mercredi, 13 juillet 2011

Heidi Brühl (1966): Hundert Mann und ein Befehl

Heidi Brühl - 1966

Hundert Mann und ein Befehl

00:05 Publié dans Militaria, Musique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : allemagne, musique, militaria |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 26 mai 2011

Adzharian Dance - Horumi / Igor Moiseev's Ballet

Adzharian Dance - Horumi

Igor Moiseev's Ballet

00:04 Publié dans Musique, Terres d'Europe, Terroirs et racines | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : adjarie, géorgie, caucase, russie, musique, ballet, danse, terres d'europe |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 02 mai 2011

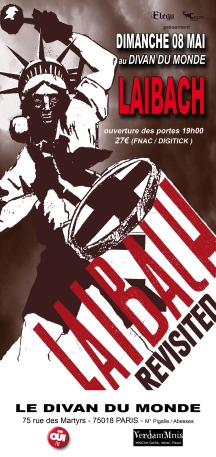

Laibach à Paris

17:12 Publié dans Evénement, Musique, Musique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : musique, laibach, slovénie, paris, événement |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 27 avril 2011

Franz Lehar - Adria Waltz

Franz Lehar - Adria Waltz

00:05 Publié dans Musique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : musique, franz lehar, adriatique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 07 avril 2011

Carmina Burana - Dulce Solum - Carl Orff

Carmina Burana - Dulce Solum - Carl Orff

00:05 Publié dans Musique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : musique, carmina burana, carl orff, moyen âge, allemagne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 01 avril 2011

"Preussens Gloria" auf dem Roten Platz in Moskau

"Preussens Gloria" auf dem Roten Platz in Moskau

00:05 Publié dans Militaria, Musique, Musique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : musique, militaira, allemagne, russie, moscou, bundeswehr, armées, musique militaire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 31 mars 2011

Marcha de los Jinetes de Fehrbelliner - Ejercito de Chile

Marcha de los Jinetes de Fehrbelliner

Ejercito de Chile

00:05 Publié dans Militaria, Musique, Musique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : chili, armées, musique militaire, militaria |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 30 mars 2011

Anne-Marie du 3°REI - Légion Etrangère

Anne-Marie du 3°REI

Légion Etrangère

00:05 Publié dans Militaria, Musique, Musique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : légion etrangère, france, musique, armées, militaria |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 06 mars 2011

Camerata Mediolanense - Il Lupo (1994) & Fuoco

Camerata Mediolanense - Il Lupo (1004)

Fuoco

00:05 Publié dans Musique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : camerata mediolanense, italie, musique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 04 février 2011

André Rieu / Mirusia Louwerse: Solveig's Song

André Rieu / Mirusia Louwerse : Solveig's Song

00:05 Publié dans Musique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : grieg, musique, andré rieu, norvège |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 24 novembre 2010

30 Jahre Laibaich: Total totalitäre Retro-Avantgardisten

30 Jahre Laibach: Total totalitäre Retro-Avantgardisten

Das Kunstmagazin MONOPOL setzt in der aktuellen November-Ausgabe einen Schwerpunkt auf Kollektive und beschäftigt sich in der Titelgeschichte mit der slowenischen Industrial-Band Laibach. Diese versteht sich selbst als „Gesamtkunstwerk“. Um dies zu dokumentieren, haben die umstrittenen Musiker dieses Jahr zum 30. Geburtstag ihrer Band eine Ausstellung, ein Symposium und mehrere Konzerte durchgeführt.

Daniel Völzke und Martin Fengel von MONOPOL durften Ende September zu den Feierlichkeiten nach Slowenien reisen. Der Aufwand hat sich jedoch nicht gelohnt. Hauptsächlich trägt ihre Reportage die Meinungen und Erkenntnisse zu der provokanten Band zusammen, die sich in den letzten Jahrzehnten so angehäuft haben. Auf der einen Seite steht dabei der Vorwurf, Laibach würden sich faschistischer Ästhetik bedienen. Auf der anderen dann die Erklärung: Das ist nur „Über-Identifikation“ mit totalitären Systemen, mit der diese letztendlich ad absurdum geführt werden.

Der Kunstwissenschaftler Boris Groys spricht von einer Inszenierung, die „totaler als der Totalitarismus“ sei. Laibach selbst sagen dazu wenig. Entweder geben sie Statements ab, auf die die Presse nur so wartet. Zum Beispiel:

Wir sind genauso Faschisten, wie Hitler ein Maler war.

Oder sie erklären allgemeine Sachverhalte ohne jegliche Spezifik. Daniel Völzke haben sie vorgeträllert:

Wir glauben an eine Kunst, die soziale, politische und wirtschaftliche Reformen voranbringt, aber auch an Kunst, die die Grenzen ästhetischer Erfahrung austestet. In kollektiv organisierten Bewegungen entwickeln sich diese beiden Vorhaben organischer.

Damit sind wir genauso klug wie vorher.

Das Prinzip der Retro-Avantgarde, das die Slowenen anwenden, besteht darin, mit unzähligen historischen Versatzstücken (NS-Propaganda, Sozialistischer Realismus, christliche Ikonographie) die empfindlichsten Stellen unserer Identität anzusteuern. Das Ziel ist dabei kein politisches. Es geht vielmehr um die maximale energetische Mobilisierung des Betrachters. Dies kann sich in Empörung, frenetischem Jubel oder gar körperlicher Ekstase ausdrücken.

Laibach sind sich dabei bewußt darüber, was ihr derzeit größtes Problem ist. Auf dem Symposium betonte Gründungsmitglied Ivan Novak:

Es ist leicht, neu zu sein, wenn man neu ist, aber es ist schwer, wenn man alt ist wie wir.

Im Klartext: Provokation nutzt sich mit der Zeit ab. Wahrscheinlich hat die Industrial-Band daher ihren Höhepunkt schon hinter sich und weiß das sogar. Im Dezember gibt sie mehrere Konzerte in Deutschland. Bei Youtube kann man außerdem einen faschistischen Tanzkurs mit Laibach belegen. Danach wird jeder – fernab jeglicher Politik – wissen, wie faschistische Ästhetik auf ihn wirkt.

00:10 Publié dans Musique, Musique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : musique, laibach, slovénie, avant-garde, avant-garde musicale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

30 Jahre Laibach (2)

30 Jahre Laibach (II)

Martin LICHTMESZ - Ex: http://www.sezession.de/

Noch ein paar Anmerkungen zum 30-Jahres-Jubiläum von Laibach, als deren Fan ich mich neulich in diesem Blog bekannt habe. Seit ihrer Gründung im Jahr 1980 hat sich nicht nur die Welt, sondern auch die Gruppe stark verändert (musikalisch eher zu ihren Ungunsten), von deren Originalbesetzung zur Zeit eigentlich nur noch Frontmann Milan Fras und Ivan Novak übriggeblieben sind.

In einem gewissen Sinne ist die slowenische Formation seit zwei Jahrzehnten nur mehr ein Recycler ihres eigenen Mythos, dessen Wirkungsmacht eben eng verknüpft war mit dem Entstehungskontext des Projekts im post-titoistischen Jugoslawien (1980 war auch das Todesjahr des kultisch verehrten Staatspräsidenten, damit auch das Jahr, in dem der durch Blut und Eisen zusammengeschusterte Vielvölkerstaat langsam auseinanderzubröckeln begann).

Schon die Wahl des deutschen Namens für Ljubljana war eine gezielte Provokation der damaligen jugoslawischen Autoritäten. Diese waren nun in den Achtziger Jahren bereits lax und vom liberalen Rückenmarkschwund befallen genug (in der DDR wurde zur gleichen Zeit jede harmlose Amateur-Punk-Combo von der Stasi plattgemacht), daß die Band sich mühelos als „totalitärer“ als das herrschende Regime inszenieren konnte, „päpstlicher als der Papst“ sozusagen. In der Art und Weise, wie es Laibach taten, wollte der Staat zu diesem Zeitpunkt eigentlich gar nicht mehr beschworen und glorifiziert werden.

In Slowenien und Kroatien hatte man es zu einem relativen Wohlstand gebracht, und wenig ahnte man von dem verheerenden Krieg, der nur ein Jahrzehnt später ausbrechen sollte. Um 1983 herum waren Laibachs martialische Beschwörungen und Über-Emphasen der alten kommunistischen Kampf-, Askese-, Aufopferungs- und Hauruck-Rhetorik, untermalt mit aufpeitschender Krachmusik, peinlich, unheimlich, irritierend, angriffig. Der ästhetische Mix aus kommunistisch-stalinistischen mit faschistischen und nationalsozialistischen Elementen, der sich in der Mitte der Dekade noch verstärken sollte, wirkte natürlich zusätzlich subversiv, und dekonstruierte durch Annäherung und Amalgamierung den „antifaschistischen“ Mythos der kommunistischen Ideologie. Laibach attackierten indirekt den sozialistischen Staat, indem sie ihn scheinbar von rechts überholten, und ihn in Beziehung setzten zum feindlichen Bruder Nationalsozialismus.

In einem berüchtigten frühen TV-Auftritt setzte sich die Gruppe mit sinistrer Beleuchtung, blanken Stiefeln, undefinierbaren Uniformen und Armbinden mit schwarzen Kreuzen in Szene, schwieg mit eisernen Mienen, während der Frontmann die tribunalartigen Fragen des Interviewers beharrlich ignorierte, und stattdessen lange, komplizierte Manifeste vorlas: „Laibach behandelt die Beziehung zwischen Kunst und Ideologie, die Spannungen, die durch Expression subliminiert werden. Darum wird jeder direkte ideologische Diskurs eliminiert. Unsere Aktivität steht über direktem Engagement… wir sind komplett unpolitisch.“ Und so weiter und so fort. Zur selben Zeit konnte man im Jugo-TV Pop-Videos (siehe hier, hier und hier) sehen, die sich in nichts von dem unterschieden, was gerade im Westen „in“ war.

Mit dem Album Opus Dei von 1987 begannen Laibach ihre berüchtigte Serie „faschisierter“ oder auf „martialisch“ getrimmter Cover-Versionen von populären Songs, für die sie am besten bekannt sind (darunter Titel von den Beatles, den Rolling Stones, Prince, Status Quo und, als Meta-Pop-Witz, DAF). Fanfaren und Trompeten, epischer Sound, militärisch stampfendes Schlagzeug, ins Deutsche übertragene Texte und der forciert markige Gesang an der Grenze zur Selbstparodie (den später Rammstein kopierten) verfremdeten bekannte Melodien auf eine verblüffende Weise.

Der Klassiker schlechthin ist ihre Version des Superhits „Life is live“ („Nananana“) der österreichischen Gruppe Opus, der damals in den Diskotheken weltweit ad nauseam rauf und runter lief. Zusammen mit dem Video, in dem Laibach durch die Berge stapfen und vor monumentalen Wasserfällen posieren, voller zur Schau getragenem Sendungsbewußtsein und mit kultischem Gestus, hatte das einen ganz besonderen Touch, der die Gruppe von nun an definieren sollte.

Der Reiz ergibt sich aus dem Ineinander von verschiedenen widersprüchlichen Komponenten: einerseits handelt es sich hierbei natürlich offensichtlich um einen schreiend komischen Witz und um bewußt auf die Spitze getriebenen Camp. Andererseits hat es auch eine hin- und mitreißende Wirkung: der charismatische, kraftstrotzende Sänger mit dem Schnauzbart, der seltsamen Wüstenlegionärs-Kopfbedeckung und dem schmucken Alpen-Trachten-Outfit vor der Kulisse schneebedeckter Gipfel und rückwärts (!) strömender Wasserfluten – das geht weit über den bloßen „dekonstruktiven“ Gag hinaus. Die heroisch-teutonische Ästhetik wird ebenso zelebriert wie ironisiert. Es ist komisch und parodistisch, aber eben auch – geil.

Laibach demonstrierten, wie mit wenigen Handgriffen ein banaler Popsong einen „faschistischen“ Sound und Subtext erhalten kann. In der Alternativ-Version „Leben heißt Leben“ haben sie den englischen Originaltext eingedeutscht und nur geringfügig verändert:

When we all give the power

We all give the best

Every minute of an hour

Don’t think about the rest

Then you all get the power

You all get the best

When everyone gives everything…Wann immer wir Kraft geben,

geben wir das Beste,

All unser Können, unser Streben

und denken nicht an Feste,

Von jedem wird alles gegeben,

und jeder kann auf jeden zählen,

Leben heißt Leben!Life is life, when we all feel the power

Life is life, come on, stand up and dance

Life is life, when the feeling of the people

Life is life, is the feeling of the band!Leben heißt Leben -

Wenn wir alle die Kraft spüren!

Leben heißt Leben -

Wenn wir alle den Schmerz fühlen!

Leben heißt Leben!

Heißt die Mengen erleben

Leben heißt Leben -

Heißt das Land erleben…

Auf analoge Weise verwandelten Laibach „One Vision“ von Queen zu „Geburt einer Nation“, der einen ähnlichen „Klassiker“-Status wie „Life is live“ hat. Da mußte der Text lediglich wörtlich übersetzt werden.

One man, one goal

One mission,

One heart, one soul

Just one solution,

One flash of light

One God, one vision

One flesh, one bone,

One true religion,

One voice, one hope,

One flesh one bone

One true religion

One race, one hope

One real decision

Wowowowo oh yeah oh yeah oh yeahEin Mensch – ein Ziel

und eine Weisung.

Ein Herz – ein Geist,

nur eine Lösung.

Ein Brennen der Glut.

Ein Gott – ein Leitbild.Ein Fleisch – ein Blut,

ein wahrer Glaube.

Eine Rasse, ein Traum,

und ein starker Wille

Gebt mir ein Leitbild! Ja, Ja, Jawoll, Jaaa!!

Und nun sehe man sich an, wie Queen 1985 in Rio de Janeiro ein Stadion mit zigtausend Menschen zum Mitstampfen von „We will rock you“ bringen, während Frontmann Freddie Mercury mit nacktem, muskulösem Oberkörper, in einen Union Jack gehüllt, vor den Massen auf und ab gockelt und sie dabei beherrscht wie ein schriller Glamrock-Mussolini:

Laibach haben also natürlich auch die unterirdischen Beziehungen zwischen Pop als Massenphänomen und totalitären Massenbewegungen angesprochen, die schon David Bowie in den Siebzigern in das berüchtigte Bonmot „Hitler war der erste Popstar“ faßte. Man kann auch an Jean Genet denken, der einmal bemerkte, der Faschismus sei „essentielment“ Theater.

Im Pop ist es auch kein notwendiger Widerspruch, eine Pose ausgiebig zu genießen und abzufeiern, und gleichzeitig ihre Künstlichkeit und ihren augenzwinkernden Showcharakter zu betonen. Man denke etwa an die prunkvollen Phantasie-Uniformen und den Erlösergestus von Michael Jackson. Rockstars befriedigen in demokratischen Zeiten tief sitzende monarchische Bedürfnisse, sind in ihren Welten Könige, Absolutisten, Messiase, Diktatoren, Fabeltiere, die die Huldigungen der Fanmassen entgegennehmen, über die sie Kraft ihrer Kunst herrschen, und die sich ihrerseits willig dem regressiv-wonnigen Rausch der Fan-Volks-Gemeinschaft hingeben.

In Umkehrung zu Genet läßt sich fragen, inwiefern die Kanalisierung „totalitärer“ Versatzsstücke und Ansprüche in eine Bühnenshow und ein Kunstprodukt wie den NSK-“Staat“, das, was Armin Mohler die „monumentale Unternährung“ nannte, gleichsam entpolitisieren, entschärfen und auf einer rein ästhetischen Ebene befriedigen kann. Denn wären Laibach auf reine Parodie und Dekonstruktion aus gewesen, wäre ihr Appeal nicht so stark und dauerhaft gewesen.

Mir schien es jedenfalls eher immer so, daß Laibach, sobald sie von den westlichen Intellektuellen nach einer gewissen Irritationsphase als „Kunst“ akzeptiert wurden, auch ein Ventil für jene boten, die endlich einmal guten Gewissens ihren lang verdrängten „inneren Faschisten“ ausleben wollten. Wenn die Gruppe Mitte der Neunziger in Wien auftrat, dann waren die Konzerte voll mit Lesern von alternativhippen linksliberalen Blättern wie Standard und Falter, die nun die unterdrückte Fascho-Sau rauslassen konnten und mit ausgestrecktem rechten Arm der Bühne entgegensalutierten: „Und dann feiern wir Vereinigung, die ganze Nacht! Jawollll, Jaaaa!!“ Und in der damaligen Gothic-und Wave-Nacht im Wiener U4 konnte man schon mal erleben, daß sich zu „Life is Live“ spontan ganze Marschformationen auf der Tanzfläche bildeten, die im Gleichschritt zu tanzen begannen.

Ich habe mich oft gefragt, wie sehr die hysterische Kontaminationsangst mancher Zeitgenossen vor riefenstahl’scher oder speer’scher Ästhetik auf einer uneingestandenen Faszination beruht, die man in streng puritanischer Weise nicht einmal vor sich selber zuzugeben wagt. Mit Sicherheit spüren aber sehr viele Menschen immer noch die spezifische Anziehungs- und Suggestionskraft dieser Bilder, die offenbar tiefsitzende, unausrottbare Gefühle ansprechen. Oder wie ein Soziologe in den Siebziger Jahren, dessen Namen mir entfallen ist, einmal sinngemäß und in anprangernder Absicht sagte: Faschismus befriedigt menschliche Grundbedürfnisse. (Wenn das stimmt, was folgern wir daraus? Und was ist dann noch „Faschismus“?)

Mit dem Zerfall des Ostblocks verloren Laibach den Reibungskontext, in dem sie sich ursprünglich bewegten. Ihr Ansatz geriet zunehmend zur Masche, und man merkte, daß sie nun mit Alben wie „Kapital“ (1992) und „Nato“ (1994) auf der Suche nach neuen zu unterwandernden Angriffsflächen waren. (Der Liberalismus jedoch ist im Gegensatz zum National- und Internationalsozialismus leider ein allzu elastischer Gegner, der jede Opposition wie ein Schwamm aufzusaugen vermag.) Das wirkte dann ein wenig wie eine etwas verräterische, weil dem undurchsichtigen Image der Band abträgliche Ideologie-Revue, die aber mit der Methode Laibach nicht so recht zu knacken war.

Am wenigsten überzeugend geriet dabei das Album „Jesus Christ Superstars“ (1996), das sich nun dem „ideologischen“ Rahmen der Religion widmete und Milan Fras im Gewand eines Pilgers oder Predigers präsentierte. Das war nun doch etwas zu einfach. „Tanz mit Laibach“, eine Art Remake des DAF-Hits „Tanz den Mussolini“ ging nochmal „back to the roots“, aber wie die Nazistiefel-Dauerschleife in dem Video war das kaum mehr als ein altgewordener, auf der Stelle tretender Witz.

Gelungener (und bei weitem die interessanteste Veröffentlichung der letzten eineinhalb Jahrzehnte) war da schon das 2006er Album „Volk“, das ausschließlich Interpretationen von Nationalhymen enthielt. Das geschah mit quasi-“ethnopluralistischer“ Verve und einem Minimum an Ironie, trotz der Herdenschäfchen auf dem Cover. Hier ist die „dekonstruktive“ Absicht deutlich zurückgetreten, und hier zeigt sich auch, daß Laibach sich doch nicht so einfach in einen „linken“ Kulturbetrieb eingemeinden und abhaken lassen, wie manche voreilig beschwichtigend meinen.

Darin schließe ich mich dem Urteil von Dominik Tischleder in der JF an:

Ganz ohne interpretatorisch doppelten Boden wird hier ein „Denken in Völkern“ als popmusikalisches Panorama entfaltet. Nationale Identität scheint als politischer Faktor ersten Ranges identifiziert.Nicht zuletzt deshalb ist „Volk“ ein intellektuell stimulierendes Album geworden, bei dem die eigentliche Musik fast schon Nebensache ist. Laibach selbst drücken es so aus: „Pop ist Musik für Schafe, und wir sind die als Schäferhunde verkleideten Wölfe.“

00:10 Publié dans Musique, Musique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : musique, laibach, slovénie, avant-garde, musique avant-gardiste |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 17 juillet 2009

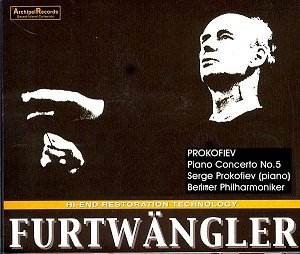

W. Furtwängler and Music in the Third Reich

Wilhelm Furtwängler and Music

in the Third Reich

Antony Charles - http://www.gnosticliberationfront.com/Not only during his lifetime, but also in the decades since his death in 1954, Wilhelm Furtwängler has been globally recognized as one of the greatest musicians of this century, above all as the brilliant primary conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic orchestra, which he lead from 1922 to 1945, and again after 1950. On his death, the Encyclopaedia Britannica commented: "By temperament a Wagnerian, his restrained dynamism, superb control of his orchestra and mastery of sweeping rhythms also made him an outstanding exponent of Beethoven." Furtwängler was also a composer of merit

Underscoring his enduring greatness have been several recent in-depth biographies and a successful 1996 Broadway play, "Taking Sides," that portrays his postwar "denazification" purgatory, as well as steadily strong sales of CD recordings of his performances (some of them available only in recent years). Furtwängler societies are active in the United States, France, Britain, Germany and other countries. His overall reputation, however, especially in America, is still a controversial one.

Following the National Socialist seizure of power in 1933, some prominent musicians -- most notably such Jewish artists as Bruno Walter, Otto Klemperer and Arnold Schoenberg -- left Germany. Most of the nation's musicians, however, including the great majority of its most gifted musical talents, remained -- and even flourished. With the possible exception of the composer Richard Strauss, Furtwängler was the most prominent musician to stay and "collaborate."

Consequently, discussion of his life -- even today -- still provokes heated debate about the role of art and artists under Hitler and, on a more fundamental level, about the relationship of art and politics.

A Non-Political Patriot

Wilhelm Furtwängler drew great inspiration from his homeland's rich cultural heritage, and his world revolved around music, especially German music. Although essentially non-political, he was an ardent patriot, and leaving his fatherland was simply out of the question.

Ideologically he may perhaps be best characterized as a man of the "old" Germany -- a Wilhelmine conservative and an authoritarian elitist. Along with the great majority of his countrymen, he welcomed the demise of the ineffectual democratic regime of Germany's "Weimar republic" (1918-1933). Indeed, he was the conductor chosen to direct the gala performance of Wagner's "Die Meistersinger" for the "Day of Potsdam," a solemn state ceremony on March 21, 1933, at which President von Hindenburg, the youthful new Chancellor Adolf Hitler and the newly-elected Reichstag formally ushered in the new government of "national awakening." All the same, Furtwängler never joined the National Socialist Party (unlike his chief musical rival, fellow conductor Herbert von Karajan).

It wasn't long before Furtwängler came into conflict with the new authorities. In a public dispute in late 1934 with Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels over artistic direction and independence, he resigned his positions as director of the Berlin Philharmonic and as head of the Berlin State Opera. Soon, however, a compromise agreement was reached whereby he resumed his posts, along with a measure of artistic independence. He was also able to exploit both his prestigious position and the artistic and jurisdictional rivalries between Goebbels and Göring to play a greater and more independent role in the cultural life of Third Reich Germany.

From then on, until the Reich's defeat in the spring of 1945, he continued to conduct to much acclaim both at home and abroad (including, for example, a highly successful concert tour of Britain in 1935). He was also a guest conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic, 1939-1940, and at the Bayreuth Festival. On several occasions he led concerts in support of the German war effort. He also nominally served as a member of the Prussian State Council and as vice-president of the "Reich Music Chamber," the state-sponsored professional musicians' association.

Throughout the Third Reich era, Furtwängler's eminent influence on Europe's musical life never diminished.

Cultural Vitality

For Americans conditioned to believe that nothing of real cultural or artistic merit was produced in Germany during the Hitler era, the phrase "Nazi art" is an oxymoron -- a contradiction in terms. The reality, though, is not so simple, and it is gratifying to note that some progress is being made to set straight the historical record.

This is manifest, for example, in the publication in recent years of two studies that deal extensively with Furtwängler, and which generally defend his conduct during the Third Reich: The Devil's Music Master by Sam Shirakawa [reviewed in the Jan.-Feb. 1994 Journal, pp. 41-43] and Trial of Strength by Fred K. Prieberg. These revisionist works not only contest the widely accepted perception of the place of artists and arts in the Third Reich, they express a healthy striving for a more factual and objective understanding of the reality of National Socialist Germany.

Prieberg's Trial of Strength concentrates almost entirely on Furtwängler's intricate dealings with Goebbels, Göring, Hitler and various other figures in the cultural life of the Third Reich. In so doing, he demonstrates that in spite of official measures to "coordinate" the arts, the regime also permitted a surprising degree of artistic freedom. Even the anti-Jewish racial laws and regulations were not always applied with rigor, and exceptions were frequent. (Among many instances that could be cited, Leo Blech retained his conducting post until 1937, in spite of his Jewish ancestry.) Furtwängler exploited this situation to intervene successfully in a number of cases on behalf of artists, including Jews, who were out of favor with the regime. He also championed Paul Hindemith, a "modern" composer whose music was regarded as degenerate.

The artists and musicians who left the country (especially the Jewish ones) contended that without them, Germany's cultural life would collapse. High culture, they and other critics of Hitler and his regime arrogantly believed, would wither in an ardently nationalist and authoritarian state. As Prieberg notes: "The musicians who emigrated or were thrown out of Germany from 1933 onwards indeed felt they were irreplaceable and in consequence believed firmly that Hitler's Germany would, following their departure, become a dreary and empty cultural wasteland. This would inevitably cause the rapid collapse of the regime."

Time would prove the critics wrong. While it is true that the departure of such artists as Fritz Busch and Bruno Walter did hurt initially (and dealt a blow to German prestige), the nation's most renowned musicians -- including Richard Strauss, Carl Orff, Karl Böhm, Hans Pfitzner, Wilhelm Kempff, Elizabeth Schwarzkopf, Herbert von Karajan, Anton Webern, as well as Furtwängler -- remained to produce musical art of the highest standards. Regardless of the emigration of a number of Jewish and a few non-Jewish artists, as well as the promulgation of sweeping anti-Jewish restrictions, Germany's cultural life not only continued at a high level, it flourished.

The National Socialists regarded art, and especially music, as an expression of a society's soul, character and ideals. A widespread appreciation of Germany's cultural achievements, they believed, encouraged a joyful national pride and fostered a healthy sense of national unity and mission. Because they regarded themselves as guardians of their nation's cultural heritage, they opposed liberal, modernistic trends in music and the other arts, as degenerate assaults against the cultural-spiritual traditions of Germany and the West.

Acting swiftly to promote a broad revival of the nation's cultural life, the new National Socialist government made prodigious efforts to further the arts and, in particular, music. As detailed in two recent studies (Kater's The Twisted Muse and Levi's Music in the Third Reich), not only did the new leadership greatly increase state funding for such important cultural institutions as the Berlin Philharmonic and the Bayreuth Wagner Festival, it used radio, recordings and other means to make Germany's musical heritage as accessible as possible to all its citizens.

As part of its efforts to bring art to the people, it strove to erase classical music's snobbish and "class" image, and to make it widely familiar and enjoyable, especially to the working class. At the same time, the new regime's leaders were mindful of popular musical tastes. Thus, by far most of the music heard during the Third Reich era on the radio or in films was neither classical nor even traditional. Light music with catchy tunes -- similar to those popular with listeners elsewhere in Europe and in the United States -- predominated on radio and in motion pictures, especially during the war years.

The person primarily responsible for implementing the new cultural policies was Joseph Goebbels. In his positions as Propaganda Minister and head of the "Reich Culture Chamber," the umbrella association for professionals in cultural life, he promoted music, literature, painting and film in keeping with German values and traditions, while at the same time consistent with popular tastes.

Hitler's Attitude

No political leader had a keener interest in art, or was a more enthusiastic booster of his nation's musical heritage than Hitler, who regarded the compositions of Beethoven, Wagner, Bruckner and the other German masters as sublime expressions of the Germanic "soul."

Hitler's reputation as a bitter, second rate "failed artist" is undeserved. As John Lukacs acknowledges in his recently published work, The Hitler of History (pp. 70-72), the German leader was a man of real artistic talent and considerable artistic discernment.

We perhaps can never fully understand Hitler and the spirit behind his political movement without knowing that he drew great inspiration from, and identified with, the heroic figures of European legend who fought to liberate their peoples from tyranny, and whose stories are immortalized in the great musical dramas of Wagner and others.

This was vividly brought out by August Kubizek, Hitler's closest friend as a teenager and young man, in his postwar memoir (published in the US under the title The Young Hitler I Knew). Kubizek describes how, after the two young men together attended for the first time a performance in Linz of Wagner's opera "Rienzi," Hitler spoke passionately and at length about how this work's inspiring story of a popular Roman tribune had so deeply moved him. Years later, after he had become Chancellor, he related to Kubizek how that performance of "Rienzi" had radically changed his life. "In that hour it began," he confided.

Hitler of course recognized Furtwängler's greatness and understood his significance for Germany and German music. Thus, when other officials (including Himmler) complained of the conductor's nonconformity, Hitler overrode their objections. Until the end, Furtwängler remained his favorite conductor. He was similarly indulgent toward his favorite heldentenor, Max Lorenz, and Wagnerian soprano Frida Leider, each of whom was married to a Jew. Their cultural importance trumped racial or political considerations.

Postwar Humiliations

A year and a half after the end of the war in Europe, Furtwängler was brought before a humiliating "denazification" tribunal. Staged by American occupation authorities and headed by a Communist, it was a farce. So much vital information was withheld from both the tribunal and the defendant that, Shirakawa suggests, the occupation authorities may well have been determined to "get" the conductor.

In his closing remarks at the hearing, Furtwängler defiantly defended his record:

The fear of being misused for propaganda purposes was wiped out by the greater concern for preserving German music as far as was possible ... I could not leave Germany in her deepest misery. To get out would have been a shameful flight. After all, I am a German, whatever may be thought of that abroad, and I do not regret having done it for the German people.

Even with a prejudiced judge and serious gaps in the record, the tribunal was still unable to establish a credible case against the conductor, and he was, in effect, cleared.

A short time later, Furtwängler was invited to assume direction of the Chicago Symphony. (He was no stranger to the United States: in 1927-29 he had served as visiting conductor of the New York Philharmonic.)

On learning of the invitation, America's Jewish cultural establishment launched an intense campaign -- spearheaded by The New York Times, musicians Artur Rubinstein and Vladimir Horowitz, and New York critic Ira Hirschmann -- to scuttle Furtwängler's appointment. As described in detail by Shirakawa and writer Daniel Gillis (in Furtwängler and America) the campaigners used falsehoods, innuendos and even death threats.

Typical of its emotionally charged rhetoric was the bitter reproach of Chicago Rabbi Morton Berman:

Furtwängler preferred to swear fealty to Hitler. He accepted at Hitler's hands his reappointment as director of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. He was unfailing in his service to Goebbels' ministry of culture and propaganda ... The token saving of a few Jewish lives does not excuse Mr. Furtwängler from official, active participation in a regime which murdered six million Jews and millions of non-Jews. Furtwängler is a symbol of all those hateful things for the defeat of which the youth of our city and nation paid an ineffable price.

Among prominent Jews in classical music, only the famous violinist Yehudi Menuhin defended the German artist. After Furtwängler was finally obliged to withdrew his name from consideration for the Chicago post, a disillusioned Moshe Menuhin, Yehudi's father, scathingly denounced his co-religionists. Furtwängler, he declared,

was a victim of envious and jealous rivals who had to resort to publicity, to smear, to calumny, in order to keep him out of America so it could remain their private bailiwick. He was the victim of the small fry and puny souls among concert artists, who, in order to get a bit of national publicity, joined the bandwagon of professional idealists, the professional Jews and hired hands who irresponsibly assaulted an innocent and humane and broad-minded man ...

A Double Standard

Third Reich Germany is so routinely demonized in our society that any acknowledgment of its cultural achievements is regarded as tantamount to defending "fascism" and that most unpardonable of sins, anti-Semitism. But as Professor John London suggests (in an essay in The Jewish Quarterly, "Why Bother about Fascist Culture?," Autumn 1995), this simplistic attitude can present awkward problems:

Far from being a totally ugly, unpopular, destructive entity, culture under fascism was sometimes accomplished, indeed beautiful ... If you admit the presence, and in some instances the richness, of a culture produced under fascist regimes, then you are not defending their ethos. On the other hand, once you start dismissing elements, where do you stop?

In this regard, is it worth comparing the way that many media and cultural leaders treat artists of National Socialist Germany with their treatment of the artists of Soviet Russia. Whereas Furtwängler and other artists who performed in Germany during the Hitler era are castigated for their cooperation with the regime, Soviet-era musicians, such as composers Aram Khachaturian and Sergei Prokofiev, and conductors Evgeny Svetlanov and Evgeny Mravinsky -- all of whom toadied to the Communist regime in varying degrees -- are rarely, if ever, chastised for their "collaboration." The double standard that is clearly at work here is, of course, a reflection of our society's obligatory concern for Jewish sensitivities.

The artist and his work occupy a unique place in society and history. Although great art can never be entirely divorced from its political or social environment, it must be considered apart from that. In short, art transcends politics.

No reasonable person would denigrate the artists and sculptors of ancient Greece because they glorified a society that, by today's standards, was hardly democratic. Similarly, no one belittles the builders of medieval Europe's great cathedrals on the grounds that the social order of the Middle Ages was dogmatic and hierarchical. No cultured person would disparage William Shakespeare because he flourished during England's fervently nationalistic and anti-Jewish Elizabethan age. Nor does anyone chastise the magnificent composers of Russia's Tsarist era because they prospered under an autocratic regime. In truth, mankind's greatest cultural achievements have most often been the products not of liberal or egalitarian societies, but rather of quite un-democratic ones.

A close look at the life and career of Wilhelm Furtwängler reveals "politically incorrect" facts about the role of art and artists in Third Reich Germany, and reminds us that great artistic creativity and achievement are by no means the exclusive products of democratic societies.

Bibliography

Gillis, Daniel. Furtwängler and America. Palo Alto: Rampart Press, 1970

Kater, Michael H. The Twisted Muse: Musicians and Their Music in the Third Reich. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997

Levi, Erik. Music in the Third Reich. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1994

Prieberg, Fred K. Trial of Strength: Wilhelm Furtwängler in the Third Reich. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1994

Shirakawa, Sam H. The Devil's Music Master: The Controversial Life and Career of Wilhelm Furtwängler. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992

A Note on Wartime Recordings

Among the most historically fascinating and sought-after recordings of Wilhelm Furtwängler performances are his live wartime concerts with the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonic orchestras. Many were recorded by the Reich Broadcasting Company on magnetophonic tape with comparatively good sound quality. Music & Arts (Berkeley, California) and Tahra (France) have specialized in releasing good quality CD recordings of these performances. Among the most noteworthy are:

Beethoven, Third "Eroica" Symphony (1944) -- Tahra 1031 or Music & Arts CD 814

Beethoven, Fifth Symphony (1943) -- Tahra set 1032/33, which also includes Furtwängler's performances of this same symphony from 1937 and 1954.

Beethoven, Ninth "Choral" Symphony (1942) -- Music & Arts CD 653 or Tahra 1004/7.

Brahms, Four Symphonies -- Music & Arts set CD 941 (includes two January 1945 performances, Furtwängler's last during the war).

Bruckner, Fifth Symphony (1942) -- Music & Arts CD 538

Bruckner, Ninth Symphony (1944) -- Music & Arts CD 730 (also available in Europe on Deutsche Gramophon CD, and in the USA as an import item).

R. Strauss, "Don Juan" (1942), and Four Songs, with Peter Anders (1942), etc. -- Music & Arts CD 829.

Wagner, "Die Meistersinger:" Act I, Prelude (1943), and "Tristan und Isolde:" Prelude and Liebestod (1942), etc. -- Music & Arts CD 794.

Wagner, "Der Ring des Nibelungen," excerpts from "Die Walküre" and "Gotterdämmerung" -- Music & Arts set CD 1035 (although not from the war years, these 1937 Covent Garden performances are legendary)

"Great Conductors of the Third Reich: Art in the Service of Evil" is a worthwhile 53-minute VHS videocassette produced by the Bel Canto Society (New York). Released in 1997, it is distributed by Allegro (Portland, Oregon). It features footage of Furtwängler conducting Beethoven's Ninth Symphony for Hitler's birthday celebration in April 1942. He is also shown conducting at Bayreuth, and leading a concert for wounded soldiers and workers at an AEG factory during the war. Although the notes are highly tendentious, the rare film footage is fascinating.

About the author:

Antony Charles is the pen name of an educator and writer who holds both a master's and a doctoral degree in history. He has taught history and is the author of several books. A resident of North Carolina, he currently works for a government agency.

Reproduced From: The Institute of Historical Review

00:06 Publié dans Musique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : allemagne, musique, années 30, années 40, troisième reich |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook