Notes on Céline’s Castle to Castle (D’un Chateau L’autre)

Today is the birthday of novelist Louis-Ferdinand Destouches (May 27, 1894–July 1, 1961), a French physician who wrote autobiographical fiction and political propaganda under the pen name Louis-Ferdinand Céline.

Like Ernest Hemingway (who died the day after Céline), Céline is arguably more intriguing for his wayward, adventurous life than for his books. Both were stylistic innovators, but that has a downside: yesteryear’s innovation tends to become today’s annoyance. Affected or eccentric prose tends to thwart rather than aid a reader’s comprehension. Hemingway of course had his minimalist, mannered sentence construction (which he imagined to be the prose equivalent of Matisse or Picasso’s painting technique). Céline’s usual idiom was something a little more daunting—a staccato, stream-of-consciousness rant. Page after page of word-pictures and asides, each separated by a three-dot ellipsis, rather like an old-time Browadway columnist…

Frankly, just between you and me, I’m ending up even worse than I started . . . yes, my beginnings weren’t so hot . . . I was born, I repeat, in Courbevoie, Seine . . . I’m repeating it for the thousandth time . . . after a great many round trips I’m ending very badly . . . old age, you’ll say . . . yes, old age, that’s a fact . . . at sixty-three and then some, it’s hard to break in again . . . to build up a new practice . . . no matter where . . . I forgot to tell you . . . I’m a doctor . . . [1]

That’s the beginning of D’un Chateau L’autre, or Castle to Castle (1957), Celine’s ever-so-slightly fictionalized account of his adventures during and after the last months of the Second World War. It’s a good example of Celine’s delivery throughout the book, with endless repetitions and self-contradictions. Addressing himself to his legion of fans, he here apologizes for telling them what they already know—that he was born in Courbevoie—then goes on and informs them, as though for the first time, that he’s a physician!

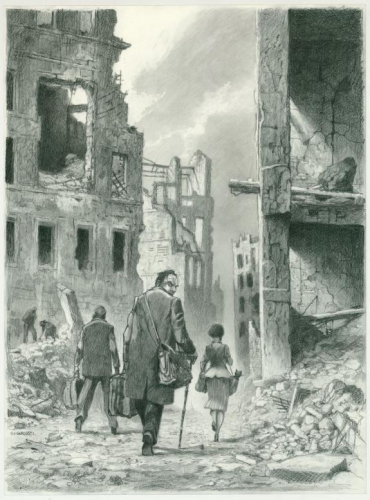

The heart of the “novel” is famously set in Sigmaringen, the ancient Hohenzollern castle-town on the Danube, just north of Lake Constance. This is where about 1400 French collaborators and Vichy officials found refuge from mid-1944 till May 1945. Celine’s account of Sigmaringen is by far the most grotesque, blackly satirical section of his book—full of overflowing toilets, starving babies, hysterical crowds, ceaseless air-raids; and with appearances by Petain, Laval, and Fernand de Brinon (Celine’s fellow collabo writer, Vichy Secretary of State, and now head of the government-in-exile).

The heart of the “novel” is famously set in Sigmaringen, the ancient Hohenzollern castle-town on the Danube, just north of Lake Constance. This is where about 1400 French collaborators and Vichy officials found refuge from mid-1944 till May 1945. Celine’s account of Sigmaringen is by far the most grotesque, blackly satirical section of his book—full of overflowing toilets, starving babies, hysterical crowds, ceaseless air-raids; and with appearances by Petain, Laval, and Fernand de Brinon (Celine’s fellow collabo writer, Vichy Secretary of State, and now head of the government-in-exile).

But nothing in Celine is ever straightforward; his style always gets in the way. In order to get to this historically informative part of the narrative we must first peel away, artichoke-like, about 100 leaves of dream-like recollections as the author’s mind wanders back from the present (1950s) to his six-year postwar imprisonment in Copenhagen, where he appears to have split his time between months in a hospital ward, suffering from cancer and pellagra, and episodes of solitary confinement. The Danish (for apparently they were) officials drag him out at intervals, trying to browbeat into making the preposterous admission that he had supplied the Germans with the secret plans of the Maginot Line.

A few flashbacks of Sigmaringen appear briefly as we dig through the memory-artichoke: how the Vichy officials came to consult him toward the end in early 1945, asking the good doctor what’s the best way to commit suicide. Céline smugly notes that Laval was too proud to ask for advice, as he was already prepared for the endgame. But it turned out that Laval’s cyanide capsule was old and spoiled by moisture by the time he attempted to use it, so Laval didn’t get to cheat the firing squad in late 1945 (p. 32).

One day in 1950s Paris, the narrator encounters an old collabo actor friend, “Le Vigan,” returned to France in disguise, with wife and pet cockatoo, outfitted in outlandish costume and posing as the pilot of an ancient bateau-mouche in the Seine. Le Vigan had been at Sigmaringen with Céline. Overjoyed to see each other, they reminisce about old times.

This is Céline’s “madeleine” moment. His thoughts finally spiral backwards to his months at the Castle.

Maybe I shouldn’t talk Siegmaringen [sic] up…but what a picturesque spot…you’d think you were in an operetta…a perfect setting…you’re waiting for the sopranos…the lyric tenors…for echoes you’ve got the whole forest…ten, twenty mountains of trees! Black Forest, descending pine trees…waterfalls…your stage is the city, so pretty-pretty, pink and green, semi-pistachio, assorted pastry, cabarets, hotels, shops, all lopsided for the effect…all in the “Baroque boche” and “White Horse Inn” style…you can already hear the orchestra…the most amazing is the Castle…stucco and papier-mache…like a wedding cake on top of the town…

Yet not was all pretty-pretty and operetta-like:

In our time, I’ve got to admit, the place was gloomy…tourists, sure…but a special kind…too much scabies, too little bread, and too much R.A.F. overhead…and [Gen.] LeClerc’s army right near…coming closer…the Senegalese with their chop-chops…for our heads… (p. 126)

Céline has access to the Castle ex officiobecause he is a physician, but he spends much of his time tending to the women and children of the collabos and the French miliciens, roughly interned in a nearby camp where they are slowly being starved to death on a diet of “raw carrot soup.”1,142 is the number Celine gives for collaborators living in the Castle and in nearby hostelries. (Historians give the number as about 1,400.) The collabos spend much of their time wondering what their fate would be when the war is over. They think about Napoleon’s friends and partisans when the Emperor was finally exiled to St. Helena. Adolfins, Céline humorously imagines, is what the leftist press in France will call the Vichyites and collabos.

The attitude of the local Germans, he says, is not at all friendly:

…the real hatred of the Germans, I might say in passing, was directed against the “collaborators”…not so much against the Jews, who were so powerful in London and New York…or against the Fifis [Free French], who were supposed to be “the Vrance of tomorrow”…pure and sure…but against the “collabos,” the dregs of the universe, who were there at their mercy, really weak and helpless, and their kids who were even weaker…let me tell you: the Nuremberg trials need doing over! (p.131)

One day there is a rumor that there will be a distribution of free bread—maybe bread and sausage—over by the Castle drawbridge. A thousand people gather, looking filthy and lousy, to the wonderment of the German guards nearby, who have heard no such rumor. The crowd waits in anticipation for a half-hour, an hour . . . and finally there is activity at the Castle gate. But it is only Pétain and entourage, going out for the daily stroll!

One day there is a rumor that there will be a distribution of free bread—maybe bread and sausage—over by the Castle drawbridge. A thousand people gather, looking filthy and lousy, to the wonderment of the German guards nearby, who have heard no such rumor. The crowd waits in anticipation for a half-hour, an hour . . . and finally there is activity at the Castle gate. But it is only Pétain and entourage, going out for the daily stroll!

Céline has only contempt for Le Maréchal and his luxe life, marvels at the crowd’s docility when they see Pétain hasn’t emerged to give them bread.

…he didn’t leave a crumb for anybody!…housed like a king!… [. . .] a whole floor to himself…heated!…with four meals a day…sixteen [food] cards plus presents from the Fuehrer, coffee, cologne, silk shirts…a regiment of cops at his beck and call…a staff general…four cars…

You would have expected that crowd of roughnecks to do something…to jump him…to disembowel him…not at all…just a few sighs…they step aside…they watch him start on his outing… [. . .] men and women…little girls’ curtseys…the Marshall’s walk…but not bread, no sausage. (p. 148)

There is an air raid. For some reason the Castle has never been attacked, but there is a rumored explanation for this too: it is being reserved for Gen. Leclerc when he finally comes through…

…he was already in Strasbourg, with his Fifis and his coons…you could tell by the people coming our way…refugees with their eyes popping out…the things they’d seen…the wholesale decapitations with the chop-chop…Leclerc’s Senegalese…rivers of blood. The gutters full of it. (p. 152)

Pétain and entourage return abruptly as the RAF raid crescendoes, taking shelter under a railway bridge arch. No more is heard about the bread ration.

Celine and his wife go back to their room in the town down the hill, No. 11 Hotel Löwen, where the stench is horrendous because of the single public toilet constantly overflowing in the upstairs lobby:

…so you can imagine our lobby…the cursing and farting of the people who couldn’t hold it in…and the smell…the bowl, overflowed!…what can you expect? It was always plugged…people went in three…four at a time…men, women, children…every which way…they had to be dragged out by the feet…by raw force…hogging the crapper… (p.162)

Much of this is undoubtedly hyperbole, disgust turned into black humor to make it palatable (so to speak). Rivers of urine and excrement flowing down the hotel stairway, Céline claims!

It was a special point with him. He was not only a physician horrified by medical filth (his first book was a dissertation on hospital sepsis), so we can allow him literary license in this quasi-novel. But then his fancy takes him a little bit too far, and we fully realize he’s giving us crazy-talk to express the craziness of the time and place…

Opening the door to his shabby room at the Hotel Löwen, Céline finds that his bed is now occupied by an insane man being straddled by an equally insane fellow dressed as a surgeon:

…well anyway a man in a white smock getting ready to operate on him… forcibly!…three, four scalpels in hand…head-mirror, compressor, forceps!…no possible doubt!

“Doctor! Doctor! save me!”

“From what? From what?”

“It’s you I came to see, Doctor! The Senegalese! The Senegalese!”

“What about them?”

“They’ve cut everyone’s head off.”

“But he’s not a Senegalese.”

“He’s starting with the ear!…it’s you I wanted to see, Doctor!”

“But he’s not a Senegalese, is he?”

“No…no…he’s a lunatic!”

(pp. 164-65)

Just another day in Céline’s Sigmaringen.

Note

1. All quotations are taken from the Ralph Manheim translation of Castle to Castle, first published in 1968 by Dell Publishing Co.

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg