There has been much talk of Japan recently, which has significantly intensified its foreign policy: Japan is working together with the United States to promote the Indo-Pacific strategy with multilateral support within the framework of the US-Japan-India-Australia quadrilateral security dialogue (QUAD), which involves strengthening the Japan Self-Defense Forces and intensive peace treaty negotiations with Russia.

It is a well-known fact that one of the aims of a country’s foreign policy is to ensure the state experiences progressive internal social and economic development. For Japan’s high-tech and industrialized economy, which does not have enough of its own national energy resources to satisfy all its energy needs, one of the most important preconditions for economic growth is to secure an uninterrupted imported energy supply. However, to succeed in solving this problem, it is necessary to highlight two key factors here: a sufficient supply and a competitive price. Let’s try to gain an insight into what the Japanese economy needs in terms of energy resources and where the supply comes from.

Although Japan’s total area exceeds 370 thousand square kilometers; today, the county does not have enough natural resources to meet its own energy needs. This is largely linked to the aggressive exploitation of natural resources which took place in the past, which you can get a good sense of by looking at a map of all the mining enterprises which used to operate in Japan, along with all the oil and gas fields.

Japan is the world’s third largest oil consumer, second only to the US and China. The Japanese consume about two billion barrels of oil a year, 99.7 percent of which is imported. Tokyo weighs in heavy on imports in world rankings, bypassing Beijing to take second place. A significant risk factor threatening Japan’s oil supply is the conflict in the Middle East — violent, simmering flare-ups which could boil over — as Japan sources more than 86 percent of all its imported oil from the region (Saudi Arabia – 31.1%, UAE – 25.4%, Qatar – 10.2%, Iran – 11.5%, Kuwait – 8.2%).

Therefore, it is no wonder that the Japanese authorities are anxiously monitoring the situation in the Asia Pacific gas market. China is the leading buyer of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the Asia Pacific, whose demands for “blue fuel” are only set to grow.

Not too long ago, Japan even made an attempt to strengthen its position in this market by importing gas from Russia. Japanese companies have developed a project to build a gas pipeline from Sakhalin, with a capacity of 20 billion cubic meters per year. Taking Japan’s current gas consumption of 123 billion cubic meters, if this gas pipeline was constructed, Tokyo would be able to meet a sixth of the national demand for this type of fuel. In 2014 however, Japan imposed sanctions against Russia “for Crimea,” and abandoned the project, even though it could significantly improve the island state’s vulnerable situation as an energy importer.

As a result, Tokyo now has no other choice but to compete with other Asia Pacific countries to secure its LNG supply, which increases the cost of energy and leaves the Japanese with no guarantee of a sufficient supply.

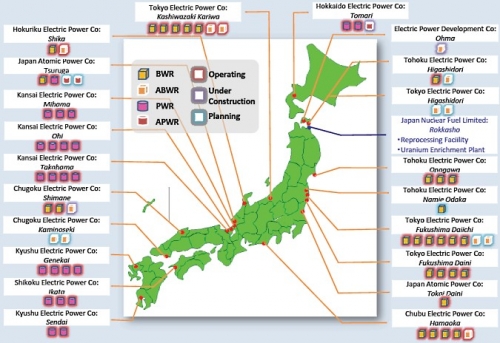

Although Japan does have some of its own coal reserves, it is the world’s top LNG importer. In 2017, Japan spent $ 23 billion to purchase 209 million tons of natural gas About 18 percent of the world’s coal supply goes to Japan. Along with imports of metallurgical coal for the steel industry, Japan is increasing its thermal coal imports. This is due to an electricity shortage caused by the nuclear power plants being shutdown, which had still been operating up until that point. Against this backdrop, the outlook for the next few decades is that the Japanese will be using coal, primarily for electricity production at dozens of new thermal power plants.

The given data on Japan’s oil, gas and coal imports highlights Tokyo’s almost total dependence on imported energy supplies. The availability of this imported energy supply is largely determined by the stability / instability in the region where it is produced, primarily in the Middle East, as well as in the regions along the pipeline routes, where China’s influence is growing. Energy prices today are among the highest they have ever been, as the growing Asia Pacific market consumes more and more energy each year.

Under the given circumstances, one of the most cost-effective ways to strengthen Japan’s energy security in economic terms is greater cooperation with Russia, which possesses and is capable of exporting the full spectrum of energy resources which Tokyo needs. The shared border between Russia and Japan also guarantees that the energy supply will not be severed along the way.

The conclusion this article would give is that Japan’s over-dependence on Washington, as well as the absence of a peace treaty with Moscow act as barriers which frustrate efforts to increase cooperation between Japan and Russia in the area of energy supply (direct supply and transit through other states). The influence of the first factor, Japan’s over-dependence on the US, is apparent in the support Japan expresses for the US policy of levying sanctions against Russia, even in cases and circumstances when this contradicts Japanese interests by not only frustrating bilateral cooperation between Japan and Russia, but also by going against the basic interests of Japan’s national security. The second factor is the peace treaty. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s government is busily working to try and find a solution, but the approach they are taking is not geared towards a win-win treaty.

It is clear that Japan’s ambitions to make a return to the big geopolitical game are suppressed by Tokyo’s dependence on energy imports. As it happens, Germany makes a good example of a state in a similar situation as one of Europe’s most powerful economies and major energy consumer and importer. Berlin is aware of how critically important it is to ensure a cost-effective supply of natural gas to fuel the “locomotive of the European economy”, and is currently implementing its Nord Stream 2 project to lay a gas pipeline along the bottom of the Baltic Sea, despite strong opposition from Washington.

Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that Tokyo will look at the experience Berlin has had and follow suit in the near future, and that without walking around Washington on eggshells any longer, Japan will begin to look after its own interests and develop bilateral relations with Russia which are beneficial for both countries.

Valery Matveev, economic observer, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook.”

https://journal-neo.org/2019/04/29/japan-s-political-ambi...

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg