“Agitprop has been the method for destroying America’s culture and rebuilding it as Cultural Marxism.”

John Harmon McElroy, Agitprop in America

Agitprop in America

Agitprop in America

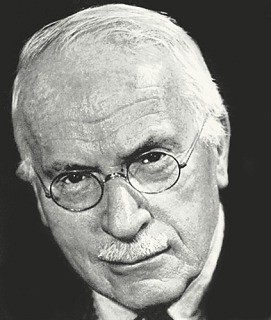

John Harmon McElroy

Arktos, 2020

“You can live with the loss of certainty, but not of belief.” So begins John Harmon McElroy’s recently-published Agitprop in America, an almost 400-page book on America’s increasing distance from former beliefs, wholesale adoption of new ones, and the methods by which this transformation was brought about. A cultural historian, McElroy is a professor emeritus of the University of Arizona and was a Fulbright scholar at universities in Spain and Brazil. I suspect Agitprop in America is an exercise in catharsis for the author. During the course of the volume McElroy is clearly, to borrow Melville’s famous words, “driving off the spleen,” by which I mean that he is dispensing with many years of excess feelings of irritation, built up over a career in decaying academia. In Agitprop in America, McElroy takes aim at a succession of modern academia’s sacred cows, with chapters covering Marxist history and propaganda techniques, “social justice” activism, mandatory diversity, political correctness, free speech, snowflake culture, government spending, and the dominance of Cultural Marxism in the American education system. One of the book’s more unique features is a 107-page lexicon of 234 terms (from Ableism to Xenophobia) explaining the invention and employment of language as a method of cultural transformation via agitprop. The book is written in a terse, urgent style reminiscent of Hillaire Belloc, and McElroy comes across confident, bullish, and confrontational, all of which contributes character to what is one of the more original and interesting books I’ve read thus far in 2020.

My first impression of Agitprop in America was that it was a kind of throwback to older anti-Communist texts. I mean this in neither a strictly positive nor strictly negative sense, but an understanding and appreciation of the overall intellectual trajectory of the book will demand that this is acknowledged. In the absence of biographical details, I would estimate McElroy to be in his 80s. He comes across as a thoroughly committed Christian and capitalist, and the book itself is dedicated to “Cuba’s Escambray guerrillas who died fighting Fidel Castro’s Marxist tyranny in the 1960s.” As such, the psychology of the book is underpinned by tensions and memories that are either unknown or significantly faded among younger generations, such as McCarthyism, the Bay of Pigs incident, and the Cuban Missile Crisis. That being said, the book is still incredibly contemporary and relevant. This is in large part due to McElroy’s keen ear for contemporary society and politics, as well as the evolving lexicon of Cultural Marxism, which enables him to discuss “woke” culture with the same accuracy and vigor as “class struggle.” I also think that, in an age where it’s becoming commonplace among Rightist millennials to dismiss “Boomers” and throw themselves headlong into a “NazBol” Third Positionism that in some respects rehabilitates or repurposes aspects of Marxism and even the Frankfurt School, it’s beneficial to listen to those with decades of experience in the culture wars. Although I don’t agree with everything McElroy has to say, he is one such individual and he has produced a very useful text.

The book opens with the contention that “since the 1960s Marxists and their sympathizers in America have been using agitprop (an integration of intense agitation and propaganda invented by Lenin) to destroy America’s culture and build Cultural Marxism. To do this, agitprop has changed American speech and manipulated cultural values and beliefs.” American history has been rewritten “to make it into a Marxian tale of unmitigated oppression.” American contemporary society has been reinterpreted as the story of “one biologically defined ruling class (straight White males) “victimizing” all other biologically defined classes.” These Marxist dogmas “are causing the destruction of America’s exceptional culture.”

The book opens with the contention that “since the 1960s Marxists and their sympathizers in America have been using agitprop (an integration of intense agitation and propaganda invented by Lenin) to destroy America’s culture and build Cultural Marxism. To do this, agitprop has changed American speech and manipulated cultural values and beliefs.” American history has been rewritten “to make it into a Marxian tale of unmitigated oppression.” American contemporary society has been reinterpreted as the story of “one biologically defined ruling class (straight White males) “victimizing” all other biologically defined classes.” These Marxist dogmas “are causing the destruction of America’s exceptional culture.”

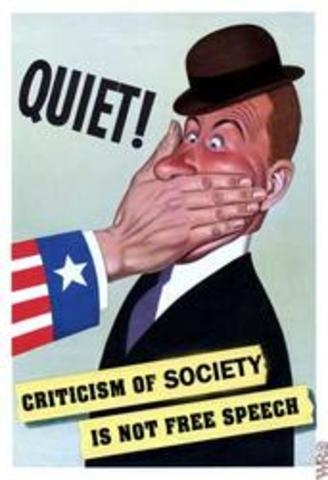

Part I of the book consists of a brief sketch of the historical context of agitprop in America. McElroy does a very capable job of following political correctness from its Soviet and Maoist origins, through the campus agitations of the 1960s, to the “woke” culture warriors of today. Early in the chapter he indulges in some of the “antifa are the real fascists” fluff that one unfortunately expects from older anti-Communists, and he makes one positive reference to the tainted writings of the Jewish neoconservative academic Richard Pipes. But these are brief divergences from an otherwise steady and interesting invective against the corruption of language and the introduction of politically correct culture in the United States. McElroy is at his best when he focuses on the methodology of Culture Marxism, writing:

Instead of overturning the U.S government by force and taking comprehensive control of the United States all at once, the Counter Culture/Political Correctness Movement has been engaged for the last fifty years in gradually but relentlessly transforming the United States from within little by little, by co-opting its institutions and destroying existing cultural beliefs slowly and methodically, and replacing them with the dogmas of Marxism. (8)

In our current age of declining optimism and rising nihilism, I found McElroy’s persistent belief in American exceptionalism to be somewhat heartening. Although the America of today has thickened and bubbled into a globalist empire, it was indeed founded, as McElroy reminds us “on belief in man’s unalienable birthright to life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness, and government by consent of the governed.” The author is both saddened and angered to see the promise of the “American Dream” come under sustained attack from both internal and external enemies, and while we can make the argument for a more critical or nuanced interrogation of such concepts as the “American Dream” (Tom Sunic’s excellent Homo Americanus is probably unsurpassed in this area), it’s difficult to argue that something special and precious hasn’t been lost in America since the 1950s. Where Sunic and McElroy might agree, with radically different implications, is in their assessment of the nature of American culture through history. Both assert the European origins of American culture, and both assert that it later became essentially non-European. For McElroy, this transition (c. 1800–1950) represents a triumph, with America defining itself against “the aristocratic cultures of Europe based on belief in ruling classes constituted by “noble” and “royal” blood.” For Sunic, the drift away from European culture resulted in hostility to European traditions, and an obsession with “rights” and individualistic consumerism, that has dogged America for over a century and has contributed heavily to its current cultural malaise. Both scholars would find agreement again in the fact America post-1950 has been in the throes of a cultural catastrophe in which Marxism has been pivotal.

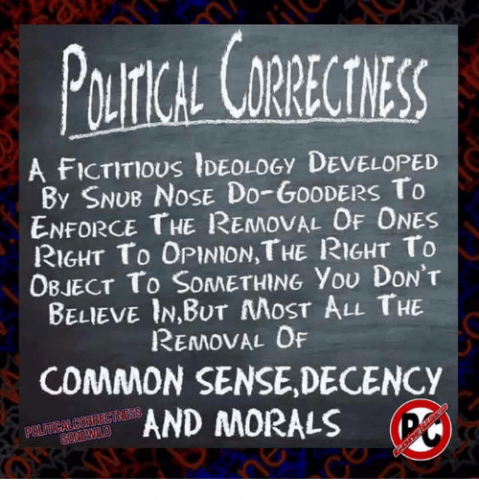

The latter section of the first chapter concerns Marxist dogma from Soviet times to the present. McElroy is quite right to point out that historically Marxists argued that deviation from their worldview could represent a “symptom of mental derangement requiring treatment in a psychiatric clinic,” and he places this alongside commentary on how today’s dissidents are presented as “enemies of humanity.” In each case, agitprop develops an environment in which dissent is viewed and portrayed as “a kind of irrational, anti-science behavior.” The key to the success of Cultural Marxist agitprop is its “intrinsic deceptiveness.” McElroy writes,

Political correctness represents itself as a champion of fundamental American values. That brazen pretense, that Marxism is identical to American liberalism and progressivism, is why the Counter Culture/Political Correctness movement has had so much success in the United States. (22)

Drawing on Saul Alinsky’s infamous Rules for Radicals, McElroy explains how Cultural Marxists provoke their opponents into reacting (e.g. threatening to take down historical monuments, ordering “gay cakes”) and then denounce them as irrational “reactionaries.” Another tactic is to create problems, or interpret problems, in such a manner that permits the proposal of Marxist “solutions.” I thought that an analysis of Alinsky’s works might provoke a deeper reading from McElroy, who writes that Alinsky was “an atheist.” In fact, Alinsky was an agnostic who, when asked specifically about religion, would always reply that he was Jewish. This error is indicative of a broader blind spot in the text — the ethnic component of anti-American activism. This blind spot manifests more subtly throughout the lexicon of Cultural Marxist terms that comprises the middle of the book. Quite frankly, when one actually looks at the individuals who have coined or popularized many of these genuinely novel agitprop terms (e.g. ‘homophobia’ by George Weinberg, ‘deconstructionism’ by Jacques Derrida, ‘racism’ by Magnus Hirschfeld and Leon Trotsky, ‘transgender’ by Magnus Hirschfeld and later Harry Benjamin, ‘sex work” and ‘sex worker’ by Carol Leigh, ‘cultural pluralism’ by Horace Kallen), they emerge almost exclusively as Jews. It’s a simple and unavoidable fact that Jews have been at the forefront of changing “ways of seeing” by first changing “ways of describing.” I agree with McElroy that we shouldn’t call anti-American agitators “liberals,” and that “Leftists” also leaves a lot unsaid. McElroy, however, proposes “PC Marxists,” which I feel doesn’t get any closer to the mark.

The question presenting itself is: Does this blind spot hinder the usefulness of the text? I don’t think so. Agitprop in America can be read by the well-informed, such as readers of this website, who can fill in certain blanks (as I have above) from their own extensive reading and derive a great deal of knowledge and pleasure from the book. McElroy opines that the two greatest identifying attitudinal markers of “PC Marxism” are hypocrisy and paranoia. He writes that they vigorously enforce “separation of church and state,” and fully embrace “crony capitalism.” Rather than being genuine Americans, they merely “go about in the guise” of the everyday man, while looking down on those who dissent from their thinking in the belief they’re “stupid.” They “relentlessly insist on social justice.” Who does this sound like? And, so you see, specifics of nomenclature aside, the book lends itself to an open and usable reading.

The second chapter of the book contains some interesting autobiographical material on McElroy’s early academic career. In 1966, the same year our own Kevin MacDonald graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, McElroy, a newly minted PhD, arrived at the college. McElroy writes, “Without knowing it, I was going to one of the two epicenters of the Counter Culture movement in the Midwest, the other being the University of Michigan.” McElroy became especially fascinated with the chants of student protestors, seeing in their uniformity certain indications of “planning for a nationwide campaign of agitation and propaganda against U.S. military involvement in Vietnam and against America’s cultural beliefs.” The chapter proceeds with a discussion of the mindset and tactics of this early agitprop campaign, with McElroy commenting:

Normal minds of course find it difficult to believe in a “culture war” that has gone on for half a century and that aims to transform the world’s oldest, most successful republic into a center for Cultural Marxism. Because the project is so audacious, it has taken many middle-class Americans a long time to believe such a movement exists; and many middle-class Americans apparently still refuse to believe a systematic assault is underway on American culture and has been going on in America for fifty years. But whether you believe it or not, a culture war is in progress in America, as evidenced by the fact that many Americans now prefer the dogmas of Marxism to the beliefs of American culture.

The second part of the book consists of the above-mentioned 107-page lexicon of 234 terms explaining the invention and employment of language as a method of cultural transformation via agitprop. The lexicon itself is preceded by two brief explanatory chapters on “Politically Correct Language as a Means of Revolution,” and “Terms Related to and Used by the Counter Culture/Political Correctness Movement.” The first of these chapters is very heavily focused on McElroy’s belief that we should once more refer to Blacks as “Negroes” or “Negro Americans.” For McElroy, the term “African-American” is an “agitprop substitute” designed to make Whites and Blacks constantly aware “that most Negro Americans have remote ancestors brought to America from Africa in chains as slaves.” The author spends several pages thrashing out this issue, which left me quite unsure that this particular issue would be the metaphorical hill I’d personally choose to die on. McElroy comes from a generation in which the term “Negro” probably retained a semblance of tradition and even charm about it, whereas it’s now fallen so completely out of use that a resurrection of the term could only be perceived by all sides as something negative. Again, I actually do sympathize with the central thrust of McElroy’s meaning here. I’m just not convinced I’d base my war on agitprop so strongly in this particular issue.

My misgivings on this point carried through somewhat to the lexicon itself, which is overwhelmingly good but contains some dubious entries. McElroy must first be commended for compiling such an extension list of terms, which is, as far as I’m aware, the only ‘Rightist” lexicon of Cultural Marxist agitprop in existence. Each term comes with commentary, with some only a few sentences in length and others a few pages. A few examples should suffice in order to give a flavor of the style:

Ableism

A faux bias cooked up by PC agitprop, ableism is an alleged prejudice against a person with a disability as, for instance, refusing to hire someone with a stutter or substandard comprehension of spoken English as an office receptionist. Not hiring a person with a patently disqualifying deficiency constitutes the prejudice of “ableism,” according to PC Marxists. See entry on “Sizeism.”

Person of Size

Someone who is extremely obese is a “person of size” in PC talk. The euphemism was invented as part of agitprop’s insistence on the need for sensitive, inoffensive diction.

Relationship

The expression “having a relationship” means in PC parlance having sex with the same partner for a significant length of time without getting married. To a PC Marxist, “having a relationship” is preferable to having a marriage because it forestalls family formation.

Right-Wing Extremism

“Right-wing extremism” is one of the labels PC Marxists use to criticize their opponents, whom they regard as “extreme” because they put the interests of their nation above the revolutionary dogmas of global Marxism.

Sexual Orientation

This is the PC euphemism for homosexuality. The euphemism was coined to avoid the use of the words “homosexual” and “homosexuality.” The phrase “sexual orientation” allows persons who are politically correct to praise and promote homosexual behavior without having to use the terms “homosexual” or “homosexuality,” which are loaded with a historical burden of moral disapproval. The term “sexual orientation,” however, has a scientific ring to it implying that homosexuality is merely one of various “orientations” toward sexual activity, so that no one should object to it. Homosexual practices ought to be considered as any other erotic activity. This is the argument agitprop in America is making in its revolutionary assault.

With over 230 terms covered, many of them very current in contemporary internet culture, McElroy is to be applauded for his effort in both compiling the list and keeping his finger on the agitprop pulse. The few dubious entries emerge from McElroy’s apparently fundamentalist Christian beliefs, which lead him to a few scathing remarks on evolution, the Big Bang theory, etc. This is McElroy’s book, and it’s his right to wax lyrical on some matters that are clearly close to his heart. I’m certainly not disparaging his approach, but I do think that this might alienate readers who are of a more scientific and less spiritual mindset. That being said, he has produced a great piece of work in this lexicon.

The third section of the book is probably my favorite, and McElroy demonstrates the best of his reading and understanding here. The section consists of commentaries/chapters covering “seven related revolutionary concepts that PC agitprop has imposed on America.” These are “Biological Class Consciousness,” “Social Justice,” “Mandatory Diversity,” a politics of double standards, mass indoctrination on “sensitivity,” censorship and the policing of speech, and the promotion of a sterile and self-obsessed atheism. Of these, the first is one of the best, with McElroy remarking:

Now, after five decades of relentless Marxist agitation and propaganda promoting biological class consciousness in America, courses on U.S. history and Western civilization have dwindled and all but disappeared at American colleges and universities while courses on biological class consciousness have proliferated. Everywhere today in U.S. institutions of higher education, one finds courses and degree programs in Women’s Studies, African-American Studies, Mexican-American Studies, and LGBT studies. And as college and university faculties have become more uniform in their Political Correctness, the courses on U.S. history and Western civilization which remain in the curriculum are almost invariably taught from the point of view of Marxian class struggle, which is to say from the standpoint that straight “Euro-American” males (SEAMs) comprise a ruling class which has “victimized” women, negro Americans, Hispanics, Asian-Americans, homosexuals, and other biologically defined classes. College students today are being taught to hate SEAMs as a class for the “victimisation” they have allegedly inflicted on all other biological classes in America.(180)

McElroy is equally on point when it comes to “social justice,” suggesting that the term really refers to “the idea of preferential treatment for members of allegedly oppressed classes. It is justice dispensed according to class history … “Social justice” is political justice. It expresses political favoritism that will advance the revolution.” The author is also good on the subject of “Mandatory Diversity,” pointing out just how incentivized this has become in our culture and economy:

A reputation for being “diverse” is something institutions throughout America today are eager to acquire. Being “diverse” has become a political, economic, and academic requirement, a much-coveted accolade, a shibboleth attesting to one’s Political Correctness. (220)

On “sensitivity” agitprop, McElroy observes that “the real purpose of the sensitivity game is intimidation.” Enforced “soft language” for protected groups creates an atmosphere in which deviation into normal speech can be chastized as hateful, unfair, and bigoted. The wider the sensitivity net (e.g. embracing the fat, the ugly, etc.) then the more successful will be the broader cultural strategy. It is an offensive built on “not offending.” The same themes are evident in censorship and the policing of speech.

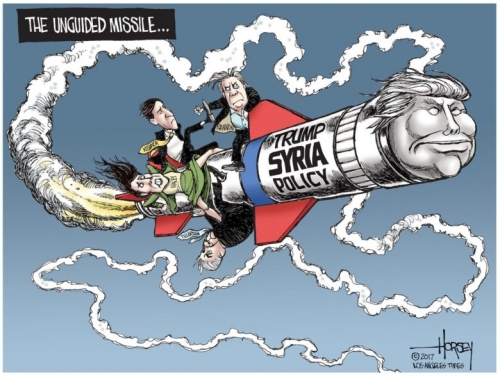

The final section of the book consists of five short chapters on differing subjects. The first is a commentary on “The Failure of Marxism in the USSR and Successes of PC Marxism in America” which combines an interesting historical overview with a quite strident attack on the Obama years. The next chapter is a brief but lucid essay on how agitprop and PC Marxism has influenced U.S. government spending. The third, and shortest chapter in this section is an attempted rebuttal of the idea that America has become an imperialist nation. I tend to disagree with McElroy somewhat here, not because I believe America has an empire in the conventional sense, but because I believe it’s self-evident that elements of the U.S. government, most notably the neocons, have increasingly steered the country into a foreign interventionist position built around the idea of sustaining global finance capitalism and the state of Israel. Since McElroy’s musings on this topic are limited to a few pages, I was, however, spared any lasting distaste.

The final section of the book consists of five short chapters on differing subjects. The first is a commentary on “The Failure of Marxism in the USSR and Successes of PC Marxism in America” which combines an interesting historical overview with a quite strident attack on the Obama years. The next chapter is a brief but lucid essay on how agitprop and PC Marxism has influenced U.S. government spending. The third, and shortest chapter in this section is an attempted rebuttal of the idea that America has become an imperialist nation. I tend to disagree with McElroy somewhat here, not because I believe America has an empire in the conventional sense, but because I believe it’s self-evident that elements of the U.S. government, most notably the neocons, have increasingly steered the country into a foreign interventionist position built around the idea of sustaining global finance capitalism and the state of Israel. Since McElroy’s musings on this topic are limited to a few pages, I was, however, spared any lasting distaste.

—The book then nears its end with a very good chapter on “PC Marxist Dominance in U.S. Public Schools,” before closing with a very pro-Trump chapter on “The Significance of the 2016 Presidential Election.” I was ambivalent about this last chapter because it lacks the nuanced and qualified approach to Trump’s 2016 win that is surely now, in light of a succession of policy failures and absences, much-deserved. Part of me wishes I could share McElroy’s optimism, and I laud any man of his advanced age for avoiding the temptation of observing it all with jaded distance. But I cannot, having considered all available evidence and precedence, share his persistent belief in the MAGA phenomenon.

Final Reflection on Agitprop in America

John Harmon McElroy’s work of catharsis is a worthy addition to the Arktos library, and offers an original and multifaceted new approach to the subject of America’s undeniable and ongoing decay. At almost 400 pages of commentaries on numerous subjects, including a large lexicon of Cultural Marxist terms, the book certainly represents value for money and will consume many hours of study. Of course, it doesn’t have “all the answers,” something it has in common with the vast majority of political texts on the market, but it does approach a normally pessimistic subject with intellectual vigor, aggression, confidence, and even optimism. It’s a book worthy of being “balanced out” by the later reading of another text like Sunic’s Homo Americanus, and I think readers can gain much from such an exercise. Readers could also benefit by conducting some of their own research into the origins of certain agitprop terms. McElroy includes several blank pages at the end of his book for “notes,” which could be put to use in this manner. As hinted at earlier in this review, I guarantee that readers will find some predictable but useful information in the process.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les enfants naissent centrés sur leur moi, principalement parce qu’ils ont « un moi », comme l’a fort bien montré G.K. Chesterton. Et de même que les langues sont mieux apprises dans le jeune âge, la moralité, la tolérance à la critique et les limites portées à son propre désir sont mieux intégrées pendant les premières années. C’est ce que dit le proverbe anglais : « Comme le plant est courbé pousse l’arbre »… Un enfant dont l’énergie naturelle et les instincts tyranniques ne sont pas modérés pourrait ne jamais grandir sans s’en affranchir. Il ne faut pas s’étonner qu’une telle personne développe une forte tendance narcissique, intolérante à la moindre critique et exigeant une validation permanente de sa propre image déifiée.

Les enfants naissent centrés sur leur moi, principalement parce qu’ils ont « un moi », comme l’a fort bien montré G.K. Chesterton. Et de même que les langues sont mieux apprises dans le jeune âge, la moralité, la tolérance à la critique et les limites portées à son propre désir sont mieux intégrées pendant les premières années. C’est ce que dit le proverbe anglais : « Comme le plant est courbé pousse l’arbre »… Un enfant dont l’énergie naturelle et les instincts tyranniques ne sont pas modérés pourrait ne jamais grandir sans s’en affranchir. Il ne faut pas s’étonner qu’une telle personne développe une forte tendance narcissique, intolérante à la moindre critique et exigeant une validation permanente de sa propre image déifiée. Dernière remarque. Le professeur Schwartz relève une observation de l’éditorialiste Megan McArdle. Celle-ci a écrit : « Les étudiants d’aujourd’hui n’expriment pas leurs demandes selon des critères de moralité mais dans le jargon de la sécurité. Ils ne vous demandent pas d’arrêter de leur commenter des livres traitant de questions complexes parce que la pensée exprimée est fausse, mais parce qu’ils les considèrent comme dangereux et ne devraient pas être abordés sans de sévères mises en garde. Ils ne veulent pas faire taire un orateur parce que ses idées sont mauvaises mais parce qu’il représente un danger immédiat pour la communauté universitaire. » Raison unique à cet état de fait : ces étudiants ne tiennent aucun compte des critères de moralité.

Dernière remarque. Le professeur Schwartz relève une observation de l’éditorialiste Megan McArdle. Celle-ci a écrit : « Les étudiants d’aujourd’hui n’expriment pas leurs demandes selon des critères de moralité mais dans le jargon de la sécurité. Ils ne vous demandent pas d’arrêter de leur commenter des livres traitant de questions complexes parce que la pensée exprimée est fausse, mais parce qu’ils les considèrent comme dangereux et ne devraient pas être abordés sans de sévères mises en garde. Ils ne veulent pas faire taire un orateur parce que ses idées sont mauvaises mais parce qu’il représente un danger immédiat pour la communauté universitaire. » Raison unique à cet état de fait : ces étudiants ne tiennent aucun compte des critères de moralité.

