dimanche, 08 mars 2009

When American Imperialism chased Spain out of Cuba

When American Imperialism chased Spain out of Cuba

by Philippe Conrad

A century ago, in 1898, the Cuban war broke out against Spain. It was an American war that was «altruistic and moral». Through this war, which called on the resources of misinformation and brainwashing, the United States began its career as a world power.

«All is quiet here; there are no problems and there’ll be no war, I want to come back»…«Stay where you are please and send us pictures, I am responsible for preparing the war…» This exchange of telegrams between Frederic Remington, the reporter-artist of the New York Journal, and his boss, William Randolph Hearst, on the eve of the Spanish-American conflict of 1898, just about sums up the situation at the moment. It shows the part that the manipulation of American public opinion played in unleashing this war. We shall have to wait until the First World War before governments, those of the Anglo-Saxon countries in the first place, have recourse on a such a grand scale to these propaganda tricks. But the stakes were considerable, for it was a question of chasing Europe – or more precisely a Spain that was only a shadow of its former self – from the American hemisphere in order to perfect the hegemony of the United States over the New World as a whole.

The right to possession of the world

America’s designs on Cuba and on the Caribbean sea simply and quite naturally completed the geopolitical grand design which was to make the new state into a continental power, opening onto the two oceans and able to impose its domination over the whole western hemisphere. These designs were clear even in the 1820s when John Quincy Adams considered that Cuba was the key to the Caribbean and that its proximity to Florida and the mouth of the Mississippi would one day make it necessary, «through the simple law of political gravitation», for America to seize it. What held Washington back at that time was fear of English reaction, for London might worry about the fate in store for Jamaica. For American officials, it was better to be patient and leave Cuba in the hands of an enfeebled Spain rather than engage in an action likely to justify British opposition. It was enough to wait for the right moment or for circumstances to appear most favourable for the realisation of what John Fiske called, in 1885, the «manifest destiny» of the United States.

In those last years of the century, projects for driving a canal through the Central American isthmus at Nicaragua or Panama gave new life to the already old desires of the Washington government. Several theorists at that time justified America’s ambitions, and in their wake their formed in Congress a whole «imperialist» clan demanding a foreign policy in keeping with the industrial dynamism which was making of the USA a world economic power. In 1885, Pastor Joshua Strong wrote Our country in which he exalted «the superiority of the Anglo-Saxon race». Five years later, John W Burgess, professor of political sciences at the University of Columbia, insisted on the rights possessed by the Anglo-Saxons to world dominion: «Their mission is to lead political civilisation in the modern world and to bring this civilisation to the barbarous races […] since it is in the interest of world civilisation that law, order and true liberty, which is its corollary, should reign throughout the world…» That same year, Admiral T Mahan published his book The influence of Sea Power upon History, which foretells an impressive rise in the strength of America’s naval power. The United States must take control of the Caribbean Sea and of the future canal that will join the Atlantic to the Pacific. They must also push their expansion into the Pacific, notably into the Hawaiian archipelago. Under the presidency of the republican Benjamin Harrison (1889-1893), the secretary of State James Blaine was preparing the way for these various projects, but the election of the democrat Stephen G Cleveland seems to have put a stop to them, at least temporarily. However, his republican opponents were not put off, and Henry Cabot Lodge, the naval commission’s spokesman at the House of representatives, made a speech in 1895, wherein he claimed Cuba and the Hawaiian islands for the United States. There thus came into being a thoroughgoing «imperialist» movement inspired by that «jingoism» which, at the same period, lay behind the politics of a Joseph Chamberlain in England.

At the heart of this movement, the young Theodore Roosevelt was already there, writing to Cabot Lodge, his mentor in politics, that «the country needs a war». The elections in 1897, which bring the republican William Mac Kinley to power, enable the young Roosevelt to become Under-Secretary of State for the Navy, in 1897. Two months later, he explained to the officer cadets at the Naval College «that the diplomat must be the servant and not the master of the soldier». In November of the same year, he wrote to a naval officer to say that he hoped for a war against Spain «to aid the Cubans in a humanitarian concern». But above all «to guarantee complete liberty for America from European domination… This war will be a great lesson, and we shall profit greatly from it». In December 1897, when commercial circles and the economic press were showing their opposition to a war for Cuba, the hot-headed under-secretary of State affirmed that «we shall have this war for the liberty of Cuba despite the timidity of commercial interests…»

Press campaigns and sending of weapons

The United States had already offered on several occasions since 1843 to buy from Spain the main island of the Caribbean, but each time the government of Madrid had amiably turned down these offers. In 1850, therefore, the American administration encouraged the installation in New York of a Cuban council favourable to the island’s independence, and from 1865 Washington supported these rebels by supplying them with arms and money. Between 1868 and 1878, the first war of independence came to nothing. The United States’ interest in the island did not wane, however, for it was they who bought nearly all the sugar exported from the island, and American capital investments in this market amounted to fifty million dollars of the island’s economy. Founded in 1892, José Martí’s Cuban revolutionary party was supported financially by Edwin F Atkins, the American sugar «king».

When a fresh insurrection broke out on the island in February 1895, the democrat president Cleveland and his Secretary of State Bryan had no wish to intervene directly. The death of Martí, killed in the fighting in May, did not put an end to the rebellion. The North American press then undertook to set public opinion against Spain. It sounded off against the death of several Cuban revolutionaries, denounced the fact that American citizens were in jail on the island, and exalted the courage of Evangelina Cisneros, the daughter of a rebel leader, whom W R Hearst had removed from Cuba so that she might be given a triumphant welcome in New York… It finally published a false letter from Dupuy de Lôme, the Spanish ambassador to Washington, in which Mac Kinley was presented as a «low level politician». During that time, from June 1895 to May 1897, forty-two naval convoys brought arms to the insurgents from the American coasts.

On the island itself, however, Spain’s new representative, General Blanco, succeeded in forming a government by uniting the reformists and autonomists, but excluding those in favour of independence who were supported by the USA. It was a few days later, following the riots in Havana, that the battleship Maine entered the port, on a «courtesy» visit.

It is now known very precisely that the decision to go to war against Spain, if she persisted in her refusal to sell Cuba, was taken in 1896. A recent military history congress, held in March 1998, has revealed the detail of the plans prepared for this eventuality. The scenario was then written down. On 25 January 1898, the battleship Maine, therefore, entered the port of Havana, followed fifteen days later by the cruiser Montgomery which had just laid anchor in the port of Matanzas. Three weeks later, on 15 February, the accidental explosion of a submarine mine sank the Maine in the port of Havana. Two hundred and sixty American sailors were killed in the explosion, which everyone now recognises as having been purely accidental, and some even think it was plainly provoked by the Americans (it is interesting to note that no officer was among the victims; they were all at a reception in the town). The official American report is no less accusatory of Spain. Madrid proposed entrusting the enquiry to a mixed commission, but Washington refused. The Spanish government then turned towards its European counterparts and solicited the arbitration of Pope Leo XIII, but obtained nothing, even though it accepted the immediate armistice imposed by Mac Kinley on 10 April. The American senate will soon vote for the necessary funding for «an altruistic and moral war which will bring about the liberation of Cuba», and war was declared on 24 April. A «splendid little war» for the Secretary of State John Hay, a war which rekindled that led by Spain against the Cuban rebels, a conflict which, according to General Blanco «would have come to an end, had it not been for American malevolence».

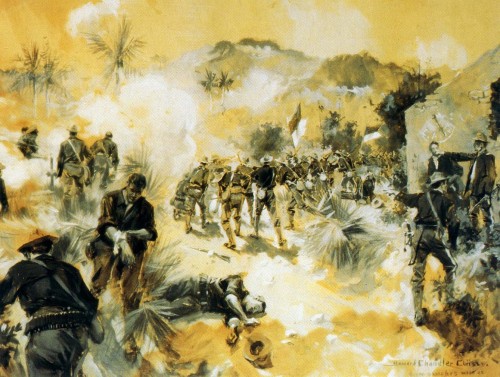

It was in the Philippines that the Americans struck their first blows since Admiral Dewey destroyed Admiral Montojo’s fleet in the harbour of Manila, outside Cavite. The conquest of Porto Rico was a military walkover and, at Cuba, Admiral Cervera’s fleet was totally outstripped on the technical level by the American ships, and destroyed on 3 July outside Santiago. Fifteen thousand Americans landed at the end of the month of June, but still Colonel Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders had to put up a furious fight against the troops of Generals Linares and Vara del Rey, on 16 July, and overcame the defences of the hill of San Juan. In coming to take part in the battle himself, Roosevelt put his deeds in line with his words. On 17 July, Santiago de Cuba capitulated. On 12 August, through French mediation, an armistice was concluded prior to peace negotiations which ended in the Treaty of Paris, signed on the following 10 December.

Spain was made to abandon all sovereignty over Cuba, she also lost Puerto Rico and had to yield the Philippines and Guam to the USA for twenty million dollars. A little later, she also had to cede to the conqueror – who had seized the Hawaiian Islands during the month of August – those of the Mariannas, the Carolinas and the Palaos. It was a peace that seemed like a second death of the Spanish Empire and which opened the way to a spectacular rise in the power of the United States. Theodore Roosevelt will be able to wave his big stick in the Caribbean. Cuba, San Domingo, Nicaragua and the Panama, separated from Columbia in 1903, will become American quasi-protectorates. Once annexed, the Philippines will become the theatre of a revolt, which will last four years at a cost of five thousand dead to the new occupants. Cuba will endure a four-year military occupation, and it is only after accepting a treaty placing her in a state of total subjection to Washington that the island will be able to have its «sovereignty» recognised. The «corollary» is Roosevelt with his Monroe doctrine henceforth reserving the right of the United States to intervene in the affairs of neighbouring countries if deemed necessary for the re-establishment of order. Senator Beaveridge, from Indiana, can now consider that «God has not prepared the peoples of English and Teutonic tongue over a thousand years simply for them to admire themselves vainly and passively. No, he made us to be the organising masters of the world in order to establish order where chaos reigns. He has given us the spirit of progress in order to conquer the forces of reaction throughout the whole world. He has placed within us the gift of governing so that we may give government to savage and senile peoples. Without such a force, the world would relapse into barbarity and the night. And of all our race, he has designated the American people as his chosen nation to begin the regeneration of the world.»

To justify intervention, all means are good!

Arnaud Imatz

Certain papers of the New York press played a decisive role in preparing public opinion to accept American intervention in Cuba. The main papers here were the New York Journal, bought by William Randolph Hearst in 1895 and the World, owned by Joseph Pulitzer, to which we should add the Sun and the Herald. This press cultivated sensationalism to the point of practising a veritable disinformation campaign as a way of «advancing the event». […]

For this popular press, avid for spectacular events likely to appeal to the imagination of the masses, Cuba will provide particularly rich material. A most rudimentary kind of manichaeism thus presents the Spaniards as uncouth and sadistic brutes, representatives of a backward country, subjects of an anachronistic and corrupt monarchy. They were attributed with every kind of crime and atrocity, which happily completed the «black legend» developed by Anglo-Saxon historiography regarding the conquest of America by the subjects of Charles V and of Philippe II. It was a very useful way for the Anglo-Saxon colonisers of North America to have their own treatment of the Indians forgotten. Terror, violence and famine were the rule in Cuba for a press all too content to reproduce the communiqués from the Junta Cubana, the council of exiles installed in New York. The «testimonies» of victims filled up entirely fabricated dossiers, containing detailed accounts of Spanish depravity. […]

The reassembling and regrouping of whole populations into camps led to a heavy mortality rate among the prisoners, as a result of epidemics, which also struck the Spanish soldiers. But Hearst and his journalists did not skimp over the figures. Six hundred thousand dead, not one less, more or less one third of the island’s population, in other words a veritable genocide before the word was coined. In fact, the most serious studies undertaken by American research workers in the course of the following decades have revealed that human losses for the period 1895-1898, including the Spanish victims, did not exceed the number one hundred thousand. The lie was exposed with the publication in 1932 of a work initiated by the Baton Rouge University in Louisiana, called Public Opinion and the Spanish-American War. A study in war propaganda. None of which was of much importance forty or so years later. By blowing American popular opinion white hot, by exploiting the false letter from Ambassador Dupuy de Lôme, by giving credit to the myth of an attack responsible for the explosion of the Maine, Hearst and Pulitzer had played their part and made it possible to justify America’s control over Cuba.

00:05 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : géopolitique, etats-unis, cuba, espagne, amérique latine, amérique du sud, amérique, impérialisme, génocide, crimes de guerre |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les commentaires sont fermés.