mardi, 23 septembre 2014

Naoko Inose’s Persona: A Biography of Yukio Mishima

Naoko Inose’s Persona: A Biography of Yukio Mishima

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

Naoko Inose

Persona: A Biography of Yukio Mishima [2]

Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 2013

Editor’s Note:

This is a review of the Japanese edition of Persona, which is available now in English translation. I have read the translation, which appears to be much longer (864 pages) than the Japanese original. It is a treasure trove of information on Mishima. As an aside, the book’s unselfconscious frankness about sex and meticulous cataloging of genealogy and rank give one a sense of the consciousness of pre-Christian European society.

The Japanese version of Persona was originally published in November 1995 by Bungei Shunshu (literally meaning “the Literary Spring and Autumn”), an established and prestigious publishing house in Japan. The author, Mr. Naoki Inose, is a maverick and contentious figure who served as the vice governor of Tokyo municipality for a long time while also being a highly prolific and popular writer, having penned no less than 30 books so far, mostly on political, historical, and cultural themes. He was lately in hot water, being forced to step down from his official post due to alleged involvement in a murky financial scandal. His political and administrative stance, by post-war Japanese standards, is mainstream conservatism (center-Right).

The main body of the book has about 390 pages, including a prologue, four chapters, and an epilogue. There is also a brief postscript and an extensive bibliography which together occupy another nine pages. Considering the length of the book, it is surprising that there are only four chapters. The 17-page Prologue is a novel-like start, the main character of which is a former schoolmate of Yukio Mishima, and whose father also happened to be an old acquaintance and old schoolmate of Mishima’s father Azusa Hiraoka (Hiraoka is the real family name of Mishima), both pursuing the careers of elite imperial government officials, but with quite different fates. The author’s intention in starting the book in this way was to highlight Mishima’s family background so as to shed light on the factors, both familial and historical, that shaped and molded the early development of Mishima’s quite unorthodox and eccentric personality.

Indeed, the author goes far further than most would expect, expatiating on the overall political and social picture of Japan in the late Meiji and early Taisho periods at the very beginning of the 20th century, which, in the author’s presumed reckoning, might better disclose and clarify the political, socio-cultural, and family backdrops of Mishima’s childhood, which was characterized by a mixture of docile and rebellious elements. The first chapter, called “The Mystery of the Assassination of Takashi Hara,” lasts almost 80 pages. Here the author talks about the historical background of the time in which Mishima’s grandfather Sadataro Hiraoka saw his career blossom then wither due to larger and uncontrollable political struggles.

Sadataro was a capable functionary favored and appointed by then the Internal Minister and later the Prime Minister of Japan Takashi Hara, nicknamed the “Commoner Prime Minister,” to be the governor of Karabuto (the Southern half of the Sakhalin Island, ceded to Japan by treaty after the Russo-Japanese War of 1905 and forcibly annexed by Soviet Union at the end of WWII). However, due to some suspicious financial dealing and mishaps which were seized by political foes to attack him, and political sectarian conflicts during the Hara administration and after his assassination, Sadataro was relieved of his governorship, and from then on, Mishima’s family’s fortune started to take an abrupt and sharp downturn.

The second chapter, “The Insulated Childhood,” shifts attention from the rise and fall of the Hiraokas to Mishima himself. Mr. Inose spends 90 pages on Mishima’s complex and seeming contradictory childhood, using narration interspersed by flashbacks, and talks about the family life of the Hiraokas, the inter-relationship of family members, religion, Mishima’s grandparents and parents, especially his fastidious and arbitrary grandmother and his bemused father, against the background of decline of the family’s fortunes as a result of political failures of his grandfather. The author devotes large passages to explaining such matters as Mishima’s poor physical health, his tender, timid, and self-isolating personality as a child molded by the uncannily tense family ambience, and his father’s desperate last-ditch effort that brought about his narrow escape from the military draft in his late teen years near the end of the Second World War.

In this chapter, the author also starts to introduce Mishima’s passion for literature, which developed quite early, and his first attempts at writing, as well as his friendship and literary exchanges with several likeminded youths who gave him encouragement and inspiration. One point meriting emphasis is the influence of Zenmei Hasuda, a young imperial army officer, a steadfast traditionalist and nationalist, and a talented writer who killed a senior officer for cursing the Emperor and then committed suicide near the end of the war.

In the third chapter, that lasts almost 100 pages, the author continues to elaborate on the young Mishima’s literary and private life, culminating in his crowning literary achievement, the novel Kinkakuji translated as The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, which the author rightfully perceives as a landmark of the first phase of Mishima’s literary life, which is characterized by richly colored, minutely detailed, and often unsettling depictions of the inner lives of men among the ruins of post-war Japan — a formerly proud nation wallowing in nihilism.

It is noteworthy that Mishima’s works at this stage are rather different from the second stage of his literary activities, in which his works display a clearly nationalist and Rightist perspective. While Mishima’s exquisite writing reached its peak (or near peak) quite early in his life, his understanding of and awakening to the Japanese identity and nationalism centered on the monarchist tradition underwent a gradual process of maturation and was still immature and inchoate at his first literary stage, i.e. the time around his writing of Kinkakuji and other non-nationalist works, in contrast to his second literary phase of more virile, robust, and nationalistic works from Sun and Steel to The Sea of Fertility. In addition, Mishima’s dandyesque personal life of drinking, socializing, and mingling with fashion-conscious rich girls as described in this chapter was also indicative of his less than mature literature and personality at his stage of his life.

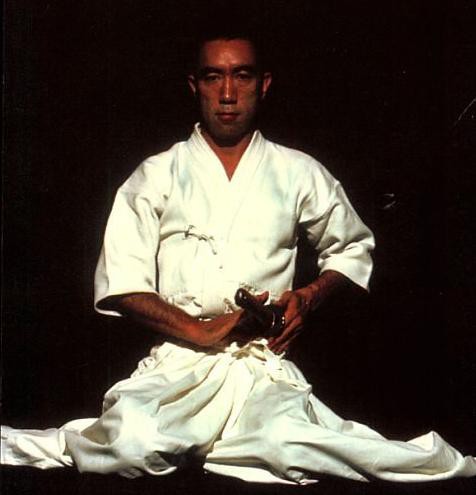

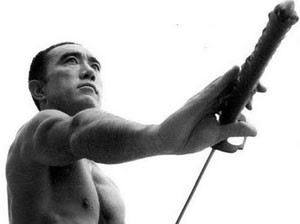

Chapter four, being the longest of the four chapters at about 110 pages, stands out as a relatively independent account of Mishima’s later years, dealing with both literature and political/ideological developments, leading to his failed coup, featuring his impassioned exhortation to the military servicemen and his ritual suicide by seppuku. This part covers the Mishima most familiar and interesting to Western readers. The chapter covers his body-building practices, his continued literary endeavors, consummated by the masterpiece The Sea of Fertility,his nominations for the Nobel Prize for Literature, and his increasingly active socio-political undertakings, including organizing his private militia troop, the Tatenokai (Shield Society), his serious and strenuous military training in Jieitai (Self-Defense Force), the post-war Japanese military — with the rather naïve aim of safeguarding the Emperor in concerted effort with the military in case of domestic unrest or even sedition at the hands of the leftist or communist radicals — and the events of this final day, November 25, 1970.

Chapter four, being the longest of the four chapters at about 110 pages, stands out as a relatively independent account of Mishima’s later years, dealing with both literature and political/ideological developments, leading to his failed coup, featuring his impassioned exhortation to the military servicemen and his ritual suicide by seppuku. This part covers the Mishima most familiar and interesting to Western readers. The chapter covers his body-building practices, his continued literary endeavors, consummated by the masterpiece The Sea of Fertility,his nominations for the Nobel Prize for Literature, and his increasingly active socio-political undertakings, including organizing his private militia troop, the Tatenokai (Shield Society), his serious and strenuous military training in Jieitai (Self-Defense Force), the post-war Japanese military — with the rather naïve aim of safeguarding the Emperor in concerted effort with the military in case of domestic unrest or even sedition at the hands of the leftist or communist radicals — and the events of this final day, November 25, 1970.

Although Persona has an overly long and detailed discussion of Mishima’s family history, the book still flows and proves an engaging read on the whole. The last chapter, though a bit overshadowed by the three preceding chapters, is definitely the most pertinent and fascinating of the whole, filled with interesting facts with insightful and trenchant observations.

Mishima’s veneration of the Emperor (Tenno) and ultimately the Imperial bloodline (Kotoh) of Japan, his candid criticism of Emperor Hirohito, and his final urge toward the coup and the subsequent suicide were already implied in his Kinkakuji, albeit symbolically as the impregnable top floor of the Kinkakuji pavilion itself. These themes became explicit in Voice of the Spirits of Martyrs published in 1966, which especially demonstrates Mishima’s mixed feelings if not overtly bitter resentment of Hirohito for his ignoble role in the failed Ni-Ni-Roku (Feb. 26) Coup of 1936[1] and his abject “I-am-a-human-not-a-god” announcement in 1945.[2] In the book, Mishima speaks through the mouth of a 23-year-old blind man, giving voice to the spirits of the Ni-Ni-Roku rebels and the Kamikaze pilots, i.e., the spirits of martyrs, speaking of the post-war economic boom coupled with the moral decay of Japanese society:

Under the benevolent imperial reign, the society brims with peace and stability. People smile albeit not without conflicts of interest and confusion of friends and foes. Foreign money drives and goads people, and pseudo-humanism becomes a necessity for making a living. The world is shrouded in hypocrisy while physical force and manual labor are despised. Youthful generations feel suffocated by torpor, sloth, drugs, and meaningless fights, yet they all move along the prearranged path of mundanity like meek sheep. People think about making money, even small amounts, for which they degrade their own value. Private cars multiply, whose stupid high speed renders people soulless. Tall buildings mushroom while the righteous cause and moral principles collapse, and the glittering glass windows of those buildings are just like fluorescent lights of implacable desires. Eagles flying high in the sky and break their wings, and the immortal glories are sneered at and derided by termites. In such a time, the Emperor has become a human.[3]

According to Mishima, the daily routines under the rapid economic growth of 1960s is but an ugly and hollow sign of happiness, all attributable to the fact that the Emperor Hirohito has proclaimed himself no longer a divine figure, a sacrosanct “Arahitogami”[4] but a mere human being devoid of sanctity. Mishima expressed this view via the collective voice of the spirits of the martyrs, that the Emperor has assumed a duality of image, one being the last sacred embodiment of the national myth, and the other being one kind smiling grandfather presiding over the economic rationalism of the current age, and it is the latter, the protector of the daily routines of the post-war Japan, that Mishima found intolerable, as the voice of the martyr spirits makes quite clear:

The reign of His Majesty has been dyed in two different colors. The period of the bloody red color ends with the last day of the war, and the period of the ash grey color begins from that day. The period of the authentic red color soaked with blood starts with the day when the utmost sincerity of the brotherly spirits was thrown away, and the period of that pallid grey color starts from the day of the ‘I-am-a-human’ announcement of His Majesty. The immortality of our deaths is thus desecrated.[5]

The “brotherly spirits” here refer to the soldiers of the failed 2.26 coup of 1936, failed by the Emperor Hirohito, by his headstrong refusal to understand and sympathize with their righteous patriotism and pure sincerity. Mishima also believed that the “I-am-a-Human” announcement of Hirohito in the wake of WWII rendered the heroic sacrifices of the lives of the Kamikaze Tokkottai (Special Attack Units) utterly futile and pointless.

According to the author, Mishima’s mother Shizue revealed a little secret about the writing of Voices of the Spirits of Martyrs on the occasion of the commemoration of the seventh anniversary of Mishima’s death, namely, the work was actually written one night. She recollected that Mishima handed the manuscript to her as he had always done and uttered “I wrote this in one stroke last night, and it’s now completed.” She read through it quickly, felt her “blood curdled,” and asked Mishima how he wrote this piece. Mishima answered: “I felt my hand moving naturally and the pen sliding on the paper freely. I simply couldn’t help it even if I wanted to stop my hand. Low voices as if murmuring could be heard across my room in the midnight. The voices seemed to be from a group of men. When I held my breath to listen carefully, I found they were the voices of the dead soldiers who had participated in the 2.26 Incident.” Shizue continued to remark that “I had known the saying about haunting spirits before but didn’t paid attention until that moment when I came to realize that Kimitake (Mishima’s real first name) was perhaps haunted by something, and I felt chills down my spine.”[6]

In the summer of the same year Voices of the Spirits of Martyrs was published, Mishima went to Kumamoto Prefecture on Kyushu Island, South Japan, and this trip would prove to have a decisively catalyzing effect on the consolidation of the nationalist and traditionalist ideology that guided his later literary and political actions, provided the urge for the writing of his final work The Sea of Fertility, and eventually paved the way for his suicide. The pivot of Mishima’s interest was the local Samurai warrior group Shinpuren (The League of Divine Wind) which was violently opposed to the various policies of westernizing reform enacted by the Meiji regime in the 1870s.

The original driving force of the Meiji Restoration was the idea of “Revering the Emperor and Repelling the Foreign Barbarians” (Sonnojoi), which stipulated that legitimacy came not from the Shogun but from the Emperor and that Western forces, epitomized by the dreaded “Black Ships,” must be decisively expelled.[7] Yet after abolishing the rule of the Tokugawa Shogunate by uniting around the rallying call of “Sonnojoi,” the newly-established Meiji regime immediately and drastically changed its course and started to purse a policy of reform: opening Japan to the outside world, imitating Western ways, and curbing or eliminating the traditional customs of Japanese society deemed by the new regime as un-Western and uncivilized. New laws were promulgated by the Meiji government: the former Shizoku (Samurai aristocrats) were prohibited from carrying swords in public places, a sacred and unalienable right in their eyes, marking their distinguished status from the masses. They were also forced to change their hairstyles (cutting off the buns at the back of their heads). These were the direct causes to the Insurrection of Shinpuren in 1876 (the ninth year of the Meiji period).

The members of Shinpuren were so thoroughly alienated and infuriated by the Meiji government that they went to comical lengths to reject modernity. For example, when banknotes replaced traditional metal coins, they refused to touch them with their hands, picking them up with chopsticks instead. They made long detours to avoid walking under electrical wires. If no detour was possible, they would cover their heads with a white paper fan and pass hurriedly under the wires. They cast salt on the ground after meeting anyone dressed in western garb. When they decided to revolt against the Meiji government, they insisted on using only traditional bladed weapons like the sword (Katana), spear (Yari), and cane knife (Naginata), instead of the “dirty weapons of the western barbarians.”

This group, consisting of about 170 men, launched a night-time attack on the Kumamoto garrison. The garrison troops were caught off guard and initially panicked. But they regrouped and started to fire volleys of bullets into the armor-wearing, sword-wielding Shinpuren warriors storming at them. The samurai fell one after another, and altogether 123 warriors died in the battle or committed seppuku after sustaining serious wounds, including a dozen 16- or 17-year-old teenagers.

It was indeed a sad and heart-wrenching story. Why were they willing to die to protect their right to carry samurai swords? It is hard to comprehend it by the commonsense of our de-spiritualized modern age. The rebellion was mocked by newspapers in Tokyo as an anachronism even at the time, let alone in post-War Japan. Nevertheless, the Shinpuren samurai believed they were serving the cause of righteousness and justice, and it was their spotless sincerity and combination of faith and action that deeply impressed Mishima. The following passage his comment on Shinpuren in a dialogue with Fusao Hayashi[8]:

Talk about the thoroughness of thinking, when thinking expresses itself in an action, there are bound to be impurities entering it, tactics entering it, and human betrayals entering it. This is the case with the concept of ideology in which ends always seem to justify means. Yet the Shinpuren was an exception to the mode of ends justifying means, for which ends equal means and means equal ends, both following the will of gods, thus being exempt from the contradiction and deviation of means and ends in all political movements. This is equivalent to the relation between content and style in arts. I believe there also lies the most essential, and in a sense the most fanatical sheer experimentation of the Japanese spirit (Yamatodamashii).[9]

As hinted previously, the trip to Kumamoto and the examination of the historical record of Shinpuren gave Mishima a model and meaning for his future suicide. In fact, three years before his suicide he published a piece in the Yomiuri Shinbun, in which he stated rather wistfully the following words: “I think forty-two is an age that is barely in time for being a hero. I went to Kumamoto recently to investigate the Shinpuren and was moved by many facts pertaining to it. Among those I discovered, one that struck me particularly was that one of the leaders of theirs named Harukata Kaya died a heroic death at the same age as I am now. It seems I am now at the ceiling age of being a hero.”[10] From such clues, which are actually numerous, the author argues that Mishima started at about forty to reflection on his own death and probably settled on terminating his own life upon the completion of his four-volume lifework The Sea of Fertility.

The heavy influence of Shinpuren is manifest in the second volume of The Sea of Fertility, namely Runaway Horses, in which the protagonist Isao Iinuma, a Right-wing youth, holds a pamphlet titled The Historical Story of Shinpuren and was depicted as possessing an burning aspiration of “raising a Shinpuren of the Showa age.” And the full content of the aforementioned book was inserted into Runaway Horses in the form of a minor drama within a major drama. The historical background of the novel was set in early 1930s. The 19-year-old Isao attempts to assassinate a man called Kurahara, known as the king fixer of backdoor financial dealing, who was in Mishima’s eyes the representation of Japanese bureaucrats who considered the “stability of currency” as the ultimate happiness of the people and preached a cool-headedly mechanical if not callous way of crafting economic policies. Kurahara was quoted saying, “Economics is not a philanthropy; you’ve got to treat 10% of the population as expendable, whereby the rest 90% will be saved, or the entire 100% will die” — the self-justifying words of a typical ultra-realist and even a nihilist — a stark contrast to the pre-War ideal of the Emperor as an absolute patriarch, a profoundly benevolent feudal ruler who guarded the identity, history, and destiny of the Japanese people — a metaphysical figure that Mishima embraced, held dear, and vowed to defend and revive regardless of cost.

In sum, Mishima’s spiritual and historical encounter with Shinpuren and his military training can be viewed as elements in the design of his own death, as steps ascending to the grand stage. Shortly after concluding his military training, Mishima wrote a short book, A Guide to Hagakure, on Jocho Yamamoto’ famous summation of Bushido doctrine, Hagakure. Mishima’s Guide also illuminates his final action:

One needs to learn the value of the martial arts to be pure and noble. If one wants to both live and die with a sense of beauty, one must first strive to fulfill necessary conditions. If one prepares longer, one will decide and act swifter. And though one can choose to perform a decisive action oneself, one cannot always choose the timing of such an action. The timing is made by external factors, is beyond a person’s powers, and falls upon him like a sudden assault. And to live is to prepare for such a fateful moment of being chosen by destiny, isn’t it?! Hagakure means to place stress on a prior awareness and a regulation of the actions for such preparations and for such moments that fate chooses you.[11]

It is exactly in such a fashion that Mishima prepared for and embraced his self-conceived and fate-ordained final moment, to serve a noble, beautiful, and righteous cause.

Notes

1. Emperor Hirohito was angry at the assassinations of his trusted imperial ministers at the hands of the rebel soldiers. He vehemently refused to lend an ear to the sincere patriotic views of the rebels, refused to side with them, and immediately ordered the suppression of the coup and had the leaders tried and executed quickly.

2. Emperor Hirohito made this announcement partly due to the pressure of the US occupation forces, i.e. the GHQ, and partly willingly, as a cooperative gesture if not an overtly eager attempt to ingratiate himself with the conqueror.

3. Naoki Inose, Persona: A Biography of Yukio Mishima (Tokyo: Bungei Shunshu Press, 1995), p. 323.

4. Meaning literally “a god appearing in human form,” a highly reverential reference to the Japanese Emperor until the end of WWII.

5. Persona, pp. 323, 324.

6. Persona, p. 324.

7. American naval fleets commanded by Commodore Matthew Perry to force Japan to open itself to the world, which first arrived in 1853 and once again in 1854.

8. A famous and highly accomplished literary figure of contemporary Japan who is known for being flamboyant and highly contentious writer and literary critic. As a young man, he was a Leftist, he turned toward the Right-wing nationalism in the 1930s and remained a staunch and steadfast nationalist during the war and throughout the post-war years until his death.

9. Persona, pp. 327, 328.

10. Persona, p. 333.

11. Persona, p. 341.

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2014/09/naoko-inoses-persona-a-biography-of-yukio-mishima/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/persona.jpg

[2] Persona: A Biography of Yukio Mishima: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1611720087/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=1611720087&linkCode=as2&tag=countecurrenp-20&linkId=62KCMLUZAWELMOLQ

00:08 Publié dans Littérature, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, littérature, littérature japonaise, lettres, lettres japonaises, yukio mishima, japon |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

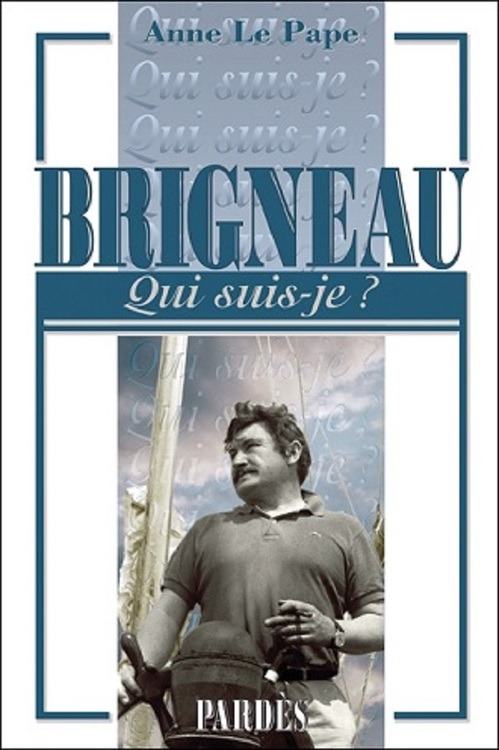

Brigneau: qui suis-je?

" Sous de multiples noms, François Brigneau a été journaliste, travaillant aussi bien pour la presse à grand tirage que pour des feuilles confidentielles voire clandestines. En 1965, rédacteur en chef d’un jeune mais vigoureux hebdomadaire, un sondage IFOP le désigna comme le deuxième journaliste le plus connu de France.

En 2012, à sa mort, le quotidien Le Monde, qui mettait un point d’honneur à ne pas le citer, se trouva toutefois obligé de lui consacrer une nécrologie. Il laisse une œuvre publiée abondante et variée : chroniques en langue parlée, romans policiers (il reçut en 1954 le Grand prix de littérature policière pour La beauté qui meurt), reportages à travers le monde, évocations de lieux, livres historiques, souvenirs de la vie journalistique et politique, etc.

Il a été apprécié par des hommes aussi différents que Frédéric Dard et Jean Madiran, Céline et Hubert Beuve-Méry, Robert Brasillach et Jean Gabin, Arletty et Marcel Pagnol, sans oublier Pierre Lazareff ou Alphonse Boudard. Pourquoi alors, pour reprendre un mot d’Alexandre Vialatte, fait-il aujourd’hui partie des auteurs «notoirement méconnus»? Tout simplement parce qu’au long de sa vie, fils d’un instituteur syndicaliste révolutionnaire mais s’étant toujours défini comme un Français de souche bretonne, François Brigneau, dont la plume valait une épée, a obstinément et fidèlement choisi « le mauvais camp», celui de «la France française», selon sa propre expression.

Ce « Qui suis-je?» Brigneau constitue la première biographie de ce journaliste de combat. Il s’appuie sur de nombreux entretiens avec lui et sur des archives familiales. “

00:07 Publié dans Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : françois brigneau, livre, france, polémique, polémistes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Comment éviter les naufrages de migrants en Méditerranée

Comment éviter les naufrages de migrants en Méditerranée, selon le New-York Times

Ce n'est pas le cas du NYT. Il n'hésite pas à reprocher à l'Europe son indifférence. Il conseille aussi à l'Europe un certain nombre de mesures permettant de sécuriser l'immigration clandestine. « The international community, especially Europe, must take collective action before more refugees die. Police and legal authorities must seek out and punish smugglers who kill or torture migrants. ».

Ceci d'autant plus que, selon l'article, le nombre des immigrants est passé de 60.000 en 2013 à 130,000 en 2014, chiffres fournis par l'International Organization for Migration . Le mouvement ne fera que s'amplifier. Des centaines de milliers de Syriens, Palestiniens, Soudanais et Érythréens sont en instance de passage, notamment vers l'Italie.

Après avoir constaté que les mesures actuelles, Mare Nostrum en Italie, Frontex au niveau de l'Union européenne, seront insuffisantes pour empêcher l'afflux de ces populations, le NYT déclare que « The only way to stop desperate people from risking their lives with unscrupulous traffickers is to give more of them a legal path to safety in Europe ». « La seule façon de protéger les immigrants de trafiquants sans scrupules est d'organiser des voies d'accès sécurisées à l'Europe ».

Il est curieux d'entendre ce conseil de la part du journal de référence d'un pays qui militarise progressivement ses frontières avec le Mexique, et qui n'hésite pas à mobiliser la Garde Nationale et l'armée pour faire tirer sur les clandestins. La télévision française avait réalisé récemment un reportage sur une milliardaire américaine qui avait acheté un gros yacht destiné à récupérer des migrants en difficulté en Méditerranée, afin de les aider à entrer en Europe. A la question de savoir si elle irait jusqu'à les héberger chez elle en Amérique, elle n'avait pas répondu.

Ce n'est certainement pas en offrant de plus larges facilitées d'entrée sur le territoire européen que l'on diminuera le nombre des passeurs et celui de leurs exactions. Au contraire. Ceux-ci s'industrialiseront de plus en plus si l'on peut dire, en aggravant le prix à payer pour leurs services. La question de l'immigration dite de la misère, qui s'aggravera prochainement avec l'afflux de réfugiés climatiques, imposerait des actions intergouvernementales de grande ampleur. L'Amérique, en ce qui la concerne, pourrait s'attaquer sérieusement à la diminution de ses émissions de gaz à effet de serre, comme l'a fait l'Europe. En attendant, nous n'avons aucun besoin des bons conseils du NYT.

00:06 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : new york times, politique internationale, méditerranée, europe, affaires européenne, frontex, agence frontex, immigration, immigration sauvage |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Exoficial de EE.UU.: "EI Estado Islámico es un monstruo creado por nosotros"

El EI es "una creación, un monstruo, un Frankenstein creado por nosotros". Un exoficial de la Marina de EE.UU., Kenneth O’Keefe, revela en una entrevista estos y otros hechos chocantes sobre el rol de EE.UU. en el surgimiento del grupo terrorista.

El exoficial no pone en ninguna duda el hecho de que los extremistas del EI, que opera en Irak y Siria, han sido financiados por EE.UU. a través de sus representantes como Catar, Emiratos Árabes Unidos y Arabia Saudita. "Realmente, todos son solo una forma rebautizada de Al Qaeda, que por supuesto no es nada más que una creación de la CIA", dice O'Keefe.

O'Keefe relata en una entrevista a Press TV que los yihadistas no solo han recibido de EE.UU. "el mejor equipo norteamericano" como el blindaje personal, blindados de transporte de tropas y entrenamiento, sino que también han sido "permitidos a inundar a través de las fronteras" en muchos lugares del Oriente Medio. "Todo esto se ha hecho bajo el auspicio de acabar con el último 'Hitler' a ojos de Occidente, Bashar al Assad", afirma.

El experto también está de acuerdo con la opinión de algunos analistas de que EE.UU. utiliza toda esta situación con el EI como "una puerta trasera", persiguiendo su objetivo básico de eliminar el Gobierno de Al Assad. El mismo patrón se ve en Irak y Afganistán, añade el exoficial.

Y el pueblo estadounidense, según O'Keefe, no puede ver la situación verdadera por los efectos de la propaganda. "Sería absurdo pensar que el pueblo estadounidense está tan sintonizado en el entendimiento de lo que realmente está pasando como para no ser engatusado en otra guerra que no hará nada más que destruir a cualquiera que participe en ella", concluye.

La conexión saudí: ¿Por qué EE.UU. no vio venir la amenaza del Estado Islámico?

EE.UU. pasó por alto el surgimiento del EI, al hacer antaño la vista gorda ante el papel de Arabia Saudita como promotor de movimientos yihadistas como Al Qaeda, entre los que el EI es el más exitoso, opinan expertos.

El presidente estadounidense, Barack Obama, está repitiendo los errores del pasado en su lucha contra el Estado islámico (EI), opina el senador Bob Graham, copresidente de la Comisión sobre la propagación de Armas de Destrucción Masiva y Terrorismo, y expresidente de la Comisión de Inteligencia del Senado.

De hecho, según él, EE.UU. sigue sin hacer caso al papel de Arabia Saudita, que durante años apoyó al extremismo sunita, tanto a Al Qaeda como al Estado Islámico. Aunque ahora, cuando el EI controla ya territorios más extensos que Reino Unido en Siria e Irak, Arabia Saudita ya no apoya este movimiento, antes "fue una figura central para financiar al EI y otros grupos extremistas", insiste el senador, citado por el diario 'The Independent' .

Según la investigación del ataque del 11 de septiembre, muchas donaciones privadas a Al Qaeda provinieron precisamente de Arabia Saudita. Según él, EE.UU. nunca se dedicó a estudiar ni estos vínculos con los radicales sunitas, ni la posible involucración de Arabia Saudita en el acto terrorista del 11 de septiembre, a pesar de que 15 de los 19 secuestradores de aviones eran de nacionalidad saudí. En vez de ello, EE.UU. ha seguido tratando a este país como su aliado y "siguió haciendo la vista gorda ante el apoyo de Arabia Saudita a los extremistas sunitas", escribe 'The Independent'.

Esto "contribuyó a la capacidad de Arabia Saudita de continuar involucrándose en las acciones perjudiciales para EE.UU., en particular su apoyo al EI", afirmó. Pero, además, el hecho que EE.UU. trataba a Arabia Saudita como un "aliado fiable" e "ignorara" su apoyo a extremistas es la razón por qué la inteligencia estadounidense falló a la hora de identificar al EI como una "amenaza creciente", según cita al senador 'The Independent'.

La semana pasada Obama anunció la nueva estrategia de la lucha contra el EI, al que prometió atacar "allá donde esté". Uno de puntos clave de la estrategia pasa por entrenar a milicianos "moderados" tanto contra el presidente sirio Bashar al Assad, como contra el EI en territorio saudí. Teniendo en cuenta la costumbre de Arabia Saudita de no limitarse a apoyar a los sunitas, y colaborar con los más radicales, este paso podría resultar peligroso, advierte Graham.

EIIL utiliza armas propiedad del Gobierno de Estados Unidos

El grupo terrorista EIIL (Daesh, en árabe) utiliza armas provenientes de Estados Unidos, así ha revelado la organización Conflict Armament Research en un estudio publicado este lunes.

El informe que documentó las armas incautadas en el norte de Irak por las fuerzas kurdas ‘peshmarga’ en el pasado mes de julio, indica que los terroristas del EIIL poseen “cantidades significativas” de armamento fabricado en EE.UU., incluyendo rifles de asalto M16.

Los rifles, añade el reporte, llevan marcas que dicen: Propiedad del Gobierno de Estados Unidos.

El informe, también, encontró que los cohetes antitanques utilizados por Daesh en Siria eran idénticos a los M79 transferidos por Arabia Saudí al denominado Ejército Libre de Siria (ELS).

El pasado mes de septiembre, la página Wikileaks reveló que el Gobierno de Washington, en lugar de ayudar al Ejecutivo sirio en su lucha contra el terrorismo, financia los grupos terroristas.

Asimismo, el diario estadounidense ‘The Washington Post’, en un artículo publicado el año pasado, dejó claro que la Agencia Central de Inteligencia de EE.UU. (CIA, por sus siglas en inglés) suministró armamento a los grupos armados en Siria.

Después de que el EIIL se apoderara de varias zonas en Siria e Irak, varias personalidades y documentos filtrados revelaron el rol de Washington y sus aliados en la creación de ese grupo takfirí o el apoyo que le brindan para provocar el caos en la región.

El exanalista de la Agencia de Seguridad Nacional de EE.UU. (NSA, por sus siglas en inglés), Edward Snowden, reveló recientemente que el EIIL fue creado mediante un trabajo conjunto entre los servicios de Inteligencia de Estados Unidos, el Reino Unido y el régimen de Israel.

Asimismo, la exsecretaria de Estado de EE.UU., Hillary Clinton, confesó en su libro de memorias que Washington formó al grupo Daesh para alcanzar sus objetivos en Oriente Medio.

El EIIL cuenta con miles de millones de dólares y casi 15 mil mercenarios, y lucha en dos frentes, en Siria e Irak, con la intención de crear un Estado propio entre estos dos países árabes.

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : eiil, terrorisme, djihad, djihadisme, états-unis, politique internationale, géopolitique, irak, syrie, moyen orient, proche orient, levant, fondamentalisme islamique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Site de Stonehenge

La légende veut que Merlin ait amené les pierres de Stonehenge d'Irlande, en une nuit. Aujourd'hui, même si on a relégué l'enchanteur dans les livres de contes, on ne sait toujours pas exactement comment les constructeurs du monument mégalithique ont pu amener plus de 80 "pierres bleues" de 3 ou 4 tonnes chacune depuis le pays de Galles, un trajet de plus de 300 kilomètres en terrain accidenté, et ce voici plus de 41 siècles. Ou comment, une centaine d'années plus tard, ils ont transporté sur une trentaine de kilomètres d'autres blocs, en grès massif, de 50 tonnes Et ce n'est que l'un des nombreux mystères de ce site sacré, étonnant monument : lieu de culte, de sépultures, observatoire solaire...

La légende veut que Merlin ait amené les pierres de Stonehenge d'Irlande, en une nuit. Aujourd'hui, même si on a relégué l'enchanteur dans les livres de contes, on ne sait toujours pas exactement comment les constructeurs du monument mégalithique ont pu amener plus de 80 "pierres bleues" de 3 ou 4 tonnes chacune depuis le pays de Galles, un trajet de plus de 300 kilomètres en terrain accidenté, et ce voici plus de 41 siècles. Ou comment, une centaine d'années plus tard, ils ont transporté sur une trentaine de kilomètres d'autres blocs, en grès massif, de 50 tonnes Et ce n'est que l'un des nombreux mystères de ce site sacré, étonnant monument : lieu de culte, de sépultures, observatoire solaire...

Ce travail a révélé rien moins que 17 nouveaux monuments de l'époque à laquelle Stonehenge a été achevé. Des douzaines de sépultures ont également été placées sur la carte, ainsi que de très grandes fosses, parfois de 4 mètres de profondeur, dont certaines correspondraient à des alignements astronomiques.

Ce travail a révélé rien moins que 17 nouveaux monuments de l'époque à laquelle Stonehenge a été achevé. Des douzaines de sépultures ont également été placées sur la carte, ainsi que de très grandes fosses, parfois de 4 mètres de profondeur, dont certaines correspondraient à des alignements astronomiques.

Le grand fossé connu sous le nom de Cursus, et qui constituait une barrière symbolique avant l'accès à Stonehenge, a lui aussi révélé de nouveaux secrets. Datant de 3.500 ans avant notre ère, il s'étale sur 3 kilomètres, et fait environ 100 mètres de large, avec une fosse sur son côté est. Ce que l'on ne savait pas, c'est ce qui était à l'intérieur. Cette nouvelle recherche a permis de trouver une seconde fosse à l'autre bout du Cursus, dans le prolongement de la fameuse "Heel Stone" qui marque l'entrée de Stonehenge et qui était alignée avec le coucher du soleil lors du solstice d'été. Les archéologues ont également découvert des brèches dans le Cursus, permettant l'accès à Stonehenge. De quoi imaginer cette grande allée, d'est en ouest, comme une sorte de voie de procession rituelle suivant la course du soleil, avec des lignes allant du sud au nord qui guidaient les visiteurs dans leur accès au cercle de pierres, comme le décrit le professeur Vincent Gaffney, archéologue à l'université de Birmingham et leader du projet, au site du Smithsonian Institute.

Le grand fossé connu sous le nom de Cursus, et qui constituait une barrière symbolique avant l'accès à Stonehenge, a lui aussi révélé de nouveaux secrets. Datant de 3.500 ans avant notre ère, il s'étale sur 3 kilomètres, et fait environ 100 mètres de large, avec une fosse sur son côté est. Ce que l'on ne savait pas, c'est ce qui était à l'intérieur. Cette nouvelle recherche a permis de trouver une seconde fosse à l'autre bout du Cursus, dans le prolongement de la fameuse "Heel Stone" qui marque l'entrée de Stonehenge et qui était alignée avec le coucher du soleil lors du solstice d'été. Les archéologues ont également découvert des brèches dans le Cursus, permettant l'accès à Stonehenge. De quoi imaginer cette grande allée, d'est en ouest, comme une sorte de voie de procession rituelle suivant la course du soleil, avec des lignes allant du sud au nord qui guidaient les visiteurs dans leur accès au cercle de pierres, comme le décrit le professeur Vincent Gaffney, archéologue à l'université de Birmingham et leader du projet, au site du Smithsonian Institute.

00:05 Publié dans archéologie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : archéologie, stonehenge, grande-bretagne, préhistoire, mégalithes, sites mégalithiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook