jeudi, 07 mai 2015

Signez la pétition de soutien à Robert Ménard !

Signez la pétition de soutien à

Robert Ménard !

Paris, mai 2015

Madame, Monsieur,

Face au déchainement médiatique orchestré par le gouvernement de François Hollande et de Manuel Valls,

Au nom de la liberté d’expression,

Parce que le thème de l’immigration et ses conséquences ne doit plus être un tabou,

Apportez votre soutien à Robert Ménard et à la municipalité de Béziers en signant la pétition mise en ligne par Boulevard Voltaire.

Merci.

17:04 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (6) | Tags : actualité, france, béziers, robert ménard |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Le retour de l'Etat?

Le retour de l’État ?...

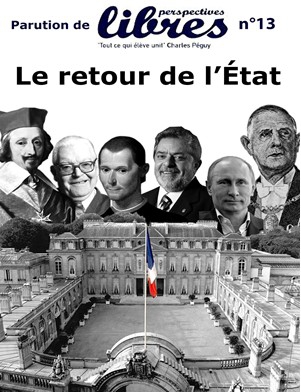

Nous vous signalons la publication du treizième numéro de la revue Perspectives libres consacré au retour de l’État.

La revue Perspectives libres, dirigée par Pierre-Yves Rougeyron, est publiée sous couvert du Cercle Aristote et est disponible sur le site de la revue

Au sommaire :

Éditorial

Le retour de l’État par Pierre-Yves Rougeyron

Dossier : Le retour de l’État

Les métamorphoses de l’État par Hervé Juvin

Le retour de l’État par Wolfgang Drechsler

Pour une métapolitique de l’État par Romain Lasserre

L’État de Grâce par Jérémy-Marie Pichon

La naissance du nouveau monde par Miguel Guenaire

L'espace et l’État par Jacques Blamont

Pour une nouvelle planification par Alain Cotta

L’État-nation : toujours au poste par Alasdair Roberts

Étatisme et socialisme par Julien Funnard

L’État-Tiers par Jean-François Gautier

Libres pensées

« L'autre canon » : histoire de la science économique à la Renaissance par Erik S. Reinert

Management : une époque « formidable » ?... par Philippe Arondel

Libres propos

« Ready for Hillary » : vers un Dernier Moment Américain ? par Clément N'Guyen

La criminalité chinoise organisée par Horacio Calderon

Espagne-Europe : une relation paradoxale par Miguel Ayuso

Camus philosophe : l'enfant et la mort par Pierre Le Vigan

L'économie selon Houellebecq par Pierre Le Vigan

00:05 Publié dans Revue, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : état, étatisme, politologie, sciences politiques, théorie politique, philosophie, philosophie politique, revue |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Choses sales excellentes pour la santé

Choses sales excellentes pour la santé

Les allergies sont provoquées par une réaction excessive du système immunitaire.

Convaincu qu'il est attaqué par de dangereux microbes, notre corps fait tout ce qu'il peut pour s'en débarrasser : il nous fait éternuer pour nettoyer nos poumons et nos fosses nasales, il produit du mucus qui s'écoule abondamment par notre nez, il nous fait pleurer pour nettoyer nos yeux, provoque une inflammation entraînant des rougeurs sur la peau et de la conjonctivite (yeux qui grattent) pour détruire les agents étrangers.

Ces réactions sont provoquées par un puissant cocktail d'histamines, de leucotriènes et de prostaglandines fabriquées par les mastocytes, des cellules du système immunitaire qui se trouvent sur nos muqueuses et qui servent à détecter les agents étrangers.

Mais nos mastocytes se trompent ! Nous ne sommes pas attaqués par un dangereux microbe, mais par d'innocents grains de pollen, poils de chats ou autres poussières.

Pour lutter contre les allergies, notre corps doit donc apprendre à distinguer les corps étrangers dangereux de ceux qui ne le sont pas.

Or, il ne peut apprendre que s'il est souvent confronté à une grande diversité de microbes.

L'hygiène excessive le prive d'occasions nécessaires de s'exercer.

C'est là une raison possible de la forte augmentation des allergies dans les sociétés industrialisées. À force de vouloir tout nettoyer, désinfecter, stériliser, nous avons déboussolé notre système immunitaire.

Alors qu'arrive le printemps et que s'annoncent les premières vagues de pollen, voici quelques découvertes récentes tout à fait passionnantes qui vous aideront à mieux lutter contre les allergies.

Le lave-vaisselle favorise les allergies

Des chercheurs de l'université de Gothenburg, en Suède, ont récemment découvert que les enfants élevés dans des maisons sans lave-vaisselle ont deux fois moins d'allergies que les autres.

Ils avaient beaucoup moins de tendance à l'eczéma, à l'asthme et au rhume des foins.

Cela pourrait être dû au fait que le lave-vaisselle chauffe à très haute température, bien plus fort que la chaleur que nous pouvons supporter en lavant notre vaisselle à la main.

Les ustensiles de cuisine sortent donc largement stérilisés du lave-vaisselle. La plupart des microbes ont été éliminés.

Les personnes qui mangent avec ces ustensiles sont donc moins exposées aux bactéries et autres antigènes (corps étrangers provoquant une réaction immunitaire). Leur système immunitaire est moins sollicité, il perd de sa précision et risque plus souvent de se tromper, de réagir alors que c'est inutile (provoquant des allergies).

Les aliments fermentés et les produits de la ferme diminuent le risque d'allergie

Les enfants qui mangent des aliments fermentés et des produits de la ferme non pasteurisés (beurre, fromage, lait), des fruits et des légumes ramassés tels quels et non traités, ont aussi moins d'allergies que les autres.

On peut là aussi faire un lien avec les bactéries et microbes avec lesquels les enfants sont en contact, et qui leur font un vaccin naturel.

Les recherches montrent que les femmes qui prennent des probiotiques (bactéries bonnes pour la santé) durant leur grossesse ont des enfants plus résistants aux allergies.

Les enfants qui prennent des probiotiques quotidiennement voient leur risque d'eczéma baisser de 58 %.

Concernant les aliments frais de la ferme, les enfants qui grandissent dans des intérieurs aseptisés, sans être en contact ni avec les animaux, ni avec la terre, les insectes, les plantes, les fleurs, les pollens, ont plus de risques de souffrir d'asthme et de rhume des foins que ceux qui vivent dans des maisons un peu sales.

Dans une étude, les enfants d'âge scolaire buvant du lait cru ont eu 41 % de risques en moins d'avoir de l'asthme, et 50 % de risques en moins d'avoir le rhume des foins que les enfants qui buvaient du lait UHT.

Autres choses « sales » qui peuvent être bonnes pour la santé

Notre société est obsédée par la propreté, en particulier pour les enfants. Mais il devient de plus en plus clair que le contact avec la nature, avec les choses naturelles considérées comme sales, est bon et sans doute même essentiel pour maintenir le corps en bon ordre de fonctionnement.

Un biochimiste de l'université du Saskatchewan au Canada a été jusqu'à prétendre, par exemple, que les crottes de nez, ou mucus nasal, ont un goût sucré afin de donner envie de les manger !

En faisant cela, selon lui, les enfants introduisent des microbes pathogènes dans leur organisme. Ils stimulent alors leur système immunitaire, ce qui renforce leurs défenses naturelles.

Et il existe bien d'autres facteurs associés à une baisse des allergies : le fait d'avoir un chien ou des animaux domestiques ; le fait pour un bébé d'aller à la garderie avant l'âge de 1 an, le fait, encore, de recevoir un extrait d'acariens et d'autres allergènes deux fois par jour entre l'âge de 6 mois et 18 mois.

Les acariens sont un des allergènes les plus répandus. Ils déclenchent fréquemment les symptômes de l'asthme. Mais le contact régulier avec les acariens réduit l'incidence des allergies de 63 % chez les enfants à haut risque, dont les deux parents sont allergiques.

Des chercheurs ont aussi constaté que les bébés citadins exposés aux cafards, aux souris, aux acariens et à d'autres allergènes dans la poussière de la maison durant la première année de leur vie avaient moins de risques de souffrir d'allergies à l'âge de 3 ans.

La conclusion est claire : l'environnement est un facteur important d'allergie. Un enfant qui grandit dans une maison trop propre et éloignée de la nature souffrira d'un manque de stimulation de son système immunitaire.

Les bébés qui mangent de la cacahuète ont moins de risques d'allergie à la cacahuète

Entre 1 et 3 % des enfants en Europe occidentale, Australie et Etats-Unis, sont allergiques aux cacahuètes. Il est donc classique de conseiller aux parents de ne pas donner aux jeunes enfants de produits contenant de la cacahuète (arachides).

L'allergie aux cacahuètes est aussi en train de se répandre en Asie et en Afrique. Les réactions allergiques à la cacahuète peuvent varier en gravité, allant de difficultés à respirer au gonflement de la langue, des yeux et du visage, des douleurs d'estomac, des nausées, des démangeaisons et, dans les cas les plus graves, un choc anaphylactique pouvant conduire à la mort.

Cependant, une récente étude indique qu'éviter les cacahuètes dans l'enfance pourrait justement favoriser l'apparition des allergies. Les enfants qui, entre l'âge de 4 et 11 mois, ont reçu des aliments contenant de la cacahuète plus de 3 fois par semaine ont eu 80 % de risques en moins de développer une allergie à la cacahuète, par rapport à ceux qui n'en avaient jamais reçu.

Même chez les petits qui manifestaient déjà des signes d'allergie à la cacahuète, les chercheurs ont réussi à guérir l'allergie en donnant de toutes petites quantités de cacahuète et en augmentant progressivement la dose.

Notez bien que les cacahuètes entières doivent absolument être évitées avec les nourrissons qui risquent de s'étouffer. L'idéal est de donner aux enfants du beurre de cacahuète (peanut butter) en petites quantités.

Je me permets néanmoins de souligner que les cacahuètes sont loin d'être un aliment idéal. Je ne les recommande certainement pas pour nourrir les petits enfants. Le but de l'opération est uniquement d'éviter plus tard une allergie gênante mais aussi dangereuse.

Faites la vaisselle à la main… et autres conseils pour réduire le risque d'allergie

Si la théorie de l'hygiène est vraie, et les données s'accumulent dans ce sens, vous auriez intérêt à faire régulièrement la vaisselle à la main. Souvenez-vous simplement que la plupart des lave-vaisselle doivent être utilisés au moins une ou deux fois par mois pour éviter que certaines pièces ne se dessèchent et endommagent la machine.

Vous pouvez aussi éviter de devenir « trop propre », et ainsi aider à renforcer et réguler vos réactions immunitaires naturelles, en :

- laissant vos enfants se salir. Laissez-les jouer dehors, gratter dans la terre, jouer avec des vers de terre, des insectes, des racines. Même s'ils mangent leurs crottes de nez, ce n'est pas la fin du monde.

- Lorsque vous faites le ménage, contentez-vous régulièrement de faire la poussière, sans utiliser de produit désinfectant ou nettoyant.

- Evitez les savons antibactériens et les autres produits ménagers qui désinfectent de façon trop brutale (eau de javel par exemple). Votre corps a besoin d'être exposé aux micro-organismes. Le simple savon et l'eau chaude suffisent amplement à vous laver les mains. Les antibactériens chimiques comme le triclosan sont très toxiques et favorisent la croissance de bactéries dangereuses.

- Evitez les antibiotiques inutiles. Souvenez-vous que les antibiotiques sont inefficaces contre les infections virales (donc la plupart des rhumes, rhinites, grippes, gastro, otites) ; ils ne marchent que contre les infections bactériennes.

- Mangez des produits bio, si possible que vous aurez cultivés vous-même dans votre potager, avec du bon compost et du bon fumier pleins de micro-organismes vivants.

Enfin, si vous faites partie des millions de personnes qui souffrent d'allergie, notez que vous pouvez faire de nombreuses choses sans aller remplir les poches de l'industrie pharmaceutique.

Mangez de la nourriture saine, naturelle, peu transformée (légumes et fruits frais), peu cuite, et même crue quand c'est possible, dont des aliments fermentés, optimisez votre taux de vitamine D. Corrigez votre ratio oméga-3/oméga-6 (qui doit être idéalement entre 1/1 et 1/5, non 1/20 ou 1/30 comme c'est en général le cas dans le régime moderne) et vous donnerez à votre système immunitaire les bons fondements pour se réguler naturellement.

Pour un soulagement immédiat de vos symptômes allergiques, irriguez vos sinus avec un spray d'eau de mer, essayez l'acupuncture et servez-vous de la plante suprême contre les allergies, le plantain qui est à la fois émollient, adoucissant, anti-inflammatoire, expectorant, antispasmodique bronchique et immunostimulant :

- Contre les rhinites asthmatiques et l'asthme : prendre 3 gélules d'extrait sec par jour.

- En cas de conjonctivite, appliquer sur les yeux clos une compresse imbibée d'une infusion à 4 % de feuilles de plantain (40 grammes de feuilles pour 1 litre d'eau).

Il existe également de très nombreuses solutions en gemmothérapie (bourgeons), aromathérapie (huiles essentielles) et oligothérapie (éléments-trace) qui sont détaillées dans le dernier numéro de Plantes & Bien-Être, dans un dossier passionnant réalisé par Danielle Roux, qui est docteur en pharmacie et l’une des meilleures spécialistes européennes de phytothérapie (médecine par les plantes).

Pour un traitement de fond de vos allergies, envisagez une désensibilisation chez un allergologue. Enfin, si vous avez des enfants, envisagez très sérieusement avec votre pédiatre de leur donner régulièrement de la cacahuète sous forme de beurre de cacahuète. La même approche avec les autres allergènes pourrait fonctionner également pour empêcher l'apparition future d'allergies.

- Source : Dr. Mercola-Traduction Jean-Marc Dupuis

00:05 Publié dans Cuisine / Gastronomie, Ecologie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : cuisine, alimentation, santé, médecine |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

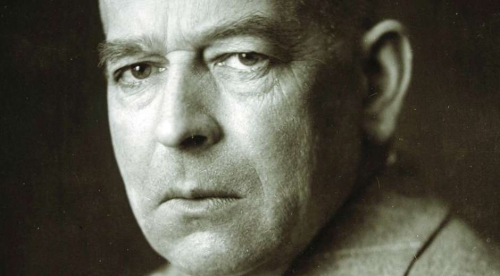

Carl Schmitt (1888-1985): Brief Biography of the Controversial German Jurist

Carl Schmitt (1888-1985): Brief Biography of the Controversial German Jurist

by Colm Gillis

Ex: http://carlschmittblog.com

Carl Schmitt was one of the greatest intellectuals of the 20th century. This is a very brief overview of his remarkable life and career.

Carl Schmitt was born in 1888. Plettenberg, his home town, was a Protestant hamlet, but Schmitt was baptized a Catholic. As was typical for those of Rhenish Catholic stock, Schmitt was possessed of a strong sense of identity. This was combined with an equally strong sense of transnationalism. Circumstances, the Rhenish Catholic outlook, and prevalent sectarianism in Germany at the time, meant that he was exposed to pluralism, religious divisions, political questions, and geopolitics.1

He received first and second-level education in Catholic institutions, acquiring a thorough understanding of the humanities, in particular religion and Greek. At the same time, Schmitt was exposed to materialism. Familiarity with ideologies like Liberalism bred contempt and Schmitt maintained his religious zeal long after he left behind his formative years.2

After attending Universities in Berlin and then Strassburg, Schmitt received his doctorate in 1910. Following graduation, he honed his legal skills. At Strassburg, Schmitt took a stance against positivistic legal theory. Positivism located legitimacy in the sheer fact of a sovereign government. Analysis of legal rulings was restricted to the intention of the lawgiver. Positivism ruled out the use of, for example, natural law theories, and Schmitt’s Catholic upbringing most likely was what made him averse to such a legal approach.3

At this stage Schmitt’s views on law were informed by the neo-Kantians, who placed a ‘right’ above the state and who saw it as the function of the State to fulfil this right. While professing loyalty to the State and to a perceived right order, Schmitt tended to subordinate the individual, an anti-liberal stance maintained throughout his career.4

Schmitt’s meeting with the barrister and deputy of the Center party, Dr Hugo am Zehnhoff, in 1913 influenced Schmitt profoundly. In particular Schmitt turned away from subjugating law to a set of transcendent norms. Instead concrete circumstances were to provide the basis for law from now on.5

Dr Hugo am Zehnhoff

Before the war, he published two books. But his inclinations at this stage were not overly political. This apoliticism was common amongst German intellectuals at the time. Generally, the existing order was accepted as is. It was felt inappropriate for academics to weigh in on practical issues.6

After passing his second law exam in 1915, Schmitt volunteered for the infantry, but suffered a serious back injury. So he served out WWI performing civil duties in Bavaria which were essential to the war effort. Schmitt administered the martial law that existed throughout Bavaria and elsewhere in Germany. He married his first wife, Pawla Dorotić, a Serb whom he later divorced in 1924, at this time. Pawla’s surname was added to his so as to give himself an aristocratic air, an indication of Schmitt’s determination to advance himself.7

Hindenburg and Ludendorff formed an effective dictatorship in Germany during WWII

In line with much of Conservative German thought at the time, Schmitt viewed the state – not as a repressive or retrograde force that stifled freedom – but as a bastion of tradition securing order. Dictatorship was mused upon. This, in Schmitt’s mind, was constrained by a legal order and could only act within that legal order. Dictatorship was functional, temporary, and provided a measure of order in emergency situations, but was not to be transformative and break from the structure which preceded it and dictated to it. In other words, it was to be a dictatorship in the mould of classical dictatorship which was extant in the Roman republic.8

As for the purpose of the world war itself, Schmitt displayed his ever-present aloofness. While many thinkers in Germany saw the war in very stark terms, as a struggle to uphold the ‘spirit’ or as a struggle against Enlightenment rationalism, Schmitt opined that the war proved the tragic existence of man in the modern world. Men had lost their souls and corrupted by a glut of knowledge and a dearth of spirituality.9

Strassburg’s loss to the Reich after the war meant that Schmitt had to downgrade to a lectureship at the School of Business Administration in Munich, a post which he achieved with the aid of Moritz Julius Bonn. Bonn would remain a close friend. Despite their political differences, Schmitt and Moritz were companions until the end of Weimar.10

While Schmitt would be forever known as a provocative critic of the Weimar republic, he was always loyal to its institutions from its inception, albeit with reservations. Catholics had their hand strengthened by the Weimar republic. Hence, Schmitt and others were unlikely to overthrow an institution that had favoured them. On the other hand, Versailles was perceived as a humiliation and seemingly even worse for Schmitt, a distortion of law. Antipathies were harboured by Schmitt towards the US on these grounds. America was considered it to be a hypocritical entity who impressed upon people a neutral, liberal international law operating alongside an open economic system, but because the latter had to be guaranteed, the former could not be neutral.11

Differences between jurists that existed before the onset of war were further exacerbated after the war. Hans Kelsen, the normativist scholar, was Schmitt’s main rival. Those like Schmitt opposed what they saw as an unrealistic objectivism.12

After the war, Schmitt turned his back on neo-Kantian perceptions of right. Instead he interpreted the turmoil of the war and post-war anarchy as proof for his ‘decisionist’ theories. Law and legitimate rule were located in the hands of a clearly defined sovereign. Legal procedure would be kept to a minimum. Justice would be substantive as opposed to merely formal.

Schmitt placed order before the application of law and he increasingly saw many of the assumptions and modus operandi of Liberalism, democracy, and parliamentarianism to be unworkable, subversive, irrational, prone to elitism, and too politically agnostic in the Germany of his day. His criticisms of domestic law mirrored those of international law – too much faith was placed in supposedly neutral theories of law. Sheer ignorance of power structures or realities on the ground was what kept ‘rule-of-law’ theories going.13

Schmitt mused much on dictatorships like the one headed by Sulla, the Roman dictator

Disillusioned with modern politics, he sought refuge in counter-revolution thinkers, notably de Maistre, Bonald, and Donoso Cortés. Schmitt did much to resurrect the reputation of Cortés in particular, an ex-liberal from Spain who produced far-reaching analyses of mid-19th century European politics. Cortés’ discourse was framed in highly theological language.14

Schmitt distanced himself from ‘conservative revolutionaries,’ however. Conservative revolutionaries held that traditional conservatism needed to utilize modern techniques to save Germany from atheism, Liberalism and Bolshevism. Schmitt considered their opinions too crude. Diversification was key and Schmitt interacted with the left and right and every shade in between, with the possible exception of Liberals, although he never seems to have found an intellectual soul-mate.15

Yet Schmitt concurred with the conservative revolutionaries in one important respect; namely that he found the age to be dead, lacking in vitality, and overly rationalistic. Liberalism and parliamentarianism were increasingly in the cross-hairs and the first pre-emptive strike was his book Political Romanticism (1919), which was released after the war. This was not a template for later Schmittian works, but was symptomatic of an impatience with relentless individualism. One can read many subtexts from this work that would appear in his more celebrated studies.16

Following Political Romanticism, Schmitt’s targets were pinpointed to greater precision. Dictatorship (1921), Political Theology (1922), and The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy (1923), were three noteworthy books released in the early 1920s. Liberalism’s flawed ontology of mankind was critiqued. Contradictions in Liberalism were exposed. Dangerous phantasms of parliamentarianism were rationally elucidated. Power in the ‘real’ world of politics was discussed. And more. 17

At the same time, Schmitt was aware of the increasing totalitarianism evident in modern politics, being one of the first to recognize this trend, and even articulating an awareness of the power of modern media. His position was somewhere in between the value-neutral position of Liberalism and the absolute control espoused by Statists. He was acutely aware of the weaknesses of Weimar Germany in the face of ideologies demanding increasing loyalty from their members. In parallel with his fear of totalitarianism was his disgust at the way that private interests were embedding themselves into public institutions. Nevertheless, by 1925, the constitutional lawyer Richard Thoma was accusing Schmitt of authoritarianism, a penchant for the irrational and desiring the hegemony of the Church in Germany.18

Schmitt gained a reputation as a legal theorist who leant strongly on article 48 of the Weimar Constitution during this period. In this article, a provision was made for emergency rule in the event of political breakdown. For Schmitt, as opposed to those like Thoma, law was meaningless without a stable order in place. He took a very realistic perspective, and in fact was not ideologically inclined against democracy or parliament. But he harboured misgivings that the supposed nature of democracy or parliamentarianism, as articulated by his contemporaries, was historically accurate. In any event, the modern forces which Liberalism had unleashed would put paid to whatever the interest-based new order tried to accomplish, Schmitt also surmised.19

Frontispiece of a booklet of the Weimar Constitution

Schmitt spent the bulk of the 1920s at Bonn, and moved there in 1922 after stints at Berlin and Greifswald, leaving Bonn in 1928. In 1926 he got married to Duschka Todorovitsch, another Slav. In the next several years, two of his most important books, The Concept of the Political (1927, with a new and highly amended edition appearing in 1932) and Constitutional Theory (1928) were published. The former, in particular, marked a ‘turn’ in Schmitt’s thought: he was now less inclined towards the Catholic Church. Already he had been turning to Rosseau and his theories of the identity of people and government.20

Schmitt and his wife in the 1920s

Introducing Schmitt’s famous ‘friend-enemy thesis,’ The Concept of the Political was a revolutionary book in political science and philosophy. Continuing in the same vein as earlier works such as Political Theology, Schmitt saw the State as the only body competent to pursue political existence by identifying the friend-enemy distinction. Despite the apparent amorality of the study, many commentators, including his Catholic friend Waldemar Gurion, were impressed by what was undeniably an astute analysis.21

Both the Weimar Republic and Schmitt the intellectual reached the height of their powers in the years immediately before the Wall Street crash. Schmitt would go to Berlin just before the fatal blows were struck against the nascent republic. He now commanded widely-held kudos as a jurist, and the financial crisis would now give him influence as a political adviser.22

Germany was on the precipice at this stage and article 76 of the Weimar constitution particularly disturbed Schmitt. He harboured no illusions about what this provision, which enabled a popularly elected party to do as it pleased with the constitution, signified for those antagonistic towards the State. Schmitt now became close to Johannes Popitz, Franz von Papen, and General Kurt von Schleicher, all of whom represented traditional German values. During the chancellorship of Heinrich Brüning, the Centre party leader, he acted as constitutional advisor to President Paul von Hindenburg. True to his past form, Schmitt provided legal cover for the use of emergency decrees which helped see the republic through the treacherous currents of the early 1930s. Surrounded by practical men, Schmitt and his colleagues were only interested in making Germany a strong and stable country. At this time, he also recognized the need for government to concern itself with economic matters. Schmitt neither sought to repress trade unions nor exalt business interests within the corridors of powers, but advocated the pursuance of an economic policy that was neutral.23

There was more than a touch of Keystone Cops about Schmitt, von Papen, von Schleicher, and other traditional conservatives, as they struggled to manoeuvre and deal with the burgeoning National Socialist movement. One of Schmitt’s treatises, Legality and Legitimacy, was used by supporters of von Papen and von Schleicher to justify the increasingly authoritarian measures required to cope with the turmoil in Germany, which by 1932 had become pervasive. Ill-judged use of Schmitt’s theory handed an initiative to the NSDAP in 1932 during a landmark case in Prussia. In 1932, he also wrote an article in the run-up to elections called The Abuse of Legality, where he repeated his arguments in Legality and Legitimacy. The most important of his arguments, in this context, was the conviction that the Constitution cannot be used as a weapon against itself.24

In 1932, von Schleicher tried to outwit the NSDAP. He lifted bans on paramilitary groups aligned with the National Socialist movement, but also tried to woo right-wing voters through innovative economic measures. Strategic support was lent to these tactics by Schmitt. However, these plans backfired. The NSDAP grew in strength and Hitler was underestimated by those like the conservatives, who believed in their own superiority and powers of manipulation. Meanwhile, Schmitt’s ideas were commoditized by those like Hans Zehrer and Horst Grüneberg, editors of Die Tat, who found knives in Schmitt’s writings where there were only scalpels.25

Schmitt’s article ‘The Fuehrer protects the right’

One last episode of farce remained before the death of Weimar: Von Schleicher conversed with Hindenburg about banning anti-constitutional parties that were now incapable of being contained in 1933. This conversation was leaked. Schmitt’s name was associated with the backroom shenanigans, and he had an embittered, and personal exchange with Prelate Kaas, leader of the Centre Party, who charged Schmitt with promoting illegality. Schmitt later heard about Hitler’s appointment in a café. Just at this time, he was moving from Berlin to Cologne, a move unrelated to the political trouble. Schmitt’s departure from the capital seemed just as well timed as his arrival.26

True to his form of being able to condense the most momentous of events into a single phrase, Schmitt remarked on January 30 1933 that ‘one can say that Hegel died.’27 Schmitt saw Hitler’s rise to power through the lens of vitality and Kultur. National Socialism had ousted a bureaucracy that had powered the rise of the German state, only to disappear once the work of the bureaucratic State was complete. He joined the NSDAP in May 1933, although it was not a significant gesture, because the purging of the civil service had meant that Schmitt was virtually compelled to join.28

A full professorship in Berlin, a post at the Prussian state council, a nomination to the nascent Akademie für Deutsches Recht, an appointment to the editorial board of the publication of National Socialist legal theorists Das Deutsche Recht, and appointment to the head of higher education instructors of the National-Socialist Federation of German jurists came in quick succession in 1933.29

In 1934 he partly backed that year’s notorious purges in the provocatively titled The Führer Protects the Law. In his opposition to the slaughter of innocents, Schmitt showed his astuteness. He was able to cite both Hitler and Goering, who admitted publicly that mistakes were made in the purges. Schmitt called for a state of normality to be re-imposed, now that the danger to the state had passed. Despite his attempts to quell the bloodshed in Germany, Schmitt’s writings appeared to emigrés as rubberstamping a fanatical government that was out-of-control. His old friend Gurian coined the term ‘Crown Jurist of the Third Reich’ for Schmitt.30

Protestations of emigrés against Schmitt didn’t go unnoticed by the authorities, and their dredging up of Schmitt’s past stance towards the NSDAP stifled, and then reversed, Schmitt’s rise through the ranks. It seemed as if the more Schmitt tried to ingratiate himself – by 1936 he had approved of the Nuremberg laws and also proposed a purging of the law-books of Jewish influence – the more he alienated himself.31

The SS and their publication, Das Schwarze Korps, were the vanguard of ideological purity in the Third Reich. From this platform, they were eventually able to force Schmitt to leave the public bodies he had served in and he retired to academia. Disillusioned, he drew more on the theories of Thomas Hobbes, in particular his theory of obedience being given in return for protection in a 1938 work. Schmitt also explored international law, and would remain a critic of the global order until his death, notably calling for an international system where countries would guard Grossraum, large swathes of territory that powerful States would claim as their backyard as the US had done with the Monroe Doctrine. This should not be confused with racially charged Lebensraum theories.32

In the last phase of the war, Schmitt served in the German equivalent of the Home Guard and was captured by the Soviets. Ironically, the Bolsheviks released him after considering him to be of no value, either because of what he told the Russians or because of his age. Schmitt did not receive the same leniency from the Americans and he spend thirteen months, after his arrest in September 1945, incarcerated, also suffering the ignominy of having his massive library confiscated. The main accusation levelled against him was that he had provided intellectual cover for the NSDAP Lebensraum policy.33 Chastened by his experiences, Schmitt retreated into what he told his interrogator Robert Kempner was a ‘security of silence’34 and he composed the following lines which served to summate the attitude he adopted after the war

Look at the author most precisely

Who speaks of silence oh so nicely;

For while he’s speaking of quiescence

He outwits his own obsolescence.35

Schmitt did not maintain a strict silence, as the lines suggest, but continued his manner of couching his writings in esotericism, a manner which he adopted during NSDAP rule. After his ordeal at the hands of the Americans, Schmitt retired to a house which was named San Casciano, either after the name of the residence that Machiavelli retired to after he was ousted from power, or after the name of a Christian martyr in the reign of Diocletian who was stabbed to death with a stylo by one of his students.36

Even in his old age, Schmitt divided opinion, but kept producing works of literary quality. The Nomos of the Earth (1950) was Schmitt’s last major work and his key study on international relations. That is not to downgrade the quality of many of his later works, such as Theory of the Partisan (1963), which are still highly relevant in the modern world. He also revised many of his earlier writings so as to keep pace with the new world that had replaced the previous European order that had existed from the 17th century. Theology came back into focus for Schmitt and his Political Theology II (1970) critiqued the classical position adopted by Erik Peterson, in respect of the Church’s position towards politics. Friendships with Jacob Taubes, a Jewish rabbi, and Alexandre Kojève, the outstanding Hegelian philosopher, revived his reputation.37

Schmitt’s downfall somewhat mirrored similar events surrounding Machiavelli. His death in his home town of Plettenberg at the grand age of 97 matched the somewhat similar life-span enjoyed by Hobbes.38 Life for both may have been nasty and brutish, at times, but was definitely not short!

Currently, I am researching a book on Carl Schmitt because I need to know about politics. Any comments or suggested corrections to this post are welcome. I have already authored one book Mysteries of State in the Renaissance. My Amazon page is here.

NOTES

[1] Carl Schmitt’s International Thought: Order and Orientation William Hooker Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2009 pp. xiii; State, Movement, People: The Triadic Structure of Political Unity Carl Schmitt (Simona Draghici (Trans.)) Plutarch Press Corvalis, Or. 2001 pp. ix; The Concept of the Political (Expanded Edition) Carl Schmitt (George Schwab (Trans.)) The University of Chicago Press Chicago 2007 pp. 4; Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 3-5.

[2]The Concept of the Political (Expanded Edition) Carl Schmitt (George Schwab (Trans.)) The University of Chicago Press Chicago 2007 pp. 4; The Challenge of the Exception: Introduction to the Political Ideas of Carl Schmitt Between 1921 and 1936 (2nd Ed.) George Schwab Greenwood Press New York Westport, Conn. London 1989 pp. 13; Ibid. pp. 6-7; Dictatorship Carl Schmitt (Michael Hoelzl and Graham Ward (Trans.)) Polity Press Malden, MA Cambridge 2014 pp. xvii.

[3] The Concept of the Political (Expanded Edition) Carl Schmitt (George Schwab (Trans.)) The University of Chicago Press Chicago 2007 pp. 4; Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 9, 13.

[4] The Challenge of the Exception: Introduction to the Political Ideas of Carl Schmitt Between 1921 and 1936 (2nd Ed.) George Schwab Greenwood Press New York Westport, Conn. London 1989 pp. 14; Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 10-11.

[5] The Challenge of the Exception: Introduction to the Political Ideas of Carl Schmitt Between 1921 and 1936 (2nd Ed.) George Schwab Greenwood Press New York Westport, Conn. London 1989 pp. 13.

[6] Ibid. pp. 14; Carl Schmitt’s International Thought: Order and Orientation William Hooker Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2009 pp. xiii; Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 13-15.

[7] Dictatorship Carl Schmitt (Michael Hoelzl and Graham Ward (Trans.)) Polity Press Malden, MA Cambridge 2014 pp. x-xi; The Concept of the Political (Expanded Edition) Carl Schmitt (George Schwab (Trans.)) The University of Chicago Press Chicago 2007 pp. 4; Carl Schmitt’s International Thought: Order and Orientation William Hooker Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2009 pp. xiii.

[8] Dictatorship Carl Schmitt (Michael Hoelzl and Graham Ward (Trans.)) Polity Press Malden, MA Cambridge 2014 pp. xi-xii; The Challenge of the Exception: Introduction to the Political Ideas of Carl Schmitt Between 1921 and 1936 (2nd Ed.) George Schwab Greenwood Press New York Westport, Conn. London 1989 pp. 14-15; Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 18-20.

[9] Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 16-18.

[10] Ibid. pp. 22-23.

[11] The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy Carl Schmitt (Ellen Kennedy (Trans.)) MIT Press Cambridge, Mass. London 2000 pp. xxvii-xxviii; Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 28, 53-54; The Geopolitics Of Separation: Response to Teschke’s ‘Decisions and Indecisions’ Gopal Balakrishnan New Left Review Vol. 68 Mar-Apr 2011 pp. 59; The Nomos of the Earth in the International Law of the Jus Publicum Europaeum Carl Schmitt (G.L. Ulmen (Trans.)) Telos Press New York 2003 pp. 12-19.

