You can get hold of the copy of The Glass Bees I read here.

Ernst Jünger was one of the true luminaries of the intellectual Right in the 20th century. A popular hero of the First World War, famous for his memoir of the conflict entitled The Storm of Steel, he became aligned with the German conservative revolutionary movement in the interbellum years, and as such advocated a radical, authoritarian, militarist nationalism. This being said, he never made the fatal gesture Heidegger made, and was never associated with National Socialism; his relationship with Nazism began as coolly ambivalent, progressing into antipathy and finally open hostility (he was even peripherally involved with 20 July Plot to assassinate Hitler). This being said, his contribution to political theory outside his initial context was, essentially, minimal. However, he was regarded as a figure of great literary stature in post-war Europe. He was a prolific novelist, and his incredibly long lifespan (over a century) gave him an enviable vantage point to comment from: he was a grown man when the German Empire collapsed, he was present during the rise and fall of the Third Reich, and lived to see the reunification of Germany (comfortably outliving the German Democratic Republic). His fans included a variety of contradictory figures, including Hitler, Goebbels, Francois Mitterand, Thomas Mann and Bertolt Brecht. As well as writing, he was also a well-educated botanist and entomologist. He was even one of the very earliest experimenters with LSD. He was a man who embodied the very paradoxes and contradictions of recent European existence.

Ernst Jünger was one of the true luminaries of the intellectual Right in the 20th century. A popular hero of the First World War, famous for his memoir of the conflict entitled The Storm of Steel, he became aligned with the German conservative revolutionary movement in the interbellum years, and as such advocated a radical, authoritarian, militarist nationalism. This being said, he never made the fatal gesture Heidegger made, and was never associated with National Socialism; his relationship with Nazism began as coolly ambivalent, progressing into antipathy and finally open hostility (he was even peripherally involved with 20 July Plot to assassinate Hitler). This being said, his contribution to political theory outside his initial context was, essentially, minimal. However, he was regarded as a figure of great literary stature in post-war Europe. He was a prolific novelist, and his incredibly long lifespan (over a century) gave him an enviable vantage point to comment from: he was a grown man when the German Empire collapsed, he was present during the rise and fall of the Third Reich, and lived to see the reunification of Germany (comfortably outliving the German Democratic Republic). His fans included a variety of contradictory figures, including Hitler, Goebbels, Francois Mitterand, Thomas Mann and Bertolt Brecht. As well as writing, he was also a well-educated botanist and entomologist. He was even one of the very earliest experimenters with LSD. He was a man who embodied the very paradoxes and contradictions of recent European existence.Children, in particular, were held spellbound [by his films]. Zapparoni had dethroned the old stock figures of the fairy tales...Parents even complained that their children were too preoccupied with him.

[My father] had led a quiet life, but at the end he hadn't been too happy either. Lying sick in bed, he said to me: "My boy, I am dying at just the right moment." Saying this, he gave me a sad, worried look. He had certainly foreseen many things.

This is a deeply reactionary novel, and doesn't make for easy reading. Jünger's writing meanders, straying into lengthy digressions into his narrator's memory; his pace is languid, virtually glacial in fact. Although his prose is beautiful, even poetic, it feels incredibly indulgent and is often, frankly, dull. Very little happens as such in the novel, the bulk of it simply being Richard's recollections. And yet, what is curious is how this achingly slow piece of writing is able to convey the sheer speed with which modernity did away with the old world. The narrator, like Jünger, grew up in a world were the horse was still yet to be rendered obsolete by the automobile.

This is a deeply reactionary novel, and doesn't make for easy reading. Jünger's writing meanders, straying into lengthy digressions into his narrator's memory; his pace is languid, virtually glacial in fact. Although his prose is beautiful, even poetic, it feels incredibly indulgent and is often, frankly, dull. Very little happens as such in the novel, the bulk of it simply being Richard's recollections. And yet, what is curious is how this achingly slow piece of writing is able to convey the sheer speed with which modernity did away with the old world. The narrator, like Jünger, grew up in a world were the horse was still yet to be rendered obsolete by the automobile. Human perfection and technical perfection are incompatible. If we strive for one, we must sacrifice the other...Technical perfection strives toward the calculable, human perfection toward the incalculable. Perfect mechanisms...evoke both fear and a titanic pride which will be humbled not by insight but only by catastrophe.

What is curious here is that before the Second World War, Jünger advocated Germany's complete embracing of the technological age as the only way it could find victory in the next war. He felt that it was Germany and Austria-Hungary's traditional, aristocratic hierarchy that prevented it from being able to properly mobilise itself in the total way the more levelled, egalitarian societies of the democracies were capable of doing (he discusses this in his work Total Mobilisation), and only by accepting the levelling effects of technological modernity could Germany once again find itself triumphant. Perhaps by the time of writing The Glass Bees Jünger had simply become disenchanted with the fury of warfare.

Elsewhere Richard, and maybe Jünger, speaks of the loss of the simple 'joy' of labour, of working the earth, of harvesting crops, of the well-deserved rest at the end of the long day, and how this has been traded in for labour that is certainly easier, and leisure time that is longer, but doesn't carry the same weight of satisfaction. The fear that we have lost much and gained little except damnation in return is the central theme of this book.

Zapparoni himself, in fact, has utilised his vast wealth and power to create a private world at first seemingly devoid of the artefacts that have made his name. He has a residence located within the grounds of his plant (which Bruce Sterling, in his introduction, remarks is not dissimilar to the campus feeling of Silicon Valley) in the form of a converted abbey. Richard explores its private library, finding books on Rosicrucianism and other occult sciences, and is later sent down the path to a cottage that comes close to the very Platonic Form of idyllic country residences. What is curious here is that this retreat from modernity has only been made possible by Zapparoni's very success at the practices and theories that Richard feels have destroyed the simple authenticity of the old world. How might this be read? Perhaps Jünger is suggesting that the only way back into the world that has been lost is to pass through the modern one, presuming we are capable of surviving it, and to use its mechanisms and ingenuity to recreate a new version of the old.

There's a feeling of resignation in this novel. Jünger isn't really calling on us to take up arms against the machines. His constant allusions to astrology suggest that he feels that what we now find ourselves in was, somehow, inevitable. It is our bad luck to find ourselves in the midst of it, but a way out might be found if we can weather the storm of the new. This being said, Richard repeatedly describes his attitude as 'defeatist'. Perhaps the more subtle suggestion Jünger is making here is that things only became inevitable when we decided we can't stop them.

I'm left feeling torn by this book. I share Jünger's concerns about the insidious nature of these devices we're now surrounded by, and yet the past he (or Richard) is seemingly appealing to is one that is forever out of reach, and if we were to find ourselves in it, it wouldn't be what we wanted. Consider the above statement about how now modern war doesn't kill one cleanly, that we now have the mutilated, dismembered wounded: we can equally well read this as 'Human technical ingenuity is now such that it can protect us, admittedly only limitedly, from the extremities of human malice.'

The question posed by modernity is one that has not yet had a satisfactory answer. Indeed, the question itself has yet to be fully formulated. Jünger's contribution to understanding the condition that we find ourselves in is an important one. If nothing else, he can remind us how incredibly recent all of this still is. Up until only very recently, there were people alive who'd fought in the war of Kings, Kaisers and Tsars, witnessed the rise of all the great and terrible varieties of attempted Utopia the last century produced, saw a human being walk upon the surface of the Moon (an image which disturbed Heidegger no end), and died in the age of Facebook.

It really is anyone's guess where this will all lead.

2016 Reading List Progress

2. Sacred Drift: Essays on the Margins of Islam by Peter Lamborn Wilson

3. Notes from the Underground by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

4. United States of Paranoia by Jesse Walker

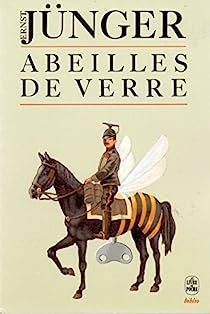

La même approche de la science et de la technologie considérées comme "dérangeantes" transparaît dans le court roman d'Ernst Jünger, Abeilles de verre, paru en 1957. Des abeilles de verre, c'est-à-dire de minuscules automates intelligents, peuplent les jardins de l'industriel Zapparoni (un autre Italien) où le protagoniste Richard - un vétéran de guerre issu d'un monde simple aux traditions axées sur l'honneur et aux valeurs perdues - s'est retrouvé à la recherche d'un emploi. Dans les jardins de Zapparoni, enrichis par la conception et la construction de machines technologiquement avancées, telles celles qui dominent aujourd'hui le monde, Richard observe la "symétrie effrayante", pour citer William Blake, des abeilles de verre et de leur physiologie hypertechnologique qui, loin d'améliorer ou de perfectionner la nature (imparfaite en soi, comme le souligne Jünger dans nombre de ses œuvres), nous rappelle que plus la technologie progresse, plus elle devient efficace, et que plus la technologie progresse, plus l'humanité involue et vice versa), elles l'appauvrissent, et finalement la dévastent - les fleurs touchées par les "abeilles de verre" sont en effet destinées à périr car elles sont privées de pollinisation croisée.

La même approche de la science et de la technologie considérées comme "dérangeantes" transparaît dans le court roman d'Ernst Jünger, Abeilles de verre, paru en 1957. Des abeilles de verre, c'est-à-dire de minuscules automates intelligents, peuplent les jardins de l'industriel Zapparoni (un autre Italien) où le protagoniste Richard - un vétéran de guerre issu d'un monde simple aux traditions axées sur l'honneur et aux valeurs perdues - s'est retrouvé à la recherche d'un emploi. Dans les jardins de Zapparoni, enrichis par la conception et la construction de machines technologiquement avancées, telles celles qui dominent aujourd'hui le monde, Richard observe la "symétrie effrayante", pour citer William Blake, des abeilles de verre et de leur physiologie hypertechnologique qui, loin d'améliorer ou de perfectionner la nature (imparfaite en soi, comme le souligne Jünger dans nombre de ses œuvres), nous rappelle que plus la technologie progresse, plus elle devient efficace, et que plus la technologie progresse, plus l'humanité involue et vice versa), elles l'appauvrissent, et finalement la dévastent - les fleurs touchées par les "abeilles de verre" sont en effet destinées à périr car elles sont privées de pollinisation croisée.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

THE Glass Bees is an introspective novel about a quiet but dignified cavalry officer called Richard. Unable to adjust to life after war and needing money, he applies for a security job at the headquarters of the mysterious oligarch Zapparoni. Confronted with mechanical and psychological trials, the dream becomes a nightmare, and Richard is forced to contemplate his place in the

THE Glass Bees is an introspective novel about a quiet but dignified cavalry officer called Richard. Unable to adjust to life after war and needing money, he applies for a security job at the headquarters of the mysterious oligarch Zapparoni. Confronted with mechanical and psychological trials, the dream becomes a nightmare, and Richard is forced to contemplate his place in the