Cola di Rienzi & the Politics of Proto-Fascism

Ronald F. Musto

Apocalypse in Rome:

Cola di Rienzo and the Politics of the New Age

Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003

A young Italian nationalist leads his followers on a march through Rome, seizing power from corrupt elites to establish a palingenetic regime. Declaring himself Tribune, his ultimate aim is to recreate the power and glory of Ancient Rome. However, a conspiracy of his enemies topples him from power, and he is imprisoned. Eventually, the most powerful man in the West frees him and restores him to power — albeit as leader of a puppet regime. His second attempt at Italian rebirth is cut short; he is captured, killed, and his body desecrated by the howling mob. A man who had attempted to drive his degenerate countrymen to fulfill a higher destiny is cut down by the unthinking masses — a cowardly herd who lacked the ability to comprehend, much less work towards, this leader’s dreams of glory.

A young Italian nationalist leads his followers on a march through Rome, seizing power from corrupt elites to establish a palingenetic regime. Declaring himself Tribune, his ultimate aim is to recreate the power and glory of Ancient Rome. However, a conspiracy of his enemies topples him from power, and he is imprisoned. Eventually, the most powerful man in the West frees him and restores him to power — albeit as leader of a puppet regime. His second attempt at Italian rebirth is cut short; he is captured, killed, and his body desecrated by the howling mob. A man who had attempted to drive his degenerate countrymen to fulfill a higher destiny is cut down by the unthinking masses — a cowardly herd who lacked the ability to comprehend, much less work towards, this leader’s dreams of glory.

Is this the life of Benito Mussolini, Duce of Fascist Italy? Well, perhaps — but even more accurately it is a description of Il Duce’s predecessor, the Roman notary Cola di Rienzi. In the mid-fourteenth century, 900 years after the Fall of Rome, di Rienzi engaged in a romantic and ill-fated attempt to restore the Roman Republic and, perhaps, the Empire itself. Musto’s book tells us what happened. To those familiar with the life of Mussolini, di Rienzi’s tale is shocking in its similarities — shocking and depressing.

The life of Cola di Rienzi — referred to by Musto as Cola di Rienzo — is well known to historians of the Middle Ages, and was, at one time, well known to Italians in general. But in the twentieth century he was eclipsed by Mussolini, who still symbolizes Roman and Italian renewal in many minds. The self-hating Italian Luigi Barzini did di Rienzi no favors in his book The Italians. Thus, Musto’s sympathetic and well-written biography of di Rienzi is long overdo, and is an excellent addition to the library of any individual interested in European history. Of interest for this essay is the relationship of di Rienzi to fascism and the role played by the church and selfish elites in the downfall of di Rienzi and in the humiliating history of modern Italy.

Roger Griffin (Fascism, Oxford University Press, 1995) famously described fascism as “palingenetic populist ultra-nationalism” — making the elements of renewal, rebirth, and regeneration central to all permutations of this ideology. That Cola di Rienzi was a proto-fascist is quite clear. He was a populist leader, appealing to the middle class against established elites, intent on the regeneration and rebirth of Rome, Italy, and, by example, the world.

That he couched this agenda in highly religious Christian terms is to be expected for the time and place — in fourteenth century Italy he could not do otherwise — and in no way detracts from the fascistic palingenetic tone of his rhetoric and actions. After all, perhaps the “most fascist” of all the twentieth-century fascisms — Romania’s Legionary movement — was devoutly Christian and made spiritual/moral regeneration the palingenetic focus of their ideology. Thus, there is no obvious reason not to see “Rienzism” as a sort of fourteenth century fascism.

Indeed, as Musto describes di Rienzi’s march through Rome (sound familiar?) to establish his buono stato (good state), we read the following : “. . . the people of Rome restored to their proper place, mingling among friends, neighbors, and strangers, all sharing the same sense of rebirth and renewal” (emphasis added). That sounds reasonably palingenetic to me; Cola di Rienzi as Tribune of Rome or Benito Mussolini as Duce of Italy — the similarities outweigh the differences.

That Cola di Rienzi is viewed by many as a generally positive figure who — for all his flaws — sincerely wanted the best for the people suggests that perhaps proto-fascism (or fascism, for that matter) is not the unalloyed evil that some make it out to be.

Musto states that di Rienzi was more of an artist than a politician in his actions and propaganda, which is completely consistent with the aesthetic nature of fascist movements (uniforms, ceremonies, rituals, art, etc.) of the twentieth century. Cola di Rienzi’s friend and admirer was the famed Petrarch, who recognized in the young Tribune the hope of Italy and the possibility of a new age, an age of rebirth and promise. Thus, a primary icon of fourteenth century Western culture was attracted to the sociopolitical and aesthetic characteristics of the Rienzian phenomenon.

Musto notes that di Rienzi spoke not only for the people of Rome but for all the people of “sacred Italy” to whom he wished to extend Roman citizenship. Musto describes in detail how, after spending time with Pope Clement VI — his eventual bitter enemy — di Rienzi returned to Rome to overthrow the feudal rule of the baronial families. These barons had turned the eternal city into a depopulated, anarchical, bloody, and violent mess, with the Roman people groaning under the self-interested misrule of the baronial elite.

Cola spent many months laying the groundwork for his revolution, engaging in various form of propaganda, including art as well as speech, until the day came when he and followers marched to seize power. Cola declared himself Tribune, ousted the barons, and began the formation of the so-called buono stato — a name which implies as much moral/spiritual renewal as much as it does plain good governance.

And di Rienzi did bring good governance; to use twentieth-century language he made the “trains run on time.” Establishing ties with other Italian cities, reaching out to the West as a whole, and supported by Petrarch, di Rienzi captured the attention not only of Europe but also instilled fear into the Islamic world, which saw the possibility of a resurgent Rome as the center of Western resistance to Asiatic expansion.

However, the Pope was not at all pleased with the rise of a secular power base in Rome to challenge the Church. As long as he perceived that di Rienzi would act as an effective mouthpiece to enforce Papal prerogatives against the barons, Clement supported the Tribune. But as soon as it became apparent that di Rienzi was his own man, with his own agenda, and that this agenda included a destiny for Rome and Italy that went beyond slavish subservience to the church, Clement decided that di Rienzi had to go.

Therefore, after months of intriguing against di Rienzi — even to the point of attempting to orchestrate food shortages to turn the Roman people against the Tribune — the Pope (the papacy at this time being self-exiled in France to protect themselves from their secular enemies) dropped the bombshell: on Dec. 3, 1347, Cola di Rienzi was condemned and excommunicated, and all who would support the Tribune were threatened with the same fate.

Indeed, if Rome still rallied behind di Rienzi, the entire city would have been under the Papal interdict; the entire city would have become a pariah in the Western, Christian world. In the fourteenth century, particularly fourteenth century Italy, excommunication was the worst sociopolitical fate for any leader, far worse than merely being labeled a “traitor” (which they called di Rienzi as well).

A whole list of crimes were put forth against the Tribune (including, absurdly, necromancy), and the Pope began to actively collaborate with the barons for the “final act” against the Rienzian regime. By this time, di Rienzi and the Roman people had decisively defeated the barons in the battle of Porta San Lorenzo. But it did not matter. In the year 1347, the Church, and the spiritual power of the Pope, was far more powerful than any army, any military victory. So, with the aid of the Pope, the barons rebelled and deposed di Rienzi, who was forced into exile.

Even then the Pope was not satisfied, remaining “fixated” on di Rienzi, scheming to have him captured and “annihilated.” Such was the hatred of this “Christian man of God” for the Tribune who wished to create regeneration for Romans and Italians. Could di Rienzi, in the fourteenth century, have said “Basta!” and defied the Church? Consider that Mussolini in the twentieth century could not do so, to his detriment. The secular power and ambitions of the Church was and remains a shackle on the aspirations of the Italian people.

Cola di Rienzi attempted to find sanctuary in Prague with the emperor Charles IV who eventually bowed to the overwhelming power of the papacy and turned di Rienzi over to the Inquisition for trial for “heresy.” Part of di Rienzi’s defense was his assertion — somewhat “outrageous” for the fourteenth century — that the church should have no secular power, since the founding basis for Christianity was “poverty and humility.” One can only imagine Pope Clements’s reaction to that.

Eventually brought before Pope Clement, di Rienzi was a shell of his former self, and the symbolism of this meeting cannot be dismissed. The populist and secular (yet devoutly religious) hope of Italy was brought as a humiliated prisoner before the man representing the memetic virus that has infected the West and enslaved the Italian people for centuries.

The worm turned after the death of Clement VI and the ascension of Pope Innocent VI, a less “worldly and extravagant” man than his predecessor. Innocent had, not surprisingly, secular aspirations in Rome and was therefore distressed by the violence and anarchy prevailing after the fall of di Rienzi and the rise, once again, of the baronial families. Therefore, Cola was “rehabilitated” and sent to Rome as a Papal puppet to restore his “good state” — but this time, as Innocent writes, without the “fantastic innovations” of the first Rienzian regime.

Of course, those “fantastic innovations” were merely the assertion of the Roman peoples’ right to rule themselves in a secular state independent of papal micromanagement, and that Rome and Italy were in dire need of regeneration and renewal. This was not exactly what the church wanted, or wants today. And so, a chastened Cola di Rienzi was put forward as Pope Innocent’s tool with the hope that the repeat of the Rienzian regime would not degenerate into farce. Rome not being what she once was, that hope was misplaced.

The ex-tribune (now “senator” and Papal rector) was painfully aware that the real leader of Rome was the Pope, not the Emperor, not any self-proclaimed Tribune. This is something that he had dedicated years to opposing. From the beginning of his second tenure of power — power only at the sufferance of the Pope — the established elites, particularly the barons, opposed and plotted against di Rienzi. The plots became complicated and di Rienzi, after years of imprisonment and hardship, and possibly suffering from epilepsy, was not the same man. Errors of judgment, executions of venerable Roman citizens, and the imposition of required taxes began to fray the support of the fickle Roman masses.

When the end came, at the instigation of the barons and their supporters, it came fast. The howling mob stormed di Rienzi’s residence and drowned out his attempts to reason with them. Cola di Rienzi was caught trying to flee the mob in disguise (like Mussolini); he was stabbed to death (like Caesar); his body was desecrated (like Mussolini again) then burnt to ashes (like Hitler). The ashes were thrown into the Tiber; all physical traces of the Tribune were gone.

The eerily similar lives and political careers of di Rienzi and Mussolini should give one pause. Both men were Italians living in a time of crisis for their people. Both men rose up to lead populist revolts against the established order. Both men established regimes which were initially successful and lauded by many, but then these regimes went sour and were overthrown by the forces of reaction. Both men were imprisoned thereafter. Both men then returned to power through the help of another, more powerful person — in the case of di Rienzi it was the Pope, in the case of Mussolini, Hitler. Both men then attempted to reestablish their regime, eventually failed, were killed by their enemies, and their bodies were desecrated by the mob. Both men attempted to lift the Italian people to greatness, but the special interests were too powerful and the lure of insipid, hedonistic stagnation too great.

The similarities are too many to be a coincidence. This then seems to be a distinctly Italian phenomenon. Who was at fault? Was it the fault of the two leaders themselves? Were they fatally flawed men? No doubt both men, particularly di Rienzi, had their flaws, and these flaws contributed to their failure and demise. But all great men have flaws. This easy explanation does not suffice.

No, the Italian people also have to share the blame, and I say this as a pan-European racial nationalist who is very supportive of the Italian people. Nevertheless, twice in Italy’s modern history dynamic leaders came to the fore to lead Italians to greatness, and twice did the Italian people turn on them. (In defense of the Italians, one has to ask if any other European societies have done better. One might say that it is better to have tried and failed a Rienzi or a Mussolini than never to have tried at all, which is the case of most European societies.)

I cannot forget reading Leon DeGrelle’s book on his experiences on the eastern front (translated as Campaign in Russia), fighting for Europe as part of the Wallonian division of the Waffen SS. The Italian soldiers he met were uninterested in fighting. They had no sense of the seriousness of the crusade against Bolshevism and for Europe. Instead, they cared only about “wine, women, and fun in the sun.” Nietzsche’s “last men” to be sure! (The rest of Europe has surely caught up with the Italians since then.) No wonder Italian military performance in WW II was a farce. No wonder that Italians have so long been the anvil of history, not the hammer, a fact lamented by great Italians from the middle ages to Machiavelli to Julius Evola to the present day.

But we cannot solely blame the Italians or focus on the personal flaws of di Rienzi and Mussolini. No, the 800 pound gorilla in the room is the Vatican.

An analysis of the career of di Rienzi clearly shows the pernicious influence of Pope Clement VI. Musto’s book makes it clear that Clement VI was little more than a self-interested feudal lord, more concerned with maintaining petty Papal power and privilege than in the national regeneration promised by di Rienzi. For example, on page 190 we read of the Pope’s real attitude toward di Rienzi’s new regime: “. . . the pope began carefully, delicately plotting Cola’s downfall and seeking his personal humiliation, as well as his public infamita as a traitor and a heretic.” In short, the church plotted to crush the political aspirations of the Italian people to keep them in secular servitude to the Vatican.

There is a long history of such behavior. Cola di Rienzi was not the first man to attempt Italian/Roman regeneration only to fall victim to the Vatican. As Musto tells us, in 1143, the people of Rome rose up against Pope Innocent II, drove the papacy into exile, re-established the Roman Senate, and even started minting coins in the name of “SPQR” — “The Senate and the People of Rome.” Arnold of Brescia, a monk and political philosopher, rose to lead the new republic and offered an intellectual rationale for the church’s renunciation of secular power. But in 1155, at the instigation of the papacy, the German Emperor Frederick I led an army against Rome to crush the republic and reinstall the pope. Arnold of Brescia was burned at the stake as a heretic and his ashes dumped into the Tiber. Yes, to preserve its power, the church turned to foreigners to suppress the political aspirations of the Romans.

The secular power of the church caused a “dual loyalty” problem that remains to this day. Is an Italian’s highest loyalty to Italy or to the Vatican? To di Rienzi and Mussolini or to the Pope? (Or, in Il Duce’s Italy, to the Pope as well as the secular figurehead, the King?) It is interested to contemplate how history might have been changed if the papacy had remained in Avignon, if the church had been disestablished and the papacy denied sovereign status once and for all after the reunification of Italy, or if Mussolini had not signed the Lateran Treaty of 1929, rescuing papal sovereignty from the legal limbo in which it had languished since 1861.

The other major party opposed to Cola di Rienzi were the barons of medieval Rome. As a self-interested elite, enriching themselves at the cost of the people’s well being, they are perfectly analogous to the white globalist elites of today, who routinely betray their race’s interests in their hedonistic pursuit of money, power, and pleasure.

The barons of di Rienzi’s time are also analogous to the established elites (King, nobility, military, and business) of Mussolini’s Italy. These elites opposed a full and radical fascistization of the Italian people and instead valued the well-being of their own caste over that of society as a whole. European-derived peoples, with their greater individualism, tend to produce elites willing to betray their race (and their own ethnic genetic interests) for selfish class/caste/individual interests.

What are the lessons of the story of Cola di Rienzi?

Culturally and politically, the Italians are one of the healthiest people in Europe today. Their tradition of palingenetic populist nationalism has deep roots, nourished and hallowed by the blood of martyrs like Arnold of Brescia, Cola di Rienzi, and Benito Mussolini. They failed because they could not overcome the resistance of the “barons” and the church — those whose petty secular interests are threatened by genuine national renewal. The next time — if there is a next time — things need to be done right.

For the West as a whole, the story of di Rienzi demonstrates that self-interested established elites always oppose palingenesis. It is time for a new elite, one that understands that their own interests and those of their people are one and the same, and who will work first towards survival, and second towards fulfilling a higher destiny, the Destiny of the West.

Will “the people” be up to the challenge? We shall see. One thing is for sure — we cannot afford to waste the likes of a di Rienzi or a Mussolini. Such leaders need to be treasured, not to have their torn bodies hanged upside down for the amusement of the small-brained, milling mob.

It is time for a clean sweep. Reform is the enemy. Only complete rebirth can save us now.

Even his own name has been turned against him. Indeed it is hardly flattering to be described as “Machiavellian.” One immediately envisions a hint of cunning and treacherous violence. And yet what led Machiavelli to write his most famous and scandalous works, The Prince

Even his own name has been turned against him. Indeed it is hardly flattering to be described as “Machiavellian.” One immediately envisions a hint of cunning and treacherous violence. And yet what led Machiavelli to write his most famous and scandalous works, The Prince, was concern for his fatherland, Italy.In his time, in the first years of the 16th century, he was, moreover, the only one who cared about this geographical entity. Then, one thought about Naples, Genoa, Rome, Florence, Milan, or Venice, but nobody thought of Italy. For that, it was necessary to wait three more centuries. Which proves that one should never despair. The prophets always preach in spiritual wastelands before their dreams rouse the unpredictable interest of the people.

, drawing on the lessons of ancient history, he wonders about the religion that would be best suited for the health of the State: “Our religion placed the supreme good in humility and contempt for human things. The other [the Roman religion] placed it in the nobility of soul, the strength of the body, and all other things apt to make men strong. If our religion requires that one have strength, it is to be more suited for suffering than for strong deeds. This way of life thus seems to have weakened the world and to have made it prey for scoundrels” (Discourses, Book II, ch. 2). Machiavelli never hazarded religious reflections, but only political reflections on religion, concluding, however: “I prefer my fatherland to my own soul.”

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

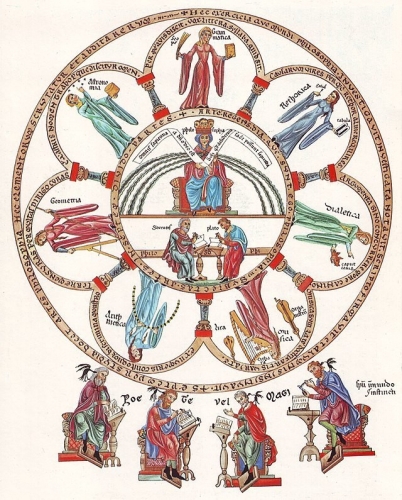

Another problem with a modern human is poor memory. Why remember something if you can find all the information on the Internet? Xenophon reports that Athenian politician and general Nicias forced his son Niceratus to memorize by heart the works of Homer. Now no one even tries to set such a task for themselves. It has reached the point that today not everyone is also able to finish reading the epic of Homer to the end. Alberto Manguel writes in “Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey: A Biography” that memory training in the Byzantine educational system was given considerable attention: after several years of practice, students had to know the Iliad by heart.

Another problem with a modern human is poor memory. Why remember something if you can find all the information on the Internet? Xenophon reports that Athenian politician and general Nicias forced his son Niceratus to memorize by heart the works of Homer. Now no one even tries to set such a task for themselves. It has reached the point that today not everyone is also able to finish reading the epic of Homer to the end. Alberto Manguel writes in “Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey: A Biography” that memory training in the Byzantine educational system was given considerable attention: after several years of practice, students had to know the Iliad by heart. Joel Barker, in his book “Paradigms: Business of Discovering the Future”, emphasizes that he does not agree with Thomas Kuhn, who believed that paradigms exist only in science. I always emphasize that I use the word “paradigm” without any reference to Kuhn’s paradigm theory, and take its original meaning (from Greek. παράδειγμα, “example, model, sample”). So, Barker is convinced that the new paradigm comes sooner than there is a need for it. The paradigm is always ahead of demand. And, of course, the apparent reaction to this is rejection. Who is changing the paradigm, according to Barker? It’s always an outsider. The one who breaks the rules turns them — at the same time improving the world. “What is defined as impossible today is impossible only in the context of present paradigms,” says Barker. Let’s put the question again: “is it Possible to become Renaissance human in the digital age? This is not possible only in the context of the old paradigm. But that paradigm could disappear by tomorrow.

Joel Barker, in his book “Paradigms: Business of Discovering the Future”, emphasizes that he does not agree with Thomas Kuhn, who believed that paradigms exist only in science. I always emphasize that I use the word “paradigm” without any reference to Kuhn’s paradigm theory, and take its original meaning (from Greek. παράδειγμα, “example, model, sample”). So, Barker is convinced that the new paradigm comes sooner than there is a need for it. The paradigm is always ahead of demand. And, of course, the apparent reaction to this is rejection. Who is changing the paradigm, according to Barker? It’s always an outsider. The one who breaks the rules turns them — at the same time improving the world. “What is defined as impossible today is impossible only in the context of present paradigms,” says Barker. Let’s put the question again: “is it Possible to become Renaissance human in the digital age? This is not possible only in the context of the old paradigm. But that paradigm could disappear by tomorrow.

Tobias Rees is the founding Director of the Institute’s Transformations of the Human Program.

Tobias Rees is the founding Director of the Institute’s Transformations of the Human Program.

A young Italian nationalist leads his followers on a march through Rome, seizing power from corrupt elites to establish a palingenetic regime. Declaring himself Tribune, his ultimate aim is to recreate the power and glory of Ancient Rome. However, a conspiracy of his enemies topples him from power, and he is imprisoned. Eventually, the most powerful man in the West frees him and restores him to power — albeit as leader of a puppet regime. His second attempt at Italian rebirth is cut short; he is captured, killed, and his body desecrated by the howling mob. A man who had attempted to drive his degenerate countrymen to fulfill a higher destiny is cut down by the unthinking masses — a cowardly herd who lacked the ability to comprehend, much less work towards, this leader’s dreams of glory.

A young Italian nationalist leads his followers on a march through Rome, seizing power from corrupt elites to establish a palingenetic regime. Declaring himself Tribune, his ultimate aim is to recreate the power and glory of Ancient Rome. However, a conspiracy of his enemies topples him from power, and he is imprisoned. Eventually, the most powerful man in the West frees him and restores him to power — albeit as leader of a puppet regime. His second attempt at Italian rebirth is cut short; he is captured, killed, and his body desecrated by the howling mob. A man who had attempted to drive his degenerate countrymen to fulfill a higher destiny is cut down by the unthinking masses — a cowardly herd who lacked the ability to comprehend, much less work towards, this leader’s dreams of glory.