“The basic experience of the Youth Movement was the conflict between the bourgeois world and individual life. It was also a conflict between generations, in which, strangely enough, the fathers were the liberals and the sons the conservatives. This was a marked reversal since the days of the earlier youth movement the Burschenschaften of 1815. Then the new generation, which had fought in the Wars of Liberation, was in the fore in the struggle for a unified German state and for constitutionalism. Now liberalism, so it seemed to the sons, had lost its vitality and had come to stand for a world of confinement and convention. The young generation was tired of the state and tired of constitutions just as the early conservatives had been distrustful of them. In the Youth Movement there was a touch of the anarchic. It was antiauthoritarian, but it was also in search of authority and allegiances. This was its conservatism.

The Youth Movement derived its conservatism from Nietzsche and the traditions of nineteenth century irrationalism. Nietzsche, Lagarde, Stefan George became its heroes and were read, quoted, imitated, and freely plagiarized. They had given sanction to the struggle between the generations. Nietzsche had called upon the “first generation of fighters and dragon-slayers” to establish the “Reich of Youth.” Lagarde had defended German youth against the complaint that it lacked idealism: “I do not complain that our youth lacks ideals: I accuse those men, the statesmen above all, who do not offer ideals to the young generation.” To a searching youth, the irrationalists, all experimenters in conservatism, pointed a way to a conservatism through rebellion and radicalism, thus setting the tone for a revolutionary conservatism. Hegel and Bismarck were squarely repudiated. And Nietzsche, in lieu of traditions long lost, postulated the “will of tradition” a variation only of the ominous “will of power” as the foundation of a new conservatism. All the more did Stefan George’s symbolism appeal to the young. They learned to see themselves as the “new nobility” of a “new Reich”:

New nobility you wanted

Does not hail from crown or scutcheon!

Men of whatsoever level

Show their lust in venial glances,

Show their greeds in ribald glances…

Scions rare of rank intrinsic

Grow from matter, not from peerage,

And you will detect your kindred

By the light within their eyes.

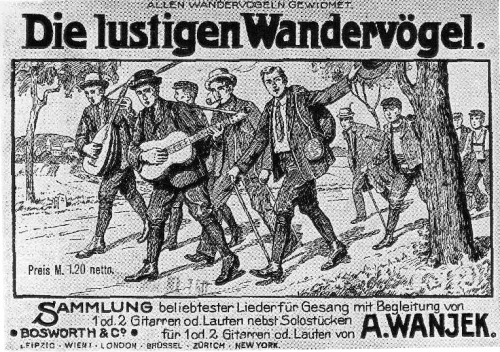

Twentieth century knights were they, united by secret codes. They claimed to be dedicated to a “mission”; more correctly they were in search of one. Heinrich Heine, had he lived to see those Wandervogel, would have called them “armed Nietzscheans.”

The revolutionary temper of the Youth Movement is evident from its famous declaration, formulated at a meeting near Kassel on the Hohen Meissner hill in October 1913. It stated that “Free German Youth, on their own initiative, under their own responsibility, and with deep sincerity, are determined independently to shape their own lives. For the sake of this inner freedom they will under any and all circumstances take united action…”.“

– Klemens Von Klemperer, “Germany’s New Conservatism: Its History and Dilemma in the Twentieth Century” (1968)

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.