Martial Roudier, vous étiez présent dans le cortège de la manifestation occitaniste du 24 octobre à Montpellier, que faut-il en retenir une fois les clameurs retombées?

Cette manifestation « pour la langue occitane » s’inscrivait dans un cadre plus global de revendications linguistiques des différents peuples minorisés de France. Ces manifestations ont lieu de façon régulière sur notre territoire puisque la question linguistique en France est dans une impasse depuis de (trop) nombreuses années. Ainsi la dernière manifestation de Toulouse en 2012 avait réuni aux alentours de 30 000 participants.

Cette manifestation « pour la langue occitane » s’inscrivait dans un cadre plus global de revendications linguistiques des différents peuples minorisés de France. Ces manifestations ont lieu de façon régulière sur notre territoire puisque la question linguistique en France est dans une impasse depuis de (trop) nombreuses années. Ainsi la dernière manifestation de Toulouse en 2012 avait réuni aux alentours de 30 000 participants.

Ceux qui ont arpenté les rues de Montpellier samedi dernier n’ont pu que constater la maigreur des effectifs rassemblés. Les organisateurs attendaient les 30 000 participants de la session précédente mais hélas ce fut moins de la moitié, voire beaucoup moins, qui a défilé. Sans entrer dans la guéguerre des chiffres -4000 selon la police/15000 selon les organisateurs-, le Midi Libre, plutôt favorable à la manifestation, annonce 6 000 participants… Même si on atteint les 10 000 participants, la mobilisation peut être qualifiée de médiocre. Pas uniquement numériquement parlant, mais symboliquement. Il faut remettre en contexte ces manifestations linguistico-revendicatives dans un cadre international et plus précisément dans le cadre européen qui réunit des composantes socio-économiques similaires. Prenons exemple, et c’est l’objectif que devraient se fixer les fameux « occitanistes » les soi-disant défenseurs de l’identité occitane, prenons exemple donc sur ces deux petits peuples (numériquement parlant) que sont le peuple écossais et notre voisin, notre cousin le peuple catalan. 5 millions et 7 millions et demi de personnes qui poussent le processus d’auto-détermination depuis de longues années. Avec le succès heureux que nous connaissons… Contrairement à nous il faut oser le dire.

N’avez-vous pas l’impression qu’au-delà de la défense de la langue, les organisateurs et le « premier cercle » mettent plus en avant des revendications corporatistes que franchement identitaires.

Le terme de « corporatisme » est parfaitement choisi. Les revendications confèrent souvent à une schizophrénie politique et entretiennent en tous cas la confusion chez les identitaires de cœur. Prenons comme exemple la défiance, voire le rejet de tout ce qui touche à l’idée de Nation et aux frontières qui lui sont consubstantielles. La problématique de base réside dans la définition même de ce qu’être occitan signifie. Dès lors que vous rejetez d’emblée les notions d’identité, de peuple, de nation, d’histoire même -thèmes dont se défient les « occitanistes »-, sur quel socle va s’appuyer votre combat ?

Ainsi les revendications portées par les manifestations occitanistes tournent toutes autour de négociations avec l’éducation nationale. Comme si grapiller quelques places de prof à l’IUFM allaient générer des locuteurs injustement privés de leur langue? Il est de coutume également d’entendre lors de certaines festivités à coloration occitane, festivités qui ressemblent à s’y méprendre à la fête de l’Huma, que l’occitanité est un choix. Comme argument plus inorganique, il n’y a pas mieux. Il est vrai qu’en tant que défenseur chez soi d’une culture minorisée, une certaine attirance vers des modes de vie alternatifs est absolument naturelle : le bio (le vrai, pas le commercial), les modes de vie en sociétés parallèles, les médecines alternatives, les quêtes spirituelles, la remise en question permanente des modes de consommation et j’en passe; mais il n’empêche qu’être d’un peuple c’est avant tout un héritage multi séculaire qui s’est forgé dans la terre et dans le sang. Le reste, à de très rares exceptions près, n’est que délire de consommateur de chanvre.

Sur une banderole d’un groupe d’étudiants de l’Université Paul Valéry, on pouvait lire : « Pas de frontièras, pas de nacions, pas de discriminacions » au-delà de la provocation de potache, sur quoi repose alors la revendication occitaniste ?

Tout simplement sur le fait de parler ou non la langue d’oc ou à la rigueur, l’une de ses variantes (gasconne, provençale…) Ce dernier point ne faisant pas l’unanimité à cause du jacobinisme languedocien de l’IEO et des structures affiliées. La question de l’usage de la langue est une bonne chose en soi mais le problème réside dans le fait que ce concept est malheureusement périmé. Lorsque tout le peuple résidant dans les pays d’Oc est « occitanophone », la langue est d’évidence le premier paramètre qui définit ce peuple mais lorsque ce même peuple est privé d’expression par le biais de réformes successives et d’une éducation nationale qui n’est pas de la même langue, cette dernière devient une exception. Mais le peuple lui, est toujours présent sur son sol! Il faut apporter un bémol à ce postulat et parler également du problème de l’immigration. Encore un énorme tabou chez les dirigeants du mouvement occitan. L’immigration, quand elle revêt des proportions démesurées, déstructure les fondements d’un peuple dans son essence même. D’un point de vue culturel, psychique, physique, la nature même des peuples peuvent changer. Rarement dans le bon sens malheureusement… Quand on parle des conséquences néfastes de l’immigration, on pense évidemment à l’immigration maghrébine mais il faut également prendre en compte l’immigration interne au territoire national français et à l’Europe. Car nous sommes devenus le coin de terre où l’on vient finir ses vieux jours au soleil, voire y toucher son RSA… tranquille pépère. Une maison de retraite doublée d’un pôle emploi!

Vous semblez n’avoir pas une grande estime pour la méthode qui inspire les organisateurs de cette manifestation… avez-vous d’autres reproches à leur faire ?

D’autres travers plombent la revendication occitane. Ils sont nombreux mais certains sont des freins structurels colossaux intrinsèques à l’organisation du milieu « occitaniste ». Le cursus scolaire de la maternelle à la faculté ressemble à l’usine de cadres formatés idéologiquement dont les dictatures communistes ont le secret. Tous les responsables politiques culturels et associatifs sont de gôche, d’ailleurs ils le revendiquent. Qui chez les Verts, qui chez les socialos, qui plutôt anar, telle professeure de fac carrément marxiste… N’oublions pas la collusion entre les partis de gauche nationaux et leurs homologues sudistes… Clientélisme et occitanisme font bon ménage. Et puis les cultureux doivent bien gameller eux aussi, il ne faut donc pas mordre la main qui nourrit tout ce petit monde.

On voit le résultat sur la scène culturelle occitane: 2 pauvres groupes de musique qui se battent en duel, une quasi inexistence de production littéraire. L’absence de visibilité dans la sphère publique en est directement la conséquence. Nous assistons à une professionnalisation de la chose culturelle. Une réserve folklorique à ciel ouvert. Une mise sous perfusion bien orchestrée par Paris mais avec l’assentiment pervers d’une classe dirigeante locale. Le peuple lui, pendant ce temps là, s’acculture complètement et ne sait plus d’où il vient. Parfait petit pion mondialisé sans racines ni rêves. Car, pour citer Mistral, sans la langue, pas de clef.

Pour remonter la pente quelle est la première mesure que doit prendre le « mouvement occitaniste » ?

Les dirigeants du mouvement occitaniste sont issus d’une caste très fermée dont le terreau culturel politique se situe dans la pire des extrêmes gauches françaises qui se renouvelle filialement.

Les penseurs et donc ceux qui impriment la direction du mouvement sont, pour la plupart, issus du corps professoral et par conséquent touchent leur salaire directement de l’Etat français, auxquels ils devraient en principe s’opposer. On assiste donc à un jeu de dupes où ce sont les amoureux de la culture occitane qui se retrouvent cocus. Comme un ouvrier qui délègue sa défense à un syndicat chargé de lutter à sa place contre le méchant patron. On sait très bien que les collusions syndicat/patronat sont bien rodées…

Pour tout ceci et pour tant d’autres choses encore, il apparaît nécessaire de « décapiter » la direction du mouvement occitaniste et de la remplacer par de vrais acteurs de la vie locale, eux, sincères patriotes. Il est peut être encore temps…

Photos : Lengadoc Info

Lengadoc-info.com, 2015, dépêches libres de copie et diffusion sous réserve de mention de la source d’origine.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

The hatred of the ‘West’ and of ‘Europe’ is the hatred for a Civilisation that had already reached an advanced state of decay into materialism and sought to impose its primacy by cultural subversion rather than by combat, with its City-based and money-based outlook, ‘poisoning the unborn culture in the womb of the land’. (Spengler, 1971, II, 194). Russia was still a land where there were no bourgeoisie and no true class system but only lord and peasant, a view confirmed by Berdyaev, writing:

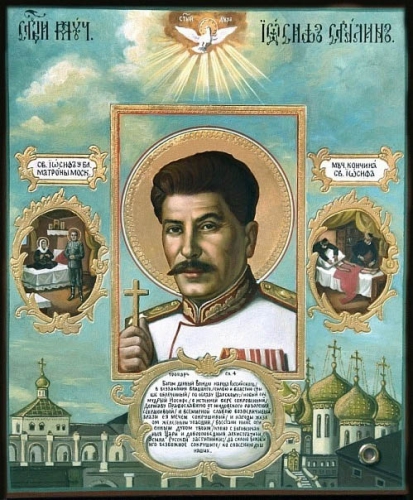

The hatred of the ‘West’ and of ‘Europe’ is the hatred for a Civilisation that had already reached an advanced state of decay into materialism and sought to impose its primacy by cultural subversion rather than by combat, with its City-based and money-based outlook, ‘poisoning the unborn culture in the womb of the land’. (Spengler, 1971, II, 194). Russia was still a land where there were no bourgeoisie and no true class system but only lord and peasant, a view confirmed by Berdyaev, writing:  Spengler states above that the Russians do not ‘fight’ capital. (Ibid., 495). Yet their young soul brings them into conflict with money, as both oligarchy from inside and plutocracy from outside contend with the Russian soul for supremacy. It was something observed by both Gogol and Dostoyevski. The anti-capitalism and ‘world revolution’ of Stalinism took on features that were drawn more from Russian messianism than from Marxism, reflected in the struggle between Trotsky and Stalin. The revival of the Czarist and Orthodox icons, martyrs and heroes and of Russian folk-culture in conjunction with a campaign against ‘ rootless cosmopolitanism’, reflected the emergence of primal Russian soul amidst Petrine Marxism. (Brandenberger, 2002). Today the conflict between two world-views can be seen in the conflicts between Putin and certain ‘oligarchs’ and the uneasiness Putin causes among the West.

Spengler states above that the Russians do not ‘fight’ capital. (Ibid., 495). Yet their young soul brings them into conflict with money, as both oligarchy from inside and plutocracy from outside contend with the Russian soul for supremacy. It was something observed by both Gogol and Dostoyevski. The anti-capitalism and ‘world revolution’ of Stalinism took on features that were drawn more from Russian messianism than from Marxism, reflected in the struggle between Trotsky and Stalin. The revival of the Czarist and Orthodox icons, martyrs and heroes and of Russian folk-culture in conjunction with a campaign against ‘ rootless cosmopolitanism’, reflected the emergence of primal Russian soul amidst Petrine Marxism. (Brandenberger, 2002). Today the conflict between two world-views can be seen in the conflicts between Putin and certain ‘oligarchs’ and the uneasiness Putin causes among the West.

Erdogan était jusqu'ici apparu aux yeux de nombreux observateurs comme un personnage vaniteux et autoritaire, tenté par le rêve de réincarner à lui seul l'antique Empire Ottoman, un personnage finalement maladroit.

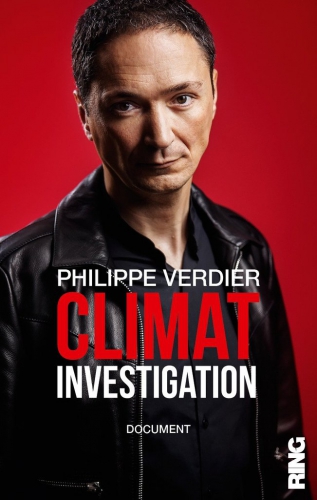

Erdogan était jusqu'ici apparu aux yeux de nombreux observateurs comme un personnage vaniteux et autoritaire, tenté par le rêve de réincarner à lui seul l'antique Empire Ottoman, un personnage finalement maladroit. Le réchauffement climatique vient de faire une nouvelle victime, Philippe Verdier. Chef du Service Météo de France 2 depuis septembre 2012, il vient d'être licencié par la chaîne de télévision qui l'avait suspendu d'antenne auparavant. Il en a fait l'annonce vidéo, symboliquement, le jour de la fête de la Toussaint...

Le réchauffement climatique vient de faire une nouvelle victime, Philippe Verdier. Chef du Service Météo de France 2 depuis septembre 2012, il vient d'être licencié par la chaîne de télévision qui l'avait suspendu d'antenne auparavant. Il en a fait l'annonce vidéo, symboliquement, le jour de la fête de la Toussaint...

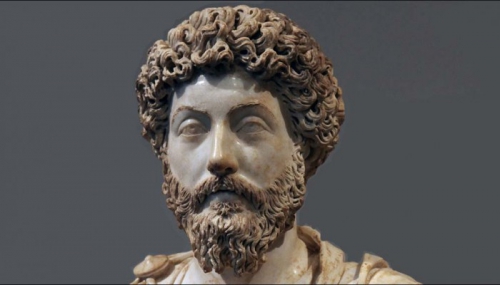

This is pretty good, as denunciations of Stoicism go, seductive in its articulateness and energy, and therefore effective, however uninformed.

This is pretty good, as denunciations of Stoicism go, seductive in its articulateness and energy, and therefore effective, however uninformed.