jeudi, 06 février 2020

On The Decline In US Strategic Thinking And The Creation Of False Stereotypes

On The Decline In US Strategic Thinking And The Creation Of False Stereotypes

In early January 2020, the RAND Corporation published its latest research report on Russia entitled “Russia’s Hostile Measures. Combating Russian Gray Zone Aggression Against NATO in the Contact, Blunt, and Surge Layers of Competition”.

The report is made up of four chapters: 1. Russian hostile measures in every context; 2. The evolution and limits of Russian hostile measures; 3. Gray zone cases and actions during high-order war; and 4. Deterring, preventing, and countering hostile measures. There are also two appendices: 1) An evolutionary history of Russia’s hostile measures; and 2) Detailed case studies of Russia’s use of hostile measures.

By the headings alone, it is possible to gauge the kind of psychological effect that the authors of the monograph wanted it to have. They clearly wanted to say that Russia as a political entity is aggressive – it has been that way throughout history and it will continue to be so in the future – and it is therefore vital to prevent such aggression in a variety of ways.

It is also stated that the report was sponsored by the US Army as part of the project “Russia, European Security, and ‘Measures Short of War’” and that the research and analysis was conducted between 2015 and 2019. The purpose of the project was “to provide recommendations to inform the options that the Army presents to the National Command Authorities to leverage, improve upon, and develop new capabilities and address the threat of Russian aggression in the form of measures short of war.” In addition, the report was reviewed by the US Department of Defense between January and August 2019, and the RAND Corporation conducted seminars in European NATO member countries as part of the project. Notably, one of the first events was held in February 2016 at Cambridge University, which has become a kind of hub for visiting experts from other countries.

From a scientific perspective, the report’s authors adhere to the classical American school – Kremlinologist George Kennan and his concepts are mentioned, as is Jack Snyder, who coined the term “strategic culture” on the basis of nuclear deterrence. The sources referred to in the footnotes are also mostly American, with the exception of a few translated texts by Russian authors (both patriots and liberal pro-Westerners) and official government bodies. But, on the whole, the report is of rather poor scientific value.

Two interrelated topics are discussed in the first chapter that, over the last five years, the West’s military and political communities have steadfastly associated with Russia – the grey zone and hybrid warfare. It is clear that these phrases are being used intentionally, as is the term “measures”, since Western centres are trying to use the terminological baggage of the Soviet past alongside their own modern concepts, especially when it refers to military or security agencies (the term “active measures” was used by the USSR’s KGB from the 1970s onwards). It is noted that NATO officially began to use the term “hybrid warfare” with regard to Russia following the events in Crimea in 2014.

Examples given of active measures during the Cold War include: assassination (the murder of Stepan Bandera); destabilisation (training Central and South American insurgents with Cuba in the 1980s); disinformation (spreading rumours through the German media that the US developed AIDS as a biological weapon; disseminating information about CIA sabotage efforts); proxy wars (Vietnam, Angola); and sabotage (creating panic in Yugoslavia in 1949).

Although America’s involvement in such techniques was more sophisticated and widespread (from establishing death squads in Latin America and supporting the Mujahideen in Afghanistan by way of Pakistan to the Voice of America radio programmes and governing remotely during riots in Hungary and Czechoslovakia) and certain facts about the work of Soviet intelligence agencies are well known, the examples cited of measures taken by the USSR are not backed up by authoritative sources.

Russia’s hostile measures in Europe

Other methods for influencing the report’s target audience are noticeable, and these have been used before to create a negative image of Russia. These include a comparison with the actions of terrorist organisations: “the shock and awe generated by the blitzkrieg-like success of Russia in Crimea and the Islamic State in Iraq generated considerable analytic excitement. A few early accounts suggested that Russia had invented a new way of war” (p. 6).

According to the authors, the West had already clearly decided what to call Russia’s actions in 2016. With that in mind:

“– Gray zone hostilities are nothing new, particularly for Russia.

– Russia will continue to apply these tactics, but its goals and means are limited.

– Deterring, preventing, or countering so-called gray zone behavior is difficult” (p. 7).

The report also states that many articles on the subject written in 2014 and 2015 contained overly exaggerated value judgements, but, in 2017, analyses of the grey zone and hybrid warfare shifted towards a balanced and objective view of Russian power.

This should also be queried, because a relatively large number of reports and papers on similar topics have been published since 2017. Even the US national defence and security strategies had a blatantly distorted view of both Russia and other countries.

The only thing one can possibly agree with is the coining of the new term “hybrid un-war”, which emerged from debates in recent years. It’s true that Russia is employing certain countermeasures, from modernising its armed forces to imposing counter sanctions, but many of these are in response to provocative actions by the West or are linked to planned reforms. Evidently, the authors understand that it will be difficult to make unfounded accusations, so they are covering themselves in advance by choosing a more suitable word. Against the general backdrop, however, the reference to an “un-war” seems rather vague.

It should be noted that the first appendix contains a list of academic literature on Soviet and Russian foreign policy that supposedly backs up the authors’ opinions on the methods of political warfare being carried out by Russia (and the USSR before it). Among the most important sources are declassified CIA reports and assessments, along with similar files from the US National Security Archive that were posted online by staff at George Washington University. Needless to say, the objectivity of documents like these is rather specific.

The section on the institutionalisation and nature of Russian hostile measures is interesting. The authors point out that Russia has an existential fear of NATO and the West as a whole because it has been threatened by external invasion for centuries. The timeline begins in the 13th century with the Mongol invasion that ended with the destruction of Moscow, and it finishes with Germany’s invasion of the USSR and the deaths of 20 million Russians. Interestingly, the 20th century also includes the North Russia intervention by the US and its allies. Such selectivity is surprising, as if there had been no aggression from the Teutonic Order or other wars prior to the 13th century. The 18th century is excluded from the list entirely, yet it was a pivotal era for the Russian state (the Great Northern War, the wars with the Persian and Ottoman empires, the Russo-Swedish War and so on), when numerous external challenges had to be met.

But the report then mentions NATO’s expansion to the East and America’s use of soft-power methods, including the organisation of colour revolutions in the post-Soviet space, where there were Russian client governments. Although it says in justification that NATO never threatened Russia, it emphasises that NATO’s physical infrastructure and military capabilities forced Moscow to include it on its list of national security threats.

In addition to this, the RAND experts point out Russia’s worry over internal revolt. The report once again provides a selective timeline that includes the Decembrist revolt, colour revolutions in the post-Soviet space, and even the war in Syria, which is described as “a long-standing Russian client state” (p. 15).

It then goes on to paraphrase Dmitri Trenin, director of the Carnegie Moscow Centre, who said that the Kremlin fears US intervention and the Russian General Staff fears NATO intervention. It therefore follows that “[t]he perception of a threat influences behavior, even if the perceived threat is overblown or nonexistent. Whether or not one believes that worry, or even paranoia, is the primary driver behind current Russian actions in the gray zone and its preparations for high-order war, this essential element of Russian culture demands an objective and thoughtful accounting” (p. 16).

Following this is a description of the security apparatus that carries out hostile measures. A line is drawn between the NKVD, KGB and FSB, and these are also joined by the SVR, for some reason. The armed forces are considered separately, with a focus on the GRU and special forces. And that’s it. There is no mention of the police, the public prosecutor’s office and the investigative committee or even the FSO. It is even a bit strange not to see “Russian hackers” and private military companies, which are a regular feature of such reports. It is also noted that current actions are nothing other than a “continuity of the Brezhnev Doctrine” (p. 21), which only exists in the imaginations of Western experts. The authors themselves acknowledge further on that this is how speeches by Brezhnev and Gromyko, quoted in Pravda in 1968, were interpreted by Western observers.

On the next page, it claims that neo-nationalism is an ideological tool for Russian foreign policy! And there is another rather interesting passage further on, when the authors of the report confuse former Russian Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov with former Russian Defence Minister Sergey Ivanov. Although they mention Igor Ivanov’s name in the context of grand strategy, foreign policy and neo-nationalism in Russia, they then refer to “Ivanov’s own 2003 military doctrine and reform plan” (p. 23). And this is given as confirmation of the aggressive neo-nationalist strategy that, according to the authors, is associated with Igor Ivanov! If the authors had been more attentive, they would have discovered that, at that time, Igor Ivanov was serving as the head of the foreign ministry, while the defence minister was Sergey Ivanov. Especially as they make reference to an article by a Western author, who, in 2004, analysed the Russian defence ministry’s reform and uses the right name (Matthew Bouldin, “The Ivanov Doctrine and Military Reform: Reasserting Stability in Russia,” Journal of Slavic Military Studies, Vol. 17, No. 4, 2004). It seems that, when compiling the report, they simply copied an additional footnote to lend extra weight, but it was the wrong one.

It goes without saying that such a large number of errors undermines the entire content of the report. And this raises a logical question: what was the authors’ intention? To earn their money by throwing a bunch of quotes together or to try and understand the issues that exist in relations between Russia and the West?

Judging by the number of mistakes and biased assessments, it was most probably the former. There are also traces of a clear strategic intent, however.

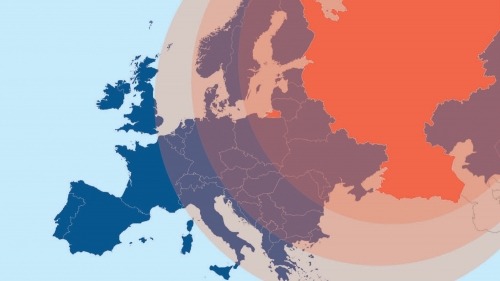

This can be seen in the description of the grey zone where Russia is actively operating, because the case studies provided as examples of Russia’s activities in the grey zone are its bilateral relations with Moldova (1990–2016), Georgia (2003–2012), Estonia (2006–2007), Ukraine (2014–2016), and Turkey (2015–2016). According to the authors, then, the grey zone is independent sovereign states, including NATO members! And virtually all of them, with the exception of Turkey, are former post-Soviet countries that are in the sphere of Russia’s natural interests.

As for the methods that Russia allegedly employs, these are all heaped together in a big pile: economic embargoes, which have been imposed by Moscow for various reasons (the ban on wine imports from Moldova and Georgia, for example), support of certain political parties, compatriot policies, and diplomatic statements and sanctions (in relation to Turkey, for example, when a Russian plane was shot down over Syria).

Eventually, the report states: “Our five cases may not stand alone as empirical evidence, but they are broadly exemplary of historical trends. […] Russia applies hostile measures successfully but typically fails to leverage tactical success for long-term strategic gain” (p. 49).

From this, the report concludes that:

“1. Russia consistently reacts with hostile measures when it perceives threats.

- Both opportunism and reactionism drive Russian behavior.

- Russian leaders often issue a public warning before employing hostile measures.

- Short- and long-term measures are applied in mutually supporting combination.

- Diplomatic, information, military, and economic means are used collectively.

- Russia emphasizes information, economic, and diplomatic measures, in that order.

- All arms of the government are used to apply hostile measures, often in concert.”

In their description of Russia’s actions, the RAND experts even go so far as to include resistance to the Wehrmacht in occupied Soviet territories during the Second World War, including the partisan underground, as an example of “Soviet hostile measures”, when “Soviet agents aggressively undermined the German economic program […] in the western occupied zone”! (p. 53). The report then goes on to say: “By the time the Soviets shifted to the counteroffensive, they had generated a massive, multilayered hostile-measures apparatus tailored to complement conventional military operations” (p. 53) and “[f]ull-scale sabotage, propaganda, and intelligence operations continued apace throughout the war” (p. 54). Immediately after this ludicrous statement is a paragraph on the actions of the KGB and GRU against insurgents in Afghanistan. This is then followed by an attempt to predict what Russia will do in the future.

So, from the report we can draw the following conclusions. First, it is unclear why the “hostile measures” described in the report include fairly standard practices from international experience that are also used in the West as democratic norms. Second, the report contains a number of distorted facts, errors, incorrect assessments and conclusions that undoubtedly undermine its content. Third, such specific content with attempts to manipulate history is clearly intended to further tarnish Russia’s image, since it will be quoted by other researchers and academics in the future, including by way of mutual citation to reinforce credibility. Fourth, if the US command and NATO are going to perceive this mix of speculation, phobias and value judgements as basic knowledge, then it really could lead to a further escalation, although the hostile measures will be employed by the US and NATO. Fifth, the report clearly adheres to the methodology of the liberal interventionist school, which is somewhat strange for a study that claims to be a guide to action for the military, since the US military usually adheres to the school of political realism, in accordance with which the interests of other states must be respected. And since Russia’s sphere of interests is included in the grey zone, this suggests attempts to deny Russia its geopolitical interests.

Source: OrientalReview

00:52 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : états-unis, leonid savin, géopolitique, géostratégie, politique internationale, actualité, russie, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les commentaires sont fermés.