By Ricardo Duchesne

Ex: https://fortnightlyreview.co.uk

IN HIS 2003 book, Human Accomplishment: Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts and Sciences, 800 BC to 1950, Charles Murray argued that the great artistic and scientific accomplishments were overwhelmingly European. ”What the human species is today,” he wrote, “it owes in astonishing degree to what was accomplished in just half a dozen centuries by the peoples of one small portion of the northwestern Eurasian land mass.”

This claim goes against the modern grain of the world history community – indeed, against fashionable belief. The New York Times unsurprisingly called it “more bluster than rigor” and “unconvincing”1, but it was nonetheless the first attempt to quantify “as facts” the creative genius of individuals in terms of cultural origin and geographic distribution. Murray did this by calculating the amount of space allocated to these individuals in reference works, encyclopedias, and dictionaries. Based on this metric, he concluded that “whether measured in people or events, 97 percent of accomplishment in the sciences occurred in Europe and North America” from 800 BC to 1950. Murray’s inventories of the arts also confirmed the overpowering role of Europe, particularly after 1400. Although Murray did not compare their achievements but compiled separate lists for each civilization, he noted that the sheer number of “significant figures” in the arts is higher in the West in comparison to the combined number of the other civilizations. He explained this remarkable “divergence” in human accomplishments in terms of the degree to which cultures promote or discourage autonomy and purpose. I am persuaded that individualism is one of the critical variables.2

The point I want to make, however, is that Murray pays no attention to accomplishments in other human endeavors such as leadership, exploration, and heroic deeds. The achievements he measures come only in the form of “great books” and “great ideas.” In this respect, Murray’s book is similar to certain older-style Western Civ textbooks where the progression of modern liberal ideals is the central theme. David Gress dubbed this type of historiography the “Grand Narrative.” By teaching Western history in terms of the realization of liberal democratic values, these texts “placed a burden of justification on the West … to explain how the reality differed from the ideal.’3 Gress called upon historians to do away with this idealized image of Western uniqueness and to emphasize the realities of Western geopolitical struggles and mercantile interests. Norman Davies, too, has criticized the way early Western civilization courses tended to “filter out anything that might appear mundane or repulsive.”4

MY VIEW IS that Europeans were not only exceptional in their literary endeavors, but also in their agonistic and expansionist behaviors. Their great books, including their liberal values, were themselves inseparably connected to their aristocratic ethos of competitive individualism. There is no need to concede to multicultural critics, as Davies does, “the sorry catalogue of wars, conflict, and persecutions that have dogged every stage of the [Western] tale.”5 The expansionist dispositions of Europeans as well as their literary and other achievements were similarly driven by an aggressive and individually felt desire for superlative and undemocratic recognition.

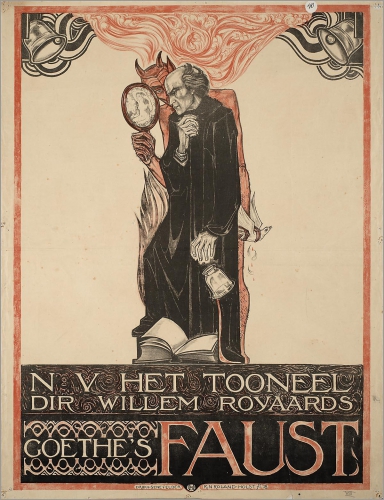

It has been said that when Mahatma Gandhi was asked what he thought of Western civilization he answered, “I think it would be a good idea.” Academics today interpret this answer to mean that the actual history of the West—such things as the conquest of the Americas and the expansion of the British Empire— belie its great ideas and great books. I challenge this naïve separation between an idealized and a realistic West borrowing Oswald Spengler’s image of the West as a strikingly vibrant culture driven by a type of personality overflowing with expansive, disruptive, and creative impulses. Spengler designated the West as a “Faustian” culture whose “prime-symbol” was “pure and limitless space.” This spirit was first visible in medieval Europe, starting with Romanesque art, but particularly in the “spaciousness of Gothic cathedrals;” “the heroes” of the Scandinavian, Germanic, and Icelandic sagas; the Crusades; the Viking sailing of the North Atlantic Ocean; the Germanic conquest of the Slavonic East; the Spaniards in the Americas; and the Portuguese in the East Indies.6

“Fighting,” “progressing,” “overcoming of resistances,” struggling “against what is near, tangible and easy”—these are some of the terms Spengler used to describe this soul. This Faustian being is animated with the spirit of a “proud beast of prey,” like that of an “eagle, lion, [or] tiger.” Moreover, the seemingly peaceful achievements of the West, not just its warlike activities, were infused with this Faustian impulse. As John Farrenkopf puts it:

[T]he architecture of the Gothic cathedral expresses the Faustian will to conquer the heavens; Western symphonic music conveys the Faustian urge to conjure up a dynamic, transcendent, infinite space of sound; Western perspective painting mirrors the Faustian will to infinite distance; and the Western novel responds to the Faustian imperative to explore the inner depths of the human personality while extending outward with a comprehensive view.7

IN MY BOOK, The Uniqueness of Western Civilization, I trace the West’s Faustian creativity and libertarian spirit back to the aristocratic warlike culture of Indo-European speakers who began to migrate into Europe roughly after 3500 BC, combining with and subordinating the ‘ranked’ Neolithic cultures of this region. Indo-European speakers originated in the Pontic-Caspian steppes. They initiated the most mobile way of life in prehistoric times, starting with the riding of horses and the invention of wheeled vehicles in the fourth millennium BC, together with the efficient exploitation of the “secondary products” of domestic animals (dairy goods, textiles, large-scale herding), and the invention of chariots in the second millennium. The novelty of Indo-European culture was that it was led by an aristocratic elite that was egalitarian within the group rather than by a single despotic ruler. Indo-Europeans prized heroic warriors striving for individual fame and recognition, often with a “berserker” style of warfare. In the more advanced and populated civilizations of the Near East, Iran, and India, local populations absorbed this conquering group. In Neolithic Europe, the Indo-Europeans imposed themselves as the dominant group, and displaced the native languages but not the natives.

I maintain that the history of European explorations stands as an excellent subject matter for the elucidation of this Faustian restlessness. An overwhelming number of the explorers in history have been European. The Concise Encyclopedia of Explorers lists a total of 274 explorers, of which only 15 are non-European, with none listed after the mid-fifteenth century.8 In the urge to explore new regions of the earth and map the nameless, we can detect, in a crystallized way, the “prime-symbol” of Western restlessness. We can also detect the Western mind’s desire – if I may borrow the language of Hegel – to expand its cognitive horizon, to “subdue the outer world to its ends with an energy which has ensured for it the mastery of the world.”9

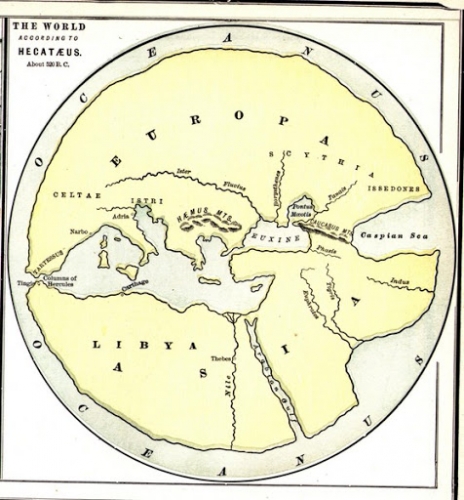

The Greeks initiated the science of geography. But just as pertinent is how contentious individuals, born in a culture engaged in widespread colonizing activities between 800 and 500 BC, drove this science. Hecataeus (550 – 476 BC), the author of the first book of geography, Journey Round the World, based his knowledge on his extensive travels along the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. To be sure, the Phoenicians, starting around the first millennium BC, established approximately 30 colonies throughout the African shores in the western Mediterranean, Sardinia, Malta, and as far west as Cádiz in modern Spain. However, more than thirty Greek city-states each established multiple colonies, with some estimating that the city of Miletus alone set up ninety colonies. All in all, Greek colonies were stretched throughout the Mediterranean coasts, the shores of the Black Sea, Anatolia in the east, southern France, Italy, Sicily, and in the northern coast of Africa, not to mention the long colonized islands of the Aegean Sea.

A popular explanation as to why the Greeks launched these overseas colonies is population growth and scarce resources at home. But the evidence shows that much of these colonial operations were small-scale undertakings rather than mass migrations led by impoverished farmers. Commercial interests and the incentive to gain new agricultural lands were motivating factors. But I would also emphasize the “general spirit of adventure” permeating the Greek world since Mycenaean times. Many of the colonies, as A. G. Woodhead has shown, had “their origins in purely individual enterprise or extraordinary happenings.”10

Hecataeus envisioned the world as a disc surrounded by an ocean. But soon there would be a challenger – Herodotus, born in 484BC. He too offered numerous geographical and ethnographic insights based on his extensive travels, and he did so in explicit awareness of his own contributions and in direct criticism of his predecessor. This competitive desire on the part of individuals to stand out from others was ingrained in the whole social outlook of classical Greece: in the Olympic Games, in the perpetual warring of the city-states, in the pursuit of a political career, in the competition among orators for the admiration of the citizens, and in the Athenian theater festivals, where numerous poets would take part in Dionysian competitions amid high civic splendor and religious ritual. New works of drama, philosophy, and music were expounded in the first-person form as an adversarial or athletic contest in the pursuit of truth.

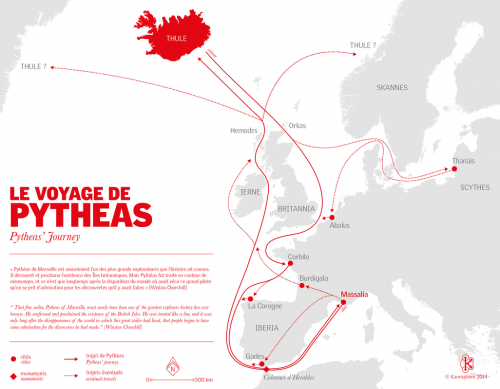

DURING THE HELLENISTIC centuries, explorers would venture into the Caspian, Aral, and Red Seas, establishing trading posts along the coasts of modern Eritrea and Somalia. Perhaps the most successful of Hellenistic explorers was Pytheas. In his book, On the Ocean, he recounts an amazing journey (ca. 310BC) northward to Brittany across the Channel into Cornwall, through the Baltic Sea, the coast of Norway, and even Iceland.11

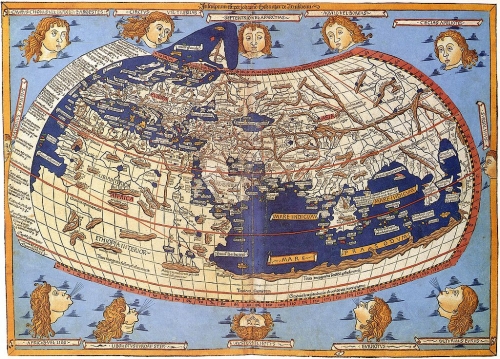

These explorations encouraged astronomical and geographical scholarship leading to the full conceptualization of the shape of the earth itself by Eratosthenes (276-185BC), who not only contextualized the location of Europe in relation to the Atlantic and the North Sea, but calculated the spherical size of the earth (within 5 percent of its true measure), with the obvious implication that the Mediterranean was only a small portion of the globe. This spirit of inquiry continued through the second century AD, when Ptolemy wrote his System of Astronomy and his Geography, where he rationally explained the principles and methods required in mapmaking and produced the first world map depicting India, China, South-East Asia, the British Isles, Denmark and East Africa.

There was far less desire to explore the geography and landscapes of the world among the peoples of the non-Western world. While in the first century BC the Han dynasty extended its geographical boundaries south into Vietnam, north into Korea, and east into the Tarim Basin, the Chinese showed little geographical interest beyond their own borders. What is striking about Chinese maps in general is how insular they were in comparison with the much earlier maps of Ptolemy. Even a sixteenth-century reproduction of Zheng He’s sailing maps lacks any apposite scale, size, and sense of proportion regarding the major landmasses of the earth.

The Chinese supposition that the earth was flat remained almost unchanged from ancient times until Jesuit missionaries in the seventeenth century brought modern ideas. In stark contrast, Greek philosophers of the fifth and fourth centuries BC were already persuaded that the earth was a sphere. Aristarchus of Samos, who lived about 310 to 230 BC, went so far as to postulate the Copernican hypothesis that all planets revolve in circles around the sun, and that the earth rotates on its axis once in twenty-four hours.

Indian civilization showed little curiosity about the geography of the world; its maps were symbolic and removed from any empirical concern with the actual location of places. Maritime activity among the isolated civilizations of America was restricted to fishing from rafts and canoes. The Phoenicians left no geographical documents of their colonizing expeditions.12

The Vikings “discovered in their gray dawn the art of sailing the seas which emancipated them”—so says Spengler.13 During the last years of the eighth century, marauding bands of Vikings pillaged their way along the coast lines of Northern Europe and down around Spain, into the Mediterranean, Italy, North Africa, and Arabia. Some hauled their long boats overland from the Baltic and made their way down the great Russian rivers all the way to the Black Sea. During the ninth and tenth centuries, their primary aim was no longer plunder as much as finding new lands to settle. Their voyages far into the North Atlantic were “independent undertakings, part of a 300-year epoch of seaborne expansion” which resulted in the settlement of Scandinavian peoples in Shetland, Orkney, the Hebrides, parts of Scotland and Ireland, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland (present-day Newfoundland).14 They colonized the little-known and unknown lands of Iceland from 870AD onward, Greenland from 980 onward, and then Vinland by the year 1000 AD. The Icelandic geographers of the Middle Ages showed considerable detailed knowledge in their descriptions of the Arctic regions, stretching from Russia to Greenland, and of the eastern seaboard of the North American continent. This is clearly attested in an Icelandic Geographical Treatise preserved in a manuscript dating from about 1300, but possibly based on a twelfth-century original.

Peter Whitfield speculates that “some conscious impulse towards exploration and conquest” must have motivated these voyages, “prompted by harsh living conditions at home.”15 Jesse Byock explains that the settlement of Iceland was led by sailor-farmers seeking to escape population pressures in the Scandinavian mainland, and that, in turn, the settlement of Greenland was initiated by Icelanders escaping Malthusian pressures in Iceland. At the same time, the cultural world Byock reveals, through his careful reading of numerous heroic sagas associated with these voyages and settlements, is that of aristocratic chieftains and free farmers venturing into unknown lands, competing with other chieftains and struggling for survival and renown.16

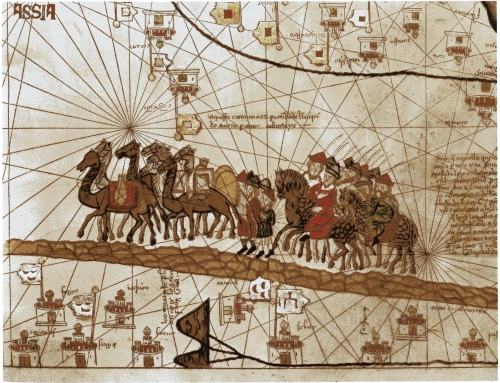

In the next centuries after the Vikings, the travels of Marco Polo (1254-1324) throughout the Asian world found expression in the Catalan Atlas of 1375, which was quite innovative in showing compass-lines, and in the accurate delineation of the Mediterranean. On the strength of Ptolemy’s work, Islam fostered its own geographical tradition with the benefit of their extensive dominions and travels. Ibn Battuta (1304-1374), the greatest Muslim traveler, visited every Muslim country and neighboring lands. But his “overmastering impulse,” to use his own words, was to visit “illustrious sanctuaries”17 – unlike Marco Polo’s desire, which was to visit non-Christian lands barely visited by Europeans and learn about the unknown tribes of Asia, including the numinous land of Cathay.18 In 1154, the greatest Islamic cartographer, al-Idrisi, produced a large planispheric silver relief map that was original in not portraying the Indian Ocean in a landlocked way and in offering a more precise knowledge of China’s eastern coast. But Islamic geography would go no further.

SPENGLER WRITES THAT the Spaniards and the Portuguese “were possessed by the adventured-craving for uncharted distances and for everything unknown and dangerous.’19 By the beginning of the 1400s, the compass, the portolan chart and certain shipping techniques essential for launching the Age of Exploration were in place. The Portuguese, under the leadership of Henry the Navigator would go on, in the course of the fifteenth century, to round the southern tip of Africa, impose themselves through the Indian Ocean, and eventually reach Japan in the 1540s. They would create accurate maps of West Africa as far as Sierra Leone, as well as rely on Fra Mauro’s new maps, one of which (1457) mapped the totality of the Old World with unmatched accuracy while suggesting, for the first time, a route around the southern tip of Africa. A mere two years after Diaz had sailed around the Cape; Henricus Martellus created his World Map of 1490, which showed both the whole of Africa generally and the specific locations of numerous places across the entire African west coast, detailing the step-by-step advancement of the Portuguese.

The question of what motivated the expeditions of the Portuguese is a classic one, and, conversely, so is the question of why China abandoned the maritime explorations started by Zheng He. Why were his expeditions not as consequential historically as the ones initiated by Henry the Navigator? For Felipe Fernández-Armesto, Zheng He’s voyages were displays of “China’s ability to mount expeditions of crushing strength and dispatch them over vast distances.” Zheng He’s expeditions did not last and were less consequential, according to Fernández-Armesto, because China’s Confucian government assigned priority to “good government at home” rather than “costly adventures” abroad, particularly in the face of barbarian incursions from the north.20

At the same time, Fernández-Armesto portrays China’s mode of exploration in rather admiring terms: her peaceful commerce, scholarship, and even “vital contributions to the economies of every place they settled.’21He almost implies, indeed, that the Chinese, not the Europeans, were the true explorers, on the grounds that He’s expeditions along the Indian Ocean were more difficult (due to wind patterns) than the European ones through the Atlantic, and that the Europeans navigated through the Atlantic in order to overcome their marginalized economic position rather than to explore.

The major flaw in Fernández-Armesto’s account (as in all current accounts) is the unquestioned assumption that the Chinese expeditions were “explorations” stirred by disinterested curiosity while the Portuguese expeditions were primarily economic in motivation. The Chinese did little that can be considered new in the exploratory sense; they did not discover one single nautical mile; the Indian Ocean had long been a place of regular navigation, unlike the Atlantic and the western coasts of Africa. The Portuguese, it is true, were poor and many of the sailors manning the ships were longing for better opportunities, but what drove the leading men above all else was a chivalric desire for renown and superior achievement in the face of economic costs, persistent hardships, and high mortality rates.

The Chinese were ahead of Europe in technology when the 1400s started, but their technology thereafter remained for the most part unchanged; whereas the Portuguese (and Europeans) would advance continuously. Furthermore, the nautical problems the Portuguese had to face were more difficult. As Joseph Needham has noted,

Almost as far as Madagascar the Chinese were in the realms of the monsoons, with which they had been familiar in their own home waters for more than a millennium. But the inhospitable Atlantic had never encouraged sailors in the same way, and though there had been a number of attempts to sail westwards, that ocean had never been systematically explored.22

The main motivations of the Portuguese cannot be adequately explained without considering the chivalric and warlike spirit of the aristocratic fidalgos. Fernández-Armesto acknowledges that the ethos of chivalric honor “did make the region peculiarly conducive to breeding explorers.”23 But to him this was an ethos rooted in medieval romances exclusive to Portugal and Spain. Besides, he rejects any notion of Western uniqueness, and does not properly explain the differences between economic, religious, and chivalric motivations.

As I see it, the chivalric motivations of the Portuguese colored and intensified all their other motivations, and this is why they exhibited an excessive yearning for spices, a crusading zeal against non-Christians, a relentless determination to master the seas. The chivalry of the Portuguese was a knightly variation of the same Faustian longing the West has displayed since prehistoric times. The ancient Greeks who established colonies throughout the Mediterranean, the Macedonians who marched to “the ends of the world,” the Romans who created the greatest empire in history, the Franks who carved out Charlemagne’s Empire, and the Portuguese, were all similarly driven by an “irrepressible urge to distance.”

NO SOONER DID Columbus sight the “West Indies” in 1492, than one European explorer after another came forth eager for great deeds. By the 1520s, Europeans had explored the entire eastern coast of the two Americas from Labrador to Rio de la Plata. From 1519 to 1522 Ferdinand Magellan led the first successful attempt to circumnavigate the earth through the unimagined vastness of the Pacific Ocean. It has been said that Magellan’s energy and vision equaled that of Columbus; he “shared with his great predecessor the tenacity of a man driven by something deeper than common ambition.’24

Between 1519 and 1521 Hernán Cortés put himself at the command of an expedition that would result in the conquest of the Aztec Empire. These days many regard Cortés as something of a criminal, and this is true. The campaigns he conducted against the Mexicans were graphically barbaric. At the same time, Cortés was a prototypical Western aristocrat, or, as described by his secretary, a man “restless, haughty, mischievous, and given to quarrelling.’25 The running story on Cortés today is that if he had not conquered Mexico someone else would have. The real agents were the guns, the steel swords, the horses, and the germs. Without denying any of these factors, I agree with Buddy Levy’s recent portrayal of Cortés as a man who displayed, again and again, an extraordinary combination of leadership, tenacity, diplomacy, and tactical skill. Finding gold was a priority for Cortés and his men, but, as Cortés’s impassioned speeches and the character descriptions of his contemporaries both testify, he was above all a man driven by an “insatiable thirst for glory and authority;” “he thinks nothing of dying himself, and less of our death.”26 A similar account can be given of Francisco Pizarro.

The same spirit that drove Cortés and Pizarro drove Luther in his uncompromising challenge to the papacy’s authority: “Here I stand, I cannot do otherwise.” It drove the “intense rivalry” that characterized the art of the Renaissance, among patrons, collectors, artists, and that culminated in the persons of Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo, and Titian.27 It motivated Shakespeare to outdo Chaucer, creating more than 120 characters, “the most memorable personalities that have graced the theater – and the psyche – of the West.’28 Let us recall that the age of the conquistadores was Spain’s golden age; the age of El Greco, Velázquez, Calderón de la Barca, and Francisco López de Gómara; the time of Cervantes’s Don Quixote and the realist transformation of the chivalrous imagination, of Lope de Vega and the creation of a new literary style in the picaresque novel with its sympathetic story of thieves and vagabonds. This century saw, additionally, a veritable revolution in cartography. As early as 1507, the German cosmographer, Martin Waldseemüller, produced a map depicting a coastline from Newfoundland to Argentina, and showed the two American continents clearly separated from Asia.

IN THE FACE of a list of rather ordinary human motivations, such as the motivation to acquire wealth and conquer new lands, it is very difficult to ascertain the Faustian character of the explorers, extract its essential nature, and apprehend it for itself. I want to suggest, even so, that the history of exploration during and after the Enlightenment era offers us an opportunity to apprehend clearly this soul. For it is the case that, from about the 1700s onward, explorers come to be increasingly driven by a will to discover irrespective of the pursuit of trade, religious conversion, or even scientific curiosity. My point is not that the unadulterated desire to explore exhibits the Faustian soul as such. The urge to accumulate wealth and advance knowledge may exhibit this Faustian will just as intensively. The difference is that in the desire to explore for its own sake we can see the West’s psyche striving to surpass the mundane preoccupations of ordinary life, comfort and liberal pleasantries, proving what it means to be a man of noble character.

The minimization of any substantial differences among humans cultivated by the modern model of human nature has clouded our ability to apprehend this Faustian desire. The original outlook of Locke and French Enlightenment thinkers, themselves the product of the persistent Western quest to interpret the world anew, fostered a democratic model wherein humans came to be seen as indeterminate and more or less equal, a “white paper,” a malleable being determined by outside circumstances, tradition-less and culture-less. This egalitarian view was nurtured as well in the philosophy of Descartes, Leibnitz, and Kant, with its emphasis on the innate and equally a priori cognitive capacities of humans qua humans.

It should come as no surprise, then, that historians (and psychologists) write of human passions and motivations as essentially alike across all cultures. In our subject of inquiry, exploration, we are normally told that “the desire to penetrate and explore the world’s wild places is a fundamental human impulse.” Frank Debenham’s Discovery and Exploration, a broad survey published in 1960, informs us that “man’s natural inquisitiveness has been a mainspring of discovery and exploration.”29 Yet, much of Debenham’s book is about modern Europeans exploring the world. There is an appendix that lists a total of 203 famous explorers, of which only eight are non-Western.30

Likewise, Fernández-Armesto’s book Pathfinders is described as “a study of humankind’s restless spirit,” but once he reaches the period after the 1500s, he has no explorers outside the West to write about. This may explain why he becomes disparaging toward European explorers, particularly those who came after the 1700s, describing them (David Livingstone, Henry Morton Stanley, Roald Amundsen, and others) as “failures,” “naïve,” “bombastic,” “mendacious,” “useless,” and “incompetent.”31

Likewise, Fernández-Armesto’s book Pathfinders is described as “a study of humankind’s restless spirit,” but once he reaches the period after the 1500s, he has no explorers outside the West to write about. This may explain why he becomes disparaging toward European explorers, particularly those who came after the 1700s, describing them (David Livingstone, Henry Morton Stanley, Roald Amundsen, and others) as “failures,” “naïve,” “bombastic,” “mendacious,” “useless,” and “incompetent.”31

My view is the opposite: the history of exploration provides us with a profoundly revealing index of Western heroic self-fashioning. There is much to be learned about the uniqueness of the West in the life experiences and the motivations driving such men as Captain Cook. During the course of his legendary three Pacific journeys between 1768 and 1779, it is said that he explored more of the earth’s surface than any other man in history. His methods were said to be “practical and humane,” and yet he was also a heroic figure, filled with a zeal for greatness. In his own words, what he wanted above all else was the “pleasure of being first;” to sail “not only farther than man has been before me but as far as I think it possible for man to go.”32

Fernández-Armesto is highly critical of Robert Falcon Scott’s somber expressions of boldness, risk, duty, and resolve during the last days of his tragic expedition to the South Pole in 1911-12. Max Jones offers a far more incisive assessment of the significance of Scott, less as a “great” explorer than as someone who “composed the most haunting journal in the history of exploration.’33 Jones extols the captivating drama of the journals, the mounting tension and ever present anxiety as the ship battles to reach the Antarctica coast, and the epic-like account of the relentless march to the Pole. Jones situates Scott within a wider cultural setting: his immersion in polar literature, his awareness of characters in major novels who sought to prove themselves, his copy of Darwin’s Origins of Species and Scott’s “bleak vision of the universe as a struggle for existence,” the literary influences of Ibsen and Thomas Hardy and their fascination with the dependency of the human will on the indifferent power of nature and necessity.

Overall, the pervading idea of the journals is the heroic vision of exploration as a test of individual worthiness and national character. From his early manhood, Scott was filled with anxiety and doubts about his adequacy in life’s struggles: “I write of the future; of the hopes of being more worthy; but shall I ever be – can I alone, poor weak wretch that I am bear up against it all.”34 Expedition narratives through the nineteenth century, Jones observes, became ever more focus on the character of the explorer than on the economic externalities, so exploration became an inner journey, “a journey into the self, nowhere more so than in the emptiest of continents, Antarctica.’35 Scott understood this: “Here the outward show is nothing; it is the inward purpose that counts.” There was nothing to see in the center of Antarctica except the reflection of the inner Western quest to face the struggle of life in a heroic fashion.

♦

Ricardo Duchesne is professor at the University of New Brunswick, Department of Social Science, Saint John, Canada. He is the author of The Uniqueness of Western Civilization (2011). [US Amazon link.]

This article was revised 8 October 2012 to correct an editing error.

NOTES:

- Judith Shulevitz, “‘Human Accomplishment:’ the Best and the Brightest,” The New York Times, 30 November 2003. ↩

- Charles Murray, Human Accomplishment, The Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts and Sciences 800 BC to 1950 (New York: HarperCollins Publishing Inc, 2003), 252-259. ↩

- David Gress, From Plato to NATO, The Idea of the West and Its Opponents (The Free Press, 1996). ↩

- Norman Davies, A History of Europe (New York: Random House, 1997), 28. ↩

- Davies, 15-16. ↩

- Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West: I: Form and Actuality, translated by Charles Francis Atkinson (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1973), 183-216. ↩

- John Farrenkopf, Prophet of Decline: Spengler on World History and Politics (Louisiana State University Press, 2001), 46. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- G.W.F. Hegel, Philosophy of Mind. Being Part Three of the Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences, translated by William Wallace (Oxford University Press, 1971), 45. ↩

- A.G. Woodhead, The Greeks in the West (New York: Praeger, 1966), 32-33. Robin Lane Fox’s Travelling Heroes: Greeks and The Epic Age of Homer (Allen Lane, 2008), deals with how their travels from one end of their world to the other shaped the Greeks’ myth, heroes, and gods. ↩

- For an up-to-date review of the Greek explorations of the Atlantic world, including a chapter on Roman expeditions to the North Sea, see Duane Roller’s Through the Pillars of Herakles: Greco-Roman Exploration of the Atlantic (Routledge, 2006). ↩

- Rome is not known to have carried as many explorations as the Greeks; still, it should be noted that the Romans penetrated deeper into Africa than any European power until well into the nineteenth century; see L. P Kirwan, “Rome Beyond The Southern Egyptian Frontier,” The Geographical Journal, (123.1: 1957). ↩

- Decline of the West, 332. ↩

- Jesse Byock, Viking Age Iceland (Penguin Books, 2001). ↩

- Peter Whitfield, New Found Lands. Maps in the History of Exploration (New York: Routledge, 1998), 18. ↩

- The Vinland Sagas, The Norse Discovery of America, translated with an introduction by Magnus Magnusson and Hermann Palsson (Penguin Books, 1965). ↩

- Daniel Boorstin, The Discoverers (Vintage Books, 1985), 121. ↩

- John Larner, Marco Polo and the Discovery of the World (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999). ↩

- Decline of the West, 333. ↩

- Pathfinders, A Global History (New York: Norton, 2006), 109-117. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Joseph Needham, The Shorter Science and Civilization in China, Volume 3: A Section of Volume IV, Part I and a Section of Volume IV, Part 3 of Needham’s Original Text (Cambridge University Press, 1995), 141. ↩

- Pathfinders, 145. ↩

- Whitfield, 93. ↩

- Buddy Levy, Conquistador, Hernan Cortes, King Montezuma, and the Last Stand of the Aztecs (Bantam Books, 2009), 3. ↩

- Levy, 203. ↩

- See Rona Goffe’s, Renaissance Rivals (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), for an account of the passionate strivings of the greatest artists of the Renaissance to outdo both living competitors and the masters of antiquity. ↩

- Frank Dumont, A History of Personality Psychology (Cambridge University Press, 2010), 20. ↩

- Frank Debenham, Discovery and Exploration (London: Paul Hamlyn, 1960), 6. ↩

- The same line of reasoning occupies Piers Pennington’s The Great Explorers (London: Aldus Books, 1979): “this book tells the story of the world’s great adventures into the unknown,” yet the fifty-plus explorers listed are from the Occident. See also The Discoverers: An Encyclopedia of Explorers and Exploration, ed. Helen Delpar (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1980). ↩

- Pathfinders, 394. ↩

- Cited in Hanbury-Tenison, ed., The Oxford Book of Exploration (Oxford University Press, 1993), 490-3. This book is an anthology of writings by explorers. ↩

- Max Jones, “Introduction” in Robert Falcon Scott’s Journals: Captain Scott’s Last Expedition (Oxford University Press), xvii. ↩

- Ibid., xix. ↩

- Ibid, xxxiv-xxxv. ↩

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Apollinische antieke wiskunde

Apollinische antieke wiskunde

But I believe that the Industrial Revolution, including developments leading to this Revolution, barely capture what was unique about Western culture. I am obviously aware that other cultures were unique in having their own customs, languages, beliefs and historical experiences. My claim is that the West was uniquely exceptional in exhibiting in a continuous way the greatest degree of creativity, novelties, and expansionary dynamic. I trace the uniqueness of the West back to the aristocratic warlike culture of

But I believe that the Industrial Revolution, including developments leading to this Revolution, barely capture what was unique about Western culture. I am obviously aware that other cultures were unique in having their own customs, languages, beliefs and historical experiences. My claim is that the West was uniquely exceptional in exhibiting in a continuous way the greatest degree of creativity, novelties, and expansionary dynamic. I trace the uniqueness of the West back to the aristocratic warlike culture of

What was the ultimate original ground of the West’s Faustian soul? There are statements in Spengler which make references to “a Nordic world stretching from England to Japan” and a “harder-struggling” people, and a more individualistic and heroic spirit “in the old, genuine parts of the Mahabharata . . . in Homer, Pindar, and Aeschylus, in the Germanic epic poetry and in Shakespeare, in many songs of the Chinese Shuking, and in circles of the Japanese samurai” (as cited in Farrenkopf: 227). Spengler makes reference to the common location of these peoples in the “Nordic” steppes. He does not make any specific reference to the Caucasian steppes but he clearly has in mind the “Aryan Indian” peoples who came out of the steppes and conquered India and wrote the Mahabharata. He calls “half Nordic” the Graeco-Roman, Aryan Indian, and Chinese high cultures. In Man and Technics, he writes of how the Nordic climate forged a man filled with vitality

What was the ultimate original ground of the West’s Faustian soul? There are statements in Spengler which make references to “a Nordic world stretching from England to Japan” and a “harder-struggling” people, and a more individualistic and heroic spirit “in the old, genuine parts of the Mahabharata . . . in Homer, Pindar, and Aeschylus, in the Germanic epic poetry and in Shakespeare, in many songs of the Chinese Shuking, and in circles of the Japanese samurai” (as cited in Farrenkopf: 227). Spengler makes reference to the common location of these peoples in the “Nordic” steppes. He does not make any specific reference to the Caucasian steppes but he clearly has in mind the “Aryan Indian” peoples who came out of the steppes and conquered India and wrote the Mahabharata. He calls “half Nordic” the Graeco-Roman, Aryan Indian, and Chinese high cultures. In Man and Technics, he writes of how the Nordic climate forged a man filled with vitality There can no development of the human faculties, no high culture, without conflict, aggression, and pride. It is these asocial traits, “vainglory,” “lust for power,” “avarice,” which awaken the otherwise dormant talents of humans and “drive them to new exertions of their forces and thus to the manifold development of their capacities.” Nature in her wisdom, “not the hand of an evil spirit,” created “the unsocial sociability of humans.”

There can no development of the human faculties, no high culture, without conflict, aggression, and pride. It is these asocial traits, “vainglory,” “lust for power,” “avarice,” which awaken the otherwise dormant talents of humans and “drive them to new exertions of their forces and thus to the manifold development of their capacities.” Nature in her wisdom, “not the hand of an evil spirit,” created “the unsocial sociability of humans.” But how do we connect the barbaric asocial traits of prehistoric Indo-European warriors to the superlative cultural achievements of Greeks and later civilized Europeans? Nietzsche provides us some keen insights as to how the untamed agonistic ethos of Indo-Europeans was translated into civilized creativity. In his fascinating early essay, “Homer on Competition” (1872), Nietzsche observes that civilized culture or convention (nomos) was not imposed on nature but was a sublimated continuation of the strife that was already inherent to nature (physis). The nature of existence is based on conflict and this conflict unfolded itself in human institutions and governments. Humans are not naturally harmonious and rational as Socrates had insisted; the nature of humanity is strife. Without strife there is no cultural development. Nietzsche argued against the separation of man/culture from nature: the cultural creations of humanity are expressions or aspects of nature itself.

But how do we connect the barbaric asocial traits of prehistoric Indo-European warriors to the superlative cultural achievements of Greeks and later civilized Europeans? Nietzsche provides us some keen insights as to how the untamed agonistic ethos of Indo-Europeans was translated into civilized creativity. In his fascinating early essay, “Homer on Competition” (1872), Nietzsche observes that civilized culture or convention (nomos) was not imposed on nature but was a sublimated continuation of the strife that was already inherent to nature (physis). The nature of existence is based on conflict and this conflict unfolded itself in human institutions and governments. Humans are not naturally harmonious and rational as Socrates had insisted; the nature of humanity is strife. Without strife there is no cultural development. Nietzsche argued against the separation of man/culture from nature: the cultural creations of humanity are expressions or aspects of nature itself. This agonistic ethos was ingrained in the Olympic Games, in the perpetual warring of the city-states, in the pursuit of a political career and in the competition among orators for the admiration of the citizens, and in the Athenian theater festivals where a great many poets would take part in Dionysian competitions. It was evident in the sophistic-Socratic ethos of dialogic argument and the pursuit of knowledge by comparing and criticizing individual speeches, evaluating contradictory claims, collecting out evidence, competitive persuasion and refutation. And in the Catholic scholastic method, according to which critics would engage major works, read them thoroughly, compare the book’s theories to other authorities, and through a series of dialogical exercises ascertain the respective merits and demerits.

This agonistic ethos was ingrained in the Olympic Games, in the perpetual warring of the city-states, in the pursuit of a political career and in the competition among orators for the admiration of the citizens, and in the Athenian theater festivals where a great many poets would take part in Dionysian competitions. It was evident in the sophistic-Socratic ethos of dialogic argument and the pursuit of knowledge by comparing and criticizing individual speeches, evaluating contradictory claims, collecting out evidence, competitive persuasion and refutation. And in the Catholic scholastic method, according to which critics would engage major works, read them thoroughly, compare the book’s theories to other authorities, and through a series of dialogical exercises ascertain the respective merits and demerits. If I had to choose one word to explain why the West has been the most creative civilization it would be “Faustian.” My choice of this word hinges on the realization that the West has been following a unique cultural path since ancient times in the course of which it has exhibited far higher levels of achievement in all the intellectual, artistic, and heroic spheres of life.

If I had to choose one word to explain why the West has been the most creative civilization it would be “Faustian.” My choice of this word hinges on the realization that the West has been following a unique cultural path since ancient times in the course of which it has exhibited far higher levels of achievement in all the intellectual, artistic, and heroic spheres of life. We need an explanation for this incredible discrepancy. But what exactly is the Faustian soul? How do we connect it to Europe’s creativity? To what original source or starting place did Spengler attribute this yearning for infinity? He directed attention to the barbarian peoples of northern Europe. In Man and Technics, he wrote of how the Nordic climate forged a character filled with vitality, “an intellect sharpened to the most extreme degree, with the cold fervour of an irrepressible passion for struggling, daring, driving forward.” The Nordic character was a human biological being to be sure, but one animated with the spirit of a “proud beast of prey,” like that of an “eagle, lion, [or] tiger.” For this Nordic individual, “the concerns of life, the deed, became more important than mere physical existence.” He wants to climb high, soar upward and reach ever higher levels of existential intensity. Adaptation and reproduction are not enough (Man and Technics: A Contribution to a Philosophy of Life, Greenwood Press, 1976: 19-41).

We need an explanation for this incredible discrepancy. But what exactly is the Faustian soul? How do we connect it to Europe’s creativity? To what original source or starting place did Spengler attribute this yearning for infinity? He directed attention to the barbarian peoples of northern Europe. In Man and Technics, he wrote of how the Nordic climate forged a character filled with vitality, “an intellect sharpened to the most extreme degree, with the cold fervour of an irrepressible passion for struggling, daring, driving forward.” The Nordic character was a human biological being to be sure, but one animated with the spirit of a “proud beast of prey,” like that of an “eagle, lion, [or] tiger.” For this Nordic individual, “the concerns of life, the deed, became more important than mere physical existence.” He wants to climb high, soar upward and reach ever higher levels of existential intensity. Adaptation and reproduction are not enough (Man and Technics: A Contribution to a Philosophy of Life, Greenwood Press, 1976: 19-41).