Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov (1899-1987), the best English speaking Russian writer of the 20th century, a brilliant novelist, poet and translator, stands fully apart from the national literary school. His modern language went so far from the traditional Slavic mentality that some critics even don’t want to consider him a great Russian thinker. Nabokov’s biography gives certain reasons for it.

He was born into a noble family with aristocratic European roots. His grandfather was Minister of Justice under Alexander II who married a young baroness Marie von Korff. His father, Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov, was a well-known liberal statesman, a member of the first Russian Parliament and one of the leaders of anti-Bolshevik opposition. Being an undisguised “westerner” and Anglofile (his favourite author was Alexander Herzen) Vladimir Dmitrievich invited an English nurse for his son.

Thus Vladimir Nabokov became a bilingual from the baby age. At the age of five he began learning French. And when the family moved from St. Petersburgh to Berlin, in 1919, because of the Red Terror and the Civil War. Vladimir applied for Trinity college at Cambridge University and chose foreign languages as his specialty. The two foreign languages were French (medieval and modern) and Russian.

Another passion of his life from the very childhood was Lepidopterology. Nabokov collected, hunted and described butterflies. His first serious study on the Crimean butterflies, written in English, was published in “The Etimologist” magazine on 1920.

Later on Nabokov liked to give himself out for lepidopterologist whose hobby was literature, but it was just one of his typical tricks and mystifications. He spent most of his enthusiasm on fiction.

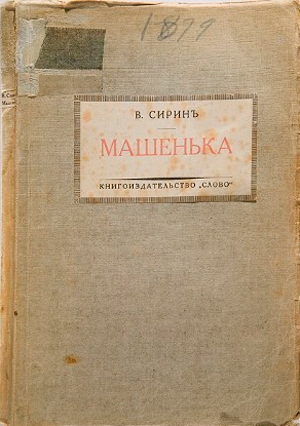

His first Russian literary publications, signed with pseudonym Syrin (the name of the mythological paradise bird), were printed by emigrant press (“Mashenka”, “The Defence”). Some short stories and lyrical poems where he depicted the drama and tragedy of the Russian refugees, the downfall of their first hopes and their despair (an emigrant chess-player Luzhin in “The Defence” committed a suicide by jumping out of the window) were accepted with understanding by readers. One of them was Ivan Bunin, the Noble Prize winner for literature and one of Nabokov’s authorities of that time.

His first Russian literary publications, signed with pseudonym Syrin (the name of the mythological paradise bird), were printed by emigrant press (“Mashenka”, “The Defence”). Some short stories and lyrical poems where he depicted the drama and tragedy of the Russian refugees, the downfall of their first hopes and their despair (an emigrant chess-player Luzhin in “The Defence” committed a suicide by jumping out of the window) were accepted with understanding by readers. One of them was Ivan Bunin, the Noble Prize winner for literature and one of Nabokov’s authorities of that time.

However, the young writer was far from following standards of the old realistic school. He was too complicated and ambitious for such a primitive task. Being a contemporary of the proletariat revolution and the bloody communist dictatorship, he hated any kind of primitivism and philistinism.

The next novels – “The Despair”, “The Lantern in the Dark” and “The Invitation to Beheading”, written in an anti-realistic, hard-modernist language, sometimes close to Kafkian absurdity, expressed not only his own existential cry but also a programmatic challenge to the cruelty of the communist dictatorship.

Dostoevsky noticed once that all Russian Literature went out of Gogol’s “Overcoat”. I should say that Nabokov came out of Gogol’s “Nose”. And when he stood up, everybody could see “The Diaries of a Madman” in his hands, opened on the last page.

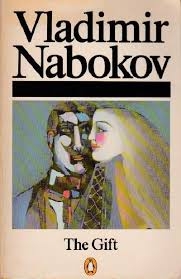

During that time the best of Nabokov’s novels was born. It was “The Gift”. It is very specific. There is no ordinary plot in the book. Formally, it is a life and carrier story of a Russian writer Godunov-Cherdyntsev and his love Zina Mortz. But the real heroine of the novel is not Zina. It is the Russian Literature. Modernist Language and the structure of “The Gift” which let Nabokov show the lustre and the darkness of our cultural heritage: from Pushkin to “the five poets” with names, beginning with “B”: Balmont, Bunin, Beliy, Blok and Bulgakov – the five senses of the new Russian poetry.

“The Gift” ’s author doesn’t say many words about his favorite writers in a direct way. You just see their reflections or allusions to their aesthetics, feel their invisible breathing. At the same time he dedicates the whole chapter 4 to the biography of Nikolai Chernyshevskiy, a famous revolutionary-populist (narodnik) and a spiritual father in the person of Lenin that becomes the negative center of the novel. Nabokov follows the example of Dostoevskiy’s “Demons” and gives a caricature portrait of the revolutionary, but he makes it in a different manner. Not to be boring, Nabokov retells the Cherdyntsev’s utilitarian and socially limited ideas in the black ironic verse.

“The Gift” ’s author doesn’t say many words about his favorite writers in a direct way. You just see their reflections or allusions to their aesthetics, feel their invisible breathing. At the same time he dedicates the whole chapter 4 to the biography of Nikolai Chernyshevskiy, a famous revolutionary-populist (narodnik) and a spiritual father in the person of Lenin that becomes the negative center of the novel. Nabokov follows the example of Dostoevskiy’s “Demons” and gives a caricature portrait of the revolutionary, but he makes it in a different manner. Not to be boring, Nabokov retells the Cherdyntsev’s utilitarian and socially limited ideas in the black ironic verse.

“…No great intelligence is needed to distinguish a connection between the teaching materialism, regarding inborn tendency to good; equality of man’s capacities – capacities that generally are termed mental; the great influence exterior circumstances have on a man; omnipotent of experience; sway of habit and upbringing; the extreme importance of industry; the moral right to pleasure and communism”.

In opposition to this blind social reductionism, Nabokov puts a pure aesthetic contemplation of the life mystery which we find in Godunov-Cherdyntsev’s poems:

One night between sunset and river

On the old bridge we stood, you and I,

“Will you ever forget it”, I queried,

“That particular swift that went by?”

And you answered so earnestly: “Never!”

And what sobs made us suddenly shiver

What story life emitted in flight

Till we die, till tomorrow, for ever,

You and I on the old bridge one night.

To any kind of negativism and foolish optimism, especially political demagogy with its promising “social progress”, “happy future”, he sets off his clear anti-equalizing pessimistic credo: “An oak is a tree, a rose is a flower, a deer is an animal, a sparrow is a bird. Russia is our Fatherland, death is inevitable”.

“The Gift” was received with cold indifference by the immigrant community. The Orthodox people couldn’t accept Nabokov’s antichristian philosophy, the left wing – his anti-socialist and anti-populist views, the bourgeois (in the Flaubertian sense) couldn’t accept his unusual Avant-Guard language. And, of course, it was impossible even to dream about some Russian readers in his Fatherland. All Nabokov’s works were absolutely banned by the Soviet regime.

This kind of reaction was not unexpected by the author. He was proud of his forced solitude:

Thank you, my land for your remotest,

Most cruel mist my thanks are due.

By you possessed, by you unnoticed

Unto myself I speak of you.

“The Gift” was the best Vladimir Nabokov’s novel, written by him in the native language. It was the top of the whole Russian period of his creative work. When the conclusive chapter of the book was completed in 1937 in France, he and his family – his wife Vera and his son Dmitry – moved from Europe to USA. There Nabokov had to find a job to earn his living. In Germany he taught many language classes. He taught Russian literature at Weleshy College and then from 1948 till 1959 he lectured on Russian and European Literature at Cornell University. And all that time he never stopped writing fiction.

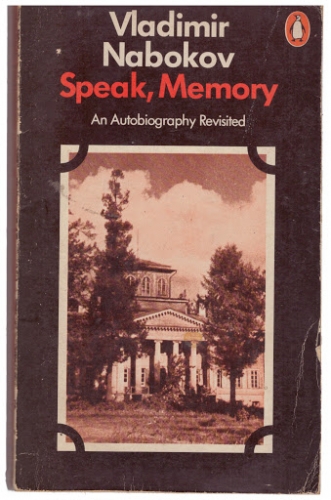

He finished the book of memories – its first title “Conclusive Evidence” (1951) – later changed into “Speak, Memory” by the author -, where he described in a pure classic manner his happy childhood in a family village Rozhdestveno near St. Petersburgh, portrayed with infinite tender his parents and represented the general life atmosphere of a good old pre-revolutionary Russia.

He finished the book of memories – its first title “Conclusive Evidence” (1951) – later changed into “Speak, Memory” by the author -, where he described in a pure classic manner his happy childhood in a family village Rozhdestveno near St. Petersburgh, portrayed with infinite tender his parents and represented the general life atmosphere of a good old pre-revolutionary Russia.

Very few people in America could appreciate that elegant nostalgic book. The next novels “The Real Life of Sebastian Knight» and «Bend Sinister” were easier and more understandable for a western reader but they were not noticed either. And Nabokov decided to create something totally different.

“Lolita, light of my life, fin of my loins. My sin, my soul, Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue, taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at thee, on the teeth. Lo-lee-ta!

She was Lo, plain Lo in the morning, standing from feet ten in one sock. She was Lola in slacks. She was Dolly at school. She was Dollores on the dotted line. But in my arms she was always Lolita”.

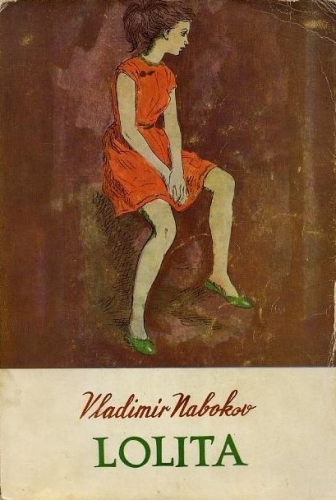

About 1955 he was writing the world famous, magic and sensational Lolita. It was a thrilling, intensely lyrical, sentimental story about the aging Humbert, Humbert’s doomed passion for a twelve-year-old nymphet, a sexually attractive young girl Dolores Haze.

“Wanted, wanted: Dolores Haze.

Hair: brown. Lips: scarlet.

Age: five thousand three hundred days.

Profession: None, or starlet”.

(…)

My car is limping, Dolores Haze,

And the last long lap is the hardest.

And I shall be dumped where the weed decays

And the rest of rust and stardust.

From the very beginning the book brought surprises to its author. Firstly, Nabokov could not find an editor in USA. When the novel was published by the “Olympic Press” in Paris, American critics fired a common volley at “Lolita”. One of them said that the author of the novel was “hypercivilized European debanching young American”, another classified the story as “pornographical”, the third called the book “anti-American” and the forth called it “anti-semitic”.

Humbert was at least three times mistaken for a Jew, and the pistol of his rival Guilty was a German one.

Nabokov tried to defend himself. He said that “Lolita” couldn’t be considered as anti-American. While composing the story, he tried to be an American writer. What one should bear in mind he was not a realistic author, he wrote fiction. It had taken Nabokov some forty years to invent Russia and Western Europe. And at that moment he faced the task of inventing America. He didn’t like Humbert Humbert. Indeed that character was not an American citizen, he was a foreigner and an anarchist. Nabokov disagreed with him in many ways, besides, nymphets like his, disagreed, for example, with Freid or Marx.

Nabokov tried to defend himself. He said that “Lolita” couldn’t be considered as anti-American. While composing the story, he tried to be an American writer. What one should bear in mind he was not a realistic author, he wrote fiction. It had taken Nabokov some forty years to invent Russia and Western Europe. And at that moment he faced the task of inventing America. He didn’t like Humbert Humbert. Indeed that character was not an American citizen, he was a foreigner and an anarchist. Nabokov disagreed with him in many ways, besides, nymphets like his, disagreed, for example, with Freid or Marx.

He was not understood and pled guilty. After an enormous scandal round “Lolita” Nabokov lost his job at Cornell University. After that final knock-out which in fact became the beginning of Nabokov’s world glory, the writer could devote all his time to the literary work. He published a poem “Pale Fire” of nine hundred ninety-nine lines, divided into four cantos with a long fantastic commentary, a novel “Pnin” about an emigrant university lecturer like him. Among other fiction, there was a novel “Ada or Azdor: a Family Chronicle”, some books and short stories, plays and a screen-play for his “Lolita”, ordered by Stanly Kubrik.

And let’s remember that Vladimir Nabokov was a brilliant translator and an expert in the world literature. The most important creation in this field was Pushkin’s “Eugen Onegyn”, published by Bollinger Foundation in four volumes with huge commentary in every one. He also made the English translation of “The Song of Igor’s Campaign”, a famous Medieval tale, Lermontov’s “Hero of our time” and some poems of the Russian classics. From English into Russian he retold “Alice’s Adventures in the Wonderland” by Luis Carrol (“Alisa v strane chudes”) and his memories (“Drugie Berega”).

Nabokov’s critical biography by Nikolai Gogol (a non-Christian interpretation of a Christian author were the first books, published in the Soviet Union. But his “Lectures on Russian Literature”, “Lecture on Literature” (on Western Europe), “Strong Opinions” where he collected some interviews, letters and articles were unknown until post-soviet times.

Nabokov’s critical biography by Nikolai Gogol (a non-Christian interpretation of a Christian author were the first books, published in the Soviet Union. But his “Lectures on Russian Literature”, “Lecture on Literature” (on Western Europe), “Strong Opinions” where he collected some interviews, letters and articles were unknown until post-soviet times.

“Why?” – you can ask. May be, because of his not very Russian American novels? I don’t think so. Many American writers have been translated and published in the USSR. By the way, Nabokov himself was quite clear about his country orientations, especially after he came back to Europe (Swirzerland) in 1961. Many time Nabokov said that he loved many things in America, where he had found good friends and readers, but he was not going to become a citizen of USA. He and his wife Vera were travelling from motel to motel, hunting butterflies. He had never had a house of his own. In one of his interviews, he said that he felt Russian and thought that his Russian works were a kind of a tribute to his Fatherland, as well as the English books on the Russian Literature.

Of course he realized that after living for so many years abroad he couldn’t remain unchangeable. He had to change. And it was a difficult kind of switch. Sometimes he said that his private tragedy should not be anybody’s concern, and he had to abandon his national idiom, his untrammeled rich and infinitely docile Russian tongue for a second-rate brand of English.

Nabokov was banned in the Soviet Union exactly for this nostalgia, because it was an invincible, indocile, unconquered love for the old, noble White Russia. He hated Lenin’s terrorist regime and any kind of communism. He despised the clumsy, trivial and melodramatic Soviet literature. And the Soviet writers couldn’t forgive it to him. Those literary bureaucrats couldn’t excuse neither his genius, nor his devine language which was dangerous like sunshine for the night shadows.

Vladimir Nabokov is coming back home. His dreams became true. Hundreds of underground copies of his best Russian novels. Nabokov’s books are on sale in St. Petersburgh and Moscow. Luzhin, Godunov-Cherdyntsev, Pnin and others live souls moor to “Drugie Berega”

Speaking on his memories, I would like to cite the concluding lines:

“To my love I will not say “Good-bye”.

I will carry it with me for ever.

And remember, please, “Never say never”

Till we live, till we honestly die”.

Pavel Toulaev, Utica College, N.Y., 1994

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Dans Lolita, ni femme ni culture. Seule une gamine de douze ans et l’Amérique des motels qui défile le long des routes. L’histoire en elle-même et le scandale qu’elle suscita n’apparaissent finalement que comme secondaires si l’on songe que le roman existait déjà en substance quinze ans plus tôt, sous le titre de L’Enchanteur, que Nabokov n’avait pas publié mais dont il reprend de très près la trame. Dans les deux œuvres, l’auteur insiste sur le caractère déterminant de la mère de la fillette, tantôt gravement malade et inspirant la pitié, tantôt vulgaire et ignare, suscitant le dégoût du narrateur autant que celui du lecteur. Lorsqu’il paraît, le roman reçoit de manière immédiate et étonnamment évidente le qualificatif de « littérature américaine ». En réalité, il s’agit là de bien davantage qu’un simple symbole, puisque c’est l’achèvement du détachement absolu des personnages de leurs origines culturelles, la rupture définitive avec la Russie amoureusement méprisée ou douloureusement regrettée et paradoxalement, dans l’évolution du style de Nabokov, du point culminant où les personnages, pourtant sans réelles profondeur et texture historiques, se donnent à voir dans leur plus complexe richesse. « Je suis le chien fidèle de la nature. Pourquoi alors ce sentiment d’horreur dont je ne puis me défaire ? », s’interroge Humbert Humbert, incapable d’aimer les femmes, mais torturé par l’amour d’une fillette.

Dans Lolita, ni femme ni culture. Seule une gamine de douze ans et l’Amérique des motels qui défile le long des routes. L’histoire en elle-même et le scandale qu’elle suscita n’apparaissent finalement que comme secondaires si l’on songe que le roman existait déjà en substance quinze ans plus tôt, sous le titre de L’Enchanteur, que Nabokov n’avait pas publié mais dont il reprend de très près la trame. Dans les deux œuvres, l’auteur insiste sur le caractère déterminant de la mère de la fillette, tantôt gravement malade et inspirant la pitié, tantôt vulgaire et ignare, suscitant le dégoût du narrateur autant que celui du lecteur. Lorsqu’il paraît, le roman reçoit de manière immédiate et étonnamment évidente le qualificatif de « littérature américaine ». En réalité, il s’agit là de bien davantage qu’un simple symbole, puisque c’est l’achèvement du détachement absolu des personnages de leurs origines culturelles, la rupture définitive avec la Russie amoureusement méprisée ou douloureusement regrettée et paradoxalement, dans l’évolution du style de Nabokov, du point culminant où les personnages, pourtant sans réelles profondeur et texture historiques, se donnent à voir dans leur plus complexe richesse. « Je suis le chien fidèle de la nature. Pourquoi alors ce sentiment d’horreur dont je ne puis me défaire ? », s’interroge Humbert Humbert, incapable d’aimer les femmes, mais torturé par l’amour d’une fillette.