I believe it makes sense to start our quest to settle this age-old question by looking at the works of Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804), the German philosopher who is considered the father of modern philosophy. In 1784 he wrote the following about Enlightenment:

I believe it makes sense to start our quest to settle this age-old question by looking at the works of Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804), the German philosopher who is considered the father of modern philosophy. In 1784 he wrote the following about Enlightenment:

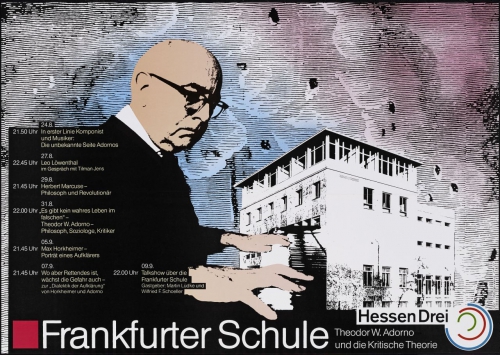

The Frankfurt School claimed that its Critical Theory is the theory of truth. The occidental philosophy, from St. Thomas Aquinas to Kant, as well as Hegel, Fichte, Schelling, and Goethe, should, therefore, be summarily dismissed and replaced by their own dogmatic set of rules and guidelines for “thinking right”. Critical Theory in sociology and political philosophy went beyond interpretation and understanding of society, it sought to overcome and destroy all barriers that, in their view, entrapped society in systems of domination, oppression, and dependency.

The Frankfurt School claimed that its Critical Theory is the theory of truth. The occidental philosophy, from St. Thomas Aquinas to Kant, as well as Hegel, Fichte, Schelling, and Goethe, should, therefore, be summarily dismissed and replaced by their own dogmatic set of rules and guidelines for “thinking right”. Critical Theory in sociology and political philosophy went beyond interpretation and understanding of society, it sought to overcome and destroy all barriers that, in their view, entrapped society in systems of domination, oppression, and dependency.

Mon expérience avec le monde destructeur, absurde et risible de la rectitude politique n’est pas vraiment compréhensible sans que soient mentionnés deux antécédents aux événements: en 1990, j’avais exposé dans la presse et dans un article scientifique que l’Université de Western Ontario, malgré tout ce qu’elle publie sur son excellence dans l’enseignement, accepte des étudiants mentalement arriérés, en langage politiquement correct, des étudiants avec un déficit mental. Comme nous savons tous, les Commissions des droits de l’homme exigent que tous les candidats « qui posent un déficit » doivent être accommodés, ce qui veut dire que les candidats « sous-doués » ont également un droit à une éducation universitaire. C’est aux professeurs à gérer les affaires quand les étudiants ne savent pas écrire à un niveau supérieur de celui de l’école élémentaire. Et cela se passe dans une université à l’admission compétitive (taux d’admission 58%), au niveau très respectable de l’Université de Western Ontario!

Mon expérience avec le monde destructeur, absurde et risible de la rectitude politique n’est pas vraiment compréhensible sans que soient mentionnés deux antécédents aux événements: en 1990, j’avais exposé dans la presse et dans un article scientifique que l’Université de Western Ontario, malgré tout ce qu’elle publie sur son excellence dans l’enseignement, accepte des étudiants mentalement arriérés, en langage politiquement correct, des étudiants avec un déficit mental. Comme nous savons tous, les Commissions des droits de l’homme exigent que tous les candidats « qui posent un déficit » doivent être accommodés, ce qui veut dire que les candidats « sous-doués » ont également un droit à une éducation universitaire. C’est aux professeurs à gérer les affaires quand les étudiants ne savent pas écrire à un niveau supérieur de celui de l’école élémentaire. Et cela se passe dans une université à l’admission compétitive (taux d’admission 58%), au niveau très respectable de l’Université de Western Ontario!

PHILITT :

PHILITT :

Ce philosophe catalan a été défini comme: un "Socrate nordique", un "Goethe méditerranéen", un "personnage de théâtralité baroque".

Ce philosophe catalan a été défini comme: un "Socrate nordique", un "Goethe méditerranéen", un "personnage de théâtralité baroque". Après le philosophe catalan Eugenio d'Ors, abordons la sociologie du Néerlandais Anton Zijderveld (disciple d'Arnold Gehlen).

Après le philosophe catalan Eugenio d'Ors, abordons la sociologie du Néerlandais Anton Zijderveld (disciple d'Arnold Gehlen).

Le corpus le plus significatif, le plus souvent évoqué à l'heure actuelle est l'œuvre de RICHARD RORTY (Contingency, Irony and Solidarity).

Le corpus le plus significatif, le plus souvent évoqué à l'heure actuelle est l'œuvre de RICHARD RORTY (Contingency, Irony and Solidarity).  Rabelais (1494-1553), pourquoi Rabelais?

Rabelais (1494-1553), pourquoi Rabelais? Bakhtine en mettant en parallèle son réalisme grotesque et le réalisme socialiste officiel, revalorisera “LE PEUPLE RIANT SUR LA PLACE DU MARCHÉ”.

Bakhtine en mettant en parallèle son réalisme grotesque et le réalisme socialiste officiel, revalorisera “LE PEUPLE RIANT SUR LA PLACE DU MARCHÉ”.  Nietzsche voit dans le corps le site d'une complexité née de multiples et diverses intersubjectivités et interactions, le lieu de passage de l'expérience, toujours diverse, chaque fois unique.

Nietzsche voit dans le corps le site d'une complexité née de multiples et diverses intersubjectivités et interactions, le lieu de passage de l'expérience, toujours diverse, chaque fois unique.  In the heady days immediately after the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, it was widely believed that proletarian revolution would momentarily sweep out of the Urals into Europe and, ultimately, North America. It did not; the only two attempts at workers' government in the West— in Munich and Budapest—lasted only months. The Communist International (Comintern) therefore began several operations to determine why this was so. One such was headed by Georg Lukacs, a Hungarian aristocrat, son of one of the Hapsburg Empire's leading bankers. Trained in Germany and already an important literary theorist, Lukacs became a Communist during World War I, writing as he joined the party, "Who will save us from Western civilization?" Lukacs was well-suited to the Comintern task: he had been one of the Commissars of Culture during the short-lived Hungarian Soviet in Budapest in 1919; in fact, modern historians link the shortness of the Budapest experiment to Lukacs' orders mandating sex education in the schools, easy access to contraception, and the loosening of divorce laws—all of which revulsed Hungary's Roman Catholic population.

In the heady days immediately after the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, it was widely believed that proletarian revolution would momentarily sweep out of the Urals into Europe and, ultimately, North America. It did not; the only two attempts at workers' government in the West— in Munich and Budapest—lasted only months. The Communist International (Comintern) therefore began several operations to determine why this was so. One such was headed by Georg Lukacs, a Hungarian aristocrat, son of one of the Hapsburg Empire's leading bankers. Trained in Germany and already an important literary theorist, Lukacs became a Communist during World War I, writing as he joined the party, "Who will save us from Western civilization?" Lukacs was well-suited to the Comintern task: he had been one of the Commissars of Culture during the short-lived Hungarian Soviet in Budapest in 1919; in fact, modern historians link the shortness of the Budapest experiment to Lukacs' orders mandating sex education in the schools, easy access to contraception, and the loosening of divorce laws—all of which revulsed Hungary's Roman Catholic population. Lukacs survived to briefly take up his old post as Minister of Culture during the anti-Stalinist Imre Nagy regime in Hungary. Of the other top Institute figures, the political perambulations of Herbert Marcuse are typical. He started as a Communist; became a protégé of philosopher Martin Heidegger even as the latter was joining the Nazi Party; coming to America, he worked for the World War II Office of Strategic Services (OSS), and later became the U.S. State Department's top analyst of Soviet policy during the height of the McCarthy period; in the 1960's, he turned again, to become the most important guru of the New Left; and he ended his days helping to found the environmentalist extremist Green Party in West Germany.

Lukacs survived to briefly take up his old post as Minister of Culture during the anti-Stalinist Imre Nagy regime in Hungary. Of the other top Institute figures, the political perambulations of Herbert Marcuse are typical. He started as a Communist; became a protégé of philosopher Martin Heidegger even as the latter was joining the Nazi Party; coming to America, he worked for the World War II Office of Strategic Services (OSS), and later became the U.S. State Department's top analyst of Soviet policy during the height of the McCarthy period; in the 1960's, he turned again, to become the most important guru of the New Left; and he ended his days helping to found the environmentalist extremist Green Party in West Germany. Perhaps the most important, if least-known, of the Frankfurt School's successes was the shaping of the electronic media of radio and television into the powerful instruments of social control which they represent today. This grew out of the work originally done by two men who came to the Institute in the late 1920's, Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin.

Perhaps the most important, if least-known, of the Frankfurt School's successes was the shaping of the electronic media of radio and television into the powerful instruments of social control which they represent today. This grew out of the work originally done by two men who came to the Institute in the late 1920's, Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin. From 1928 to 1932, Adorno and Benjamin had an intensive collaboration, at the end of which they began publishing articles in the Institute's journal, the Zeitschrift fär Sozialforschung. Benjamin was kept on the margins of the Institute, largely due to Adorno, who would later appropriate much of his work. As Hitler came to power, the Institute's staff fled, but, whereas most were quickly spirited away to new deployments in the U.S. and England, there were no job offers for Benjamin, probably due to the animus of Adorno. He went to France, and, after the German invasion, fled to the Spanish border; expecting momentary arrest by the Gestapo, he despaired and died in a dingy hotel room of self-administered drug overdose.

From 1928 to 1932, Adorno and Benjamin had an intensive collaboration, at the end of which they began publishing articles in the Institute's journal, the Zeitschrift fär Sozialforschung. Benjamin was kept on the margins of the Institute, largely due to Adorno, who would later appropriate much of his work. As Hitler came to power, the Institute's staff fled, but, whereas most were quickly spirited away to new deployments in the U.S. and England, there were no job offers for Benjamin, probably due to the animus of Adorno. He went to France, and, after the German invasion, fled to the Spanish border; expecting momentary arrest by the Gestapo, he despaired and died in a dingy hotel room of self-administered drug overdose. Adorno was younger than Benjamin, and as aggressive as the older man was passive. Born Teodoro Wiesengrund-Adorno to a Corsican family, he was taught the piano at an early age by an aunt who lived with the family and had been the concert accompanist to the international opera star Adelina Patti. It was generally thought that Theodor would become a professional musician, and he studied with Bernard Sekles, Paul Hindemith's teacher. However, in 1918, while still a gymnasium student, Adorno met Siegfried Kracauer. Kracauer was part of a Kantian-Zionist salon which met at the house of Rabbi Nehemiah Nobel in Frankfurt; other members of the Nobel circle included philosopher Martin Buber, writer Franz Rosenzweig, and two students, Leo Lowenthal and Erich Fromm. Kracauer, Lowenthal, and Fromm would join the I.S.R. two decades later. Adorno engaged Kracauer to tutor him in the philosophy of Kant; Kracauer also introduced him to the writings of Lukacs and to Walter Benjamin, who was around the Nobel clique.

Adorno was younger than Benjamin, and as aggressive as the older man was passive. Born Teodoro Wiesengrund-Adorno to a Corsican family, he was taught the piano at an early age by an aunt who lived with the family and had been the concert accompanist to the international opera star Adelina Patti. It was generally thought that Theodor would become a professional musician, and he studied with Bernard Sekles, Paul Hindemith's teacher. However, in 1918, while still a gymnasium student, Adorno met Siegfried Kracauer. Kracauer was part of a Kantian-Zionist salon which met at the house of Rabbi Nehemiah Nobel in Frankfurt; other members of the Nobel circle included philosopher Martin Buber, writer Franz Rosenzweig, and two students, Leo Lowenthal and Erich Fromm. Kracauer, Lowenthal, and Fromm would join the I.S.R. two decades later. Adorno engaged Kracauer to tutor him in the philosophy of Kant; Kracauer also introduced him to the writings of Lukacs and to Walter Benjamin, who was around the Nobel clique. In 1924, Adorno moved to Vienna, to study with the atonalist composers Alban Berg and Arnold Schönberg, and became connected to the avant-garde and occult circle around the old Marxist Karl Kraus. Here, he not only met his future collaborator, Hans Eisler, but also came into contact with the theories of Freudian extremist Otto Gross. Gross, a long-time cocaine addict, had died in a Berlin gutter in 1920, while on his way to help the revolution in Budapest; he had developed the theory that mental health could only be achieved through the revival of the ancient cult of Astarte, which would sweep away monotheism and the "bourgeois family."

In 1924, Adorno moved to Vienna, to study with the atonalist composers Alban Berg and Arnold Schönberg, and became connected to the avant-garde and occult circle around the old Marxist Karl Kraus. Here, he not only met his future collaborator, Hans Eisler, but also came into contact with the theories of Freudian extremist Otto Gross. Gross, a long-time cocaine addict, had died in a Berlin gutter in 1920, while on his way to help the revolution in Budapest; he had developed the theory that mental health could only be achieved through the revival of the ancient cult of Astarte, which would sweep away monotheism and the "bourgeois family." The Adorno-Benjamin analysis represents almost the entire theoretical basis of all the politically correct aesthetic trends which now plague our universities. The Poststructuralism of Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Derrida, the Semiotics of Umberto Eco, the Deconstructionism of Paul DeMan, all openly cite Benjamin as the source of their work. The Italian terrorist Eco's best-selling novel, The Name of the Rose, is little more than a paean to Benjamin; DeMan, the former Nazi collaborator in Belgium who became a prestigious Yale professor, began his career translating Benjamin; Barthes' infamous 1968 statement that "[t]he author is dead," is meant as an elaboration of Benjamin's dictum on intention. Benjamin has actually been called the heir of Leibniz and of Wilhelm von Humboldt, the philologist collaborator of Schiller whose educational reforms engendered the tremendous development of Germany in the nineteenth century. Even as recently as September 1991, the Washington Post referred to Benjamin as "the finest German literary theorist of the century (and many would have left off that qualifying German)."

The Adorno-Benjamin analysis represents almost the entire theoretical basis of all the politically correct aesthetic trends which now plague our universities. The Poststructuralism of Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Derrida, the Semiotics of Umberto Eco, the Deconstructionism of Paul DeMan, all openly cite Benjamin as the source of their work. The Italian terrorist Eco's best-selling novel, The Name of the Rose, is little more than a paean to Benjamin; DeMan, the former Nazi collaborator in Belgium who became a prestigious Yale professor, began his career translating Benjamin; Barthes' infamous 1968 statement that "[t]he author is dead," is meant as an elaboration of Benjamin's dictum on intention. Benjamin has actually been called the heir of Leibniz and of Wilhelm von Humboldt, the philologist collaborator of Schiller whose educational reforms engendered the tremendous development of Germany in the nineteenth century. Even as recently as September 1991, the Washington Post referred to Benjamin as "the finest German literary theorist of the century (and many would have left off that qualifying German)." The director of the Project was Paul Lazersfeld, the foster son of Austrian Marxist economist Rudolph Hilferding, and a long-time collaborator of the I.S.R. from the early 1930's. Under Lazersfeld was Frank Stanton, a recent Ph.D. in industrial psychology from Ohio State, who had just been made research director of Columbia Broadcasting System—a grand title but a lowly position. After World War II, Stanton became president of the CBS News Division, and ultimately president of CBS at the height of the TV network's power; he also became Chairman of the Board of the RAND Corporation, and a member of President Lyndon Johnson's "kitchen cabinet." Among the Project's researchers were Herta Herzog, who married Lazersfeld and became the first director of research for the Voice of America; and Hazel Gaudet, who became one of the nation's leading political pollsters. Theodor Adorno was named chief of the Project's music section.

The director of the Project was Paul Lazersfeld, the foster son of Austrian Marxist economist Rudolph Hilferding, and a long-time collaborator of the I.S.R. from the early 1930's. Under Lazersfeld was Frank Stanton, a recent Ph.D. in industrial psychology from Ohio State, who had just been made research director of Columbia Broadcasting System—a grand title but a lowly position. After World War II, Stanton became president of the CBS News Division, and ultimately president of CBS at the height of the TV network's power; he also became Chairman of the Board of the RAND Corporation, and a member of President Lyndon Johnson's "kitchen cabinet." Among the Project's researchers were Herta Herzog, who married Lazersfeld and became the first director of research for the Voice of America; and Hazel Gaudet, who became one of the nation's leading political pollsters. Theodor Adorno was named chief of the Project's music section. The first studies were promising. Herta Herzog produced "On Borrowed Experiences," the first comprehensive research on soap operas. The "serial radio drama" format was first used in 1929, on the inspiration of the old, cliff-hanger "Perils of Pauline" film serial. Because these little radio plays were highly melodramatic, they became popularly identified with Italian grand opera; because they were often sponsored by soap manufacturers, they ended up with the generic name, "soap opera."

The first studies were promising. Herta Herzog produced "On Borrowed Experiences," the first comprehensive research on soap operas. The "serial radio drama" format was first used in 1929, on the inspiration of the old, cliff-hanger "Perils of Pauline" film serial. Because these little radio plays were highly melodramatic, they became popularly identified with Italian grand opera; because they were often sponsored by soap manufacturers, they ended up with the generic name, "soap opera." These psychoanalytic survey techniques became standard, not only for the Frankfurt School, but also throughout American social science departments, particularly after the I.S.R. arrived in the United States. The methodology was the basis of the research piece for which the Frankfurt School is most well known, the "authoritarian personality" project. In 1942, I.S.R. director Max Horkheimer made contact with the American Jewish Committee, which asked him to set up a Department of Scientific Research within its organization. The American Jewish Committee also provided a large grant to study anti-Semitism in the American population. "Our aim," wrote Horkheimer in the introduction to the study, "is not merely to describe prejudice, but to explain it in order to help in its eradication.... Eradication means reeducation scientifically planned on the basis of understanding scientifically arrived at."

These psychoanalytic survey techniques became standard, not only for the Frankfurt School, but also throughout American social science departments, particularly after the I.S.R. arrived in the United States. The methodology was the basis of the research piece for which the Frankfurt School is most well known, the "authoritarian personality" project. In 1942, I.S.R. director Max Horkheimer made contact with the American Jewish Committee, which asked him to set up a Department of Scientific Research within its organization. The American Jewish Committee also provided a large grant to study anti-Semitism in the American population. "Our aim," wrote Horkheimer in the introduction to the study, "is not merely to describe prejudice, but to explain it in order to help in its eradication.... Eradication means reeducation scientifically planned on the basis of understanding scientifically arrived at." Ultimately, five volumes were produced for this study over the course of the late 1940's; the most important was the last, The Authoritarian Personality, by Adorno, with the help of three Berkeley, California social psychologists.

Ultimately, five volumes were produced for this study over the course of the late 1940's; the most important was the last, The Authoritarian Personality, by Adorno, with the help of three Berkeley, California social psychologists. This self-serving attempt to maximize paranoia was further aided by Hannah Arendt, who popularized the authoritarian personality research in her widely-read Origins of Totalitarianism. Arendt also added the famous rhetorical flourish about the "banality of evil" in her later Eichmann in Jerusalem: even a simple, shopkeeper-type like Eichmann can turn into a Nazi beast under the right psychological circumstances—every Gentile is suspect, psychoanalytically.

This self-serving attempt to maximize paranoia was further aided by Hannah Arendt, who popularized the authoritarian personality research in her widely-read Origins of Totalitarianism. Arendt also added the famous rhetorical flourish about the "banality of evil" in her later Eichmann in Jerusalem: even a simple, shopkeeper-type like Eichmann can turn into a Nazi beast under the right psychological circumstances—every Gentile is suspect, psychoanalytically. Part of the influence of the authoritarian personality hoax in our own day also derives from the fact that, incredibly, the Frankfurt School and its theories were officially accepted by the U.S. government during World War II, and these Cominternists were responsible for determining who were America's wartime, and postwar, enemies. In 1942, the Office of Strategic Services, America's hastily-constructed espionage and covert operations unit, asked former Harvard president James Baxter to form a Research and Analysis (R&A) Branch under the group's Intelligence Division. By 1944, the R&A Branch had collected such a large and prestigeous group of emigré scholars that H. Stuart Hughes, then a young Ph.D., said that working for it was "a second graduate education" at government expense. The Central European Section was headed by historian Carl Schorske; under him, in the all-important Germany/Austria Section, was Franz Neumann, as section chief, with Herbert Marcuse, Paul Baran, and Otto Kirchheimer, all I.S.R. veterans. Leo Lowenthal headed the German-language section of the Office of War Information; Sophie Marcuse, Marcuse's wife, worked at the Office of Naval Intelligence. Also at the R&A Branch were: Siegfried Kracauer, Adorno's old Kant instructor, now a film theorist; Norman O. Brown, who would become famous in the 1960's by combining Marcuse's hedonism theory with Wilhelm Reich's orgone therapy to popularize "polymorphous perversity"; Barrington Moore, Jr., later a philosophy professor who would co-author a book with Marcuse; Gregory Bateson, the husband of anthropologist Margaret Mead (who wrote for the Frankfurt School's journal), and Arthur Schlesinger, the historian who joined the Kennedy Administration. Marcuse's first assignment was to head a team to identify both those who would be tried as war criminals after the war, and also those who were potential leaders of postwar Germany. In 1944, Marcuse, Neumann, and Kirchheimer wrote the Denazification Guide, which was later issued to officers of the U.S. Armed Forces occupying Germany, to help them identify and suppress pro-Nazi behaviors. After the armistice, the R&A Branch sent representatives to work as intelligence liaisons with the various occupying powers; Marcuse was assigned the U.S. Zone, Kirchheimer the French, and Barrington Moore the Soviet. In the summer of 1945, Neumann left to become chief of research for the Nuremburg Tribunal. Marcuse remained in and around U.S. intelligence into the early 1950's, rising to the chief of the Central European Branch of the State Department's Office of Intelligence Research, an office formally charged with "planning and implementing a program of positive-intelligence research ... to meet the intelligence requirements of the Central Intelligence Agency and other authorized agencies." During his tenure as a U.S. government official, Marcuse supported the division of Germany into East and West, noting that this would prevent an alliance between the newly liberated left-wing parties and the old, conservative industrial and business layers. In 1949, he produced a 532-page report, "The Potentials of World Communism" (declassified only in 1978), which suggested that the Marshall Plan economic stabilization of Europe would limit the recruitment potential of Western Europe's Communist Parties to acceptable levels, causing a period of hostile co-existence with the Soviet Union, marked by confrontation only in faraway places like Latin America and Indochina—in all, a surprisingly accurate forecast. Marcuse left the State Department with a Rockefeller Foundation grant to work with the various Soviet Studies departments which were set up at many of America's top universities after the war, largely by R&A Branch veterans.

Part of the influence of the authoritarian personality hoax in our own day also derives from the fact that, incredibly, the Frankfurt School and its theories were officially accepted by the U.S. government during World War II, and these Cominternists were responsible for determining who were America's wartime, and postwar, enemies. In 1942, the Office of Strategic Services, America's hastily-constructed espionage and covert operations unit, asked former Harvard president James Baxter to form a Research and Analysis (R&A) Branch under the group's Intelligence Division. By 1944, the R&A Branch had collected such a large and prestigeous group of emigré scholars that H. Stuart Hughes, then a young Ph.D., said that working for it was "a second graduate education" at government expense. The Central European Section was headed by historian Carl Schorske; under him, in the all-important Germany/Austria Section, was Franz Neumann, as section chief, with Herbert Marcuse, Paul Baran, and Otto Kirchheimer, all I.S.R. veterans. Leo Lowenthal headed the German-language section of the Office of War Information; Sophie Marcuse, Marcuse's wife, worked at the Office of Naval Intelligence. Also at the R&A Branch were: Siegfried Kracauer, Adorno's old Kant instructor, now a film theorist; Norman O. Brown, who would become famous in the 1960's by combining Marcuse's hedonism theory with Wilhelm Reich's orgone therapy to popularize "polymorphous perversity"; Barrington Moore, Jr., later a philosophy professor who would co-author a book with Marcuse; Gregory Bateson, the husband of anthropologist Margaret Mead (who wrote for the Frankfurt School's journal), and Arthur Schlesinger, the historian who joined the Kennedy Administration. Marcuse's first assignment was to head a team to identify both those who would be tried as war criminals after the war, and also those who were potential leaders of postwar Germany. In 1944, Marcuse, Neumann, and Kirchheimer wrote the Denazification Guide, which was later issued to officers of the U.S. Armed Forces occupying Germany, to help them identify and suppress pro-Nazi behaviors. After the armistice, the R&A Branch sent representatives to work as intelligence liaisons with the various occupying powers; Marcuse was assigned the U.S. Zone, Kirchheimer the French, and Barrington Moore the Soviet. In the summer of 1945, Neumann left to become chief of research for the Nuremburg Tribunal. Marcuse remained in and around U.S. intelligence into the early 1950's, rising to the chief of the Central European Branch of the State Department's Office of Intelligence Research, an office formally charged with "planning and implementing a program of positive-intelligence research ... to meet the intelligence requirements of the Central Intelligence Agency and other authorized agencies." During his tenure as a U.S. government official, Marcuse supported the division of Germany into East and West, noting that this would prevent an alliance between the newly liberated left-wing parties and the old, conservative industrial and business layers. In 1949, he produced a 532-page report, "The Potentials of World Communism" (declassified only in 1978), which suggested that the Marshall Plan economic stabilization of Europe would limit the recruitment potential of Western Europe's Communist Parties to acceptable levels, causing a period of hostile co-existence with the Soviet Union, marked by confrontation only in faraway places like Latin America and Indochina—in all, a surprisingly accurate forecast. Marcuse left the State Department with a Rockefeller Foundation grant to work with the various Soviet Studies departments which were set up at many of America's top universities after the war, largely by R&A Branch veterans. At the same time, Max Horkheimer was doing even greater damage. As part of the denazification of Germany suggested by the R&A Branch, U.S. High Commissioner for Germany John J. McCloy, using personal discretionary funds, brought Horkheimer back to Germany to reform the German university system. In fact, McCloy asked President Truman and Congress to pass a bill granting Horkheimer, who had become a naturalized American, dual citizenship; thus, for a brief period, Horkheimer was the only person in the world to hold both German and U.S. citizenship. In Germany, Horkheimer began the spadework for the full-blown revival of the Frankfurt School in that nation in the late 1950's, including the training of a whole new generation of anti-Western civilization scholars like Hans-Georg Gadamer and Jürgen Habermas, who would have such destructive influence in 1960's Germany. In a period of American history when some individuals were being hounded into unemployment and suicide for the faintest aroma of leftism, Frankfurt School veterans—all with superb Comintern credentials — led what can only be called charmed lives. America had, to an incredible extent, handed the determination of who were the nation's enemies, over to the nation's own worst enemies.

At the same time, Max Horkheimer was doing even greater damage. As part of the denazification of Germany suggested by the R&A Branch, U.S. High Commissioner for Germany John J. McCloy, using personal discretionary funds, brought Horkheimer back to Germany to reform the German university system. In fact, McCloy asked President Truman and Congress to pass a bill granting Horkheimer, who had become a naturalized American, dual citizenship; thus, for a brief period, Horkheimer was the only person in the world to hold both German and U.S. citizenship. In Germany, Horkheimer began the spadework for the full-blown revival of the Frankfurt School in that nation in the late 1950's, including the training of a whole new generation of anti-Western civilization scholars like Hans-Georg Gadamer and Jürgen Habermas, who would have such destructive influence in 1960's Germany. In a period of American history when some individuals were being hounded into unemployment and suicide for the faintest aroma of leftism, Frankfurt School veterans—all with superb Comintern credentials — led what can only be called charmed lives. America had, to an incredible extent, handed the determination of who were the nation's enemies, over to the nation's own worst enemies. The simmering unrest on campus in 1960 might well too have passed or had a positive outcome, were it not for the traumatic decapitation of the nation through the Kennedy assassination, plus the simultaneous introduction of widespread drug use. Drugs had always been an "analytical tool" of the nineteenth century Romantics, like the French Symbolists, and were popular among the European and American Bohemian fringe well into the post-World War II period. But, in the second half of the 1950's, the CIA and allied intelligence services began extensive experimentation with the hallucinogen LSD to investigate its potential for social control. It has now been documented that millions of doses of the chemical were produced and disseminated under the aegis of the CIA's Operation MK-Ultra. LSD became the drug of choice within the agency itself, and was passed out freely to friends of the family, including a substantial number of OSS veterans. For instance, it was OSS Research and Analysis Branch veteran Gregory Bateson who "turned on" the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg to a U.S. Navy LSD experiment in Palo Alto, California. Not only Ginsberg, but novelist Ken Kesey and the original members of the Grateful Dead rock group opened the doors of perception courtesy of the Navy. The guru of the "psychedelic revolution," Timothy Leary, first heard about hallucinogens in 1957 from Life magazine (whose publisher, Henry Luce, was often given government acid, like many other opinion shapers), and began his career as a CIA contract employee; at a 1977 "reunion" of acid pioneers, Leary openly admitted, "everything I am, I owe to the foresight of the CIA." Hallucinogens have the singular effect of making the victim asocial, totally self-centered, and concerned with objects. Even the most banal objects take on the "aura" which Benjamin had talked about, and become timeless and delusionarily profound. In other words, hallucinogens instantaneously achieve a state of mind identical to that prescribed by the Frankfurt School theories. And, the popularization of these chemicals created a vast psychological lability for bringing those theories into practice. Thus, the situation at the beginning of the 1960's represented a brilliant re-entry point for the Frankfurt School, and it was fully exploited. One of the crowning ironies of the "Now Generation" of 1964 on, is that, for all its protestations of utter modernity, none of its ideas or artifacts was less than thirty years old. The political theory came completely from the Frankfurt School; Lucien Goldmann, a French radical who was a visiting professor at Columbia in 1968, was absolutely correct when he said of Herbert Marcuse in 1969 that "the student movements ... found in his works and ultimately in his works alone the theoretical formulation of their problems and aspirations [emphasis in original]." The long hair and sandals, the free love communes, the macrobiotic food, the liberated lifestyles, had been designed at the turn of the century, and thoroughly field-tested by various, Frankfurt School-connected New Age social experiments like the Ascona commune before 1920. (See box.) Even Tom Hayden's defiant "Never trust anyone over thirty," was merely a less-urbane version of Rupert Brooke's 1905, "Nobody over thirty is worth talking to." The social planners who shaped the 1960's simply relied on already-available materials.

The simmering unrest on campus in 1960 might well too have passed or had a positive outcome, were it not for the traumatic decapitation of the nation through the Kennedy assassination, plus the simultaneous introduction of widespread drug use. Drugs had always been an "analytical tool" of the nineteenth century Romantics, like the French Symbolists, and were popular among the European and American Bohemian fringe well into the post-World War II period. But, in the second half of the 1950's, the CIA and allied intelligence services began extensive experimentation with the hallucinogen LSD to investigate its potential for social control. It has now been documented that millions of doses of the chemical were produced and disseminated under the aegis of the CIA's Operation MK-Ultra. LSD became the drug of choice within the agency itself, and was passed out freely to friends of the family, including a substantial number of OSS veterans. For instance, it was OSS Research and Analysis Branch veteran Gregory Bateson who "turned on" the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg to a U.S. Navy LSD experiment in Palo Alto, California. Not only Ginsberg, but novelist Ken Kesey and the original members of the Grateful Dead rock group opened the doors of perception courtesy of the Navy. The guru of the "psychedelic revolution," Timothy Leary, first heard about hallucinogens in 1957 from Life magazine (whose publisher, Henry Luce, was often given government acid, like many other opinion shapers), and began his career as a CIA contract employee; at a 1977 "reunion" of acid pioneers, Leary openly admitted, "everything I am, I owe to the foresight of the CIA." Hallucinogens have the singular effect of making the victim asocial, totally self-centered, and concerned with objects. Even the most banal objects take on the "aura" which Benjamin had talked about, and become timeless and delusionarily profound. In other words, hallucinogens instantaneously achieve a state of mind identical to that prescribed by the Frankfurt School theories. And, the popularization of these chemicals created a vast psychological lability for bringing those theories into practice. Thus, the situation at the beginning of the 1960's represented a brilliant re-entry point for the Frankfurt School, and it was fully exploited. One of the crowning ironies of the "Now Generation" of 1964 on, is that, for all its protestations of utter modernity, none of its ideas or artifacts was less than thirty years old. The political theory came completely from the Frankfurt School; Lucien Goldmann, a French radical who was a visiting professor at Columbia in 1968, was absolutely correct when he said of Herbert Marcuse in 1969 that "the student movements ... found in his works and ultimately in his works alone the theoretical formulation of their problems and aspirations [emphasis in original]." The long hair and sandals, the free love communes, the macrobiotic food, the liberated lifestyles, had been designed at the turn of the century, and thoroughly field-tested by various, Frankfurt School-connected New Age social experiments like the Ascona commune before 1920. (See box.) Even Tom Hayden's defiant "Never trust anyone over thirty," was merely a less-urbane version of Rupert Brooke's 1905, "Nobody over thirty is worth talking to." The social planners who shaped the 1960's simply relied on already-available materials. This erotic liberation should take the form of the "Great Refusal," a total rejection of the "capitalist" monster and all his works, including "technological" reason, and "ritual-authoritarian language." As part of the Great Refusal, mankind should develop an "aesthetic ethos," turning life into an aesthetic ritual, a "life-style" (a nonsense phrase which came into the language in the 1960's under Marcuse's influence). With Marcuse representing the point of the wedge, the 1960's were filled with obtuse intellectual justifications of contentless adolescent sexual rebellion. Eros and Civilization was reissued as an inexpensive paperback in 1961, and ran through several editions; in the preface to the 1966 edition, Marcuse added that the new slogan, "Make Love, Not War," was exactly what he was talking about: "The fight for eros is a political fight [emphasis in original]." In 1969, he noted that even the New Left's obsessive use of obscenities in its manifestoes was part of the Great Refusal, calling it "a systematic linguistic rebellion, which smashes the ideological context in which the words are employed and defined." Marcuse was aided by psychoanalyst Norman O. Brown, his OSS protege, who contributed Life Against Death in 1959, and Love's Body in 1966—calling for man to shed his reasonable, "armored" ego, and replace it with a "Dionysian body ego," that would embrace the instinctual reality of polymorphous perversity, and bring man back into "union with nature." The books of Reich, who had claimed that Nazism was caused by monogamy, were re-issued. Reich had died in an American prison, jailed for taking money on the claim that cancer could be cured by rechanneling "orgone energy." Primary education became dominated by Reich's leading follower, A.S. Neill, a Theosophical cult member of the 1930's and militant atheist, whose educational theories demanded that students be taught to rebel against teachers who are, by nature, authoritarian. Neill's book Summerhill sold 24,000 copies in 1960, rising to 100,000 in 1968, and 2 million in 1970; by 1970, it was required reading in 600 university courses, making it one of the most influential education texts of the period, and still a benchmark for recent writers on the subject. Marcuse led the way for the complete revival of the rest of the Frankfurt School theorists, re-introducing the long-forgotten Lukacs to America. Marcuse himself became the lightning rod for attacks on the counterculture, and was regularly attacked by such sources as the Soviet daily Pravda, and then-California Governor Ronald Reagan. The only critique of any merit at the time, however, was one by Pope Paul VI, who in 1969 named Marcuse (an extraordinary step, as the Vatican usually refrains from formal denunciations of living individuals), along with Freud, for their justification of "disgusting and unbridled expressions of eroticism"; and called Marcuse's theory of liberation, "the theory which opens the way for license cloaked as liberty ... an aberration of instinct." The eroticism of the counterculture meant much more than free love and a violent attack on the nuclear family. It also meant the legitimization of philosophical eros. People were trained to see themselves as objects, determined by their "natures." The importance of the individual as a person gifted with the divine spark of creativity, and capable of acting upon all human civilization, was replaced by the idea that the person is important because he or she is black, or a woman, or feels homosexual impulses. This explains the deformation of the civil rights movement into a "black power" movement, and the transformation of the legitimate issue of civil rights for women into feminism. Discussion of women's civil rights was forced into being just another "liberation cult," complete with bra-burning and other, sometimes openly Astarte-style, rituals; a review of Kate Millet's Sexual Politics (1970) and Germaine Greer's The Female Eunuch (1971), demonstrates their complete reliance on Marcuse, Fromm, Reich, and other Freudian extremists.

This erotic liberation should take the form of the "Great Refusal," a total rejection of the "capitalist" monster and all his works, including "technological" reason, and "ritual-authoritarian language." As part of the Great Refusal, mankind should develop an "aesthetic ethos," turning life into an aesthetic ritual, a "life-style" (a nonsense phrase which came into the language in the 1960's under Marcuse's influence). With Marcuse representing the point of the wedge, the 1960's were filled with obtuse intellectual justifications of contentless adolescent sexual rebellion. Eros and Civilization was reissued as an inexpensive paperback in 1961, and ran through several editions; in the preface to the 1966 edition, Marcuse added that the new slogan, "Make Love, Not War," was exactly what he was talking about: "The fight for eros is a political fight [emphasis in original]." In 1969, he noted that even the New Left's obsessive use of obscenities in its manifestoes was part of the Great Refusal, calling it "a systematic linguistic rebellion, which smashes the ideological context in which the words are employed and defined." Marcuse was aided by psychoanalyst Norman O. Brown, his OSS protege, who contributed Life Against Death in 1959, and Love's Body in 1966—calling for man to shed his reasonable, "armored" ego, and replace it with a "Dionysian body ego," that would embrace the instinctual reality of polymorphous perversity, and bring man back into "union with nature." The books of Reich, who had claimed that Nazism was caused by monogamy, were re-issued. Reich had died in an American prison, jailed for taking money on the claim that cancer could be cured by rechanneling "orgone energy." Primary education became dominated by Reich's leading follower, A.S. Neill, a Theosophical cult member of the 1930's and militant atheist, whose educational theories demanded that students be taught to rebel against teachers who are, by nature, authoritarian. Neill's book Summerhill sold 24,000 copies in 1960, rising to 100,000 in 1968, and 2 million in 1970; by 1970, it was required reading in 600 university courses, making it one of the most influential education texts of the period, and still a benchmark for recent writers on the subject. Marcuse led the way for the complete revival of the rest of the Frankfurt School theorists, re-introducing the long-forgotten Lukacs to America. Marcuse himself became the lightning rod for attacks on the counterculture, and was regularly attacked by such sources as the Soviet daily Pravda, and then-California Governor Ronald Reagan. The only critique of any merit at the time, however, was one by Pope Paul VI, who in 1969 named Marcuse (an extraordinary step, as the Vatican usually refrains from formal denunciations of living individuals), along with Freud, for their justification of "disgusting and unbridled expressions of eroticism"; and called Marcuse's theory of liberation, "the theory which opens the way for license cloaked as liberty ... an aberration of instinct." The eroticism of the counterculture meant much more than free love and a violent attack on the nuclear family. It also meant the legitimization of philosophical eros. People were trained to see themselves as objects, determined by their "natures." The importance of the individual as a person gifted with the divine spark of creativity, and capable of acting upon all human civilization, was replaced by the idea that the person is important because he or she is black, or a woman, or feels homosexual impulses. This explains the deformation of the civil rights movement into a "black power" movement, and the transformation of the legitimate issue of civil rights for women into feminism. Discussion of women's civil rights was forced into being just another "liberation cult," complete with bra-burning and other, sometimes openly Astarte-style, rituals; a review of Kate Millet's Sexual Politics (1970) and Germaine Greer's The Female Eunuch (1971), demonstrates their complete reliance on Marcuse, Fromm, Reich, and other Freudian extremists.

Archives de Synergies Européennes - 1998

Archives de Synergies Européennes - 1998

On nous reproche souvent de ne relever que les mauvaises choses de notre époque et de privilégier nos indignations à nos émerveillements. C’est l’inverse que je vous propose aujourd’hui en vous recommandant par ces temps de crise pas seulement financière de vous payer un tour de Gran Torino. Si vous voulez oublier Lol et autres Cyprien pour voir le meilleur film de ces dix dernières années et donc – pour le moment – du XXIe siècle, foncez sur le dernier Clint Eastwood : il a dégainé son chef-d‘œuvre.

On nous reproche souvent de ne relever que les mauvaises choses de notre époque et de privilégier nos indignations à nos émerveillements. C’est l’inverse que je vous propose aujourd’hui en vous recommandant par ces temps de crise pas seulement financière de vous payer un tour de Gran Torino. Si vous voulez oublier Lol et autres Cyprien pour voir le meilleur film de ces dix dernières années et donc – pour le moment – du XXIe siècle, foncez sur le dernier Clint Eastwood : il a dégainé son chef-d‘œuvre.