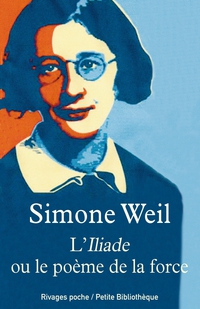

THE ILIAD, or the Poem of Force

(L’Iliade, ou le poeme de la force)

Ex: https://chazzw.wordpress.com

The true hero, the true subject, the center of the “Iliad” is force.

Thus opens Simone Weil’s essay. She calls the Iliad the purest and loveliest of mirrors for the way it shows force as being always at the center of human history. Force is that x that turns those who are subjected to it into a thing. As the Iliad shows us time and time again, this force is relentless and deadly. But force not only works upon the object of itself, its victims – it works on those who posses it as well. It is pitiless to both. It crushes those who are its victims, and it intoxicates those who wield it. But in truth, no man ever really posseses it. As the Iliad clearly shows, one day you may wield force, and the next day you are the object of it.

In this poem there is not a single man who does not at one time or another have to bow his neck to force.

Weil points out that the proud hero of Homer’s poem, the warrior, is first seen weeping. Agamemnon has purposely humiliated Achilles, to show him who is master and who is slave. Ah, but later it is Agamemnon who is seen weeping. Hector is later seen challenging the whole Greek army and they know fear. When Ajax calls him out, the fear is in Hector. As quickly as that. Later in the poem its Ajax who is fearful: Zeus the father on high, makes fear rise in Ajax [Homer]. Every single man in the Iliad (Achilles excepted) tastes a moment of defeat in battle.

Weil catches things, subtle things that show us the marvel of the Iliad. The tenet of justice being blind for instance, and its being meted out to all in the same way, without favoritism. He who lives by force shall die by force was established in the Iliad long before the Gospels recognized this truism.

Ares is just, and kills those who kill [Homer]

The weak and the strong both belong to the same species: the weak are never without some power, and the strong are never without some weakness. Achilles, of course, is Exhibit A. The powerful feel themselves indestructible, invulnerable. The fact of their power contains the seeds of weakness. Chickens, my friends, will always come home to roost. The very powerful see no possibility of their power being dimished – they feel it unlimited. But it is not. And this is where Weil gets deep into the heart of the matter. If we believe we are of the powerless then we see those who have what seems to be unlimited power as of another species, apart. And vice versa. The weak cannot possibly inherit the earth. They are …well. too weak, too different too apart, too unlike that powerful me. Dangerous thinking.

Thus it happens that those who have force on loan from fate count on it too much and are destroyed.

But at that moment in time, this seems inconceivable, failing to realize that the power they have is not inexhaustible, not infinite. Meeting no resistance, the powerful can only feel that their destiny is total domination. This is the very point where the domineering are vulnerable to domination. The have exceeded the measure of the force that is actually at their disposal. Inevitably they exceed it since they are not aware that it is limited. And now we see them commited irretrievably to chance; suddenly things cease to obey them. Sometimes chance is kind to them, sometimes cruel. But in any case, there they are, exposed, open to misfortune; gone is the armor of power that formerly protected their naked souls; nothing, no shield, stands between them and tears.

Overreaching man is for Weil the main subject of Greek thought. Retribution, Nemesis. These are buried in the soul of Greek epic poetry. So starts the discussion on the nature of man. Kharma. We think we are favored by the gods. Do we stop and consider that they think they are favored by the gods. If we do, we quickly (as do they) put it out of our heads. Time and time again in the see-saw battle that Homer relates to us, we see one side (or the other) have an honorable victory almost in hand, and then want more. Overreaching again. Hector imagines people saying this about him.

Overreaching man is for Weil the main subject of Greek thought. Retribution, Nemesis. These are buried in the soul of Greek epic poetry. So starts the discussion on the nature of man. Kharma. We think we are favored by the gods. Do we stop and consider that they think they are favored by the gods. If we do, we quickly (as do they) put it out of our heads. Time and time again in the see-saw battle that Homer relates to us, we see one side (or the other) have an honorable victory almost in hand, and then want more. Overreaching again. Hector imagines people saying this about him.

Weil writes chillingly on death. We all know that we are fated to die one day. Life ends and the end of it is death. The future has a limit put on it by that fact. For the soldier, death is the future. Very similar to the way a person struggling with a surely deadly disease looks at death. It’s his future. As I struggle to deal with my brain cancer, struggle for the way to align it with the life remaining to me, I realize that my future is already defined by my death which is straight ahead. The future is death. It’s very much in my thoughts. Generally we live with a realization that we all die, as I’ve said. But the very indeterminate nature of that death, of that murky future, allows us to put it out of our minds. We go about the task of living. Terminal diseases make us think about the task of dying.

Once the experience of war makes visible the possibility of death that lies locked up in each moment, our thoughts cannot travel from one day to the next without meeting death’s face.

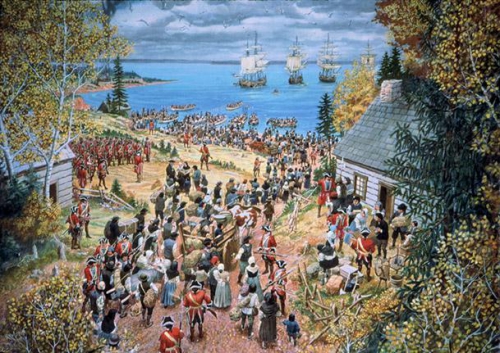

Weill tells us that the Iliad reveals to the reader the last secret of war. This secret is revealed in its similes. Warriors, those on the giving end of force, are turned into things. Things like fire, things like flood waters, things like heavy winds or wild beasts of the fields. But Homer has just enough examples of man’s higher aspirations, of his noble soul, to contrast with force, and give us what might be. Love, brotherhood, friendship. The seeds of these attributes, of these moments of grace, of these values in man, make the use of force by man all the more tragic and life denying.

I recall thinking as I read the Iliad that it was uncanny how many times I thought of the phrase ‘God is on our side’, so we shall prevail. The irony, or the bitter truth of this position is that the two opposing sides, if they had only one thing in common, it would be this simple belief: We are on the right side, and ‘they’ are on the wrong side.

Throughout twenty centuries of Christianity, the Romans and the Hebrews have been admired, read, imitated, both in deed and word; their masterpieces have yielded an appropriate quotation every time anybody had a crime they wanted to justify.

Simone Weill concludes with her belief that since the Iliad only flickers of the genius of Greek epic has been seen. Quite the opposite, she laments.

Perhaps they will yet rediscover the epic genius, when they learn that there is no refuge from fate, learn not to admire force, not to hate the enemy, not to scorn the unfortunate.

Amen to that, Simone.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg