THE MAIN PROBLEMS OF MODERN HUMAN

I want to start with the question: “Is it possible to become Renaissance Man in the Digital Age?»

The problem of modern human living in the era of Big Data is that he is drowning in the flow of information. The human of Antiquity, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, had a particular amount of knowledge. Today, we can’t even determine what we need to know. Most often, this is determined by our profession and the direction of our activity. Given the fact that the modern world is still dominated by the tendency to narrow specialization, we can come to disappointing conclusions. A modern human needs to be able to find in a massive flow of unstructured information, the one that will serve for its comprehensive and harmonious development.

Nowadays, only a few people know how to work with information. It is not chaotic to absorb, not to be satisfied with an incomplete acquaintance, but to be selective, to show the art of separating important from secondary, necessary from casual. There are two opposite approaches to knowledge: simple accumulation of information and transformation by knowledge. These two approaches are based on two principles — forma formanta and forma informanta. The first is inherent in a person initially. The forma formanta action is directed from the center to the periphery. We can say that this is the inner Logos or axis of the soul. This principle conditions all internal transformations that we experience. Forma formanta is related to “vertical knowledge”. Forma informanta is an external force that acts from the periphery to the center. It determines all other people’s influences (especially the importance of society). This is “horizontal knowledge”. I realized very early on that our entire educational system is based on forma informanta. In educational institutions, we are informed at best, but we are not formed in any way. In the twenty-first century, we have to synthesize these two principles.

There are other problems faced by the modern human, who can no longer imagine his life without digital assistants. According to research conducted by cognitive neurobiologists, people barely read texts. They don’t read anymore; they just scan them. Scattered attention, fragmentary perception of information, search for keywords, “surfing” rather than reading — this is the result. Of course, many people have decided to abandon paper books altogether and wholly switched to electronic ones. The skill of reading is increasingly lost. It is no secret that many people are no longer able to read Hesse’s “The Glass Bead Game “, much less Schelling’s” Philosophy of mythology”. How can we counter the trend outlined here? One of the ways today is called slow read. For this purpose, reading groups are created all over the world. They allow you to experience time differently and reopen text that is not scanned but is slowly read, parsed, discussed, and commented on.

Another problem with a modern human is poor memory. Why remember something if you can find all the information on the Internet? Xenophon reports that Athenian politician and general Nicias forced his son Niceratus to memorize by heart the works of Homer. Now no one even tries to set such a task for themselves. It has reached the point that today not everyone is also able to finish reading the epic of Homer to the end. Alberto Manguel writes in “Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey: A Biography” that memory training in the Byzantine educational system was given considerable attention: after several years of practice, students had to know the Iliad by heart.

Another problem with a modern human is poor memory. Why remember something if you can find all the information on the Internet? Xenophon reports that Athenian politician and general Nicias forced his son Niceratus to memorize by heart the works of Homer. Now no one even tries to set such a task for themselves. It has reached the point that today not everyone is also able to finish reading the epic of Homer to the end. Alberto Manguel writes in “Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey: A Biography” that memory training in the Byzantine educational system was given considerable attention: after several years of practice, students had to know the Iliad by heart.

CREATION A WORLDVIEW

Creation a worldview is a complex and lengthy process. We often meet people who do not have any worldview. At best, they have a particular set of opinions (in most cases, not their own) and incomplete knowledge, based on which they draw conclusions and make decisions. If there is no worldview, then there is no internal axis, center, or reference point around which a separate world is formed. A person “just lives”, unaware of the values, views, and desires imposed on him. The inability to cope with the massive flow of information that today threatens to wash away any truth from the face of the earth leads it to a chaotic capture, senseless accumulation. He does not know how to choose the most important thing from this inexhaustible stream. If he had a worldview, a particular coordinate system, then approaching the bookshelves or looking at a series of links and headlines in his news feed, a person would instantly make the right decision: “take” or “put aside”. To build your worldview, you need to be a good architect.

In the process of forming ourselves, we always lose sight of the fact that human is a process, as the act of creation. It is in constant development and transformation. There is an ontological gap between the human of Antiquity and the human of the Middle ages. And those who naively believe that humans are always the same, that we are the same today as we were hundreds of years ago, make an unforgivable mistake. When we talk about the “ancient Greek,” “medieval European,” “Renaissance human,” “Modern human,” “postmodern individual,” we are talking about entirely different and, I would venture to say more radically, diametrically different human types. Changing paradigms always means a fundamental change that can be correlated with a “re-creation of the world.” Everything changes the ontological status of a human, his view of life, death and the afterlife, time and space, the divine; his ideals, his values, etc. change. The understanding of these changes dictates the division into historical periods.

Joel Barker, in his book “Paradigms: Business of Discovering the Future”, emphasizes that he does not agree with Thomas Kuhn, who believed that paradigms exist only in science. I always emphasize that I use the word “paradigm” without any reference to Kuhn’s paradigm theory, and take its original meaning (from Greek. παράδειγμα, “example, model, sample”). So, Barker is convinced that the new paradigm comes sooner than there is a need for it. The paradigm is always ahead of demand. And, of course, the apparent reaction to this is rejection. Who is changing the paradigm, according to Barker? It’s always an outsider. The one who breaks the rules turns them — at the same time improving the world. “What is defined as impossible today is impossible only in the context of present paradigms,” says Barker. Let’s put the question again: “is it Possible to become Renaissance human in the digital age? This is not possible only in the context of the old paradigm. But that paradigm could disappear by tomorrow.

Joel Barker, in his book “Paradigms: Business of Discovering the Future”, emphasizes that he does not agree with Thomas Kuhn, who believed that paradigms exist only in science. I always emphasize that I use the word “paradigm” without any reference to Kuhn’s paradigm theory, and take its original meaning (from Greek. παράδειγμα, “example, model, sample”). So, Barker is convinced that the new paradigm comes sooner than there is a need for it. The paradigm is always ahead of demand. And, of course, the apparent reaction to this is rejection. Who is changing the paradigm, according to Barker? It’s always an outsider. The one who breaks the rules turns them — at the same time improving the world. “What is defined as impossible today is impossible only in the context of present paradigms,” says Barker. Let’s put the question again: “is it Possible to become Renaissance human in the digital age? This is not possible only in the context of the old paradigm. But that paradigm could disappear by tomorrow.

PARADIGM SHIFT: A REVOLUTION IN HUMAN THINKING

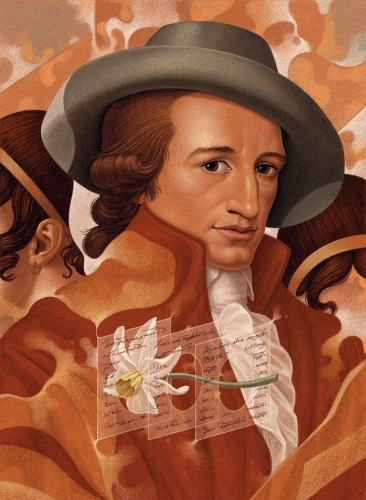

The type of personality that appeared in the pre-Socratic period delighted Friedrich Nietzsche, who wrote about the Republic of Geniuses, where the philosopher was a magician, a king, and a priest. This type of personality will still manifest itself in the Middle ages — in the person of the philosopher, scientist, and theologian Albert the Great (Doctor Universalis), the Arab scientist Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham and the philosopher and naturalist Roger Bacon. And in the Renaissance — as homo univeralis, the most striking embodiment of which will be Leonardo da Vinci: painter, sculptor, architect, inventor, musician, writer, and scientist, ahead of his time. Then it will be replaced by another type-a a scientist of narrow specialization. It’s no longer a microcosm that reflects the entire universe (macrocosm). The world becomes too vast for him, so the specialist decides to confine himself to a small island, where he spends the rest of his days in the eternal scientific studies, to come to results that can easily be refuted by a new generation of such scientists. E. R. Dodds wrote:

The sort of specialisation we have today was quite unknown to Greek science at any period, and some of the greatest names at all periods are those of nonspecialists, as may be seen if you be seen if you look at a list of the works of Theophrastus or Eratosthenes, Posidonius, Galen, or Ptolemy.

In the age of Antiquity, the idea of a perfect human necessarily included the concept of “kalokagathos” (Ancient Greek: καλὸς κἀγαθός). It was a symbol of the harmonious union of external and internal virtues. Another idea that will become the basis of the system of classical education — “Paideia” (παιδεία), that is, the formation of a holistic personality, it was closely related to “kalokagathos.” The harmonious system of ancient (classical) education laid the foundation for the future educational system of Europe.

For the ancient Greeks, the human was not just an individual but an idea. And this idea included all stages of the spiritual and intellectual development of society.

In the Middle Ages, the concept of the ideal human changes significantly, and in place of harmony between external and internal comes the realization of the original sinfulness of the human being; between God and human, an abyss appears, forcing the latter to take the path of redemption to restore the lost harmony. The flesh begins to be thought of as sinful and despicable, the earthly world as a place that must to reject and devote all your thoughts to the service of God. Knowledge gives way to faith. An ascetic monk takes the place of the ancient Greek. The fundamental idea of” imitating God” remains unchanged, only God and the nature of the imitation itself change. If the ancient Greeks imitated the Olympian gods and heroes, the medieval human imitated Christ. The changes in human perception of the world during the transition from Antiquity to the Middle Ages are so radical that at the time we are talking not just about two different ideas about the “perfect human”, but also about two different ontological levels: “the level of the Mystery” and “the level of baptized”. In both cases, the person experienced profound changes, after which his life was strictly divided into “before” and “after”. It is no coincidence that Hans Sedlmayr begins the periodization of Western culture from the Middle ages (skipping Antiquity) — it was another world, another human, another ideal, another look at the choice of life, a different view of death. And another way of looking at philosophy. For a medieval human, philosophy was “the handmaiden of theology.”

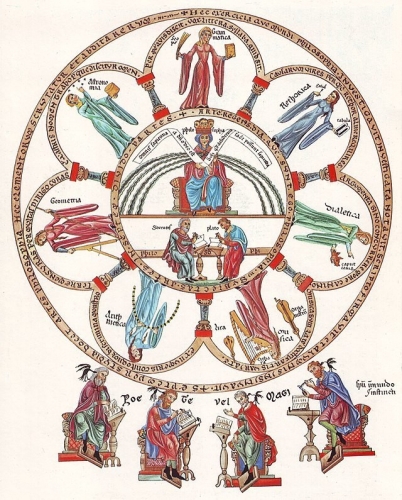

It was in the middle ages that the first universities began to appear, which immediately acquired the status of centers of philosophy and culture, science, and education. As a rule, the medieval University consisted of three higher faculties: theology, medicine, and law. Before entering one of these faculties, the student was trained at the artistic (preparatory) faculty, where he studied seven Liberal arts. And only after receiving the title of bachelor or master, he had the right to enter one of the three faculties, were at the end of the training, he won the title of doctor of law, medicine or theology. The seven Liberal arts were divided into two cycles: trivium (grammar, dialectics (logic), rhetoric) and quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, music, or harmonica). Despite the fact that the origins of the seven Liberal arts go back to the Hellenistic era (the Sophist Hippias), in the Middle ages this system was in the service of religion: grammar was intended for the interpretation of Church books, dialectics was used for polemics with heretics, rhetoric was necessary as a tool for creating religious sermons, etc.

Only in the Renaissance age (which was primarily the Renaissance of Antiquity) does the medieval idea of a sinful being give way to the idea of homo universalis, a harmonious and holistic personality; inevitably this means a return to the fundamental principles of the Ancient idea of the perfect human — “kalokagathos”, “paideia”, “arete”. After Thomas Aquinas and Saint Augustine of Hippo come to Georgius Gemistus, Marsilio Ficino and Pico Della Mirandola. Classical education, based on the study of ancient languages as a way to comprehend the cultural heritage of Antiquity, was founded in this era. As the Russian poet and playwright Vyacheslav Ivanovich Ivanov rightly remarked: “European thought constantly and naturally returns for new stimuli to the genius of Greece.”

In the Renaissance, a paradigm shift occurs again: appear is a gap between the medieval worldview and the worldview of the Renaissance human. The same gap to separate the person of the Renaissance from the individual of the New time when there was a break with the classical model of education. One of the embodiments of the anti-classical approach to education was the French sociologist Jean Fourastie (1909–1990), who insisted that we should discard the classical humanitarian culture and focus on the new ideal of an educated person — a specialist of a narrow profile who has the ability to quickly adapt to the constantly changing realities of the modern world. This specialist was not required to have a high level of culture since the range of his tasks was reduced to the effective service of the world, the values of which were now determined not by homo universalis, but by homo economicus.

REINVENTION OF HUMAN

Today it is common to talk about the collapse of humanism, but we still use the word “humanitarian” out of habit. What is humanitas, and does the range of modern Humanities correspond to its original purpose? Why do we observe how the very “idea of human” is lost? “The Fatigue from human”, “the overthrow of the human”, “the destruction of the human”, “the disappearance of the human” arise in all spheres of our existence.

The latest trends in modern thought reduce a person to the level of an object, depriving him of his prior ontological status. A toothpick and a Buddhist monk, a Hummer and a Heidegger, a nail file, and a talented painter are placed on the same line. One is equal to the other. Object-oriented thinking that puts a THING at the center of being. Metaphysics of things. Being is no longer hierarchical. The same tendency can be found in modern theater and in contemporary painting, which is looking for an opportunity to free themselves from a human finally. Objects and things are increasingly taking the place of the human. The human himself, sometimes installed in work, turns into an object. The human image “disintegrates”, is dismembered, disassembled into parts, like a mechanism. In painting, there has long been a fragmentation of the human image (from distortion of proportions and emphasis on bodily ugliness to the dismemberment of the body). At Norwegian artist Odd Nerdrum, the focus on painful and damaged bodies becomes constant. American artist and sculptor Sarah Sitkin is engaged in splitting the human image, deliberately distorting it. We can see the same thing in the works of other artists: Marcello Nitti, Radu Belchin, Christian Zucconi, Berlinde de Bruyckere, Emil Alzamora, João Figueiredo.

The human is almost banished. But in his place did not come, neither a Superman nor a Godman. Rare attempts to put a different anthropological formation in the position of the disappearing human can be noticed even among European symbolists: Jean Delville, Simeon Solomon, Fernand Khnopff, Emile Fabry, and others. But this was instead a warning of the” new human,” his barely perceptible breath, a secret call. Science fiction writers (for example, Herbert Wells) managed to anticipate the phenomenon of its complete opposite — Digital Human. Who is he, this child of the network century, communicating through tags and tweets — a harbinger of the end of humanity or the Creator of a new “Digital God” — Artificial Intelligence? All attempts by inhumanists, speculative realists, “space pessimists”, etc. to solve the problem of “Lost Centre” and learn to think beyond the limits of human are initially doomed to failure. They do not create breakthroughs in the field of thought; all they do is reveal the symptoms of a dangerous disease called “death of the idea of human”.

I am convinced that the crisis of the Humanities is connected with the plight of the “idea of the human.” And only a return to the “idea of human”, to the spiritual dimension of human existence, but at a new stage, can lead to the revival of the Humanities. In this and only in this case will humanitas regain its original meaning. However, it is not enough just to go back to the old definition of human, today we have to “reinvention of human”. Redefine its meaning, redefine its purpose and place in the world, and understand its advantages over Artificial Intelligence.

Tobias Rees is the founding Director of the Institute’s Transformations of the Human Program. He suggests that fields such as Artificial Intelligence and synthetic biology should be seen as philosophical and artistic laboratories where new concepts of human, politics, understanding of nature, and technology are formed. What was traditionally associated with the main tasks of the Humanities, which were centered on human, has now moved to the fields of natural and technical sciences. The Humanities have stopped answering the question: “What is a human?” But this is the fundamental and critical issue today. Specialists who are closed within the boundaries of their disciplines are not able to answer it. Tobias Rees sends philosophers and artists to the world’s largest corporations to work with engineers and technologists to form a new idea of the human.

Tobias Rees is the founding Director of the Institute’s Transformations of the Human Program. He suggests that fields such as Artificial Intelligence and synthetic biology should be seen as philosophical and artistic laboratories where new concepts of human, politics, understanding of nature, and technology are formed. What was traditionally associated with the main tasks of the Humanities, which were centered on human, has now moved to the fields of natural and technical sciences. The Humanities have stopped answering the question: “What is a human?” But this is the fundamental and critical issue today. Specialists who are closed within the boundaries of their disciplines are not able to answer it. Tobias Rees sends philosophers and artists to the world’s largest corporations to work with engineers and technologists to form a new idea of the human.

At the same time, we must clearly understand that rethinking the idea of the human will undoubtedly entail a rethinking of the entire corpus of Humanities. What is it like to be a human being in the age of intelligent machines? What is the fundamental advantage of a human? What will never, under any circumstances, be impossible to automate, calculate, and turn into Algorithms? Futurologist Gerd Leonhard, contrary to Yuval Harari, who is obsessed with Algorithms, puts forward the idea of androrithms, that is, specific non-enumerable attributes that make us humans. These attributes are exclusively human and can never be assigned by a machine. To androrithms, Leonhard includes empathy, intuition, compassion, emotional intelligence, imagination, and Dasein (Heidegger). Leonhard writes:

«Leonardo Da Vinci’s ‘Vitruvian Man’ depicted the ideal proportions of the human body — maybe now we need a ‘neoluvian man’ describing the future relationship of humans and technology?».

In the article “2020 Will Bring A New Renaissance: Humanity Over Technology”, Gerd Leonhard argues that we will soon witness a resurgence of humanism and the Humanities. Undoubtedly, this trend is gradually gaining influence in the Western world. It is enough to read the book “Sensemaking: The Power of the Humanities in the Age of the Algorithm” by Christian Madsbjerg to see how modern world leaders and corporate heads are rediscovering the Humanities and applying its methods to solve critical problems in their industry. Madsbjerg himself is a well-known business consulting specialist and founder of ReD Associates. He founded a consulting company when he was only 22 years old and developed an innovative approach to business thinking (his company specializes in strategic consulting based on the foundation of the Humanities). He is a genuine Polymath that has a dominant intellectual (theoretical and practical) foundation in the field of philosophy, Ethnography, anthropology, sociology, literary studies, history, discursive analysis, business management, etc.

You might be surprised to find that more than a third of Fortune 500 CEOs have degrees in the Humanities. The illusory idea that only a narrow specialization in STEM will give us a guarantee of building a successful career is a thing of the past. Even the Israeli historian Yuval Harari was forced to admit that the development of AI can displace many people from the labor market. Still, at the same time, there will be new jobs for philosophers. It is their skills and knowledge that will suddenly be in high demand. And American billionaire Mark Cuban believes that “In 10 years, a liberal arts degree in philosophy will be worth more than a traditional programming degree.”

We live in the age of Big Data, but we need to remember that Big Data will never replace Big Ideas. It is the absence of Big Ideas that can be considered the main characteristic of the modern era. Big Ideas always carry transformational potential, imply radical transformations, and those who dare to express them, as a rule, are tested by distrust on the part of a society that is not ready for changes. But only these people have had and will continue to have an impact on the course of human history — Renaissance human, polymath — the Big Idea that underlies the new paradigm of thinking. If you need to define this type of thinking, the most appropriate epithet for it is “integrative”. Roger Martin limits it’s as “the ability to face constructively the tension of opposing ideas and, instead of choosing one at the expense of the other, generate a creative resolution of the tension in the form of a new idea that contains elements of the opposing ideas but is superior to each.” Most people are used to thinking in the “or-or” mode; it is difficult for them to keep two mutually exclusive ideas in their heads at the same time and, without throwing either of them away, to generate a new one (and this process involves intelligence, intuition and every time a unique human experience).

They also find it challenging to create a synthesis of knowledge and skills from different disciplines, and the implementation of integration of various industries seems almost fantastic to them.

I want to emphasize that this is not just about one type of thinking. It is a critical meta-skill that is a human advantage and will never be mastered by a machine, despite the development that Artificial Intelligence will soon achieve.

Strictly speaking, today, we can distinguish three main types of thinking: algorithmic (machine), traditional and integrative (holistic). In the age of Algorithms, only integrative thinking can withstand the battle with AI. The struggle is not just for resources, power, or influence, but for a human.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg