Revoluçao Conservadora, forma catolica e "ordo aeternus" romano

A Revolução Conservadora não é somente uma continuação da «Deutsche Ideologie» romântica ou uma reactualização das tomadas de posição anti-cristãs e helenistas de Hegel (anos 1790-99) ou uma extensão do prussianismo laico e militar, mas tem também o seu lado católico romano. Nos círculos católicos, num Carl Schmitt por exemplo, como nos seus discípulos flamengos, liderados pela personalidade de Victor Leemans, uma variante da Revolução Conservadora incrusta-se no pensamento católico, como sublinha justamente um católico de esquerda, original e verdadeiramente inconformista, o Prof. Richard Faber de Berlim. Para Faber, as variantes católicas da RC renovam não com um Hegel helenista ou um prussianismo militar, mas com o ideal de Novalis, exprimido em Europa oder die Christenheit: este ideal é aquele do organon medieval, onde, pensam os católicos, se estabeleceu uma verdadeira ecúmena europeia, formando uma comunidade orgânica, solidificada pela religião.

Depois do retrocesso e da desaparição progressiva deste organon vivemos um apocalipse, que se vai acelerando, depois da Reforma, a Revolução francesa e a catástrofe europeia de 1914. Desde a revolução bolchevique de 1917, a Europa, dizem estes católicos conservadores alemães, austríacos e flamengos, vive uma Dauerkatastrophe. A vitória francesa é uma vitória da franco-maçonaria, repetem. 1917 significa a destruição do último reduto conservador eslavo, no qual haviam apostado todos os conservadores europeus desde Donoso Cortés( que era por vezes muito pessimista, sobretudo quando lia Bakunine). Os prussianos haviam sempre confiado na aliança russa. Os católicos alemães e austríacos também, mas com a esperança de converter os russos à fé romana. Enfim, o abatimento definitivo dos “estados” sociais, inspirados na época medieval e na idade barroca (instalados ou reinstalados pela Contra-Reforma) mergulha os conservadores católicos no desespero. Helena von Nostitz, amiga de Hugo von Hoffmannstahl, escreve «Wir sind am Ende, Österreich ist tot. Der Glanz, die Macht ist dahin» [« Estamos no fim, a Áustria está morta. O Esplendor e o Poder desapareceram»].

Num tal contexto, o fascismo italiano, contudo saído da extrema-esquerda intervencionista italiana, dos meios socialistas hostis à Áustria conservadora e católica, figura como uma reacção musculada da romanidade católica contra o desafio que lança o comunismo a leste. O fascismo de Mussolini, sobretudo depois dos acordos de Latran, recapitula, aos olhos destes católicos austríacos, os valores latinos, virgilianos, católicos e romanos, mas adaptando-os aos imperativos da modernidade.

É aqui que as referências católicas ao discurso de Donoso Cortés aparecem em toda a sua ambiguidade: para o polemista espanhol a Rússia arriscava converter-se ao socialismo para varrer pela violência o liberalismo decadente, como teria conseguido se tivesse mantido a sua opção conservadora. Esta evocação da socialização da Rússia por Donoso Cortés permite a certos conservadores prussianos, como Moeller van den Bruck, simpatizar com o exército vermelho, para parar a Oeste os exércitos ao serviço do liberalismo maçónico ou da finança anglo-saxónica, ainda mais porque depois do tratado de Rapallo(1922), a Reichswehr e o novo exército vermelho cooperam. O reduto russo permanece intacto, mesmo se mudou de etiqueta ideológica.

Hugo von Hoffmannstahl, em Das Schriftum als geistiger Raum der Nation [As cartas como espaço espiritual da Nação] utiliza pela primeira vez na Alemanha o termo “Revolução Conservadora”, tomando assim o legado dos russos que o haviam precedido, Dostoievski e Yuri Samarine. Para ele a RC é um contra-movimento que se opõe a todas as convulsões espirituais desde o século XVI. Para Othmar Spann, a RC é uma Contra-Renascença. Quanto a Eugen Rosenstock( que é protestante), escreve: «Um vorwärts zu leben, müssen wir hinter die Glaubensspaltung zurückgreifen» [Para continuar a viver, seguindo em frente, devemos recorrer ao que havia antes da ruptura religiosa]. Para Leopold Ziegler (igualmente protestante) e Edgard Julius Jung (protestante), era preciso uma restitutio in integrum, um regresso à integralidade ecuménica europeia, Julius Evola teria dito: à Tradição. Eles queriam dizer por aquilo que os Estados não deviam mais opor-se uns aos outros mas ser reconduzidos num “conjunto potencializador”.

Se Moeller van den Bruck e Eugen Rosenstock actuam em clubes, como o Juni-Klub, o Herren-Klub ou em círculos que gravitam em torno da revista de sociologia, economia e politologia Die Tat, os que desejam manter uma ética católica e cuja fé religiosa subjuga todo o comportamento, reagrupam-se em “círculos” mais meditativos ou em ordens de conotação monástica. Richard Feber calcula que estas criações católicas, neo-católicas ou para-católicas, de “ordens”, se efectuaram a 4 níveis:

1)No círculo literário e poético agrupado em torno da personalidade de Stefan George, aspirando a um “novo Reich”, isto é, um “novo reino” ou um “novo éon”, mais do que a uma estrutura política comparável ao império dos Habsbourg ou ao dos Hohenzollern.

2)No “Eranos-Kreis”( Círculo Eranos) do filósofo místico Derleth, cujo pensamento se inscreve na tradição de Virgílio ou Hölderlin, colocando-se sob a insígnia de uma “Ordem do Christus- Imperator”.

3)Nos círculos de reflexão instalados em Maria Laach, na Renânia-Palatinado, onde se elaborava uma espécie de neo-catolicismo alemão sob a direcção do teólogo Peter Wust, comparável, em muitos aspectos, ao “Renouveau Catholique” de Maritain na França (que foi próximo, a dado momento, da Acção Francesa) e onde a fé se transmitia aos aprendizes particularmente por uma poesia derivada dos cânones e das temáticas estabelecidas pelo “Circulo” de Stefan George em Munique-Schwabing desde os anos 20.

4)Nos movimentos de juventude, mais ou menos confessionais ou religiosos, particularmente nas suas variantes “Bündisch”, bom número de responsáveis desejavam introduzir, por via das suas ligas ou das suas tropas, uma “teologia dos mistérios”.

As variantes católicas ou catolizantes, ou pós-católicas, preconizaram então um regresso à metafísica política, no sentido em que queriam uma restauração do “Ordo romanus”, “Ordem romana”, definida por Virgílio como “Ordo aeternus”, “ordem eterna”. Este catolicismo apelava à renovação com esse “Ordo aeternus” romano que, na sua essência, não era cristão mas a expressão duma paganização do catolicismo, explica-nos o cristão católico de esquerda Richard Faber, no sentido em que, neste apelo à restauração do “Ordo romanus/aeternus”, a continuidade católica não é já fundamentalmente uma continuidade cristã mas uma continuidade arcaica. Assim, a “forma católica” veicula, cristianizando-a (na superfície?), a forma imperial antiga de Roma, como assinalou igualmente Carl Schmitt em Römischer Katholizismus und politische Form (1923). Nessa obra, o politólogo e jurista alemão lança de alguma maneira um duplo apelo: à forma (que é essencialmente, na Europa, romana e católica, ou seja, universal enquanto imperial e não imediatamente enquanto cristã) e à Terra (esteio incontornável de toda a acção política), contra o economicismo volúvel e hiper-móvel, contra a ideologia sem esteio que é o bolchevismo, aliado objectivo do economicismo anglo-saxónico.

Para os proponentes deste catolicismo mais romano que cristão, para um jurista e constitucionalista como Schmitt, o anti-catolicismo saído da filosofia das Luzes e do positivismo cienticista( referências do liberalismo) rejeita de facto esta matriz imperial e romana, este primitivismo antigo e fecundo, e não o eudemonismo implícito do cristianismo. O objectivo desta romanidade e desta “imperialidade” virgiliana consiste no fundo, queixa-se Faber, que é um anti-fascista por vezes demasiado militante, em meter o catolicismo cristão entre parênteses para mergulhar directamente, sem mais nenhum derivativo, sem mais nenhuma pseudo-morfose (para utilizar um vocábulo spengleriano), no “Ordo aeternus”.

Na nossa óptica este discurso acaba ambíguo, porque há confusão permanente entre Europa e Ocidente. Com efeito, depois de 1945, o Ocidente, vasto receptáculo territorial oceânico-centrado, onde é sensato recompor o “Ordo romanus” para estes pensadores conservadores e católicos, torna-se a Euroamérica, o Atlantis: paradoxo difícil de resolver, porque como ligar os princípios “térreos” (Schmitt) e os da fluidez liberal, hiper-moderna e economicista da civilização “estado-unidense”?

Para outros, entre o Oriente bolchevizado e pós-ortodoxo e o Hiper-Ocidente fluido e ultra-materialista, deve erguer-se uma potência “térrea”, justamente instalada sobre o território matricial da “imperialidade” virgiliana e carolíngia, e esta potência é a Europa em gestação. Mas com a Alemanha vencida, impedida de exercer as suas funções imperiais pós-romanas uma translatio imperii (translação do império) deve operar-se em beneficio da França de De Gaulle, uma translação imperii ad Gallos, temática em voga no momento da reaproximação entre De Gaulle e Adenauer e mais pertinente ainda no momento em que Charles De Gaulle tenta, no curso dos anos 60, posicionar a França “contra os impérios”, ou seja, contra os “imperialismos”, veículos da fluidez mórbida da modernidade anti-política e antídotos para toda a forma de fixação estabilizante (NdT. Daqui presume-se uma distinção entre imperialismo e imperialidade, daí o uso dos dois conceitos).

Se Eric Voegelin tinha teorizado um conservantismo em que a ideologia derivava da noção de “Ordo romanus”, ele colocava o seu discurso filosófico-político ao serviço da NATO, esperando deste modo uma fusão entre os princípios “fluidos” e “térreos” (NdT. naturalmente esta dicotomia que o autor usa recorrentemente no texto é uma referência à tradicional oposição entre ordenamentos marítimos e terrestres) , o que é uma impossibilidade metafísica e prática. Se o tandem De Gaulle-Adenauer se referia também, sem dúvida, no topo, a um projecto derivado da noção de “Ordo aeternus”, colocava o seu discurso e as suas práticas, num primeiro momento (antes da viagem de De gaulle a Moscovo, à América Latina e antes da venda dos Mirage à Índia e do famosos discursos de Pnom-Penh e do Quebeque), ao serviço de uma Europa mutilada, hemiplégica, reduzida a um “rimland” atlântico vagamente alargado e sem profundidade estratégica. Com os últimos escritos de Thomas Molnar e de Franco Cardini, com a reconstituição geopolítica da Europa, este discurso sobre o “Ordo romanus et aeternus” pode por fim ser posto ao serviço de um grande espaço europeu, viável, capaz de se impor sob a cena internacional. E com as proposições de um russo como Vladimir Wiedemann-Guzman, que percepciona a reorganização do conjunto euro-asiático numa “imperialidade” bicéfala, germânica e russa, a expansão grande-continental está em curso, pelo menos no plano teórico. E para terminar, parafraseando De Gaulle: A estrutura administrativa acompanhá-la-á?

Robert Steuckers

Archives de Synergies Européennes - 1992

Archives de Synergies Européennes - 1992

Il y a maintenant cent ans, Ernst von Salomon naissait le 25 septembre 1902 à Kiel, alors en Prusse. Ce qui l'a marqué, c'est l'attitude prussienne, la rigueur envers soi-même, les vertus prussiennes, sans oublier le "socialisme prussien". Toute sa vie a tourné autour de cet esprit d'État de la Prusse ; c'était son père nourricier, son mythe, son but, et surtout son substitut à l'identité allemande détruite. La patrie ne signifiait rien pour lui, l'identité tout. Outre le foyer familial, c'est surtout son éducation dans le corps préparatoire des cadets royaux prussiens qui y a contribué. C'est là que les cadets ont appris les vertus de l'État, jusqu'à ce qu'ils soient jetés dans la guerre civile qui faisait rage fin 1918 par un décret des dirigeants alliés en Allemagne.

Il y a maintenant cent ans, Ernst von Salomon naissait le 25 septembre 1902 à Kiel, alors en Prusse. Ce qui l'a marqué, c'est l'attitude prussienne, la rigueur envers soi-même, les vertus prussiennes, sans oublier le "socialisme prussien". Toute sa vie a tourné autour de cet esprit d'État de la Prusse ; c'était son père nourricier, son mythe, son but, et surtout son substitut à l'identité allemande détruite. La patrie ne signifiait rien pour lui, l'identité tout. Outre le foyer familial, c'est surtout son éducation dans le corps préparatoire des cadets royaux prussiens qui y a contribué. C'est là que les cadets ont appris les vertus de l'État, jusqu'à ce qu'ils soient jetés dans la guerre civile qui faisait rage fin 1918 par un décret des dirigeants alliés en Allemagne. Il déserta et se rendit dans les pays baltes, où les troupes allemandes progressaient pour la première fois depuis la guerre. Il pensait trouver l'Allemagne sur le front, mais ce front n'était pas allemand: les troupes allemandes se battaient contre les bolcheviks pour le compte des Anglais afin d'assurer le statu quo d'après-guerre. Ils ne l'ont compris que lorsque les Anglais sont tombés dans leur piège et que le gouvernement allemand les a abandonnés et ostracisés. C'est alors que leur idéalisme s'est exacerbé jusqu'à l'excès. La reconnaissance de la paix de Versailles les a libérés intérieurement. Ils se crurent les derniers Allemands, devinrent irréguliers, se battirent et tuèrent sans idée et sans but, jusqu'à ce qu'ils soient obligés de se retirer dans le Reich, vaincus et amers, au tournant des années 1919 et 1920. Mais là, l'ingratitude, la méfiance, la haine idéologique et la dissolution les attendaient. C'est ainsi qu'ils se mirent à la disposition de Kapp, qui tenta un coup d'État sans préparation et totalement insuffisant. Lorsque, suite à l'échec inévitable de ce putsch, les syndicats tentèrent à nouveau de prendre le pouvoir en Allemagne sous le slogan communiste et internationaliste, le lieutenant von Salomon se laissa à nouveau abuser comme volontaire temporaire dans les rangs de la Reichswehr qui "nettoyait" la Ruhr.

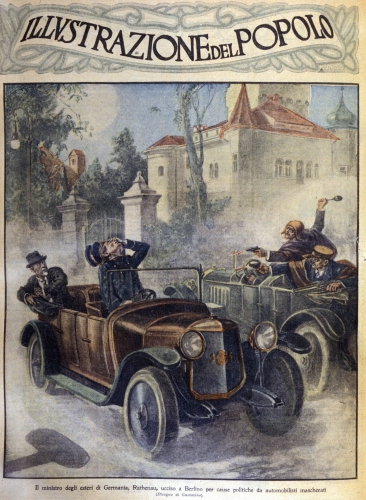

Il déserta et se rendit dans les pays baltes, où les troupes allemandes progressaient pour la première fois depuis la guerre. Il pensait trouver l'Allemagne sur le front, mais ce front n'était pas allemand: les troupes allemandes se battaient contre les bolcheviks pour le compte des Anglais afin d'assurer le statu quo d'après-guerre. Ils ne l'ont compris que lorsque les Anglais sont tombés dans leur piège et que le gouvernement allemand les a abandonnés et ostracisés. C'est alors que leur idéalisme s'est exacerbé jusqu'à l'excès. La reconnaissance de la paix de Versailles les a libérés intérieurement. Ils se crurent les derniers Allemands, devinrent irréguliers, se battirent et tuèrent sans idée et sans but, jusqu'à ce qu'ils soient obligés de se retirer dans le Reich, vaincus et amers, au tournant des années 1919 et 1920. Mais là, l'ingratitude, la méfiance, la haine idéologique et la dissolution les attendaient. C'est ainsi qu'ils se mirent à la disposition de Kapp, qui tenta un coup d'État sans préparation et totalement insuffisant. Lorsque, suite à l'échec inévitable de ce putsch, les syndicats tentèrent à nouveau de prendre le pouvoir en Allemagne sous le slogan communiste et internationaliste, le lieutenant von Salomon se laissa à nouveau abuser comme volontaire temporaire dans les rangs de la Reichswehr qui "nettoyait" la Ruhr. Leurs actions ont culminé le 24 juin 1922 avec l'assassinat de Walther Rathenau. Ils avaient cru reconnaître dans le juif Rathenau, qui se trouvait en fait "dès le départ du côté de ses adversaires" (Harry Graf Kessler), et ils étaient soutenus en cela par des politiciens de parti sans scrupules et pour la plupart germanophiles, le seul représentant doué du libéralisme qui pourrait apporter la stabilité à la République et en abuser au détriment des Allemands et au profit de l'impérialisme économique international. Mais en fait, ils ne faisaient que se convaincre de quelque chose : "C'était la démocratie, c'était la justification politique que nous cherchions. Nous en cherchions une - il y avait, par exemple, une politique d'accomplissement. Pour nous, la guerre n'était pas finie, pour nous, la révolution n'était pas terminée".

Leurs actions ont culminé le 24 juin 1922 avec l'assassinat de Walther Rathenau. Ils avaient cru reconnaître dans le juif Rathenau, qui se trouvait en fait "dès le départ du côté de ses adversaires" (Harry Graf Kessler), et ils étaient soutenus en cela par des politiciens de parti sans scrupules et pour la plupart germanophiles, le seul représentant doué du libéralisme qui pourrait apporter la stabilité à la République et en abuser au détriment des Allemands et au profit de l'impérialisme économique international. Mais en fait, ils ne faisaient que se convaincre de quelque chose : "C'était la démocratie, c'était la justification politique que nous cherchions. Nous en cherchions une - il y avait, par exemple, une politique d'accomplissement. Pour nous, la guerre n'était pas finie, pour nous, la révolution n'était pas terminée".

La deuxième partie de cette trilogie d'après-guerre, La Ville, presque illisible et pourtant d'un intérêt explosif, a été écrite en 1932 : "La Ville était une tentative, un inventaire, un exercice de type littéraire, dans lequel je me suis intéressé à certains problèmes d'écriture très particuliers. La matière est certes intéressante, mais sans engagement pour moi ; elle ne m'a servi qu'à aiguiser toutes les questions". Et la troisième partie, la conclusion de son "Nouveau nationalisme", qui devait être en même temps sa plus belle œuvre littéraire, Les Cadets, avait été écrite dans l'atmosphère si différente de Vienne. C'est là qu'au cours de l'hiver 1932-1933, invité par Othmar Spann, von Salomon découvrit l'austro-universalisme de ce dernier, et n'en devint que plus conscient de ses origines prussiennes et de son propre nominalisme: "Tous les grands mouvements du monde, le christianisme comme l'humanisme, comme le marxisme, sont atteints d'une sorte de maladie, une maladie divine, la peste sublime de la prétention à la totalité. C'est ce qui rend les choses si simples pour celui qui veut se confesser et si difficiles pour celui qui les regarde. Moi, je ne suis pas un confesseur, je suis un observateur passionné. C'est ainsi que je ne suis pas devenu national-socialiste, et c'est ainsi que j'ai dû me séparer d'Othmar Spann".

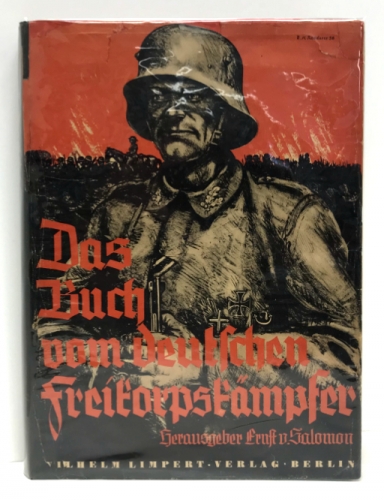

La deuxième partie de cette trilogie d'après-guerre, La Ville, presque illisible et pourtant d'un intérêt explosif, a été écrite en 1932 : "La Ville était une tentative, un inventaire, un exercice de type littéraire, dans lequel je me suis intéressé à certains problèmes d'écriture très particuliers. La matière est certes intéressante, mais sans engagement pour moi ; elle ne m'a servi qu'à aiguiser toutes les questions". Et la troisième partie, la conclusion de son "Nouveau nationalisme", qui devait être en même temps sa plus belle œuvre littéraire, Les Cadets, avait été écrite dans l'atmosphère si différente de Vienne. C'est là qu'au cours de l'hiver 1932-1933, invité par Othmar Spann, von Salomon découvrit l'austro-universalisme de ce dernier, et n'en devint que plus conscient de ses origines prussiennes et de son propre nominalisme: "Tous les grands mouvements du monde, le christianisme comme l'humanisme, comme le marxisme, sont atteints d'une sorte de maladie, une maladie divine, la peste sublime de la prétention à la totalité. C'est ce qui rend les choses si simples pour celui qui veut se confesser et si difficiles pour celui qui les regarde. Moi, je ne suis pas un confesseur, je suis un observateur passionné. C'est ainsi que je ne suis pas devenu national-socialiste, et c'est ainsi que j'ai dû me séparer d'Othmar Spann". De retour à Berlin, où le NSDAP s'efforçait de trouver un terrain d'entente entre lui-même et les corps francs, la préoccupation première de von Salomon était à nouveau de contrer les falsifications dans l'historiographie de l'après-guerre. C'est ainsi que ses deux livres Nahe Geschichte (Histoire proche) et le monumental Buch vom deutschen Freikorpskämpfer (Livre du combattant allemand des Corps Francs) ont vu le jour en tant que correctifs de la déformation de l'histoire nationale-socialiste. Cependant, lorsque de sérieuses difficultés surgirent avec le NSDAP, il se retira de tous les cercles compromettants, y compris du cercle de Harro Schulze-Boysen, par égard pour sa compagne juive qu'il fit passer pour son épouse pendant le Troisième Reich, et "émigra" à la UFA en tant que scénariste.

De retour à Berlin, où le NSDAP s'efforçait de trouver un terrain d'entente entre lui-même et les corps francs, la préoccupation première de von Salomon était à nouveau de contrer les falsifications dans l'historiographie de l'après-guerre. C'est ainsi que ses deux livres Nahe Geschichte (Histoire proche) et le monumental Buch vom deutschen Freikorpskämpfer (Livre du combattant allemand des Corps Francs) ont vu le jour en tant que correctifs de la déformation de l'histoire nationale-socialiste. Cependant, lorsque de sérieuses difficultés surgirent avec le NSDAP, il se retira de tous les cercles compromettants, y compris du cercle de Harro Schulze-Boysen, par égard pour sa compagne juive qu'il fit passer pour son épouse pendant le Troisième Reich, et "émigra" à la UFA en tant que scénariste.

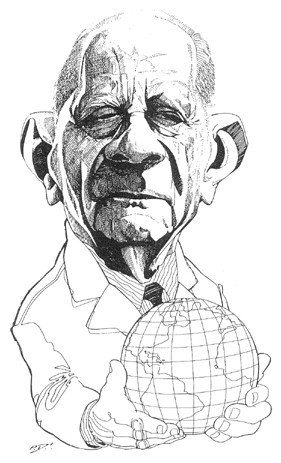

The most important critique of Spengler among the Revolutionary Conservative intellectuals was that made by Arthur Moeller van den Bruck.[6] Moeller agreed with certain basic ideas in Spengler’s work, including the division between Kultur and Zivilisation, with the idea of the decline of the Western Culture, and with his concept of socialism, which Moeller had already expressed in an earlier and somewhat different form in Der Preussische Stil (“The Prussian Style,” 1916).[7] However, Moeller resolutely rejected Spengler’s deterministic and fatalistic view of history, as well as the notion of destined culture cycles. Moeller asserted that history was essentially unpredictable and unfixed: “There is always a beginning (…) History is the story of that which is not calculated.”[8] Furthermore, he argued that history should not be seen as a “circle” (in Spengler’s manner) but rather a “spiral,” and a nation in decline could actually reverse its decline if certain psychological changes and events could take place within it.[9]

The most important critique of Spengler among the Revolutionary Conservative intellectuals was that made by Arthur Moeller van den Bruck.[6] Moeller agreed with certain basic ideas in Spengler’s work, including the division between Kultur and Zivilisation, with the idea of the decline of the Western Culture, and with his concept of socialism, which Moeller had already expressed in an earlier and somewhat different form in Der Preussische Stil (“The Prussian Style,” 1916).[7] However, Moeller resolutely rejected Spengler’s deterministic and fatalistic view of history, as well as the notion of destined culture cycles. Moeller asserted that history was essentially unpredictable and unfixed: “There is always a beginning (…) History is the story of that which is not calculated.”[8] Furthermore, he argued that history should not be seen as a “circle” (in Spengler’s manner) but rather a “spiral,” and a nation in decline could actually reverse its decline if certain psychological changes and events could take place within it.[9]

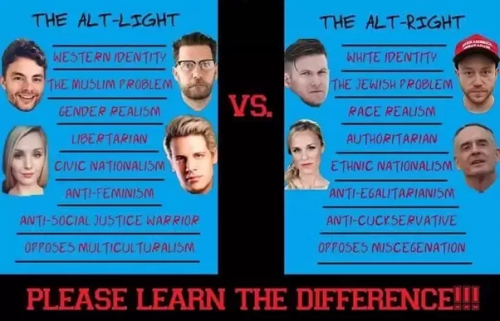

The Alt-Right broadly defined would be anything on the Right that is in opposition to the neocon-led Republican alliance. This could include everything from many Donald Trump voters in the mainstream, to various tendencies that have been given such labels as the “alt-lite,” the new right, the radical right, the populist right, the dark enlightenment, the identitarians, the neo-reactionaries, the manosphere (or “men’s right advocates”), civic nationalists, economic nationalists, Southern nationalists, white nationalists, paleoconservatives, right-wing anarchists, right-leaning libertarians (or “paleolibertarians”), right-wing socialists, neo-monarchists, tendencies among Catholic or Eastern Orthodox traditionalists, neo-pagans, Satanists, adherents of the European New Right, Duginists, Eurasianists, National-Bolsheviks, conspiracy theorists, and, of course, actually self-identified Fascists and National Socialists. I have encountered all of these perspectives and others in Alt-Right circles.

The Alt-Right broadly defined would be anything on the Right that is in opposition to the neocon-led Republican alliance. This could include everything from many Donald Trump voters in the mainstream, to various tendencies that have been given such labels as the “alt-lite,” the new right, the radical right, the populist right, the dark enlightenment, the identitarians, the neo-reactionaries, the manosphere (or “men’s right advocates”), civic nationalists, economic nationalists, Southern nationalists, white nationalists, paleoconservatives, right-wing anarchists, right-leaning libertarians (or “paleolibertarians”), right-wing socialists, neo-monarchists, tendencies among Catholic or Eastern Orthodox traditionalists, neo-pagans, Satanists, adherents of the European New Right, Duginists, Eurasianists, National-Bolsheviks, conspiracy theorists, and, of course, actually self-identified Fascists and National Socialists. I have encountered all of these perspectives and others in Alt-Right circles.