mercredi, 14 janvier 2015

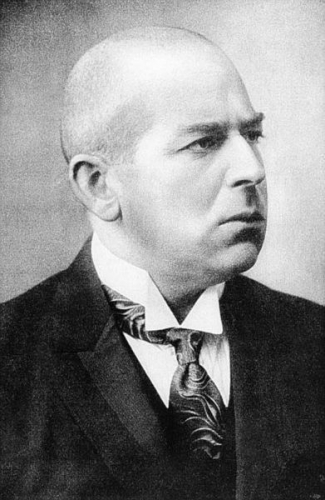

Oswald Spengler & the Faustian Soul of the West

Oswald Spengler & the Faustian Soul of the West,

Part 1

By Ricardo Duchesne

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

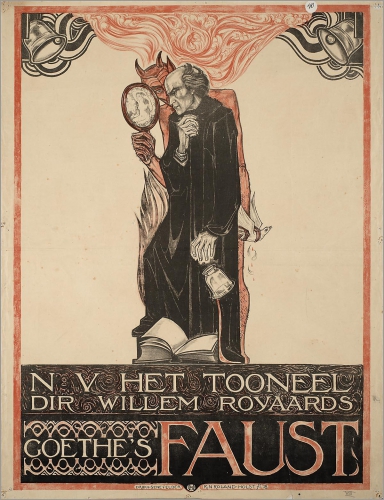

If I had to choose one word to identify the uniqueness of the West it would be “Faustian.” This is the word Oswald Spengler used to designate the “soul” of the West. He believed that Western civilization was driven by an unusually dynamic and expansive psyche. The “prime-symbol” of this Faustian soul was “pure and limitless space.” This soul had a “tendency towards the infinite,” a tendency most acutely expressed in modern mathematics.

The “infinite continuum,” the exponential logarithm and “its dissociation from all connexion with magnitude” and transference to a “transcendent relational world” were some of the words Spengler used to describe Western mathematics. But he also wrote of the “bodiless music” of the Western composer, “in which harmony and polyphony bring him to images of utter ‘beyondness’ that transcend all possibilities of visual definition,” and, before the modern era, of the Gothic “form-feeling” of “pure, imperceptible, unlimited space” (Decline of the West, Vol.1, Form and Actuality [Alfred Knopf, 1923] 1988: 53-90).

This soul type was first visible, according to Spengler, in medieval Europe, starting with Romanesque art, but particularly in the “spaciousness of Gothic cathedrals,” “the heroes of the Grail and Arthurian and Siegfried sagas, ever roaming in the infinite, and the Crusades,” including “the Hohenstaufen in Sicily, the Hansa in the Baltic, the Teutonic Knights in the Slavonic East, [and later] the Spaniards in America, [and] the Portuguese in the East Indies.” Spengler thus viewed the West as a strikingly vibrant culture driven by a type of personality overflowing with expansive impulses, “intellectual will to power.” “Fighting,” “progressing,” “overcoming of resistances,” battling “against what is near, tangible and easy” – these were some of the terms Spengler used to describe this soul (Decline of the West: 183-216).

A variety of words have been used to describe or identify the peculiar history of the West: “individualist,” “rationalist,” “imperialist,” “secularist,” “restless,” and “racist.” Spengler’s term “Faustian,” it seems to me, best captures the persistent, and far greater, originality of the West since ancient times in all the intellectual, artistic, and heroic spheres of life. But many today don’t read Spengler; there are no indications, in fact, that the foremost experts on the so-called “rise of the West” have even read any of his works.

The current academic consensus has reduced the uniqueness of the West to when this civilization “first” became industrial. This consensus believes that the West “diverged” from other agrarian civilizations only when it developed steam engines capable of using inorganic sources of energy. Prior to the industrial revolution, we are made to believe, there were “surprising similarities” between Europe and Asia. Both multiculturalist and Eurocentric historians tend to frame the “the rise of the West” or the “great divergence” in these economic/technological terms. David Landes, Kenneth Pomeranz, Bin Wong, Joel Mokyr, Jack Goldstone, E. L. Jones, and Peer Vries all single out the Industrial Revolution of 1750/1830 as the transformation which signaled a whole new pattern of evolution for the West (or England in the first instance). It matters little how far back in time these academics trace this Revolution, or how much weight they assign to preceding developments such as the Scientific Revolution or the slave trade, their emphasis is on the “divergence” generated by the arrival of mechanized industry and self-sustained increases in productivity sometime after 1750.

But I believe that the Industrial Revolution, including developments leading to this Revolution, barely capture what was unique about Western culture. I am obviously aware that other cultures were unique in having their own customs, languages, beliefs and historical experiences. My claim is that the West was uniquely exceptional in exhibiting in a continuous way the greatest degree of creativity, novelties, and expansionary dynamic. I trace the uniqueness of the West back to the aristocratic warlike culture of Indo-European speakers [2] as early as the fourth millennium. The aristocratic libertarian culture of Indo-European speakers was already unique and quite innovative in initiating the most mobile way of life in prehistoric times [3] starting with the domestication and riding of horses and the invention of chariot warfare. So were the ancient Greeks in their discovery of logos and its link with the order of the world, dialectical reason, the invention of prose, tragedy, citizen politics, and face-to-face infantry battle.

But I believe that the Industrial Revolution, including developments leading to this Revolution, barely capture what was unique about Western culture. I am obviously aware that other cultures were unique in having their own customs, languages, beliefs and historical experiences. My claim is that the West was uniquely exceptional in exhibiting in a continuous way the greatest degree of creativity, novelties, and expansionary dynamic. I trace the uniqueness of the West back to the aristocratic warlike culture of Indo-European speakers [2] as early as the fourth millennium. The aristocratic libertarian culture of Indo-European speakers was already unique and quite innovative in initiating the most mobile way of life in prehistoric times [3] starting with the domestication and riding of horses and the invention of chariot warfare. So were the ancient Greeks in their discovery of logos and its link with the order of the world, dialectical reason, the invention of prose, tragedy, citizen politics, and face-to-face infantry battle.

The Roman creation of a secular system of republican governance anchored on autonomous principles of judicial reasoning was in and of itself unique. The incessant wars and conquests of the Roman legions, together with their many war-making novelties and engineering skills, were one of the most vital illustrations of spatial expansionism [4] in history. The fusion of Christianity and the Greco-Roman intellectual and administrative heritage, coupled with the cultivation of the first rational theology in history [5], Catholicism, were a unique phenomenon. The medieval invention of universities [6] — in which a secular education could flourish and even articles of faith were open to criticism and rational analysis in an effort to arrive at the truth — was exceptional. The list of epoch making transformation in Europe is endless, the Renaissance, the Age of Discovery, the Scientific Revolution(s), the Military Revolution(s), the Cartographic Revolution, the Spanish Golden Age, the Printing Revolution, the Enlightenment, the Romantic Era, the German Philosophical Revolutions from Kant to Hegel to Nietzsche to Heidegger.

Limitations in Charles Murray’s Measurement of the Accomplishments of Western civilization

Some may wonder how can one make a comparative judgment about the accomplishments of civilizations without some objective criteria or standard of measurement. There is a book by Charles Murray published in 2003, Human Accomplishment: The Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts and Sciences, 800 B.C. to 1950 [7], which systematically arranges “data that meet scientific standards of reliability and validity” for the purpose of evaluating the story of human accomplishments across cultures. It is the first effort to quantify “as facts” the accomplishments of individuals and countries across the world in the arts and sciences by calculating the amount of space allocated to these individuals in reference works, encyclopedias, and dictionaries. Charles Murray informs us that ninety-seven percent of accomplishment in the sciences occurred in Europe and North America from 800 BC to 1950. It also informs us that, in the Arts, Europe alone produced a far higher number of “significant figures” than the rest of the world combined. In music, “the lack of a tradition of named composers in non-Western civilization means that the Western total of 522 significant figures has no real competition at all” (p. 252-259).

Murray avoids a Eurocentric bias by creating separate compilations for each of “the giants” in the arts of the Arab world, China, India, and Japan, as well as of the “giants” of Europe. In this respect, Murray recognizes that one cannot apply one uniform standard of excellence for the diverse artistic traditions of the world. But he produces combined (worldwide) inventories of “the giants” for each of the natural sciences. Combined lists for the natural sciences are possible since world scientists themselves have come to accept the same methods and categories. The most striking feature of his list of “the giants” in the sciences (the top 20 in Astronomy, Physics, Biology, Medicine, Chemistry, Earth Sciences, and Mathematics) is that they are all (excepting one Japanese) Western (p. 84, 122-29).

What explanation does Murray offer for this remarkable “divergence” in human accomplishments? He argues that human accomplishment is determined by the degree to which cultures promote or discourage individual autonomy and purpose. Accomplishments have been “more common and more extensive in cultures where doing new things and acting autonomously [were] encouraged than in cultures [where they were] disapprove[d].” Human beings have also been “most magnificently productive and reached their highest cultural peaks in the times and places where humans have thought most deeply about their place in the universe and been most convinced they have one” (p. 394-99). The West was different in affording individuals greater autonomy and purpose.

One major limitation in Murray is that he attributes to Christianity this sense of purpose and place in the universe, unable to account for the incredible accomplishment of the pagan Greeks and Romans. It is also the case that Murray’s Human Accomplishment is a statistical assessment, an inventory of names, not an attempt to capture the historically dynamic character of Western individualism. His book leaves out all the dramatic transformations historians have identified with the West: Why did the voyages of global discovery “take place” in early modern Europe and not in China? Why did Newtonian mechanics elude other civilizations? Actually, no current historical work addresses all these transformations together. Countless books have been published on one or two major European transformations, but no scholar has tried to explain, or pose as a general question, the persistent creativity of Europeans from ancient to modern times across all the fields of human endeavor. The norm has been for specialists in one period or transformation to write about (or insist upon) the “radical” or “revolutionary” significance of the period or theme they happen to be experts on.

Missing is an understanding of the unparalleled degree to which the entire history of the West was filled with individuals persistently seeking “to transcend every optical limitation” (Decline of the West: 198). In comparative contrast to the history of India, China, Japan, Egypt, and the Americas, where artistic styles, political institutions and philosophical outlooks lasted for centuries, stands the “dynamic fertility of the Faustian with its ceaseless creation of new types and domains of form” (Decline of the West: 205). I can think of only three individuals, two philosophers of history and one historical sociologist, who have written in a wide-ranging way of:

- the “infinite drive,” “the irresistible trust” of the Occident,

- the “energetic, imperativistic, and dynamic” soul of the West, and

- the “rational restlessness” of the West

— Hegel, Spengler, and Weber.

Spengler is the one who overcomes in a keener way another flaw in Murray: his account of European distinctiveness is limited to the intellectual and artistic spheres. He pays no attention to accomplishments in warfare, exploration, and heroic leadership. His definition of accomplishment includes only peaceful individuals carrying scientific experiments and creating artistic works. Achievements come only in the form of “great books” and “great ideas.” In this respect, Human Accomplishment is akin to certain older-style Western Civ textbooks where the production of “Great Works” by “Great Men” in conditions of “Liberty” were the central themes. David Gress dubbed this type of historiography the “Grand Narrative [8]” (1998). By teaching Western history in terms of the realization of great ideas and works in the arts and sciences these texts “placed a burden of justification on the West” to explain how the reality of Western colonialism across the world, the higher degree of warfare among Europeans, the invention of far more destructive military weapons, the slave trade, and the unprecedented destruction of the civilizations of the Americas, should be left out of the account of Western accomplishments. Gress called upon historians to move away from an idealized image of Western uniqueness. Norman Davies, too, has criticized the way early Western civilization courses tended to “filter out anything that might appear mundane or repulsive” (A History of Europe, 1997: 28).

The Faustian Personality

I believe that Oswald Spengler’s identification of the West as “Faustian” provides us with the best word to overcome the current naïve separation between a cultured/peaceable West and an uncivilized/antagonistic West with his image of a strikingly vibrant culture driven by a type of Faustian personality overflowing with expansive, disruptive, and imaginative impulses manifested in all the spheres of life. For Spengler, the Faustian spirit was not restricted to the arts and sciences, but was present in the culture of the West at large. Spengler thus spoke of the “morphological relationship that inwardly binds together the expression-forms of all branches of Culture.” Rococo art, differential calculus, the Crusades, the Spanish conquest of the Americas were all expressions of the same restless soul. There is no incongruity between the “great ideas” of the West and the so-called “realities” of conquest and suffering. There is no need, from this standpoint, to concede to multicultural critics, as Norman Davies believes, “the sorry catalogue of wars, conflict, and persecutions that have dogged every stage of the [Western] tale” (p. 15-16). The expansionist dispositions of Europeans were not only indispensable but were themselves driven, as I argue in my book, The Uniqueness of Western Civilization, [9] and will briefly outline below, by an intensely felt desire to achieve great deeds and heroic immortality.

The great men of Europe were artists driven by an intensively felt desire for unmatched deeds. The “great ideas” – Archimedes’ “Give me a place to stand and with a lever I will move the whole world,” or Hume’s “love of literary fame, my ruling passion” – were associated with aristocratic traits, defiant dispositions – no less than Cortez’s immense ambition for honour and glory, “to die worthily than to live dishonoured.”

In contrast to Weber, for whom the West “exhibited an unrivaled aptitude for rationalization,” Spengler saw in this Faustian soul a primeval-irrational will to power. It was not a calmed, disinterested, rationalistic ethos that was at the heart of Western particularity; it was a highly energetic, goal-oriented desire to break through the unknown, supersede the norm, and achieve mastery. The West was governed by an intense urge to transcend the limits of existence, by a highly energetic, restless, fateful being, an “adamantine will to overcome and break all resistances of the visible” (Decline: pp. 185-86).

There was something Faustian about all the great men of Europe, both in reality and in fiction: in Hamlet, Richard III, Gauss, Newton, Nicolas Cusanus, Don Quixote, Goethe’s Werther, Gregory VII, Michelangelo, Paracelsus, Dante, Descartes, Don Juan, Bach, Wagner’s Parsifal, Haydn, Leibniz’s Monads, Giordano Bruno, Frederick the Great, Rembrandt, Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler.

The Faustian soul — whose being consists in the overcoming of presence, whose feeling is loneliness and whose yearning is infinity — puts its need of solitude, distance, and abstraction into all its actualities, into its public life, its spiritual and its artistic form-worlds alike (Decline: 386).

For Spengler, Christianity, too, became a thoroughly Faustian moral ethic. “It was not Christianity that transformed Faustian man, but Faustian man who transformed Christianity — and he not only made it a new religion but also gave it a new moral direction”: will-to-power in ethics (344). This “Faustian-Christian morale” produced

Christians of the great style — Innocent III, Loyola and Savonarola, Pascal and St. Theresa [ . . . ] the great Saxon, Franconia and Hohenstaufen emperors . . . giant-men like Henry the Lion and Gregory VII . . . the men of the Renaissance, of the struggle of the two Roses, of the Huguenot Wars, the Spanish Conquistadores, the Prussian electors and kings, Napoleon, Bismarck, Rhodes (348-49).

But what exactly is a Faustian soul? How do we connect it in a concrete way to Europe’s creativity? To what original source or starting place did Spengler attribute this yearning for infinity? To start answering this question we should first remind ourselves of Spengler’s other central idea, his cyclical view of history, according to which

- each culture contains a unique spirit of its own, and

- all cultures undergo an organic process of birth, growth, and decay.

In other words, for Spengler, all cultures exhibit a period of dynamic, youthful creativity; each culture experiences “its childhood, youth, manhood, and old age.” “Each culture has its own new possibilities of self-expression, which arise, ripen, decay and never return” (18-24, 106-07). Spengler thus drew a distinction between the earlier vital stages of a culture (Kultur) and the later stages when the life forces were on their last legs until all that remained was a superficial Zivilisation populated by individuals preoccupied with preserving the memories of past glories while drudging through the unexciting affairs of their everyday lives.

However, notwithstanding this emphasis on the youthful energies of all cultures, Spengler viewed the West as the most strikingly dynamic culture driven by a soul overflowing with expansive energies and “intellectual will to power.” By “youthful” he meant the actualization of the specific soul of each culture, “the full sum of its possibilities in the shape of peoples, languages, dogmas, arts, states, sciences.” Only in Europe he saw “directional energy,” march music, painters relishing in the use of blue and green, “transcendent, spiritual, non-sensuous colors,” “colours of the heavens, the seas, the fruitful plain, the shadow of the Southern noon, the evening, the remote mountains” (245-46). I think John Farrenkopf [10] has it right when he argues that Spengler’s appreciation for non-Western cultures as worthy subjects of comparative inquiry came together with an “exaltation” of the greater creative energy of the West (2001: 35).

But what about Spengler’s repetitive insistence that ancient Greece and Rome were not Faustian? Although I agree with Spengler that in certain respects the Greek-Roman “soul” was oriented toward the present rather than the future, and that its architecture, geometry, and finite mathematics were bounded spatially, restrained, and perceptible, he overstates his argument about the lack of an expansionist spirit, downplaying the incredible creative energies of Greeks and Romans, their individual heroism and urge for the unknown. Farrenkopf thinks that the later Spengler came to view the Greeks and Romans as more individualistic and dynamic. I agree with Burckhardt that the Classical Greeks were singularly agonal and individualistic, and with Nietzsche’s insight that all that was civilized and rational among the Greeks would have been impossible without this agonal culture. The ancient Greeks who established colonies throughout the Mediterranean, the Macedonians who marched to “the ends of the world,” and the Romans who created the greatest empire in history, were similarly driven, to use Spengler’s term, by an “irrepressible urge to distance” as the Germanic peoples who brought Rome down, the Vikings who crossed the Atlantic, the Crusaders who wrecked havoc on the Near East, and the Portuguese who pushed themselves with their gunned ships upon the previously tranquil world of the Indian Ocean. Spengler does not persuade in his efforts to downplay this Faustian side of the Greeks and Romans.

What was the ultimate original ground of the West’s Faustian soul? There are statements in Spengler which make references to “a Nordic world stretching from England to Japan” and a “harder-struggling” people, and a more individualistic and heroic spirit “in the old, genuine parts of the Mahabharata . . . in Homer, Pindar, and Aeschylus, in the Germanic epic poetry and in Shakespeare, in many songs of the Chinese Shuking, and in circles of the Japanese samurai” (as cited in Farrenkopf: 227). Spengler makes reference to the common location of these peoples in the “Nordic” steppes. He does not make any specific reference to the Caucasian steppes but he clearly has in mind the “Aryan Indian” peoples who came out of the steppes and conquered India and wrote the Mahabharata. He calls “half Nordic” the Graeco-Roman, Aryan Indian, and Chinese high cultures. In Man and Technics, he writes of how the Nordic climate forged a man filled with vitality

What was the ultimate original ground of the West’s Faustian soul? There are statements in Spengler which make references to “a Nordic world stretching from England to Japan” and a “harder-struggling” people, and a more individualistic and heroic spirit “in the old, genuine parts of the Mahabharata . . . in Homer, Pindar, and Aeschylus, in the Germanic epic poetry and in Shakespeare, in many songs of the Chinese Shuking, and in circles of the Japanese samurai” (as cited in Farrenkopf: 227). Spengler makes reference to the common location of these peoples in the “Nordic” steppes. He does not make any specific reference to the Caucasian steppes but he clearly has in mind the “Aryan Indian” peoples who came out of the steppes and conquered India and wrote the Mahabharata. He calls “half Nordic” the Graeco-Roman, Aryan Indian, and Chinese high cultures. In Man and Technics, he writes of how the Nordic climate forged a man filled with vitality

through the hardness of the conditions of life, the cold, the constant adversity, into a tough race, with an intellect sharpened to the most extreme degree, with the cold fervor of an irrepressible passion for struggling, daring, driving forward.

Principally, he mentions the barbarian peoples of northern Europe, whose world he contrasts to “the languid world-feeling of the South” (Farrenkopf: 222). Spengler does not deny the environment, but rather than focusing on economic resources and their “critical” role in the industrialization process, he draws attention to the profound impact environments had in the formation of distinctive psychological orientations amongst the cultures of the world. He thinks that the Faustian form of spirituality came out of the “harder struggling” climes of the North. The Nordic character was less passive, less languorous, more energetic, individualistic, and more preoccupied with status and heroic deeds than the characters of other climes. He was a human biological being to be sure, but one animated with the spirit of a “proud beast of prey [11],” like that of an “eagle, lion, [or] tiger.” Much like Hegel’s master who engages in a fight to the death for pure prestige, for this “Nordic” individual “the concerns of life, the deed, became more important than mere physical existence” (Man and Technics: A Contribution to a Philosophy of Life, Greenwood Press, 1976: 19-41).

This deed-oriented man is not satisfied with a Darwinian struggle for existence or a Marxist struggle for economic equality. He wants to climb high, soar upward and reach ever higher levels of existential intensity. He is not preoccupied with mere adaptation, reproduction, and conservation. He wants to storm into the heavens and shape the world. But who exactly is this character? Is he the Hegelian master who fights to the death for the sake of prestige? Spengler paraphrases Nietzsche when he writes that the primordial forces of Western culture reflect the “primary emotions of an energetic human existence, the cruelty, the joy in excitement, danger, the violent act, victory, crime, the thrill of a conqueror and destroyer.” Nietzsche too wrote of the “aristocratic” warrior who longed for the “proud, exalted states of the soul,” as experienced intimately through “combat, adventure, the chase, the dance, war games” (The Genealogy of Morals, 1956: 167). Who are these characters? Are their “primary emotions” any different from humans in other cultures?

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2015/01/oswald-spengler-and-the-faustian-soul-of-the-west-part-1/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Faust-im-Studierzimmer-Georg-Friedrich-Kersting.jpg

[2] Indo-European speakers: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DpbjquTQT98

[3] most mobile way of life in prehistoric times: http://press.princeton.edu/titles/8488.html

[4] vital illustrations of spatial expansionism: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SiIXC1U8HNo

[5] first rational theology in history: http://www.cambridge.org/us/academic/subjects/history/history-science-and-technology/god-and-reason-middle-ages

[6] invention of universities: http://www.cambridge.org/ca/academic/subjects/history/european-history-1000-1450/first-universities-studium-generale-and-origins-university-education-europe

[7] Human Accomplishment: The Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts and Sciences, 800 B.C. to 1950: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0060929642/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=0060929642&linkCode=as2&tag=countecurrenp-20&linkId=RSAI5XD63BIRHVZ5

[8] Grand Narrative: http://www.nytimes.com/books/first/g/gress-plato.html

[9] The Uniqueness of Western Civilization,: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/.UdQ80Ds6Oxo#.VAhMZPldVOw

[10] John Farrenkopf: http://www.arktos.com/john-farrenkopf-prophet-of-decline.html

[11] beast of prey: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DLkeIACfi4Y&list=UUIfnKm98q78j2ZNcfSQhhCQ&index=3

Oswald Spengler & the Faustian Soul of the West,

Part 2

By Ricardo Duchesne

Kant and the “Unsocial Sociability” of Humans

I ended Part 1 [2] asking who are these characters with proud aristocratic souls so different from the rather submissive, slavish souls of the Asiatic races. A good way to start answering this question is to compare Spengler’s Faustian man with what Immanuel Kant says about the “unsocial sociability” of humans generally. In his essay, “Idea for a Universal History from a Cosmopolitan Point of View,” Kant seemed somewhat puzzled but nevertheless attuned to the way progress in history had been driven by the fiercer, self-centered side of human nature. Looking at the wide span of history, he concluded that without the vain desire for honor, property, and status humans would have never developed beyond a primitive Arcadian existence of self-sufficiency and mutual love:

all human talents would remain hidden forever in a dormant state, and men, as good-natured as the sheep they tended, would scarcely render their existence more valuable than that of their animals . . . [T]he end for which they were created, their rational nature, would be an unfulfilled void.

There can no development of the human faculties, no high culture, without conflict, aggression, and pride. It is these asocial traits, “vainglory,” “lust for power,” “avarice,” which awaken the otherwise dormant talents of humans and “drive them to new exertions of their forces and thus to the manifold development of their capacities.” Nature in her wisdom, “not the hand of an evil spirit,” created “the unsocial sociability of humans.”

There can no development of the human faculties, no high culture, without conflict, aggression, and pride. It is these asocial traits, “vainglory,” “lust for power,” “avarice,” which awaken the otherwise dormant talents of humans and “drive them to new exertions of their forces and thus to the manifold development of their capacities.” Nature in her wisdom, “not the hand of an evil spirit,” created “the unsocial sociability of humans.”

But Kant never asked, in this context, why Europeans were responsible, in his own estimation, for most of the moral and rational progression in history. Separately, in another publication, Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View [3] (1798), Kant did observe major differences in the psychological and moral character of humans as exhibited in different places on earth, ranking human races accordingly, with Europeans at the top in “natural traits”. Still, Kant never connected his anthropology with his principle of asocial qualities.

Did “Nature” foster these asocial qualities evenly among the cultures of the world? While these “vices” — as we have learned today from evolutionary psychology — are genetically-based traits that evolved in response to long periods of adaptive selective pressures associated with the maximization of human survival, there is no reason to assume that the form and degree of these traits evolved evenly or equally among all the human races and cultures. It is my view that the asocial qualities of Europeans were different, more intense, strident, individuated.

Indo-European Aristocratic Lifestyle

I believe that this variation should be traced back to the aristocratic lifestyle of Indo-Europeans. Indo-Europeans were a pastoral people from the Pontic-Caspian steppes who initiated the most mobile way of life in prehistoric times starting with the riding of horses and the invention of wheeled vehicles in the fourth millennium BC, together with the efficient exploitation of the “secondary products” of domestic animals (dairy products, textiles, harnessing of animals), large-scale herding, and the invention of chariots in the second millennium. By the end of the second millennium, even though Indo-Europeans invaded both Eastern and Western lands, only the Occident had been “Indo-Europeanized [4].”

Indo-Europeans were also uniquely ruled by a class of free aristocrats. In very broad terms, I define as “aristocratic” a state in which the ruler, the king, or the commander-in-chief is not an autocrat who treats the upper classes as unequal servants but is a “peer” who exists in a spirit of equality as one more warrior of noble birth, primus inter pares [5]. This is not to say that leaders did not enjoy extra powers and advantages, or that leaders were not tempted to act in tyrannical ways. It is to say that in aristocratic cultures, for all the intense rivalries between families and individuals seeking their own renown, there was a strong ethos of aristocratic egalitarianism against despotic rule. A true aristocratic deserving respect from his peers could not be submissive; his dignity and honor as a man were intimately linked to his capacity for self-determination.

Different levels of social organization characterized Indo-European society. The lowest level, and the smallest unit of society, consisted of families residing in farmsteads and small hamlets, practicing mixed farming with livestock representing the predominant form of wealth. The next tier consisted of a clan of about five families with a common ancestor. The third level consisted of several clans — or a tribe — sharing the same. Those members of the tribe who owned livestock were considered to be free in the eyes of the tribe, with the right to bear arms and participate in the tribal assembly.

Although the scale of complexity of Indo-European societies changed considerably with the passage of time, and the Celtic tribal confederations that were in close contact with Caesar’s Rome during the 1st century BC, for example, were characterized by a high concentration of economic and political power, these confederations were still ruled by a class of free aristocrats. In classic Celtic society, real power within and outside the tribal assembly was wielded by the most powerful members of the nobility, as measured by the size of their clientage and their ability to bestow patronage. Patronage could be extended to members of other tribes and to free individuals who were lower in status and were thus tempted to surrender some of their independence in favor of protection and patronage.

Indo-European nobles were also grouped into war-bands. These bands were freely constituted associations of men operating independently from tribal or kinship ties. They could be initiated by any powerful individual on the merits of his martial abilities. The relation between the chief and his followers was personal and contractual: the followers would volunteer to be bound to the leader by oaths of loyalty wherein they would promise to assist him while the leader would promise to reward them from successful raids. The sovereignty of each member was thus recognized even though there was a recognized leader. These “groups of comrades,” to use Indo-European vocabulary, were singularly dedicated to predatory behavior and to “wolf-like” living by hunting and raiding, and to the performance of superior, even superhuman deeds. The members were generally young, unmarried men, thirsting for adventure. The followers were sworn not to survive a war-leader who was slain in battle, just as the leader was expected to show in all circumstances a personal example of courage and war-skills.

Young men born into noble families were not only driven by economic needs and the spirit of adventure, but also by a deep-seated psychological need for honor and recognition — a need nurtured not by nature as such but by a cultural setting in which one’s noble status was maintained in and through the risking of one’s life in a battle to the death for pure prestige. This competition for fame among war-band members (partially outside the ties of kinship) could not but have had an individualizing effect upon the warriors. Hence, although band members (“friend-companions” or “partners”) belonged to a cohesive and loyal group of like-minded individuals, they were not swallowed up anonymously within the group.

The Indo-European lifestyle included fierce competition for grazing rights, constant alertness in the defense of one’s portable wealth, and an expansionist disposition in a world in which competing herdsmen were motivated to seek new pastures as well as tempted to take the movable wealth (cattle) of their neighbors. This life required not just the skills of a butcher but a life span of horsemanship and arms (conflict, raids, violence) which brought to the fore certain mental dispositions including aggressiveness and individualism, in the sense that each individual, in this male-oriented atmosphere, needed to become as much a warrior as a herds-man.

The most important value of Indo-European aristocrats was the pursuit of individual glory as members of their warbands and as judged by their peers. The Iliad, Beowulf, Song of Roland, including such Irish, Icelandic and Germanic Sagas as Lebor na hUidre, Njals Saga, Gisla Saga Sursonnar, The Nibelungenlied recount the heroic deeds and fame of aristocrats — these are the earliest voices from the dawn of Western civilization. Within this heroic ‘life-world’ the unsocial traits of humans took on a sharper, keener, individuated expression.

What about other central Asian peoples from the steppes such as the Mongols and Turks who produced a similar heroic literature? There are a number of substantial differences. First, the Indo-European epic and heroic tradition precedes any other tradition by some thousands of years, not just the Homeric and the Sanskrit epics but, as we now know with some certainty from such major books as M. L. West’s Indo-European Poetry and Myth, and Calvert Watkins’s How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of IE Poetics (1995), going back to a prehistoric oral tradition. Second, IE poetry exhibits a keener grasp and rendition of the fundamentally tragic character of life, an aristocratic confidence in the face of destiny, the inevitability of human hardship and hubris, without bitterness, but with a deep joy.

Third, IE epics show both collective and individual inspiration, unlike non-IE epics which show characters functioning only as collective representations of their communities. This is why in some IE sagas there is a clear author’s stance, unlike the anonymous non-IE sages; the individuality, the rights of authorship, the poet’s awareness of himself as creator, is acknowledged in many ancient and medieval European sagas (see Hans Gunther, Religious Attitudes of the Indo-Europeans [1963] 2001, and Aaron Gurevich, The Origins of European Individualism [6], 1995).

Nietzsche and Sublimation of the Agonistic Ethos of Indo-European Barbarians

But how do we connect the barbaric asocial traits of prehistoric Indo-European warriors to the superlative cultural achievements of Greeks and later civilized Europeans? Nietzsche provides us some keen insights as to how the untamed agonistic ethos of Indo-Europeans was translated into civilized creativity. In his fascinating early essay, “Homer on Competition” (1872), Nietzsche observes that civilized culture or convention (nomos) was not imposed on nature but was a sublimated continuation of the strife that was already inherent to nature (physis). The nature of existence is based on conflict and this conflict unfolded itself in human institutions and governments. Humans are not naturally harmonious and rational as Socrates had insisted; the nature of humanity is strife. Without strife there is no cultural development. Nietzsche argued against the separation of man/culture from nature: the cultural creations of humanity are expressions or aspects of nature itself.

But how do we connect the barbaric asocial traits of prehistoric Indo-European warriors to the superlative cultural achievements of Greeks and later civilized Europeans? Nietzsche provides us some keen insights as to how the untamed agonistic ethos of Indo-Europeans was translated into civilized creativity. In his fascinating early essay, “Homer on Competition” (1872), Nietzsche observes that civilized culture or convention (nomos) was not imposed on nature but was a sublimated continuation of the strife that was already inherent to nature (physis). The nature of existence is based on conflict and this conflict unfolded itself in human institutions and governments. Humans are not naturally harmonious and rational as Socrates had insisted; the nature of humanity is strife. Without strife there is no cultural development. Nietzsche argued against the separation of man/culture from nature: the cultural creations of humanity are expressions or aspects of nature itself.

But nature and culture are not identical; the artistic creations of humans, their norms and institutions, constitute a re-channeling of the destructive striving of nature into creative acts, which give form and aesthetic beauty to the otherwise barbaric character of natural strife. While culture is an extension of nature, it is also a form by which human beings conceal their cruel reality, and the absurdity and the destructiveness of their nature. This is what Nietzsche meant by the “dual character” of nature; humans restrain or sublimate their drives to create cultural artifacts as a way of coping with the meaningless destruction associated with striving.

Nietzsche, in another early publication, The Birth of Tragedy (1872), referred to this duality of human existence, nomos and physis, as the “Apollonian and Dionysian duality.” The Dionysian symbolized the excessive and intoxicating strife which characterized human life in early tribal societies, whereas the Apollonian symbolized the restraint and re-channeling of conflict possible in state-organized societies. In the case of Greek society, during pre-Homeric times, Nietzsche envisioned a world in which there were no or few limits to the Dionysian impulses, a time of “lust, deception, age, and death.” The Homeric and classical (Apollonian) inhabitants of city-states brought these primordial drives under “measure” and self-control. The emblematic meaning of the god Apollo was “nothing in excess.” Apollo was a provider of soundness of mind, a guardian against a complete descent into a state of chaos and wantonness. He was a redirector of the willful and hubristic yearnings of individuals into organized forms of warfare and higher levels of art and philosophy.

For Nietzsche, Greek civilization was not produced by a naturally harmonious character, or a fully moderated and pacified city-state. One of the major mix-ups all interpreters of the rise of the West fall into is to assume that Western achievements were about the overcoming and suppression of our Dionysian impulses. But Nietzsche is right: Greeks achieved their “civility” by attuning, not denying or emasculating, the destructive feuding and blood lust of their Dionysian past and placing their strife under certain rules, norms and laws. The limitless and chaotic character of strife as it existed in the state of nature was made “civilized” when Greeks came together within a larger political horizon, but it was not repressed. Their warfare took on the character of an organized contest within certain limits and conventions. The civilized aristocrat was the one who, in exercising sovereignty over his powerful longings (for sex, booze, revenge, and any other kind of intoxicant) learned self-command and, thereby, the capacity to use his reason to build up his political power and rule those “barbarians” who lacked this self-discipline. The Greeks created their admirable culture while remaining at ease with their superlative will to strife.

The problem with Nietzsche is lack of historical substantiation. The research now exists to add to Nietzsche the historically based argument that the Greeks viewed the nature of existence as strife because of their background in an Indo-European state of nature where strife was the overriding ethos. There are strong reasons to believe that Nietzsche’s concept of strife is an expression of his own Western background and his study of the Western agonistic mode of thinking that began with the Greeks. One may agree that strife is in the “nature of being” as such, but it is worth noting that, for Nietzsche, not all cultures have handled nature’s strife in the same way and not all cultures have been equally proficient in the sublimated production of creative individuals or geniuses. Nietzsche thus wrote of two basic human responses to the horror of endless strife: the un-Hellenic tendency to renounce life in this world as “not worth living,” leading to a religious call to seek a life in the beyond or the after-world, or the Greek tragic tendency, which acknowledged this strife, “terrible as it was, and regarded it as justified.” The cultures that came to terms with this strife, he believed, were more proficient in the completion of nature’s ends and in the production of creative individuals willing to act in this world. He saw Heraclitus’ celebration of war as the father and king of the whole universe as a uniquely Greek affirmation of nature as strife. It was this affirmation which led him to say that “only a Greek was capable of finding such an idea to be the fundament of a cosmology.”

The Greek speaking aristocrats had to learn to come together within a political community that would allow them to find some common ground and thus move away from the “state of nature” with its endless feuding and battling for individual glory. There would emerge in the 8th century BC a new type of political organization, the city-state. The greatness of Homeric and Classical Greece involved putting Apollonian limits around the indispensable but excessive Dionysian impulses of barbaric pre-Homeric Greeks. Ionian literature was far from the berserkers of the pre-Homeric world, but it was just as intensively competitive. The search for the truth was a free-for-all with each philosopher competing for intellectual prestige in a polemical tone that sought to discredit the theories of others while promoting one’s own. There were no Possessors of the Way in aristocratic Greece; no Chinese Sages decorously deferential to their superiors and expecting appropriate deference from their inferiors.

This agonistic ethos was ingrained in the Olympic Games, in the perpetual warring of the city-states, in the pursuit of a political career and in the competition among orators for the admiration of the citizens, and in the Athenian theater festivals where a great many poets would take part in Dionysian competitions. It was evident in the sophistic-Socratic ethos of dialogic argument and the pursuit of knowledge by comparing and criticizing individual speeches, evaluating contradictory claims, collecting out evidence, competitive persuasion and refutation. And in the Catholic scholastic method, according to which critics would engage major works, read them thoroughly, compare the book’s theories to other authorities, and through a series of dialogical exercises ascertain the respective merits and demerits.

This agonistic ethos was ingrained in the Olympic Games, in the perpetual warring of the city-states, in the pursuit of a political career and in the competition among orators for the admiration of the citizens, and in the Athenian theater festivals where a great many poets would take part in Dionysian competitions. It was evident in the sophistic-Socratic ethos of dialogic argument and the pursuit of knowledge by comparing and criticizing individual speeches, evaluating contradictory claims, collecting out evidence, competitive persuasion and refutation. And in the Catholic scholastic method, according to which critics would engage major works, read them thoroughly, compare the book’s theories to other authorities, and through a series of dialogical exercises ascertain the respective merits and demerits.

In Spengler’s language, this Faustian soul was present in “the Viking infinity wistfulness,” and their colonizing activities through the North Sea, the Atlantic, and the Black Sea. In the Portuguese and Spaniards who “were possessed by the adventured-craving for uncharted distances and for everything unknown and dangerous.” In “the emigration to America,” “the Californian gold-rush,” “the passion of our Civilization for swift transit, the conquest of the air, the exploration of the Polar regions and the climbing of almost impossible mountain peaks” — “dramas of uncontrollable longings for freedom, solitude, immense independence, and of giant-like contempt for all limitations.” “These dramas are Faustian and only Faustian. No other culture, not even the Chinese, knows them” (335-37).

The West has clearly been facing a spiritual decline for many years now as Spengler observed despite its immense technological innovations, which Spengler acknowledged, observing how Europe, after 1800, came to be thoroughly dominated by a purely “mechanical” expression of this Faustian tendency in its remorseless expansion outward through industrial capitalism with its ever-growing markets and scientific breakthroughs. Spengler did not associate this mechanical (“Anglo-Saxon”) expansion with cultural creativity per se. Before 1800, the energy of Europe’s Faustian culture was still expressed in “organic” terms; that is, it was directed toward pushing the frontiers of inner knowledge through art, literature, and the development of the nation state. It was during the 1800s that the West, according to him, entered “the early Winter of full civilization” as its culture took on a purely capitalistic and mechanical character, extending itself across the globe, with no more “organic” ties to community or soil. It was at this point that this rootless rationalistic Zivilisation had come to exhaust its creative possibilities, and would have to confront “the cold, hard facts of a late life. . . . Of great paintings or great music there can no longer be, for Western people, any question” (Decline of the West, Vol. I: 20-21; Vol II: 46, 44, 40).

The decline of the organic Faustian soul is irreversible but there is reason to believe that decline is cyclical and not always permanent — as we have seen most significantly in the case of China many times throughout her history. European peoples need not lose their superlative drive for technological supremacy. The West can re-assert itself, unless the cultural Marxists are successful in their efforts to destroy this Faustian spirit permanently through mass immigration and miscegenation.

Source: http://www.eurocanadian.ca/2014/09/oswald-spengler-and-faustian-soul-of_8.html [7]

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2015/01/oswald-spengler-and-the-faustian-soul-of-the-west-part-2/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Apollos.jpg

[2] Part 1: http://www.counter-currents.com/2015/01/oswald-spengler-and-the-faustian-soul-of-the-west-part-1/

[3] Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View: http://www.cambridge.org/us/academic/subjects/philosophy/philosophy-texts/kant-anthropology-pragmatic-point-view

[4] Indo-Europeanized: http://books.google.ca/books/about/The_Kurgan_Culture_and_the_Indo_European.html?id=hCZmAAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y

[5] primus inter pares: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Primus_inter_pares

[6] The Origins of European Individualism: http://books.google.ca/books/about/The_Origins_of_European_Individualism.html?id=QrksZOjpURYC&redir_esc=y

[7] http://www.eurocanadian.ca/2014/09/oswald-spengler-and-faustian-soul-of_8.html: http://www.eurocanadian.ca/2014/09/oswald-spengler-and-faustian-soul-of_8.html

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : esprit faustien, âme faustienne, faust, oswald spengler, allemagne, révolution conservatrice, philosophie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les commentaires sont fermés.