Apollo’s name has no clear parallels in other Indo-European languages, and he is the only Olympian god whose name does not figure on the Linear B tablets (a word fragment on a Cnossus tablet has been read as a form of his name, but the reading is highly conjectural and has convinced few scholars). The absence may well be significant. We possess well over a thousand texts that come from the palaces of Thebes in Boeotia, Mycenae, and Pylus in the Peloponnese, Cnossus and Chania on Crete, that is from practically the entire geographical area of the Mycenaean world, with the exception of the west coast of Asia Minor. Only a fraction contains information on religion, not only the names of gods and their sanctuaries, but also month names that preserve a major festival and personal names that contain a divine name (so-called theophoric names); but the sample is large enough to preserve almost all major Greek divine names. Thus, there is enough material to make an omission seem statistically significant and not just the result of the small size of the sample. But the absence creates a problem: if Apollo did not exist in Bronze Age Greece, where did he come from?

Scholars have attempted several answers. None has remained uncontested. There are four main possibilities: Apollo could be an Indo-European divinity, present although not attested in Bronze Age Greece, or introduced from the margins of the Mycenaean world after its collapse; or he was not Greek but Near Eastern, with again the options of a hidden presence in Bronze Age Greece or a later introduction. Scholars who accepted the absence of Apollo from the Mycenaean pantheon had two options. If he had no place in Mycenaean Greece, he had to come from elsewhere, at some time between the fall of this world and the epoch of Homer and Hesiod, that is during the so-called “Dark Age” and the following Geometric Epoch. During most of this period, Greece had isolated itself from Near Eastern influences but was internally changed by population movements, especially the expansion of the Dorians from the mountains of Northwestern Greece, outside the Mycenaean area, into what had constituted the core of the Mycenaean realm, the Peloponnese, Crete, and the Southern Aegean. Thus, a Dorian origin of Apollo was an almost obvious hypothesis; but since the Dorians were Greeks, albeit with a different dialect, one had to come up with a Greek or at least an Indo-European etymology for his name to make this convincing. If, however, scholars could find no such etymology, they assumed an Anatolian or West Semitic origin: in Western Anatolia, Greeks had already settled during Mycenaean times but arrived again in large numbers during the Dark Age, and contacts with Phoenicia became frequent well before Homer, as the arrival of the alphabet around 800 BCE shows. Finally, if one did not accept Apollo’s absence in the Linear B texts as proof of his historical absence in the Mycenaean world (after all, the argument was based on statistics only), or if one accepted the one fragment from Cnossus, there was even more occasion for Anatolian or Near Eastern origins, in the absence of an Indo-European etymology.

A Bronze Age Apollo of whatever origin could find corroboration in Apollo’s surprising and early presence on the island of Cyprus. Excavations have found several archaic sanctuaries, some being simple open-air spaces with an altar, others as complex as the sanctuary of Apollo Hylatas at Kourion that may have contained a rectangular temple as early as the sixth or even late seventh century BCE. Inscriptions in the local Cypriot writing system attest several cults of Apollo with varying epithets, from Amyklaios to Tamasios, and a month whose name derives from Apollo Agyieus.

In a way, Apollo should not exist on Cyprus, or only in later times, if he was Dorian or entered the Greek world after the collapse of the Bronze Age societies. Cyprus, the large island that bridged the sea between Southern Anatolia and Western Syria, was inhabited by a native population; Greeks arrived at the very end of the Mycenaean period. They must have been Mycenaean Greeks who were displaced by the turmoil at the time when their Greek empire was crumbling. They brought with them their language, a dialect that was akin to the dialect of Arcadia in the Central Peloponnese to where Mycenaeans retreated from the invading Dorians, and they brought with them their writing system, a syllabic system closely connected with Linear A and B that quickly developed its own local variation and survived until Hellenistic times; then it was ousted by the more convenient Greek alphabet. The long survival of this system shows that, after its importation in the eleventh century BCE, Cypriot culture was very stable and only slowly became part of the larger Greek world. There was no later Greek immigration, either large-scale or modest, during the Iron Age: when Phoenicians immigrated in the eighth century, Cypriot culture, if anything, turned to the Near East. It is only plausible to assume that the Mycenaean settlers also brought their cults and gods with them: thus, the gods and festivals attested in the Cypriot texts are likely to reflect not Iron Age Greek religion but the Mycenaean heritage imported at the very end of the Bronze Age.

In a way, Apollo should not exist on Cyprus, or only in later times, if he was Dorian or entered the Greek world after the collapse of the Bronze Age societies. Cyprus, the large island that bridged the sea between Southern Anatolia and Western Syria, was inhabited by a native population; Greeks arrived at the very end of the Mycenaean period. They must have been Mycenaean Greeks who were displaced by the turmoil at the time when their Greek empire was crumbling. They brought with them their language, a dialect that was akin to the dialect of Arcadia in the Central Peloponnese to where Mycenaeans retreated from the invading Dorians, and they brought with them their writing system, a syllabic system closely connected with Linear A and B that quickly developed its own local variation and survived until Hellenistic times; then it was ousted by the more convenient Greek alphabet. The long survival of this system shows that, after its importation in the eleventh century BCE, Cypriot culture was very stable and only slowly became part of the larger Greek world. There was no later Greek immigration, either large-scale or modest, during the Iron Age: when Phoenicians immigrated in the eighth century, Cypriot culture, if anything, turned to the Near East. It is only plausible to assume that the Mycenaean settlers also brought their cults and gods with them: thus, the gods and festivals attested in the Cypriot texts are likely to reflect not Iron Age Greek religion but the Mycenaean heritage imported at the very end of the Bronze Age.This leaves room for many theories and ideas that followed the pattern I outlined above. Only two attempts have commanded more than passing attention, a derivation from the Hittite pantheon in Bronze Age Anatolia and a Dorian hypothesis that made Apollo the main divinity of the Dorians who pushed south from their original home in Northwestern Greece, once the fall of the Mycenaean Empire let them do so.

Problems remain, besides Apollo’s absence from Linear B and the thorny question of how the Iliad relates to Bronze Age history, even after the rejection of Hrozný’s reading. Contemporary proponents of an Anatolian Apollo still follow Hrozný and point to Apollo’s Lycian connection that is already present in Homer; they feel encouraged by Wilamowitz, the most influential classicist in Hrozný’s time, who had concurred. But Lycian inscriptions found since then in Xanthus, where Leto had her main shrine, have cast severe doubts on whether Wilamowitz was right. Neither Leto’s nor Apollo’s name is attested in the indigenous texts, among which pride of place belongs to a text dated to 358 BCE, written in Lycian, Greek, and Aramaic. As in a few other indigenous texts, Leto is “The Mother of the Sanctuary” (meaning the one in Xanthus), without a proper name. Only in the Aramaic text has what one would call the Apolline triad, Lato (l’tw’), Artemus (’rtemwš) and a god called Hšatrapati, the Iranian Mitra Varuna as the equivalent of the young powerful god whom Greeks called Apollo. In the Lycian text, the Greek personal name Apollodotus, “given by Apollo” was rendered in Lycian in way that made clear that the Lycian equivalent of Apollo was Natr-, a name of uncertain etymology but one that has no linguistic relation whatsoever with Apollo. No member of the Apolline triad, then, had a Lycian name that sounded like Leto, Apollo, or Artemis: the names were Greek, not indigenous to Lycia. Lycia may have been Apollo’s country in myth (and in Homer), but not in history. The sanctuary of Xanthus does not transform Hittite cults into the Iron Age, and a Bronze Age Anatolian Apollo seems far-fetched, to say the least. This directs our quest back to Greece.

In this reading, Apollo arrived in Greece with the Dorians who slowly moved into the Peloponnese and from there took over the towns of Crete, after the fall of Mycenaean power. Four centuries later, at the time of Homer and Hesiod, the god had become an established divinity in all of Greece, and a firm part of the narrative tradition of epic poetry. Such an expansion presupposes some degree of religious and cultural interpenetration and exchange throughout Greece during the Dark Ages. This somewhat contradicts the traditional image of this period as a time when the single communities of Greece were mostly turned towards themselves, with little connection with each other. But such a picture is based mainly on the rather scarce archaeological evidence; communication between people, even migration, does not always leave archaeological traces, and cults are based on myths and narratives, not on artifacts. And well before Homer, communications inside Greece opened up again, as shown by the rapid spread of the alphabet or of the so-called Proto-Geometric pottery style that both belong to the ninth or early eighth centuries BCE.

In this reading, Apollo arrived in Greece with the Dorians who slowly moved into the Peloponnese and from there took over the towns of Crete, after the fall of Mycenaean power. Four centuries later, at the time of Homer and Hesiod, the god had become an established divinity in all of Greece, and a firm part of the narrative tradition of epic poetry. Such an expansion presupposes some degree of religious and cultural interpenetration and exchange throughout Greece during the Dark Ages. This somewhat contradicts the traditional image of this period as a time when the single communities of Greece were mostly turned towards themselves, with little connection with each other. But such a picture is based mainly on the rather scarce archaeological evidence; communication between people, even migration, does not always leave archaeological traces, and cults are based on myths and narratives, not on artifacts. And well before Homer, communications inside Greece opened up again, as shown by the rapid spread of the alphabet or of the so-called Proto-Geometric pottery style that both belong to the ninth or early eighth centuries BCE.The main obstacle to this hypothesis is Apollo’s well-attested presence on Cyprus, in a form, Apeilon, that is very close to the Dorian Apellon: would not Apollo then be a Cypriot? Burkert removed this obstacle with the assumption of a very early import to Cyprus from Dorian Amyclae; Amyclae, we remember, had an important and old shrine of the god. Another scenario is possible as well: the Mycenaean lords who fled to Cyprus did so only after their society integrated a part of the Dorian intruders and their tutelary god Apollo. After all, the pressure of the Dorians must have been felt for quite a while, and their bands that were organized around the cult of Apollo could have started to trickle south even before the fall of the kingdoms, and blended in with the Mycenaeans.

Overall, then, I am still inclined to follow Burkert’s hypothesis that is grounded in social and political history, rather than to accept somewhat vague Anatolian origins – even if I am aware that the neat coincidence of etymology and function might well be yet another of these circular mirages of which the history of etymologizing divine names is so full. And it needs to be stressed that the picture of a simple diffusion from the invading Dorians to the rest of Greece is somewhat too neat. Things, as often, are messier, for two reasons: there are clear traces of Near Eastern influence in Apollo’s myth and cult, and there are vestiges of a Mycenaean tradition that cannot be overlooked.

In the past, arguments from the calendar were paramount. In the calendar of the Greeks, a month coincides with one cycle of the moon: the first day thus is the day when the moon will just be visible, the seventh day is the day when the moon is half full and as such clearly visible. Apollo is connected with both days. The seventh day is somewhat more prominent: every month, Apollo receives a sacrifice on the seventh day, all his major festivals are held on a seventh, and his birthday is on the seventh day of a specific month. But already in Homer, he is also connected with new moon, noumēnía: he is Noumenios, and his worshippers can be organized in a group of noumeniastai. Long ago, Martin P. Nilsson, the leading scholar on Greek religion in the first half of the last century, connected this with the Babylonian calendar where the seventh day is very important. He went even further. Every lunar calendar will, rather fast, get out of step with the solar cycle that defines the seasonal year; to remedy this, all systems invented intercalation, the insertion of additional days. Greek calendars introduced an extra month every ninth year, to cover the gap between the solar and the lunar cycle. According to Nilsson, they did so under Babylonian influence that was mediated through Delphi: Delphi’s main festivals were originally held every ninth year, and only Delphi would have enough influence in the Archaic Epoch to impose such a system upon all Greek states. However, this is very speculative; Nilsson certainly was wrong in his additional assumption that Delphi also introduced the system of months: month names are already attested in the Greek Bronze Age. Still, the connection of Apollo’s seventh day with the prominence of the same day in the Mesopotamian calendar is interesting.

As to healing, it seems by now established that itinerant Near Eastern healers visited Greece during the Archaic Age and left their traces. The most tangible trace is the role the dog plays in the cult of Asclepius: the dog is central to the Mesopotamian goddess of healing, Gula, two of whose statuettes were dedicated in seventh-century Samos. In Akkadian, Gula is also called azugullatu, “Great Physician”: the word may be at the root of Asclepius’ name, and it resonates in a singular cult title of Apollo on the island of Anaphe, Asgelatas. Later, Greeks turned the epithet into Aiglatas, from aigle “radiance,” and told the story that Apollo appeared to the Argonauts as a radiant star to save them from shipwreck. This looks like the later rationalization of a word that nobody understood anymore and that may be a trace of an Oriental healer who instituted this specific cult. Another Oriental detail is the plague arrows Apollo shoots in Iliad 1, as we saw, and his role as an armed gatekeeper to keep away pestilence that is attested in several Clarian oracles.

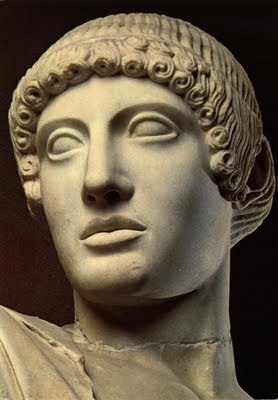

In narratives from Ugarit in Northern Syria, the Storm God is accompanied by Reshep, the plague god or “Lord of the Arrow.” In bilingual inscriptions from Cyprus, his Phoenician equivalent, also called Reshep, becomes Greek Apollo. In iconography, Reshep is usually represented as a warrior with a helmet and a very short tunic, walking and brandishing a weapon with his raised right arm; these images are attested in the Eastern Mediterranean from the late Bronze Age to the Greek Archaic Age. In Cyprus, such a god appears in a famous bronze image from the large sanctuary complex at Citium; since he wears a helmet adorned with two horns, some scholars understood him as the Bronze Age version of the later Cypriot Apollo Keraïtas, “Horned Apollo.”

Greek Apollo, most of the time, looks very different. But a very similar statuette has been found in Apollo’s sanctuary at Amyclae in Southern Sparta. Here, it must reflect Apollo’s archaic statue in this sanctuary that we know from Pausanias’ description:

"I know nobody who might have measured its size, but I guess it must be about thirty cubits high. It is not the work of Bathycles [the sculptor who made the base for the image], but old and not worked with artifice. It has no face, and its hands and feet are added from stone, the rest looks like a bronze column. On its head, it has a helmet, in its hands a lance and a bow."

(Description of Greece, 3.10.2)

An image on a coin shows not only that the body could be dressed in a cloak to soften the strangeness of its shape but also that it brandished the lance with its raised right hand: the coincidence with the Reshep iconography seems perfect, and the Oriental influence almost obvious. It has even been suggested that the place name Amyclae is Near Eastern: there is a Phoenician Reshep Mukal, “Mighty Reshep,” whom the Cypriot Greeks translated as Apollo Amyklos. The Greek epithet cannot derive from the place name (it would have to be Amyklaîos), but it shares the same verbal root; its basic phonetic structure is the same as that of mukal. Thus, one wonders whether it was Phoenician or Cypriot sailors who first founded a sanctuary on this lonely promontory on one of the trade routes to the west.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

The Apollonian and the Dionysian are two cognitive states in which art appears as the power of nature in man.[6] Art for Nietzsche is fundamentally not an expression of culture, but is what Heidegger calls “eine Gestaltung des Willens zur Macht” a manifestation of the will to power. And since the will to power is the essence of being itself, art becomes “die Gestaltung des Seienden in Ganzen,” a manifestation of being as a whole.[7] This concept of the artist as a creator, and of the aspect of the creative process as the manifestation of the will, is a key component of much of Nietzsche’s thought – it is the artist, the creator who diligently scribes the new value tables. Taking this into accord, we must also allow for the possibility that Thus Spake Zarathustra opens the doors for a new form of artist, who rather than working with paint or clay, instead provides the Uebermensch, the artist that etches their social vision on the canvas of humanity itself. It is in the character of the Uebermensch that we see the unification of the Dionysian (instinct) and Apollonian (intellect) as the manifestation of the will to power, to which Nietzsche also attributes the following tautological value “The Will to Truth is the Will to Power”.[8] This statement can be interpreted as meaning that by attributing the will to instinct, truth exists as a naturally occurring phenomena – it exists independently of the intellect, which permits many different interpretations of the truth in its primordial state. The truth lies primarily in the will, the subconscious, and the original raw instinctual state that Nietzsche identified with Dionysus. In The Gay Science Nietzsche says:

The Apollonian and the Dionysian are two cognitive states in which art appears as the power of nature in man.[6] Art for Nietzsche is fundamentally not an expression of culture, but is what Heidegger calls “eine Gestaltung des Willens zur Macht” a manifestation of the will to power. And since the will to power is the essence of being itself, art becomes “die Gestaltung des Seienden in Ganzen,” a manifestation of being as a whole.[7] This concept of the artist as a creator, and of the aspect of the creative process as the manifestation of the will, is a key component of much of Nietzsche’s thought – it is the artist, the creator who diligently scribes the new value tables. Taking this into accord, we must also allow for the possibility that Thus Spake Zarathustra opens the doors for a new form of artist, who rather than working with paint or clay, instead provides the Uebermensch, the artist that etches their social vision on the canvas of humanity itself. It is in the character of the Uebermensch that we see the unification of the Dionysian (instinct) and Apollonian (intellect) as the manifestation of the will to power, to which Nietzsche also attributes the following tautological value “The Will to Truth is the Will to Power”.[8] This statement can be interpreted as meaning that by attributing the will to instinct, truth exists as a naturally occurring phenomena – it exists independently of the intellect, which permits many different interpretations of the truth in its primordial state. The truth lies primarily in the will, the subconscious, and the original raw instinctual state that Nietzsche identified with Dionysus. In The Gay Science Nietzsche says:

Myths of Dionysus are often used to depict a stranger or an outsider to the community as a repository for the mysterious and prohibited features of another culture. Unsavory characteristics that the Greeks tend to ascribe to foreigners are attributed to him, and various myths depict his initial rejection by the authority of the polis – yet Dionysus’ birth at Thebes, as well as the appearance of his name on Linear B tablets, indicates that this is no stranger, but in fact a native, and that the rejected foreign characteristics ascribed to him are in fact Greek characteristics.[13] Rather than being a representative of foreign culture what we are in fact observing in the character of Dionysus is the archetype of the outsider; someone who sits outside the boundaries of the cultural norm, or who represents the disruptive element in society which either by its nature effects a change or is removed by the culture which its very presence threatens to alter. Dionysus represents as Plutarch observed, “the whole wet element” in nature – blood, semen, sap, wine, and all the life giving juice. He is in fact a synthesis of both chaos and form, of orgiastic impulses and visionary states – at one with the life of nature and its eternal cycle of birth and death, of destruction and creation.[14] This disruptive element, by being associated with the blood, semen, sap, and wine is an obvious metaphor for the vital force itself, the wet element, being representative of “life in the raw”. This notion of “life” is intricately interwoven into the figure of Dionysus in the esoteric understanding of his cult, and indeed throughout the philosophy of the Greeks themselves, who had two different words for life, both possessing the same root as Vita (Latin: Life) but present in very different phonetic forms: bios and zoë.[15]

Myths of Dionysus are often used to depict a stranger or an outsider to the community as a repository for the mysterious and prohibited features of another culture. Unsavory characteristics that the Greeks tend to ascribe to foreigners are attributed to him, and various myths depict his initial rejection by the authority of the polis – yet Dionysus’ birth at Thebes, as well as the appearance of his name on Linear B tablets, indicates that this is no stranger, but in fact a native, and that the rejected foreign characteristics ascribed to him are in fact Greek characteristics.[13] Rather than being a representative of foreign culture what we are in fact observing in the character of Dionysus is the archetype of the outsider; someone who sits outside the boundaries of the cultural norm, or who represents the disruptive element in society which either by its nature effects a change or is removed by the culture which its very presence threatens to alter. Dionysus represents as Plutarch observed, “the whole wet element” in nature – blood, semen, sap, wine, and all the life giving juice. He is in fact a synthesis of both chaos and form, of orgiastic impulses and visionary states – at one with the life of nature and its eternal cycle of birth and death, of destruction and creation.[14] This disruptive element, by being associated with the blood, semen, sap, and wine is an obvious metaphor for the vital force itself, the wet element, being representative of “life in the raw”. This notion of “life” is intricately interwoven into the figure of Dionysus in the esoteric understanding of his cult, and indeed throughout the philosophy of the Greeks themselves, who had two different words for life, both possessing the same root as Vita (Latin: Life) but present in very different phonetic forms: bios and zoë.[15]