“Agitprop has been the method for destroying America’s culture and rebuilding it as Cultural Marxism.”

John Harmon McElroy, Agitprop in America

Agitprop in America

Agitprop in America

John Harmon McElroy

Arktos, 2020

“You can live with the loss of certainty, but not of belief.” So begins John Harmon McElroy’s recently-published Agitprop in America, an almost 400-page book on America’s increasing distance from former beliefs, wholesale adoption of new ones, and the methods by which this transformation was brought about. A cultural historian, McElroy is a professor emeritus of the University of Arizona and was a Fulbright scholar at universities in Spain and Brazil. I suspect Agitprop in America is an exercise in catharsis for the author. During the course of the volume McElroy is clearly, to borrow Melville’s famous words, “driving off the spleen,” by which I mean that he is dispensing with many years of excess feelings of irritation, built up over a career in decaying academia. In Agitprop in America, McElroy takes aim at a succession of modern academia’s sacred cows, with chapters covering Marxist history and propaganda techniques, “social justice” activism, mandatory diversity, political correctness, free speech, snowflake culture, government spending, and the dominance of Cultural Marxism in the American education system. One of the book’s more unique features is a 107-page lexicon of 234 terms (from Ableism to Xenophobia) explaining the invention and employment of language as a method of cultural transformation via agitprop. The book is written in a terse, urgent style reminiscent of Hillaire Belloc, and McElroy comes across confident, bullish, and confrontational, all of which contributes character to what is one of the more original and interesting books I’ve read thus far in 2020.

My first impression of Agitprop in America was that it was a kind of throwback to older anti-Communist texts. I mean this in neither a strictly positive nor strictly negative sense, but an understanding and appreciation of the overall intellectual trajectory of the book will demand that this is acknowledged. In the absence of biographical details, I would estimate McElroy to be in his 80s. He comes across as a thoroughly committed Christian and capitalist, and the book itself is dedicated to “Cuba’s Escambray guerrillas who died fighting Fidel Castro’s Marxist tyranny in the 1960s.” As such, the psychology of the book is underpinned by tensions and memories that are either unknown or significantly faded among younger generations, such as McCarthyism, the Bay of Pigs incident, and the Cuban Missile Crisis. That being said, the book is still incredibly contemporary and relevant. This is in large part due to McElroy’s keen ear for contemporary society and politics, as well as the evolving lexicon of Cultural Marxism, which enables him to discuss “woke” culture with the same accuracy and vigor as “class struggle.” I also think that, in an age where it’s becoming commonplace among Rightist millennials to dismiss “Boomers” and throw themselves headlong into a “NazBol” Third Positionism that in some respects rehabilitates or repurposes aspects of Marxism and even the Frankfurt School, it’s beneficial to listen to those with decades of experience in the culture wars. Although I don’t agree with everything McElroy has to say, he is one such individual and he has produced a very useful text.

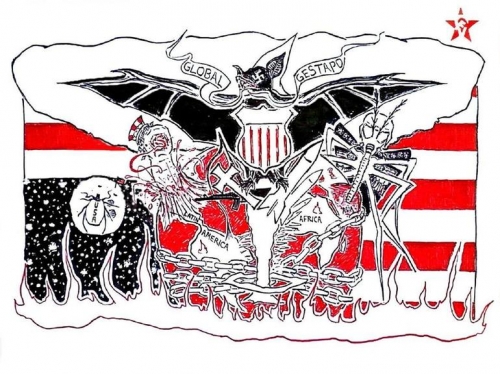

The book opens with the contention that “since the 1960s Marxists and their sympathizers in America have been using agitprop (an integration of intense agitation and propaganda invented by Lenin) to destroy America’s culture and build Cultural Marxism. To do this, agitprop has changed American speech and manipulated cultural values and beliefs.” American history has been rewritten “to make it into a Marxian tale of unmitigated oppression.” American contemporary society has been reinterpreted as the story of “one biologically defined ruling class (straight White males) “victimizing” all other biologically defined classes.” These Marxist dogmas “are causing the destruction of America’s exceptional culture.”

The book opens with the contention that “since the 1960s Marxists and their sympathizers in America have been using agitprop (an integration of intense agitation and propaganda invented by Lenin) to destroy America’s culture and build Cultural Marxism. To do this, agitprop has changed American speech and manipulated cultural values and beliefs.” American history has been rewritten “to make it into a Marxian tale of unmitigated oppression.” American contemporary society has been reinterpreted as the story of “one biologically defined ruling class (straight White males) “victimizing” all other biologically defined classes.” These Marxist dogmas “are causing the destruction of America’s exceptional culture.”

Part I of the book consists of a brief sketch of the historical context of agitprop in America. McElroy does a very capable job of following political correctness from its Soviet and Maoist origins, through the campus agitations of the 1960s, to the “woke” culture warriors of today. Early in the chapter he indulges in some of the “antifa are the real fascists” fluff that one unfortunately expects from older anti-Communists, and he makes one positive reference to the tainted writings of the Jewish neoconservative academic Richard Pipes. But these are brief divergences from an otherwise steady and interesting invective against the corruption of language and the introduction of politically correct culture in the United States. McElroy is at his best when he focuses on the methodology of Culture Marxism, writing:

Instead of overturning the U.S government by force and taking comprehensive control of the United States all at once, the Counter Culture/Political Correctness Movement has been engaged for the last fifty years in gradually but relentlessly transforming the United States from within little by little, by co-opting its institutions and destroying existing cultural beliefs slowly and methodically, and replacing them with the dogmas of Marxism. (8)

In our current age of declining optimism and rising nihilism, I found McElroy’s persistent belief in American exceptionalism to be somewhat heartening. Although the America of today has thickened and bubbled into a globalist empire, it was indeed founded, as McElroy reminds us “on belief in man’s unalienable birthright to life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness, and government by consent of the governed.” The author is both saddened and angered to see the promise of the “American Dream” come under sustained attack from both internal and external enemies, and while we can make the argument for a more critical or nuanced interrogation of such concepts as the “American Dream” (Tom Sunic’s excellent Homo Americanus is probably unsurpassed in this area), it’s difficult to argue that something special and precious hasn’t been lost in America since the 1950s. Where Sunic and McElroy might agree, with radically different implications, is in their assessment of the nature of American culture through history. Both assert the European origins of American culture, and both assert that it later became essentially non-European. For McElroy, this transition (c. 1800–1950) represents a triumph, with America defining itself against “the aristocratic cultures of Europe based on belief in ruling classes constituted by “noble” and “royal” blood.” For Sunic, the drift away from European culture resulted in hostility to European traditions, and an obsession with “rights” and individualistic consumerism, that has dogged America for over a century and has contributed heavily to its current cultural malaise. Both scholars would find agreement again in the fact America post-1950 has been in the throes of a cultural catastrophe in which Marxism has been pivotal.

The latter section of the first chapter concerns Marxist dogma from Soviet times to the present. McElroy is quite right to point out that historically Marxists argued that deviation from their worldview could represent a “symptom of mental derangement requiring treatment in a psychiatric clinic,” and he places this alongside commentary on how today’s dissidents are presented as “enemies of humanity.” In each case, agitprop develops an environment in which dissent is viewed and portrayed as “a kind of irrational, anti-science behavior.” The key to the success of Cultural Marxist agitprop is its “intrinsic deceptiveness.” McElroy writes,

Political correctness represents itself as a champion of fundamental American values. That brazen pretense, that Marxism is identical to American liberalism and progressivism, is why the Counter Culture/Political Correctness movement has had so much success in the United States. (22)

Drawing on Saul Alinsky’s infamous Rules for Radicals, McElroy explains how Cultural Marxists provoke their opponents into reacting (e.g. threatening to take down historical monuments, ordering “gay cakes”) and then denounce them as irrational “reactionaries.” Another tactic is to create problems, or interpret problems, in such a manner that permits the proposal of Marxist “solutions.” I thought that an analysis of Alinsky’s works might provoke a deeper reading from McElroy, who writes that Alinsky was “an atheist.” In fact, Alinsky was an agnostic who, when asked specifically about religion, would always reply that he was Jewish. This error is indicative of a broader blind spot in the text — the ethnic component of anti-American activism. This blind spot manifests more subtly throughout the lexicon of Cultural Marxist terms that comprises the middle of the book. Quite frankly, when one actually looks at the individuals who have coined or popularized many of these genuinely novel agitprop terms (e.g. ‘homophobia’ by George Weinberg, ‘deconstructionism’ by Jacques Derrida, ‘racism’ by Magnus Hirschfeld and Leon Trotsky, ‘transgender’ by Magnus Hirschfeld and later Harry Benjamin, ‘sex work” and ‘sex worker’ by Carol Leigh, ‘cultural pluralism’ by Horace Kallen), they emerge almost exclusively as Jews. It’s a simple and unavoidable fact that Jews have been at the forefront of changing “ways of seeing” by first changing “ways of describing.” I agree with McElroy that we shouldn’t call anti-American agitators “liberals,” and that “Leftists” also leaves a lot unsaid. McElroy, however, proposes “PC Marxists,” which I feel doesn’t get any closer to the mark.

The question presenting itself is: Does this blind spot hinder the usefulness of the text? I don’t think so. Agitprop in America can be read by the well-informed, such as readers of this website, who can fill in certain blanks (as I have above) from their own extensive reading and derive a great deal of knowledge and pleasure from the book. McElroy opines that the two greatest identifying attitudinal markers of “PC Marxism” are hypocrisy and paranoia. He writes that they vigorously enforce “separation of church and state,” and fully embrace “crony capitalism.” Rather than being genuine Americans, they merely “go about in the guise” of the everyday man, while looking down on those who dissent from their thinking in the belief they’re “stupid.” They “relentlessly insist on social justice.” Who does this sound like? And, so you see, specifics of nomenclature aside, the book lends itself to an open and usable reading.

The second chapter of the book contains some interesting autobiographical material on McElroy’s early academic career. In 1966, the same year our own Kevin MacDonald graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, McElroy, a newly minted PhD, arrived at the college. McElroy writes, “Without knowing it, I was going to one of the two epicenters of the Counter Culture movement in the Midwest, the other being the University of Michigan.” McElroy became especially fascinated with the chants of student protestors, seeing in their uniformity certain indications of “planning for a nationwide campaign of agitation and propaganda against U.S. military involvement in Vietnam and against America’s cultural beliefs.” The chapter proceeds with a discussion of the mindset and tactics of this early agitprop campaign, with McElroy commenting:

Normal minds of course find it difficult to believe in a “culture war” that has gone on for half a century and that aims to transform the world’s oldest, most successful republic into a center for Cultural Marxism. Because the project is so audacious, it has taken many middle-class Americans a long time to believe such a movement exists; and many middle-class Americans apparently still refuse to believe a systematic assault is underway on American culture and has been going on in America for fifty years. But whether you believe it or not, a culture war is in progress in America, as evidenced by the fact that many Americans now prefer the dogmas of Marxism to the beliefs of American culture.

The second part of the book consists of the above-mentioned 107-page lexicon of 234 terms explaining the invention and employment of language as a method of cultural transformation via agitprop. The lexicon itself is preceded by two brief explanatory chapters on “Politically Correct Language as a Means of Revolution,” and “Terms Related to and Used by the Counter Culture/Political Correctness Movement.” The first of these chapters is very heavily focused on McElroy’s belief that we should once more refer to Blacks as “Negroes” or “Negro Americans.” For McElroy, the term “African-American” is an “agitprop substitute” designed to make Whites and Blacks constantly aware “that most Negro Americans have remote ancestors brought to America from Africa in chains as slaves.” The author spends several pages thrashing out this issue, which left me quite unsure that this particular issue would be the metaphorical hill I’d personally choose to die on. McElroy comes from a generation in which the term “Negro” probably retained a semblance of tradition and even charm about it, whereas it’s now fallen so completely out of use that a resurrection of the term could only be perceived by all sides as something negative. Again, I actually do sympathize with the central thrust of McElroy’s meaning here. I’m just not convinced I’d base my war on agitprop so strongly in this particular issue.

My misgivings on this point carried through somewhat to the lexicon itself, which is overwhelmingly good but contains some dubious entries. McElroy must first be commended for compiling such an extension list of terms, which is, as far as I’m aware, the only ‘Rightist” lexicon of Cultural Marxist agitprop in existence. Each term comes with commentary, with some only a few sentences in length and others a few pages. A few examples should suffice in order to give a flavor of the style:

Ableism

A faux bias cooked up by PC agitprop, ableism is an alleged prejudice against a person with a disability as, for instance, refusing to hire someone with a stutter or substandard comprehension of spoken English as an office receptionist. Not hiring a person with a patently disqualifying deficiency constitutes the prejudice of “ableism,” according to PC Marxists. See entry on “Sizeism.”

Person of Size

Someone who is extremely obese is a “person of size” in PC talk. The euphemism was invented as part of agitprop’s insistence on the need for sensitive, inoffensive diction.

Relationship

The expression “having a relationship” means in PC parlance having sex with the same partner for a significant length of time without getting married. To a PC Marxist, “having a relationship” is preferable to having a marriage because it forestalls family formation.

Right-Wing Extremism

“Right-wing extremism” is one of the labels PC Marxists use to criticize their opponents, whom they regard as “extreme” because they put the interests of their nation above the revolutionary dogmas of global Marxism.

Sexual Orientation

This is the PC euphemism for homosexuality. The euphemism was coined to avoid the use of the words “homosexual” and “homosexuality.” The phrase “sexual orientation” allows persons who are politically correct to praise and promote homosexual behavior without having to use the terms “homosexual” or “homosexuality,” which are loaded with a historical burden of moral disapproval. The term “sexual orientation,” however, has a scientific ring to it implying that homosexuality is merely one of various “orientations” toward sexual activity, so that no one should object to it. Homosexual practices ought to be considered as any other erotic activity. This is the argument agitprop in America is making in its revolutionary assault.

With over 230 terms covered, many of them very current in contemporary internet culture, McElroy is to be applauded for his effort in both compiling the list and keeping his finger on the agitprop pulse. The few dubious entries emerge from McElroy’s apparently fundamentalist Christian beliefs, which lead him to a few scathing remarks on evolution, the Big Bang theory, etc. This is McElroy’s book, and it’s his right to wax lyrical on some matters that are clearly close to his heart. I’m certainly not disparaging his approach, but I do think that this might alienate readers who are of a more scientific and less spiritual mindset. That being said, he has produced a great piece of work in this lexicon.

The third section of the book is probably my favorite, and McElroy demonstrates the best of his reading and understanding here. The section consists of commentaries/chapters covering “seven related revolutionary concepts that PC agitprop has imposed on America.” These are “Biological Class Consciousness,” “Social Justice,” “Mandatory Diversity,” a politics of double standards, mass indoctrination on “sensitivity,” censorship and the policing of speech, and the promotion of a sterile and self-obsessed atheism. Of these, the first is one of the best, with McElroy remarking:

Now, after five decades of relentless Marxist agitation and propaganda promoting biological class consciousness in America, courses on U.S. history and Western civilization have dwindled and all but disappeared at American colleges and universities while courses on biological class consciousness have proliferated. Everywhere today in U.S. institutions of higher education, one finds courses and degree programs in Women’s Studies, African-American Studies, Mexican-American Studies, and LGBT studies. And as college and university faculties have become more uniform in their Political Correctness, the courses on U.S. history and Western civilization which remain in the curriculum are almost invariably taught from the point of view of Marxian class struggle, which is to say from the standpoint that straight “Euro-American” males (SEAMs) comprise a ruling class which has “victimized” women, negro Americans, Hispanics, Asian-Americans, homosexuals, and other biologically defined classes. College students today are being taught to hate SEAMs as a class for the “victimisation” they have allegedly inflicted on all other biological classes in America.(180)

McElroy is equally on point when it comes to “social justice,” suggesting that the term really refers to “the idea of preferential treatment for members of allegedly oppressed classes. It is justice dispensed according to class history … “Social justice” is political justice. It expresses political favoritism that will advance the revolution.” The author is also good on the subject of “Mandatory Diversity,” pointing out just how incentivized this has become in our culture and economy:

A reputation for being “diverse” is something institutions throughout America today are eager to acquire. Being “diverse” has become a political, economic, and academic requirement, a much-coveted accolade, a shibboleth attesting to one’s Political Correctness. (220)

On “sensitivity” agitprop, McElroy observes that “the real purpose of the sensitivity game is intimidation.” Enforced “soft language” for protected groups creates an atmosphere in which deviation into normal speech can be chastized as hateful, unfair, and bigoted. The wider the sensitivity net (e.g. embracing the fat, the ugly, etc.) then the more successful will be the broader cultural strategy. It is an offensive built on “not offending.” The same themes are evident in censorship and the policing of speech.

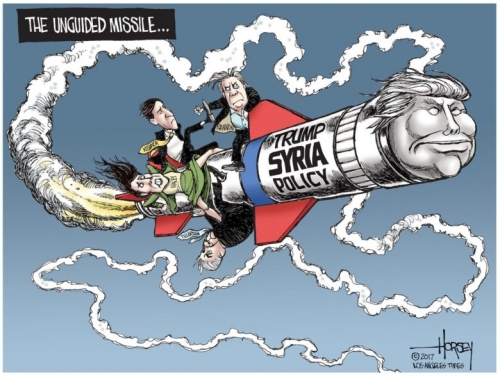

The final section of the book consists of five short chapters on differing subjects. The first is a commentary on “The Failure of Marxism in the USSR and Successes of PC Marxism in America” which combines an interesting historical overview with a quite strident attack on the Obama years. The next chapter is a brief but lucid essay on how agitprop and PC Marxism has influenced U.S. government spending. The third, and shortest chapter in this section is an attempted rebuttal of the idea that America has become an imperialist nation. I tend to disagree with McElroy somewhat here, not because I believe America has an empire in the conventional sense, but because I believe it’s self-evident that elements of the U.S. government, most notably the neocons, have increasingly steered the country into a foreign interventionist position built around the idea of sustaining global finance capitalism and the state of Israel. Since McElroy’s musings on this topic are limited to a few pages, I was, however, spared any lasting distaste.

The final section of the book consists of five short chapters on differing subjects. The first is a commentary on “The Failure of Marxism in the USSR and Successes of PC Marxism in America” which combines an interesting historical overview with a quite strident attack on the Obama years. The next chapter is a brief but lucid essay on how agitprop and PC Marxism has influenced U.S. government spending. The third, and shortest chapter in this section is an attempted rebuttal of the idea that America has become an imperialist nation. I tend to disagree with McElroy somewhat here, not because I believe America has an empire in the conventional sense, but because I believe it’s self-evident that elements of the U.S. government, most notably the neocons, have increasingly steered the country into a foreign interventionist position built around the idea of sustaining global finance capitalism and the state of Israel. Since McElroy’s musings on this topic are limited to a few pages, I was, however, spared any lasting distaste.

—The book then nears its end with a very good chapter on “PC Marxist Dominance in U.S. Public Schools,” before closing with a very pro-Trump chapter on “The Significance of the 2016 Presidential Election.” I was ambivalent about this last chapter because it lacks the nuanced and qualified approach to Trump’s 2016 win that is surely now, in light of a succession of policy failures and absences, much-deserved. Part of me wishes I could share McElroy’s optimism, and I laud any man of his advanced age for avoiding the temptation of observing it all with jaded distance. But I cannot, having considered all available evidence and precedence, share his persistent belief in the MAGA phenomenon.

Final Reflection on Agitprop in America

John Harmon McElroy’s work of catharsis is a worthy addition to the Arktos library, and offers an original and multifaceted new approach to the subject of America’s undeniable and ongoing decay. At almost 400 pages of commentaries on numerous subjects, including a large lexicon of Cultural Marxist terms, the book certainly represents value for money and will consume many hours of study. Of course, it doesn’t have “all the answers,” something it has in common with the vast majority of political texts on the market, but it does approach a normally pessimistic subject with intellectual vigor, aggression, confidence, and even optimism. It’s a book worthy of being “balanced out” by the later reading of another text like Sunic’s Homo Americanus, and I think readers can gain much from such an exercise. Readers could also benefit by conducting some of their own research into the origins of certain agitprop terms. McElroy includes several blank pages at the end of his book for “notes,” which could be put to use in this manner. As hinted at earlier in this review, I guarantee that readers will find some predictable but useful information in the process.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.