[12] State, Movement, People: The Triadic Structure of Political Unity Carl Schmitt (Simona Draghici (Trans.)) Plutarch Press Corvalis, Or. 2001 pp. ix-x; Constitutional Theory Carl Schmitt (Jeffrey Seitzer (Trans.)) Duke University Press Durham London 2008 pp. 3; Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 36.

[13] Carl Schmitt’s quest for the political: Theology, decisionism, and the concept of the enemy Maurice A. Auerbach Journal of Political Philosophy Winter 1993-94 Vol. 21 No. 2 pp. 201; Carl Schmitt’s Critique of Liberalism: Against Politics as Technology John P. McCormick Cambridge University Press Cambridge 1997 pp. 2; State, Movement, People: The Triadic Structure of Political Unity Carl Schmitt (Simona Draghici (Trans.)) Plutarch Press Corvalis, Or. 2001 pp. x-xi; The Concept of the Political (Expanded Edition) Carl Schmitt (George Schwab (Trans.)) The University of Chicago Press Chicago 2007 pp. 7, pp. 13; Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 37.

[14] Carl Schmitt’s quest for the political: Theology, decisionism, and the concept of the enemy Maurice A. Auerbach Journal of Political Philosophy Winter 1993-94 Vol. 21 No. 2 pp. 203; Carl Schmitt and Donoso Cortés Gary Ulmen Telos 2002 No. 125 pp. 69-79; The Challenge of the Exception: Introduction to the Political Ideas of Carl Schmitt Between 1921 and 1936 (2nd Ed.) George Schwab Greenwood Press New York Westport, Conn. London 1989 pp. 22-23.

[15] Carl Schmitt: The Conservative Revolutionary Habitus and the Aesthetics of Horror Richard Wolin Political Theory 1992 Vol. 20 No. 3 pp. 428-429; Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 56-62, 135-139. He made his disassociation from conservative revolutionaries quite forceful at times, for instance complaining when his name nearly appeared in the same collection of essays as the Austrian corporatist thinker Prof. Othmar Spann. Schmitt also associated with leftist thinkers like Benjamin and Kirchheimer, both who were indebted to him. Schmitt did attract right wing students who were pessimistic about the German state, but these were only interested in those parts of his lectures construed as anti-Weimar and the subtlety of Schmitt’s thought was ignored.

[16] Carl Schmitt’s quest for the political: Theology, decisionism, and the concept of the enemy Maurice A. Auerbach Journal of Political Philosophy Winter 1993-94 Vol. 21 No. 2 pp. 206; Political Romanticism Carl Schmitt (Guy Oakes (Trans.)) MIT Press Cambridge, Mass. London 1986.

[17] The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy Carl Schmitt (Ellen Kennedy (Trans.)) MIT Press Cambridge, Mass. London 2000 pp. xvi.

[18] Ibid. pp. xiv, xli; Carl Schmitt’s quest for the political: Theology, decisionism, and the concept of the enemy Maurice A. Auerbach Journal of Political Philosophy Winter 1993-94 Vol. 21 No. 2 pp. 207; State, Movement, People: The Triadic Structure of Political Unity Carl Schmitt (Simona Draghici (Trans.)) Plutarch Press Corvalis, Or. 2001 pp. viii.

[19] The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy Carl Schmitt (Ellen Kennedy (Trans.)) MIT Press Cambridge, Mass. London 2000 pp. xxvii-xxx; Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 72-73; Four Articles: 1931-1938 Carl Schmitt (Simona Draghici (Trans.)) Plutarch Press Corvalis, Or. 1999 pp. x-xi; In his introduction to one of Schmitt’s books, Christopher Dawson writes; To the traditionalist this alliance of liberal humanitarianism with the forces of destruction appears so insane that he is tempted to see in it the influence of political corruption or the sinister action of some hidden hand. It must, however, be recognised that it is no new phenomenon; in fact, it has formed part of the liberal tradition from the beginning. The movement which created the ideals of liberal humanitarianism was also the starting point of the modern revolutionary propaganda which is equally directed against social order and traditional morality and the Christian faith. In The Necessity of Politics: An Essay on the Representative Idea of the Church and Modern Europe Carl Schmitt (E.M. Codd (Trans.)) Sheed & Ward London 1931 pp. 15-16.

[20] State, Movement, People: The Triadic Structure of Political Unity Carl Schmitt (Simona Draghici (Trans.)) Plutarch Press Corvalis, Or. 2001 pp. xi; Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 44; The Concept of the Political (Expanded Edition) Carl Schmitt (George Schwab (Trans.)) The University of Chicago Press Chicago 2007; Constitutional Theory Carl Schmitt (Jeffrey Seitzer (Trans.)) Duke University Press Durham London 2008; The Challenge of the Exception: Introduction to the Political Ideas of Carl Schmitt Between 1921 and 1936 (2nd Ed.) George Schwab Greenwood Press New York Westport, Conn. London 1989 pp. 25-26.

[21] Carl Schmitt’s International Thought: Order and Orientation William Hooker Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2009 pp. 1-5; The Concept of the Political (Expanded Edition) Carl Schmitt (George Schwab (Trans.)) The University of Chicago Press Chicago 2007; Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 93-94.

[22] Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 85; State, Movement, People: The Triadic Structure of Political Unity Carl Schmitt (Simona Draghici (Trans.)) Plutarch Press Corvalis, Or. 2001 pp. xi.

[23] The Definite and the Dubious: Carl Schmitt’s Influence on Conservative Political and Legal Theory in the US Joseph W. Bendersky Telos 2002 No. 122 pp. 36, 43; Movement, People: The Triadic Structure of Political Unity Carl Schmitt (Simona Draghici (Trans.)) Plutarch Press Corvalis, Or. 2001 pp. viii-xii. It’s significant that Heinrich Muth noted that someone who strove in the manner of Schmitt could not logically have been in league with groups like the NSDAP; The Concept of the Political (Expanded Edition) Carl Schmitt (George Schwab (Trans.)) The University of Chicago Press Chicago 2007 pp. 14; Political Romanticism Carl Schmitt (Guy Oakes (Trans.)) MIT Press Cambridge, Mass. London 1986 pp. ix-x; Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 114-116, 121-122.

[24] Legality and Legitimacy Carl Schmitt (Jeffrey Seitzer (Trans.)) Duke University Press Durham London 2004 pp. xvi, xx-xxi; State, Movement, People: The Triadic Structure of Political Unity Carl Schmitt (Simona Draghici (Trans.)) Plutarch Press Corvalis, Or. 2001 pp. xi; Constitutional Theory Carl Schmitt (Jeffrey Seitzer (Trans.)) Duke University Press Durham London 2008 pp. 20-23; Political Romanticism Carl Schmitt (Guy Oakes (Trans.)) MIT Press Cambridge, Mass. London 1986 pp. x-xi.

[25] Legality and Legitimacy Carl Schmitt (Jeffrey Seitzer (Trans.)) Duke University Press Durham London 2004 pp. xxi; Constitutional Theory Carl Schmitt (Jeffrey Seitzer (Trans.)) Duke University Press Durham London 2008 pp. 22; Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 152-153; The Challenge of the Exception: Introduction to the Political Ideas of Carl Schmitt Between 1921 and 1936 (2nd Ed.) George Schwab Greenwood Press New York Westport, Conn. London 1989 pp. vi.

[26] Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 184-189.

[27] Carl Schmitt: The Conservative Revolutionary Habitus and the Aesthetics of Horror Richard Wolin Political Theory 1992 Vol. 20 No. 3 pp. 424.

[28] Ibid. pp. 425; State, Movement, People: The Triadic Structure of Political Unity Carl Schmitt (Simona Draghici (Trans.)) Plutarch Press Corvalis, Or. 2001 pp. xiii.

[29] State, Movement, People: The Triadic Structure of Political Unity Carl Schmitt (Simona Draghici (Trans.)) Plutarch Press Corvalis, Or. 2001 pp. xii.

[30] Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 215-216, 23-224; The Leviathan in the State Theory of Thomas Hobbes: Meaning and Failure of a Political Symbol Carl Schmitt (George Schwab and Erna Hilfstein (Trans.)) Greenwood Press Westport, Conn. London 1996 pp. xvi.

[31] Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 224-228; For an excellent summary of Schmitt’s true attitudes towards the Jews see New Evidence, Old Contradictions: Carl Schmitt and the Jewish Question Joseph Bendersky Telos 2005 No. 132 pp. 64-82.

[32] The Leviathan in the State Theory of Thomas Hobbes: Meaning and Failure of a Political Symbol Carl Schmitt (George Schwab and Erna Hilfstein (Trans.)) Greenwood Press Westport, Conn. London 1996 pp. xii-xiii; Carl Schmitt, theorist for the Reich Joseph W. Bendersky Princeton University Press Princeton, N.J. Guildford 1983 pp. 224-228; The Geopolitics Of Separation: Response to Teschke’s ‘Decisions and Indecisions’ Gopal Balakrishnan New Left Review Vol. 68 Mar-Apr 2011 pp. 68.

[33] Carl Schmitt’s International Thought: Order and Orientation William Hooker Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2009 pp. xiii; Political Theology II: The Myth of the Closure of Any Political Theory Carl Schmitt (Michael Hoelzl and Graham Ward (Trans.)) Polity Press Cambridge 1970 pp. 1.

[34] Political Theology II: The Myth of the Closure of Any Political Theory Carl Schmitt (Michael Hoelzl and Graham Ward (Trans.)) Polity Press Cambridge 1970 pp. 1.

[35] Ibid. pp. 1.

[36] Ibid. pp. 2.

[37] Ibid.; Constitutional Theory Carl Schmitt (Jeffrey Seitzer (Trans.)) Duke University Press Durham London 2008 pp. 2; Carl Schmitt’s International Thought: Order and Orientation William Hooker Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2009 pp. 2; The Nomos of the Earth in the International Law of the Jus Publicum Europaeum Carl Schmitt (G.L. Ulmen (Trans.)) Telos Press New York 2003; The Theory of the Partisan: Intermediate Commentary on the Concept of the Political Carl Schmitt (A.C. Goodson (Trans.)) Michigan State University Lansing 2004; Letters of Jacob Taubes & Carl Schmitt Timothy Edwards (Trans.) Accessed from http://www.scribd.com on 25/10/14; Alexandre Kojève-Carl Schmitt Correspondence and Alexandre Kojève, “Colonialism from a European Perpective (Erik de Vries (Trans.)) Interpretation 2001 Vol. 29 No. 1 pp. 91-130.

[38] Carl Schmitt’s International Thought: Order and Orientation William Hooker Cambridge University Press Cambridge 2009 pp. xiii; Hobbes lived until the age of 91, an even more remarkable feat than Schmitt’s longevity!

00:05 Publié dans Biographie, Révolution conservatrice, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : carcatholicisme, révolution, conservatrice, république de weimar, weimar, années 20, années 30, l schmitt, allemagne, droit, constitution, théorie politique, philosophie, philosophie politique, politologie, sciences politiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Le clash des civilisations au prisme de la musique classique

À ma grande honte, je ne connaissais pas Fazıl Say. Dimanche 19 avril, j’ai assisté à un concert de lui, avec l’Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, dans le cadre du festival Heidelberger Frühling.

Turc d’Ankara, Fazıl Say est un pianiste renommé et un compositeur de talent qui puise son inspiration dans les rythmes populaires, comme Bartók, Enesco ou Kodály. Il a attiré l’attention sur lui en 2013 quand il eut maille à partir avec les autorités de son pays, en raison de plusieurs tweets où il affirmait son athéisme, se moquait du muezzin trop pressé et citait deux vers d’Omar Khayyām :

Vous dites qu’il y coule des rivières de vin, le paradis est-il une taverne ?

Vous dites qu’à chaque croyant sera donné deux houris, le paradis est-il un bordel ?

Ces mots sacrilèges ont valu à Fazıl Say d’être condamné pour blasphème à 10 mois de prison avec sursis. Ne riez pas, amis lecteurs, l’islam convient aux esprits simples, comme à cette malheureuse Inès de Roubaix, l’épouse de Kevin, qui apprend l’arabe à ses enfants car c’est la langue qu’ils auront à parler au paradis, et les mêmes sornettes – houris et rivières de lait et de miel – sont promises à ceux qui se font exploser la tronche dans des attentats-suicides.

Rappelons que Khayyām, redécouvert par Fitzgerald au XIXe siècle, est avec Hafez, dont Goethe s’inspira dans son recueil Le Divan, et Saadi l’un des trois grands poètes de la Perse islamique. Khayyām, bon vivant fort mécréant, amateur de femmes et de vin, eut à pâtir de la vindicte des bigots. Persécuté et sans postérité, comme la plupart des artistes et des érudits non théologiens sous le joug islamique, il ne doit d’être connu qu’à l’intérêt que les Occidentaux lui ont porté.

Comme rien n’est simple, la Turquie de Fazıl Say n’en abrite pas moins l’une des confréries soufies les plus réputées de l’islam, celle des derviches tourneurs, sommet de la spiritualité musulmane, l’équivalent des ordres mendiants chez nous, quand la religion se libère de toutes attaches prosaïques, et Istanbul est riche des plus beaux monuments de l’art islamique.

Preuve, s’il en est, à l’encontre des butors qui vous agonisent de noms d’oiseau quand vous faites mine de dire un mot gentil sur l’islam, que la civilisation musulmane a aussi produit de beaux fruits, certes sur les décombres des civilisations précédentes, comme pour les vampiriser, et qu’elle ne crée plus rien depuis quatre siècles et le glorieux règne de Soliman le Magnifique ou celui de Shah Abbas Ier en Iran, le bâtisseur de l’Ispahan moderne.

La Turquie d’aujourd’hui est dans l’entre-deux de l’Orient et de l’Occident. Istanbul connaît une intense vie musicale, et plusieurs orchestres philharmoniques y ont acquis une renommée internationale. Les succès d’un Fazıl Say en attestent.

Peut-être la musique symphonique, avec l’opéra, est-elle le signe le plus évident de l’unification du monde sur le modèle occidental. Elle a gagné les Amériques, puis l’Asie. A contrario des pays qui n’ont pas, ou plus, d’orchestres philharmoniques, au Moyen-Orient et en Afrique, qui dessinent une carte d’un clash des civilisations, ou des cultures, n’en déplaise à l’ami Gauthier, autrement que dans la conception martiale et militariste des néo-conservateurs états-uniens.

Il faut davantage de Fazıl Say dans le monde musulman car la musique symphonique adoucit les mœurs des frustes et des barbares.

00:05 Publié dans Musique, Musique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : musique, piano, fazil say |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

History and Decadence: Spengler's Cultural Pessimism Today

Dr. Tomislav Sunic expertly examines the Weltanschauung of Oswald Spengler and its importance for today's times.

by Tomislav Sunic

Ex: http://traditionalbritain.org

Oswald Spengler (1880-1936) exerted considerable influence on European conservatism before the Second World War. Although his popularity waned somewhat after the war, his analyses, in the light of the disturbing conditions in the modern polity, again seem to be gaining in popularity. Recent literature dealing with gloomy postmodernist themes suggests that Spengler's prophecies of decadence may now be finding supporters on both sides of the political spectrum. The alienating nature of modern technology and the social and moral decay of large cities today lends new credence to Spengler's vision of the impending collapse of the West. In America and Europe an increasing number of authors perceive in the liberal permissive state a harbinger of 'soft' totalitarianism that my lead decisively to social entropy and conclude in the advent of 'hard' totalitarianism'.

Spengler wrote his major work The Decline of the West (Der Untergang des Abendlandes) against the background of the anticipated German victory in World War I. When the war ended disastrously for the Germans, his predictions that Germany, together with the rest of Europe, was bent for irreversible decline gained a renewed sense of urgency for scores of cultural pessimists. World War I must have deeply shaken the quasi-religious optimism of those who had earlier prophesied that technological intentions and international economic linkages would pave the way for peace and prosperity. Moreover, the war proved that technological inventions could turn out to be a perfect tool for man's alienation and, eventually, his physical annihilation. Inadvertently, while attempting to interpret the cycles of world history, Spengler probably best succeeded in spreading the spirits of cultural despair to his own as well as future generations.

Like Giambattista Vico, who two centuries earlier developed his thesis about the rise and decline of culture, Spengler tried to project a pattern of cultural growth and cultural decay in a certain scientific form: 'the morphology of history'--as he himself and others dub his work--although the term 'biology' seems more appropriate considering Spengler's inclination to view cultures and living organic entities, alternately afflicted with disease and plague or showing signs of vigorous life. Undoubtedly, the organic conception of history was, to a great extent, inspired by the popularity of scientific and pseudoscientific literature, which, in the early twentieth century began to focus attention on racial and genetic paradigms in order to explain the patterns of social decay. Spengler, however, prudently avoids racial determinism in his description of decadence, although his exaltation of historical determinism in his description often brings him close to Marx--albeit in a reversed and hopelessly pessimistic direction. In contrast to many egalitarian thinkers, Spengler's elitism and organicism conceived of human species as of different and opposing peoples, each experiencing its own growth and death, and each struggling for survival. 'Mankind', writes Spengler, should be viewed as either a 'zoological concept or an empty word'. If ever this phantom of mankind vanishes from the circulation of historical forms, 'we shall ten notice an astounding affluence of genuine forms.. Apparently, by form, (Gestalt), Spengler means the resurrection of the classical notion of the nation-state, which, in the early twentieth century, came under fire from the advocates of the globalist and universalist polity. Spengler must be credited, however, with pointing out that the frequently used concept 'world history', in reality encompasses an impressive array of diverse and opposing cultures without common denominator; each culture displays its own forms, pursues its own passions, and grapples with its own life or death. 'There are blossoming and ageing cultures', writes Spengler, 'peoples, languages, truths, gods and landscapes, just as there are young and old oak trees, pines, flowers, boughs, and peta;s--but there is no ageing mankind.'. For Spengler, cultures seem to be growing in sublime futility, with some approaching terminal illness, and others still displaying vigorous signs of life. Before culture emerged, man was an ahistorical creature; but he becomes again ahistorical and, one might add, even hostile to history: 'as soon as some civilisation has developed its full and final form, thus putting a stop to the living development of culture." (2:58; 2:38).

Spengler was convinced, however, that the dynamics of decadence could be fairly well predicted, provided that exact historical data were available. Just as the biology of human beings generates a well-defined life span, resulting ultimately in biological death, so does each culture possess its own ageing 'data', normally lasting no longer than a thousand years-- a period, separating its spring from its eventual historical antithesis, the winter, of civilisation. The estimate of a thousand years before the decline of culture sets in corresponds to Spengler's certitude that, after that period, each society has to face self-destruction. For example, after the fall of Rome, the rebirth of European culture started andes in the ninth century with the Carolingian dynasty. After the painful process of growth, self-assertiveness, and maturation, one thousand years later, in the twentieth century, cultural life in Europe is coming to its definite historical close.

As Spengler and his contemporary successors see it, Western culture now has transformed itself into a decadent civilisation fraught with an advanced form of social, moral and political decay. The First signs of this decay appeared shortly after the Industrial Revolution, when the machine began to replace man, when feelings gave way to ratio. Ever since that ominous event, new forms of social and political conduct have been surfacing in the West--marked by a widespread obsession with endless economic growth and irreversible human betterment--fueled by the belief that the burden of history can finally be removed. The new plutocratic elites, that have now replaced organic aristocracy, have imposed material gain as the only principle worth pursuing, reducing the entire human interaction to an immense economic transaction. And since the masses can never be fully satisfied, argues Spengler, it is understandable that they will seek change in their existing polities even if change may spell the loss of liberty. One might add that this craving for economic affluence will be translated into an incessant decline of the sense of public responsibility and an emerging sense of uprootedness and social anomie, which will ultimately and inevitably lead to the advent of totalitarianism. It would appear, therefore, that the process of decadence can be forestalled, ironically, only by resorting to salutary hard-line regimes.

Using Spengler's apocalyptic predictions, one is tempted to draw a parallel with the modern Western polity, which likewise seems to be undergoing the period of decay and decadence. John Lukacs, who bears the unmistakable imprint of Spenglerian pessimism, views the permissive nature of modern liberal society, as embodied in America, as the first step toward social disintegration. Like Spengler, Lukacs asserts that excessive individualism and rampant materialism increasingly paralyse and render obsolete the sense of civic responsibility. One should probably agree with Lukacs that neither the lifting of censorship, nor the increasing unpopularity of traditional value, nor the curtailing of state authority in contemporary liberal states, seems to have led to a more peaceful environment; instead, a growing sense of despair seems to have triggered a form of neo-barbarism and social vulgarity. 'Already richness and poverty, elegance and sleaziness, sophistication and savagery live together more and more,' writes Lukacs. Indeed, who could have predicted that a society capable of launching rockets to the moon or curing diseases that once ravaged the world could also become a civilisation plagued by social atomisation, crime, and an addiction to escapism? With his apocalyptic predictions, Lukacs similar to Spengler, writes: 'This most crowded of streets of the greatest civilisation; this is now the hellhole of the world.'

Interestingly, neither Spengler nor Lukacs nor other cultural pessimists seems to pay much attention to the obsessive appetite for equality, which seems to play, as several contemporary authors point out, an important role in decadence and the resulting sense of cultural despair. One is inclined to think that the process of decadence in the contemporary West is the result of egalitarian doctrines that promise much but deliver little, creating thus an economic-minded and rootless citizens. Moreover, elevated to the status of modern secular religions, egalitarianism and economism inevitably follow their own dynamics of growth, which is likely conclude, as Claude Polin notes, in the 'terror of all against all' and the ugly resurgence of democratic totalitarianism. Polin writes: 'Undifferentiated man is par excellence a quantitative man; a man who accidentally differs from his neighbours by the quantity of economic goods in his possession; a man subject to statistics; a man who spontaneously reacts in accordance to statistics'. Conceivably, liberal society, if it ever gets gripped by economic duress and hit by vanishing opportunities, will have no option but to tame and harness the restless masses in a Spenglerian 'muscled regime'.

Spengler and other cultural pessimists seem to be right in pointing out that democratic forms of polity, in their final stage, will be marred by moral and social convulsions, political scandals, and corruption on all social levels. On top of it, as Spengler predicts, the cult of money will reign supreme, because 'through money democracy destroys itself, after money has destroyed the spirit' (2: p.582; 2: p.464). Judging by the modern development of capitalism, Spengler cannot be accused of far-fetched assumptions. This economic civilisation founders on a major contradiction: on the one hand its religion of human rights extends its beneficiary legal tenets to everyone, reassuring every individual of the legitimacy of his earthly appetites; on the other, this same egalitarian civilisation fosters a model of economic Darwinism, ruthlessly trampling under its feet those whose interests do not lie in the economic arena.

The next step, as Spengler suggest, will be the transition from democracy to salutary Caesarism; substitution of the tyranny of the few for the tyranny of many. The neo-Hobbesian, neo-barbaric state is in the making:

Instead of the pyres emerges big silence. The dictatorship of party bosses is backed up by the dictatorship of the press. With money, an attempt is made to lure swarms of readers and entire peoples away from the enemy's attention and bring them under one's own thought control. There, they learn only what they must learn, and a higher will shapes their picture of the world. It is no longer needed--as the baroque princes did--to oblige their subordinates into the armed service. Their minds are whipped up through articles, telegrams, pictures, until they demand weapons and force their leaders to a battle to which these wanted to be forced. (2: p.463)

The fundamental issue, however, which Spengler and many other cultural pessimists do not seem to address, is whether Caesarism or totalitarianism represents the antithetical remedy to decadence or, orator, the most extreme form of decadence? Current literature on totalitarianism seems to focus on the unpleasant side effects of the looted state, the absence of human rights, and the pervasive control of the police. By contrast, if liberal democracy is indeed a highly desirable and the least repressive system of all hitherto known in the West--and if, in addition, this liberal democracy claims to be the best custodian of human dignity--one wonders why it relentlessly causes social uprootedness and cultural despair among an increasing number of people? As Claude Polin notes, chances are that, in the short run, democratic totalitarianism will gain the upper hand since the security to provides is more appealing to the masses than is the vague notion of liberty. One might add that the tempo of democratic process in the West leads eventually to chaotic impasse, which necessitates the imposition of a hard-line regime.

Although Spengler does not provide a satisfying answer to the question of Caesarism vs. decadence, he admits that the decadence of the West needs not signify the collapse of all cultures. Rather it appears that the terminal illness of the West may be a new lease on life for other cultures; the death of Europe may result in a stronger Africa or Asia. Like many other cultural pessimists, Spengler acknowledges that the West has grown old, unwilling to fight, with its political and cultural inventory depleted; consequently, it is obliged to cede the reigns of history to those nations that are less exposed to debilitating pacifism and the self-flagellating feelings of guilt that, so to speak, have become the new trademarks of the modern Western citizen. One could imagine a situation where these new virile and victorious nations will barely heed the democratic niceties of their guilt-ridden formser masters, and may likely at some time in the future, impose their own brand of terror that could eclipse the legacy of the European Auschwitz and the Gulag. In view of the turtles vicil and tribal wars all over the decolonized African and Asian continent it seems unlikely that power politics and bellicosity will disappear with the 'Decline of the West'; So far, no proof has been offered that non-European nations can govern more peacefully and generously than their former European masters. 'Pacifism will remain an ideal', Spengler reminds us, 'war a fact. If the white races are resolved never to wage a war again, the coloured will act differently and be rulers of the world'.

In this statement, Spengler clearly indicts the self-hating 'homo Europeanus' who, having become a victim of his bad conscience, naively thinks that his truths and verities must remain irrefutably turned against him. Spengler strongly attacks this Western false sympathy with the deprived ones--a sympathy that Nietzsche once depicted as a twisted form of egoism and slave moral. 'This is the reason,' writes Spengler, why this 'compassion moral', in the day-to day sense 'evolved among us with respect, and sometimes strived for by the thinkers, sometimes longed for, has never been realised' (I: p.449; 1: p.350).

This form of political masochism could be well studied particularly among those contemporary Western egalitarians who, with the decline of socialist temptations, substituted for the archetype of the European exploited worker, the iconography of the starving African. Nowhere does this change in political symbolics seem more apparent than in the current Western drive to export Western forms of civilisation to the antipodes of the world. These Westerners, in the last spasm of a guilt-ridden shame, are probably convinced that their historical repentance might also secure their cultural and political longevity. Spengler was aware of these paralysing attitudes among Europeans, and he remarks that, if a modern European recognises his historical vulnerability, he must start thinking beyond his narrow perspective and develop different attitudes towards different political convictions and verities. What do Parsifal or Prometheus have to do with the average Japanese citizen, asks Spengler? 'This is exactly what is lacking in the Western thinker,' continues Spengler, 'and watch precisely should have never lacked in him; insight into historical relativity of his achievements, which are themselves the manifestation of one and unique, and of only one existence" (1: p.31; 1: p.23). On a somewhat different level, one wonders to what extent the much-vaunted dissemination of universal human rights can become a valuable principle for non-Western peoples if Western universalism often signifies blatant disrespect for all cultural particularities.

Even with their eulogy of universalism, as Serge Latouche has recently noted, Westerners have, nonetheless, secured the most comfortable positions for themselves. Although they have now retreated to the back stage of history, vicariously, through their humanism, they still play the role of the indisputable masters of the non-white-man show. 'The death of the West for itself has not been the end of the West in itself', adds Latouche. One wonders whether such Western attitudes to universalism represent another form of racism, considering the havoc these attitudes have created in traditional Third World communities. Latouche appears correct in remarking that European decadence best manifests itself in its masochistic drive to deny and discard everything that it once stood for, while simultaneously sucking into its orbit of decadence other cultures as well. Yet, although suicidal in its character, the Western message contains mandatory admonishments for all non-European nations. He writes:

The mission of the West is not to exploit the Third World, no to christianise the pagans, nor to dominate by white presence; it is to liberate men (ands seven more so women) from oppression and misery. In order to counter this self-hatred of the anti-imperialist vision, which concludes in red totalitarianism, one is now compelled to dry the tears of white man, and thereby ensure the success of this westernisation of the world. (p.41)

The decadent West exhibits, as Spengler hints, a travestied culture living on its own past in a society of indifferent nations that, having lost their historical consciousness, feel an urge to become blended into a promiscuous 'global polity'. One wonders what would he say today about the massive immigration of non-Europeans to Europe? This immigration has not improved understanding among races, but has caused more racial and ethnic strife that, very likely, signals a series of new conflicts in the future. But Spengler does not deplore the 'devaluation of all values nor the passing of cultures. In fact, to him decadence is a natural process of senility that concludes in civilisation, because civilisation is decadence. Spengler makes a typically German distinction between culture and civilisation, two terms that are, unfortunately, used synonymously in English. For Spengler civilisation is a product of intellect, of completely rationalised intellect; civilisation means uprootedness and, as such, it develops its ultimate form in the modern megapolis that, at the end of its journey, 'doomed, moves to its final self-destruction' (2: p.127; 2: p. 107). The force of the people has been overshadowed by massification; creativity has given way to 'kitsch' art; genius has been subordinated to the terror reason. He writes:

Culture and civilisation. On the one hand the living corpse of a soul and, on the other, its mummy. This is how the West European existence differs from 1800 and after. The life in its richness and normalcy, whose form has grown up and matured from inside out in one mighty course stretching from the adolescent days of Gothics to Goethe and Napoleon--into that old artificial, deracinated life of our large cities, whose forms are created by intellect. Culture and civilisation. The organism born in countryside, that ends up in petrified mechanism (1: p.453; 1: p.353).

In yet another display of determinism, Spengler contends that one cannot escape historical destiny: 'the first inescapable things that confronts man as an unavoidable destiny, which no though can grasp, and no will can change, is a place and time of one's birth: everybody is born into one people, one religion, one social stays, one stretch of time and one culture.' Man is so much constrained by his historical environment that all attempts at changing one's destiny are hopeless. And, therefore, all flowery postulates about the improvement of mankind, all liberal and socialist philosophising about a glorious future regarding the duties of humanity and the essence of ethics, are of no avail. Spengler sees no other avenue of redemption except by declaring himself a fundamental and resolute pessimist:

Mankind appears to me as a zoological quantity. I see no progress, no goal, no avenue for humanity, except in the heads of the Western progress-Philistines...I cannot see a single mind and even less a unity of endeavours, feelings, and understanding in thsese barren masses people. (Selected Essays, p.73-74; 147).

The determinist nature of Spengler's pessimism has been criticised recently by Konrad Lorenzz who, while sharing Spengler's culture of despair, refuses the predetermined linearity of decadence. In his capacity of ethologist and as one of the most articulate neo-Darwinists, Lorenz admits the possibility of an interruption of human phylogenesis--yet also contends that new vistas for cultural development always remain open. 'Nothing is more foreign to the evolutionary epistemologist, as well, to the physician,' writes Lorenz, 'than the doctrine of fatalism.' Still, Lorenz does not hesitate to criticise vehemently decadence in modern mass societies that, in his view, have already given birth to pacified and domesticated specimens, unable to pursue cultural endeavours,. Lorenz would certainly find positive renounce with Spengler himself in writing:

This explains why the pseudodemocratic doctrine that all men are equal, by which is believed that all humans are initially alike and pliable, could be made into a state religion by both the lobbyists for large industry and by the ideologues of communism (p. 179-180).

Despite the criticism of historical determinism that has been levelled against him, Spengler often confuses his reader with Faustian exclamations reminiscent of someone prepared for battle rather than reconciled to a sublime demise. 'No, I am not a pessimist,' writes Spengler in Pessimism, 'for Pessimism means seeing no more duties. I see so many unresolved duties that I fear that time and men will run out to solve them' (p. 75). These words hardly cohere with the cultural despair that earlier he so passionately elaborated. Moreover, he often advocates forces and th toughness of the warrior in order to starve off Europe's disaster.

One is led to the conclusion that Spengler extols historical pessimism or 'purposeful pessimism' (Zweckpressimismus), as long as it translates his conviction of the irreversible decadence of the European polity; however, once he perceives that cultural and political loopholes are available for moral and social regeneration, he quickly reverts to the eulogy of power politics. Similar characteristics are often to be found among many pets, novelists, and social thinkers whose legacy in spreading cultural pessimism played a significant part in shaping political behaviour among Europrean conservatives prior to World War II. One wonders why they all, like Spengler, bemoan the decadence of the West if this decadence has already been sealed, if the cosmic die has already been cast, and if all efforts of political and cultural rejuvenation appear hopeless? Moreover, in an effort to mend the unmendable, by advocating a Faustian mentality and will to power, these pessimists often seem to emulate the optimism of socialists rather than the ideas of these reconciled to impending social catastrophe.

For Spengler and other cultural pessimists, the sense of decadence is inherently combined with a revulsion against modernity and an abhorrence of rampant economic greed. As recent history a has shown, the political manifestation of such revulsion may lead to less savoury results: the glorification of the will-to-power and the nostalgia of death. At that moment, literary finesse and artistic beauty may take on a very ominous turn. The recent history of Europe bears witness to how daily cultural pessimism can become a handy tool of modern political titans. Nonetheless, the upcoming disasters have something uplifting for the generations of cultural pessimists who's hypersensitive nature--and disdain for the materialist society--often lapse into political nihilism. This nihilistic streak was boldly stated by Spengler's contemporary Friedrich Sieburg, who reminds us that 'the daily life of democracy with its sad problems is boring but the impending catastrophes are highly interesting.'

Once cannot help thinking that, for Spengler and his likes, in a wider historical context, war and power politics offer a regenerative hope agains thee pervasive feeling of cultural despair. Yet, regardless of the validity of Spengler's visions or nightmares, it does not take much imagination observe in the decadence of the West the last twilight-dream of a democracy already grown weary of itself.

Content on the Traditional Britain Blog and Journal does not necessarily reflect the opinions of The Traditional Britain Group