Vintila Horia was a Romanian Traditional author. In a collection dedicated to the thought of Rene Guenon, titled Rene Guenon Colloque du Centenaire, he contributed an essay Mon Chemin de Dante à Guenon, or, My Path from Dante to Guenon. (I’m looking for a hard or soft copy of the full text if anyone can find it.)

Vintila Horia was a Romanian Traditional author. In a collection dedicated to the thought of Rene Guenon, titled Rene Guenon Colloque du Centenaire, he contributed an essay Mon Chemin de Dante à Guenon, or, My Path from Dante to Guenon. (I’m looking for a hard or soft copy of the full text if anyone can find it.)

The Project Rene Guenon published some excerpts from it here. In the section below titled “Reading Notes”, there is my translation of the notes from French to English.

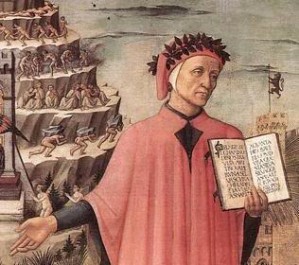

Even this little taste is quite suggestive. Usually applied to Sacred Texts, Horia points out that the Divine Comedy by Dante can also be understood on four levels. It is no surprise that he names Rene Guenon as providing to key to the highest level of interpretation.

An interesting wrinkle is that Horia names Soren Kierkegaard as providing to key to understand the Comedy at the moral level. That is certainly worth exploring. Kierkegaard describes the phenomenological states of consciousness for many types of men. Perhaps then, we should understand Dante’s descriptions of the punishments of hell for the various class of sinners as pictorial representations of their inner soul life.

Horia then points out the roles of the Cross and the Eagle, i.e., Church and Empire (or Spiritual Authority and Temporal Power, in Guenon’s terms). A one-sided effort is certain to fail.

Horia ends on a note reminiscent of Boris Mouravieff: a small group of the just will witness the coming Age of the Holy Spirit.

Reading Notes

There are several keys to Dante. Rene Guenon provides us one: that of esoterism, which would make the “Divine Comedy” the poem par excellence from the standpoint of traditional studies. (p 93)

Among the studies devoted to Dante, the closest to the poet’s spirit are:

- that of Rene Guenon

- that of the Italian scholar Luigi Valli

- that of the Spaniard Asin Palacios, entitled “Dante and Islam.”

“With the fourteenth century, and especially with Petrarch, the path takes a turning point, it tries to rise, with the return of Platonism to power, along the first part of the Renaissance at least, but it sinks, after Marsilio Ficino, into a hopeless landscape, or terminal end, of which the eighteenth century constitutes a type of spiritualist error, so to speak, by following the teaching that Guenon suggests to us as an example of what we should not do especially at times when poetry, like politics together, as in Dante’s time a tragic inseparability. Hölderlin, already at the beginning of the last century, placed in relation the “times of distress” and the “presence of the poet.” (p 94)

Our time is perhaps one of the closest to Dantean exegesis.

“Dante was above all a poet faithful to poiesis and then to creation, and, in the most logical way, he found himself tempted by all the paths to the very source of creation, which is Truth. To reach it, he let himself be guided by the two poles of our poetic soul: inspiration, which proceeds in a straight line from the unconscious world, and reason, linked to the consciousness above any partial separation, classical in one sense, romantic in another, and which removed from his work that tone of impartiality — I would not say objectivity, because this word has no meaning in this context — that characterizes it despite permanent injunctions of his ego and of the historical sufferings that inspire it and, often, determine it in his creative action. Dante is a world, in the fullest sense, and it even lets us embrace it, even if we are situated almost seven centuries after his adventure.” (p 94)

There is a literary key of “The Divine Comedy” and of Dante in general. Next, there is an allegorical key, which is a first way to add a veil above the literal sense. Then a moral key, proposed by Kierkegaard. The last one, the anagogical key, was given by Guenon and Luigi Valli.

“What Guenon did for me and, I imagine, for most of those who found in him the same remedy, was to draw me away from minor or partial truths, to put me in contact, at least wavering, with Truth, which is one and that, by following ever more complicated and hidden paths, drew me to Plato and made me understand the most prominent and the most spectacular aspects of current physics, for example, through Heisenberg, to name a stage, as efforts as part of a broader effort whose aim was that to help me advance towards something after going through hell — the last two centuries of history Western form, in this perspective, the nine circles of hell and it is possible that we are going through the last, that of eternal ice and traitors, those who betrayed man — to lead us to an indispensable Purgatory to make the last jump, one that implies an end and a beginning, and that is surely one of the end and a new beginning, ‘Pure and disposed to mount unto the stars’, which is the last verse of Dante’s Purgatory.” (p 97)

The metapolitical goal of “The Divine Comedy” is to present to a sick mankind the double remedy of the Cross (the Catholic Church) and the Eagle (the Empire). The Cross has the role to cure ignorance and the Eagle, distress. Lust was to be annihilated by the victory of the Cross, and injustice by the victory of the Eagle.

“So don’t we owe our terrible entrance into the deterministic and entropic night to the separation between the Cross and the Eagle? The Cross alone would now solve the problems that it could solve neither at the end of the Middle Ages, when it was strong and universal, nor in the age of the Revolution, when it was abandoned by poets causing the flight of the gods which Hölderlin speaks about. The Eagle soared, too, on other worlds, very far away from us, imitated by fake eagles, imperial in space but not in time, which belongs to the reign of the Cross. We live under the oppression of invalid empires, not only because sick of tyranny and inhumane separations, fated to protect the ultimate fall and decay, but also because they do not want the Cross, their most mysterious and fiercest enemy, alone but surviving. I think that Dante and Guenon complement each other on the threshold of the catastrophic loss of the relationship with being and of finding again complementary phases in the path of salvation that explain the history of this time with a clarity that other specialized disciplines are not able to explain because they unable to understand. Beyond the end of time, that time already many centuries old, we may find ourselves in the fullness of Being, according to the voice full of the bitterness and hope of the best prophets. Everything will only be the pile of the useless, arrogant and vain. Only a voice of the righteous, that is to say, those that have been formed in a different light, will accompany us in the great alchemical change in the third millennium.” (p 100-101)

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg