mardi, 04 novembre 2014

Chachapoya of Peru Are Probably Carthaginians and Celts Who Fled from Rome in 146 BCE

PBS: Chachapoya of Peru Are Probably Carthaginians and Celts Who Fled from Rome in 146 BCE

Holy crap! PBS has become America Unearthed. In an episode of the PBS series Secrets of the Dead running on local PBS stations this week and available online for streaming, the venerable public broadcasting channel asserts that blonde-haired, blue-eyed Celts and also some incidental Carthaginians discovered the Americas in Antiquity. (The blue eyes don’t make the show but show up on the show’s web page.) “Carthage’s Lost Warriors” was produced by ZDF, a German television production company associated with the long-running series Terra-X, which traffics in all manner of fringe theories, and the large number of dubbed German interviews testifies to the recycling of a German program. Archaeologist K. Krist Hurst called the show “baloney.”

Holy crap! PBS has become America Unearthed. In an episode of the PBS series Secrets of the Dead running on local PBS stations this week and available online for streaming, the venerable public broadcasting channel asserts that blonde-haired, blue-eyed Celts and also some incidental Carthaginians discovered the Americas in Antiquity. (The blue eyes don’t make the show but show up on the show’s web page.) “Carthage’s Lost Warriors” was produced by ZDF, a German television production company associated with the long-running series Terra-X, which traffics in all manner of fringe theories, and the large number of dubbed German interviews testifies to the recycling of a German program. Archaeologist K. Krist Hurst called the show “baloney.”The program is based on the work of the show’s chief expert, Hans Giffhorn, a professor emeritus of cultural studies at the Universities of Göttingen and Hildesheim and documentary filmmaker. Griffhorn’s dissertation on aesthetics outlined his belief that science is dogmatic and rigid and excludes evidence and theories that fail to conform to paradigms, and that a lack of cross-disciplinary interaction has led to erroneous findings and conclusions.

Griffhorn wrote a German book, still untranslated, on his belief that the Chachapoya are white Europeans in 2013.He believes that the Carthaginians did not “simply vanish” after the Carthaginians were defeated by the Romans in 146 BCE, and he refuses to believe Roman accounts that the city’s population was enslaved or killed under Scipio Aemilianus. He wants to know where they went. To find the Carthaginians—and here he is looking for just one boatload—he starts at the Balearic Islands, where Carthage found its fiercest soldiers. Giffhorn feels that the Carthaginians were not enslaved in their entirety, so for him it is only logical that they fled to Kuelap, the Chachapoya fortress in Peru. He believes that in the western Mediterranean the Carthaginian exiles teamed up with Celtic people from Iberia to escape the Romans, who were also taking over the Carthaginian territories of what is today Spain.

Celtic prowess combined with Carthaginian sailing skills to cross the Atlantic.

Griffhorn believes the Diodorus Siculus proves that the Carthaginians reached the Americas. Diodorus (Library of History 5.19-20) first describes an island, not a continent, “over against Libya”—meaning off the African coast—and states that it contains stately towns and fruitful plains when the Phoenicians discovered it:

Griffhorn believes the Diodorus Siculus proves that the Carthaginians reached the Americas. Diodorus (Library of History 5.19-20) first describes an island, not a continent, “over against Libya”—meaning off the African coast—and states that it contains stately towns and fruitful plains when the Phoenicians discovered it:The Phoenicians therefore, upon the account before related, having found out the coasts beyond the pillars, and sailing along by the shore of Africa, were on a sudden driven by a furious storm afar off into the main ocean; and after they had lain under this violent tempest for many days, they at length arrived at this island; and so, coming to the knowledge of the nature and pleasantness of this isle, they caused it to be known to everyone; and therefore the Tyrrhenians, when they were masters at sea, designed to send a colony thither; but the Carthaginians opposed them, both fearing lest most of their own citizens should be allured through the goodness of the island to settle there, and likewise intending to keep it as a place of refuge for themselves, in case of any sudden and unexpected blasts of fortune, which might tend to the utter ruin of their government: for, being then potent at sea, they doubted not but they could easily transport themselves and their families into that island unknown to the conquerors. (trans. G. Booth)

He, of course, leaves out the information Diodorus—and, crucially, pseudo-Aristotle three centuries earlier, unacknowledged here—gave about the location of this mysterious island, which regular readers will of course remember quite well from when these same texts were used by Harry Hubbard to claim ancient knowledge of North America, and also from America Unearthed, when Mark McMenamin used the same text from Diodorus to claim that the Phoenicians, not the Carthaginians, discovered America.

He, of course, leaves out the information Diodorus—and, crucially, pseudo-Aristotle three centuries earlier, unacknowledged here—gave about the location of this mysterious island, which regular readers will of course remember quite well from when these same texts were used by Harry Hubbard to claim ancient knowledge of North America, and also from America Unearthed, when Mark McMenamin used the same text from Diodorus to claim that the Phoenicians, not the Carthaginians, discovered America. Pseudo-Aristotle (De mirabilis auscultationibus 84) writes that:

In the sea outside the Pillars of Hercules they say that an island was discovered by the Carthaginians, desolate, having wood of every kind, and navigable rivers, and admirable for its fruits besides, but distant several days’ voyage from them. But, when the Carthaginians often came to this island because of its fertility, and some even dwelt there, the magistrates of the Carthaginians gave notice that they would punish with death those who should sail to it, and destroyed all the inhabitants, lest they should spread a report about it, or a large number might gather together to the island in their time, get possession of the authority, and destroy the prosperity of the Carthaginians. (trans. Launcelot D. Dowdall)

Griffhorn suggests from such texts that the Carthaginians had had secret communication with Brazil but kept it secret. This seems rather odd considering that the Carthaginians put up in the public square a commemoration of the voyage of Hanno to central Africa, where he saw chimpanzees. Surely they would have kept that secret, too, had that been their typical practice, as Griffhorn suggests.

At this point, the Carthaginians virtually vanish from the show because they were needed solely to give the Celts something they lack—ships—for Griffhorn’s real thesis, that the Celts are the ancestors of the Chachapoya and once reigned over South America.

The program tries to make the case that a boat could have crossed to Brazil using the ocean currents. Griffhorn places the discovery of Brazil by the Carthaginians and Celts at “1500 years before Columbus,” which would be about 10 BCE, long after the fall of Carthage. This makes no sense since Diodorus wrote between two and five decades earlier and pseudo-Aristotle three centuries before that—and both claimed the story reported much older events.

Griffhorn believes that the Carthaginian boat pilots traded with local cannibals (with what?) to survive, and Griffhorn believes that four symbols on the ancient petroglyphs on the rock of Ingá in Brazil aren’t just coincidentally close to geometrical shapes used in Celtiberian alphabets but are actual Celtic letters. Apparently the Carthaginian merchants were the merchant class serving the Celtic warrior elite.

Based on no evidence whatsoever, Griffhorn suggests that the Carthaginians and Celts on this voyage of discovery sailed up the Amazon. “No account exists, and we can only imagine” what they did, the narrator says, substituting early Spanish and Portuguese accounts to give an idea of what the Carthaginians “would have” seen and done. So, to recap: Everyone admits that no evidence exists, but they will nevertheless reconstruct an entire adventure based on analogies.

The narrator suggests that brightly-colored vases with geometric patterns made by the Marajoara culture of Brazil are “reminiscent” of Greek vases from the Classical period, decorated with Celtic spirals. This is a subjective judgment, and to my eyes the pots look nothing like the form of actual Greek vases, nor do the decorations bear more than a superficial resemblance to Old World patterns—no more so than any other Native geometric art. Geometric shapes tend to be the same everywhere. The trouble is that the Marajoara culture flourished after 800 CE, far too late to have anything to do with Mediterranean Greek vases from 1,000 years earlier.

We return to the metal axe from the opening that the show calls Celtic. It has no provenance, and was purchased from a merchant who said he found it in the jungle. The metal part of the axe is copper-zinc bronze, meaning that it was from the Old World, but the handle was made of Paraguayan wood. According to tests that the show says were run on the axe, the wood is 1500 years old. The most parsimonious explanation is that a Spanish, Portuguese, or African object was added to a sacred and ancient handle during the Contact period, but instead the show wants us to believe that Celts from 146 BCE dropped it en route to Peru where it was reused in 500 CE.

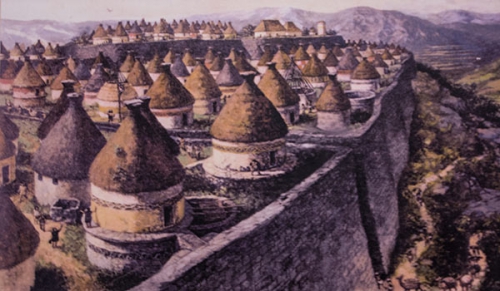

This brings us to the Chachapoya, and the show demands to know how mere Native people could possibly have learned how to build buildings, particularly round ones, without European help. Prof. Warren Church explains that the Chachapoya were quite able to build their own buildings, of which none date earlier than 500 CE. Griffhorn, however, sees the round buildings as unique in America and therefore of obviously Carthaginian extraction—700 years or more after the fact! He points to a carving of a face on a temple wall and says this is reminiscent of Celtic beheadings, as though no one else on earth ever drew faces or beheaded enemies. He also cites trepanation among the Celts and Chachapoya as another “connection.” Michael Schultz, a paleopathologist, makes an astonishing claim: that “Hippocratic accounts” from 500 BCE describe Chachapoyan trepanation! This is entirely untrue, and I have no idea where he got the idea that the Chachapoya were discussed in Greek literature.

Griffhorn believes that Spanish fortresses that are round must be connected to the Chachapoya’s round houses, even though this is about all they share in common. The show picks out painted images of shamans with antlers in both the Amazon and among the Celts and decides this must be a connection—even though, unacknowledged here, art from Mohenjo-Daro shows the same thing, as, in fact, does shamanic art everywhere, going back to the Stone Age.

This is really going nowhere fast.

Schultz returns again to assert that pre-Contact Chachapoya mummies suffered from tuberculosis, a disease previously thought only to have come with the Spanish. This “new” fact, however, has been known since 2002, and the presence of tuberculosis in the pre-Columbian Americas has been known since 1994—it’s been found beyond just the Chachapoya—but Griffhorn takes this as a revelation that the Carthaginians brought “Classical” tuberculosis (whatever that means—he seems to think the disease was different in Antiquity) with them in 146 BCE, where it lay dormant for a thousand years. Archaeologists suggest that the disease arose from llamas, who are known to carry the bovine form of tuberculosis—or even from the Polynesians who reached South America before Columbus.

Next, various Chachapoyan traits are compared to Spanish, Majorcan, and other cultures from various time periods, as though the Chachapoyans simply adopted one trait from each of the ark of cross-cultural European outcasts from multiple time periods who sailed up the Amazon to meet them.

The show points to the fair-skinned, blonde-haired Chachapoyan descendants as evidence that that some Chachapoyans are “distinctive” from the “dark haired” and “brown-skinned” Natives, and we hear what Cieza de Leon had to say about this, though the paraphrase offered by Warren Church sounds to me like he’s running together bits and pieces from both Cieza de Leon and from Pedro Pizarro, who famously wrote:

The Indian women of the Guancas and Chachapoyas and Cañares were the common women, most of them being beautiful. The rest of the womanhood of this kingdom were thick, neither beautiful nor ugly, but of medium good-looks. The people of this kingdom of Peru were white, swarthy in colour, and among them the Lords and Ladies were whiter than Spaniards. I saw in this land an Indian woman and a child who would not stand out among white blonds. These people [of the upper class] say that they were the children of the idols. (Relation of the Discoveries etc., trans. Philip Ainsworth Means, p. 430)

These Indians of Chachapoyas are the most fair and good-looking of any that I have seen in the Indies, and their women are so beautiful that many of them were worthy to be wives of the Yncas, or inmates of the temples of the sun. To this day the Indian women of this race are exceedingly beautiful, for they are fair and well formed. They go dressed in woollen cloths, like their husbands, and on their heads they wear a certain fringe, the sign by which they may be known in all parts. After they were subjugated by the Yncas, they received the laws and customs according to which they lived, from them. They adored the sun and other gods, like the rest of the Indians, and resembled them in other customs, such as the burial of their dead and conversing with the devil. (trans. Clements Markham)

The show concludes that there is no “smoking gun,” only suggestive indications that the Chachapoya are not really Native Americans on the same stripe as the brown ones but owe their culture, their art, their religion, and their very genes to a boatload of Carthaginians and Celts who sailed up the Amazon in 146 BCE and, by dint of their superior European prowess, took over to such an extent that their potent DNA still rules the region 1,868 years later, largely undiluted by the intervening centuries.

I guess this means that they’re all inbred, but the show doesn’t go there.

This was really terrible, and the only significant difference between this show and America Unearthed in terms of quality of evidence and the desire to find hidden white people in the Americas is that this show searched South America rather than North America, and its hero never claimed that there was a conspiracy trying to suppress his work.

00:05 Publié dans archéologie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : archéologie, pérou, chachapoyas, andes, amérique latine, amérique du sud, américanologie, civilisations pré-colombiennes, archéologie andine |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Kamen die Kelten bis nach Amerika?

Kamen die Kelten bis nach Amerika?

von FOCUS-Online-Autor Harald Wiederschein

Ex: http://www.focus.de

In der Antike segelten Mittelmeerbewohner über den Atlantik und ließen sich in den Anden nieder – sagt der Forscher Hans Giffhorn und präsentiert eine Fülle von Indizien. Doch andere Wissenschaftler sind skeptisch.

Christoph Kolumbus war nicht der Erste, der von Europa nach Amerika segelte. Spätestens seit Archäologen vor einigen Jahrzehnten die Siedlung L’Anse aux Meadows an der Nordspitze Neufundlands ausgruben und damit eine alte isländische Saga bestätigten, war klar: Die Wikinger hatten den Atlantik bereits 500 Jahre vor dem italienischen Seefahrer überquert und sich zumindest für kurze Zeit in der „Neuen Welt“ niedergelassen.

Uneinig sind sich Historiker und Archäologen allerdings, ob noch anderen der Sprung über den Ozean gelungen sein könnte – möglicherweise lange bevor die Nordmänner zu ihren Entdeckungsfahrten aufbrachen. Dem irischen Mönch Brendan vielleicht, der – wie eine im Mittelalter weit verbreitete Erzählung berichtet – eine Insel weit im Westen gefunden haben soll? Muslimischen Seefahrern oder zuvor schon Griechen, Römern oder den Alten Ägyptern? „Eine Zeit lang hatten solche Ideen Konjunktur, doch inzwischen werden sie weniger und auch kritischer diskutiert“, sagt Ronald Bockius, Experte für antike Schifffahrt am Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseum in Mainz.

Hochentwickelte Kultur am Ostrand der Anden

Kann nun ein neues Buchder Diskussion wieder Auftrieb geben? „Wurde Amerika in der Antike entdeckt?“ lautet sein Titel, verfasst von dem deutschen Kulturwissenschaftler Hans Giffhorn. Darin entwirft er das Szenario, karthagische Seeleute hätten im 2. Jahrhundert vor Christus zusammen mit keltischen Kriegern und Söldnern aus Mallorca den Atlantik überquert. Ziel sei es gewesen, den Römern, die damals die rivalisierende Metropole Karthago in Nordafrika zerstörten, zu entkommen. Ebenfalls per Schiff hätten die Flüchtlinge anschließend das Amazonas-Gebiet durchquert und zuletzt im Nordosten des heutigen Perus eine neue Kultur begründet: die der Chachapoya.

Bis heute wissen Forscher nur wenig über das Volk, das einst am Ostrand der Anden siedelte. Um 800 nach Christus – so der bisherige Kenntnisstand – tauchten die Chachapoya aus dem Dunkel der Geschichte auf. Die Überreste einer riesigen Stadt, eine mächtige Festung mit 15 Meter hohen Mauern, Sarkophage und Mumienfunde zeugen von einer hochentwickelten Kultur. „Nebelwaldmenschen“ nannten die Inka die Chachapoya, die angeblich sehr kriegerisch waren – trotzdem mussten sie sich im 15. Jahrhundert der neuen Großmacht geschlagen geben. Die Überlebenden verbündeten sich später mit den Spaniern und halfen ihnen, das Inkareich zu zerstören. Doch es half ihnen nichts: Ihre Freiheit erlangten sie nicht zurück, stattdessen gingen sie an aus Europa eingeschleppten Krankheiten zugrunde.

Europäische Stammväter eines Indiovolks?

Können antike Kelten und Karthager wirklich die Stammväter dieses rätselhaften Andenvolks sein – auf einem anderen Kontinent, rund 9000 Kilometer entfernt? Auf den ersten Blick klingt das nach einem phantastischen Konstrukt à la Erich von Däniken. „Früher war ich auch der Meinung, eine solches Szenario sei vollkommen unrealistisch“, sagt Giffhorn. „Aber mittlerweile – nach vierzehnjähriger Forschung zu dem Thema – halte ich es für die plausibelste Erklärung zahlloser bislang rätselhafter Phänomene.“

Bei seinen vielen Reisen sei ihm zum Beispiel aufgefallen, wie sehr die Rundbauten der Chachapoya den Überresten keltischer Wohnhäuser im nordwestlichen Spanien glichen, sagt Giffhorn. Kaum ein anderes Indiovolk habe auf diese Weise gebaut. Auch seien die Chachapoya wie die Kelten Kopfjäger gewesen. Und die kriegerischen Andenbewohner hätten mit Steinschleudern genau wie die Bewohner Mallorcas gekämpft – um nur einige Indizien zu nennen, die der Kulturwissenschaftler zur Untermauerung seiner These anführt.

00:05 Publié dans archéologie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : kuelpa, chachapoyas, archéologie, amérique latine, amérique du sud, pérou, civilisations pré-colombiennes, celtibères, carthaginois, américanologie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 14 avril 2010

D'où venaient les premiers Américains?

Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 2004

D’où venaient les premiers Américains ?

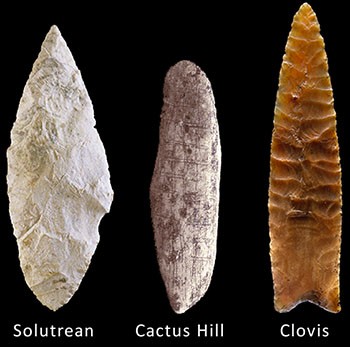

Lorsque les Européens de l’époque de Christophe Colomb arrivèrent en Amérique, ils trouvèrent sur place des hommes qui ressemblaient plus à des Asiatiques (Chinois. Japonais ou Coréens) qu’à toute autre population. Depuis lors, l’opinion a prévalu selon laquelle les ancêtres des Indiens d’Amérique auraient émigré à partir de l’Asie du Nord. en suivant le détroit de Behring, via la Sibérie et l’Alaska, il y a environ 12 000 ans. La culture de Clovis, découverte en 1932 au Nouveau-Mexique et qui a pu être datée de 11 500 ans, a donc été longtemps considérée comme la première culture humaine qui se soit développée sur le sol américain. Ce sont les héritiers de cette culture qui auraient progressivement peuplé tout le Nouveau Monde. Mais plusieurs faits nouveaux ont récemment conduit les chercheurs à remettre en cause cette théorie, dite “Clovis First».

