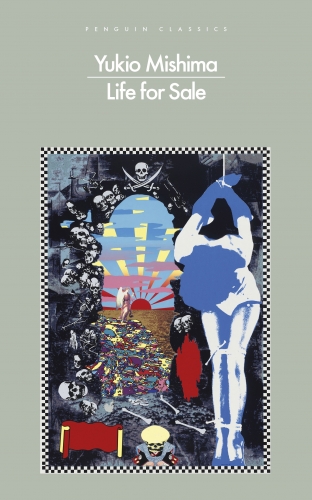

Yukio Mishima

Life for Sale

Translated by Stephen Dodd

London: Penguin Books, 2019

This past year has seen three new English translations of novels by Yukio Mishima: The Frolic of the Beasts, Star, and now Life for Sale, a pulpy, stylish novel that offers an incisive satire of post-war Japanese society.

Mishima’s extensive output includes both high-brow literary and dramatic works (jun bungaku, or “pure literature”) and racy potboilers (taishu bungaku, or “popular literature”). Life for Sale belongs to the latter category and will introduce English readers to this lesser-known side of Mishima. Despite being a popular novel, though, it broaches serious themes that can also be found in Mishima’s more sophisticated works.

27-year-old Hanio Yamada, the protagonist, is a Tokyo-based copywriter who makes a decent living and leads a normal life. But his work leaves him unfulfilled. He later remarks that his job was “a kind of death: a daily grind in an over-lit, ridiculously modern office where everyone wore the latest suits and never got their hands dirty with proper work” (p. 67). One day, while reading the newspaper on the subway, he suddenly is struck by an overwhelming desire to die. That evening, he overdoses on sedatives.

27-year-old Hanio Yamada, the protagonist, is a Tokyo-based copywriter who makes a decent living and leads a normal life. But his work leaves him unfulfilled. He later remarks that his job was “a kind of death: a daily grind in an over-lit, ridiculously modern office where everyone wore the latest suits and never got their hands dirty with proper work” (p. 67). One day, while reading the newspaper on the subway, he suddenly is struck by an overwhelming desire to die. That evening, he overdoses on sedatives.

When his suicide attempt fails, Hanio comes up with another idea. He places the following advertisement in the newspaper: “Life for Sale. Use me as you wish. I am a twenty-seven-year-old male. Discretion guaranteed. Will cause no bother at all” (p. 7). The advertisement sets in motion an exhilarating series of events involving adultery, murder, toxic beetles, a female “vampire,” a wasted heiress, poisonous carrots, espionage, and mobsters.

In one episode, Hanio is asked to provide services for a single mother who has already gone through a dozen boyfriends. It turns out that the woman has a taste for blood. Every night, she cuts Hanio with a knife and sucks on the wound. She occasionally takes Hanio on walks, keeping him bound to her with a golden chain. Hanio lives with the woman for a while, and her son remarks, rather poignantly, that the three of them could be a family. The scene calls to mind the modern Japanese practice of “renting” companions and family members.

By the end of the vampire gig, Hanio is severely ill and on the verge of death. Yet he is entirely indifferent to this fact: “The thought that his own life was about to cease cleansed his heart, the way peppermint cleanses the mouth” (p. 83). His existence is bland and meaningless, devoid of both “sadness and joy.”

When Hanio returns to his apartment to pick up his mail, he finds a letter from a former classmate admonishing him for the advertisement:

What on earth do you hope to attain by holding your life so cheaply? For an all too brief time before the war, we considered our lives worthy of sacrifice to the nation as honourable Japanese subjects. They called us common people “the nation’s treasure.” I take it you are in the business of converting your life into filthy lucre only because, in the world we inhabit, money reigns supreme. (p. 79)

With the little strength he has remaining, Hanio tears the letter into pieces.

Hanio survives the vampire episode by the skin of his teeth and wakes up in a hospital bed. He has scarcely recovered when two men burst into his room asking him to partake in a secret operation. After the ambassador of a certain “Country B” steals an emerald necklace containing a cipher key from the wife of the ambassador of “Country A” (strongly implied to be England), the latter ambassador has the idea of stealing the cipher key in the possession of the former. The ambassador of Country B is very fond of carrots, and it is suspected that his stash of carrots is of relevance. Three spies from Country A each steal a carrot, only to drop dead. All but a few of the ambassador’s carrots were laced with potassium cyanide, and only he knew which ones were not. It takes Hanio to state the obvious: any generic carrot would have done the trick, meaning that the spies’ deaths were in vain.

Like Hanio’s other adventures, it is the sort of hare-brained caper one would expect to find in manga. Perhaps Mishima is poking fun at the ineptitude of Western democracies, or Britain in particular. (I am reminded of how Himmler allegedly remarked after the Gestapo tricked MI6 into maintaining radio contact that “after a while it becomes boring to converse with such arrogant and foolish people.”)

After the carrot incident, Hanio decides to move and blurts out the first destination that comes to mind. He ends up moving in with a respectable older couple and their errant youngest child, Reiko. Reiko’s parents are traditionalists who treat him with “an almost inconceivable degree of old-fashioned courtesy” (p. 122). The father reads classical Chinese poetry and collects old artifacts, among them a scroll depicting the legend of the Peach Blossom Spring. Reiko, meanwhile, spends her days doing drugs and hanging out with hippies in Tokyo. She is in her thirties, but she acts like a young girl. Although her parents are traditionally-minded, they bend to her every whim and do not discipline her.

It is explained that Reiko’s would-be husband turned her down out of a mistaken belief that her father had syphilis. Bizarrely, Reiko has convinced herself that she inherited the disease and that she will die a slow and painful death. Her death wish (combined with her parents’ negligence) appears to be the cause of her self-destructive behavior. She dreams of losing her virginity to a young man who would be willing to risk death by sleeping with her. Yet her fantasies turn out to be rather domestic. She play-acts a scene in which she tells an imaginary son that his father will be coming home at 6:15, as he does everyday.

This reminds Hanio of his former life as a copywriter and suddenly causes him to realize that the scourge of the city is palpable even in the cloistered confines of the tea house in which he is staying: “Out there, restless nocturnal life continued to pulse. . . . Such was the hell that bared its fangs and whirled around Hanio and Reiko’s comfortable little tomb” (pp. 147-48).

Hanio makes his escape one night when Reiko takes him to the disco. At the end of the novel, he visits a police station and asks for protection from some mobsters who want him dead (long story). The police dismiss him as delusional and cast him out. He is left alone, gazing at the night sky.

Underneath the campy pulp-fiction tropes, Life for Sale is a sincere meditation on the meaningless and absurdity of modern urban life. Surrendering one’s life is the most convenient escape from such an existence. The only alternative is to identify a higher purpose and pursue it relentlessly—after the manner of Mishima himself.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.