the enforcement is carried out in earnest. The valuation pressure of the value is irresistible, and the conflict of the valuator, devaluator, revaluator, and implementor, inevitable.

A thinker of objective values, for whom the higher values represent the physical existence of the living human beings, respectively, is ready to make use of the destructive means made available by modern science and technology, in order to gain acceptance for those higher values. . . . Thus, the struggle between valuator and devaluator ends, on both sides, with the sounding of the dreadful Pereat Mundus [the world perish].

Schmitt’s point is that a theory of objective values must regard all contrary theories as false and evil and must struggle to overcome them, thus prolonging rather than decreasing social conflict. This is the meaning of “the tyranny of values.” Once the foundations of values have been challenged, conflict is inevitable, and the conflict is just as much prolonged by conservative defenders of objective values as by their subjectivistic attackers: “All of Max Scheler’s propositions allow evil to be returned for evil, and in that way, to transform our planet into a hell that turns into paradise for value.”

What, then, is Schmitt’s solution? First he offers an analogy between Platonic forms and moral values. Platonic forms, like moral values, cannot be grasped without “mediation”:

The idea requires mediation: whenever it appears in naked directness or in automatical self-fulfillment, then there is terror, and the misfortune is awesome. For that matter, what today is called value must grasp the corresponding truth automatically. One must bear that in mind, as long as one wants to hold unto the category of “value.” The idea needs mediation, but value demands much more of that mediation.

Recall that Schmitt is addressing legal theorists. His recommendation is that they abandon value theory, which is an attempt to grasp and apply values immediately and which can only dissolve civilization into conflict. He recommends instead that they return to and seek to preserve the existing legal tradition, which mediates and humanizes values.

In a community, the constitution of which provides for a legislator and a law, it is the concern of the legislator and of the laws given by him to ascertain the mediation through calculable and attainable rules and to prevent the terror of the direct and automatic enactment of values. That is a very complicated problem, indeed. One may understand why law-givers all along world history, from Lycurgus to Solon and Napoleon have been turned into mythical figures. In the highly industrialized nations of our times, with their provisions for the organization of the lives of the masses, the mediation would give rise to a new problem. Under the circumstances, there is no room for the law-giver, and so there is no substitute for him. At best, there is only a makeshift which sooner or later is turned into a scapegoat, due to the unthankful role it was given to play.

What Schmitt refers to obliquely as a “makeshift” in the absence of a wise legislator is simply the existing tradition of jurisprudence. This legal tradition may seem groundless from the point of view of value theorists. But it nevertheless helps mediate conflicts and reduce enmity, which are morally salutary results, and in Schmitt’s eyes, this is ground enough for preserving and enhancing it.

In the expanded 1967 version [3] of “The Tyranny of Values” the already vague lines of Schmitt’s argument are further obscured by new hairpin turns of the dialectic. But the crucial distinction between abstract value theory and concrete legal traditions is somewhat clearer. My comments are in square brackets:

The unmediated enactment of values [basing law on value theory] destroys the juridically meaningful implementation which can take place only in concrete forms, on the basis of firm sentences and clear decisions [legal traditions]. It is a disastrous mistake to believe that the goods and interests, targets and ideals here in question could be saved through their “valorization” [the foundations provided by value theory] in the circumstances of the value-freedom of modern scientism. Values and value theory do not have the capacity to make good any legitimacy [they do not provide foundations for jurisprudence]; what they can do is always only to valuate. [And valuation implies devaluation, which implies conflict.]

The distinction between fact and law, factum and jus, the identification of the circumstances of a case, on the one hand, appraisement, weighing, judicial discovery, and decision, on the other, the discrepancies in the report and the votes, the facts of the case and the reasons for decision, all that has long been familiar to the lawyers. Legal practice and legal theory have worked for millennia with measures and standards, positions and denials, recognitions and dismissals.

Legal tradition is founded on thousands of years of problem-solving and conflict resolution. It needs no other foundation. Value theory adds nothing to law, and it has the potential to subtract a great deal by increasing social conflict and misery. Schmitt’s “The Tyranny of Values” essays thus fall into the skeptical tradition of conservative social theory founded by David Hume, which argues that evolved social traditions are often wiser than theorists offering rational critiques — or rational foundations.

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2014/07/carl-schmitt-on-the-tyranny-of-values/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Croesus-and-Solon-1624-xx-Gerrit-van-Honthorst.jpg

[2] 1959: http://www.counter-currents.com/2014/07/the-tyranny-of-values-1959/

[3] 1967: http://www.counter-currents.com/2014/07/the-tyranny-of-values-1967/

[4] subject war to laws: http://www.counter-currents.com/2012/07/the-political-soldier-carl-schmitts-theory-of-the-partisan/

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : carl schmitt, philosophie, philosophie politique, théorie politique, sciences politiques, politologie, révolution conservatrice, catholicisme, nomocratie, tyrannie des valeurs, allemagne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les commentaires sont fermés.