mercredi, 30 juillet 2025

Rudolf Kjellén et le caractère national suédois

Rudolf Kjellén et le caractère national suédois

par Joakim Andersen (2011)

Source: https://motpol.nu/oskorei/2011/04/23/rudolf-kjellen-och-d...

Comparé à beaucoup d’autres pays européens, le public suédois a adopté en 1968 les idées dans le vent de cette année-charnière avec une conviction inhabituelle. Par exemple, un parti critique envers l’immigration n’a été intégré au Parlement que tard dans l’histoire, et en ce qui concerne l’influence de la communauté queer sur la politique, la Suède apparaît comme une exception. Plusieurs explications peuvent être avancées, toutes comportant une part de vérité. Il peut notamment être mentionné que notre pays a longtemps été épargné par la guerre, surtout dans ses régions centrales, ainsi que par la longue domination politique de la social-démocratie et a éprouvé le besoin d’une nouvelle base idéologique. La position historiquement forte de l’État suédois, ainsi que l’individualisme que Berggren et Trägårdh considèrent comme caractéristique du Suédois, peuvent également expliquer la facilité avec laquelle les idées de 1968 ont façonné notre vie publique.

On peut aussi ajouter le caractère suédois, décrit déjà par Rudolf Kjellén au début du 20ème siècle. Kjellén explique cela pour justifier pourquoi une science politique moderne a eu du mal à s’imposer en Suède, mais cela s’applique aussi à notre problème :

On peut aussi ajouter le caractère suédois, décrit déjà par Rudolf Kjellén au début du 20ème siècle. Kjellén explique cela pour justifier pourquoi une science politique moderne a eu du mal à s’imposer en Suède, mais cela s’applique aussi à notre problème :

On a souvent entendu dire – pour ne pas répéter une vérité bien reconnue – que le don politique ne fait pas partie des vertus dont notre peuple suédois a été doté généreusement. Il suffit de regarder de l’autre côté du détroit d’Øresund pour sentir notre faiblesse à ce sujet. Elle est aussi apparentée à la faiblesse pour le métier de commerçant, souvent soulignée chez nous; derrière cela se trouve, comme racine commune, un esprit peu développé pour saisir les réalités psychologiques. Notre histoire a été plus riche en héros de guerre qu’en hommes d’État; et même après l’extinction de leur espèce, par manque de demande, il semble que ceux-ci ne se soient pas beaucoup renouvelés.

Kjellén note également que le Suédois appartient à un peuple plus susceptible d’être influencé par son environnement :

“… il est également évident que le degré de nationalité varie selon les peuples. L’ Anglais ou le Chinois, qui restent eux-mêmes dans toutes les situations et tous les rapports, contrastent sans aucun doute fortement – déjà à cet égard – avec l’Allemand ou le Japonais, qui sont plus sensibles à la pression de leur environnement, plus enclins à « suivre la mode » ; c’est pourquoi ces derniers ne s’intègrent pas aussi facilement à leur environnement que l’Allemand ou le Suédois en Amérique, tout comme autrefois le Wisigoth en Espagne ou le Danois en Normandie. Il semble vraiment qu’il y ait dans l’esprit de chaque nation une certaine identité nationale plus ou moins marquée dès le départ.”

Aujourd’hui, dans les médias, nous pouvons souvent reconnaître un intérêt pour ce qui est typiquement suédois, même si c’est sous une forme très prudente (“la curiosité qui n’ose pas dire son nom”). Kjellén a ici un avantage évident, car contrairement à notre époque, il n’a pas été diabolisé ou rejeté totalement de l'orbite de sciences telle la psychologie populaire :

L’anthropologie et la psychologie populaire apparaissent comme des sciences auxiliaires de la politique ; alors qu’elles seraient totalement vides si aucune réalité nationale n’existait. La dernière discipline a beaucoup à nous apprendre, car la politique pratique repose en grande partie sur une appréciation juste des caractères réels et de la profondeur de l’esprit des nations. Les états d’âme passagers jouent un rôle moins important que les traits de caractère véritables ; ce sont ces derniers qui apparaissent comme des facteurs objectifs – que ce soit en ce qui concerne l’intelligence en général, comme chez les peuples blancs, ou l’habileté à gouverner, comme chez les Romains et les Russes, par rapport aux Grecs esthétisants et aux « Petits Russiens », ou encore l’habileté commerciale, comme chez les Chinois et les Danois face aux Japonais et aux Suédois, ou la capacité diplomatique, comme chez les Anglais face aux Allemands, ou encore l’organisation technique, comme chez les Allemands par rapport aux Anglais.

On peut supposer que les Suédois, un peuple qui a formé de nombreux ingénieurs et inventeurs, ont en réalité plus en commun avec l’Allemand qu’avec l’Anglais dans cette dernière comparaison. En même temps, il existe une tendance à la conformité, à l’idéalisme et à un manque de don politique, ce qui fait que, de nos jours, le Suédois prend très au sérieux le culte de l’idéal perceptible chez d’autres peuples. Kjellén donne cependant aussi des raisons d’être optimiste :

On peut supposer que les Suédois, un peuple qui a formé de nombreux ingénieurs et inventeurs, ont en réalité plus en commun avec l’Allemand qu’avec l’Anglais dans cette dernière comparaison. En même temps, il existe une tendance à la conformité, à l’idéalisme et à un manque de don politique, ce qui fait que, de nos jours, le Suédois prend très au sérieux le culte de l’idéal perceptible chez d’autres peuples. Kjellén donne cependant aussi des raisons d’être optimiste :

Il faut observer que, comme les enfants, les nations ignorent longtemps les ressorts de leur propre existence… mais finalement, il arrive que la solidarité devienne une force dans leur âme ; cette expérience peut surgir soudainement, comme une décharge électrique, après une longue accumulation, ou comme une étincelle qui embrase tout. Cela se produit typiquement sous une pression extérieure intense ; c’est dans la détresse que la nation apprend à se connaître elle-même. Le peuple suédois, jusqu’ici divisé en petites communautés régionales, a appris cela à l’époque d’Engelbrekt sous la domination danoise. La France, battue et désespérée, a vécu la même expérience lorsque Jeanne d’Arc a levé sa bannière contre les Anglais… Lorsqu’une conscience de faire partie d’une entité supérieure et plus grande s’empare pour la première fois des membres d’une nation, alors cette nation est vraiment “devenue un homme”. Sur ce point, le processus devient politique.

En termes marxistes, on peut dire que le processus que Kjellén décrit est une évolution du « peuple en soi » vers le « peuple pour soi ». Les membres d’un peuple en soi ont beaucoup en commun, mais n’en ont pas conscience, par exemple parce qu’ils ont longtemps eu peu d’opportunités de se comparer à d’autres peuples. Un peuple pour soi est conscient de ce qui les unit et est prêt à défendre politiquement ses intérêts. Une hypothèse plausible est que la société multiculturelle finira par faire des Suédois un peuple pour soi, avec des effets bien plus importants que ceux que souhaite l’élite.

20:32 Publié dans Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : rudolf kjellen, suède, scandinavie, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 09 avril 2019

Rudolf Kjellen and Friedrich Naumann “Middle Europe”

Rudolf Kjellen and Friedrich Naumann “Middle Europe”

2.1 Defining a New Science

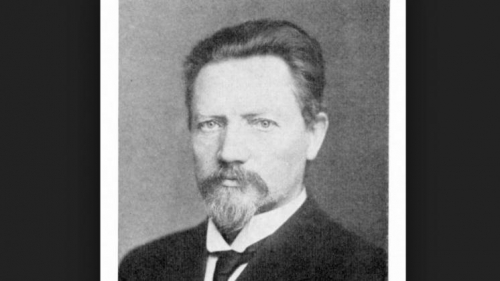

A Swede, Rudolf Kjellen, was the first to use the term “Geopolitics.”

Kjellen was a professor of history and political science at the University of Uppsalla and Goteborg University. However, he was an active participant in politics, he held a seat in parliament, and his politics were distinguished by an underlying Germanophilic orientation. Kjellen was not a professional geographer, but he developed the basics of geopolitics as part of political science. His work originated from Ratzel’s (he considered him to be his mentor).

Kjellen’s geopolitics can be identified in the following passage: “This—the science of governments (states) as geographical organisms—is incarnate in the land.”

Apart from “Geopolitics,” Kjellen proposed four more neologisms, which in his view should be the basis for the partition of political science into separate sections.

-

Ecopolitics: “The study of dynamics impulses, transferred from the people to the state.”

-

Demopolitics: “The study of dynamic impulses transferred from the people to the state,” an analogue is Ratzel’s “Anthrogeography.”

-

Sociopolitical: “The study of the social aspect of the state.”

-

Kratospolitics: “The study of the forms of governments and powers in relation to the problems of rights and socioeconomic factors.”

But all of these disciplines, which Kjellen cultivated in parallel with geopolitics, did not receive more widespread recognition aside from the term “Geopolitics,” which steadily became established in quite varied circles.

But all of these disciplines, which Kjellen cultivated in parallel with geopolitics, did not receive more widespread recognition aside from the term “Geopolitics,” which steadily became established in quite varied circles.

2.2 The State as a Life Form and Interests in Germany

In his foundational work “The State as a Life Form” (1916), Kjellen developed postulations that had been hypothesized by Ratzel in his works. Kjellen, similar to Ratzel, considered himself a believer in German “Organicism,” rejecting the mechanistic state and society approach. The rejection of the strict bleaching of study in terms of “inanimate objects” (background), and “human subjects” (personalities), is a distinctive feature of geopolitics. In this sense, the very meaning of geopolitics is displayed in Kjellen’s work.

Kjellen developed Ratzel’s geopolitical principles and applied them to specific historical situations in his contemporary Europe.

He followed Ratzel’s idea of “a continental state” to its logical conclusion and applied it to Germany. He showed that in the European context Germany constitutes that space, which possesses the pivotal dynamism and is intended to structure itself to become encircled by the remaining European powers. Kjellen interpreted World War I to be a natural conflict arising between a dynamic, expanding Germany (Axis nations) opposed by the peripheral European (and non-European) states (the Entente). Differences in the dynamics of geopolitical growth—downwards for England and France and upwards for Germany— predetermined the basic alignment of forces. Wherein, from his point of view, this is the natural and inevitable geopolitical position for Germany, despite the temporary defeat in World War I.

Kjellen consolidated Ratzel’s geopolitical maxims that were in the interests of Germany (= the interests of Europe), in opposition to the interests of the Western European powers (especially England and France). But Germany, a “young” state, and the Germans, a “young people” (this idea—of “young peoples,” which is what Russians and Germans were considered to be—dates back to Fyodor Dostoevsky, who was quoted more than once by Kjellen).

The “young” Germans, motivated by the “Central European Space,” should move to the level of a continental state on the global scale at the territorial expense of the “older peoples”—the French and English. Yet, the ideological aspect of geopolitical confrontations was considered by Kjellen to be secondary to the spatial aspect.

2.3 Towards the Concept of Middle Europe

Although Swedish himself, Kjellen pressed for political rapprochement between Germany and Sweden. His own geopolitical representation on the importance of the unification of German space matches exactly the theory of “Middle Europe” (Mitteleuropa), developed by Friedrich Naumann.

In his book “Mitteleuropa” (1915), Naumann gave a geopolitical diagnosis that matches exactly with the concepts of Rudolf Kjellen. From Naumann’s point of view, to withstand competition from such organized geopolitical formations like England (and its colonies), the USA, and Russia, the peoples inhabiting Central Europe should unify and organize in new integrative, political-economic ways in this space. The axis of this space, would of course, naturally, be Germany.

In his book “Mitteleuropa” (1915), Naumann gave a geopolitical diagnosis that matches exactly with the concepts of Rudolf Kjellen. From Naumann’s point of view, to withstand competition from such organized geopolitical formations like England (and its colonies), the USA, and Russia, the peoples inhabiting Central Europe should unify and organize in new integrative, political-economic ways in this space. The axis of this space, would of course, naturally, be Germany.

Mitteleuropa differed from pure “Pan-Germanic” projects, since it was not based on nationalism, but strict geopolitical understanding, which the basic meaning was not given to ethnic unity, but commonalities in geographical fates. Naumann’s project involved the integration of Germany, Austria, the Lower Danube states, and in the wider view—France.

The geopolitical project was also supported by cultural parallels. Germany itself was the organic formation identified with spiritual notion of “mitellage,” the middle position. This was more deeply formulated in 1818 by Ernst Arndt: “God has situated us in the center of Europe: We (the Germans) are the heart of our part of the world.”

Ratzel’s ideas gradually acquired tangible traits through Kjellen and Naumann’s “Continental” theory.

00:58 Publié dans Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : rudolf kjellen, géopolitique, friedrich naumann, mitteleuropa, europe centrale, europe |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook