vendredi, 28 mars 2025

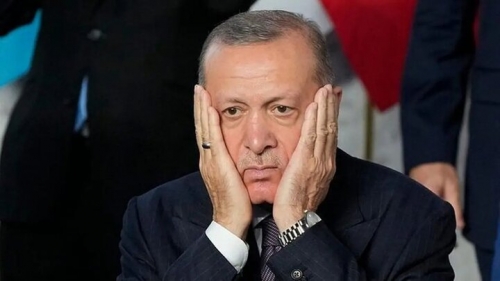

Erdoğan est désormais seul

Erdoğan est désormais seul

Alexander Douguine

Suite à l'arrestation du maire d'Istanbul, Ekrem İmamoğlu, de graves troubles ont éclaté et continuent de s'intensifier en Turquie. La crise s'aggrave. Mais pour analyser correctement la situation, plusieurs facteurs doivent être pris en compte.

Tout d'abord, le maire d'Istanbul, tout comme le maire d'Ankara, appartient à l'opposition libérale à Erdoğan. Il s'agit du Parti républicain du peuple (CHP), qui représente une alternative de gauche-libérale, laïque et généralement pro-européenne au parti d'Erdoğan, le Parti AK (Parti de la justice et du développement). Cette opposition est, en principe, orientée vers l'Occident et opposée à l'orientation islamique des politiques d'Erdoğan. En même temps, elle adopte une position assez hostile envers la Russie.

Deuxièmement, Erdoğan lui-même a récemment commis plusieurs erreurs politiques très graves. La plus significative d'entre elles est son soutien à la prise de pouvoir à Damas par les militants d'al-Jolani. C'est une erreur fatale parce qu'en agissant ainsi, Erdoğan a infligé un coup sérieux — peut-être irréparable — aux relations turco-russes et turco-iraniennes. Maintenant, ni la Russie ni l'Iran ne viendront en aide à Erdoğan. La situation s'est déjà retournée contre lui, et la crise pourrait s'intensifier davantage.

Je ne crois pas que l'Iran ou la Russie soient impliqués de quelque manière que ce soit dans les troubles en Turquie. Plus probablement, c'est l'Occident qui essaie de renverser Erdoğan. Néanmoins, son erreur syrienne est significative. Beaucoup en Turquie n'ont pas seulement échoué à la comprendre, mais ont également condamné cette politique d'Erdoğan qui, comme nous le voyons maintenant, a conduit au génocide des Alaouites et d'autres minorités ethno-religieuses, y compris les chrétiens. En effet, seul un politicien extrêmement myope pourrait remettre le pouvoir en Syrie à al-Qaïda. Et bien qu'Erdoğan ait généralement été considéré comme un homme d'État prévoyant, cette erreur, à mon avis, le hantera longtemps.

Un autre aspect est sa politique économique. La dévaluation de la lire, l'inflation galopante — tout cela sape une économie turque déjà fragile. Et bien sûr, ces échecs — tant en Syrie que dans l'économie — ainsi que le rapprochement d'Erdoğan avec l'Union européenne, avec les forces mondialistes, et son contact avec le chef du MI6, Richard Moore, poussent tous Erdoğan dans un piège. En conséquence, l'opposition libérale mais kemaliste (et donc nationaliste) en Turquie a saisi l'occasion de capitaliser sur ses échecs. Leur argument est : « Nous vous avions prévenus que ce qui s'était passé en Syrie serait une victoire pyrrhique, l'économie s'effondre, et nous avons une orientation plus forte vers l'Ouest qu'Erdoğan, sous lequel la Turquie ne sera jamais acceptée en Europe. »

Et puisque la Turquie a une démocratie fonctionnelle, Erdoğan n’a pas pu empêcher les populations d’Istanbul et d’Ankara de voter pour des leaders de l'opposition lors des élections municipales. En fin de compte, Erdoğan a décidé d'emprisonner le maire d'Istanbul. La question de savoir si c'était justifié ou non est presque sans importance — dans tout régime politique moderne, il est toujours possible de trouver des motifs pour emprisonner n'importe quel fonctionnaire (en politique moderne, il n'y a pas de personnes innocentes). La Turquie ne fait pas exception. Par conséquent, la question est uniquement celle de l'opportunité politique.

Erdoğan a décidé que les choses allaient mal pour lui et qu'il devait emprisonner son opposant le plus actif — Ekrem İmamoğlu. Pourtant, İmamoğlu est une figure affiliée à Soros, soutenue par des réseaux mondialistes, et Erdoğan n'aurait pu être soutenu dans cette démarche que s'il avait lui-même pris une position ferme contre cette faction liée à Soros. Cependant, comme l'avons déjà mentionné, Erdoğan avait précédemment poignardé dans le dos ses alliés — l'Iran et la Russie. Par conséquent, nous, Russes, ne pouvons pas le soutenir dans la situation actuelle. Et les Iraniens non plus.

C'est une situation très mauvaise pour Erdoğan. Tous ses opposants, profitant de ses erreurs accumulées au fil du temps, se sont soulevés en une même révolte — laquelle est une véritable révolution de couleur. Et ces kemalistes conservateurs, même alignés dans les forces armées, avec une orientation eurasienne — des militaires kémalistes qu'Erdoğan avait un jour accusés dans l'affaire toute fabriquée que fut "Ergenekon", et qui, en fait, l'avaient sauvé plus d'une fois (surtout lors de la tentative de coup d'État de 2016) — ne viendront plus à son secours.

En essence, Erdoğan se retrouve sans amis, ayant trahi tout le monde à plusieurs reprises. Je crois que sa situation est peu enviable. En même temps, nous devons garder une très grande prudence face aux manifestations en cours, car de la même manière que dans la plupart des révolutions de couleur, les mêmes organisateurs se tiennent derrière elles, y compris celle qui se déroule actuellement en Serbie. Au même temps, les mondialistes impliqués dans les manifestations sont une minorité — la majorité sont des gens ordinaires réellement mécontents de divers excès politiques au sein de la direction. Par conséquent, il y a aussi des raisons objectives à ce qui se passe — il semble qu'Erdoğan ait simplement épuisé sa marge d'erreur. Pourtant, il continue à faire des erreurs.

Il est difficile de dire ce qui pourrait rectifier la situation. Peut-être qu'une certaine forme de gouvernement d'unité nationale kemaliste impliquant des islamistes modérés (comme des membres du propre parti d'Erdoğan) pourrait émerger. Dans ce contexte, la question se pose : que se passe-t-il avec Devlet Bahçeli, le leader du Parti du mouvement nationaliste turc et le principal allié d'Erdoğan ? Il y a même des rumeurs selon lesquelles il serait mort, ce que les autorités auraient soi-disant dissimulé. Je pense que ce ne sont que des théories du complot — mais cette figure de la politique turque a vraiment vieilli et s'est affaiblie. Erdoğan ne peut plus compter sur lui ou sur ses "Loups gris", autrefois puissants, de redoutables nationalistes radicaux turcs.

Donc, encore une fois, je répète : l'avenir d'Erdoğan et de son régime semble sombre. Cependant, bien sûr, nous préférerions avoir une Turquie souveraine avec une politique étrangère indépendante comme voisine — de préférence amicale, bien que nous soyons préparés même si elle nous devient hostile. La Russie est prête à toute éventualité.

15:24 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, erdogan, ekram imamoglu, turquie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 26 mars 2025

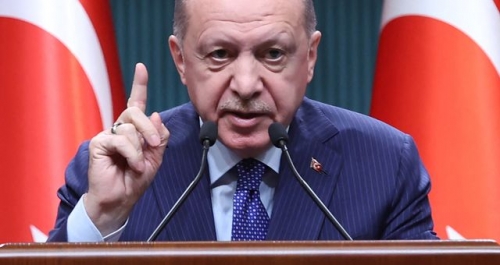

Georgescu non et Imamoglu oui ? Erdogan se fiche des subtilités électorales et ne pense qu'à la Grande Turquie

Georgescu non et Imamoglu oui ? Erdogan se fiche des subtilités électorales et ne pense qu'à la Grande Turquie

Enrico Toselli

Source: https://electomagazine.it/georgescu-no-e-imamoglu-si-erdo...

Un gouvernement inéluctablement démocratique fait arrêter le candidat de l’opposition ayant le plus de chances de gagner les élections. Et l’empêche de se porter candidat. Pendant ce temps, il bloque aussi le parti qui soutient le candidat. Et que font les eurodingues de Bruxelles ? Cela dépend. Dans un cas, celui de Georgescu en Roumanie, ils soutiennent l’arrestation et l’annulation de la candidature, au nom de la démocratie, ça va sans dire. Dans l’autre cas, celui d’Imamoglu en Turquie, on s’indigne du comportement antidémocratique d’Erdogan.

Et les médias suivent les directives des eurodingues. On minimise les manifestations de protestation en Roumanie et on met bien en exergue celles qui se déroulent en Turquie. Où, évidemment, Erdogan s’en fiche, malgré les répercussions sur la bourse et le change, pour bien clarifier que les spéculateurs internationaux sont toujours prêts à faire comprendre de quel côté ils se trouvent.

Imamoglu, maire d'Istanbul, avait sans aucun doute de bonnes chances de s'imposer aux élections prévues en 2028, même si, dans trois ans, il peut se passer n'importe quoi. Mais Erdogan a une vision du monde, et de la Turquie, qui ne dépend pas de la conjoncture électorale. Il veut reconstituer l'empire ottoman et ne peut pas se contenter de méditer les subtilités des règles électorales.

Il est d’ailleurs en bonne compagnie. Peu d'États de l'Union européenne ont reçu un mandat des électeurs pour faire la guerre contre la Russie et pour voler les économies des familles européennes. Mais à Bruxelles, ils se fichent des électeurs et agissent uniquement pour rendre heureux les marchands de mort.

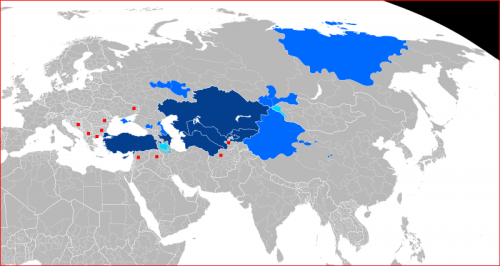

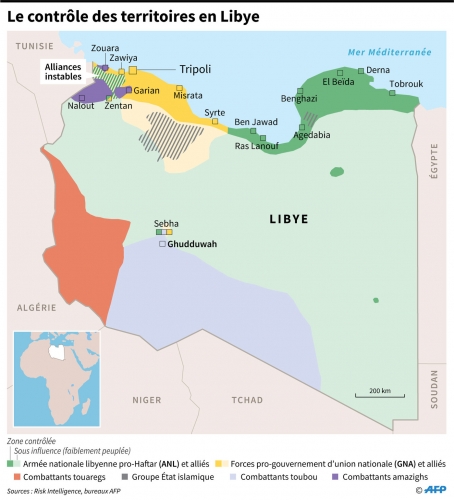

Erdogan, pour sa part, s'engage à renforcer le rôle de la Turquie. Et il réussit. Parfois en utilisant l'Azerbaïdjan comme bras armé ou comme instrument pour des accords économiques – des confrontations avec l'Arménie aux accords avec l'Europe pour le gaz – parfois en utilisant les jihadistes comme en Syrie, parfois en intervenant directement comme en Libye.

Une politique à large spectre, qui implique les pays turcophones d’Asie centrale et qui prévoit la plus totale ambiguïté dans les relations avec Moscou et Pékin, et même avec Tel Aviv : de grandes menaces publiques contre le boucher israélien, puis des accords économiques en sous-main.

Tout est bon pour rendre à nouveau grande la Turquie. Un slogan déjà utilisé? Oui, mais peu importe à Erdogan. Qui veut être le maître de la Méditerranée. D’ailleurs, si ses adversaires sont Tajani et Ursula von der Leyen, le match se gagne facilement.

15:28 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, turquie, erdogan, ekram imamoglu, politique internationale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Protestations en Turquie: Erdogan sous pression

Protestations en Turquie: Erdogan sous pression

Source: https://report24.news/proteste-in-der-tuerkei-erdogan-unt...

Le président Recep Tayyip Erdogan a fait arrêter son plus grand rival politique, le maire d'Istanbul, Ekrem Imamoglu. Cela a entraîné des manifestations dans plusieurs villes. Des centaines de manifestants ont été arrêtés. La Turquie est confrontée à des troubles de masse contre le "sultan du Bosphore", dont la position s'affaiblit lentement.

La situation en Turquie est tendue. L'arrestation du maire d'Istanbul Ekrem Imamoglu (photo) a déclenché des manifestations à l'échelle nationale, rappelant les grandes manifestations de 2013, lorsque les citoyens s'étaient soulevés contre la destruction du parc Gezi. Dans la nuit de samedi, le ministère de l'Intérieur a signalé que 343 personnes avaient été arrêtées dans plusieurs villes, dont Istanbul et Ankara. Ces mesures ont été justifiées par l'argument de la nécessité de maintenir l'ordre public. Cependant, la réalité est beaucoup plus complexe et soulève des questions sur les droits démocratiques en Turquie.

Les manifestations, qui ont commencé le 19 mars, ne sont pas seulement une réaction à l'arrestation d'Imamoglu, mais reflètent un mécontentement plus profond face à la situation politique et économique du pays. Le maire a été arrêté chez lui sous des accusations de terrorisme et de corruption, ce que beaucoup considèrent comme une action politiquement motivée. "Il y a une grande colère. Les gens sortent spontanément dans la rue. Certains jeunes sont politisés pour la première fois", a déclaré Yuksel Taskin, député du Parti républicain du peuple (CHP), considéré comme social-démocrate, à propos des développements actuels.

Imamoglu, considéré comme un rival sérieux du président Recep Tayyip Erdogan, était prévu comme candidat de son parti, le CHP, pour les prochaines élections présidentielles de 2028, qui se tiendront le 23 mars. Son arrestation pourrait être interprétée comme une tentative de réduire l'opposition politique et de renforcer le contrôle sur l'opinion publique. "Je constate aujourd'hui lors de mon interrogatoire que mes collègues et moi sommes confrontés à des accusations et à des diffamations inimaginables", a déclaré Imamoglu lors de son interrogatoire par la police.

Les accusations portées contre lui sont graves : diriger une organisation criminelle, corruption et soutien au Parti des travailleurs du Kurdistan (PKK), lequel est interdit. Ces accusations sont non seulement juridiquement mais aussi politiquement explosives. Elles visent à discréditer Imamoglu et ses partisans et à manipuler la perception publique. Le fait que l'Université d'Istanbul ait déclaré un jour avant son arrestation que son diplôme était invalide renforce l'impression qu'il s'agit bien d'une manœuvre politique. En Turquie, seuls les titulaires d'un diplôme universitaire peuvent se porter candidat à des fonctions politiques.

La réaction du gouvernement aux manifestations est tout aussi préoccupante. Le ministre de l'Intérieur, Ali Yerlikaya, a annoncé que des centaines de comptes sur les réseaux sociaux avaient été identifiés et que 37 utilisateurs avaient été arrêtés pour "publications provocatrices incitant à des crimes et à la haine". Cela montre que le gouvernement s'attaque non seulement aux manifestants, mais aussi à la libre expression par voie numérique. Les restrictions sur les plateformes sociales sont un autre signe de la répression croissante en Turquie.

Les manifestations ne sont pas seulement un signe de mécontentement face à l'arrestation d'Imamoglu, mais aussi un signe de la frustration généralisée face à la situation économique et sociale du pays. "Le sentiment d'être piégé dans tous les domaines – économique, social, politique et même culturel – est déjà largement répandu", a déclaré le journaliste et auteur Kemal Can. Ces sentiments sont profondément enracinés dans la population et pourraient conduire à un tournant dans le paysage politique de la Turquie.

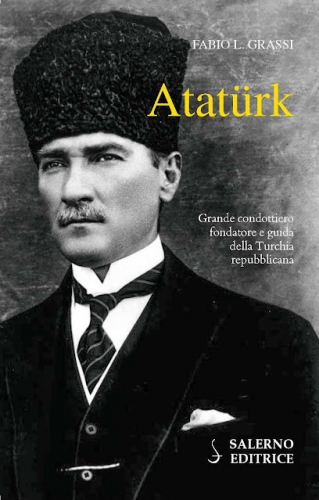

Le CHP, qui se situe dans la tradition laïque et kémaliste du fondateur de l'État Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, a appelé ses partisans à manifester pacifiquement et a souligné que les arrestations sont politiquement motivées. Le parti se considère comme responsable de représenter la voix des citoyens et de lutter contre les mesures répressives du gouvernement. Les événements actuels pourraient servir de coup de fouet pour de nombreux citoyens qui se sont jusqu'à présent tenus à l'écart de la politique.

La question qui se pose désormais est de savoir si ces manifestations peuvent conduire à un mouvement plus large qui transformerait fondamentalement les relations politiques en Turquie. Le gouvernement d'Erdogan, orienté vers le grand empire ottoman, composé de l'islamiste AKP et de l'islamo-nationaliste MHP, a déjà montré qu'il était prêt à réprimer toute forme d'opposition d'une main de fer. Cependant, la colère des citoyens pourrait être un facteur imprévisible qui déréglerait les calculs politiques du gouvernement.

D'un autre côté, il convient de considérer qu'Erdogan ne s'est pas fait beaucoup d'amis en Occident (notamment au sein de l'OTAN, des États-Unis et de l'UE) avec sa politique grande-ottomane et ambivalente. Un changement vers un président pro-occidental "plus fiable" comme Imamoglu pourrait jouer en faveur de l'alliance militaire transatlantique. Dans ce cas, la Turquie pourrait assumer des rôles au Moyen-Orient et dans le Caucase pour le compte des États-Unis, qui souhaitent également se concentrer davantage sur l'Asie de l'Est – la Chine et la Corée du Nord.

12:40 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, politique internationale, turquie, ekram imamoglu, erdogan |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 12 février 2025

Erdogan part à la conquête de la Circassie russe

Erdogan part à la conquête de la Circassie russe

Enrico Toselli

Source: https://electomagazine.it/erdogan-parte-alla-conquista-de...

Il a dévoré la Syrie sans coup férir, abandonnant une partie du territoire à Israël. Mais à Tel-Aviv, il ne faudrait pas être trop tranquille pour l’avenir. Désormais, Erdogan tourne son regard vers l’Abkhazie sous contrôle russe, première étape dans la construction d’une Circassie indépendante de Moscou mais dépendante d’Ankara. Évidemment, les dirigeants de l’Union européenne – tous absents lorsque a eu lieu la distribution d’intelligence – célèbrent l’événement. Porter un coup à Poutine mérite d’être fêté avec champagne et caviar, aux frais des sujets européens.

Prendre l’Abkhazie aux Russes signifie aussi se rapprocher de la Géorgie, en poussant Tbilissi à abandonner ses relations avec Moscou pour se tourner vers Bruxelles. Naturellement, les grands politiciens européens ne se rendent pas compte que le passage de l’Abkhazie sous l’hégémonie turque précéderait celui de toute la Géorgie. Et ensuite, pas à pas, viendrait le tour des autres pays du Caucase.

Ursula sera surprise, tout comme toute sa clique, mais Erdogan agit dans l’intérêt de la Turquie, pas dans celui de Bruxelles. On peut même comprendre Zelensky, qui rêve d’affaiblir Poutine grâce à Erdogan, car le bandit de Kiev n’a absolument rien à faire de l’Europe. Mais l’enthousiasme de l’UE, occupée à attiser des troubles à Tbilissi, est totalement déplacé.

Quant à la Russie, une fois de plus, elle paie son incapacité totale à agir sur le front du soft power. Ce n’est qu’à l’approche du scrutin en Abkhazie que Moscou a pris conscience du problème et de l’efficace campagne électorale turque. Ankara a avancé sur le terrain culturel et des revendications ethniques. Moscou, avec un énorme retard, a simplement envoyé un peu d’argent. Cette affaire est assez pathétique et se révèle totalement inefficace. D’ailleurs, les Russes ont commis les mêmes erreurs en Europe occidentale, persuadés que les missiles et les drones suffisent à faire basculer les équilibres.

Staline, sur ce point, était bien plus malin.

19:55 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (2) | Tags : erdogan, turquie, circassie, abkhazie, caucase, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 06 avril 2024

Questions... turques

Questions... turques

Andrea Marcigliano

Source: https://electomagazine.it/robe-turche/

Erdogan a perdu. Célébrations dans les rues des métropoles turques: Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir...

Célébrations aussi dans les médias italiens. Ils soulignent la raclée prise par le sultan, qui a toujours été présenté à notre opinion publique comme un méchant despote.

Mais.

Mais il s'agissait d'élections locales. Où l'AKP, le parti d'Erdogan, visait à reconquérir Ankara et Istanbul, déjà gouvernées par l'opposition du CHP. En Italie, ce dernier s'est présenté comme un parti social-démocrate, ou plus simplement socialiste.

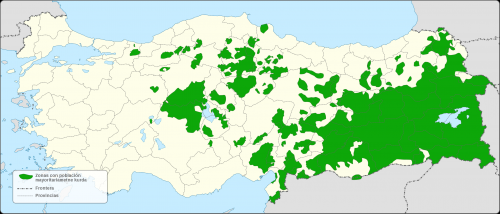

En réalité, c'est le parti qui revendique l'héritage d'Atatürk. Laïque et nationaliste. Et les foules qui fêtaient dans les rues des deux métropoles, sans surprise, scandaient: Kemal ! Kemal !

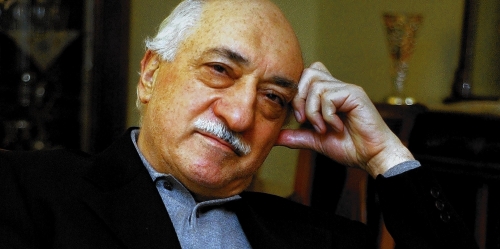

Comme l'a souligné Carlo Marsili (photo), longtemps ambassadeur à Ankara et aujourd'hui plus grand spécialiste italien de la politique turque, ce résultat prouve de manière irréfutable que la Turquie est une démocratie. J'ajouterai qu'il en va de même pour toutes les absurdités qui sont dites et écrites en Italie à propos du despotisme d'Erdogan.

Il s'agissait d'élections locales. Le choix des maires. Et pourtant, elles étaient chargées d'un poids politique très fort. Le défi entre l'AKP, ou plutôt Erdogan, qui y avait mis tout son poids et sa tête, et l'opposition. Ou plutôt le CHP, dirigé par le maire d'Istanbul Ekrem Imamoglu (photo). Lequel a d'ailleurs saigné à blanc tous les autres partis d'opposition. Sauf dans les provinces kurdes, où le succès prévisible et modéré du parti minoritaire de référence a été enregistré.

Le fait le plus important, cependant, est que le CHP semble avoir dépassé le parti d'Erdogan dans les pourcentages nationaux. Ce qui, automatiquement, désigne Imamoglu pour les prochaines élections présidentielles en tant que successeur du sultan.

Erdogan paie principalement une crise économique interne et l'échec de nombre de ses politiques sociales. Il s'est ainsi aliéné le soutien de la classe moyenne urbaine, qui soutenait l'AKP à l'époque.

Toutefois, il s'agit là de problèmes internes à la République turque. Des problèmes turcs, pour l'analyse desquels je me réfère à ce que des experts authentiques tels que Carlo Marsili et le professeur Fabio L. Grassi (photo) de l'université Sapienza écrivent et disent ces jours-ci. Tous deux font d'ailleurs partie du comité scientifique de la Fondation Nodo di Gordio.

Il est toutefois intéressant de noter comment un tel résultat pourrait affecter la politique étrangère d'Ankara. Notamment parce que le CHP est ouvertement atlantiste. Et Imamoglu semble avoir bénéficié de tout le soutien possible, et pas seulement moral, de Washington.

La position internationale de la Turquie est en effet... ambiguë. Erdogan, suivant les lignes de fond stratégiques turques liées à la tradition ottomane, a conduit le grand pays anatolien à jouer sur plusieurs tableaux. Dans l'OTAN et, en même temps, dans le dialogue avec Moscou. Un jeu complet qui a fait d'Ankara un acteur géopolitique présent et influent non seulement dans les Balkans et au Moyen-Orient, mais aussi dans tout le Maghreb et la Corne de l'Afrique.

Une stratégie tous azimuts qui a éveillé les soupçons (et c'est un euphémisme) de Washington. Lequel ne peut renoncer à son alliance stratégique avec la Turquie, mais ne pardonne pas à Erdogan le "dialogue" avec Moscou et Téhéran. D'où le soupçon (sic !) qu'une longa manus "amie"... était derrière le coup d'État manqué de 2016.

Erdogan a maintenant près de quatre ans pour retrouver le consensus et corriger ses erreurs de politique intérieure. Et rien n'est encore joué quant à l'avenir d'Ankara. Toutefois, il faudra voir comment le sultan se comportera sur la scène internationale pendant cette période. Compte tenu de son caractère, je doute qu'il accepte de rentrer dans le rang comme un canard boiteux. Et, peut-être, faudra-t-il s'attendre à d'autres... surprises.

19:23 Publié dans Actualité, Politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, politique internationale, politique, turquie, erdogan, asie mineure |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 16 décembre 2023

Et maintenant, Biden sanctionne Erdogan et les Émirats. Biden cherche des ennemis passionnément

Et maintenant, Biden sanctionne Erdogan et les Émirats. Biden cherche des ennemis passionnément

Ala de Granha

Source: https://electomagazine.it/ed-ora-biden-sanziona-erdogan-e-gli-emirati-cercasi-nemici-appassionatamente/

Les États-Unis sanctionnent des entreprises turques et émiraties, ainsi que chinoises, pour avoir vendu à la Russie des produits que Washington considère comme dangereux pour le pauvre Zelensky. Et, ayant une mentalité de jardin d'enfants, les Etats-Unis ne font aucune distinction entre alliés, semi-alliés et adversaires. Tout comme ils ignorent le respect des engagements et de la légalité internationale. "Je suis moi et vous n'êtes pas un c....". La seule chose qu'ils ont apprise de la vieille Europe, c'est la logique du Marquis Del Grillo.

Parce qu'eux, les maîtres américains, peuvent fabriquer et vendre à Israël les bombes au phosphore interdites. Et le "boucher de Tel-Aviv" peut les utiliser contre les enfants de Gaza. Personne n'intervient pour punir Netanyahou et ceux qui lui fournissent des armes. Pas de sanctions contre les criminels, s'ils sont sur la "bonne" liste.

Mais Erdogan s'est retrouvé sur la liste des "vilains" alors que la Turquie est membre de l'OTAN. Oui, mais il a osé critiquer les "bouchers israéliens", à qui il continue pourtant de vendre de l'énergie. Et puis il ne ratifie pas l'adhésion de la Suède à l'OTAN : un méchant ! Peu importe, à Washington, qu'Erdogan tergiverse parce que les Américains eux-mêmes ne veulent pas lui vendre des avions pourtant promis à la Turquie. La politique du deux poids deux mesures se retrouve dans toutes les décisions des Yankees. Ils peuvent décider de respecter ou non leurs engagements, les autres ne le peuvent pas.

Ainsi, la politique commerciale d'Ankara, comme celle des Émirats et de la Chine, doit être décidée à Washington. Mais la Chine ne peut pas se permettre de réagir en bloquant les livraisons de ce dont les États-Unis ont besoin. Sinon, les journalistes italiens pleureront sur le comportement incompréhensible et intolérable de Pékin. Il faut accepter les sanctions sans réagir. Parce qu'elles sont établies par les bons. Et les journalistes italiens sont toujours du côté des bons. Le pluralisme de l'information devrait être autre chose, mais l'éthique professionnelle veut que ce qui est établi par les Américains soit la loi absolue.

16:22 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : états-unis, joe biden, erdogan, turquie, émirats, chine, politique commerciale, sanctions, politique internationale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 04 décembre 2023

Erdogan tonne contre Israël mais vend de l'énergie à Tel Aviv. Et seuls les journalistes américains ont peur

Erdogan tonne contre Israël mais vend de l'énergie à Tel Aviv. Et seuls les journalistes américains ont peur

Enrico Toselli

Source: https://electomagazine.it/erdogan-tuona-contro-israele-ma-vende-energia-a-tel-aviv-e-si-spaventano-solo-i-giornalisti-usa/#google_vignette

Le "boucher de Tel-Aviv", comme Erdogan a appelé Netanyahou, a recommencé à massacrer des civils à Gaza, tandis que ses tireurs d'élite ont assassiné deux enfants de 9 ans en Cisjordanie. Et le dirigeant turc hausse encore le ton. Il fulmine. Il demande que les Israéliens soient jugés pour crimes de guerre. Mais, dans les faits, il ne fait absolument rien. À tel point que les Iraniens, furieux, ont fait capoter une réunion au sommet. Téhéran voudrait qu'Ankara ferme les robinets de l'énergie vendue à Israël, mais Erdogan regarde les comptes et, tout en vociférant, continue d'encaisser.

Parce que les Palestiniens sont des amis, mais que les Israéliens ont l'argent. Logique levantine, trop compliquée pour les jeunes esprits des médias américains qui ne peuvent comprendre le triple, quadruple jeu des Turcs sur la scène internationale. Pour eux, les cow-boys de l'information, vous êtes soit avec eux, soit contre eux. Si vous obéissez à RimbanBiden, si vous défendez les intérêts américains, vous faites partie des gentils. Comme Meloni, comme Scholz. Si vous êtes contre eux, vous êtes un méchant à la tête d'un État voyou. Cela vaut pour la Russie, pour l'Iran, pour la Chine (bien qu'il faille le dire à voix basse).

Mais il y a eu ensuite le comportement ambigu de ceux qui faisaient partie des gentils. La Turquie, surtout. Celle que les esprits simples des journalistes yankees appelaient "la malade de l'Otan". Car Erdogan n'a pas encore donné son feu vert à l'adhésion de la Suède. Il augmente le prix pour l'accorder. Il veut des avions que les États-Unis ne veulent pas lui donner. Et pendant ce temps, il flirte avec Poutine et fait du commerce avec Zelensky. Il s'étend en Afrique et trouve des intérêts communs avec l'Iran. Il ignore les Ouïghours, son peuple frère, en Chine pour avoir les coudées franches dans les négociations avec Pékin. Il fait la nique à l'Union européenne dont, après tout, il peut aussi se passer. Il dit oui à tout le monde et fait ce qu'il pense être bon pour la Turquie.

Dans la pratique, il se contente de faire de la politique étrangère. De manière cynique, parfois exaspérante. Mais en gardant à l'esprit, contrairement à d'autres, qu'il est là pour protéger les intérêts turcs. Pas ceux des États-Unis, de la Russie ou de la Chine. Conscient qu'il est un non-arabe avec de nombreux voisins arabes. Et d'être placé dans un carrefour extrêmement complexe et difficile.

Il est sans doute plus facile de rester dans la niche à attendre les ordres de Washington. Avec la seule pensée de devoir faire des déclarations absurdes pour justifier l'injustifiable. En faisant semblant de ne pas voir que les voisins deviennent eux aussi nerveux. Mais il suffit d'un voyage dans les châteaux pour que la politique étrangère soit oubliée.

19:54 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : erdogan, turquie, politique internationale, israël, palestine, levant, proche-orient |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 29 mai 2023

Erdogan gagne, les néoconservateurs perdent

Erdogan gagne, les néoconservateurs perdent

Source: https://www.piccolenote.it/mondo/vince-erdogan-perdono-i-neocon

C'est un Erdogan rajeuni qui a célébré sa réélection devant une foule immense. L'Occident avait parié contre lui et a "perdu", comme il l'a dit dans son premier discours. Et, en effet, les milieux hyper-atlantistes avaient fait des pieds et des mains pour soutenir son adversaire Kemal Kilicdaroglu, qui avait promis de ramener la Turquie à l'obéissance silencieuse aux diktats de l'OTAN et d'engager Ankara dans l'acharnement anti-russe (Responsible Statecraft).

Même si les intentions de Kilicdaroglu étaient quelque peu illusoires, puisque toutes les forces qui le soutenaient n'avaient pas le même penchant atlantiste, cela aurait certainement affaibli l'axe existant avec la Russie.

Cela n'a pas été le cas, et maintenant Erdogan, qui pour gagner s'est éloigné encore plus de l'Occident, se sentira encore plus ferme pour persévérer dans la ligne suivie jusqu'à présent, qui lui a attiré le consensus dans son pays.

Une ligne qui ne renie pas les relations établies par Kemal Ataturk avec l'Occident, mais qui, en même temps, ne se sent pas liée par elles, conduisant son pays à rétablir avec l'Orient des relations qui avaient été rompues au nom des diktats atlantistes.

Il est intéressant de noter que la victoire électorale n'a pas suscité de protestations, bien que certains médias aient fait état d'une prétendue fraude électorale de la part de l'autorité centrale.

En d'autres temps (en Ukraine - en 2014 - ou au Venezuela - en 2019 - pour ne citer que deux cas frappants), de telles allégations avaient servi de base au déclenchement de manifestations de rue contre la victoire volée, manifestations que l'Occident avait utilisées comme levier pour tenter de renverser le gouvernement élu.

Le fait qu'Erdogan a également été capable de gérer la période post-électorale est une autre indication de la force du sultan.

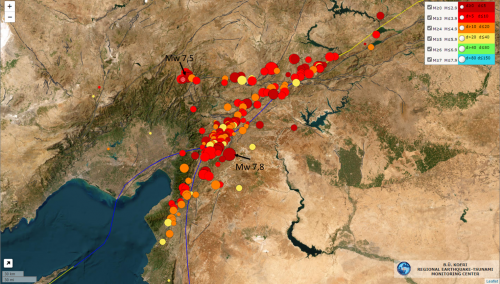

Il reste les nombreux problèmes de la Turquie, auxquels Erdogan est appelé à s'attaquer, notamment la reconstruction des zones touchées par le récent tremblement de terre. Et le caractère autoritaire de son gouvernement, un peu dénoncé par tous les médias occidentaux. Une propension qui n'est pourtant pas une marque de fabrique du sultan, la Turquie n'ayant connu que des pouvoirs forts depuis l'époque d'Atatürk.

Une dernière remarque concerne la guerre d'Ukraine, à propos de laquelle Erdogan a joué le rôle de médiateur, parvenant même à accueillir plusieurs réunions entre les parties en conflit et à faciliter le seul accord conclu entre elles, celui concernant le transit des céréales ukrainiennes.

Un travail qu'il a dû abandonner ces derniers mois en raison de l'engagement électoral qui l'a complètement absorbé. Maintenant qu'il est plus fort, il peut reprendre ce rôle, augmentant ainsi les chances de ceux qui tentent de rétablir la paix dans ce pays européen ravagé.

19:58 Publié dans Actualité, Politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, politique internationale, turquie, erdogan, asie mineure, politique, élections turques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

La Turquie maintient le cap : Erdogan clairement réélu au second tour

La Turquie maintient le cap: Erdogan clairement réélu au second tour

Source: https://zuerst.de/2023/05/29/die-tuerkei-bleibt-auf-kurs-erdogan-im-zweiten-wahlgang-klar-bestaetigt/

Ankara. La Turquie a voté - et elle a finalement choisi assez clairement Erdogan lors du second tour de l'élection présidentielle du 28 mai qui opposait le chef du gouvernement de longue date, Erdogan, à son challenger Kemal Kilicdaroglu. Erdogan a obtenu 52,16% des voix dimanche soir après le dépouillement de tous les votes, contre 47,84% pour Kilicdaroglu. Le troisième candidat, Sinan Ogan, de la coalition de droite Ata Ittifaki, avait également voté pour Erdogan au premier tour, il y a deux semaines, et a appelé ses partisans à voter pour lui au second tour.

Le résultat du scrutin est avant tout une déception pour les élites libérales de gauche occidentales, qui avaient clairement favorisé Kilicdaroglu. Ce dernier s'était engagé à renforcer les liens entre la Turquie et l'Occident et, surtout, à promouvoir les "valeurs européennes" telles que le culte LGBTiste. Pourtant, il n'y a pas si longtemps, son propre parti, le CHP (Parti républicain du peuple), était considéré par les observateurs occidentaux comme "élitiste" et "nationaliste". L'alliance électorale de Kilicdaroglu avait même envisagé un "changement de régime" en cas d'arrivée au pouvoir, afin de mettre la Turquie sur la voie de l'Occident.

Malgré les difficultés économiques considérables de la Turquie, l'inflation galopante et, plus récemment, les manquements du gouvernement après le tremblement de terre de début février, la majorité des électeurs turcs n'ont pas voulu de changement et ont manifesté leur confiance dans le président sortant Erdogan, qui dirige le pays depuis maintenant 20 ans.

Le Premier ministre hongrois Orbán a été l'un des premiers à le féliciter dimanche. Sur Twitter, il a écrit qu'il s'agissait d'une "victoire sans équivoque". Le chef du Kremlin, M. Poutine, a également adressé ses félicitations dimanche soir, avant même le dépouillement de tous les votes. Au grand dam de l'Occident, Erdogan a renforcé ses relations avec la Russie au cours des dernières années et ne supporte pas les sanctions occidentales.

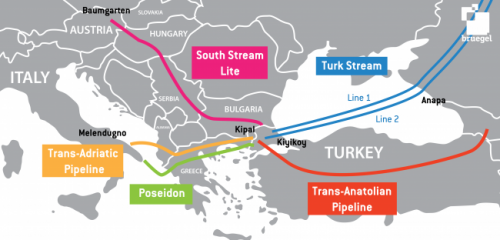

Au contraire, Ankara peut se réjouir du rôle privilégié d'intermédiaire énergétique russe - en contrepartie des voies de transport de gaz et de pétrole d'Europe de l'Est, de plus en plus incertaines ces dernières années, le gaz russe s'écoule depuis 2020 directement de la Russie vers la Turquie via le gazoduc Turk Stream.

Le challenger malheureux Kilicdaroglu a entre-temps reconnu le résultat des élections et a déclaré qu'il n'avait pas l'intention de les contester (mü).

Demandez ici un exemplaire gratuit du magazine d'information allemand ZUERST ! ou abonnez-vous dès aujourd'hui à la voix des intérêts allemands !

Suivez également ZUERST ! sur Telegram : https://t.me/s/deutschesnachrichtenmagazin

19:47 Publié dans Actualité, Politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, turquie, asie mineure, politique, élections turques, erdogan |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 28 mai 2023

Fractures turques

Fractures turques

par Georges FELTIN-TRACOL

Sinan Oğan est la grande surprise du premier tour de la présidentielle turque. Certes, il ne se qualifie pas pour le second tour, mais ses 5,17 % pèsent déjà sur le duel entre le président sortant Recep Tayyip Erdoğan qui frôle la réélection avec 49,52 % et son rival républicain du peuple Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu (44,88 %). Quant au quatrième candidat issu du Parti de la mère-patrie d’orientation libérale-conservatrice, Muharrem İnce se retire dans les derniers jours de la campagne, d’où son 0,43 %.

Quelques esprits forts pointent aussitôt l’activisme débordant de l’AKP (Parti de la Justice et du Développement) auprès des classes les plus populaires, activisme qualifié de « clientélisme ». Dommage qu’ils ne mentionnent jamais le clientélisme gigantesque du Parti démocrate de Joe Biden dans certains États, comtés et municipalités des États-Unis.

On peut croire que les électeurs de Sinan Oğan se reporteront sur le président Erdoğan au second tour. La vie politique turque est en réalité plus subtile. Âgé de 55 ans et d’origine azerbaïdjanaise, Sinan Oğan a étudié à Moscou au début du XXIe siècle. Il milite de 2010 à 2015 au sein du mouvement pantouranien MHP (Parti d’action nationaliste) de Devlet Bahçeli dont il devient l’un des députés. En 2015, le MHP l’exclut, car il refuse le rapprochement entamé avec l’AKP.

À l’occasion de cette campagne présidentielle, Sinan Oğan se présente au nom de l’Alliance ancestrale, une coalition électorale récente des pantouraniens radicaux du Parti de la Victoire, des conservateurs libéraux du Parti de la Justice, des kémalistes sociaux du Parti « Mon Pays » et des progressistes du Parti de l’Alliance turque. Le candidat de cette entente veut d’une part interdire l’ensemble des formations politiques kurdes, séparatistes et loyalistes. Il dénonce d’autre part avec une rare insistance les 4,5 millions d’étrangers dont 3,5 millions de réfugiés syriens. Il ne souhaite pas assister au début d’un grand remplacement des Turcs. Il se montre enfin fort méfiant envers les islamistes.

C’est un point d’accord avec Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu dont les aïeux kurdes et alévis seraient originaires de la région arabophone iranienne du Khouzistan. Les observateurs le peignent régulièrement en pantin atlantiste, ce qui est exagéré. Le candidat kémaliste entretient volontiers de bonnes relations avec l’Irak, l’Iran et la Syrie. S’il était élu, sa présidence provoquerait tôt ou tard de profondes divergences au sein de l’Alliance de la nation entre les pro-occidentaux et les tenants du non-alignement.

La bipolarisation exprimée au moment de la présidentielle masque un foisonnement politique considérable avec des unions circonstancielles et hétéroclites dues au mode de scrutin. Un multipartisme vivace s’épanouit sous un apparent dualisme pour le plus grand plaisir des électeurs. L’abstention est autour de 14 % et les votes blancs et nuls ne dépassent pas les 2 %.

L’Alliance de la nation regroupe les kémalistes historiques du CHP (Parti républicain du peuple), les conservateurs musulmans du Parti démocrate, les islamistes traditionalistes du Parti de la Félicité, le Parti de la Démocratie et du Progrès, le Parti pour le changement de la Turquie, le Parti du Futur de l’ancien Premier ministre AKP Ahmet Davutoğlu, et les nationalistes du Bon Parti. Fondé et dirigé par Meral Akşener qu’on dit proche des milieux atlantistes, le Bon Parti soutient une ligne nationale-laïque intransigeante. Ministresse de l’Intérieur entre 1996 et 1997, elle a fortement réprimé l’opposition kurde, d’où des tiraillements répétés avec ses partenaires de la « Table des Six ». L’hétérogénéité de la coalition explique-t-elle son échec aux élections législatives ?

En effet, le 14 mai dernier, les électeurs turcs participent à la fois aux élections présidentielles et législatives. Depuis la révision constitutionnelle de 2017 qui établit un régime présidentialiste, les mandats du président et des députés sont concomitants. Si le président démissionne ou s’il dissout le parlement, chef d’État et députés retourneront en même temps aux urnes. Cette articulation originale a été proposée dans la décennie 1990 en France par Jean-Pierre Chevènement qui reprenait une idée du club Jean-Moulin, un cénacle de la gauche technocratique des années 1960.

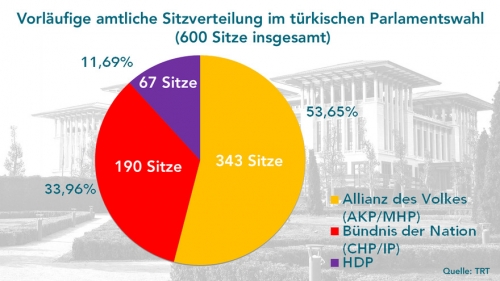

La Grande Assemblée nationale compte 600 membres élus pour cinq ans au scrutin proportionnel de liste bloquée à un seul tour dans 87 circonscriptions, en général des provinces mais pas toujours, au prorata du nombre d’habitants. Le seuil d’élection de 10 % a été abaissé à 7 %.

L’Alliance de la nation réalise 35,02 %, gagne 24 sièges, soit 212 élus (169 pour le CHP et 43 pour le Bon Parti). Elle subit la concurrence inévitable de l’Alliance du travail et de la liberté qui rassemble les Kurdes du HDP (Parti démocratique des peuples), le Parti des travailleurs de Turquie et le Parti de la Gauche verte éco-socialiste libertaire. Ce regroupement de gauche sociétale fait 10,54 %, compte 65 députés et perd deux sièges.

Le grand vainqueur des législatives est donc le camp présidentiel avec 49,40 %. Malgré une perte de 26 sièges et un recul de près de sept points par rapport à 2018, l’Alliance du peuple remporte 323 élus : 268 pour l’AKP, 50 pour le MHP qui augmente d’un siège et 5 pour les islamistes du Nouveau parti de la Prospérité de Fatih Erbakan, fils du mentor d’Erdoğan. Il faut inclure dans cette alliance présidentielle les nationaux-islamistes panturcs du Parti de la Grande Unité qui perdent leur unique siège, les sociaux-démocrates du Parti de la Gauche démocratique et les Kurdes islamistes traditionalistes anti-séparatistes du Parti de la Cause libre qui s’inspirent de la Garde de Fer roumaine. Pour l’anecdote, le parti La Patrie de l’eurasiste de gauche radicale Doğu Perinçek ne recueille pour sa part que 54.789 voix (0,10 % et perd 0,13 point…).

Si Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu accède à la présidence de la République, il devra cohabiter avec un parlement hostile bien que la nouvelle constitution limite strictement ses prérogatives. On comprend mieux pourquoi Sinan Oğan se pose en faiseur de roi. Il a dès à présent interpellé les deux finalistes au sujet de l’immigration massive qui bouleverse la donne démographique turque.

La Turquie s’intègre de plus en plus dans les méandres de la « société liquide » ultra-libérale 3.0. Le surgissement de Sinan Oğan sur la scène politique signale la radicalisation nationale et identitaire d’une opinion publique très fracturée. Peu importe le président élu, le Bloc occidental atlantiste devra prendre en compte une nation turque fière et sûre d’elle-même. L’échéance électorale du 28 mai prochain se révèle ainsi décisif non seulement pour l’avenir de la Sublime Porte, mais aussi pour l’Europe, le Proche-Orient, le Caucase, l’espace pontique, l’Asie Centrale et même le continent africain.

GF-T

- « Vigie d’un monde en ébullition », n° 75, mise en ligne le 23 mai 2023 sur Radio Méridien Zéro.

11:47 Publié dans Actualité, Politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : turquie, erdogan, sinanogan, politique, politique internationale, asie mineure |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 12 mai 2023

La Turquie à la veille d'élections cruciales

La Turquie à la veille d'élections cruciales

Source: https://katehon.com/ru/article/turciya-nakanune-reshayush...

La Turquie organise des élections présidentielles et législatives le 14 mai prochain. La situation politique interne du pays est très tendue. De facto, l'avenir du pays se jouera ce jour-là.

Principaux rivaux

L'événement principal des prochains jours en Turquie est l'élection présidentielle. Les deux principaux candidats sont le président sortant Recep Tayyip Erdogan et Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, chef du Parti républicain du peuple (CHP). Les sondages d'opinion - selon les sympathisants des sondeurs, ils donnent un avantage de 1 % à l'un ou l'autre candidat. Mais un second tour est également tout à fait possible, car outre Kılıçdaroğlu et Erdoğan, plusieurs autres candidats se présentent et il est possible qu'aucun des principaux prétendants n'obtienne plus de 50 % des voix le 14 mai. Un second tour devrait alors être organisé dans une quinzaine de jours.

L'opinion publique est divisée en deux. Il s'agit en grande partie d'un vote pour ou contre Erdogan. Ainsi, Kılıçdaroğlu est soutenu par une coalition hétéroclite de partis, comprenant les kémalistes libéraux (CHP), les islamistes (SAADET), les anciens fonctionnaires d'Erdoğan Ali Babacan et Ahmet Davutoğlu avec leurs partis, et les nationalistes du Bon Parti (IYI). Outre ces structures politiques, qui se présentent également aux élections législatives sous la forme d'un bloc, l'Alliance nationale, la candidature de Kılıçdaroğlu aux élections présidentielles est également soutenue par le Parti démocratique des peuples kurde (HDP), qui est accusé d'avoir des liens avec le Parti des travailleurs du Kurdistan, un parti terroriste. La seule chose que toutes ces forces ont en commun est leur désir de renverser Erdogan à tout prix.

Repères en matière de politique étrangère

Dans sa campagne électorale, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan met en avant sa réussite à élever le rôle de la Turquie sur la scène internationale, à en faire un leader régional et à développer les infrastructures du pays. L'opposition, rassemblée autour de Kılıçdaroğlu, reproche aux autorités la détérioration de la situation économique de la Turquie, notamment ces dernières années, l'inflation et la dépréciation de la monnaie nationale, la livre turque.

L'opposition ne cache pas ses liens avec les Etats-Unis. Kılıçdaroğlu a récemment rencontré l'ambassadeur américain en Turquie, Geoffrey Flake. À l'automne dernier, il s'est rendu aux États-Unis, où il a disparu de la vue des journalistes pendant huit heures. On ne sait pas de quoi et avec qui il a discuté pendant cette période. Auparavant, le président américain Joe Biden avait ouvertement déclaré son intention d'évincer Recep Tayyip Erdogan lors des élections. Après les États-Unis, le principal rival d'Erdogan s'est rendu au Royaume-Uni pour y rencontrer des "investisseurs".

L'opposition espère une aide de l'Occident, notamment des pays anglo-saxons, dans le domaine économique. Si elle arrive au pouvoir, certaines positions géopolitiques de la Turquie pourraient devenir une monnaie d'échange.

En échange d'une aide financière et de la levée de certaines sanctions, Kılıçdaroğlu et son équipe pourraient opter pour une détérioration progressive des relations avec la Russie : en matière de sanctions anti-russes, de coopération technique et militaro-technique, de coordination des actions en Syrie, de corridor aérien vers la Syrie, d'assistance militaro-technique au régime de Zelenski.

Dans une interview accordée au Wall Street Journal le 9 mai dernier, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu a promis de se joindre aux sanctions anti-russes et de suivre la ligne de l'OTAN dans la politique étrangère du pays. Il ne faut pas oublier que l'équipe de Kılıçdaroğlu comprend Ahmed Davutoğlu (photo), l'architecte des politiques néo-ottomanes de la Turquie dans les années 2010, qui était premier ministre lors de la destruction tragique en 2015 d'un Su-25 russe dans le ciel de la Syrie. Les pilotes qui ont abattu l'avion ont agi sur ordre de Davutoğlu. Davutoğlu, malgré son néo-ottomanisme, est également un homme politique pro-américain.

Dans le même temps, les États-Unis n'ont pas utilisé tous les leviers à leur disposition pour soutenir l'opposition. Cela pourrait signifier qu'ils font pression sur l'équipe d'Erdogan en même temps, montrant qu'ils sont prêts à travailler avec eux aussi, mais en échange de certaines concessions.

Conséquences immédiates

À la veille de l'élection, chacune des parties en présence a fait savoir que, dans certaines circonstances, elle pourrait ne pas accepter les résultats. Suleyman Soylu, chef de la MIL turque, affirme que les États-Unis tentent d'interférer dans les élections turques. Pour sa part, Muharrem Erkek, adjoint de Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, a accusé Soylu lui-même d'avoir préparé le trucage. Une situation a été créée qui pourrait se transformer en une tentative de "révolution de couleur" ou, à tout le moins, en troubles de masse.

Une crise de pouvoir prolongée pourrait également se produire si une force politique remporte les élections présidentielles et une autre les élections législatives. Cela est possible dans une société divisée.

Si l'opposition turque l'emporte, il est fort probable que les divisions internes au sein d'un camp uni par le seul désir de se débarrasser d'Erdogan s'intensifieront. Les contradictions internes sont susceptibles de conduire à une scission et à des élections anticipées dans les six prochains mois. Il convient de noter que l'opposition, à l'exception de Babacan et Davutoğlu, n'a aucune expérience de la gestion d'un État depuis 20 ans. La Turquie a beaucoup changé sous le règne d'Erdogan. Il est probable qu'en l'absence d'une figure charismatique à la barre, ils ne seront pas en mesure de faire face à la gouvernance de l'État et de régler les différends internes, ce qui entraînera une aggravation des tendances à la crise en Turquie.

Les grâces accordées pour le coup d'État de 2016 inspiré par Fethullah Gulen, basé aux États-Unis, pourraient entraîner de graves problèmes internes et une détérioration des relations avec la Russie.

Kılıçdaroğlu avait précédemment promis "le soleil et le printemps" aux personnes renvoyées pendant les décrets relatifs à l'état d'urgence. Après la tentative de coup d'État de 2016, plus de 170.000 fonctionnaires et militaires, professeurs d'université et des centaines de médias et d'ONG ont été licenciés en Turquie en deux ans pour leurs liens avec l'organisation de Gulen. Des poursuites ont été engagées contre 128.000 personnes soupçonnées d'avoir participé au coup d'État.

Soutenir les participants au putsch, les gracier et les renvoyer de l'étranger, y compris à des postes gouvernementaux, alors que la Russie a joué un rôle clé dans l'échec du putsch en avertissant Erdogan de la tentative de coup d'État, pourrait conduire au renforcement d'une strate anti-russe au sein de l'élite dirigeante, des médias et des ONG de Turquie et à l'expansion des mécanismes de gouvernance externe dans le pays. À l'intérieur de la Turquie, une telle amnistie conduirait à un affrontement avec les opposants au putsch, qui sont descendus dans la rue en 2016 pour défendre le pays contre les gülenistes.

Cependant, la victoire d'Erdoğan et de son Parti de la justice et du développement (AKP) n'augure pas d'un redressement prochain du pays. Jusqu'à présent, les dirigeants turcs actuels ne montrent aucun signe de capacité à résoudre les problèmes économiques. Un autre problème pourrait être une crise de pouvoir au sein du parti. Le parti d'Erdogan est uni autour de son leader charismatique. Une détérioration significative de sa santé ces derniers temps pourrait entraîner une augmentation des tendances centrifuges au sein des "élites erdoganistes". Il existe déjà un "pôle patriotique" conditionnel représenté par le ministre de l'intérieur Suleyman Soylu, qui critique constamment les États-Unis, et un pôle axé sur le dialogue avec l'Occident représenté par le porte-parole d'Erdoğan, Ibrahim Kalın, et le ministre des affaires étrangères Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, qui ne cessent de parler de la loyauté de la Turquie à l'égard des engagements euro-atlantiques.

Il est clair que la Russie devra trouver une approche de ces élites au-delà de la relation personnelle entre le président Poutine et le président Erdogan. Toutes les voies possibles de communication et de rapprochement doivent être envisagées, à la fois sur la base d'intérêts pragmatiques et des vues idéologiques des personnages clés : l'antiaméricanisme (Soylu) et le traditionalisme (Kalın - en tant qu'adepte du philosophe René Guénon et des mystiques islamiques : Ibn Arabi et Mulla Sadr).

17:43 Publié dans Actualité, Politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, politique internationale, turquie, asie mineure, erdogan, élections turques, élections turques 2023, géopolitique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 20 avril 2023

Les élections en Turquie auront-elles un impact sur la place de ce pays dans un monde multipolaire ?

Les élections en Turquie auront-elles un impact sur la place de ce pays dans un monde multipolaire ?

Ceyda Karan

Source: https://katehon.com/en/article/will-turkiyes-elections-impact-its-place-multipolar-world?fbclid=IwAR0KrOHugXwmcJqAKhblX71bm5L1egKixOQ5hQ4pNet4SFLT6Yx1j-dMkJ8

Une victoire de l'opposition aux prochaines élections pourrait "occidentaliser" la politique étrangère de la Turquie et perturber le délicat exercice d'équilibre d'Ankara dans le nouvel ordre multipolaire.

Le 14 mai 2023, des élections très attendues, mais néanmoins cruciales, auront lieu en Turquie pour élire le président et les députés. Ces élections sont cruciales pour le président Recep Tayyip Erdogan, dont la réputation politique intérieure a été ternie par sa gestion du tremblement de terre du 6 février, aggravée par une crise économique de plus en plus grave au cours des deux dernières années.

Malgré les manœuvres pragmatiques visant à équilibrer l'Est et l'Ouest, la politique étrangère d'Erdogan est également critiquée. Non seulement le dirigeant turc de longue date est confronté à la plus grande épreuve de sa carrière politique, mais l'orientation future de la Turquie est également susceptible d'être remise en question.

Au cours des deux dernières semaines, plusieurs partis, dont le parti DEVA, le bon parti, le jeune parti, le parti de la libération du peuple, le parti de la gauche, le parti de la patrie et le parti de la résurrection, se sont opposés à la candidature d'Erdogan.

Cette objection a rallié les nationalistes, les socialistes, le centre-droit, les islamistes, les kémalistes et les "sept dissemblances" de la politique turque.

Le principal parti d'opposition, le Parti républicain du peuple (CHP), qui est le parti fondateur de la Turquie, n'a pas tenté de s'opposer à la candidature d'Erdogan.

Candidature d'Erdogan à un troisième mandat

D'éminents juristes expliquent qu'en vertu de l'article 101 de la Constitution turque, en vigueur depuis 2007, "une personne ne peut être élue président que deux fois au maximum". Erdogan a été élu en 2014 et en 2018, et il a déjà effectué deux mandats.

La seule exception à l'article 101 serait si le parlement décidait de renouveler les élections. Cependant, le parti Justice et Développement (AKP) d'Erdogan ne se réfère pas à la Constitution, mais au Conseil électoral suprême (YSK), dont les pouvoirs sont limités à l'administration générale et à la supervision des élections.

L'AKP affirme que les modifications techniques du "système de gouvernement présidentiel", introduites lors du référendum controversé de 2017 au cours duquel le YSK a reconnu les votes non scellés comme étant valides, rendent la candidature d'Erdogan possible. En d'autres termes, même si la Constitution reste en place, le premier mandat d'Erdogan ne compte pas.

Par le passé, Erdogan a déclaré "nous ne reconnaissons pas" les décisions de la Cour constitutionnelle. En fait, l'élection de la municipalité métropolitaine d'Istanbul, qui a battu son parti à plate couture en 2019, a été répétée sans aucune base juridique. Le résultat a été une défaite encore plus importante pour l'AKP.

En bref, le CHP a accepté la troisième nomination d'Erdogan sur la base de ses antécédents en matière de respect de la loi écrite. Le fait d'insister sur le contraire pourrait jouer dans le "récit de victimisation" qu'il a effectivement utilisé au cours des deux dernières décennies.

Le Conseil électoral suprême a récemment annoncé les candidats à la présidence qui s'affronteront le 14 mai :

Erdogan se présente en tant que candidat de l'"Alliance du peuple (Cumhur)", qui comprend l'AKP, le Parti du mouvement nationaliste (MHP), le Parti de la grande unité (BBP), le Nouveau parti de la prospérité (YRP) et l'HUDA-PAR.

Kemal Kilicdaroglu, quant à lui, se présente comme le candidat de l'"Alliance de la Nation (Millet)", qui comprend le CHP, le Bon Parti, le Parti de la Félicité (SAADET), le Parti Démocratique (DP), le Parti de la Démocratie et du Progrès (DEVA) et le Parti de l'Avenir (GP). Cette alliance électorale est également connue sous le nom de coalition de la "table des six".

Outre ces deux principaux rivaux, il y a deux autres candidats : Muharrem Ince et Sinan Ogan. Ince était le candidat commun de l'opposition en 2018, mais il a quitté le CHP après avoir perdu face à Erdogan, et il a maintenant fondé le Parti de la patrie.

Ogan, un ancien député, a été exclu du MHP, le partenaire d'Erdogan, en 2017 et se présente en tant que candidat de l'Alliance Ata, qui réunit quatre petits partis nationalistes et kémalistes de droite.

Erdogan est confronté à un défi de taille cette fois-ci, car les sondages donnent Kilicdaroglu en tête avec 2,5 à 5 points d'avance. La possibilité d'un second tour est également envisagée en raison du facteur Muharrem Ince.

Alliances inattendues

Bien que les petits partis disparates de la politique turque n'apprécient pas l'"Alliance nationale", ils soutiennent principalement Kilicdaroglu pour éjecter Erdogan après deux décennies de règne.

La principale opposition turque de la "Table des Six" a finalement réussi à s'unir derrière Kilicdaroglu après de douloureuses discussions, mais un facteur encore plus critique favorisant son éligibilité est le parti pro-kurde de la démocratie des peuples (HDP), qui soutient indirectement Kilicdaroglu (sous la menace d'être fermé) en ne présentant pas son propre candidat.

Les 9 à 13 % de voix du HDP sont particulièrement importants, car ils ont obligé Erdogan à élargir son alliance d'une manière surprenante.

Au début des années 2000, Erdogan et l'AKP ont émergé du "Parti du bien-être" de la Vision nationale de Necmettin Erbakan, qui avait été la marque de fabrique de l'islamisme turc au 20e siècle. Un an avant sa mort, Erbakan, un important mentor de l'actuel président turc, a critiqué Erdogan pour être "le caissier du sionisme".

Fin mars, son fils Fatih Erbakan, chef du Nouveau parti du bien-être, qu'il a fondé sur la base de l'héritage de son père, a refusé de rejoindre l'Alliance populaire d'Erdogan en invoquant des "principes", mais a capitulé peu après pour rejoindre son vieil ennemi. Cependant, le parti Felicity (SAADET), dont les racines se trouvent également dans la Vision nationale d'Erkaban père, s'est aligné sur l'Alliance nationale de Kilicdaroglu.

Mais l'initiative la plus frappante d'Erdogan pour élargir son alliance est venue du HUDA-PAR, que les experts politiques associent au "Hezbollah turc" ou "Hezbollah kurde", un mouvement soutenu par l'État qui a perpétré des attentats terroristes dans le sud-est de la Turquie à la fin des années 1980 et dans les années 1990.

"La philosophie, les convictions et les fondateurs [de l'HUDA-PAR] sont exactement les mêmes" que ceux du Hezbollah turc, déclare Hanefi Avci, chef de police à la retraite de renommée nationale. Ce dernier, dès sa création, a été officiellement désigné comme une organisation terroriste, et nombre de ses associations affiliées ont été systématiquement fermées. Parfois confondu avec l'organisation de résistance chiite libanaise Hezbollah, le mouvement turc est aux antipodes : il est au contraire fortement imprégné de l'idéologie des extrémistes religieux kurdes sunnites.

L'inclusion de l'HUDA-PAR dans l'alliance d'Erdogan a soulevé des questions au sein de l'opinion publique turque quant à ses motivations, les avis divergeant à ce sujet. Certains pensent qu'Erdogan tente de séduire les Kurdes religieux, tandis que d'autres voient dans son alliance avec ce parti très controversé un signe de son désespoir électoral. Le parti ne représentant pas un nombre significatif d'électeurs, on ne sait pas encore pourquoi le président turc s'est lancé dans une telle aventure.

Promesses populistes et manœuvres de politique étrangère

Les précédentes victoires électorales d'Erdogan étaient en grande partie dues à ses tactiques agressives, mais après 20 ans, cette approche n'est plus fiable. L'effondrement de la livre turque - déclenché par la décision d'Erdogan de réduire les taux d'intérêt fin 2021 sur la base de la règle islamique du "nas" - et l'inflation, qui a atteint 70 % et, officieusement, 140 %, sont des problèmes majeurs pour l'électeur turc moyen. Les tremblements de terre dévastateurs qui ont eu lieu le 6 février ont encore plus déstabilisé l'économie turque.

Pour tenter de regagner des soutiens, Erdogan axe sa campagne sur des promesses de reconstruction. Il a mis en œuvre des politiques économiques populistes telles que l'augmentation du salaire minimum, qui est la principale source de revenus pour environ 60 % des Turcs, et l'augmentation des salaires des fonctionnaires et des pensions.

Erdogan est connu pour sa capacité à utiliser habilement la politique étrangère de la Turquie comme un outil pour atteindre des objectifs de politique intérieure et extérieure. Toutefois, ces dernières années, les perspectives économiques de la Turquie ont mis à mal les calculs de politique étrangère d'Erdogan.

Depuis l'effondrement des projets néo-ottomans soutenus par les États-Unis en Asie occidentale et en Afrique du Nord, Erdogan a cherché des approches plus pragmatiques qui donnent la priorité à la realpolitik plutôt qu'à l'idéologie. Le président turc a fait marche arrière sur un certain nombre de questions, notamment la réconciliation avec les dirigeants régionaux qu'il a publiquement dénigrés et l'adoption d'une position neutre dans la crise ukrainienne entre les États-Unis et la Russie.

Les efforts d'Erdogan ont parfois eu des effets positifs immédiats : En améliorant leurs relations avec l'Arabie saoudite et les Émirats arabes unis, les deux pays ont investi des milliards de dollars en Turquie, même si les détails de ces accords restent flous.

Erdogan a également fait amende honorable avec le président égyptien Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, qu'il avait précédemment accusé d'avoir orchestré un coup d'État contre le gouvernement élu dirigé par les Frères musulmans. Ces réconciliations ont donné lieu à des négociations sur des questions liées à la confrérie et à la Libye.

Les défis de la politique étrangère d'Erdogan

Les relations avec la Russie et la Syrie restent toutefois deux des questions les plus épineuses pour Ankara, principalement parce qu'elles placent la Turquie dans le collimateur des principaux objectifs de politique étrangère de Washington.

Les intérêts en jeu sont on ne peut plus clairs : la Turquie dépend de la Russie pour l'énergie et le tourisme, tandis que la Russie a besoin de la Turquie pour atténuer l'impact des sanctions américaines.

Malgré les efforts de pragmatisme d'Erdogan en matière de politique étrangère, ses tentatives de réconciliation avec le dirigeant syrien Bashar al-Assad se sont enlisées en raison des objections des États-Unis et des conditions posées par Damas. Bien qu'Erdogan ait fait part de sa volonté de se réconcilier avec Assad en novembre dernier, la question n'a pas beaucoup progressé, malgré des réunions de haut niveau entre leurs responsables, sous la médiation de la Russie.

Les ministres de la défense turc et syrien se sont rencontrés à Moscou en décembre 2022, et si leurs vice-ministres des affaires étrangères respectifs se sont brièvement rencontrés les 3 et 4 avril, les réunions officielles de haut niveau ne se sont pas encore concrétisées. C'est le signe que la volonté politique ou les conditions de terrain ne sont pas encore réunies pour accélérer la diplomatie, d'un côté comme de l'autre.

Cela est dû en grande partie à la ligne rouge syrienne qui exige l'évacuation de toutes les troupes turques du sol syrien avant que les pourparlers de rapprochement ne progressent. Pourtant, lors d'une réunion avec son homologue russe Sergey Shoigu, le ministre turc de la défense Hulusi Akar a encore affirmé que la présence militaire turque en Syrie était destinée à la "lutte contre le terrorisme", au "maintien de la paix" et à l'"aide humanitaire".

Certains commentateurs estiment qu'il sera difficile pour l'armée turque de se retirer de Syrie et de satisfaire aux conditions d'Assad en raison de l'activité continue des milices séparatistes kurdes dans le nord du pays et des problèmes posés par les organisations islamistes radicales soutenues par la Turquie à Idlib.

Même la rhétorique d'Erdogan sur le rapatriement des trois millions de réfugiés syriens a perdu de sa crédibilité en raison de l'emploi de cette main-d'œuvre bon marché par des chefs d'entreprise liés à l'AKP. Tous ces facteurs font qu'il est de plus en plus difficile pour Erdogan de réussir sa politique étrangère avant les élections de mai.

Engin Solakoglu, diplomate turc à la retraite, explique à The Cradle que si l'AKP a pu étendre l'autonomie de sa politique étrangère en raison de l'affaiblissement de l'influence régionale des États-Unis, il opère toujours dans le cadre des relations existantes de la Turquie avec l'Occident : "Les fonds dont l'économie turque a chroniquement besoin proviennent principalement des centres financiers européens", explique-t-il.

Selon le professeur Behlul Ozkan, si les pays de taille moyenne comme la Turquie ont la capacité d'agir parfois de manière indépendante en matière de politique étrangère, la vision du monde d'Erdogan ne penche pas vers l'eurasisme, comme le prétendent souvent les experts occidentaux et orientaux.

Ozkan souligne le rôle important joué par l'Occident dans l'économie turque au cours des deux dernières décennies :

"Si Erdogan et l'AKP remportent les élections, il est fort possible que la Turquie devienne encore plus dépendante de l'Occident pour sortir de sa crise économique. Le rôle de l'AKP pour la Turquie est d'être le gendarme de l'Occident dans la région, comme il l'était pendant la guerre froide".

La vision du monde de l'opposition

Au lieu de tirer parti des contraintes et des vulnérabilités d'Erdogan en matière de politique étrangère, l'opposition multipartite a présenté un "protocole d'accord commun" peu convaincant, qui n'aborde guère son programme extérieur. Plus de platitudes que de substance, l'opposition met l'accent sur un principe de "paix à la maison, paix dans le monde" et affirme que l'intérêt national et la sécurité seront à la base de ses politiques.

Le document indique également que "les relations avec les États-Unis devraient être institutionnalisées dans le cadre d'une entente entre égaux", alors que la Russie n'est mentionnée qu'à deux reprises. Il convient également de noter que le CHP a récemment rappelé à Moscou que la Turquie est "un pays de l'OTAN".

Selon Hazal Yalin, chercheur et écrivain spécialisé dans les affaires russes, l'incapacité de la bourgeoisie turque à rompre les liens avec l'impérialisme occidental rend difficile la communication de l'opposition turque avec la Russie. Comme il l'explique à The Cradle :

"La Russie a la possibilité de poursuivre ses relations interétatiques avec la Turquie, comme avec n'importe quel autre pays, quel que soit le parti au pouvoir ; par conséquent, dans l'éventualité d'un changement de pouvoir, elle peut faire comme si rien ne s'était passé".

Malgré la possibilité que l'alliance d'opposition poursuive des politiques plus orientées vers l'Occident, le professeur Ozkan pense qu'elle adoptera une approche plus pacifique dans la région par rapport à l'AKP :

"L'établissement de relations diplomatiques avec la Syrie est la première priorité. La présence militaire turque en Syrie sera progressivement réduite, probablement en contact avec d'autres puissances régionales, et l'intégrité territoriale sera restaurée en coopération avec Damas".

Ozkan ajoute : "Il n'est pas possible de prendre une décision :

"Il n'est pas possible de prendre une mesure similaire avec l'AKP. Tant que l'AKP restera au pouvoir, il voudra maintenir sa présence militaire et la poursuite du conflit en Syrie comme monnaie d'échange avec l'Occident et la Russie, et en tirer profit."

Certaines choses ne changeront jamais

Toutefois, M. Solakoglu, diplomate à la retraite, estime que même si l'opposition l'emporte, il est peu probable qu'elle renonce à l'autonomie en matière de politique étrangère acquise sous le régime de l'AKP :

"Je ne pense pas que la présence militaire en Syrie, en Irak et en Libye disparaîtra soudainement. De même, je ne pense pas que le gouvernement Kilicdaroglu adoptera une position [différente] en Méditerranée orientale, sur la question de la 'patrie bleue' et sur Chypre. Sur ces questions, ils sont les mêmes que l'AKP. "

Le professeur Baris Doster ne prévoit pas de changement significatif dans les politiques d'Erdogan, malgré son nouveau pragmatisme. "Si l'opposition gagne les élections", dit-il, "les réalités et les relations économiques de la Turquie continueront à ralentir même si elle veut se tourner vers l'ouest".

Quel que soit le résultat des élections, il est peu probable que la Turquie rompe ses liens avec l'Occident. Alors que certains affirment qu'Ankara devrait s'adapter à la tendance mondiale multipolaire, la Turquie est toujours un membre à part entière de l'alliance militaire de l'OTAN, ce qui créera certainement des obstacles à l'adhésion à l'Organisation de coopération de Shanghai (OCS) dirigée par la Chine - comme Erdogan a périodiquement menacé de le faire.

Mais cela n'empêche pas la Turquie de rejoindre les BRICS+ élargis, l'initiative chinoise Belt and Road (BRI), les institutions économiques eurasiatiques et/ou les mégaprojets de connectivité terre-rail-eau. La question est de savoir si les prochaines élections - quels que soient leurs résultats - peuvent mettre sur la touche ou réorienter la multipolarité qui a déjà balayé toutes les institutions turques.

20:02 Publié dans Actualité, Politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, politique, politique internationale, turquie, erdogan, asie mineure, élections turques 2023 |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 21 mars 2023

Erdogan face à l'épreuve ultime

Erdogan face à l'épreuve ultime

Alexandre Douguine

Note du traducteur : Alexandre Douguine analyse ici la situation en Turquie du point de vue russe et dans le cadre actuel de la guerre entre la Russie et l'Ukraine (ou plutôt entre la Russie et l'OTAN) en mer Noire, enjeu de la vieille rivalité russo-ottomane. La situation actuelle implique un changement d'approche significatif. Pour l'Europe (ou pour l'idée de Maison commune), la nécessité d'accepter les arguments d'Erdogan, qui souhaite limiter l'ingérence américaine, va de pair avec un rejet de la politique d'Erdogan consistant à manipuler la diaspora turque contre les sociétés européennes, une manipulation qui aurait lieu même si la marque idéologique notoire des régimes d'Europe occidentale n'était pas le wokisme.

En Turquie, la date des élections présidentielles a été annoncée. Il s'agira probablement de l'épreuve la plus difficile pour Erdogan jusqu'à présent et sur le plan intérieur -avec le renforcement de l'opposition néolibérale pro-occidentale (en particulier le Parti républicain du peuple), une scission au sein du Parti de la justice et du développement (AKP) lui-même, un grave ralentissement économique, l'inflation, les conséquences d'un monstrueux tremblement de terre. Sur le front extérieur, avec l'intensification du conflit avec les États-Unis et l'Union européenne et le rejet de plus en plus marqué des politiques d'Erdogan par les dirigeants mondialistes de la Maison Blanche.

Lutte pour la souveraineté

L'aspect principal de la politique d'Erdogan est l'importance qu'elle accorde à la souveraineté. C'est le point central de sa politique. Toutes ses activités en tant que chef d'État s'articulent autour de cet axe. Dans un premier temps, Erdogan s'est appuyé sur l'idéologie islamiste, une alliance avec les régimes salafistes sunnites extrêmes du monde arabe. Durant cette période, il a collaboré très étroitement avec les Etats-Unis, les structures de Fethullah Gulen servant de charnière dans cette coopération. Les kémalistes laïques, les nationalistes turcs, de gauche comme de droite, étaient alors dans l'opposition. Cela a culminé avec l'affaire Ergenekon, dans laquelle Erdoğan a arrêté l'ensemble du haut commandement militaire, qui adhérait traditionnellement à l'orientation kémaliste.

À un moment donné, cette politique a cessé de promouvoir la souveraineté et a commencé à l'affaiblir. Après l'opération militaire russe en Syrie et le crash de l'avion turc en 2015, Erdoğan a été menacé : premièrement, les relations avec la Russie se sont détériorées, amenant la Turquie au bord de la guerre ; deuxièmement, l'Occident, insatisfait de la politique de souveraineté, était prêt à renverser Erdoğan et à le remplacer par des collaborateurs plus obéissants - Davutoğlu, Gül, Babacan, etc. Les gülenistes, anciens alliés d'Erdoğan et principaux opposants au kémalisme, sont devenus la colonne vertébrale du complot.

En 2016, alors que les relations avec la Russie se sont quelque peu clarifiées, l'Occident, en s'appuyant sur les fethullahistes (gülenistes), a tenté d'organiser un coup d'État, qui a toutefois été déjoué. Le fait qu'un nombre important de kémalistes patriotes, d'officiers militaires libérés par Erdogan peu avant le coup d'État, et leur structure politique, le parti Vatan, aient soutenu Erdogan plutôt que les militaires pro-occidentaux au moment critique a été un facteur décisif. Le fait est qu'à ce stade, les nationalistes kémalistes (de gauche comme de droite) avaient compris qu'Erdogan construisait sa politique sur le renforcement de la souveraineté et que l'idéologie était secondaire pour lui.

Étant donné que les conspirateurs gülenistes et les autres Occidentaux qui se sont rebellés contre Erdoğan suivaient servilement l'Occident mondialiste, ce qui conduisait inévitablement la Turquie à un effondrement total et à l'élimination de l'État-nation, les kémalistes ont décidé de soutenir Erdoğan pour sauver l'État. La Russie a également soutenu en partie Erdogan, réalisant que ses ennemis étaient des marionnettes de l'Occident. Les nationalistes turcs du Parti du mouvement nationaliste (MHP) ont également fini par se ranger à ses côtés.

Depuis 2016, Erdoğan a embrassé des positions proches du kémalisme patriotique et en partie de l'eurasisme, proclamant ouvertement la priorité de la souveraineté, critiquant l'hégémonie occidentale et prônant un projet de monde multipolaire. Les relations avec la Russie se sont également progressivement améliorées, bien qu'Erdoğan ait occasionnellement fait des gestes pro-occidentaux. Désormais, la souveraineté est devenue son idéologie et son objectif politique le plus élevé.

Cependant, l'opposition libérale sous la forme du Parti républicain du peuple (Kılıçdaroğlu - photo), qui s'est d'abord opposée à la ligne islamiste du premier Erdoğan et a ensuite rejeté la souveraineté, a exploité une série d'erreurs de calcul sur le plan intérieur et économique. Il est parvenu à obtenir un certain nombre de postes clés lors des élections, notamment en présentant ses propres candidats à la mairie des deux principales villes, Ankara et Istanbul. Erdoğan s'est également heurté à l'opposition de ses anciens collègues du parti AKP au pouvoir, qui sont également opposés à l'eurasisme et à la souveraineté et orientés vers l'Occident - les mêmes Ahmet Davutoğlu, Abdullah Gül, Ali Babacan, etc.

C'est dans cette situation qu'Erdogan se rendra bientôt aux urnes. L'Occident est manifestement mécontent de lui en raison de sa désobéissance - en particulier sa démarcation contre la Suède et la Finlande, dont la Turquie a empêché l'adhésion à l'OTAN ; la politique relativement indulgente d'Ankara à l'égard de la Russie, contre laquelle l'Occident collectif mène une guerre en Ukraine, a encore irrité les mondialistes de Washington et, surtout, les dirigeants modernes de la Maison Blanche et les élites mondialistes de l'Union européenne n'acceptent catégoriquement pas le moindre soupçon de souveraineté de la part de leurs vassaux ou de leurs adversaires.

Quiconque est prêt à se soumettre à l'Occident doit renoncer totalement à sa souveraineté en faveur d'un centre de décision supranational. Telle est la règle. Les politiques d'Erdogan la contredisent directement, c'est pourquoi Erdogan doit être démis de ses fonctions, à n'importe quel prix. Si l'Occident globalitaire a échoué dans le coup d'État de 2016, il devra tenter de renverser Erdogan lors des élections de 2023, quel qu'en soit le résultat. Après tout, il y a toujours la pratique des révolutions colorées en réserve.

C'est exactement ce que nous avons vu à nouveau en Géorgie, dont les dirigeants, après le départ de l'ultra-occidental et libéral Saakashvili, ont essayé de rendre la Géorgie un peu plus souveraine. Mais cela a suffi à Soros pour activer ses réseaux et lancer une révolte contre l'attitude "trop modérée" à l'égard de la Russie et l'orientation "inacceptablement souveraine" du régime contrôlé par l'oligarque pragmatique Bedzina Ivanishvili.

Erdogan est en train de constituer une coalition politique sur laquelle il pourra compter lors des élections. La colonne vertébrale sera évidemment l'AKP, un parti largement fidèle à Erdogan, mais sans substance et composé de fonctionnaires peu enthousiastes. Techniquement, c'est un outil utile, mais en partie embarrassant. En Turquie, nombreux sont ceux qui attribuent les échecs de l'économie, le développement de la corruption et l'inefficacité du système gouvernemental aux responsables de l'AKP et aux cadres administratifs nommés en leur sein. Si Erdoğan est une figure charismatique, l'AKP ne l'est pas. Le parti prospère grâce à l'autorité d'Erdogan, et non l'inverse.

Alliés et adversaires d'Erdogan

Les alliés traditionnels seront évidemment les nationalistes turcs du parti Mouvement nationaliste turc de Devlet Bahçeli (photo). Pendant la guerre froide et par inertie dans les années 1990, les nationalistes turcs étaient strictement orientés vers l'OTAN et poursuivaient une ligne antisoviétique (puis antirusse). Dans les années 2000, cependant, leurs politiques ont progressivement commencé à changer. Ils se sont de plus en plus éloignés de l'Occident libéral et se sont rapprochés du vecteur souverain d'Erdogan. Idéologiquement, ils sont plus flamboyants que l'AKP, mais leur radicalisme leur aliène une partie de la population turque. En tout état de cause, l'alliance idéologique et politique avérée d'Erdogan avec Bahçeli est cruciale pour son avenir.