“We would like women to remain women in their nature, in the whole of their lives, in the aim and fulfilment of these lives, just as we likewise wish men to remain men in their nature and in the aim and fulfilment of their nature and their aims.”—Adolf Hitler

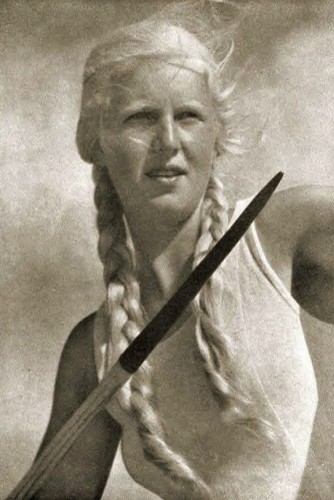

National Socialism promoted two images of woman: the hardworking peasant mother in traditional dress, and the uniformed woman in service to her people. Both images were an attempt to combat two types of woman that are foreign to Traditional European societies: the Aphrodisian and Amazonian woman.

National Socialism promoted two images of woman: the hardworking peasant mother in traditional dress, and the uniformed woman in service to her people. Both images were an attempt to combat two types of woman that are foreign to Traditional European societies: the Aphrodisian and Amazonian woman.

To understand the implications of these types, we must first outline J. J. Bachofen’s theory of the phases of human development and their relation to the Traditionalism of Julius Evola, who translated Bachofen’s Das Mutterrecht (Mother Right) into Italian and wrote the introduction. Bachofen posited a progressive view of history. The earliest and most primitive civilizations were earth-based, what Bachofen called “hetaerist-aphroditic,” since they were characterized by promiscuity.

As a revolt against the mistreatment of women in these early societies, Bachofen determined, agricultural-based Demetrian societies were developed. This phase of development was matriarchal, and exalted woman in her role of wife and mother, since it viewed woman and the earth as sources of generation.

Next, patriarchy developed, in which the sun and man were seen as the source of life. States of consciousness, correspondingly, went beyond the earth and the moon in solar-oriented societies.

Bachofen also outlined several regressions within his system. The cult of Dionysus was a regression from a Demetrian back into an earth-based cult, as exemplified by its emphasis on the vine (i.e., earth), a drunken dissolution into nature, and the promiscuous maenads who were its followers. Another regression was found in the various examples of Amazonian women in Western history, who did away with the need for a male principle.

Evola said that he integrated Bachofen’s ideas in “a wider and more up-to-date order of ideas.” [1]. He posits the Arctic cycle of the Golden Age as the primordial tradition. Demetrian societies came later, and eventually declined into Amazonian and Aphrodisian cycles. Meanwhile, there were descents into Titanic and Dionysian cycles, with a brief revival of the Northern spirit in the heroic age. Although Evola and Bachofen disagreed about the primacy of the Northern tradition, their interpretations of Aphroditism and other degenerations are similar.

As an earth-based society, the Aphrodisian is entirely focused on the material world. These societies are ruled by “the natural law (ius naturale) of sex motivated by lust, and with no understanding of the relationship of intercourse to conception.” [2] Even the afterlife is viewed not as an ascent to a heaven, but a return to nature. Bachofen describes woman’s status in these cultures as the lowest—she is only a sex object, the property of the tribal chief or any man who wants her. Evola’s interpretation is that in Aphrodisian societies, it is man’s status that is the lowest, since woman is the “sovereign of the man who is merely slave of his senses and sexuality, merely the ‘telluric’ being that finds its rest and its ecstasy only in the woman.” [3] Whether interpreting Aphrodisian societies as degrading to men, women, or both, one aspect is clear: Such a worldview emphasizes the lower aspects of sex, and presents woman as an object of base lust. Contrasted to this are Demetrian societies, in which monogamy and the love of the wife and mother replace mere lust.

Such Aphrodisian cultures are found only in pre-Aryan and anti-Aryan societies. In the history of the West, Evola theorizes that solar-based societies originally were found throughout Europe. In the more southern areas of Europe, in the timeline of recorded history at least, the solar forces did not withstand opposing forces for long. According to Joseph Campbell, these earth and lunar forces migrated to the Mediterranean from the East, as the Oriental principle was found in the “Aphroditic, Demetrian, and Dionysian legacies of the Sabines and Etruscans, Hellenistic Carthage and, finally, Cleopatra’s Hellenistic Egypt.”[4] Thus, much of what we associate with classical Greece cannot be assumed to be European, but must be interpreted in light of the degenerations that developed from its contact with the East. Rome, according to Evola, was able to ward off the influence of the telluric-maternal cult due to its establishment of a firm political organization that was centered on the virile principles of a solar worldview.

In addition to the spheres of love and family, Aphrodisian societies have far-reaching political implications as well. Earth and lunar cults were not necessarily (in fact, rarely) governed by women, yet like gynaecocracy, they foster “the egalitarism of the natural law, universalism and communism.” The idea is that Aphrodisian, earth-based societies viewed all men as children of one earth. Thus, “any inequality is an ‘injustice’, an outrage to the law of nature.” The ancient orgies, Evola writes, “were meant to celebrate the return of men to the state of nature through the momentary obliteration of any social difference and of any hierarchy.”[5] This also explains why in some cultures, the lower castes practiced tellurian or lunar rites, while solar rites were reserved for the aristocracy.

These were the Aphrodisian elements that had made their way into the Weimar Republic and Third Reich, and which the National Socialists tried to restrain, along with modern Amazonian woman (the unmarried, childless, career woman in mannish dress). The Aphrodite type was represented by the “movie ‘star’ or some similar fascinating Aphrodisian apparition.”[6] In his introduction to the writings of Bachofen, National Socialist scholar Alfred Baeumler wrote that the modern world has all of the characteristics of a gynaecocratic age. In writing about the European city-woman, he says, “The fascinating female is the idol of our times, and, with painted lips, she walks through the European cities as she once did through Babylon.”[7]

These were the Aphrodisian elements that had made their way into the Weimar Republic and Third Reich, and which the National Socialists tried to restrain, along with modern Amazonian woman (the unmarried, childless, career woman in mannish dress). The Aphrodite type was represented by the “movie ‘star’ or some similar fascinating Aphrodisian apparition.”[6] In his introduction to the writings of Bachofen, National Socialist scholar Alfred Baeumler wrote that the modern world has all of the characteristics of a gynaecocratic age. In writing about the European city-woman, he says, “The fascinating female is the idol of our times, and, with painted lips, she walks through the European cities as she once did through Babylon.”[7]

(PICTURE: Hungarian-born singer Marikka Rökk)

The Nazis’ attempts to combat the Aphrodisian type of woman were manifest in various campaigns and in the writings of Nazi leaders. Most prominent was the promotion of the Gretchen type (the Demetrian woman, in her role as mother and wife), and the discouragement of anything that encouraged the fall of woman into a sex toy rather than a partner for men. Primary emphasis was placed on the discouragement of provocative dress, makeup, and unnatural hair, all which have associations with earth-based cults from the East. According to Evola, the Jewish spirit emphasizes the materialist and sensualist sides of life, with the body viewed as a material instrument of pleasure rather than an instrument of the spirit. Thus, ideologies such as cosmopolitanism, egalitarianism, materialism, and feminism are prevalent in a society that has a worldview infused with a Semitic spirit.[8]

Evola categorized the Aryan spirit as solar and virile, and the Jewish spirit as lunar and feminine. Using Bachofen’s classification system, the latter classifies most easily with Aphrodisian and earth-based cultures — where woman-as-sex-object prevails over woman-as-mother. In fact, there were various versions of “royal Asian women with Aphrodisian features, above all in ancient civilizations of Semitic stock.”[9] A review of archaeological evidence of Aryan and Semitic peoples reveals that, indeed, the only records of Aphrodisian culture in the West (as determined by a culture’s molding of woman into a sex object through fashion, makeup, and the idea of unnatural beauty) are the result of Eastern influence.

Aphrodisian Fashion and Cosmetics Are Absent from the History of Northern Europeans, and Found in Mediterranean Cultures as a Result of Eastern Influence

European civilizations unanimously associated unnatural beauty, achieved by cosmetics and dyed hair, with the lowest castes. This is because in Traditional societies, “health” was a symbol of “virtue” — to feign health or beauty was an attempt to mask the Truth.[10] Although cosmetics and jewelry were used ritually in ancient civilizations, their use eventually degenerated into a purely materialistic function.

The earliest Europeans tended toward simplicity in dress and appearance. Adornments were used solely to signify caste or heroic deeds, or were amulets or talismans. In ancient Greece, jewels were never worn for everyday use, but reserved for special occasions and public appearances. In Rome, also, jewelry was thought to have a spiritual power.[11] Western fashion often was used to display rank, as in Roman patricians’ purple sash and red shoes. The Mediterranean cultures, influenced by the East, were the first to become extravagant in dress and makeup. By the time this influence spread to northern Europe, it had been Christianized, and makeup did not appear again in northern Europe until the fourteenth century, after which followed a long period of its association with immorality.[12]

The earliest Europeans tended toward simplicity in dress and appearance. Adornments were used solely to signify caste or heroic deeds, or were amulets or talismans. In ancient Greece, jewels were never worn for everyday use, but reserved for special occasions and public appearances. In Rome, also, jewelry was thought to have a spiritual power.[11] Western fashion often was used to display rank, as in Roman patricians’ purple sash and red shoes. The Mediterranean cultures, influenced by the East, were the first to become extravagant in dress and makeup. By the time this influence spread to northern Europe, it had been Christianized, and makeup did not appear again in northern Europe until the fourteenth century, after which followed a long period of its association with immorality.[12]

There is no firm evidence, archeological or narrative, for the use of makeup among the Anglo-Saxons. Only one story exists about its use among the Vikings, that of tenth century A.D. traveler Ibrahim Al-Tartushi, who suggested that Vikings in Hedeby (in modern northern Germany) used kohl to protect against the evil eye (obviously an import from the East). Instead of makeup (outside of their often-described war paint), early northern Europeans focused on cleanliness and simplicity, as well as plant-based oils and aromatherapy. Archeological evidence reveals grooming tools for keeping hair tidy and teeth clean, and long hair was an essential beauty element for women.[13] Much of the jewelry worn by Vikings was religious, received as a reward for bravery in battle, or used to fasten clothing (such as brooches).[14]

Ancient Greece and Rome started out similar to northern Europe in the realms of fashion and beauty, but were quickly influenced by the East. Cosmetics were introduced to Rome from Egypt, and become associated with prostitutes and slaves. Prostitutes tended to use more makeup and perfume as they got older, practices that were looked down on as attempts to mask the unpleasant sights and odors of the lower classes. In fact, the Latin lenocinium means both “prostitution” and “makeup.” For a long time, cosmetics also were associated with non-white races, particular those from the Orient. As Rome degenerated, however, the use of makeup spread to many classes, with specialized slaves devoting much time to applying face paint to their masters, especially to lighten the skin color.

Although cosmetics became more accepted in Rome, their use was contrary to Roman beliefs and discouraged in their writings. Romans did not believe in “unnatural embellishment,” but only the preservation of natural beauty, for which there were many concoctions. Such unadulterated beauty was associated with chastity and morality. As an example, the Vestal Virgins did not use makeup. One who did, Postumia, was accused of incestum, a broad category that signifies immoral and irreligious acts.

In addition, Roman men found it suspicious when women tried to appear beautiful: the implications of cosmetic use included a lack of natural beauty, lack of chastity, potential for adultery, seductiveness, unnatural aversion to the traditional roles for women, manipulation, and deceitfulness. The poet Juvenal wrote, “a woman buys scents and lotions with adultery in mind.” Seneca believed the use of cosmetics was contributing to the decline in morality in the Rome Empire, and advised virtuous women to avoid them.[15] The only surviving text from Rome that approves of cosmetics, Ovid’s Medicamina Faciei Femineae (Cosmetics for the Female Face), gives natural remedies for whiter skin and blemishes but extols the virtues of good manners and a good disposition as highest of all beauty treatments.

Originally, the simplest hairstyles were prized in Rome, with women wearing their hair long, often with a headband. Younger girls favored a bun at the nape of the neck, or a knot on top of their head. Elaborate hairstyles only came into fashion during the Roman Empire as it degenerated.[16]

In ancient Greece, as well, makeup was the domain of lower-class women, who attempted to emulate the fair skin of the upper classes who stayed indoors. Rouge was sometimes used to give the skin a healthy and energetic glow. This tradition was continued by women in the Middle Ages, who also valued fair skin.

Cosmetics, dyed hair, and over-accessorizing continued to be associated with loose women as Western society was Christianized. Saint Irenaeus included cosmetics in a list of evils brought to the women who married fallen angels. The early Christian writers Clement of Alexandria, Tatian the Assyrian, and Tertullian also trace the origin of cosmetics to fallen angels.[17]

Dress presents a more difficult area to examine. Although the Nazis associated skimpy dress with foreign elements, this has not always been the case in West. Aryan societies generally did not moralize sex, nor see the body as shameful; women could show a bare breast or wear a short tunic without being viewed as a sex object. In fact, Bachofen reports that more restrictive dress represented a move toward Eastern cultures, which, seeing woman as temptress, insist on extensive covering. According to Plutarch, speaking on the old Dorian spirit:

There was nothing shameful about the nakedness of the virgins, for they were always accompanied by modesty and lechery was banned. Rather, it gave them a taste for simplicity and a care for outward dignity.[18]

Much of these distinctions in beauty treatments can be traced to deeper sources, to the differences in spirit of different peoples. Evola asserts the Roman spirit as the positive side of the Italian people, and the Mediterranean (more influenced by the East) as the negative that needs to be rectified. The first Mediterranean trait is “love for outward appearances and grand gestures”—it is the type that “needs a stage.” In such people, he says, there is a split in the personality: there is “an ‘I’ that plays the role and an ‘I’ that regards his part from the point of view of a possible observer or spectator, more or less as actors do.”

A different kind of split, one that instead supervises one’s conduct to avoid “primitive spontaneity,” is more befitting of the Roman character. The ancient Romans had a model of “sober, austere, active style, free form exhibitionism, measured, endowed with a calm awareness of one’s dignity.” Another negative trait of the Mediterranean type, Evola notes, is individualism, brought about by “the propensity toward outward appearances.” Evola also cites “concern for appearances but with little or no substance” as typical of the Mediterranean type.[19] Such differences in spirit will manifest in the material choices that are inherent to different peoples.

Notes

1. Julius Evola, Revolt Against the Modern World, trans. Guido Stucco (Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions, 1995), 211, footnote.

2. Joseph Campbell, Introduction, Myth, Religion, and Mother Right, by J. J. Bachofen, trans. Ralph Manheim (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967), xxx–xxxi.

3. Evola, “Do We Live in a Gynaecocratic Society?”

4. Campbell, “Introduction” to Bachofen, xlviii.

5. Evola, “Gynaecocratic.”

6. Evola, “Matriarchy in J.J. Bachofen’s Work.”

7. Alfred Baeumler, quoted in Evola, “Matriarchy.”

8. Michael O’Meara, “Evola’s Anti-Semitism.”

9. Evola, “Gynaecocratic.”

10. Evola, Revolt, 102.

11. “Creationism & the Early Church.”

12. “Cosmetics use resurfaces in Middle Ages.”

14. Fiona McDonald,Jewelry And Makeup Through History (Milwaukee, Wis.: Gareth Stevens, 2007), 13.

15. Wikipedia. “Cosmetics in Ancient Rome.”

17. “Creationism & the Early Church.”

18. Plutarch, quoted in Bachofen, 171.

19. Evola, Men Among the Ruins: Post-War Reflections of a Radical Traditionalist, trans. Guido Stucco (Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions, 2002), 260–62.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg The powers threatening our people became hegemonic in May 1945, when the liberal-Communist coalition known as the “United Nations” imposed its dictatorship on defeated Germany.

The powers threatening our people became hegemonic in May 1945, when the liberal-Communist coalition known as the “United Nations” imposed its dictatorship on defeated Germany.

Nazi Fashion Wars:

The Evolian Revolt Against Aphroditism in the Third Reich, Part 2

Judaism is not historically opposed to cosmetics and jewelry, although two stories can be interpreted as negative indictments on cosmetics and too much finery: Esther rejected beauty treatments before her presentation to the Persian king, indicating that the highest beauty is pure and natural; and Jezebel, who dressed in finery and eye makeup before her death, may the root of some associations between makeup and prostitutes.

In most cases, however, Jewish views on cosmetics and jewelry tend to be positive and indicate woman’s role as sexual: “In the rabbinic culture, ornamentation, attractive dress and cosmetics are considered entirely appropriate to the woman in her ordained role of sexual partner.” In addition to daily use, cosmetics also are allowed on holidays on which work (including painting, drawing, and other arts) are forbidden; the idea is that since it is pleasurable for women to fix themselves up, it does not fall into the prohibited category of work.[1]

In addition to the historical distinctions between cultures on cosmetics, jewelry, and fashion, the modern era has demonstrated that certain races enter industries associated with the Aphrodisian worldview more than others. Overwhelmingly, Jews are overrepresented in all of these arenas. Following World War I, the beauty and fashion industries became dominated by huge corporations, many of the Jewish-owned. Of the four cosmetics pioneers — Helena Rubenstein, Elizabeth Arden, Estée Lauder (née Mentzer), and Charles Revson (founder of Revlon) — only Elizabeth Arden was not Jewish. In addition, more than 50 percent of department stores in America today were started or run by Jews. (Click here for information about Jewish department stores and jewelers, and here for Jewish fashion designers).

Hitler was not the only one who noticed Jewish influence in fashion and thought it harmful. Already in Germany, a belief existed that Jewish women were “prone to excess and extravagance in their clothing.” In addition, Jews were accused of purposefully denigrating women by designing immoral, trashy clothing for German women.[2] There was an economic aspect to the opposition of Jews in fashion, as many Germans thought them responsible for driving smaller, German-owned clothiers out of business. In 1933, an organization was founded to remove Jews from the Germany fashion industry. Adefa “came about not because of any orders emanating from high within the state hierarchy. Rather, it was founded and membered by persons working in the fashion industry.”[3] According to Adefa’s figures, Jewish participation was 35 percent in men’s outerwear, hats, and accessories; 40 percent in underclothing; 55 percent in the fur industry; and 70 percent in women’s outerwear.[4]

Although many Germans disliked the Jewish influence in beauty and fashion, it was recognized that the problem was not so much what particular foreign race was impacting German women, but that any foreign influence was shaping their lives and altering their spirit. The Nazis obviously were aware of the power of dress and beauty regimes to impact the core of woman’s self-image and being. According to Agnes Gerlach, chairwoman for the Association for German Women’s Culture:

Not only is the beauty ideal of another race physically different, but the position of a woman in another country will be different in its inclination. It depends on the race if a woman is respected as a free person or as a kept female. These basic attitudes also influence the clothes of a woman. The southern ‘showtype’ will subordinate her clothes to presentation, the Nordic ‘achievement type’ to activity. The southern ideal is the young lover; the Nordic ideal is the motherly woman. Exhibitionism leads to the deformation of the body, while being active obligates caring for the body. These hints already show what falsifying and degenerating influences emanate from a fashion born of foreign law and a foreign race.[5]

Gerlach’s statements echo descriptions of Aphrodisian cultures entirely: Some cultures view women as a sex object, and elements of promiscuity run through all areas of women’s dress and toilette; Aryan cultures have a broader understanding of the possibilities of the female being and celebrate woman’s natural beauty.

The Introduction of Aphrodisian Elements into Germany and the Beginning of the Fashion Battles

Long before the Third Reich, Germans battled the French on the field of fashion; it was a battle between the Aphrodisian culture that had made its way to France, and the Demetrian placement of woman as a wife and mother. As early as the 1600s, German satirical picture sheets were distributed that showed the “Latin morals, manners, customs, and vanity” of the French as threatening Nordic culture in Germany. In the twentieth century, Paris was the height of high fashion, and as tensions between the two countries increased, the French increased their derogatory characterizations of German women for not being stereotypically Aphrodisian. In 1914, a Parisian comic book presented Germans as “a nation of fat, unrefined, badly dressed clowns.”[6] And in 1917, a French depiction of “Virtuous Germania” shows her as “a fat, large-breasted, mean-looking woman, with a severe scowl on her chubby face.”[7]

Hitler saw the French fashion conglomerate as a manifestation of the Jewish spirit, and it was common to hear that Paris was controlled by Jews. Women were discouraged from wearing foreign modes of dress such as those in the Jewish and Parisian shops: “Sex appeal was considered to be ‘Jewish cosmopolitanism’, whilst slimming cures were frowned upon as counter to the birth drive.”[8] Thus, the Nazis staunch stance against anything French was in part a reaction to the Latin qualities of French culture, which had migrated to the Mediterranean thousands of years earlier, and that set the highest image of woman as something German men did not want: “a frivolous play toy that superficially only thinks about pleasure, adorns herself with trinkets and spangles, and resembles a glittering vessel, the interior of which is hollow and desolate.”[9] Such values had no place in National Socialism, which promoted autarky, frugalness, respect for the earth’s resources, natural beauty, a true religiosity (Christian at first, with the eventual goal to return to paganism), devotion to higher causes (such as to God and the state), service to one’s community, and the role of women as a wife and mother.

Opposition to the Aphrodisian Culture in the Third Reich

Most students of Third Reich history are familiar with the more popular efforts to shape women’s lives: the Lebensborn program for unwed mothers, interest-free loans for marriage and children, and propaganda posters that emphasized health and motherhood. But some of the largest battles in the fight for women occurred almost entirely within the sphere of fashion—in magazines, beauty salons, and women’s organizations.

The Nazis did not discount fashion, only its Aphrodisian manifestations. On the contrary, they understood fashion as a powerful political tool in shaping the mores of generations of women. Fashion and beauty also were recognized as important elements in the cultural revolution that is necessary for lasting political change. German author Stafan Zweig commented on fashion in the 1920s:

Today its dictatorship becomes universal in a heartbeat. No emperor, no khan in the history of the world ever experienced a similar power, no spiritual commandment a similar speed. Christianity and socialism required centuries and decades to win their followings, to enforce their commandments on as many people as a modern Parisian tailor enslaves in eight days.[10]

Thus, Nazi Germany established a fashion bureau and numerous women’s organizations as active forces of cultural hegemony. Gertrud Scholtz-Klink, the national leader of the NS-Frauenschaft (NSF, or National Socialist Women’s League), said the organization’s aim was to show women how their small actions could impact the entire nation.[11] Many of these “small actions” involved daily choices about dress, shopping, health, and hygiene.

The biggest enemies of women, according to the Nazi regime, were those un-German forces that worked to denigrate the German woman. These included Parisian high fashion and cosmetics, Jewish fashion, and the Hollywood image of the heavily made up, cigarette-smoking vamp—the archetype of the Aphrodisian. These forces not only impacted women’s clothing, personal care choices, and activities, but were dangerous since they touched the German woman’s very spirit.

Clothing should not now suddenly return to the Stone Age; one should remain where we are now. I am of the opinion that when one wants a coat made, one can allow it to be made handsomely. It doesn’t become more expensive because of that. . . . Is it really something so horrible when [a woman] looks pretty? Let’s be honest, we all like to see it.[14]

Though understanding the need for tasteful and beautiful dress, the Nazis were adamantly against elements foreign to the Nordic spirit. The list included foreign fashion, trousers, provocative clothing, cosmetics, perfumes, hair alterations (such as coloring and permanents), extensive eyebrow plucking, dieting, alcohol, and smoking. In February 1916, the government issued a list of “forbidden luxury items” that included foreign (i.e., French) cosmetics and perfumes.[15] Permanents and hair coloring were strongly discouraged. Although the Nazis were against provocative clothing in everyday dress, they encouraged sportiness and were certainly not prudish about young girls wearing shorts to exercise. A parallel can be seen in the scanty dress worn by Spartan girls during their exercises, a civilization characterized by its Nordic spirit and solar-orientation.

Some have said that Hitler was opposed to cosmetics because of his vegetarian leanings, since cosmetics were made from animal byproducts. More likely, he retained the same views that kept women from wearing makeup for centuries in Western countries—the innate understanding that the Aphrodisian woman is opposed to Aryan culture. Nazi proponents said “red lips and painted cheeks suited the ‘Oriental’ or ‘Southern’ woman, but such artificial means only falsified the true beauty and femininity of the German woman.”[16] Others said that any amount of makeup or jewelry was considered “sluttish.”[17] Magazines in the Third Reich still carried advertisements for perfumes and cosmetics, but articles started advocating minimal, natural-looking makeup, for the truth was that most women were unable to pull off a fresh and healthy image without a little help from cosmetics.

Although jewelry and cosmetics were not banned, many areas of the Third Reich were impossible to enter unless conforming to Nazi ideals. In 1933, “painted” women were banned from Kreisleitung party meetings in Breslau. Women in the Lebensborn program were not allowed to use lipstick, pluck their eyebrows, or paint their nails.[18] When in uniform, women were forbidden to wear conspicuous jewelry, brightly colored gloves, bright purses, and obvious makeup.[19] The BDM also was influential in shaping fashion in the regime, with young girls taking up the use of clever pejoratives to reinforce the regime’s message that unnatural beauty was not Aryan. The Reich Youth Leader said:

The BDM does not subscribe to the untruthful ideal of a painted and external beauty, but rather strives for an honest beauty, which is situated in the harmonious training of the body and in the noble triad of body, soul, and mind. Staunch BDM members whole-heartedly embraced the message, and called those women who cosmetically tried to attain the Aryan female ideal ‘n2 (nordic ninnies)’ or ‘b3 (blue-eyed, blonde blithering idiots).’[20]

The Nazis offered many alternatives to Aphrodisian values: beauty would be derived from good character, exercise outdoors, a good diet, healthy skin free of the harsh chemicals in makeup, comfortable (yet still stylish and flattering) clothing, and from the love for her husband, children, home, and country. The most encouraged hairstyles were in buns or plaits—styles that saved money on trips to the beauty salon and were seen as more wholesome and befitting of the German character. In fact, Tracht (traditional German dress) was viewed as not merely clothing, but also as “the expression of a spiritual demeanor and a feeling of worth . . . Outwardly, it conveys the expression of the steadfastness and solid unity of the rural community.”[21] Foreign clothing designs, according to Gerlach, led to physical and “psychological distortion and damage, and thereby to national and racial deterioration.”[22]

* * *

Some people may be inclined to interpret Aphrodisian culture as positive for the sexes—it puts the emphasis for women not on careers but on their existence as sexual beings. Men often encourage such behavior by their dating choices and by complimenting an Aphrodisian “look” in women. But Aphrodisian culture is not only damaging to women, as Bachofen relates, by reducing them to the status of sex slave of multiple men. It also is degrading for men, at the level of personality and at the deepest levels of being. As Evola writes about the degeneration into Aphroditism:

The chthonic and infernal nature penetrates the virile principle and lowers it to a phallic level. The woman now dominates man as he becomes enslaved to the senses and a mere instrument of procreation. Vis-à-vis the Aphrodistic goddess, the divine male is subjected to the magic of the feminine principle and is reduced to the likes of an earthly demon or a god of the fecundating waters—in other words, to an insufficient and dark power.[23]

(PICTURE: Swedish singer Zarah Leander)

If someone needs the ‘unusual’ to be moved to astonishment, that person has lost the ability to respond rightly to the wondrous, the mirandum, of being. The hunger for the sensational . . . is an unmistakable sign of the loss of the true power of wonder, for a bourgeois-ized humanity.[24]

A society that promotes so much unnatural beauty will no doubt lose the ability to experience the wondrous in the natural. It is essential that people retain the ability to love and be moved by the pure and natural, in order to once again return to a civilization centered in a Traditional Aryan worldview.

Notes

1. Daniel Boyarin, “Sex,” Jewish Women’s Archive.

2. Irene Guenther, Nazi ‘Chic’?: Fashioning Women in the Third Reich (Oxford: Berg, 2004), 50–51.

(Oxford: Berg, 2004), 50–51.

3. Guenther, 16.

4. Guenther, 159.

5. Agnes Gerlach, quoted in Guenther, 146.

6. Guenther, 21–22.

7. Guenther, 26.

8. Matthew Stibbe, “Women and the Nazi state,” History Today, vol. 43, November 1993.

9. Guenther, 93.

10. Stefan Zweig, quoted in Guenther, 9.

11. Jill Stephenson, Women in Nazi Germany (Essex, UK: Pearson, 2001), 88.

(Essex, UK: Pearson, 2001), 88.

12. Stephenson, 133.

13. Guenther, 120.

14. Adolf Hitler, quoted in Guenther, 141.

15. Guenther, 32.

16. Guenther, 100.

17. Guido Knopp, Hitler’s Women (New York: Routledge, 2003), 231.

(New York: Routledge, 2003), 231.

18. Guenther, 99.

19. Guenther, 129.

20. Guenther, 121.

21. Guenther, 111.

22. Gerlach, quoted in Guenther, 145.

23. Evola, Revolt, 223.

24. Josef Pieper, Leisure: The Basis of Culture , trans. Gerald Malsbary (South Bend, Ind.: St. Augustine’s Press, 1998), 102.

, trans. Gerald Malsbary (South Bend, Ind.: St. Augustine’s Press, 1998), 102.