mardi, 15 juin 2010

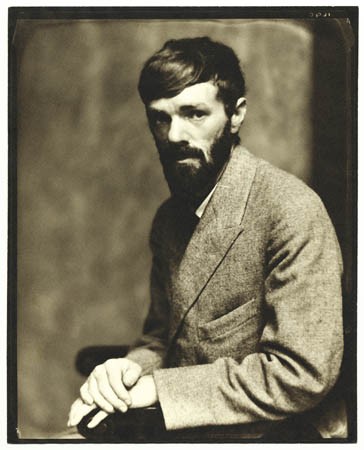

D. H. Lawrence

D.H. Lawrence |

| Ex: http://www.oswaldmosley.com/ D.H. Lawrence 1885-1930 is acknowledged as one of the most influential novelists of the 20th Century. He wrote novels and poetry as acts of polemic and prophecy. For Lawrence saw himself as both a prophet and the harbinger of a New Dawn and as a leader-saviour who would sacrificially accept the tremendous responsibilities of political power as a dictator so that humanity could be free to get back to being human. Much of Lawrence's outlook is reminiscent of Jung and Nietzsche but, although he was acquainted with the works of both, his philosophy developed independently. Lawrence was born in Eastwood, a coal-mining town near Nottingham, into a family of colliers. His father was a heavy drinker, and his mother's commitment to Christianity imbued the house with continual tension between the parents. At college, he was an agnostic and determined to become a poet and an author. Having rejected the faith of his mother, Lawrence also rejected the counter-faith of science, democracy, industrialisation and the mechanisation of man. LOVE, POWER AND THE "DARK LORD"

Love and power are the two "threat vibrations" which hold individuals together, and emanate unconsciously from the leadership class. With power, there is trust, fear and obedience. With love, there is "protection" and "the sense of safety". Lawrence considers that most leaders have been out of balance with one or the other. That is the message of his novel Kangaroo. Here the Englishman Richard Lovat Somers although attracted to the fascist ideology of "Kangaroo" and his Diggers movement, ultimately rejects it as representing the same type of enervating love as Christianity, the love of the masses, and pursues his own individuality. The question for Somers is that of accepting his own dark master (Jung's Shadow of the repressed unconscious). Until that returns no human lordship can be accepted: "He did not yet submit to the fact of what he HALF knew: that before mankind would accept any man for a king. Before Harriet would ever accept him, Richard Lovat as a lord and master he, this self-same Richard who was strong on kingship, must open the doors of his soul and let in a dark lord and master for himself, the dark god he had sensed outside the door. Let him once truly submit to the dark majesty, creaking open his doors to this fearful god who is master, and entering us from below, the lower doors; let himself once admit a master, the unspeakable god: the rest would happen." What is required, once the dark lord has returned to men's souls in place of undifferentiated 'love' is a social order based on a hierarchical pyramid culminating in a dictator. The dictator would relieve the masses of the burden of democracy. This new social order would be based on the balance of power and love, something of a return to the medieval ideal of protection and obedience. The ordinary folk would gain a new worth by giving obedience to the leader, who would in turn assume an awesome responsibility and would lead by virtue of his being "circuited" to the cosmos. Through such a redeeming philosopher-king individuals could reconnect cosmically and assume Heroic proportions through obedience to Heroes. "Give homage and allegiance to a hero, and you become yourself heroic, it is the law of man." HEROIC VITALISM In 1921 he wrote: "I don't believe in either liberty or democracy. I believe in actual, sacred, inspired authority." It is mere intellect, soulless and mechanistic, which is at the root of our problems; it restrains the passions and kills the natural. His essay on Lady Chatterley's Lover deals with the social question. It is the mechanistic, arising from pure intellect, devoid of emotion, passion and all that is implied in the blood (instinct) that has caused the ills of modern society. "This again is the tragedy of social Itfe today. In the old England, the curious blood connection held the classes together. The squires might be arrogant violent, bullying and unjust, yet in some ways they were at one with the people, part of the same blood stream. We feel it in Defoe or Fielding. And then in the mean Jane Austen, it is gone...So, in Lady Chatterley's Lover we have a man, Sir Clifford, who is purely a personality, having lost entirely all connection with his fellow men and women, except those of usage. All warmth is gone entirely, the hearth is cold the heart does not humanly exist. He is a pure product of our civilisation, but he is the death of the great humanity of the world." Against this pallid intellectualism, the product the late cycle of a civilisation, writing in 1913 Lawrence posited: "My great religion is a belief in the blood, as the flesh being wiser than the intellect. We can go wrong in our minds but what our blood feels and believes and says, is always true." The great cultural figures of our time, including Lawrence, Yeats, Pound and Hamsun, were Thinkers of the Blood, men of instinct, which has permanence and eternity. Rightly, the term intellectual became synonymous since the 1930s with the "Left", but these intellectuals were products of their time and the century before. They are detached from tradition, uprooted, alienated bereft of instinct and feeling. The first 'Thinkers of the Blood' championed excellence and nobility, influenced greatly by Nietzsche, and were suspicious, if not terrified of the mass levelling results of democracy and its offspring communism. In democracy and communism, they saw the destruction of culture as the pursuit of the sublime. Their opposite numbers, the intellectuals of the Left, celebrated the rise of mass-man in a perverse manner that would, if communism were universally triumphant, mean the destruction of their own liberty to create above and beyond the state commissariats. Lawrence believed that socialistic agitation and unrest would create the climate, in which he would be able to gather around him "a choice minority, more fierce and aristocratic in spirit" to take over authority in a fascist like coup, "then I shall come into my own." Lawrence's rebellion is against that late or winter phase of civilisation, which the West has entered as, described by Spengler. It is marked by the rise of the city over the village, of money over blood connections. Like Spengler, Lawrence's conception of history is cyclic, and his idea of society organic. The great cultural figures of our time, including Lawrence, Yeats, Pound and Hamsun, were Thinkers of the Blood, men of instinct, which has permanence and eternity. Rightly, the term intellectual became synonymous since the 1930s with the "Left", but these intellectuals were products of their time and the century before. They are detached from tradition, uprooted, alienated bereft of instinct and feeling. The first 'Thinkers of the Blood' championed excellence and nobility, influenced greatly by Nietzsche, and were suspicious, if not terrified of the mass levelling results of democracy and its offspring communism. In democracy and communism, they saw the destruction of culture as the pursuit of the sublime. Their opposite numbers, the intellectuals of the Left, celebrated the rise of mass-man in a perverse manner that would, if communism were universally triumphant, mean the destruction of their own liberty to create above and beyond the state commissariats. Lawrence believed that socialistic agitation and unrest would create the climate, in which he would be able to gather around him "a choice minority, more fierce and aristocratic in spirit" to take over authority in a fascist like coup, "then I shall come into my own." Lawrence's rebellion is against that late or winter phase of civilisation, which the West has entered as, described by Spengler. It is marked by the rise of the city over the village, of money over blood connections. Like Spengler, Lawrence's conception of history is cyclic, and his idea of society organic. RELIGION OLD AND NEW It was in Mexico that he encountered the Plumed Serpent, Quetzalcoatl, of the Aztecs. Through a revival of this deity and the reawakening of the long repressed primal urges, Lawrence thought that Europe might be renewed. To the USA, he advised that it should look to the land before the Spaniards and the Pilgrim Fathers and embrace the 'black demon of savage America'. This 'demon' is akin to Jung's concept of the Shadow, (and its embodiment in what Jung called the "Devil archetype"), and bringing it to consciousness is required for true wholeness or individuation. Turn to "the unresolved, the rejected", Lawrence advised the Americans (Phoenix). He regarded his novel The Plumed Serpent as his most important; the story of a white women who becomes immersed in a social and religious movement of national regeneration among the Mexicans, based on a revival of the worship of Quetzalcoatl. Looking about Europe for such a heritage, he found it among the Etruscans and the Druids. Yet although finding his way back to the spirituality that had once been part of Europe, Lawrence does not advocate a mimicing of ancient ways for the present time; nor the adoption of alien spirituality for the European West, as is the fetish among many alienated souls today who look at every culture and heritage except their own. He wishes to return to the substance, to the awe before the mystery of life. "My way is my own, old red father: I can't cluster at the drum anymore", he writes in his essay Indians and an Englishman. Yet what he found among the Indians was a far off innermost place at the human core, the ever present as he describes the way Kate is affected by the ritual she witnesses among the followers of Quetzalcoatl. In The Woman Who Rode Away the wife of a mine owner tired of her life leaves to find a remote Indian hill tribe who are said to preserve the rituals of the old gods. She is told that the whites have captured the sun and she is to be the messenger to tell them to return him. She is sacrificed to the sun... It is a sacrifice of a product of the mechanistic society for a reconnection with the cosmos. For Lawrence the most value is to be had in "the life that arises from the blood" THE LION, THE UNICORN AND THE CROWN The problems Lawrence brought under consideration have become ever more acute as our late cycle of Western civilisation draws to a close, dominated by money and the machine. Lawrence, like Yeats, Hamsun, Williamson and others, sought a return to the Eternal, by reconnecting that part of ourselves that has been deeply repressed by the "loathsome spirit of the age".

|

00:15 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, lettres, lettres naglaises, littérature anglaise, angleterre, vitalisme, panthéisme, paganisme, philosophie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

For Lawrence capitalism destroyed the soul and the mystery of life, as did democracy and equality. He devoted most of his life to finding a new-yet-old religion that will return the mystery to life and reconnect humanity to the cosmos.

For Lawrence capitalism destroyed the soul and the mystery of life, as did democracy and equality. He devoted most of his life to finding a new-yet-old religion that will return the mystery to life and reconnect humanity to the cosmos.