Lorsque les Européens de l’époque de Christophe Colomb arrivèrent en Amérique, ils trouvèrent sur place des hommes qui ressemblaient plus à des Asiatiques (Chinois. Japonais ou Coréens) qu’à toute autre population. Depuis lors, l’opinion a prévalu selon laquelle les ancêtres des Indiens d’Amérique auraient émigré à partir de l’Asie du Nord. en suivant le détroit de Behring, via la Sibérie et l’Alaska, il y a environ 12 000 ans. La culture de Clovis, découverte en 1932 au Nouveau-Mexique et qui a pu être datée de 11 500 ans, a donc été longtemps considérée comme la première culture humaine qui se soit développée sur le sol américain. Ce sont les héritiers de cette culture qui auraient progressivement peuplé tout le Nouveau Monde. Mais plusieurs faits nouveaux ont récemment conduit les chercheurs à remettre en cause cette théorie, dite “Clovis First».

L’un de ces faits est la découverte à Monte Verde, au Chili, par Tom D. Dillehay, de l’Université du Kentucky, d’un ensemble d’artefacts humains vieux de 12 500 ans, soit un millénaire de plus que la culture de Clovis, alors que cette dernière se situe beaucoup plus au nord. C’est également le cas d’autres artefacts qui ont été découverts depuis dans un abri rocheux situé à Meadow Croft, près de Pittsburgh, en Pennsylvanie.

A ces données archéologiques s’en ajoutent d’autres, de type anthropologique. Plusieurs crânes ou squelettes vieux de plus de 8000 ans retrouvés en Amérique du Nord ou du Sud présentent en effet des caractères très différents de ceux des populations mongoloïdes. Le plus célèbre est le squelette remarquablement conservé de l’homme de Kennewick, découvert en 1996 sur les berges de la rivière Columbia, dans l’État d’Eastern Washington. Ce squelette, daté au radiocarbone de 9400 ans, présente des caractères typiquement européens. Il en va de même de la femme de Pehon, âgée au moment de sa mort d’environ 25 ans, qui a été retrouvée en 1959 dans la banlieue de Mexico et a été datée récemment de quelque 15 000 ans. Par ailleurs, un squelette de femme ("Luzia») découvert au Brésil et vieux d’au moins 11 500 ans présente, lui. des caractères typiquement négroïdes semblables à ceux des habitants primitifs de l’Australie et de la Polynésie.

L’ancienne population européenne présente en Amérique pourrait avoir été apparentée aux Aïnous, qui vivent actuellement dans l’île japonaise de Hokkaïdo. Elle serait donc elle aussi passée par le détroit de Behring. Cependant, Denis Stanford et Bruce Bradley, de la Smithsonian Institution, pensent qu’il pourrait très bien s’agir d’Européens de l’Ouest, qui auraient traversé l’Atlantique Nord à une période très reculée. Les deux chercheurs s’appuient notamment sur la ressemblance frappante existant entre les plus anciens outils de pierre taillée mis au jour en Amérique et l’industrie solutréenne attestée en Espagne et dans le Sud-Ouest de la France il y a 20 000-16 000 ans.

L’hypothèse qui prévaut désormais est donc celle d’un peuplement de l’Amérique beaucoup plus complexe qu’on ne le pensait jusqu’à présent. Celui-ci pourrait avoir commencé au pléistocène, il y a au moins 30 000 ans. à la fois en provenance de l’Europe, de l’Asie et de l’Australie.

(Sources: New York Times. 30 juin 2002: National Geographic, septembre 2002: Science Insights News. décembre 2002. In Eléments N°111)

00:05 Publié dans archéologie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : archéologie, américanologie, préhistoire, migrations humaines, migrations, amérique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook