Some international relations scholars and commentators are rediscovering that Eurasia is a geopolitical unit, a “supercontinent”, in the words of Bruno Maçães in his interesting new book The Dawn of Eurasia. Maçães traces the origins of the term Eurasia to Austrian geologist Eduard Suess in 1885, but the idea that Eurasia should be viewed as a single geopolitical unit is traceable to the great British geopolitical theorist Sir Halford Mackinder in a little-remembered article in 1890 entitled “The Physical Basis of Political Geography”.

Mackinder in that article subdivided Eurasia into the “Gulf Stream Region” (Europe) and the “Indo-Chinese” or “Monsoon” region (East, Central and South Asia) where two-thirds of the world’s population lived, and noted both the Silk Road and seafaring trade routes that linked Europe and Asia. In the early 20th century, Mackinder further developed the notion of Eurasia as the world’s dominant landmass and as a potential seat of a world empire.

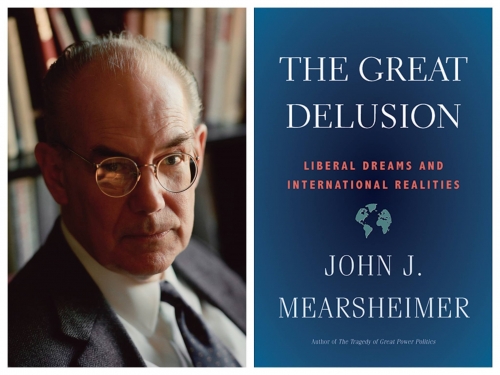

Maçães, who is currently a Senior Advisor at Flint Global in London, a Senior Fellow at Renmin University in Beijing and the Hudson Institute in Washington, and a former Portuguese Europe Minister, calls the political world of the 21st century the “new Eurasian world”, but, as noted above, there is really nothing “new” about it, at least in a geographical sense. Indeed, history’s greatest land empires—the Mongols, Napoleonic France, Nazi Germany, and the Soviet Union—were Eurasian. And, as Maçães notes, “[t]he border between Europe and Asia was always unstable, untenable and, for the most part, illusory.”

What then is “new” about the Eurasia of the 21st century that is resulting in a “new world order?”

What’s new is a shift in power from West to East.

What’s new, according to Maçães, is a shift in power—economic and political—from West to East. It is a shift in power from the western part of Eurasia to its eastern part. But it is also a shift in power from non-Eurasian powers—Britain and the United States—to Eurasian powers—especially China and India. This shift occurred, he believes, because Asia caught up with Europe and the West with respect to science, technology, and innovation; in a word, modernization. Maçães explains:

That the Europeans found themselves in a position to control practically the whole world was a direct result of a series of revolutions in science, economic production and political society whose underlying theme was the systematic exploration of alternative possibilities, different and until then unknown ways of doing things.

Asia embarked on a “fast embrace of modernity” such that modernization has become universal.

Maçães is quick to point out, however, that universal modernization is not equal in all societies and that there are “different models of modern society”. This is especially the case with respect to political models. Asian modernization does not mean that Asian nations will follow the liberal democratic path of Europe and the West. So while economic, scientific, and technological modernization is universal, political systems will remain different. Parag Khanna in his new book The Future is Asian urges Asian powers to reject Western liberal democracy in favor of what he calls “technocratic governance”, which he describes as a form of democratic-authoritarian government similar to Singapore’s.

The new world order flowing from universal modernization among rival nation-states will be characterized, writes Maçães, by “a struggle for mastery in Eurasia”. Again, there is nothing “new” about this, except some of the players. China and India are the most conspicuous rising powers, but Russia has staked its claim in the struggle, too.

The Belt and Road Initiative is “a race for power at the heart of the greatest landmass on earth.”

Maçães writes about his “six-month journey along the historical and cultural borders between Europe and Asia” to show that the borders are not real. He traveled to Azerbaijan, the Caucasus, and other places in the region between the Black and Caspian Seas. He highlights the growing importance of Caspian energy resources to Europe, China and Russia, and the growth of Central Asian cities that lie along the path of China’s new Silk Road. He describes China’s plan for a “new network of railways, roads, and energy and digital infrastructure linking Europe and China.” The Belt and Road Initiative, Maçães writes,has the ambition of creating the world’s longest economic corridor, linking the Asia-Pacific economic pole at the eastern end of Eurasia, and the European pole at its western end.

The land component of this initiative is complemented by the “Maritime Silk Road” that connects China to Europe via the South China Sea, the South Pacific and the Indian Ocean. “Together”, he writes, “the land and sea components will strive to connect about sixty-five countries.”

Maçães views China’s Belt and Road Initiative as more than an economic corridor. It risks, he writes, upsetting old geographical realities and evoking a nineteenth-century world of great-power rivalry, a race for power at the heart of the greatest landmass on earth.

Maçães believes that in the struggle for mastery of Eurasia, Russia is an important variable, and that the Trump administration recognizes this. While President Obama rhetorically pivoted to Asia, Maçães explains, President Trump is seeking to pivot to Eurasia. Trump, he writes, views Eurasia in Kissingerian terms—the United States should have better relations with China and Russia than they have with each other. Trump’s strategy, he believes, “would use closer relations with Russia to limit China’s growing power and influence.”

That is a very 19th-century view of the world, but it makes eminent geopolitical sense in the 21st century. Indeed, in Mackinder’s last article on the subject in 1943 in Foreign Affairs, he envisioned a global geopolitical balance between the North Atlantic nations (the US, Canada, and Western Europe), Russia, and the populous lands of South and East Asia. The result, he hoped, would be “[a] balanced globe of human beings.”

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg