The news that Lyudmila Alekseyeva, head of the Russian Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) the Moscow-Helsinki Group, will be returning to the Presidential Council for Human Rights, has been heralded by many in the liberal establishment in Russia as a victory for their cause. Indeed, as an adversary of President Putin on numerous occasions, Alekseyeva has been held as a symbol of the pro-Western, pro-US orientation of Russian liberals who see in Russia not a power seeking independence and sovereignty from the global hegemon in Washington, but rather a repressive and reactionary country bent on aggression and imperial revanchism.

While this view is not one shared by the vast majority of Russians – Putin’s approval rating continues to hover somewhere in the mid 80s – it is most certainly in line with the political and foreign policy establishment of the US, and the West generally. And this is precisely the reason that Alekseyeva and her fellow liberal colleagues are so close to key figures in Washington whose overriding goal is the return of Western hegemony in Russia, and throughout the Eurasian space broadly. For them, the return of Alekseyeva is the return of a champion of Western interests into the halls of power in Moscow.

Washington and Moscow: Competing Agendas, Divergent Interests

Perhaps one should not overstate the significance of Alekseyeva as an individual. This Russian ‘babushka’ approaching 90 years old is certainly still relevant, though clearly not as active as she once was. Nevertheless, one cannot help but admire her spirit and desire to engage in political issues at the highest levels. However, taking the pragmatic perspective, Alekseyeva is likely more a figurehead, a symbol for the pro-Western liberal class, rather than truly a militant leader of it. Instead, she represents the matriarchal public face of a cohesive, well-constructed, though relatively marginal, liberal intelligentsia in Russia that is both anti-Putin, and pro-Western.

There could be no better illustration of this point than Alekseyeva’s recent meeting with US Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland while Ms. Nuland was in Moscow for talks with her Russian counterparts. Alekseyeva noted that much of the meeting was focused on anti-US perception and public relations in Russia, as well as the reining in of foreign-sponsored NGOs, explaining that, “[US officials] are also very concerned about the anti-American propaganda. I said we are very concerned about the law on foreign agents, which sharply reduced the effectiveness of the human rights community.”

There are two distinctly different, yet intimately linked issues being addressed here. On the one hand is the fact that Russia has taken a decidedly more aggressive stance to US-NATO machinations throughout its traditional sphere of influence, which has led to demonization of Russia in the West, and the entirely predictable backlash against that in Russia. According to the Levada Center, nearly 60 percent of Russians believe that Russia has reasons to fear the US, with nearly 50 percent saying that the US represents an obstacle to Russia’s development. While US officials and corporate media mouthpieces like to chalk this up to “Russian propaganda,” the reality is that these public opinion numbers reflect Washington and NATO’s actions, not their image, especially since the US-backed coup in Ukraine; Victoria Nuland herself having played the pivotal role in instigating the coup and setting the stage for the current conflict.

So while Nuland meets with Alekseyeva and talks of the anti-US perception, most Russians correctly see Nuland and her clique as anti-Russian. In this way, Alekseyeva, fairly or unfairly, represents a decidedly anti-Russian position in the eyes of her countrymen, cozying up to Russia’s enemies while acting as a bulwark against Putin and the government.

And then of course there is the question of the foreign agents law. The law, enacted in 2012, is designed to make transparent the financial backing of NGOs and other organizations operating in Russia with the financial assistance of foreign states. While critics accuse Moscow of using the law for political persecution, the undeniable fact is that Washington has for years used such organizations as part of its soft power apparatus to be able to project power and exert influence without ever having to be directly involved in the internal affairs of the targeted country.

From the perspective of Alekseyeva, the law is unjust and unfairly targets her organization, the Moscow-Helsinki Group, and many others. Alekseyeva noted that, “We are very concerned about the law on foreign agents, which sharply reduced the effectiveness of the human rights community… [and] the fact the authorities in some localities are trying more than enough on some human rights organizations and declare as foreign agents those who have not received any foreign money or engaged in politics.”

While any abuse of the law should rightly be investigated, there is a critical point that Alekseyeva conveniently leaves out of the narrative: the Moscow-Helsinki Group (MHG) and myriad other so-called “human rights” organizations are directly supported by the US State Department through its National Endowment for Democracy, among other sources. As the NED’s own website noted, the NED provided significant financial grants “To support [MHG’s] networking and public outreach programs. Endowment funds will be used primarily to pay for MHG staff salaries and rental of a building in downtown Moscow. Part of the office space rented will be made available at a reduced rate to NGOs that are closely affiliated with MHG, including other Endowment grantees.” The salient point here is that the salary of MHG staff, the rent for their office space, and other critical operating expenses are directly funded by the US Government. For this reason, one cannot doubt that the term “foreign agent” directly and unequivocally applies to Alekseyeva’s organization.

But of course, the Moscow-Helsinki Group is not alone as more than fifty organizations have now registered as foreign agents, each of which having received significant amounts from the US or other foreign sources. So, an objective analysis would indicate that while there may be abuses of the law, as there are of all laws everywhere, by and large it has been applied across the board to all organizations in receipt of foreign financial backing.

It is clear that the US agenda, under the cover of “democracy promotion” and “NGO strengthening” is to weaken the political establishment in Russia through various soft power means, with Alekseyeva as the symbolic matriarch of the human rights complex in Russia. But what of Putin’s government? Why should they acquiesce to the demands of Russian liberals and allow Alekseyeva onto the Presidential Council for Human Rights?

The Russian Strategy

Moscow is clearly playing politics and the public perception game. The government is very conscious of the fact that part of the Western propaganda campaign is to demonize Putin and his government as “authoritarian” and “violators of human rights.” So by allowing the figurehead of the movement onto the most influential human rights-oriented body, Moscow intends to alleviate some of that pressure, and take away one of the principal pieces of ammunition for the anti-Russia propagandists.

But there is yet another, and far more significant and politically savvy reason for doing this: accountability. Putin is confident in his position and popularity with Russians so he is not at all concerned about what Alekseyeva or her colleagues might say or do on the Council. On the other hand, Putin can now hold Russian liberals accountable for turning a blind eye to the systematic violations of human rights by the Kiev regime, particularly in Donbass.

One of the primary issues taken up by the Presidential Council for Civil Society and Human Rights in 2014 was the situation in Ukraine. In October 2014, President Putin, addressing the Council stated:

[The developments in Ukraine] have revealed a large-scale crisis in terms of international law, the basic norms of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. We see numerous violations of Articles 3, 4, 5, 7 and 11 of the 1948 UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights and of Article 3 of the Convention on Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide of December 9, 1948. We are witnessing the application of double standards in the assessment of crimes against the civilian population of southeastern Ukraine, violations of the fundamental human rights to life and personal integrity. People are subjected to torture, to cruel and humiliating punishment, discrimination and illegal rulings. Unfortunately, many international human rights organisations close their eyes to what is going on there, hypocritically turning away.

With these and other statements, Putin placed the issue of Ukraine and human rights abuses squarely in the lap of the council and any NGOs and ostensible “human rights” representatives on it. With broader NGO representation, it only makes it all the more apparent. It will now be up to Alekseyeva and Co. to either pursue the issues, or discredit themselves as hypocrites only interested in subjects deemed politically damaging to Moscow, and thus advantageous to Washginton. This is a critical point because for years Russians have argued that these Western-funded NGOs only exist to demonize Russia and to serve the Western agenda; the issue of Ukraine could hammer that point home beyond dispute.

And so, the return of Alekseyeva, far from being a victory for the NGO/human rights complex in Russia, might finally force them to take the issue of human rights and justice seriously, rather than using it as a convenient political club to bash Russians over the head with. Perhaps Russian speakers in Donetsk and Lugansk might actually get some of the humanitarian attention they so rightfully deserve from the liberals who, despite their rhetoric, have shown nothing but contempt for the bleeding of Donbass, seeing it as not a humanitarian catastrophe, but a political opportunity. Needless to say, with Putin and the Russian government in control, the millions invested in these organizations by Washington have turned out to be a bad investment.

Eric Draitser is an independent geopolitical analyst based in New York City, he is the founder of StopImperialism.org and OP-ed columnist for RT, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.

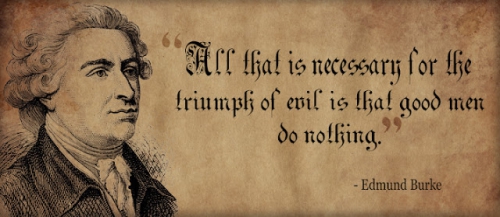

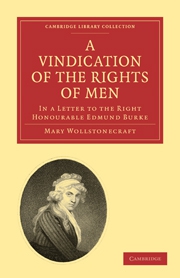

Vooreerst is het belangrijk om op te merken dat sommigen een schijnbare paradox vaststellen bij Burkes gedachtegoed. Zo was hij enerzijds een fervente criticus van het Britse koloniale bestuur in Indië en ondersteunde hij de Amerikaanse revolutionairen in hun onafhankelijkheidsstrijd, anderzijds was hij een fervente tegenstander van de Franse revolutionairen. De meeste auteurs wijzen echter op de continuïteit die men in deze attitudes aantreft, vooral wanneer men nauwgezet de Reflections on the revolution in France (1790) erop naleest. In dit werk, waarvoor hij zo bekend (of berucht) is geworden als vader van het moderne politieke conservatisme, maakt hij een duidelijk onderscheid tussen de traditie van de (Engelse) Glorious Revolution (1688) (en die hij ook terugvond bij de Amerikaanse revolutie) en de Franse revolutionairen van 1789 en nadien.

Vooreerst is het belangrijk om op te merken dat sommigen een schijnbare paradox vaststellen bij Burkes gedachtegoed. Zo was hij enerzijds een fervente criticus van het Britse koloniale bestuur in Indië en ondersteunde hij de Amerikaanse revolutionairen in hun onafhankelijkheidsstrijd, anderzijds was hij een fervente tegenstander van de Franse revolutionairen. De meeste auteurs wijzen echter op de continuïteit die men in deze attitudes aantreft, vooral wanneer men nauwgezet de Reflections on the revolution in France (1790) erop naleest. In dit werk, waarvoor hij zo bekend (of berucht) is geworden als vader van het moderne politieke conservatisme, maakt hij een duidelijk onderscheid tussen de traditie van de (Engelse) Glorious Revolution (1688) (en die hij ook terugvond bij de Amerikaanse revolutie) en de Franse revolutionairen van 1789 en nadien.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg