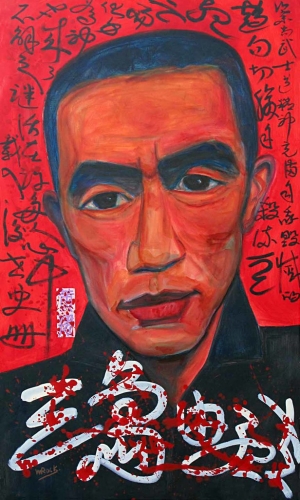

Yukio Mishima - samouraï, monarchiste, révolutionnaire conservateur

Ronald Lasecki

Source: https://ronald-lasecki.blogspot.com/2023/10/yukio-mishima-samuraj-monarchista.html

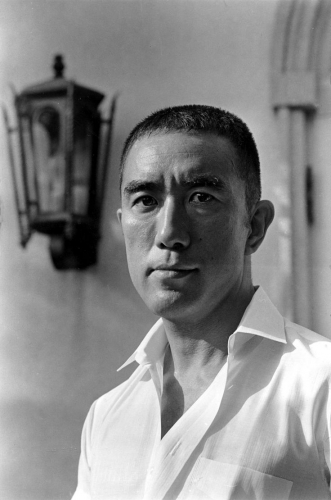

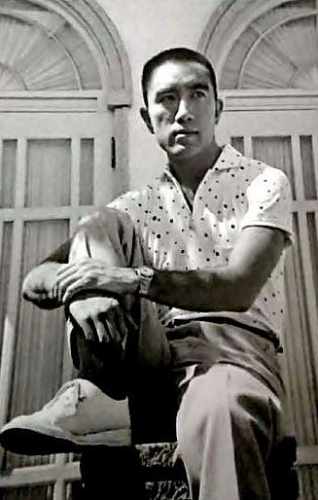

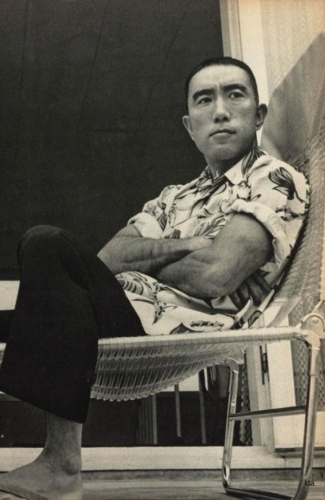

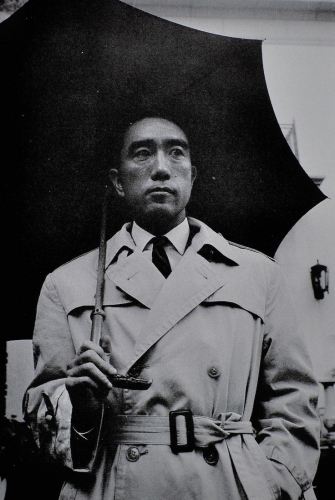

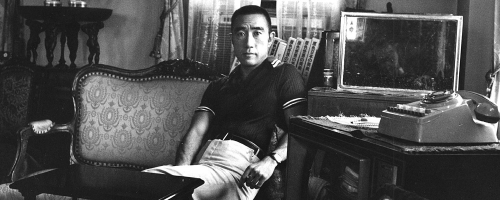

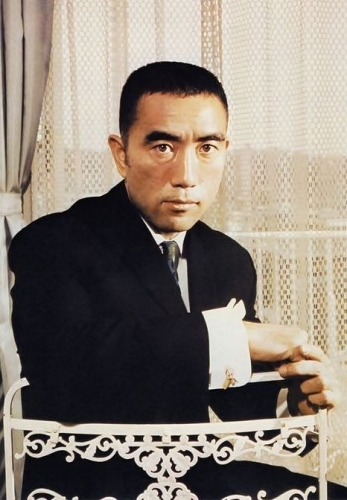

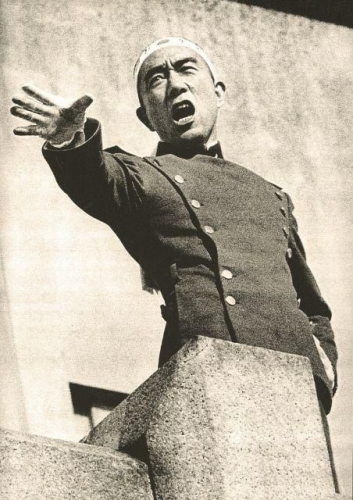

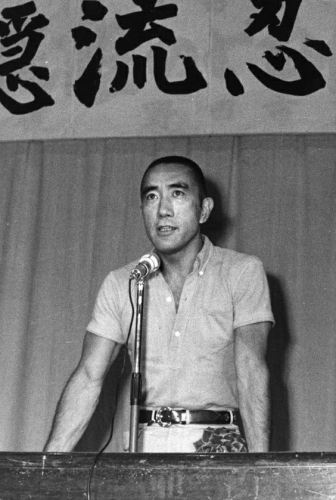

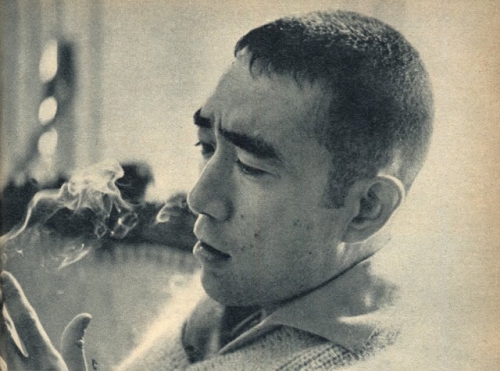

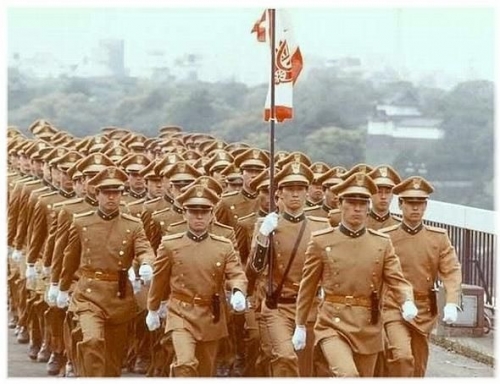

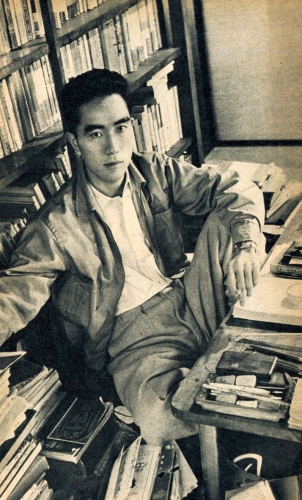

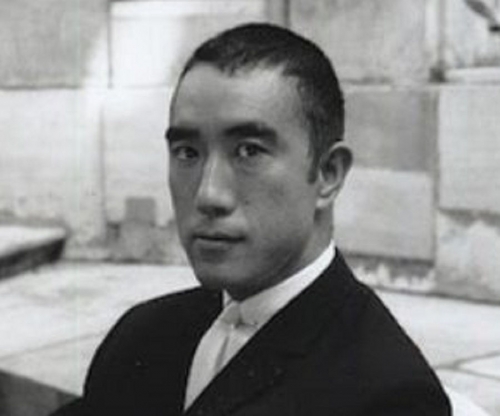

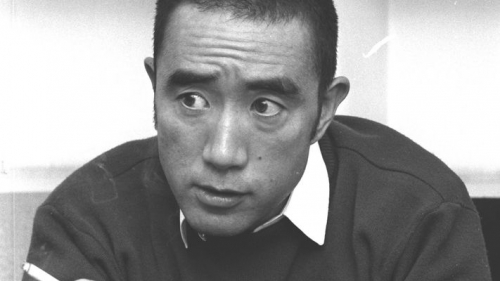

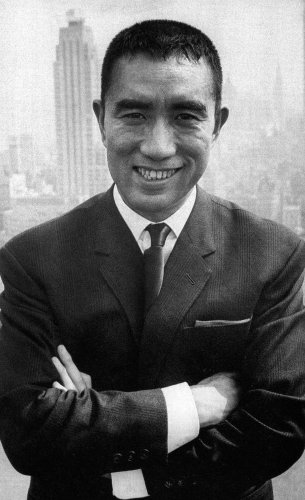

L'écrivain et militant nationaliste japonais Yukio Mishima (1925-1970) est populaire, y compris dans les milieux de droite (1), principalement pour son extraordinaire acte de suicide rituel de samouraï (seppuku), commis le 25 novembre 1970, après que lui-même et quatre autres membres de l'Association nationaliste du bouclier (Tate no Kai), qu'il avait fondée deux ans plus tôt, se soient emparés du bureau du général Kanetoshi Mashita, commandant du commandement oriental des forces d'autodéfense japonaises (Jieitai), qui avait été capturé et avait été tué par des soldats. Kanetoshi Mashita avait été le chef du commandement oriental des forces japonaises d'autodéfense (Jieitai) à Tokyo (2).

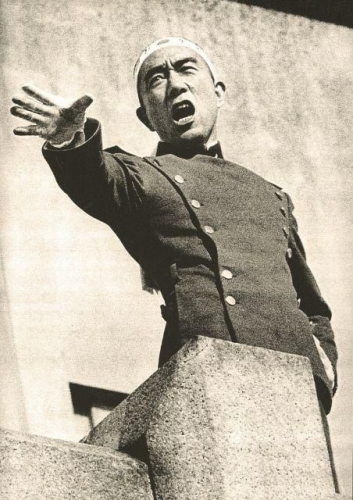

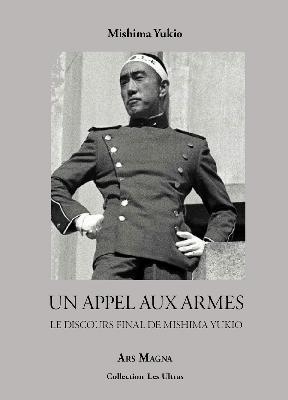

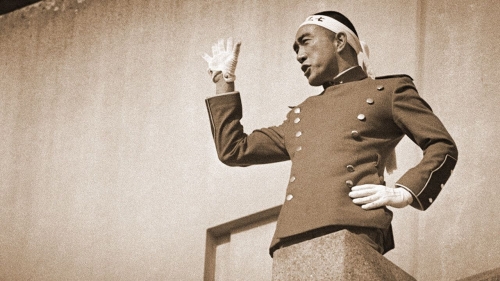

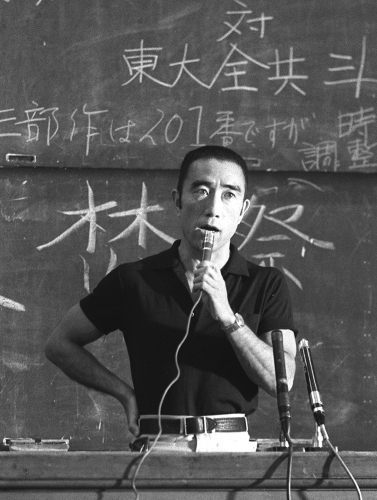

Dans un discours prononcé depuis le balcon du bâtiment de la garnison devant les soldats rassemblés sur la place en contrebas (qui avaient été convoqués là sous la menace d'une exécution par les assassins du commandant), Y. Mishima demande une révision de l'article 9 de la constitution imposée sous l'occupation par les Yankees le 3 novembre 1946, qui stipule que le Japon renonce à jamais à la guerre en tant que droit souverain de la nation, ainsi qu'à l'usage ou à la menace de la force comme moyen de règlement des différends internationaux. Dans le paragraphe suivant du même article, le Japon déclare qu'il ne se reconnaît pas le droit de faire la guerre et qu'il ne maintiendra jamais de forces armées terrestres, maritimes ou aériennes, ni aucun autre moyen capable de faire la guerre (3).

Le discours de Y. Mishima est moqué par les soldats rassemblés et, après l'avoir terminé au bout de quelques minutes en criant trois fois "Vive l'empereur !", il retourne dans son bureau et se fait seppuku. Si le discours de Tate no Kai a pu bénéficier du soutien tacite de certains cercles de commandement du Jieitai qui envisageaient de réviser la constitution et de reconstruire l'armée japonaise, le soutien de l'action de Y. Mishima a été, en fait, un soutien tacite de l'armée japonaise. L'action de Mishima a cependant été entravée par le changement de politique américaine à l'égard de la Chine initié en 1969 par Henry Kissinger, à la suite duquel la remilitarisation du Japon n'a pas eu les faveurs de Washington à l'époque et l'éventuel retrait des militaires japonais aurait eu lieu sans les sanctions de l'USFJ (United States Forces Japan). Un facteur destiné à favoriser le groupe de Y. Mishima et à radicaliser le discours de Jieitai furent également les émeutes déclenchées dans les universités par le Comité de grève combiné des étudiants (Zenkyoto), qui furent toutefois traitées de manière indépendante par des unités de la police d'assaut.

Les problèmes de militarisation du Japon

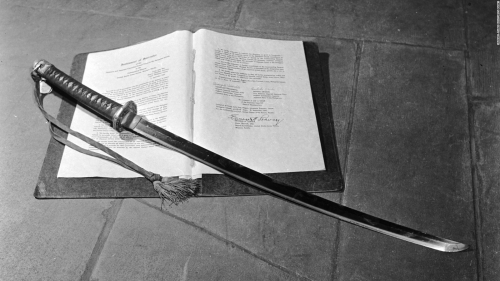

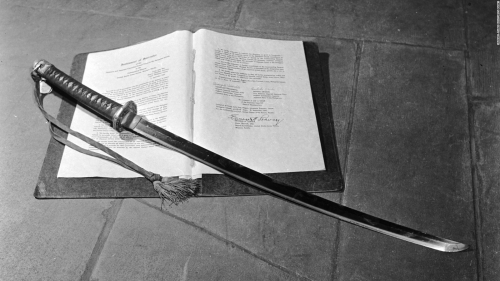

La question de la militarisation du Japon et de son droit à mener des opérations militaires était en fait déjà devenue un sujet de controverse politique récurrent à Tokyo depuis la capitulation signée le 2 septembre 1945 à bord du navire yankee "Missouri" amarré dans la baie de Tokyo. Le déclenchement de la guerre dans la péninsule coréenne a incité les Yankees à créer une force de police de réserve japonaise autochtone de 75.000 fonctionnaires en 1950, à renforcer la force de défense côtière, laquelle devait également être japonaise et autochtone, et à révoquer l'interdiction de la production de matériels militaires au Japon. Le traité de paix avec le Japon, signé à San Francisco le 8 septembre 1951, stipule que le pays a le droit de se défendre individuellement et collectivement, conformément à l'article 51 de la Charte des Nations unies (4).

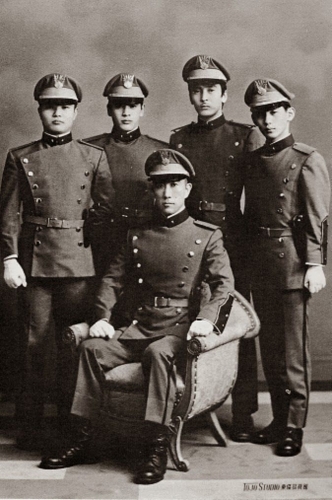

Soldats japonais en 1955.

Le traité de sécurité entre les États-Unis et le Japon, signé le même jour, sanctionnait le stationnement indéfini de troupes américaines dans l'archipel, avec la possibilité qu'elles soient utilisées à la fois pour défendre le Japon contre une attaque extérieure, pour réprimer les troubles internes dans le pays et pour des opérations dans la région élargie de l'Extrême-Orient. En 1952, les troupes de police de réserve ont été transformées en troupes de sécurité et, en 1954, les troupes d'autodéfense (Jieitai) ont été créées avec un effectif de 152.000 hommes. Cependant, les Jieitai ne peuvent être utilisées qu'à l'intérieur du Japon. Le 19 janvier 1960, une nouvelle version du traité de sécurité avec les États-Unis a été signée, qui comprenait une disposition selon laquelle le Japon devait fournir une assistance armée aux forces yankees en cas de combats sur son territoire (5).

Ni le Premier ministre "faucon" Nakasone Yasuhiro (1982-1986), ni Shinzo Abe, le plus ancien Premier ministre japonais de l'après-guerre (2006-2007, 2012-2020), n'ont réussi à réviser le malheureux article 9 de la Constitution. "(...) le Premier ministre n'a pas réussi à réaliser son projet le plus important, qui était de réviser la Constitution du Japon et de donner des pouvoirs légaux à la Force japonaise d'autodéfense. Cependant, sous le gouvernement Abe, un certain nombre de changements ont été apportés concernant la sécurité intérieure du Japon et les réglementations qui permettent aux troupes japonaises d'être déployées à l'extérieur du pays. Sous le gouvernement du Premier ministre Abe, le Japon a considérablement augmenté ses dépenses d'armement, ce qui devait aboutir à l'installation d'un système de bouclier terrestre de défense antimissile". Un expert polonais du Japon a écrit un essai intéressant à propos de la démission du Premier ministre japonais, annoncée le 16 septembre 2020 (6).

Le nouveau Premier ministre Suga Yoshihide est considéré comme moins expérimenté que son prédécesseur en matière de politique étrangère et de sécurité et moins intéressé par ces questions. Le Parti libéral démocrate (PLD), parti conservateur du Japon, actuellement au pouvoir, envisage d'équiper les forces d'autodéfense de missiles à longue portée capables de dissuader une attaque de missiles balistiques alors qu'ils se trouvent encore en territoire ennemi et d'habiliter le Jieitai à lancer des attaques préventives (la Corée du Nord et la Chine sont considérées comme des adversaires, en raison du conflit croissant avec cette dernière au sujet de l'archipel des Senkaku, en mer de Chine orientale). En juillet 2020, le ministère japonais de la défense présente à son tour un projet visant à remplacer le chasseur F-2 produit par Mitsubishi Heavy Industries par un nouveau modèle de chasseur japonais. En septembre 2020, un nouveau budget militaire est adopté, qui atteint le montant record de 51,8 milliards d'USD. Les plans de dépenses comprennent la construction d'un nouveau système de défense antimissile installé sur les navires de guerre. Cependant, l'opposant à la révision de l'article 9 de la constitution reste le parti Komeito, qui est en coalition avec le PLD, et sans nouvelles élections générales, le Premier ministre S. Yoshihide n'obtiendra pas de majorité parlementaire pour un tel projet (7).

Selon Y. Mishima, le plus important pour le peuple japonais est de sortir de la pensée pacifiste en adoptant une nouvelle constitution à l'image d'un Etat souverain. Tel est le message de Y. Mishima devant la garnison Jieitai de la capitale en novembre 1970, et c'est à cette idée que le nationaliste japonais a consacré ses activités politiques et formatrices, qui ont abouti à son suicide ce jour-là. Selon Y. Mishima, la constitution d'occupation du Japon a conduit le pays à effacer l'esprit national, l'a abruti par un pacifisme outrancier, l'a transformé en une puissance purement économique et financière sans cervelle et sans âme, ce qui doit finalement conduire à l'autodestruction du Japon. Il convient de noter ici que la bulle de croissance économique du Japon a effectivement éclaté dans les années 80, aggravée par l'effondrement démographique du pays, ce qui a entraîné le déclin de l'importance du Japon face à une Chine en pleine ascension géopolitique. Comme le conclut le major Katsumi Terao, "lorsque la réforme constitutionnelle sera réalisée, les douleurs et les désirs de Mishima seront apaisés et il deviendra un bouddha. En attendant, son âme est dans un état d'inconsolabilité" (8).

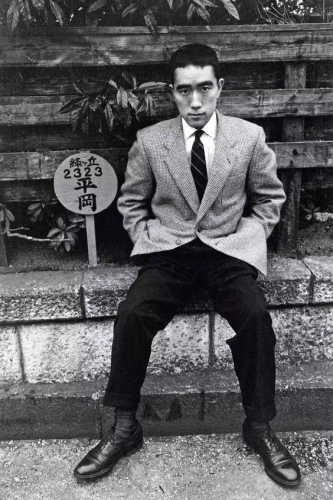

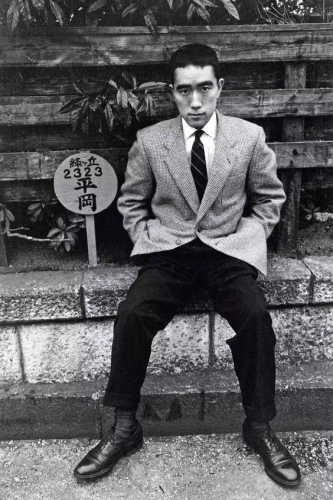

Contexte familial

Il est indéniable que le parcours de vie et la personnalité de l'écrivain ont été fortement influencés par son milieu familial. Son grand-père paternel, Sadato Hiraoka, grâce au patronage du ministre de l'Intérieur et du Premier ministre de l'époque, Takashi Hara, est devenu gouverneur de Karabuto, une province couvrant le sud de l'île de Sakhaline, que le Japon avait gagné aux dépens de la Russie après la victoire de la guerre de 1905 et qu'il a perdue au profit de l'URSS après la défaite de la guerre de 1945. Une série de mésaventures, d'opérations financières douteuses et de luttes de factions pendant la présidence de T. Hara et après son assassinat, tandis que S. Hiraoka était au poste de gouverneur, ce qui a entraîné une dégradation rapide de la position de la famille du futur écrivain.

Cette dégradation se retrouve dans le caractère bourru et apodictique de Natsuko, la grand-mère de Kimitake Hiraoka, amatrice de kabuki et de théâtre nō. Son caractère est marqué par la fierté d'être issue de la famille Tokugawa et d'avoir hérité d'une riche tradition culturelle, ainsi que par un sentiment d'impuissance, dû à la conscience des conséquences de la privation de pouvoir et de prestige de la famille après la restauration Meji. Un motif qui revient souvent dans les œuvres de Mishima. Le motif de la beauté nostalgique et de la résignation tranquille chez Mishima fait écho au souvenir de la doyenne de la famille.

Le grand-père paternel de Natsuko, Naoyuki Nagai, était un descendant de la famille féodale Mikawa-han (daimyō) et occupait une position élevée dans l'administration Tokugawa, responsable, entre autres, des négociations avec les pays occidentaux et de la construction de la marine japonaise et de la première aciérie du Japon. Son grand-père maternel, Yoritaka Matsudaira, était quant à lui le dernier daimyō de la famille Sisido-han, un prêtre important de la religion shintoïste. La famille de Natsuko, tant du côté paternel que maternel, était étroitement liée au clan Tokugawa. Grâce à l'appartenance de sa grand-mère à l'aristocratie (Kazoku), le jeune K. Hiraoka a pu entrer à Gakushuin, l'équivalent japonais du collège britannique d'Eton.

Le futur écrivain, compte tenu de la soumission et de la maladresse de son père Azusa Hiraoka, a été principalement élevé par sa grand-mère surprotectrice, ce qui s'est déroulé dans des conditions assez particulières et dans une atmosphère familiale malsaine, et a probablement été décisif pour l'émergence de motifs pathologiques dans ses déclarations sur la sexualité. Ces thèmes, ainsi que la prétendue bisexualité de K. Hiraoki, suscitent généralement une fascination malsaine chez ceux qui s'intéressent à sa personne, mais nous ne les développerons pas ici car, à notre avis, ils n'ont rien à voir avec l'héritage idéologique et politique du "dernier samouraï" et sont, de surcroît, de formidables ragots.

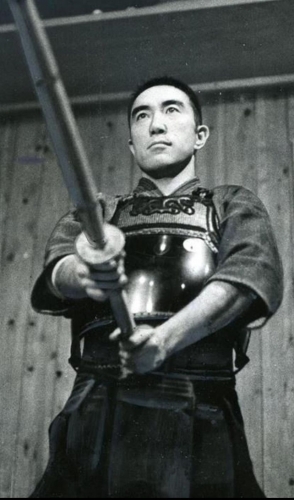

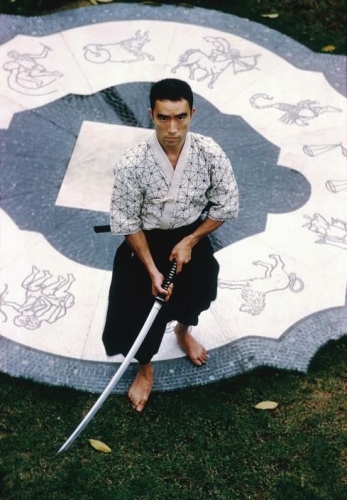

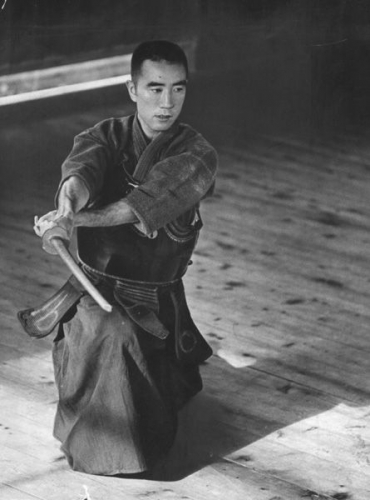

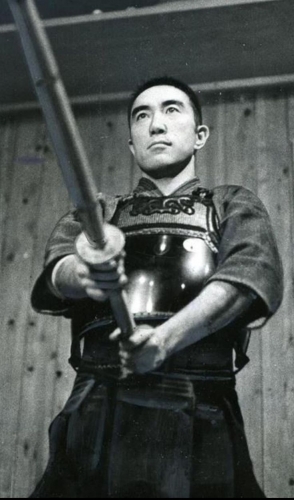

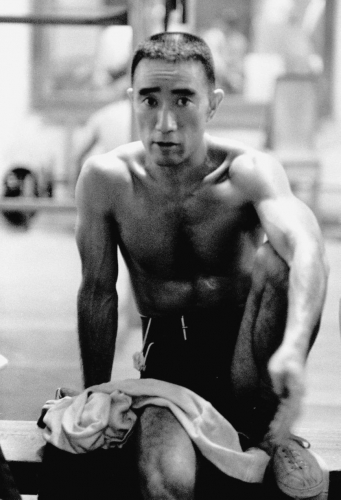

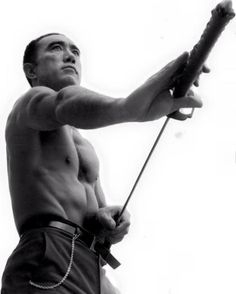

C'est également grâce aux efforts de son père, qui avait des relations dans les sphères gouvernementales, que le jeune K. Hiraoka a pu éviter le service militaire pendant la période de déclin de la guerre, à l'initiative de son père et non de lui-même. Le futur écrivain éprouvera toute sa vie des remords pour son absence au front et, au vu de la mort héroïque de nombre de ses pairs, une sorte de "traumatisme du survivant". Cela l'amènera, après la guerre, à entreprendre un programme d'exercices physiques intenses pour devenir une personne physiquement et spirituellement meilleure. C'est ainsi que Y. Mishima est entré dans l'espace culturel et spirituel du Bushidō.

Diagnostic de la crise

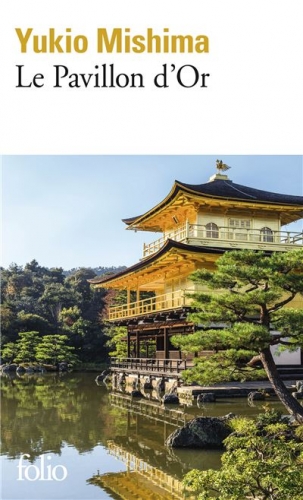

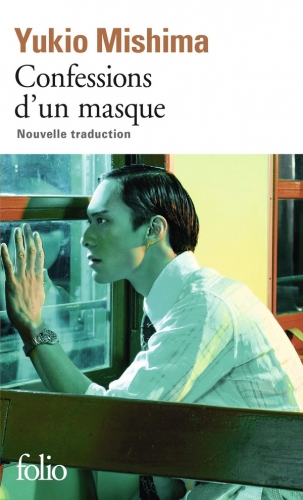

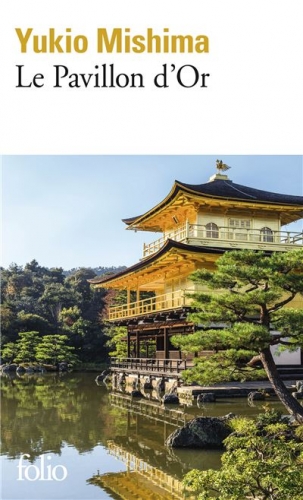

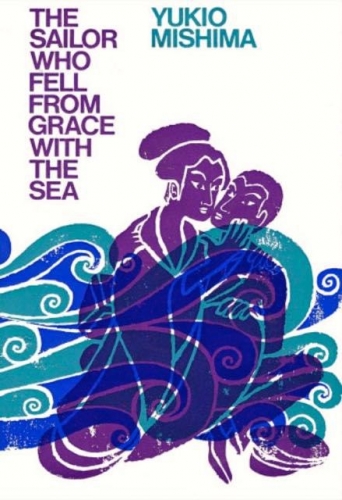

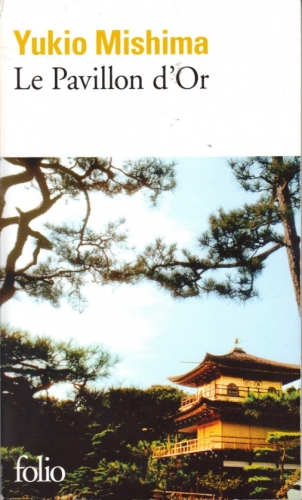

La première phase du parcours intellectuel de Y. Mishima culmine dans l'œuvre "Kinkaku-ji" ("Le Pavillon d'or", 1956) (9). Le leitmotiv des écrits de Y. Mishima au cours de cette période est une description méticuleuse de la vie intérieure des hommes japonais dans l'après-guerre (Sengo minshushugi) - une époque où la nation des guerriers, autrefois fière, s'est retrouvée plongée dans le nihilisme libéral. Il est caractéristique ici que, bien que l'art littéraire de Y. Mishima atteint son apogée dans cette œuvre de jeunesse, son identité japonaise et sa conscience nationaliste centrée sur l'idée monarchique commencent à peine à s'éveiller. Dans le Kinkaku-ji, l'étage le plus élevé, non conquis, du pavillon d'or (évoqué dans le titre du roman) peut être considéré comme une métaphore de l'idéal spirituel japonais. Y. Mishima mène à cette époque une vie de play-boy dégénéré, passant son temps dans des clubs luxueux, fréquentant des femmes tout aussi luxueuses et buvant des alcools tout aussi luxueux.

Son monde est celui d'une jeune génération d'hommes japonais dont l'âge mûr se situe dans les années d'après-guerre. Le pays est traversé par des flots d'argent étranger, les gens se sourient, cachant derrière un masque de pseudo-humanisme les conflits d'intérêts individuels qui brisent l'ensemble social organique, dans le maquis duquel il n'est plus possible de distinguer les amis des ennemis. Le mensonge et la duplicité ont détruit l'honneur et la vérité. La force physique et le travail de ses propres mains sont méprisés, tandis que la société se noie dans l'hypocrisie. Les jeunes générations étouffent dans l'apathie, la paresse, la drogue, la pornographie, la compétition dénuée de sens, mais suivent, comme un troupeau de moutons, le même chemin du matérialisme qui leur a été préparé. Les gens se dégradent en courant après l'argent. Il y a de plus en plus de voitures dont la vitesse illustre l'insensibilité de ceux qui sont derrière leur volant. De nouveaux gratte-ciel voient le jour, tandis que les principes moraux et la droiture morale sont en déclin. Les vitres brillantes des vitrines sont comme une invite à des convoitises auxquelles nous ne pouvons échapper et à travers lesquelles nous pouvons apercevoir notre vide spirituel. Lorsque les ailes des aigles kamikazes s'élançant vers le ciel se brisent, ils sont moqués et ridiculisés par les termites en costume-cravate qui rampent entre les gratte-ciel de verre (10).

Les sources de la crise

C'est face à cette époque que "l'Empereur est devenu simplement humain". Les années 1960 ont été une décennie d'activité hideuse pour des gens spirituellement vidés de leur substance autour d'une chose aussi plate que la croissance économique. Dans la nouvelle "Eirei no Koe" ("Voix des héros déchus", 1966) de Y. Mishima, par la bouche de ceux qui sont tombés lors du coup d'État nationaliste manqué du 26 février 1936, crée un double portrait de l'empereur Hirohito: d'une part, il est la personnification sacrée du mythe national japonais; d'autre part, ayant renoncé à son statut de "dieu ayant pris la forme d'un homme" (Arahitogami), il n'est plus qu'un grand-père souriant et bon enfant, présidant à la rationalité économique du capitalisme d'après-guerre, légitimant la routine quotidienne du Japon d'après-guerre.

Le règne de Shōwa est marqué par les couleurs rouge et gris cendré. Le rouge sang s'achève avec le dernier jour de la guerre, le gris cendré commence avec la déclaration de l'empereur "Je ne suis qu'un être humain". Le rouge est la sincérité suprême des esprits fraternellement unis de ceux qui ont sacrifié leur vie sur l'autel de la patrie lors de "l'incident du 26 février" (c'est ainsi que la tentative de coup d'Etat manquée de 1936 a été désignée dans le récit officiel japonais) et lors des attaques kamikazes de Tokkottai à la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale. La mort des héros tombés pour la patrie devient insignifiante et inutile face à l'abdication de la divinité par Hirohito, perdant ainsi son caractère sacré. La période "grise" de Shōwa est pour Y. Mishima inacceptable, les esprits des héros s'exprimant à travers sa plume accusent Hirohito de trahir leur patriotisme et leurs cœurs purs.

Lors de la célébration du septième anniversaire de la mort de Y. Mishima, sa mère Shizue a révélé que "Eirei no Kobe" a dû être écrit en une nuit. Lorsqu'elle a demandé à son fils comment il était parvenu à écrire une œuvre aussi subtile en si peu de temps, il a répondu: "J'ai senti ma main bouger d'elle-même et le stylo se déplacer de lui-même sur le papier. Je ne pouvais pas arrêter ma main, même si je le voulais. Des voix discrètes, comme des chuchotements, ont retenti dans ma chambre à minuit. Ces voix semblaient provenir d'un groupe d'hommes. En retenant mon souffle et en écoutant attentivement, j'ai compris qu'il s'agissait des voix des soldats tombés au combat lors de l'incident du 26 février" (11).

Révolution conservatrice

Mishima éprouvait une grande sympathie pour les jeunes officiers et soldats qui avaient déclenché la mutinerie du 26 février, partageant leur agrarisme rustique et leur aversion radicale pour la modernité, le capitalisme et la civilisation urbaine. L'auteur d'"Eirei no Kobe" ne considérait pas les participants à l'"incident du 26 février" comme des rebelles déloyaux, mais comme de nobles patriotes-guerriers, prêts à se sacrifier pour défendre la justice, la tradition et le bien commun du peuple japonais. Il a été profondément attristé, déçu et déchiré par le fait que l'empereur Shōwa ait choisi de ne pas écouter les voix sincères des auteurs de la conspiration, ordonnant au contraire qu'ils soient exécutés à l'issue d'un simulacre de procès. Y. Mishima se range du côté des soldats qui ont prêté serment d'allégeance à l'empereur, mais qui ont été lésés par lui, abandonnés et condamnés à l'oubli.

La tentative d'assassinat du 26 février 1936 est l'une des plus importantes du Japon de l'entre-deux-guerres. Ce jour-là, à 8h15, des barricades s'élèvent dans plusieurs quartiers de Tokyo et la confusion la plus totale règne. Au cours de la nuit, les conspirateurs ont réussi à assassiner l'amiral Saitō Makoto, le ministre Takashi Korekiyo, le général Jōtarō Watanabe et le beau-frère du Premier ministre Okada Keisuki. L'amiral Suzuki Kantaro est également gravement blessé. Regroupés au sein de l'organisation nationaliste Kōdō-ha (Imperial Way Faction), les assassins détruisent également l'imprimerie du journal libéral Asahi et occupent pendant trois jours le siège du ministère de la Guerre, l'état-major, le quartier général de la police de la capitale et le nouveau bâtiment du parlement, avant de déposer les armes sur ordre de l'empereur. La rébellion a impliqué environ 1400 soldats des 1er et 3e régiments d'infanterie, du 7e régiment d'artillerie lourde, de la garde impériale et des milieux civils. Le chef de la conspiration était Teruzō Andō du 3e régiment d'infanterie, et les participants civils comprenaient Kita Ikki et Nishida Zei. La conspiration a été personnellement condamnée par l'empereur, et ses participants militaires et civils ont été jugés et exécutés par des pelotons d'exécution quelques mois plus tard (12).

Le monarchisme

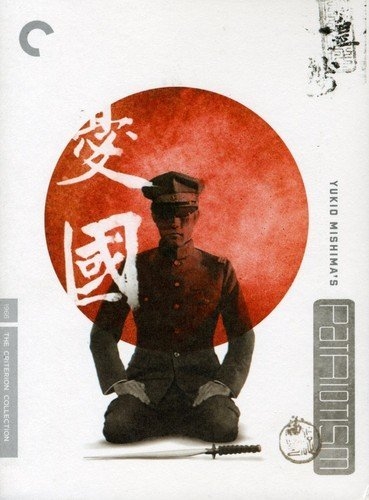

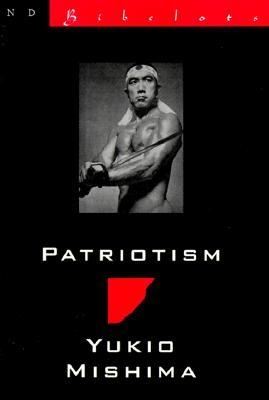

Le monarchisme de l'auteur de "Voices of the Ghosts of Fallen Heroes" se référait donc au Dentō, le système monarchique japonais unique formé au cours d'un développement historique organique, et au Kōtō, la dynastie régnante. Son sujet, en revanche, n'était pas l'individu Tennō, distinction qu'a faite Y. Mishima, qui a vivement critiqué les actions de Hirohito avant et après la guerre. Il condamnait en particulier la dissociation de Hirohito avec les dirigeants du soulèvement du 26 février 1936, le capitaine Asaichi Isobe (photo) et le capitaine principal Hisashi Kōno. C'est sur les archives pénitentiaires du premier que Y. Mishima a basé le contenu de la nouvelle "Yūkoku" ("Patriotisme", 1961) (13).

Le monarchisme de l'auteur de "Voices of the Ghosts of Fallen Heroes" se référait donc au Dentō, le système monarchique japonais unique formé au cours d'un développement historique organique, et au Kōtō, la dynastie régnante. Son sujet, en revanche, n'était pas l'individu Tennō, distinction qu'a faite Y. Mishima, qui a vivement critiqué les actions de Hirohito avant et après la guerre. Il condamnait en particulier la dissociation de Hirohito avec les dirigeants du soulèvement du 26 février 1936, le capitaine Asaichi Isobe (photo) et le capitaine principal Hisashi Kōno. C'est sur les archives pénitentiaires du premier que Y. Mishima a basé le contenu de la nouvelle "Yūkoku" ("Patriotisme", 1961) (13).

L'empereur, furieux de l'assassinat de ses ministres par de jeunes commandants militaires rebelles, refuse d'écouter leurs raisons, ne prend pas parti, ordonne la répression de la rébellion et le jugement et la condamnation des participants. Son rejet des auteurs de la révolte nationaliste et anticapitaliste du 26 février rappelle la renonciation au statut divin après la guerre, qui était de facto un geste de coopération, voire une tentative d'intégration politique avec les envahisseurs et occupants yankees. Pour Y. Mishima, le règne de Shōwa chancelle pour ainsi entre 1936 et 1945.

La formation monarchiste de l'auteur de "Yūkoku" est bien illustrée par sa conversation avec Tsukasa Kōno, le frère aîné de Hisashi Kōno, qui fut l'une des figures les plus importantes de la révolte du 26 février et se suicida après sa défaite. Y. Mishima cite dans l'interview les propos de l'empereur Hirohito, qui s'était exprimé de manière désobligeante sur les révoltes du 26 février: "Qu'ils se suicident s'ils le souhaitent. Je n'ai pas l'intention d'honorer ces illégaux en leur envoyant mon représentant". L'auteur de "Eirei no Koe" commente: "Ce n'est pas un comportement digne d'un empereur japonais. C'est très triste". Cependant, lorsque Tsukasa demande "Si ces jeunes officiers avaient su ce que l'Empereur avait dit, auraient-ils crié devant le peloton d'exécution "Tennō Heika Banzai !" ("Longue vie à Sa Majesté l'Empereur")?", Y. Mishima lui répond : "Même lorsque l'empereur ne se comporte pas comme un empereur, les sujets doivent se comporter comme des sujets. Les assassins savaient qu'ils devaient remplir leur devoir de sujets en poussant le cri "Vive l'Empereur !" et en croyant en la justice du Ciel. Mais quelle tragédie pour le Japon !" (14).

L'empereur doit unifier la société japonaise en étant une figure symbolique et en se plaçant au-dessus du domaine politique. Si la monarchie était le centre de l'unité nationale et culturelle, elle créerait un espace pour le débat politique et la créativité culturelle sans affaiblir la cohésion de la société. La monarchie doit être enracinée dans la tradition japonaise, mais aussi créer un espace pour l'intégration d'éléments importants de la modernité, y compris le pluralisme politique et la liberté culturelle. Le monarque, en tant que symbole de l'unité nationale et culturelle du peuple japonais, devait garantir la préservation et l'inviolabilité de l'essence de l'histoire et de la tradition nationales japonaises. Sur le plan politique, le monarchisme de Y. Mishima est donc très décevant, étant pratiquement incompatible avec le démolibéralisme et avec la présence du Japon dans la sphère d'influence yankee et le cercle civilisationnel de l'Occident.

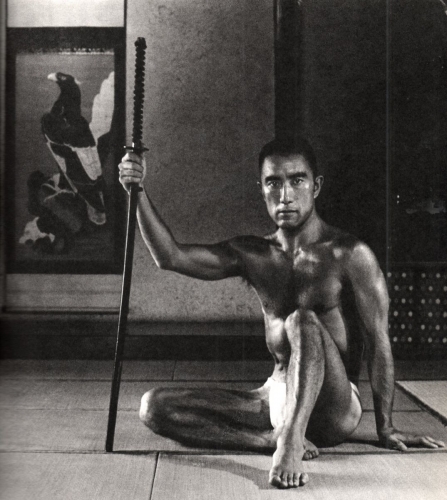

L'harmonie du sabre et de la plume

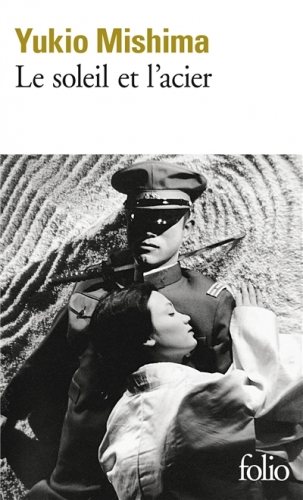

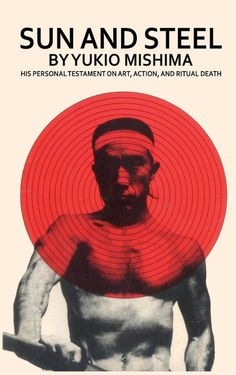

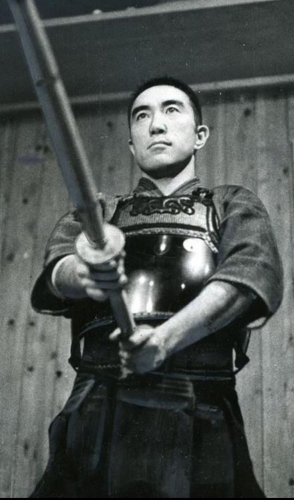

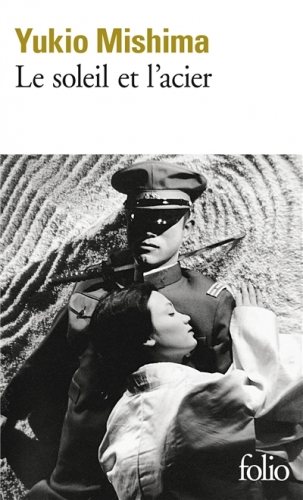

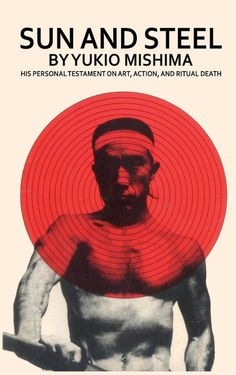

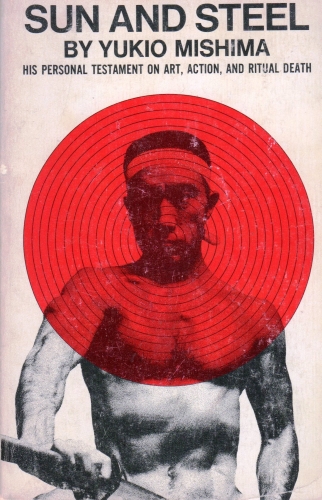

Sur le plan culturel, en revanche, sa pensée conserve une valeur d'inspiration idéologique et ses essais tels que "Pour les jeunes samouraïs", "Introduction à Hagakure" (1967), "Soleil et acier" (1965-1968) et "Défense de la culture" (1968) sont très populaires, y compris en Europe, notamment parmi les nationalistes français et italiens. Y. Mishima défend dans ces textes les traditions politiques, culturelles et militaires japonaises, y compris le code Bushidō, mais aussi l'héritage plus large des classiques japonais et chinois de la fiction, de la poésie, du théâtre, de la philosophie, etc. Comme le note le critique littéraire Koichiro Tamioka, on trouve notamment dans le recueil Le Soleil et l'acier, les idées philosophiques et historiosophiques de Y. Mishima.

Sur le plan culturel, en revanche, sa pensée conserve une valeur d'inspiration idéologique et ses essais tels que "Pour les jeunes samouraïs", "Introduction à Hagakure" (1967), "Soleil et acier" (1965-1968) et "Défense de la culture" (1968) sont très populaires, y compris en Europe, notamment parmi les nationalistes français et italiens. Y. Mishima défend dans ces textes les traditions politiques, culturelles et militaires japonaises, y compris le code Bushidō, mais aussi l'héritage plus large des classiques japonais et chinois de la fiction, de la poésie, du théâtre, de la philosophie, etc. Comme le note le critique littéraire Koichiro Tamioka, on trouve notamment dans le recueil Le Soleil et l'acier, les idées philosophiques et historiosophiques de Y. Mishima.

Dans l'après-guerre, le système de valeurs japonais s'est désintégré, avec la disparition de l'art traditionnel du sabre (Bu) et la dégradation de l'art de la plume (Bun). Le code traditionnel "Bu-Bun-Ryodo" doit donc être ravivé, car c'est dans la tension créative créée par le contraste entre "Bu" et "Bun" que la sensibilité japonaise traditionnelle peut être retrouvée. Comme l'a dit Y. Mishima lui-même, "Pratiquer les arts martiaux signifie se battre et tomber comme une fleur qui s'épanouit, pratiquer l'art de la plume signifie cultiver des fleurs qui ne cesseront jamais de s'épanouir".

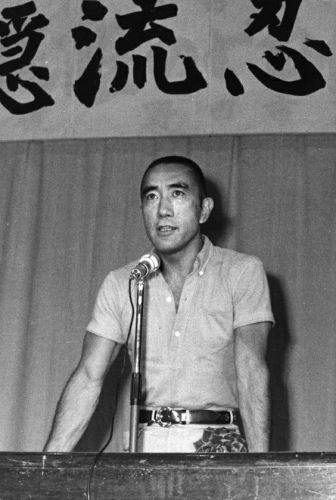

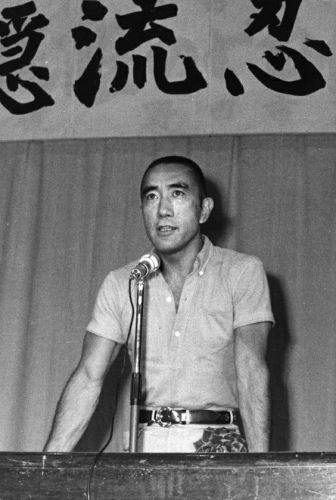

Lors d'un débat avec les étudiants communistes qui occupaient l'université de Tokyo en 1969, Y. Mishima a présenté des points de vue conservateurs, tandis que les étudiants se sont rangés du côté de l'avenir, prônant de transcender les limites du temps et proposant une révolution conceptuelle réalisée dans de nouveaux espaces conceptuels. L'auteur de "La défense de la culture" plaidait plutôt pour une vision organique du temps et de la continuité historique en relation avec des idées telles que l'empereur, la morale de la violence, la personnalité et le corps, l'art et l'esthétique, l'espace et le temps, la politique et la littérature, la beauté en tant que concept et en tant que réalité, etc. Le débat s'est déroulé à un niveau intellectuel très élevé, oscillant entre des questions politiques d'actualité et des sujets philosophiques et historiosophiques plus abstraits. Ce faisant, Mishima rejoignait ses opposants de gauche dans leur rejet du capitalisme et des grandes entreprises, déclarant: "Si vous reconnaissiez la sainteté et l'onction de l'empereur, alors je me joindrais à vous" (15).

Le traditionalisme

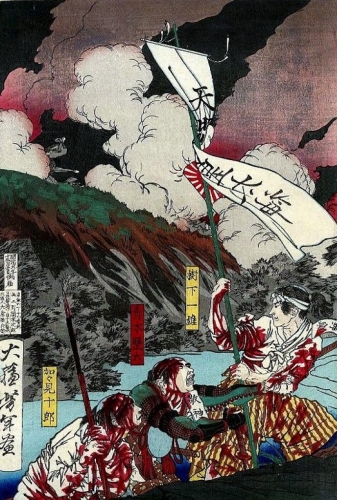

En 1966, Y. Mishima se rend dans la préfecture de Kumamoto, sur l'île de Kiusiu, où un groupe de samouraïs connu sous le nom de Shinpūren (Ligue du vent divin) s'était formé en 1876. Quelque 170 guerriers opposés à la politique modernisatrice de Meji, armés d'armes traditionnelles japonaises telles que le sabre (katana), la lance (jari) et la machette (naginata), attaquent la garnison locale. Les soldats, surpris, ont d'abord paniqué. Cependant, ils se sont rapidement regroupés et ont commencé à tirer des salves successives sur les guerriers Shinpūren qui avançaient, vêtus d'armures et armés de sabres. 123 samouraïs perdirent la vie au combat ou se firent seppuku, gravement blessés. Parmi les morts, on compte également une douzaine de jeunes âgés de 16 à 17 ans. La rébellion fut ridiculisée par la presse tokyoïte de l'époque, qui y voyait l'expression d'un anachronisme et d'un primitivisme.

La rébellion de Shinpūren s'inscrit dans une série de soulèvements similaires entre 1873 et 1877, dont le plus important fut celui du duché de Satsuma en 1877, mené par Takamori Saigō. Leur cause était l'abolition, en août 1871, de l'autonomie des domaines féodaux des daimyō qui soutenaient les samouraïs. Les salaires précédemment versés aux samouraïs par les daimyō furent réduits de moitié et convertis en obligations d'État, ce qui entraîna rapidement la ruine de nombreux chevaliers, principalement parmi les plus pauvres. La dégradation économique s'accompagne également d'une dégradation symbolique: en 1871, l'aristocratie perd le monopole de l'utilisation des noms de famille (les paysans obtiennent également le droit d'en avoir) et l'obligation pour les samouraïs de porter des sabres en public est abolie, avec une interdiction totale de leur utilisation par les non-officiers de l'armée gouvernementale en 1876. En 1871 également, les paysans ont été dispensés de se prosterner devant les samouraïs, et les paysans ont été autorisés à monter à cheval et à épouser des ressortissants d'autres castes. Cependant, le coup le plus dur porté aux samouraïs et la cause immédiate de leurs révoltes fut la création d'une armée régulière, pour laquelle les premiers enrôlements eurent lieu en 1873 (16).

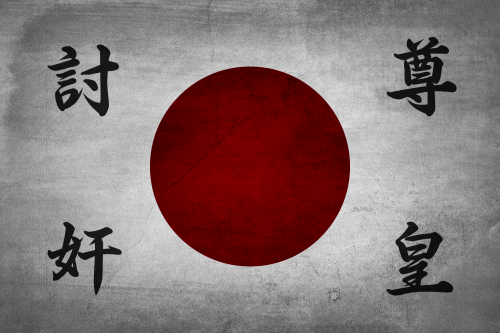

Les raisons de la fascination de Y. Mishima pour la rébellion des Shinpūren nous permettent de mieux comprendre ses vues historiosophiques et civilisationnelles. Les Shinpūren se sont opposés à la restauration Meji, commencée en 1868, dont l'idée originale était de "restaurer la dignité de l'empereur et d'expulser les barbares d'outre-mer" (Sonnojoi). Le pouvoir devait appartenir à l'empereur, et non plus aux shoguns Tokugawa, et les "navires noirs" yankees, détestés, devaient être définitivement chassés du pays. Après le renversement du shogunat Tokugawa, le régime de Meiji a toutefois commencé à mettre en œuvre une politique d'occidentalisation drastique dans le Japon du XIXe siècle, que l'on peut comparer aux actions analogues du tsar Pierre Ier dans la Russie du XVIIIe siècle et du shah Reza Pahlavi dans l'Iran du XXe siècle.

Le Japon s'est ouvert aux influences occidentales et a commencé à imiter les recettes civilisationnelles occidentales, tout en limitant et en éliminant les coutumes traditionnelles de la société japonaise, stigmatisées par le nouveau régime comme non civilisées et non occidentales. L'aristocratie des samouraïs (Shizoku), surclassée, a été contrainte de couper ses chignons traditionnellement portés à l'arrière de la tête et ses membres se sont vu interdire de porter des épées en public - ce qui, à leurs yeux, avait une signification sacrée et constituait un droit inaliénable, distinguant les chevaliers des autres états sociaux.

Le rejet de la restauration Meiji par les Shinpūren était extrême et s'exprimait par des actions de nature strictement primitiviste. Les Shinpūren n'acceptaient pas le papier-monnaie, et lorsque celui-ci fut mis en circulation à la place des pièces de monnaie, ils refusaient de le toucher avec leurs mains et ne le ramassaient qu'à l'aide de bâtons de riz. Lorsqu'ils rencontraient quelqu'un habillé à l'occidentale, ils jetaient du sel sur le sol à l'endroit où il se tenait. Ils refusaient d'utiliser les "armes sales des barbares occidentaux", ne reconnaissant que les armes traditionnelles japonaises. Ils contournaient les lignes à haute tension à distance et, lorsque cela n'était pas possible, ils se couvraient la tête de feuilles de papier et couraient rapidement sous les fils. Leur rejet de la civilisation occidentale moderne était total, leur xénophobie identitaire et leur traditionalisme intégraux.

Pour comprendre Y. Mishima, donnons-lui la parole: "Quand on parle de fidélité à sa propre pensée, on parle d'une pensée exprimée par l'action, en marge de laquelle apparaissent cependant des impuretés, des tactiques, des crispations humaines. Il en est ainsi des idéologies, où la fin semble toujours justifier les moyens. Les Shinpūren, cependant, étaient une exception au mode où la fin justifie les moyens, la fin équilibrait les moyens dans leur cas et les moyens équilibraient les fins, l'un et l'autre se conformant à la direction indiquée par les dieux, étant libres de la contradiction et de la déviation de la fin par rapport aux moyens, présentes dans tous les autres mouvements politiques. C'est l'équivalent du rapport entre le contenu et le style d'expression dans l'art. Je suis convaincu que c'est aussi en cela que réside l'essence de l'esprit japonais, dans le sens de son action la plus pure (Yamatodamashii)" (17).

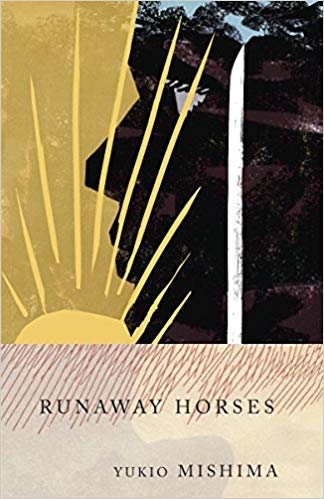

Un écho de l'épopée de Shinpūren peut également être entendu dans l'œuvre littéraire la plus aboutie de Y. Mishima. La tétralogie de Mishima 'Hōjō no Umi' ('Mer de fertilité', 1965-1971) l'atteste, plus précisément dans son deuxième tome 'Honba' ('Chevaux au galop', 1967-1968). L'un des protagonistes de l'histoire, Isao Liniuma, s'inspire de l'œuvre "Histoire des Shinpūren", souhaitant créer les "Shinpūren de l'ère Shōwa". La pièce, lue par Isao, 19 ans, a été placée dans son intégralité dans la nouvelle "Galloping Horses", ce qui lui confère le caractère d'une histoire funèbre. Située dans les années 1930, l'intrigue de "Galloping Horses" suit un groupe de jeunes conspirateurs militaires qui planifient l'assassinat d'un financier et bureaucrate du gouvernement nommé Kurahara. Ce dernier incarne à son tour les tendances technocratiques et mécanistes du régime Shōwa, qui considère la "stabilité de la monnaie" comme le facteur déterminant le bonheur de la société. "L'économie n'est pas de la philanthropie ; soit vous acceptez des pertes représentant 10% de la société pour sauver les 90% restants, soit les 100% restants devront mourir", déclare Kurahara.

Il s'agit d'une attitude radicalement opposée à l'idéal patriarcal d'avant-guerre de l'empereur en tant que "bon dirigeant", prenant soin de son peuple, défendant l'identité, l'histoire et le destin du peuple japonais. Y. Mishima lui-même adhérait à cet idéal traditionnel de l'empereur. C'est cette vision de l'empereur qu'il prêchait, qu'il vénérait, et pour laquelle les protagonistes de ses œuvres se sont sacrifiés. Pour défendre l'Empereur ainsi compris, le "dernier samouraï" a également sacrifié sa propre vie, en commettant le seppuku le 25 novembre 1970, après l'échec du coup d'État, qui était guidé par l'idée de retrouver pour l'Empereur le statut divin, et pour les Jieitai (Forces d'autodéfense) le statut de forces armées légitimes de l'État. Par son action, Y. Mishima a prouvé l'unité de la pensée et de l'action, l'unité de l'épée et de la plume, ressuscitant l'idéal traditionnel de la civilisation japonaise, dont il est devenu l'incarnation et le symbole pour les générations suivantes de patriotes japonais.

Il s'agit d'une attitude radicalement opposée à l'idéal patriarcal d'avant-guerre de l'empereur en tant que "bon dirigeant", prenant soin de son peuple, défendant l'identité, l'histoire et le destin du peuple japonais. Y. Mishima lui-même adhérait à cet idéal traditionnel de l'empereur. C'est cette vision de l'empereur qu'il prêchait, qu'il vénérait, et pour laquelle les protagonistes de ses œuvres se sont sacrifiés. Pour défendre l'Empereur ainsi compris, le "dernier samouraï" a également sacrifié sa propre vie, en commettant le seppuku le 25 novembre 1970, après l'échec du coup d'État, qui était guidé par l'idée de retrouver pour l'Empereur le statut divin, et pour les Jieitai (Forces d'autodéfense) le statut de forces armées légitimes de l'État. Par son action, Y. Mishima a prouvé l'unité de la pensée et de l'action, l'unité de l'épée et de la plume, ressuscitant l'idéal traditionnel de la civilisation japonaise, dont il est devenu l'incarnation et le symbole pour les générations suivantes de patriotes japonais.

L'héritage

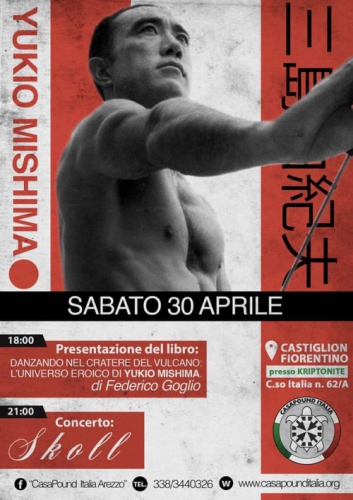

La mémoire du "dernier samouraï" est célébrée lors des anniversaires de la mort des patriotes (Yukokuki), qui ont lieu chaque année depuis 1971 et rassemblent des centaines de nationalistes de toutes les régions du Japon et de toutes les tranches d'âge, ainsi que des militaires, à la date du discours de Y. Mishima prononcé lors de la cérémonie de remise des prix. Mishima depuis le balcon de la garnison Jieitai de Tokyo a eu un effet formateur - même si, ayant été témoins directs, les soldats l'ont d'abord reçu avec dérision. Jusqu'à présent, le Yukokuki a également été organisé deux fois en Europe - par l'écrivain japonais nationaliste Tadao Takemoto à Paris et par l'universitaire italien conservateur Romano Vulpitta à Rome. L'officier le plus célèbre, formé par l'idée de Y. Misima est le major Katsumi Terao, qui faisait partie du groupe d'officiers militaires qui s'est introduit dans la salle contrôlée par Y. Mishima en 1970 pour tenter de sauver le général K. Mashita, qui avait été séquestré par ce dernier et ses partisans. K. Terao est alors blessé à deux reprises par Y. Mishima. Mishima, deux fois blessé d'un coup d'épée dans le dos et une fois coupé à l'épaule. Même après la mort de l'écrivain, il s'est rallié à lui sur le plan politique et a consacré les années suivantes de sa vie à promouvoir ses idées et à œuvrer en faveur d'une réforme constitutionnelle qui légaliserait l'existence de l'armée japonaise.

En 2015, un certain nombre de livres consacrés à Y. Mishima, rédigés par d'anciens membres du Tate no kai ou des officiers du Jieitai : "The Young Officers Who Last Met Yukio Mishima" (2019) par Shigeki Nishimura ; "Army of Shadows ; The Truth About Mishima's Death" (2001) par Kyokatsu Jamamoto ; "Yukio Mishima and the Japanese Self-Defence Forces" (1997) par Yusuke Sugihara ; "Traces of Fire : Confessions des 30 anciens membres du Tatenokai" (2005) par Aemi Suzuki et Tsukasa Tamura ; "Réforme constitutionnelle dédiée à l'empereur" (2013) par Kjoshi Honda ; "Promesse non tenue" (2006) par Toyoo Inoue ; "Après Yukio Mishima" (1999) par Masahiro Mijazaki ; "C'est ce que Yukio Misima a dit" (2017) par Jutaki Sinohara ; "L'époque à laquelle Yukio Misima a vécu" (2015) par Haruki Murata.

La mémoire du nationaliste japonais mérite d'être entretenue en Pologne également, et ses idées et ses réalisations devraient être rapprochées des identitaires polonais.

Ronald Lasecki

Littérature utilisée :

Benedict R., Chrysanthème et épée. Patterns of Japanese culture, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, Varsovie 2003.

Gordon A., Nowożytna historia Japonii, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, Varsovie 2010.

Hall J. W., Japan. From the earliest times to today, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, Varsovie 1979.

Flanagan. D., Mishima, Reaktion Books Ltd. 2014.

Inose N., Persona : A Biography of Yukio Mishima, Bungei Shunshu Press, Tokyo 1995.

Mishima Y, Flamme froide, trad. H. Lipszyc, Świat Książki, Varsovie 2008.

Mishima Y., La pagode d'or, trad. A. Zielińska-Elliott, Wilga, Varsovie 1997.

La politique. Un auxiliaire de l'histoire. Histoire du Japon', n° 4/2019.

Rei R., In Defence of Yukio Mishima, https://counter-currents.com/2020/01/in-defense-of-mishima/ (03.10.2020).

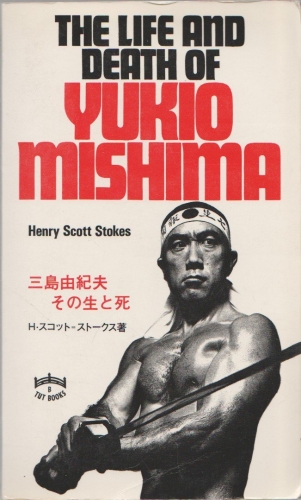

Stokes H. S., The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima, Cooper Square Press 2000.

Śpiewakowski A., Samuraje, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, Varsovie 1989.

Tubulewicz J., Histoire du Japon, Zakład Narodowy Imienia Ossolińskich-Wydawnictwo, Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków-Gdańsk-Łódź 1984.

Vulpitta R., Yukio Mishima, Yojuro Yasuda, & Fascism, part 1. https://counter-currents.com/2013/01/yukio-mishima-yojuro-yasuda-and-fascism-part-1/ (02.10.2020), part 2. https://counter-currents.com/2013/01/yukio-mishima-yojuro-yasuda-and-fascism-part-2/ (02.10.2020).

Notes:

1) R. Vulpitta, Yukio Mishima, Yojuro Yasuda, & Fascism, part 1. https://counter-currents.com/2013/01/yukio-mishima-yojuro-yasuda-and-fascism-part-1/ (02.10.2020), part 2. https://counter-currents.com/2013/01/yukio-mishima-yojuro-yasuda-and-fascism-part-2/ (02.10.2020).

2) A. Śpiewakowski, Samouraï, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, Varsovie 1989, p. 110.

3) Constitution du Japon du 3 novembre 1946 (traduite par le professeur Teruji Suzuki), https://www.pl.emb-japan.go.jp/relations/konstytucja.htm (02.10.2020).

4) K. Starecka, Occupation et démocratie, "Politique. Aide historique. Histoire du Japon', no. 4/2019, pp. 98-101.

5) Idem, Le fardeau du neuvième article, 'Politique. Une aide historique. Histoire du Japon ", n° 4/2019, p. 104.

6) M. Socha, La démission du Premier ministre Abe Shinzō : un résumé, http://osa.uni.lodz.pl/?p=11076 (02.10.2020).

7) Idem, Annonce de changements dans la stratégie de défense du Japon, http://osa.uni.lodz.pl/?p=11112 (02.10.2020).

8) R. Rei, In Defence of Mishima, commentaire sous 31 janvier 2020, https://counter-currents.com/2020/01/in-defense-of-mishima/ (02.10.2020).

9) Édition polonaise : Y. Mishima, Zlota pagoda , trad. A. Zielińska-Eliott, Wilga, Varsovie 1997.

10) Cf. N. Inose, Persona : A Biography of Yukio Mishima, Bungei Shunshu Press, Tokyo 1995, p. 323.

11) Ibid. p. 324.

12) J. Tubulewicz, Histoire du Japon, Zakład Narodowy Imienia Ossolińskich-Wydawnictwo, Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków-Gdańsk-Łódź 1984, p. 413 ; J. W. Hall, Japon. Od czasów najdawniejszych do dziś, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, Varsovie 1979, pp. 278-279 ; A. Gordon, Nowożytna historia Japonii, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, Varsovie 2010, pp. 273-274.

13) L'adaptation cinématographique de l'histoire est un court métrage, également réalisé par Y. Mishima, un film de 28 minutes portant le même titre (il fonctionne également sous le titre anglais "Patriotism or the Rite of Love and Death") datant de 1966.

14) R. Rei, In Defence of Mishima, https://counter-currents.com/2020/01/in-defense-of-mishima/#_ftn1 (01.10.2020).

15) Cite pour : ibid.

16) J. Tubulewicz, Ibid. pp. 350-351 ; J. W. Hall, Ibid. pp. 232-235 ; A. Gordon, Ibid. pp. 100-103 ; A. Śpiewakowski, Ibid. pp. 100-101, 138.

17) Cité pour : N. Inose, Ibid, pp. 327,328.

Publié à l'origine dans Templum Novum, 2020.

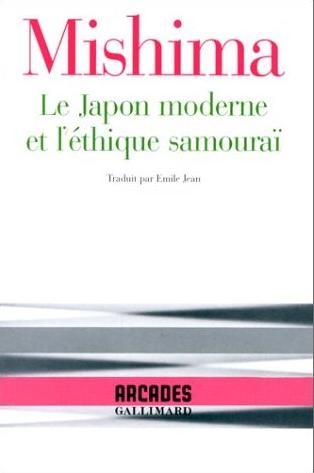

Par-delà le rôle moteur de l’armée, Mishima Yukio défend le rétablissement de la pleine souveraineté de Tokyo. Or, il sait que son pays sorti des ruines de l’après-guerre est une colonie de l’Occident anglo-saxon. « Le soi-disant contrôle par le pouvoir civil des militaires anglais et américains est uniquement un contrôle financier (p. 25). » Il dénonce que l’île méridionale d’Okinawa soit encore sous la tutelle de Washington. Il ignore que les États-Unis la rétrocéderont au Japon en 1972. Il s’offusque que le Japon signe le traité de non-prolifération nucléaire et renonce ainsi à la détention d’une force de frappe atomique. Clairvoyant, il prévient que la soumission du Jieitai aux vainqueurs de 1945 en fera, « comme les gauchistes l’ont remarqué, une force mercenaire de l’Amérique pour toujours (p. 27) ».

Par-delà le rôle moteur de l’armée, Mishima Yukio défend le rétablissement de la pleine souveraineté de Tokyo. Or, il sait que son pays sorti des ruines de l’après-guerre est une colonie de l’Occident anglo-saxon. « Le soi-disant contrôle par le pouvoir civil des militaires anglais et américains est uniquement un contrôle financier (p. 25). » Il dénonce que l’île méridionale d’Okinawa soit encore sous la tutelle de Washington. Il ignore que les États-Unis la rétrocéderont au Japon en 1972. Il s’offusque que le Japon signe le traité de non-prolifération nucléaire et renonce ainsi à la détention d’une force de frappe atomique. Clairvoyant, il prévient que la soumission du Jieitai aux vainqueurs de 1945 en fera, « comme les gauchistes l’ont remarqué, une force mercenaire de l’Amérique pour toujours (p. 27) ».

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Le monarchisme de l'auteur de "Voices of the Ghosts of Fallen Heroes" se référait donc au Dentō, le système monarchique japonais unique formé au cours d'un développement historique organique, et au Kōtō, la dynastie régnante. Son sujet, en revanche, n'était pas l'individu Tennō, distinction qu'a faite Y. Mishima, qui a vivement critiqué les actions de Hirohito avant et après la guerre. Il condamnait en particulier la dissociation de Hirohito avec les dirigeants du soulèvement du 26 février 1936, le capitaine Asaichi Isobe (photo) et le capitaine principal Hisashi Kōno. C'est sur les archives pénitentiaires du premier que Y. Mishima a basé le contenu de la nouvelle "Yūkoku" ("Patriotisme", 1961) (13).

Le monarchisme de l'auteur de "Voices of the Ghosts of Fallen Heroes" se référait donc au Dentō, le système monarchique japonais unique formé au cours d'un développement historique organique, et au Kōtō, la dynastie régnante. Son sujet, en revanche, n'était pas l'individu Tennō, distinction qu'a faite Y. Mishima, qui a vivement critiqué les actions de Hirohito avant et après la guerre. Il condamnait en particulier la dissociation de Hirohito avec les dirigeants du soulèvement du 26 février 1936, le capitaine Asaichi Isobe (photo) et le capitaine principal Hisashi Kōno. C'est sur les archives pénitentiaires du premier que Y. Mishima a basé le contenu de la nouvelle "Yūkoku" ("Patriotisme", 1961) (13).

Sur le plan culturel, en revanche, sa pensée conserve une valeur d'inspiration idéologique et ses essais tels que "Pour les jeunes samouraïs", "Introduction à Hagakure" (1967), "Soleil et acier" (1965-1968) et "Défense de la culture" (1968) sont très populaires, y compris en Europe, notamment parmi les nationalistes français et italiens. Y. Mishima défend dans ces textes les traditions politiques, culturelles et militaires japonaises, y compris le code Bushidō, mais aussi l'héritage plus large des classiques japonais et chinois de la fiction, de la poésie, du théâtre, de la philosophie, etc. Comme le note le critique littéraire Koichiro Tamioka, on trouve notamment dans le recueil Le Soleil et l'acier, les idées philosophiques et historiosophiques de Y. Mishima.

Sur le plan culturel, en revanche, sa pensée conserve une valeur d'inspiration idéologique et ses essais tels que "Pour les jeunes samouraïs", "Introduction à Hagakure" (1967), "Soleil et acier" (1965-1968) et "Défense de la culture" (1968) sont très populaires, y compris en Europe, notamment parmi les nationalistes français et italiens. Y. Mishima défend dans ces textes les traditions politiques, culturelles et militaires japonaises, y compris le code Bushidō, mais aussi l'héritage plus large des classiques japonais et chinois de la fiction, de la poésie, du théâtre, de la philosophie, etc. Comme le note le critique littéraire Koichiro Tamioka, on trouve notamment dans le recueil Le Soleil et l'acier, les idées philosophiques et historiosophiques de Y. Mishima.

Il s'agit d'une attitude radicalement opposée à l'idéal patriarcal d'avant-guerre de l'empereur en tant que "bon dirigeant", prenant soin de son peuple, défendant l'identité, l'histoire et le destin du peuple japonais. Y. Mishima lui-même adhérait à cet idéal traditionnel de l'empereur. C'est cette vision de l'empereur qu'il prêchait, qu'il vénérait, et pour laquelle les protagonistes de ses œuvres se sont sacrifiés. Pour défendre l'Empereur ainsi compris, le "dernier samouraï" a également sacrifié sa propre vie, en commettant le seppuku le 25 novembre 1970, après l'échec du coup d'État, qui était guidé par l'idée de retrouver pour l'Empereur le statut divin, et pour les Jieitai (Forces d'autodéfense) le statut de forces armées légitimes de l'État. Par son action, Y. Mishima a prouvé l'unité de la pensée et de l'action, l'unité de l'épée et de la plume, ressuscitant l'idéal traditionnel de la civilisation japonaise, dont il est devenu l'incarnation et le symbole pour les générations suivantes de patriotes japonais.

Il s'agit d'une attitude radicalement opposée à l'idéal patriarcal d'avant-guerre de l'empereur en tant que "bon dirigeant", prenant soin de son peuple, défendant l'identité, l'histoire et le destin du peuple japonais. Y. Mishima lui-même adhérait à cet idéal traditionnel de l'empereur. C'est cette vision de l'empereur qu'il prêchait, qu'il vénérait, et pour laquelle les protagonistes de ses œuvres se sont sacrifiés. Pour défendre l'Empereur ainsi compris, le "dernier samouraï" a également sacrifié sa propre vie, en commettant le seppuku le 25 novembre 1970, après l'échec du coup d'État, qui était guidé par l'idée de retrouver pour l'Empereur le statut divin, et pour les Jieitai (Forces d'autodéfense) le statut de forces armées légitimes de l'État. Par son action, Y. Mishima a prouvé l'unité de la pensée et de l'action, l'unité de l'épée et de la plume, ressuscitant l'idéal traditionnel de la civilisation japonaise, dont il est devenu l'incarnation et le symbole pour les générations suivantes de patriotes japonais.

L'anguille de la littérature mondiale. Oui, Mishima est une anguille. Vous pensez l'avoir attrapé et puis, rien !, il s'éclipse et vous vous retrouvez les mains vides. C'est ce qui se passe si vous voulez clouer son travail à une définition qui le réduit à une boîte de conserve avec une étiquette. Mais ce que son art a pu produire en l'espace de vingt-cinq ans ne peut se résumer à quelques formules commodes. L'énigme de Mishima continue. Ceci est confirmé par un roman inédit en Italie qui est sorti dans nos librairies le 31 mars.

L'anguille de la littérature mondiale. Oui, Mishima est une anguille. Vous pensez l'avoir attrapé et puis, rien !, il s'éclipse et vous vous retrouvez les mains vides. C'est ce qui se passe si vous voulez clouer son travail à une définition qui le réduit à une boîte de conserve avec une étiquette. Mais ce que son art a pu produire en l'espace de vingt-cinq ans ne peut se résumer à quelques formules commodes. L'énigme de Mishima continue. Ceci est confirmé par un roman inédit en Italie qui est sorti dans nos librairies le 31 mars.

"Mishima, pour reprendre la précieuse définition qu'en donne Marguerite Yourcenar dans son excellent Mishima ou la Vision du vide (1980), est un "univers" dans lequel, en fait, le côté esthétique - je l'explique dans mon livre - joue un rôle prépondérant. À cet élément, le grand intellectuel et écrivain japonais a ajouté la discipline martiale/militaire, sous le signe de la redécouverte d'un héritage capital de cette culture japonaise traditionnelle à laquelle il s'est référé, dans la " deuxième partie " de sa vie, avec vigueur et rigueur ; à savoir le Bunbu Ryōdō (文武両道, la Voie de la vertu littéraire et guerrière), où la plume devient métaphoriquement une épée.

"Mishima, pour reprendre la précieuse définition qu'en donne Marguerite Yourcenar dans son excellent Mishima ou la Vision du vide (1980), est un "univers" dans lequel, en fait, le côté esthétique - je l'explique dans mon livre - joue un rôle prépondérant. À cet élément, le grand intellectuel et écrivain japonais a ajouté la discipline martiale/militaire, sous le signe de la redécouverte d'un héritage capital de cette culture japonaise traditionnelle à laquelle il s'est référé, dans la " deuxième partie " de sa vie, avec vigueur et rigueur ; à savoir le Bunbu Ryōdō (文武両道, la Voie de la vertu littéraire et guerrière), où la plume devient métaphoriquement une épée.

" Disons d'abord que Mishima était un admirateur du Vate, au point de traduire en 1965 l'une de ses œuvres : Le martyre de Saint Sébastien (1911). Outre la similitude immédiate de leurs personnalités, qui partagent une exaltation bien connue de l'action virile et de l'audace, il est utile de souligner qu'il existait également une proximité artistique entre les deux. Tous deux, bien qu'appartenant à des époques et des contextes culturels différents, relèvent de ce que les critiques littéraires appellent le "décadentisme". C'est-à-dire une déclinaison du romantisme où l'esthétique se greffe sur un "personnalisme" presque exagéré et, parfois, enclin à la désillusion, où apparaissent également des relents de dandysme.

" Disons d'abord que Mishima était un admirateur du Vate, au point de traduire en 1965 l'une de ses œuvres : Le martyre de Saint Sébastien (1911). Outre la similitude immédiate de leurs personnalités, qui partagent une exaltation bien connue de l'action virile et de l'audace, il est utile de souligner qu'il existait également une proximité artistique entre les deux. Tous deux, bien qu'appartenant à des époques et des contextes culturels différents, relèvent de ce que les critiques littéraires appellent le "décadentisme". C'est-à-dire une déclinaison du romantisme où l'esthétique se greffe sur un "personnalisme" presque exagéré et, parfois, enclin à la désillusion, où apparaissent également des relents de dandysme.

Mishima, dans la lignée de la tradition japonaise, a conçu l'existence comme un équilibre entre des hypothèses opposées, la liberté et la répression, la vie et la mort. La vie est mieux contemplée dans l'ombre de la mort ; sous la teinte mortelle, le vital est lumineux, rayonnant. Embrasser l'existence implique d'embrasser à la fois la vie et la mort, et de cette fusion découlera la vitalité. La vie doit nécessairement être équilibrée avec la mort, sinon la vie sera informe, grotesque, désordonnée.

Mishima, dans la lignée de la tradition japonaise, a conçu l'existence comme un équilibre entre des hypothèses opposées, la liberté et la répression, la vie et la mort. La vie est mieux contemplée dans l'ombre de la mort ; sous la teinte mortelle, le vital est lumineux, rayonnant. Embrasser l'existence implique d'embrasser à la fois la vie et la mort, et de cette fusion découlera la vitalité. La vie doit nécessairement être équilibrée avec la mort, sinon la vie sera informe, grotesque, désordonnée.

Assumant une « étiquette » de « réactionnaire », Yukio Mishima fonde en 1968 la Société du Bouclier. Dès février 1969, la nouvelle structure qui s’entraîne avec les unités militaires japonaises, dispose d’un « manifeste contre-révolutionnaire », le Hankakumei Sengen. Sa raison d’être ? Protéger l’Empereur (le tenno), le Japon et la culture d’un péril subversif communiste immédiat. Par-delà la disparition de l’article 9, il conteste le renoncement à l’été 1945 par le tenno lui-même de son caractère divin. Il critique la constitution libérale parlementaire d’émanation étatsunienne. Il n’accepte pas que la nation japonaise devienne un pays de second rang. Yukio Mishima s’inscrit ainsi dans des précédents héroïques comme le soulèvement de la Porte Sakurada en 1860 quand des samouraï scandalisés par les accords signés avec les « Barbares » étrangers éliminent un haut-dignitaire du gouvernement shogunal, la révolte de la Ligue du Vent Divin (Shimpûren) de 1876 ou, plus récemment, le putsch du 26 février 1936. Ce jour-là, la faction de la voie impériale (Kodoha), un courant politico-mystique au sein de l’armée impériale influencé par les écrits d’Ikki Kita (1883 – 1937), assassine les ministres des Finances et de la Justice ainsi que l’inspecteur général de l’Éducation militaire. Si la garnison de Tokyo et une partie de l’état-major se sentent proches des thèses développées par le Kodoha, la marine impériale, plus proche des rivaux de la Faction de contrôle (ou Toseiha), fait pression sur la rébellion. Les troupes loyalistes rétablissent finalement la légalité. Yukio Mishima tire de ces journées tragiques son récit Patriotisme.

Assumant une « étiquette » de « réactionnaire », Yukio Mishima fonde en 1968 la Société du Bouclier. Dès février 1969, la nouvelle structure qui s’entraîne avec les unités militaires japonaises, dispose d’un « manifeste contre-révolutionnaire », le Hankakumei Sengen. Sa raison d’être ? Protéger l’Empereur (le tenno), le Japon et la culture d’un péril subversif communiste immédiat. Par-delà la disparition de l’article 9, il conteste le renoncement à l’été 1945 par le tenno lui-même de son caractère divin. Il critique la constitution libérale parlementaire d’émanation étatsunienne. Il n’accepte pas que la nation japonaise devienne un pays de second rang. Yukio Mishima s’inscrit ainsi dans des précédents héroïques comme le soulèvement de la Porte Sakurada en 1860 quand des samouraï scandalisés par les accords signés avec les « Barbares » étrangers éliminent un haut-dignitaire du gouvernement shogunal, la révolte de la Ligue du Vent Divin (Shimpûren) de 1876 ou, plus récemment, le putsch du 26 février 1936. Ce jour-là, la faction de la voie impériale (Kodoha), un courant politico-mystique au sein de l’armée impériale influencé par les écrits d’Ikki Kita (1883 – 1937), assassine les ministres des Finances et de la Justice ainsi que l’inspecteur général de l’Éducation militaire. Si la garnison de Tokyo et une partie de l’état-major se sentent proches des thèses développées par le Kodoha, la marine impériale, plus proche des rivaux de la Faction de contrôle (ou Toseiha), fait pression sur la rébellion. Les troupes loyalistes rétablissent finalement la légalité. Yukio Mishima tire de ces journées tragiques son récit Patriotisme.

Dr. Joyce maintained that “Mishima, of course, never explored the Emperor’s role in World War II in any depth, and his chief fixation appears solely to have been the decision of the Emperor to accede to Allied demands and ‘become human.’” This is a baffling statement which again simply betrays Dr. Joyce’s lack of knowledge. Besides rightfully decrying the Showa Emperor’s self-demotion to “become human” from his traditional status of “Arahitogami” (god in human form or demigod), Mishima also critically examined the Emperor’s role in politics before, during, and after the war, which revealed that what Mishima essentially venerated was not the individual Tennō but the Kōtō (the unique and time-honored Japanese monarchical system).

Dr. Joyce maintained that “Mishima, of course, never explored the Emperor’s role in World War II in any depth, and his chief fixation appears solely to have been the decision of the Emperor to accede to Allied demands and ‘become human.’” This is a baffling statement which again simply betrays Dr. Joyce’s lack of knowledge. Besides rightfully decrying the Showa Emperor’s self-demotion to “become human” from his traditional status of “Arahitogami” (god in human form or demigod), Mishima also critically examined the Emperor’s role in politics before, during, and after the war, which revealed that what Mishima essentially venerated was not the individual Tennō but the Kōtō (the unique and time-honored Japanese monarchical system).

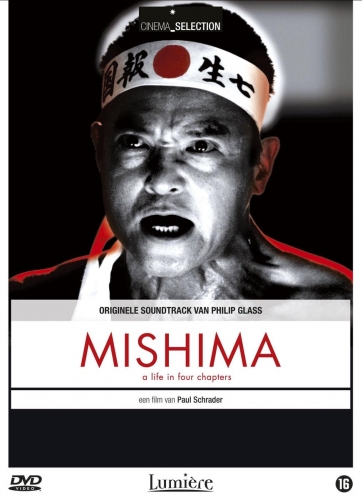

All this having been said, I still encourage people to watch Paul Schrader’s film on Mishima and to read Mishima’s guide to Hagakure (or better yet, Hagakure itself). I will myself, when time permits, try to read Mishima’s later more political fiction (e.g. Runaway Horses) and other nonfiction. A work of art is no less compelling, a logical argument no less persuasive, whatever the author’s personal deficiencies or proclivities.

All this having been said, I still encourage people to watch Paul Schrader’s film on Mishima and to read Mishima’s guide to Hagakure (or better yet, Hagakure itself). I will myself, when time permits, try to read Mishima’s later more political fiction (e.g. Runaway Horses) and other nonfiction. A work of art is no less compelling, a logical argument no less persuasive, whatever the author’s personal deficiencies or proclivities.

27-year-old Hanio Yamada, the protagonist, is a Tokyo-based copywriter who makes a decent living and leads a normal life. But his work leaves him unfulfilled. He later remarks that his job was “a kind of death: a daily grind in an over-lit, ridiculously modern office where everyone wore the latest suits and never got their hands dirty with proper work” (p. 67). One day, while reading the newspaper on the subway, he suddenly is struck by an overwhelming desire to die. That evening, he overdoses on sedatives.

27-year-old Hanio Yamada, the protagonist, is a Tokyo-based copywriter who makes a decent living and leads a normal life. But his work leaves him unfulfilled. He later remarks that his job was “a kind of death: a daily grind in an over-lit, ridiculously modern office where everyone wore the latest suits and never got their hands dirty with proper work” (p. 67). One day, while reading the newspaper on the subway, he suddenly is struck by an overwhelming desire to die. That evening, he overdoses on sedatives.

Le terme « bushidô », utilisé en ce sens serait apparue pour la première fois dans le koyo gunkan, la chronique militaire de la province du Kai dirigée par le célèbre clan des Takeda (la chronique a été compilée par Kagenori Obata (1572-1663), le fils d’un imminent stratège du clan à partir de 1615. L’historien japonais Yamamoto Hirofumi (Yamamoto Hirofumi, Nihonjin no kokoro : bushidô nyûmon, Chûkei éditions, Tôkyô, 2006), constata au cours de ses recherches l’absence, à l’époque moderne, de textes formulant une éthique des guerriers qui auraient pu être accessibles et respectées par le plus grand nombre des samouraïs. Mieux, les rares textes, formulant et dégageant une éthique propre aux samouraïs (le Hagakure de Yamamoto Tsunetomo et les écrits de Yamaga Sôkô) tous deux intégrés dans le canon des textes de l’idéologie du bushidô, n’ont eu aucune influence avant le XXe siècle.

Le terme « bushidô », utilisé en ce sens serait apparue pour la première fois dans le koyo gunkan, la chronique militaire de la province du Kai dirigée par le célèbre clan des Takeda (la chronique a été compilée par Kagenori Obata (1572-1663), le fils d’un imminent stratège du clan à partir de 1615. L’historien japonais Yamamoto Hirofumi (Yamamoto Hirofumi, Nihonjin no kokoro : bushidô nyûmon, Chûkei éditions, Tôkyô, 2006), constata au cours de ses recherches l’absence, à l’époque moderne, de textes formulant une éthique des guerriers qui auraient pu être accessibles et respectées par le plus grand nombre des samouraïs. Mieux, les rares textes, formulant et dégageant une éthique propre aux samouraïs (le Hagakure de Yamamoto Tsunetomo et les écrits de Yamaga Sôkô) tous deux intégrés dans le canon des textes de l’idéologie du bushidô, n’ont eu aucune influence avant le XXe siècle.

If we take these words out of context but relate them to certain ideas held by Mishima, then these worlds can equally equate to the changing landscape of Japan based on skyscrapers and the dilution of faith and philosophy. In other words, maybe Japan had learned everything under the Meiji Restoration based on the hypocrisy of Western, Catholic, and Islamic empires that utilized fear and control at the drop of a hat. Of course, while Islamization followed the Ottomans and Catholicism followed the Spanish – the British view was that you didn’t have to enslave one hundred percent by destroying indigenous faiths. Instead, the essence of the British Empire was to exploit resources at all costs – while destroying the soul of poor indigenous British nationals based on child labor, the workhouse, and a host of other barbaric realities.

If we take these words out of context but relate them to certain ideas held by Mishima, then these worlds can equally equate to the changing landscape of Japan based on skyscrapers and the dilution of faith and philosophy. In other words, maybe Japan had learned everything under the Meiji Restoration based on the hypocrisy of Western, Catholic, and Islamic empires that utilized fear and control at the drop of a hat. Of course, while Islamization followed the Ottomans and Catholicism followed the Spanish – the British view was that you didn’t have to enslave one hundred percent by destroying indigenous faiths. Instead, the essence of the British Empire was to exploit resources at all costs – while destroying the soul of poor indigenous British nationals based on child labor, the workhouse, and a host of other barbaric realities. Mishima said, “If we value so highly the dignity of life, how can we not also value the dignity of death? No death may be called futile.”

Mishima said, “If we value so highly the dignity of life, how can we not also value the dignity of death? No death may be called futile.”

Noboru is fascinated with the sea and ships. He convinces his mother to take him to a port, where a sailor by the name of Ryuji Tsukazaki, second mate aboard a freighter ship, shows him around his ship. The reader is introduced to Ryuji when Fusako invites him to the Kurodas’ home and Noboru observes the two embracing through a hole in the wall behind a chest in his bedroom.

Noboru is fascinated with the sea and ships. He convinces his mother to take him to a port, where a sailor by the name of Ryuji Tsukazaki, second mate aboard a freighter ship, shows him around his ship. The reader is introduced to Ryuji when Fusako invites him to the Kurodas’ home and Noboru observes the two embracing through a hole in the wall behind a chest in his bedroom.

The narrator, Mizoguchi, is physically weak, ugly in appearance, and afflicted with a stutter. This isolates him from others, and he becomes a solitary, brooding child. He first learns of the Golden Temple from his father, a frail country priest, and the image of the temple and its beauty becomes for him an idée fixe. The young Mizoguchi worships his vision of temple, but there are omens of what is to come. When a naval cadet visits his village and notices his stutter, Mizoguchi is resentful and retaliates by defacing the cadet’s prized scabbard. From the beginning, he realizes that the beauty of the temple represents an unattainable ideal: “if beauty really did exist there, it meant that my own existence was a thing estranged from beauty” (21). Over time, this seed in his mind metastasizes and begins to consume him.

The narrator, Mizoguchi, is physically weak, ugly in appearance, and afflicted with a stutter. This isolates him from others, and he becomes a solitary, brooding child. He first learns of the Golden Temple from his father, a frail country priest, and the image of the temple and its beauty becomes for him an idée fixe. The young Mizoguchi worships his vision of temple, but there are omens of what is to come. When a naval cadet visits his village and notices his stutter, Mizoguchi is resentful and retaliates by defacing the cadet’s prized scabbard. From the beginning, he realizes that the beauty of the temple represents an unattainable ideal: “if beauty really did exist there, it meant that my own existence was a thing estranged from beauty” (21). Over time, this seed in his mind metastasizes and begins to consume him. All human beings possess a will to power in the Nietzschean sense. This finds its highest expression in self-actualization and self-mastery, and in the achievements of great artists, thinkers, and leaders, but in its lower forms is embodied by the desire of defective beings to assert themselves at all costs. This is manifested in Mizoguchi’s desire to destroy the temple, which intensifies in proportion to his realization that he will never be able to possess it or approach its beauty.

All human beings possess a will to power in the Nietzschean sense. This finds its highest expression in self-actualization and self-mastery, and in the achievements of great artists, thinkers, and leaders, but in its lower forms is embodied by the desire of defective beings to assert themselves at all costs. This is manifested in Mizoguchi’s desire to destroy the temple, which intensifies in proportion to his realization that he will never be able to possess it or approach its beauty.

B

B