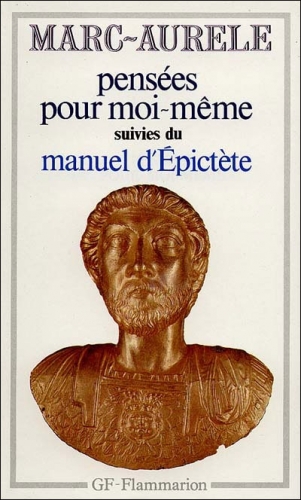

The Meditations [2] of Marcus Aurelius are a remarkable spiritual diary and, in general, a sure way for the modern reader to imbue himself with the practical wisdom of our ancient forefathers [3]. That said, I do not believe we should uncritically defer to anything, and on two points in particular, I believe comment and criticism are warranted.

Firstly, a pervasive theme of Marcus’ is his struggle to control his judgment and emotions, in particular anger, and thus be as detached and “philosophical” as possible. The goal is to accept non-judgmentally all that Nature — which is the law of the universe — gives us and to ensure harmony with the world and the rule of reason within oneself.

Marcus makes these comments particularly with regard to his colleagues and subordinates: do not get angry with their inevitable failures and ignorance, he tells himself, but rather try to make them see the light:

How cruel it is not to let people strive after what they regard as suitable and beneficial to themselves. And yet, in a sense, you are not permitting them to do so whenever you grow angry at their bad behavior. For it is surely the case that they are simply drawn towards what they consider to be suitable and beneficial to themselves. “Yes, but they are wrong to think that.” Well, instruct them, then, and show them the truth, without becoming annoyed. (6, 27) (Numbering refers to the book and paragraph in the Meditations.)

And elsewhere: “Even if you burst with rage, they will do the same things none the less for that” (8, 4). More generally, Marcus affirms that “an intelligence free from passions is a mighty citadel” (8, 48).

And elsewhere: “Even if you burst with rage, they will do the same things none the less for that” (8, 4). More generally, Marcus affirms that “an intelligence free from passions is a mighty citadel” (8, 48).

The potential problem in these affirmations is that one might be led to believe that Marcus is suggesting becoming a kind of harmless, emotionless monk. However, I believe these comments should not be misunderstood. Marcus does affirm that, when push comes to shove, coercion is justified: “Try to persuade them, but act even against their will the principles of justice demand it” (6, 50).

Marcus honors Diogenes, who was a great philosopher of an evidently very different temperament, for he sought to moralize society by repeatedly shaming and ridiculing the immoral and the ignorant through various shock tactics. Diogenes once reputedly criticized Plato saying: “Of what use is a philosopher who doesn’t hurt anybody’s feelings?’ Marcus’ ostentatiously tranquil way is evidently not the only one available to us.

“Freedom from passions” furthermore must be understood in a wider sense, of one’s reason being invulnerable to not just emotions, but also pleasure and pain. The Romans in particular perfected this with an unbelievable gravitas in the defense of honor and duty: Seneca following Nero’s order to kill himself, in accordance with tradition, by slitting his wrists in a hot bath; Marcus Atilius Regulus who was captured and released by the Carthaginians, urged the Roman Senate to continue the war, and then returned to Carthage to fulfill his parole, where he was tortured to death; or indeed the famous soldier at Pompeii [4] who, having not been relieved, stoically remained at his post until he was buried by the ashes.

These sacrifices may seem futile, but they reflect the supreme manliness of the Roman tradition, a virility which reflected the discipline and sacrifice necessary to maintaining that greatest of world empires. In our age, the Roman example shames us for our cowardice. Marcus’ “mighty citadel” is a model for defending our people and the truth, whatever the personal consequences might be. When we are cowards, we should think of our forefathers, whether religious reformers or scientific innovators, who were willing to risk being burned at the stake to affirm the truth.

Having said all this, perhaps Marcus is too categorical in dismissing emotion. Plato argued that emotions were meant to be the powerful subordinate allies of reason. For example, anger is an emotion propitious to the extermination of one’s enemies. (Then again, Marcus was a fairly effective military commander in his continuous and often brutal campaigns against the Germans. So perhaps I am in no position to talk, but I share my reaction.)

Certainly in both elite and mass politics nothing is possible without the inspiration of emotions, in particular appeal to our deep-seated tribal and spiritual longings. Practically, the fact is that Christianity displaced ancient philosophy and the old Pagan religion by appealing to emotion. The philosopher may protest that this is irrational, but all the same, ancient philosophy died and only lived on in the Middle Ages, to the extent it did, in Christianity, because Christianity could better appeal to that irrational part of us, particularly among the masses.

Marcus writes that one should not aim for “Plato’s ideal state . . . For who can change the convictions of others?” (9, 29) The answer, to the degree men can be socio-culturally programmed and moralized, is of course education and religion. In the ancient world, the ability to do so in a vast realm like the Roman Empire was limited. In the modern era however, fascists have emphatically and convincingly argued that there are enormous possibilities for mass education and civil-religion, especially given the new technological and material means enabling mass communication and mass ceremony.

Secondly, and this is a more critical comment, Marcus’ Meditations are a striking example of pre-Christian universalism in Western thought. As Kevin MacDonald has stressed, both universalist and ethnocentric trends are evident in the Western tradition. While Diogenes declared himself a “cosmopolitan,” Plato’s masterwork The Republic [5] powerfully makes the case for ethnocentric morality [5].

Marcus adheres to Stoic cosmopolitanism, a kind of dual citizenship. He writes: “As [emperor], my city and fatherland is Rome; as a human being, it is the universe; so what brings benefits to these is the sole good for me” (6, 44). He elsewhere defines himself as “a citizen of this great city [the universe]” and argues that one should not be dissatisfied with a short life, playing only a small part in this vast play (12, 36).

I do not believe this is problematic. The laws of Nature are the same for all creatures and, in this sense, all human must seek to be in harmony with them. This is a message which will resonate as much with the Jeffersonian deist as the esoteric National Socialist, and indeed perhaps with almost all of the world’s religions. Since Darwin in particular however, we as evolutionary thinkers understand natural selection and survival of the fittest as fundamental principles and imperatives of life. These principles must be recognized and lived up to if we and indeed any creatures capable of conscious morality and reason are to survive and thrive, for all this, whatever the spiritual beyond, rests upon a biological foundation and genetic prerequisites.

I believe all of this is compatible with ethnocentric morality: solidarity with one’s kin is a natural principle, and Nature expresses herself uniquely in every creature. (What is required of a donkey to be in harmony with the universe is not the same as what is required of a man, and so forth in the infinite diversity of humans and other living creatures.) More generally, the world would in fact be a better place if all societies recognized genetic homogeneity and quality as social goods in and of themselves. While I am no expert on moral philosophy, I do not believe the Kantian moral imperative necessarily undermines nationalism, perhaps the contrary in fact.

More problematic however is the following:

Say to yourself at the start of the day, I shall meet with meddling, ungrateful, violent, treacherous, envious, and unsociable people. They are subject to these defects because they have no knowledge of good and bad. [. . .] [H]is nature is akin to my own — not because he is of the same blood and seed, but because he shares as I do in mind and thus in a portion of the divine. (2, 1)

This comment needs to be understood in the context of Marcus’ attempt to get along with inadequate and unsociable colleagues, arguing that frustration is inevitable but improvement is possible through appeal to a common reason. Elsewhere Marcus is more explicit still: “how close is the kinship which unites each human being to the human race as a whole, for it arises not from blood and seed but from our common share in reason” (12, 26).

The assertion that “his nature is akin to my own – not because he is of the same blood and seed, but because he shares as I do in mind and thus in a portion of the divine” is of course partly true today (all humans have some capacity for reason) and was probably truer still in the Roman Empire of Marcus’ day, which was far less racially diverse than are the United States and even much of Western Europe in our time. (That the Empire had intermingled Europeans and Semites in uneven quantities cannot be compared with societies made up of people from different ends of different continents with no contiguous clinal link at all, e.g. Western Europeans, Sub-Saharan Africans, East Asians . . .).

As evolutionary thinkers however, we are cognizant of the fact that intelligence and personality are significantly heritable [6], and thus they in fact do ultimately stem from “blood and seed.” There is a large body evidence that different racial groups have differing average levels of intelligence (also varying by kind of intelligence, e.g. verbal, spatial . . .) and, more importantly, different average temperaments. Reason is the same for all but in different brains manifests itself in different degrees and is inflected with different motivations.

This has enormous implications for political morality: ethno-genetically heterogeneous societies are disharmonious both because of each ethnic group’s differing preferences and in the lack of identification/solidarity between the groups (the latter made especially problematic when the different groups, inevitably, become socially unequal due to differing behavior). This prevents, in multiethnic societies, the possibility of a collectively rational and solidary cohesive community, which must be the organic unit of human history.

One might answer: reason is the same for all creatures, even if their capacity for it differs. Perhaps if one could strip emotions away, but that would also vary by individual and group. It is obvious that reason manifests itself differently in different groups, who find different things intellectually interesting and emotionally compelling. (For instance, northern Europeans seem prone to a kind of selfless piety, only among sub-Saharan Africans have I observed this quite spontaneous phenomenon [7], and Jews more than any other group seem to get a kick out of criticizing the host population’s real and imagined flaws.)

Put another way: Reason is the same for all? Quite. If so I invite our colored cousins to answer the question: Is the slow bit steady disappearance of the European peoples reasonable? Is this event in the higher interests of the human race and universal consciousness and morality? I observe that in arguing against us, these same people resort to moral principles founded in the West (“international law,” “human rights,” “democracy” . . .) and use Western technology which thus far, only the East Asians have shown any talent for emulating, let alone inventing. Furthermore, innumerable millions of colored people throughout the world are so convinced of their own inability to create a good society that their only plan for improving their lot in life is to . . . move to our societies! And then, I should add, the process repeats itself within countries, with the notorious dialectic between forced integration and white flight. Well, colored cousins, these antics will not work when you run out of white people.

In their heart of hearts, all must know that the disappearance of the Europeans is a supremely immoral act, and some colored people might even be endowed with sufficient reason to overcome their ethnic pride in acknowledging this. And some will come to the conclusion that the defense of ethnic European interests is reasonable and in the universal interest. But only an infinitesimal number, for such is the power of the call of the blood [8].

But all that is none of our business, for you should not “allow your happiness to depend on what passes in the souls of other people” (2, 6). We take our own side. Inspired by the best of our magnificent tradition [9], including the formidable Stoicism of Marcus Aurelius and the other great men of the West whose wisdom and character put us to shame, we must become Eurocentric Hereditarians.

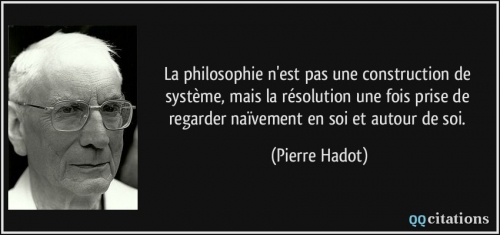

Il existe plusieurs types d’exercices spirituels liés à l’étude de la nature, et donc à la physique. Pour Pierre Hadot, le premier exercice stoïcien qui permet de mettre en pratique la physique stoïcienne, c’est l’exercice qui consiste à « se reconnaître comme partie du Tout, à s’élever à la conscience cosmique, à s’immerger dans la totalité du cosmos » (P. Hadot, 1995, p. 211). C’est

Il existe plusieurs types d’exercices spirituels liés à l’étude de la nature, et donc à la physique. Pour Pierre Hadot, le premier exercice stoïcien qui permet de mettre en pratique la physique stoïcienne, c’est l’exercice qui consiste à « se reconnaître comme partie du Tout, à s’élever à la conscience cosmique, à s’immerger dans la totalité du cosmos » (P. Hadot, 1995, p. 211). C’est

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les guerres se succédèrent, à peine la guerre (161–166) contre les Parthes (Perses) est-elle terminée, que les barbares menacent directement le nord de l’Italie. Il faut plus de cinq années (169–175) à l’empereur pour venir à bout de cette menace. C’est alors qu’une rumeur de la mort de Marc Aurèle conduit Avidius Cassius, gouverneur d’une large partie de l’Orient, à se proclamer empereur. Mais en juillet 175, celui-ci est assassiné et sa tête envoyée à Marc Aurèle. Ce dernier regretta sa mort, sûr de son repentir. Enfin, dès 177, Marc Aurèle doit repartir guerroyer sur la frontière danubienne où il y mourra (180).

Les guerres se succédèrent, à peine la guerre (161–166) contre les Parthes (Perses) est-elle terminée, que les barbares menacent directement le nord de l’Italie. Il faut plus de cinq années (169–175) à l’empereur pour venir à bout de cette menace. C’est alors qu’une rumeur de la mort de Marc Aurèle conduit Avidius Cassius, gouverneur d’une large partie de l’Orient, à se proclamer empereur. Mais en juillet 175, celui-ci est assassiné et sa tête envoyée à Marc Aurèle. Ce dernier regretta sa mort, sûr de son repentir. Enfin, dès 177, Marc Aurèle doit repartir guerroyer sur la frontière danubienne où il y mourra (180).

This is pretty good, as denunciations of Stoicism go, seductive in its articulateness and energy, and therefore effective, however uninformed.

This is pretty good, as denunciations of Stoicism go, seductive in its articulateness and energy, and therefore effective, however uninformed.