What has got to be gotten over is the false idea that a hallucination is a private matter.

— P. K. Dick [1] [1]

There is no fiction. What is fiction today will be a fact tomorrow. A book written as a fictional story today comes out of the imagination of the one who wrote it, and will become a fact in the tomorrows.

— Neville [2] [2]

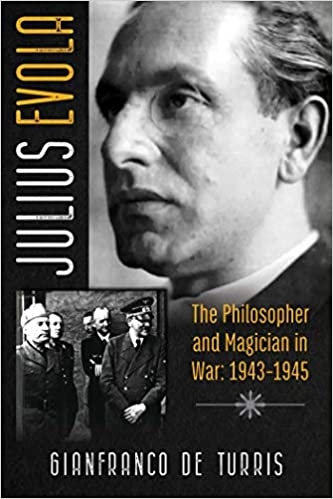

Gianfranco de Turris’ newly translated book on Julius Evola’s war years [3] [3] is a veritable secret archive of obscure and obscured information on Evola’s activities in the last two years of the Second World War and the immediate aftermath, all of which is used by the author to throw light on many occurrences that have remained poorly documented and, inevitably, subject to more or less informed speculation, if not outright gossip.

Gianfranco de Turris’ newly translated book on Julius Evola’s war years [3] [3] is a veritable secret archive of obscure and obscured information on Evola’s activities in the last two years of the Second World War and the immediate aftermath, all of which is used by the author to throw light on many occurrences that have remained poorly documented and, inevitably, subject to more or less informed speculation, if not outright gossip.

One of these is the injury Evola received in Vienna, which left him an invalid for the remainder of his life. Collin Cleary, in his review [4], gives a nice summary:

On January 21, 1945, Evola decided to take a walk through the streets of Vienna during an aerial bombardment by the Americans (and not the Soviets, as has been erroneously claimed). While he was in the vicinity of Schwarzenbergplatz, a bomb fell nearby, throwing Evola several feet and knocking him unconscious. He was found and taken to a military hospital. When the philosopher awoke hours later, the first thing he did was to ask what had become of his monocle. Once the doctors had finished looking him over, the news was not good. Evola was found to have a contusion of the spinal cord which left him with complete paralysis from the waist down. As Mircea Eliade notoriously said, the injury was roughly at the level of “the third chakra.” It resulted in Evola being categorized as a “100-percent war invalid,” which afforded him the small pension he received for the rest of his life.

An all-too-common tragedy of wartime. Yet with Evola, nothing is so simple. Speculation and rumor have swirled around this incident. If this is how Evola was injured, why was he engaged in such an apparently suicidal act (and indeed, “taking a walk . . . during an aerial bombardment” was actually a habit with him)? And if it wasn’t the cause, what was? As in the title of de Turris’ book, Evola is known as not only a philosopher but a magician: surely something spookier was involved? And indeed, since Evola was apparently in Vienna to examine Masonic documents, including rituals, the latter of which he intended to “rectify” and purify of anti-traditional elements, the idea of his being injured by an esoteric ritual gone wrong becomes possible (if one takes such things seriously).

De Turris deals with all these issues magisterially and has surely produced a definitive account (unless more documents turn up; he is a scrupulous scholar who admits when something is still unclear, and corrects his own earlier accounts when new information has appeared).

One amazing bit of information de Turris provides concerns novelizations of Evola’s situation, which inevitably take the Dan Brown path of giving magical accounts; no less than three, and two of them by Mircea Eliade! Both Il segerto del Graal by Paolo Virio (1955) and Diciannove rose by Eliade (1978) appeared after the incident (and in Eliade’s case after Evola’s death). The third novel, the first of Eliade’s two, is the most interesting; here is de Turris’ description:

It is also necessary to make reference to another novel by the Romanian author that is a most bewildering coincidence if not a real prophecy. Upon his return from his stay in India in 1931, Mircea Eliade would write some novels and short stories within that setting with its appropriate allusions; among this literary output is Il Segreto del Dottor Honigberger, published in 1940. The protagonist was a Saxon physician in the 1800s who had really existed. It first appeared in two parts in a magazine and a few months later, slightly but significantly expanded, in the form of a book accompanied by Notti a Serampore. The author makes reference to an inexperienced disciple who has remained paralyzed for having not known to thoroughly master the knowledge of his own discoveries on the spiritual plane when seeking to perfect a “yoga initiation.” The stupefying fact is that the name of this tragic character is J. E.! The young Mircea Eliade had known Julius Evola in Rome during his travels to Italy in the years 1927 to 1928, which was at the time of the Ur Group, and maintained a correspondence with him when he was in India. Is it perhaps possible that he just might have named the unfortunate spiritual researcher with the abbreviation J. E., since he was impressed by his personality and by his “occult” interests? Whatever it might be, the paralysis is described five years before the bombardment of Vienna, and the antecedents ascribed to it are the very rumors that surrounded Evola once he returned to Italy in 1951. Eliade probably had only learned of it on the occasion of another journey to the Italian Peninsula, where in 1952 he had another encounter with Evola. Or perhaps even after having only read Il cammino del cinabro [Evola gifted him a copy of the first edition in 1963]. Hence he consciously and deliberately made use of this for Diciannove rose. But to write of it before it had ever occurred in 1940. . . . [Author’s ellipsis, for spooky effect?]

So the stunning aspect in these novels is that both the authors, Paolo Virio and Mircea Eliade, knew what they were talking about. Both could boast of having sufficient experiences with initiatic methodologies, and both had long-lasting personal friendships with Julius Evola. . . . Had they deemed as insufficient the explanation of the bombing, considering it to be too prosaic, too banal for someone like him? And so they dreamed up in an equally effective and powerful evocation to describe the protagonist in their works.

You can buy James O’Meara’s book The Eldritch Evola here. [5]

You can buy James O’Meara’s book The Eldritch Evola here. [5]

Perhaps, but we should note again that this novel was published in 1940, “five years before the bombardment of Vienna, and the antecedents ascribed to [his injury] are the very rumors that surrounded Evola once he returned to Italy in 1951.” Surely a coincidence, says the man of common sense. Yet of course, Evola himself was not such a dreary man of sense, and as we’ll see he was certainly open to such esoteric interpretations.

Consider this [6]: Futility is a novella written by Morgan Robertson and published as Futility in 1898, and revised as The Wreck of the Titan in 1912.

It features a fictional British ocean liner Titan that sinks in the North Atlantic after striking an iceberg. Titan and its sinking are famous for similarities to the passenger ship RMS Titanic and its sinking fourteen years later. After the sinking of Titanic, the novel was reissued with some changes, particularly in the ship’s gross tonnage.

Although the novel was written before RMS Titanic was even conceptualized, there are some uncanny similarities between the fictional and real-life versions. Like Titanic, the fictional ship sank in April in the North Atlantic, and there were not enough lifeboats for all the passengers. There are also similarities in size (800 ft [244 m] long for Titan versus 882 ft 9 in [269 m] long for the Titanic), speed, and life-saving equipment. After the Titanic’s sinking, some people credited Robertson with precognition and clairvoyance, which he denied. Scholars attribute the similarities to Robertson’s extensive knowledge of shipbuilding and maritime trends.

As it happens, I was alerted to this historical oddity a while ago as a result of reading one of Neville’s lectures, “Seedtime and Harvest,” which articulates the principle that “there is no fiction [7].”

14 years before the actual harvest or that frightful event of the sinking of the Titanic a man in England wrote a book. He conceived this fabulous Atlantic liner and there he built her just like the Titanic, (only the Titanic was not built for 14 years) but he, in his imagination, conceived the liner of 800-ft. She was triple screw, she carried 3000 passengers, she carried few lifeboats because she was unsinkable; she could make 24 knots; and then one night he filled her to the brim with rich and complacent people, and on a cold winter night he sunk her on an iceberg in the Atlantic. 14 years later the White Star Line builds a ship. She is 800 ft., she is a triple screw, she can make 24 knots, she can carry 3000 passengers, she has not enough lifeboats for passengers but she, too, is labeled unsinkable. She is filled to capacity with the rich, if not complacent, but the rich, because her passenger list was worth in that day, when the dollar was one hundred cents, two hundred and fifty million dollars was the worth of the passenger list. Today [1956] it would be a billion dollars. All the wealth of Europe and the wealth of this country was sailing on that maiden voyage out of Southampton. Five nights at sea in this wonderful glorious ship and she went down on a cold April night on an iceberg.

Now that man wrote a book either to get something off his chest because he disliked the rich and the complacent, or he thought it might sell or he thought this is the means of bringing him a dollar as a writer. But, whatever was the motive behind his book which, by the way, he called Futility to show the utter futility of accumulated wealth, but the identical ship was built 14 years later and carried the same kind of a passenger list and went down in the same manner as the fictional ship.

Is there any fiction? There is no fiction! Tomorrow’s world is today’s fiction. Today’s world was yesteryear’s fiction — the dreams of men of yesteryear. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if I could talk with someone across space and just use a wire? And I couldn’t see that one: it would be a mile away beyond the range of my voice — then maybe five miles and maybe a thousand miles — fantastic dreams — then they came true. When they came true, suppose I could do it without the means of a wire. And it came true; suppose now I could do it not just in an audio sense but in a video sense. Suppose I could be seen? And that came true, but when they were conceived, they were all fictional, all unreal.

And how can this be [8]?

Now, am I responsible for others in my world? I certainly am! When I take my little mind, my little imagination and think because it’s mine — my Father gave it to me, that I can simply misuse it, it isn’t going to hurt another. I tell you you do have to use more control for the simple reason I am rooted in you and you are rooted in everyone and all of us are rooted in God. There is no separate individual detached being in my Father’s Kingdom. We are one. I am completely responsible for the use or misuse of my imagination.

Now, I’m sure all this just sticks in the craw of those self-styled “rationalists” or “materialists” out there (including many who idolize the political Evola and wish everyone would forget about all that magical stuff). I won’t try to gainsay that here, but as I said above, Evola certainly agreed with this basic idea (without going the full “we are all one” New Age route politically), [4] [9] and I think it’s worthwhile to put our rationalism “in parentheses,” as the phenomenologists would say [10], and explore some of the ramifications.

What Neville’s talking about is an extension of the notion of magical combat into the realm of the involuntary or accidental — as if you gave a monkey a machine gun. [5] [11] Guénon believed he himself had been paralyzed for six months due to such a magical attack in 1939, recovering only when an “evil influence” was deported from Egypt. On this basis, he suggested Evola “reflect upon it” and “see if something similar could not have been around you.” [6] [12] As Evola later recalled,

I told Guénon that a similar attack would be an unlikely cause in my case, not least because an extraordinarily powerful spell would have been necessary to cause such damage; for the spell would have had to determine a whole series of objective events, including the occurrence of the bombing raid, and the time and place in which the bombs were dropped. [7] [13]

Evola’s reasoning here is interesting, because Neville addresses exactly this point, and denies it; in fact, rejecting it is a key part of his “method for changing the future.” [8] [14] One is to imagine the end, being in the state of the desire satisfied; not the means. To dwell on the means is unnecessary and even counterproductive, as thereby one remains in the state of lack; [9] [15] instead, when the future state is imagined so clearly as to feel real, the larger world itself will arrange things in ways you could never have imagined. A “bridge of incidents” will be constructed for you to cross; your materialist friends will point to this sequence of “objective” events and call it “coincidence,” and claim it would have happened anyway. Indeed, since most of us have little control over our thoughts, we may have no recollection of the idle thought in the past that led to a current situation. [10] [16]

The more careful one is with what thoughts we allow ourselves to entertain, and the more outlandish the apparent means used to bring about a desired outcome, the more likely one is to make the leap from mere coincidence to meaningful coincidence — i.e. synchronicity.

Thus, Neville’s stories tend to involve improbable means; in his most famous story, “How Abdullah Taught Neville the Law [17],” Neville’s hoped-for escape from a New York City winter occurs when his brother “decides” to have to whole family together for Christmas, and sends him a ticket and expenses for a voyage back to Barbados. [11] [18] The family business — today’s massive Caribbean conglomerate, Goddard Enterprises [19] — is founded when, after his brother spends two years of lunch hours gazing at a business rival’s building, imagining his family name on the side, a stranger, “looking for a better return on his savings,” walks up with an offer to buy him the building [20]. His two brothers visit New York and want to see a sold-out production of Aida; Neville goes to the Met box office, foils a con man (because Neville’s tall enough to look over the man’s shoulder and recognize the short change scam he’s “attempting”), and is rewarded with VIP tickets [21].

I’ve used scare quotes because in each case a third party — brother, stranger, con man — thinks he is just going about his business, exercising his free will, when actually they are essential parts in the bridge of incidents invoked by Neville himself.

On the other hand, the lack of specific means — “a way you could never imagine” — leaves open the possibility of foul play. Neville consoles a follower who had wished to be rid of neighbor — who (consequently?) dies. [12] [22] Another listener asks point-blank if one can wish for someone’s death, and Neville sort of side steps in his answer: no one really wants someone to die, just to go away, which could involve a change of jobs or retirement to Florida. [13] [23] In general, one should only wish for the best, not only for oneself but for others — who, after all, are us as well. [14] [24]

In any event, there is no need to try to determine if someone, perhaps Eliade, launched a magical attack on Evola, perhaps inadvertently; Evola himself attributed a different, though related, supervening cause. Perhaps the best way to shift gears here is to again aver to our skeptical readers, who have no doubt already asked themselves: well, if Evola was such a great magician, why didn’t he just heal himself?

Remarkably, De Turris presents evidence that Evola simply didn’t want to. [15] [25] He quotes the recollections of a distinguished Orientalist:

“One day, probably in 1952, Colazza, Scaligero, and I had been to see Evola in his apartment in Corso Vittorio. I had noticed that Evola could move his legs, despite the paralysis that we knew he had. After visiting, we left Evola’s house. As we went down the stairs, I heard Scaligero saying to Colazza: ‘But Evola could not. . . .’ As he was talking about certain practices, a certain subtle operation, a kind of exercise to which Colazza answered suddenly, in an almost clipped tone: ‘Of course he could! But he doesn’t! He does not want to do it.’”

The professor was convinced that Evola could have resolved his partial invalidity, if he were willing to practice some exercises on the etheric or subtle body that were most definitely known by Colazza, Scaligero, and Evola himself. The reason why Evola did not want to operate in this direction remains a mystery and, for Professor Filippani, even this fact goes back to Evola’s “peculiar bad character.”

The abrupt but anguished response from the anthroposophist, Dr. Colazza, who the philosopher had asked for advice and explanations about his disability, makes it clear Evola possessed psychospiritual resources and an immeasurable inner being on the subtle plane to the point that he could “self-heal.” But he did not want to do it. One must ask why?

Indeed, we must; surely the only thing stranger than someone walking around during an aerial bombardment is that same person refusing to “self-heal.” What the professor calls Evola’s “bad character” was his stubborn refusal to take an interest in anything, however important, that, in fact, did not currently interest him; a character flaw he no doubt considered part of his prerogative as either an aristocrat or a genius. In particular, the three Anthroposophists who visited him may have tried to have him accept their assistance through what Evola’s UR group would have called a “magical chain,” [16] [26] exactly the sort of outside cause we have seen Neville discuss. [17] [27]

Indeed, we must; surely the only thing stranger than someone walking around during an aerial bombardment is that same person refusing to “self-heal.” What the professor calls Evola’s “bad character” was his stubborn refusal to take an interest in anything, however important, that, in fact, did not currently interest him; a character flaw he no doubt considered part of his prerogative as either an aristocrat or a genius. In particular, the three Anthroposophists who visited him may have tried to have him accept their assistance through what Evola’s UR group would have called a “magical chain,” [16] [26] exactly the sort of outside cause we have seen Neville discuss. [17] [27]

De Turris, however, suggests a more developed reason, which also brings us back to Neville. In a letter from 1947, Evola writes:

What is not clear to me is the purpose of the whole thing: I had in fact the idea — the belief if you want to call it, naive — that [when testing fate] one either dies or reawakens. The meaning of what has happened to me is one of confusion: neither one nor the other motive.

Evola will expand on this in The Path of Cinnabar:

What happened to me constitutes an answer that however wasn’t at all easy to interpret. Nothing changed, everything was reduced to a purely physical impediment that, aside from the practical annoying concerns and certain limitations of profane life, it neither affected nor effected me at all, my spiritual and intellectual activity not being in any way whatever altered or undermined. The traditional doctrine that in my writings I have often had the opportunity to expound — the one according to which there is no significant event in existence that was not wanted by us before birth — is also that of which I am intimately convinced, and such a doctrine I cannot but apply it also to the contingency now referred to. In reminding myself why I had wanted it is to however grasp its deepest meaning for the whole of my existence: this would have been, therefore, the only important thing, much more important than my recovery, to which I haven’t given any special weight. . . . But in this regard the fog has not yet lifted. Meanwhile, I have calmly adjusted myself to the situation, thinking humorously sometimes that perhaps this has to do with gods who have made the weight of their hands felt a little too heavy for my having joked around with them. [18] [28]

For some reason de Turris elides the following passage after “weight,” which seems to state the whole issue in a nutshell:

Besides, as I saw it, had I been capable of grasping the “memory” of such a wish by the light of knowledge, I would no doubt also have been capable of removing the physical handicap itself — if I had wished to.

The idea of our making a choice before birth – which Evola contrasts to mere amor fati, a la Nietzsche – can be found at least as far back as Plato’s Myth of Er [29]. [19] [30] And here again we can find a parallel with Neville’s teachings.

Unlike most New Thought teachers, who either rely on an accepted Christian terminology, or else posit a vague sort of Original Substance, Formless Substance, Formless Stuff, Thinking Substance, or Thinking Stuff, [20] [31] Neville offered something of an explanation, principally in the previously cited Out of This World: Thinking Fourth-Dimensionally [32]:

At every moment of our lives we have before us the choice of which of several futures we will choose. [21] [33]

How on Earth is that supposed to happen? Well, speaking of “Earth,” Neville posits a four-dimensional universe. [22] [34] The fourth dimension of course is time, and each of us — like everything in this three-dimensional world — is a sort of cross-section of a higher, fourth-dimensional being. Through the faculty of imagination — by a kind of controlled dreaming — one can rise to a level at which the whole time-line is laid out before us; we can both see the already determined future, and, by concentrated thought, enter it, and alter it.

Remember when we were talking about not worrying about the means? It’s the fourth-dimensional self that takes care of them, having means available we know not of.

Remember when we were talking about not worrying about the means? It’s the fourth-dimensional self that takes care of them, having means available we know not of.

The method works, because it is, in fact, “the mechanism used in the production of the visible world.” Mitch Horowitz uses quantum physics to explain this:

Neville likewise taught that the mind creates multiple and coexistent realities. Everything already exists in potential, he said, and through our thoughts and feelings we select which outcome we ultimately experience. Indeed, Neville saw man as some quantum theorists see the observer taking measurements in the particle lab, effectively determining where a subatomic particle will actually appear as a localized object. Moreover, Neville wrote that everything and everyone that we experience is rooted in us, as we are ultimately rooted in God. Man exists in an infinite cosmic interweaving of endless dreams of reality — until the ultimate realization of one’s identity as Christ.

In an almost prophetic observation in 1948, he told listeners: “Scientists will one day explain why there is a serial universe. But in practice, how you use this serial universe to change the future is more important.” More than any other spiritual teacher, Neville created a mystical correlate to quantum physics. [23] [35]

Neville has taken Evola’s “naïve idea” and projected it beyond a single, prenatal moment and onto every moment of our subsequent life. [24] [36] Evola believed “this truth should be sufficient to render all events that appear tragic and obscure less dramatic; for — as the Eastern saying goes — ‘life on Earth is but a journey in the hours of the night’: as such life is merely one episode set in a far broader framework that extends before and beyond life.” [25] [37] And for Neville, “This world, which we think so solidly real, is a shadow out of which and beyond which we may at any time pass.” [26] [38]

What, then, was the meaning of Evola’s injury, what he calls “the purpose of the whole thing”? De Turris admits this “has always remained a personal, private mystery, clearly and definitely one that is internal,” but tries to essay an “external response” based on “what happened after the end of the war.”

This man, immobilized in bed, wrote letters and articles with a copying pencil on a lectern placed leaning in front of him or at the typewriter seated at the desk in front of the window. After having been an “active” personality in every sense of the word, culturally and worldly, a mountaineer and traveler about the whole of Europe, he now engaged his intellectual and spiritual forces for those who, starting in the late forties, thought of reconstructing something. He used his symbolic vision, present since his first letters to friends back in 1946, “among the ruins” in Europe and Italy. He used a political movement of the right that kept in mind not only the negative but also the positive lessons of Fascism and National Socialism, in the way Evola and others had envisioned it to be after July 25 and September 8. An “immobile warrior,” as he was defined by his French biographer in an effective and suggestive image, and which — not without equivocations and misunderstandings — was an example for everyone. [27] [39]

You can buy James O’Meara’s book Green Nazis in Space! here. [40]

In short, Evola turned from direct engagement with the world to an attempt to influence and, moreover, inspire the next generation of European youth, the “men among the ruins,” still standing; or Spengler’s Roman soldier buried under the ashes of Pompeii because he was never ordered to leave.

Indeed, such was his influence that “he was tried by the Italian democracy for ‘defending Fascism,’ ‘attempting to reconstitute the dissolved Fascist Party’ and being the ‘“master’ and ‘inspirer’ of young Neo-Fascists. Like Socrates, he was accused of not worshipping the gods of the democracy and corrupting youth.” [28] [41] As John Morgan says, he became “something of a guru to the various Right-wing and neo-fascist groups which emerged in Italy in the first three decades after the war.” [29] [42]

In a previous essay, I briefly compared Evola’s last years to the dénouement of Hesse’s novel The Glass Bead Game. [30] [43] Joseph Knecht, the Game Master, disillusioned with an institution he finds to be intellectually sterile and doomed by its political naivety, resigns to become a tutor to the son of an old friend, Designori, who had already left for the “real” world, hoping to thereby provide some influence on the next generation. On their first morning stroll together, however, Knecht — unwilling to seem shy or cowardly — dives into a nearby lake and, overcome by cold and fatigue, drowns.

It seems anticlimactic as a novel, and futile and senseless as an act; as senseless, perhaps, as “questioning fate” by taking a walk during an aerial bombardment. The fact that Knecht dies in this effort, however, does not constitute failure. Hesse makes it clear from his portrait of Designori’s highly physical, yet still malleable and spiritually pure son Tito, that the incomplete work of Knecht and Designori might come to full fruition in him. A child of the world, Tito yet seems to sense the spiritual duty laid upon him by Knecht’s sacrifice, and the text suggests he will rise to meet it:

And since in spite of all rational objections he felt responsible for the Master’s death, there came over him, with a premonitory shudder of awe, a sense that this guilt would utterly change him and his life, and would demand much greater things of him than he had ever before demanded of himself. [31] [44]

Neville, of course, was no kshatriya. In fact, I have described him as a member of the haute bourgeoise — and that’s a good thing! The merchant is a legitimate class, very populous, especially today. [32] [45] Neville is an excellent model for the average man in today’s world; [33] [46] really the perfect mid-century American life, exactly what Mad Men’s Don Draper would have had if Matthew Weiner didn’t have an axe to grind. [34] [47]

Neville, of course, was no kshatriya. In fact, I have described him as a member of the haute bourgeoise — and that’s a good thing! The merchant is a legitimate class, very populous, especially today. [32] [45] Neville is an excellent model for the average man in today’s world; [33] [46] really the perfect mid-century American life, exactly what Mad Men’s Don Draper would have had if Matthew Weiner didn’t have an axe to grind. [34] [47]

His early first marriage, with a son, and second, lifelong marriage with a daughter [48], are a social idea, and compares favorably with many “alt-right” figures. He traveled between furnished, upscale residential hotels in New York City (Washington Square) and Los Angles (Beverly Hills), as he alludes to in his lectures, and the “success stories” he tells come from the same upper-middle-class milieus of nice houses, restaurants, and vacations. [35] [49] He was from a family of merchants, and mostly lived on various stipends from his family, as well as the high dividends paid out by the family-held corporation, even during the Depression. [36] [50] This enabled him to lecture with minimal admission costs to cover the rental of the hall, self-publish about ten small books, and allow — and encourage — his lectures to be taped without charge. [37] [51]

So much not a kshatriya that another of his most famous stories is how he imagined himself out of the Army! Despite being a middle-aged father of two and a non-citizen, Neville — perhaps due to the ex-dancer’s superb physical condition — was drafted in November 1942; effectively shanghaied into the fight against the forces Evola was willingly supporting as a noncombatant. [38] [52] How he extricated himself is one of his most interesting stories:

In 1942 in the month of December, this direction came down from Washington DC, any man over 38 is eligible for discharge, providing his superior officer allows it; if his superior officer, meaning his battalion commander disallows, there is no appeal beyond his battalion commander. You could not take it to say to the divisional commander, it stops with the battalion commander. This came down in 1942 in the month of December. They gave a deadline on it. This will come to an end on March 1st of 1943 so anyone 38 years, before the first of March, 1943 was eligible. All right. That is Caesar’s law. I got my paper, made it out. They had my record, my date. I was born in 1905 on the 19th of February, so I was 38 years old before the 1st of March of 1943 so I was eligible.

My battalion commander was Colonel Theodore Bilbo. His father was a senator from Mississippi. I turned [in my application for discharge], in four hours it came back “disapproved” and signed the colonel’s name. That night I went to sleep in the assumption that I am sleeping in my apartment house in New York City. I didn’t go through the door. I didn’t go through the window. I put myself on the bed. So I slept in that assumption. At 4:00/4:15 in the morning here came before my inner eye a piece of paper not unlike the one that I had signed that day. On the bottom of it was “disapproved.” Then came a hand from here down holding a pen and then the voice said to me “That which I have done I have done. Do nothing.” It scratched out disapproved and wrote in a big bold script “Approved”. And then I woke. I did nothing.

Nine days later that same colonel called me in. He said, “Close the door, Goddard.” “Yes, sir.” He said “Do you still want to get out of the army?” I said “Yes, sir.” He said “You’re the best-dressed man in this country, who wears the uniform of America,” I said, “Yes, sir.” “You still want to get out of the Army?” “Yes, sir.” Yessed him to death as I sat before him. He said, “All right, make out another application and you’ll be out of the Army today.”

I went back to my captain, told him what the colonel had said, made out another application and he signed it and that day I was out of the Army, honorably discharged. That’s all that I did. I went right into my home as a discharged soldier of our army and I’m a civilian. I slept that night in my home in New York City though physically my body was in Camp Polk, Louisiana. That’s how it works!

The colonel, when I went through the door that evening, he came forward and he said “Well, good luck Goddard. I will see you in New York City after we have won this war.” I said “Yes, sir.” And that was it. I share this with you to tell you how it works. This is not good and that is wrong. We are living in a world of infinite possibilities.” [39] [53]

Did this happen? Mitch Horowitz has established the external facts: that the Army discharged Neville in March, 1943 so as to “accept employment in an essential wartime industry”: delivering metaphysical lectures in Greenwich Village. [40] [54]

Remember, Neville was 38 years old, a non-citizen, had a wife and a young daughter; moreover, he fails to add, in the version above, that his son from his previous marriage was already drafted and serving at Guadalcanal. Apparently all that was being ignored now in the name of more cannon fodder for Churchill’s war. [41] [55] The military draft itself is a perfect example of the modern “reign of quantity,” in which all are regarded as interchangeable “individuals,” and I can see no reason why Neville, a true member of the merchant caste, should not have availed himself of a perfectly legal avenue of escape (“Caesar’s law”).

It’s also interesting to note that his commanding officer was a Col. Theodore Bilbo, son of Sen. Bilbo. [42] [56] One wonders if he shared his father’s interest in the resettlement of America’s negroes, [43] [57] and if Neville revealed to him that his guru, Abdullah, was involved with Marcus Garvey and Ethiopianism, [44] [58] leading him to look with favor on Neville’s application; could Neville have used not Abdullah’s teaching, but his connection with Ethiopianism, to smooth his eventual premature, but honorable, discharge from the Army?

But from our perspective here, the most interesting features of this story are, first, that Neville’s “essential wartime activity” was delivering metaphysical lectures — that is, instructions in his “method of changing the future” — which is not entirely unlike Evola’s wartime activities among the archives of secret societies that had been confiscated by the Germans; has there been any modern war in which magicians — Evola, Neville, Crowley — have played so great a role?

And secondly, this:

I had my 13 weeks’ basic training, and then when I came out, they gave me my citizenship papers. Back in 1922 I could have been an American, but I just didn’t have the time or the urge to get around to become a citizen; so I drifted on and drifted on and drifted on until after this little episode. That’s why I went into the Army, or I would still be drifting through, being a citizen of Britain. But now I’m an American by adoption. And they gave it to me because I did fulfill a 13-week training course in the American Army. So, I tell you, I know from experience how true this statement in [The Epistle of] James is. [45] [59]

Have we found here the key to the whole puzzling incident: the government’s dogged determination to press-gang [60] Neville like Billy Budd, only to then dangle a tantalizing offer of a get out of jail card, complete with citizenship? Once again, we see, perhaps, the unintended consequences of imagination; was the whole draft incident, seemingly absurd, the “bridge of incidents” leading to Neville’s desired naturalization as an American?

And in any event, Neville’s teaching evolved in a way very congruent to Evola’s aristocratic reserve and dedication to doing what has to be done.

After a mystical experience of being reborn from his own skull (Golgotha) in 1959, Neville’s teaching bifurcated: in addition to The Law (which became Oprah’s “Law of Attraction”), he also began to teach The Promise. The Law was given to enable you to live in the material world; the Promise was that you could then work to obtain union with God; a path suitable to the Dark Age:

After a mystical experience of being reborn from his own skull (Golgotha) in 1959, Neville’s teaching bifurcated: in addition to The Law (which became Oprah’s “Law of Attraction”), he also began to teach The Promise. The Law was given to enable you to live in the material world; the Promise was that you could then work to obtain union with God; a path suitable to the Dark Age:

One day you will be so saturated with wealth, so saturated with power in the world of Caesar, you will turn your back on it all and go in search of the word of God . . . I do believe that one must completely saturate himself with the things of Caesar before he is hungry for the word of God. [46] [61]

In short, Riding the Tiger. Interestingly, then as now, Neville’s listeners were more interested in The Law than in The Promise; they wanted him to return to stories about how people had obtained new cars and bigger houses. As Horowitz recounts [62] it:

Many listeners, the mystic lamented, “are not at all interested in its framework of faith, a faith leading to the fulfillment of God’s promise,” as experienced in his vision of rebirth. Audiences drifted away. Urged by his speaking agent to abandon this theme, “or you’ll have no audience at all,” a student recalled Neville replying, “Then I’ll tell it to the bare walls.” [47] [63]

Warrior or not, the picture of Neville standing on stage, lecturing to bare walls, recalls again Spengler’s Roman soldier, buried at Pompei because no order to stand down was given. From the start of his career:

He stood very still for an appreciable time, looking straight before him. Then he said, “Let us now go into the silence.” He squared himself on his feet, shut his eyes, flung his head sharply back, and became immobile. [48] [64]

And a few years from the end:

I know my time is short. I have finished the work I have been sent to do and I am now eager to depart. I know I will not appear in this three-dimensional world again for The Promise has been fulfilled in me. [49] [65] As for where I go, I will know you there as I have known you here, for we are all brothers, infinitely in love with each other. [50] [66]

It’s an attitude fully in keeping with New Thought, despite its reputation as encouraging an airy-fairy dreamworld attitude to life. Evola’s own attitude is actually not far from what the apostle of Positive Thinking, Norman Vincent Peale, would counsel:

The tough-minded optimist takes a positive attitude toward a fact. He sees it realistically, just as it is, but he sees something more. He views it as a challenge to his intelligence, to his ingenuity and faith. He seeks insight and guidance in dealing with the hard fact. He keeps on thinking. He knows there is an answer and finally he finds it. Perhaps he changes the fact, maybe he just bypasses it, or perhaps he learns to live with it. But in any case his attitude toward the fact has proved more important than the fact itself. [51] [67]

Or Biblical scholar — and Lovecraft authority — Robert M. Price:

We will never really finish. Our quests will be rudely suspended when the Grim Reaper taps us on the shoulder. “What the hell?” you say. Then why bother in the first place? Because it’s the chase. It’s the hunt. It’s acting without the fruits of action. You needn’t be bitter about it, like the fellow who wrote Ecclesiastes 2:21, “sometimes a man who has toiled with wisdom and knowledge and skill must leave all to be enjoyed by a man who did not toil for it. This also is vanity and a great evil.” No, it isn’t! Better that someone pick up where you left off! Pass the torch! Doing your part is all you can do, and that should be satisfaction enough. It is for me. [52] [68]

Speaking of the Bhagavad Gita — “acting without the fruits of action” — a somewhat similar attitude is demanded of us who would listen to Evola or Neville (just as Knecht’s sacrifice lays a burden on the pupil Tito); as John Morgan said in his speech on Evola:

The fact that we may lose the battle doesn’t mean that we are absolved of the responsibility of fighting it and standing for what is true. The best illustration of this that I know of comes from the Bhagavad Gita. . . .

And that’s how I see those of us here tonight. In spite of the million other things you could have been doing in this enormous and hyperactive city tonight, you decided to come here and meet with a group of some of the most hated people in America to listen to a lecture on Julius Evola. That clearly indicates that there’s something in you that has decided that there are more important things than just doing what everyone else expects you to do. So really, we’re already creating the “order” that Evola called for in order to preserve Tradition in the face of degeneracy. So let’s not despair about the latest headlines, but keep our heads up in the knowledge that, whatever happens, we are the ones who stand for what is timeless, and our day of victory will come, whether it is tomorrow or a thousand years from now. [53] [69]

Arguably, we have an easier time of it today; Neville allowed his lectures to be freely taped and transcribed, and they now live on through the intertubes; the books of both he and Evola are available in electronic formats you can read on the subway without fear of discovery. So ride that technological tiger! And as you do so, spare a thought for those who make them available, such as Counter-Currents, and consider what you can do to keep them standing [70].

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [71] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [72] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Notes

[1] [73] Exegesis, 15:87 (The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick; edited by Pamela Jackson and Jonathan Letham; Erik Davis, annotations editor (Houghton Mifflin, 2011).

[2] [74] “Believe It In [75],” Neville Goddard, 10/06/1969.

[3] [76] Gianfranco de Turris, Julius Evola: The Philosopher and Magician in War: 1943–1945 (Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2020), reviewed by Collin Cleary here [4].

[4] [77] See my Mysticism After Modernism: Crowley, Evola, Neville, Watts, Colin Wilson & Other Populist Gurus [78] (Melbourne, Australia: Manticore Press, 2020), especially the title essay, “Magick for Housewives: The Not So New and Really Quite Traditional Thought of Neville Goddard.”

[5] [79] Evola mocks materialists who think they have acquired “power” because they’ve devised a missile they can launch by pressing a button, while still being psychologically as underdeveloped as a monkey; see “The Nature of Initiatic Knowledge,” reprinted in Introduction to Magic: Rituals and Practical Techniques for the Magus (Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2001); compare: Dr. Ian Malcolm: “If I may. . . Um, I’ll tell you the problem with the scientific power that you’re using here, it didn’t require any discipline to attain it. You read what others had done and you took the next step. You didn’t earn the knowledge for yourselves, so you don’t take any responsibility for it. You stood on the shoulders of geniuses to accomplish something as fast as you could, and before you even knew what you had, you patented it, and packaged it, and slapped it on a plastic lunchbox, and now [bangs on the table] you’re selling it, you wanna sell it.” — Jurassic Park (Spielberg, 1993). Evola brought the original Ur and Krur articles with him to Vienna and was reworking them into the three volumes that would appear in 1955 as Introduction to Magic (and apparently bankrupted his publisher: de Turris, p. 145).

[6] [80] Letter to Evola; see de Turris, p. 148.

[7] [81] De Turris, loc. cit., quoting The Path of Cinnabar (London: Arktos, 2012), p. 184. I have substituted the latter translation by Sergio Knipe, as the one in de Turris seems garbled: “I explained to Guénon that nothing of the sort could be of value for my case and that, on the other hand, he would have had to come up with a most potent spell to cast because it would have had to determine a whole set of objective circumstances: the air strike, the moment, and the point of the bomb release, and so on.”

[8] [82] “The first step in changing the future is desire — that is: define your objective — know definitely what you want. Secondly: construct an event which you believe you would encounter following the fulfillment of your desire — an event which implies fulfillment of your desire — something that will have the action of self predominant. Thirdly: immobilize the physical body and induce a condition akin to sleep — lie on a bed or relax in a chair and imagine that you are sleepy; then, with eyelids closed and your attention focused on the action you intend to experience — in imagination — mentally feel yourself right into the proposed action — imagining all the while that you are actually performing the action here and now. You must always participate in the imaginary action, not merely stand back and look on, but you must feel that you are actually performing the action so that the imaginary sensation is real to you. It is important always to remember that the proposed action must be one which follows the fulfillment of your desire; and, also, you must feel yourself into the action until it has all the vividness and distinctness of reality.” Out of this World: Thinking Fourth-Dimensionally (1949); Chapter 1, “Thinking Fourth Dimensionally”; online here [83].

[9] [84] “The end of your journey is where your journey begins. When you tell me what you want, do not try to tell me the means necessary to get it, because neither you nor I know them. Just tell me what you want that I may hear you tell me that you have it. If you try to tell me how your desire is going to be fulfilled, I must first rub that thought out before I can replace it with what you want to be. Man insists on talking about his problems. He seems to enjoy recounting them and cannot believe that all he needs to do is state his desire clearly. If you believe that imagination creates reality, you will never allow yourself to dwell on your problems, for you will realize that as you do you perpetuate them all the more.” 10/6/1969, “Believe It In [75].”

[10] [85] “All cause is spiritual! Although a natural cause seems to be, it is a delusion of the vanishing vegetable memory. Unable to remember the moment a state was imagined, when it takes form and is seen by the outer eye its harvest is not recognized, and therefore denied.” Neville, “The Spiritual Cause [86],” May 3, 1968.

[11] [87] You can hear him narrate it here [88].

[12] [89] “If Any Two Agree. . . [90]” March 22, 1971. Rather like the classic tale “The Monkey’s Paw,” a woman’s wish to be rid of a disturbing neighbor seemingly results in his death, leaving three orphans. In this context, one might imagine someone fervently wishing “to be rid of this meddlesome Evola” or some such thing; a neighbor, an academic rival, perhaps a landlady?

[13] [91] “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest [92]?”

[14] [93] On another occasion, Neville’s idle wish to get out New York after a disappointing lecture seems to have sped up his mother’s not entirely unexpected death:

The war in Europe was on. England was at war. No ships were plying the Atlantic. They were going down faster than they could build them, and we were almost at war, and then came the month of August, and I received a cable from my family saying: “We didn’t tell you, because we knew you couldn’t come to Barbados. There aren’t any ships,” (and certainly in those days there were no planes) and they said: “Mother is dying. She’s been dying for two years, but now, this is it, and if you want to see her in this world once more, you’ve got to come now,” I mean, now. I received that cable in the morning, and my wife and I sailed the very next night. But it taught me a lesson: not to use this law idly, not to use it to escape, but to use it deliberately because you cannot escape from it. A series of events will mold themselves, across which you will walk, leading up to the fulfillment of that state. And so here I put myself, just to escape from the cold and the disappointment of the evening, in Barbados of all places. Then something happens, and I am compelled to make the journey, the last place in the world we intended to go. And we sailed at midnight, and got there four and a half days later on this “Argentine” ship. (It was an American ship, but it was called the Argentine.) Mother dies, as they all said she would, and I returned to the States with the knowledge of what I had done and began to teach it.

“Faith [94],” 7/22/1968.

[15] [95] “The first step in changing the future is desire — that is: define your objective — know definitely what you want.” Neville, Out of This World, loc. cit.

[16] [96] See Magic, op. cit., especially “Opus Magicum: Chains” by “Luce.”

[17] [97] Evola’s relations with Anthroposophy are a puzzle to me; the UR and KRUR group included disciples of Steiner, and Evola maintained friendly relations with them, as with these three; see Magic, op. cit., “Preface: Julius Evola and the UR Group” by Renato del Ponte. His Sintesi di dottrina della razza even presents two photos of Steiner to illustrate the Aryan “solar” type. Yet officially, as a “traditionalist,” Evola had to treat Anthroposophy as yet another grave “deviation” and “counter-tradition” worthy of extermination, even by the National Socialists. Was he ambivalent to Steiner because of the similarity of their intellectual development — from German Idealism to esotericism? (Both essentially claimed to have completed the system of German Idealism [98]). Was he afraid of being accused of hypocrisy; or of having to admit, if the treatment had succeeded, that Steiner was a legitimate psychic researcher?

[18] [99] De Turris, p. 166; this translation of a passage from Cinnabar would correspond to p. 183 of the abovementioned English translation. Again, this seems garbled; “neither affected nor effected me” is nonsense, but Knipe renders it as simply as “remained unaffected.”

[19] [100]

The end of the Republic is somewhat disconcerting. It ends with a strange myth about the afterlife. In this myth, people have the potential to choose the kind of life that they would like lead in their next incarnation. The dialogue concludes on this oddly apolitical note. But I want to argue that actually the whole purpose of the Republic is to lead up to this issue of choosing one’s life, of what kind of life is most choiceworthy.

[20] [103] All terms used at various times by Wallace D. Wattles [104], author of The Science of Getting Rich and various similar books.

[21] [105] Out of This World, op. cit., Chapter One, “Thinking Fourth-Dimensionally.”

[22] [106] This, we’ll see, is the “serial universe” of quantum physics, or the “block-universe” of Michael Hoffman, who posits that the ancient Mystery Religions used psychoactive or “entheogenic” drugs to induce a vision of this state of total determinism and loss of agency, then proposed a liberating Savior, such as Mithras or Christ; see, generally, the research collected at egodeath.com [107]. Neville finds freedom rather than determinism here. If Neville were more than fitfully in a philosophical mood, he might admit that our preference in futures is “determined” as well, but might insist that the only meaningful notion of “freedom” is “free to do what we in fact want, unhindered” rather than “free to choose, include what to want,” the so-called liberum arbitrium. As he says in Feeling is the Secret: “Free will is only freedom of choice.”

[23] [108] “In essence, more than eighty years of laboratory experiments show that atomic-scale particles appear in a given place only when a measurement is made. Quantum theory holds that no measurement means no precise and localized object, at least on the atomic scale. In a challenge to our deepest conceptions of reality, quantum data shows that a subatomic particle literally occupies an infinite number of places (a state called “superposition”) until observation manifests it in one place. In quantum mechanics, an observer’s conscious decision to look or not look actually determines what will be there.” All quotes from Horowitz, “A Cosmic Philosopher,” in At Your Command: The First Classic Work by the Visionary Mystic Neville (New York: Snellgrove Publications, 1939; Tarcher Cornerstone Editions, 2016), reviewed here [109] (and reprinted in Mysticism After Modernism).

[24] [110] Ironically, Neville also insists that “Creation is finished,” meaning that all possibilities are already there, four-dimensionally, and need only be chosen in order to be actualized; no “work” is needed to “bring them about.” See “Faith [111],” where Neville compares his doctrine to Richard Feynman [111], who had recently received the Nobel Prize: “I didn’t know it as a scientist. I knew it as a mystic.” Feynman states in a paper from 1949 that “We must now conclude that the entire concept that man held of the universe is false. We always believed that the future developed slowly out of the past. Now, with this concept which we have seen and photographed, we must now conclude that the entire space-time history of the world is laid out, and we only become aware of increasing portions of it successively.”

[25] [112] Path of Cinnabar, p. 230.

[26] [113] Out of This World, loc. cit. Cf. Blake, as frequently quoted by Neville: “All that you behold, though it appears without, it is within, in your imagination of which this world of mortality is but a shadow.” If all this seems opaque, maybe you should see Nolan’s new film, Tenet; a commenter on Trevor Lynch’s review [114] says “Tenet is about belief. The main character is not conscious in what he does, yet his deeper self is looking out for him. Time doesn’t exist to his deeper self, only the present. There’s no point in trying to rationalise or moralise it all, what happens is what happens and that is that; much like life. Be in touch with your spirit, act in accordance with it, possess plentitude and be the true protagonist of your own world. You are complete, a part of existence and exactly where you need to be. Such is freedom. Surrender.”

[27] [115] De Turris, 167-68; he also refers the reader to his Elogio e difesa di Julius Evola: Il barone e it terrroristi (Rome: Edizioni Mediterrranee, 1997).

[28] [116] E. Christian Kopff, “Julius Evola, An Introduction” in Julius Evola, A Traditionalist Confronts Fascism: Selected Essays(London: Arktos, 2015).

[29] [117] See “What Would Evola Do? [118]”, the text of the talk delivered to The New York Forum.

[30] [119] See “Two Orders, Same Man: Evola, Hesse [120],” reprinted in Mysticism After Modernism, op. cit.

[31] [121] Hermann Hesse, The Glass Bead Game, translated from the German Das Glasperlenspiel by Richard and Clara Winston, with a Foreword by Theodore Ziolkowski (New York: Bantam, 1970), p. 425.

[32] [122] Culturally, at least; in the current economy, of course, Neville’s lifestyle seems more out of reach.

[33] [123] There’s no “sin” in being a merchant. Sure, some picturesque versions of Hinduism would claim (re)birth in a lower caste is some kind of punishment, but that’s just what you’d expect a “high” caste person to claim, isn’t it? Evola rejected such “moralistic” accounts of karma — remember, every significant event in one’s life is chosen before birth; he even disparaged Heidegger’s claim that “authentic” “Dasein” must feel “guilty” over its “thrownness” as mere disguised Christianity (see his Ride the Tiger, chapter 15). As Nicholas Jeelvy says [124] about Boomer who “just want to grill”:

Do understand that I’m not knocking these people. They were born with average or below-average IQ and a weaker will than others. This is something they have zero control over. Low IQ and low thumos aren’t crimes. These people very prudently do not want to be involved in politics — they’ve neither the ability nor the inclination. Indeed, they are forced into politics by the republican-democratic system and the concordant liberal culture of “the good citizen” who is engaged with grand ideas. Really, the best these people can muster is local politics, which is why they expect small institutions to scale up. To them, the American federal government is a massive homeowner’s association and the FBI is their local sheriff’s department writ large. Small minds (which are small through no fault of their own) cannot comprehend the nature of macroentities. If they knew what we know about globohomo’s various institutions and agendas, they would be so thoroughly demoralized that they’d either be too depressed to leave their homes or the human submission instinct would kick in and they’d immediately convert to globohomo.

[34] [125] For more on Don Draper, see my End of an Era: Mad Men and the Ordeal of Civility (San Francisco: Counter-Currents, 2015) as well as more recent essays here on Counter-Currents.

[35] [126] After the war, Evola was given lifetime use of an apartment in Rome by a princely admirer.

[36] [127] He left Barbados for New York City at seventeen, eventually became a successful professional dancer on Broadway [128], but also working such jobs as an elevator operator. “I made thousands in a year, and spent it in a month.” Evola boasted of never receiving a paycheck, but this is difficult to reconcile with the evidence de Turris presents of his desperate letters to various officials to try to continue his “stipend” from the Fascist government as the latter collapsed, as well as his journalistic activities; a “paycheck” may suggest subservience to an employer, but Evola’s “stipend” was hardly passive income; if he was a “Baron,” it was more in the style of “Baron” Corvo’s: fiercely independent, but often hand-to-mouth.

[37] [129] “With Neville there’s nothing to join, nothing to buy.” — Mitch Horowitz.

[38 [130]] [130] Evola, though a veteran, was unable to rejoin the Italian military forces because, feeling himself to be “more fascist than the fascists,” he had never joined the party, which was now required for service; see de Turris, p. 69.

[39] [131] “The Secret of the Sperm,” 1965. Hear Neville tell it at 17:50 here [132].

[40] [133] “A Cosmic Philosopher,” pp. 83-84. The lectures are covered in a typically snarky article in The New Yorker (from September 11, 1943!), “A Thin Blue Flame on the Forehead,” scanned here [134].

[41] [135] Even the frickin’ Chinese emperor in Mulan only drafts her elderly father because he has no military age boys.

[42] [136] See Beau Albrecht’s discussion of Sen. Bilbo’s book Take Your Choice, “Part One: Strange Times Ahead [137]” and “Part Two: Stop the Hate [138]!”

[43] [139] See Kerry Bolton, “Ethiopia Pacific Movement: Black Separatists, Seditionists, & How “White Supremacists” Stymied Back-to-Africa,” Part I [140] and Part II [141].

[44] [142] Horowitz’s speculations on the identity of the mysterious Abdullah are in “A Cosmic Philosopher.”

[45] [143] “The Perfect Law of Liberty [144],” 4/2/71. The Epistle of James reads: “Be doers of the word, and not hearers only, deceiving yourself. For he who is a hearer of the word, and not a doer, he is like one who looks into the mirror and sees his natural face; and then he goes away and at once forgets what he looks like. But he who is a doer, he looks into the perfect law, the Law of Liberty, and perseveres. And when he does that, he is blessed in his doing.” (Chapter One).

[46] [145] Mitch Horowitz notes “This passage sounds a note that resonates through various esoteric traditions: One cannot renounce what one has not attained. To move beyond the material world, or its wealth, one must know that wealth. But to Neville — and this became the cornerstone of his philosophy — material attainment was merely a step toward the realization of a much greater and ultimate truth.” See “A Cosmic Philosopher.”

[47] [146] Op. cit.

[48] [147] “A Thin Blue Flame,” p. 64.

[49] [148] “Criswell departed this dimension in 1982” — Ed Wood (Tim Burton, 1992), final credit sequence. Criswell, a very Neville-like figure, also appears in Ed Wood’s last “legit” film, Night of the Ghouls [149] (1957, released 1984), in which a phony psychic (not Criswell!) gets his comeuppance when it turns out he really can raise the dead; again, be careful what you wish for.

[50] [150] “No Other God [151],” 5/10/1968.

[51] [152] Have a Great Day: Daily Affirmations for Positive Living by Norman Vincent Peale (Ballantine, 1985); September 2.

[52] [153] Holy Fable Volume 2: The Gospels and Acts Undistorted by Faith by Robert M. Price (Mindvendor, 2017).

[53] [154] “What would Evola Do [155]?”

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Gianfranco de Turris’ newly translated book on Julius Evola’s war years

Gianfranco de Turris’ newly translated book on Julius Evola’s war years

Indeed, we must; surely the only thing stranger than someone walking around during an aerial bombardment is that same person refusing to “self-heal.” What the professor calls Evola’s “bad character” was his stubborn refusal to take an interest in anything, however important, that, in fact, did not currently interest him; a character flaw he no doubt considered part of his prerogative as either an aristocrat or a genius. In particular, the three Anthroposophists who visited him may have tried to have him accept their assistance through what Evola’s UR group would have called a “magical chain,”

Indeed, we must; surely the only thing stranger than someone walking around during an aerial bombardment is that same person refusing to “self-heal.” What the professor calls Evola’s “bad character” was his stubborn refusal to take an interest in anything, however important, that, in fact, did not currently interest him; a character flaw he no doubt considered part of his prerogative as either an aristocrat or a genius. In particular, the three Anthroposophists who visited him may have tried to have him accept their assistance through what Evola’s UR group would have called a “magical chain,”  Remember when we were talking about not worrying about the means? It’s the fourth-dimensional self that takes care of them, having means available we know not of.

Remember when we were talking about not worrying about the means? It’s the fourth-dimensional self that takes care of them, having means available we know not of.

Neville, of course, was no kshatriya. In fact, I have described him as a member of the haute bourgeoise — and that’s a good thing! The merchant is a legitimate class, very populous, especially today.

Neville, of course, was no kshatriya. In fact, I have described him as a member of the haute bourgeoise — and that’s a good thing! The merchant is a legitimate class, very populous, especially today.

After a mystical experience of being reborn from his own skull (Golgotha) in 1959, Neville’s teaching bifurcated: in addition to The Law (which became Oprah’s “Law of Attraction”), he also began to teach The Promise. The Law was given to enable you to live in the material world; the Promise was that you could then work to obtain union with God; a path suitable to the Dark Age:

After a mystical experience of being reborn from his own skull (Golgotha) in 1959, Neville’s teaching bifurcated: in addition to The Law (which became Oprah’s “Law of Attraction”), he also began to teach The Promise. The Law was given to enable you to live in the material world; the Promise was that you could then work to obtain union with God; a path suitable to the Dark Age:

L'auteur explique l'échec historique de la contre-révolution par plusieurs raisons, que nous pouvons toutefois regrouper dans une seule catégorie, relative aux techniques de communication modernes, bien trop délaissées par les penseurs contre-révolutionnaires, «largement incapables d'utiliser des méthodes modernes, une organisation, des slogans, des partis politiques et la presse» (p. 179). C'est d'ailleurs grâce à leurs écrits que les révolutionnaires ont imposé leurs idées, jusque y compris dans le camp adverse : «Á mesure que les années passaient, les idées proposées par le parti révolutionnaire paraissaient de plus en plus attrayantes, non pas en raison de leurs mérites intrinsèques, mais parce qu'elles imprégnaient le climat intellectuel, acquéraient un monopole, isolaient les idées contraires en arguant de leur modération pour prouver leur impotence» (p. 59). Cette idée n'est à proprement parler pas vraiment neuve, puisque Taine puis Maurras l'ont développée avec quelques nuances, le premier critiquant la décorrélation de plus en plus prononcée entre la réalité et les discours évoquant cette dernière (2), le second affirmant que la Révolution française ne s'était pas produite le 14 juillet 1789 mais, comme l'écrit Molnar, qu'«elle s'est faite bien avant au tréfond[s] de l'esprit et de la sensibilité populaires, imprégnés des écrits des philosophes» (p. 65). D'une certaine manière, cette thèse fut aussi développée par le général Giraud qui dans un article paru durant l'été 1940 attribua une partie de la défaite française à la littérature, coupable à ses yeux d'avoir sapé les bases de la nation, puis par Jean Raspail dans son (trop) fameux

L'auteur explique l'échec historique de la contre-révolution par plusieurs raisons, que nous pouvons toutefois regrouper dans une seule catégorie, relative aux techniques de communication modernes, bien trop délaissées par les penseurs contre-révolutionnaires, «largement incapables d'utiliser des méthodes modernes, une organisation, des slogans, des partis politiques et la presse» (p. 179). C'est d'ailleurs grâce à leurs écrits que les révolutionnaires ont imposé leurs idées, jusque y compris dans le camp adverse : «Á mesure que les années passaient, les idées proposées par le parti révolutionnaire paraissaient de plus en plus attrayantes, non pas en raison de leurs mérites intrinsèques, mais parce qu'elles imprégnaient le climat intellectuel, acquéraient un monopole, isolaient les idées contraires en arguant de leur modération pour prouver leur impotence» (p. 59). Cette idée n'est à proprement parler pas vraiment neuve, puisque Taine puis Maurras l'ont développée avec quelques nuances, le premier critiquant la décorrélation de plus en plus prononcée entre la réalité et les discours évoquant cette dernière (2), le second affirmant que la Révolution française ne s'était pas produite le 14 juillet 1789 mais, comme l'écrit Molnar, qu'«elle s'est faite bien avant au tréfond[s] de l'esprit et de la sensibilité populaires, imprégnés des écrits des philosophes» (p. 65). D'une certaine manière, cette thèse fut aussi développée par le général Giraud qui dans un article paru durant l'été 1940 attribua une partie de la défaite française à la littérature, coupable à ses yeux d'avoir sapé les bases de la nation, puis par Jean Raspail dans son (trop) fameux  Il serait pour le moins difficile de dénier à Thomas Molnar la justesse de tels propos, y compris si nous devions tracer quelque parallèle avec notre propre époque, où triomphent ces «intellectuels des classes moyennes» (p. 108) qui à force de cocktails et de mauvais livres cherchent à s'émanciper de leur caste, pour fréquenter les grands, ou ceux qu'ils considèrent comme des grands, tout en n'affectant qu'un souci fallacieux de ce qu'ils méprisent au fond par-dessus tout et qu'ils sont généralement vite prêts à qualifier du terme méprisant (dans leur bouche) de peuple. Ce peuple est instrumentalisé, et ce n'est que par tactique que les intellectuels révolutionnaires peuvent donner l'impression de le flatter, voire de le respecter : «Ce qui est essentiel, les révolutionnaires ont rapidement compris que bien que 1789 ait ouvert la porte du pouvoir aux masses, celles-ci ne l'utiliseront jamais pour elles-mêmes, mais permettront seulement qu'il passe entre les mains de ces nouveaux privilégiés que sont les entraîneurs de foules, les faiseurs d'opinion et les idéologues» (p. 119). Finalement, la révolution n'est pas grand-chose, si nous nous avisions de la séparer de ses béquilles, que Thomas Molnar appelle «sa méthode de propagation dans tous les coins de la société» (p. 110) et, surtout, l'élevage quasiment industriel de ces intellectuels si remarquablement définis par

Il serait pour le moins difficile de dénier à Thomas Molnar la justesse de tels propos, y compris si nous devions tracer quelque parallèle avec notre propre époque, où triomphent ces «intellectuels des classes moyennes» (p. 108) qui à force de cocktails et de mauvais livres cherchent à s'émanciper de leur caste, pour fréquenter les grands, ou ceux qu'ils considèrent comme des grands, tout en n'affectant qu'un souci fallacieux de ce qu'ils méprisent au fond par-dessus tout et qu'ils sont généralement vite prêts à qualifier du terme méprisant (dans leur bouche) de peuple. Ce peuple est instrumentalisé, et ce n'est que par tactique que les intellectuels révolutionnaires peuvent donner l'impression de le flatter, voire de le respecter : «Ce qui est essentiel, les révolutionnaires ont rapidement compris que bien que 1789 ait ouvert la porte du pouvoir aux masses, celles-ci ne l'utiliseront jamais pour elles-mêmes, mais permettront seulement qu'il passe entre les mains de ces nouveaux privilégiés que sont les entraîneurs de foules, les faiseurs d'opinion et les idéologues» (p. 119). Finalement, la révolution n'est pas grand-chose, si nous nous avisions de la séparer de ses béquilles, que Thomas Molnar appelle «sa méthode de propagation dans tous les coins de la société» (p. 110) et, surtout, l'élevage quasiment industriel de ces intellectuels si remarquablement définis par  L'écrivain contre-révolutionnaire, quoi qu'il affirme, reste irrévocablement marqué au fer du provincialisme et, précise Thomas Molnar, est accablé par la mauvaise conscience de ceux «qui n'ont pratiquement jamais entendu répéter leurs paroles, vu reprendre leurs idées» (p. 174) : «il ne représente au regard de l'histoire qu'un moment peut-être brillant, mais passé, donc isolé, déposé loin du lit principal du fleuve» (p. 122), alors que, en face de lui, vainqueur qui n'a même pas eu besoin de mener un combat, se dresse l'intellectuel révolutionnaire, un de ces hommes «perpétuellement déchirés entre l'action et la réflexion, le bureau du philosophe et les barricades du révolutionnaire, la prose résignée du sceptique et l'allure de David devant Goliath, le mépris de l'esthète devant le chaos et l'enthousiasme du guerillero dans le feu de l'action» (pp. 126-7), description qui pourrait sans aucune difficulté s'appliquer à la majorité de nos propres penseurs révolutionnaires et même, sans doute, aux rares qui font profession de penseurs contre-révolutionnaires ou, disent les pions universitaires, d'

L'écrivain contre-révolutionnaire, quoi qu'il affirme, reste irrévocablement marqué au fer du provincialisme et, précise Thomas Molnar, est accablé par la mauvaise conscience de ceux «qui n'ont pratiquement jamais entendu répéter leurs paroles, vu reprendre leurs idées» (p. 174) : «il ne représente au regard de l'histoire qu'un moment peut-être brillant, mais passé, donc isolé, déposé loin du lit principal du fleuve» (p. 122), alors que, en face de lui, vainqueur qui n'a même pas eu besoin de mener un combat, se dresse l'intellectuel révolutionnaire, un de ces hommes «perpétuellement déchirés entre l'action et la réflexion, le bureau du philosophe et les barricades du révolutionnaire, la prose résignée du sceptique et l'allure de David devant Goliath, le mépris de l'esthète devant le chaos et l'enthousiasme du guerillero dans le feu de l'action» (pp. 126-7), description qui pourrait sans aucune difficulté s'appliquer à la majorité de nos propres penseurs révolutionnaires et même, sans doute, aux rares qui font profession de penseurs contre-révolutionnaires ou, disent les pions universitaires, d'