Giovanni Gentile: Fascism’s Ideological Mastermind

Ex: http://magnagrece.blogspot.com/

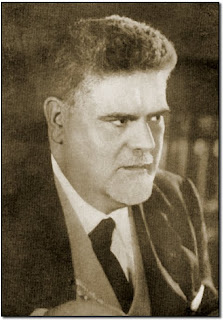

Professore Giovanni Gentile: the “Philosopher of Fascism.”

“Philosophy triumphs easily over past, and over future evils, but present evils triumph over philosophy.” – François de La Rochefoucauld: Maxims, 1665

In writing the history of a country or of an ethnos, all too often even the most well-meaning people are tempted out of patriotism to embellish the truth by either building up the good or omitting certain ‘unsavory’ facts about the past. On an emotional level this is understandable. After all, in a certain sense an ethnic group is a vastly extended family. The country, on the other hand, can be considered a sizable prolongation of the borders of one’s home. Who but the crassest enjoys speaking ill of home and family?

Nevertheless, if one wishes to strive for accuracy and objectivity in their writings, one must inevitably confront the specter of those who, during the course of their lives, engaged in actions that today go against the grain of established social mores. Otherwise, one risks being exposed to the charge of chauvinism (or worse).

It has been the stated purpose of this writer to show the reader how his people, the DueSiciliani, have carved out a place for themselves in this world in spite of the loss of their homeland, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, to the forces of the Piedmontese and their allies in 1861. Thus far, I and other like-minded folk posting on this blog have written of the commendable members of our people who have significantly added to Western Civilization through their contributions to the arts, sciences, philosophy (and even sports).

Men like Ettore Majorana, Salvator Rosa, Vincenzo Bellini and “the Nolan”, Giordano Bruno have unquestionably made this world better by being in it.

Similarly, we have written of those whose legacies provoke more ambivalent feelings. Men like Paolo di Avitabile and Michele Pezza, the legendary “Fra Diavolo”, led lives that to this day are considered controversial.

It now falls to this writer the hapless task of telling the tale of one of our own who went down “the road less traveled” to a decidedly darker place in the chapters of history – among the creators of 20th century totalitarian movements. As the reader will soon see, this journey cost him friends, a loftier place in the history books, and eventually his life!

Giovanni Gentile was born in the town of Castelvetrano, Sicily on May 30th, 1875 to Theresa (née Curti) and Giovanni Gentile. Growing up, his grades were so good he earned a scholarship to the University of Pisa in 1893. Originally interested in literature, his soon turned to philosophy, thanks to the influence of Donato Jaja. Jaja in turn had been a student of the Abruzzi neo-Hegelian idealist Bertrando Spaventa (1817-1883). Jaja would “channel” the teachings of Spaventa to Gentile, upon whom they would find a fertile breeding ground.

During his studies he found himself inspired by notable pro-Risorgimento Italian intellectuals such as Giuseppe Mazzini, Antonio Rosmini-Serbati and Vincenzo Gioberti. However, he also found himself drawn to the works of German idealist and materialist philosophers like Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Karl Marx, Friedrich Nietzsche and especially Georg Hegel. He graduated from the University of Pisa with a degree in philosophy in 1897.

He completed his advanced studies at the University of Florence, eventually beginning his teaching career in the lyceum at Campobasso and Naples (1898-1906).

Benedetto Croce

Beginning in 1903, Gentile began an intellectual friendship with another noted philosopher from il sud: Benedetto Croce. The two men would edit the famed Italian literary magazine La critica from 1903-22. In 1906 Gentile was invited to take up the chair in the history of philosophy at the University of Palermo. During his time there he would write two important works: The Theory of Mind as Pure Act (1916) and Logic as Theory of Knowledge (1917). These works formed the basis for his own philosophy which he dubbed “Actual Idealism.”

Giovanni Gentile’s philosophy of Actual Idealism, like Marxism, recognized man as a social animal. Unlike the Marxists, however, who viewed community as a function of class identity, Gentile considered community a function of the culture and history in a nation. Actual Idealism (or Actualism) saw thought as all-embracing, and that no one could actually leave their sphere of thinking or exceed their own thought. This contrasted with the Transcendental Idealism of Kant and the Absolute Idealism of Hegel.

He would remain at the University of Palermo until 1914, when he was invited to the University of Pisa to fill the chair vacated by the death of his dear friend and mentor, Donato Jaja. In 1917, he wound up at the University of Rome, where in 1925 he founded the School of Philosophy. He would remain at the University until shortly before his murder.

After Italy’s humiliating defeat at the disastrous Battle of Caporetto in November, 1917, Gentile took a greater interest in politics. A devoted Nationalist and Liberal; he gathered a group of like-minded friends together and founded a review, National Liberal Politics, to push for political and educational reform.

Gentile’s writings and activism attracted the attention of future Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini. Immediately after his famous “March on Rome” at the end of October, 1922, Mussolini invited Gentile to serve in his cabinet as Minister of Public Instruction. He would hold this position until July, 1924. Surviving records show that on May 31st, 1923 Giovanni Gentile formally applied for membership in the partito nazionale fascista, the National Fascist Party of Italy.

With his new cabinet position Gentile was given full authority by Mussolini to reform the Italian educational system. On November 5th, 1923 he was appointed senator of the realm, a representative in the Upper House of the Italian Parliament. Gentile was now at the pinnacle of his political influence. With the power and prestige granted him by his new office, he began the first serious overhaul of public education in Italy since the Casati Law was passed in 1859.

Gentile saw in Mussolini’s authoritarianism and nationalism a fulfillment of his dream to rejuvenate Italian culture, which he felt was stagnating. Through this he hoped to rejuvenate the Italian “nation” as well. As Minister of Public Instruction Gentile worked laboriously for 20 months to reform what was most certainly an antiquated and backward system. Though successful in his endeavor, ironically, it was the enactment of his plan that caused his political influence to wane.

In spite of this, Mussolini continued to grant honors on him. In 1924, after resigning his post as Minister, “Il Duce” invited him to join the “Commission of Fifteen” and later the “Commission of Eighteen” basically in order to figure out how to make Fascism fit into the Albertine Constitution, the legal document that governed the state of Italy since its formation after the infamous Risorgimento in 1861.

On March 29th, 1925 the Conference of Fascist Culture was held at Bologna, in northern Italy. The précis of this conference was the document: the Manifesto of the Fascist Intellectuals. It was an affirmation of support for the government of Benito Mussolini, throwing a gauntlet down to critics who questioned Mussolini’s commitment to Italian culture. Among its signatories were Giovanni Gentile (who drew up the document), Luigi Pirandello (who wasn’t actually at the conference but publicly supported the document with a letter) and the Neapolitan poet, songwriter and playwright Salvatore Di Giacomo.

It was that last name that provoked a bitter dispute between Gentile and his erstwhile friend and mentor, Benedetto Croce. Responding with a document of his own on May 1st, 1925, the Manifesto of the Anti-Fascist Intellectuals, Croce made public for all to see his irreconcilable split (which had been brewing for some time) with the Fascist Party of Italy…and Giovanni Gentile. In his document he dismissed Gentile’s work as “…a haphazard piece of elementary schoolwork, where doctrinal confusion and poor reasoning abound.” The two men would never collaborate again.

From 1925 till 1944 Gentile served as the scientific director of the Enciclopedia Italiana. In June of 1932 in Volume XIV he published, with Mussolini’s approval (and signature) and over the Roman Catholic Church’s objections, the Dottrina del fascismo (The Doctrine of Fascism). The first part of the Dottrina, written by Gentile, was his reconciling Fascism with his own philosophy of Actual Idealism, thereby forever equating the two.

Giovanni Gentile approved of Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935. Though he found aspects of Hitler’s Nazism admirable, he disapproved of Mussolini allying Italy with Germany, believing Hitler’s intentions could not be trusted and that Italy would wind up becoming a vassal state. His views on this were shared by General Italo Balbo and Count Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini’s son-in-law and Foreign Minister. Nevertheless, Gentile continued to support Mussolini. Since he recognized that Italy was a polity but not a nation in the true sense of the word, he believed “Il Duce’s” iron-fisted rule to be the only thing sparing the Italian pseudo-state from civil war.

With the collapse of Italy’s Fascist regime in September, 1943 and Mussolini’s rescue by Hitler’s forces, Gentile joined his emasculated master in exile at the so-called Italian Social Republic; an ad hoc puppet state created by Hitler in an ultimately futile attempt to shore up his rapidly crumbing 1,000-year Reich. Even then, he served as one of the principal intellectual defenders of what was obviously a failed political experiment.

On April 15, 1944 Professore Giovanni Gentile was murdered by Communist partisans led by one Bruno Fanciullacci. Ironically, he was gunned down leaving a meeting where he had argued for the release of a group of anti-Fascist intellectuals whose loyalty was suspect. He was buried in the Church of Santa Croce in Florence where his remains lie, perhaps fittingly, next to those of Florentine philosopher and writer Niccolò Machiavelli.

As one might imagine, after his death Gentile’s name was scorned if not forgotten entirely by historians. In recent years, however, scholars have begun to re-examine his legacy. Political theorist A. James Gregor (née Anthony Gimigliano), a recognized expert on Fascist and Marxist thought and himself an American of Southern Italian descent, believes that Gentile actually exerted a tempering influence on Italian Fascism’s proclivities towards violence as a political tool. This, he argues, is one (of several) of the reasons why Mussolini’s Italy never indulged in the more draconian excesses of Hitler’s regime.

Even his former friend and colleague Benedetto Croce later recognized the superior quality of Gentile’s scholarship and the quantity of his publications in the history of philosophy. Yet he differed sharply from him in political ideology and temperament. While both men forsook any loyalty to i Due Sicilie in favor of the pan-Italian illusion of the Risorgimento, they disagreed mightily as to the nature of the Italian state and to what course it should pursue.

For Gentile the actual idealist, the state was the supreme ethical entity; the individual existing merely to submit and merge his will and reason for being to it. Rebellion against the state in the name of ideals was therefore unjustifiable on any level. To Gentile, Fascism was the natural outgrowth of Actual Idealism.

Croce the neo-Kantian, on the other hand, argued forcefully the state was merely the sum of particular voluntary acts expressed by individuals (who were the center of society) and recorded in its laws. To Croce, Gentile’s metaphysical concepts regarding the state approached mysticism.

Thus, while both men have sadly been largely forgotten, even in the intellectual circles they once traversed, Croce’s legacy survives in a much better light than the man he once called friend.

Niccolò Graffio

Further reading:

- A. James Gregor: Giovanni Gentile: Philosopher of Fascism; Transaction Publishers, 2001.

- Giovanni Gentile and A. James Gregor (transl): Origins and Doctrine of Fascism: With Selections from Other Works; Transaction Publishers, 2002.

- M.E. Moss: Mussolini’s Fascist Philosopher: Giovanni Gentile Reconsidered; Peter Lang Publishing, Inc., 2004.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg