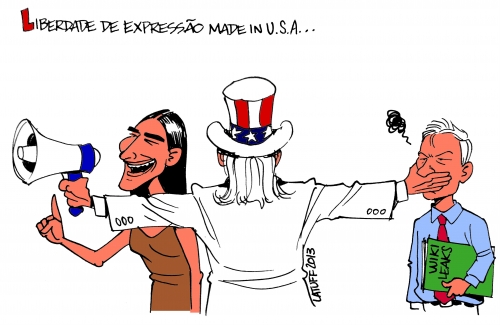

It’s time to call it: Democracies across the West are at an inflection point on free speech, and it’s not clear which way things will go on this issue in the next 20 or 30 years. In some cases, ostensibly liberal governments have already made moves to police and suppress what they deem unacceptable speech; in others, rigid political binaries have threatened to crowd out traditions of free inquiry and debate. All too often, it seems not to matter what is said in an argument but rather who says it and how it was said.

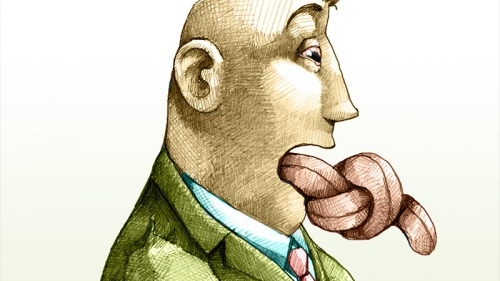

Superseding this once-proud tradition of free speech, empiricism, and free inquiry is calculating, cautious, self-censoring phraseology. And when people do express unorthodox views, it is often in hushed tones, out of fear that an overheard comment could kill their career and get them ostracized from polite society. A December 2018 Rasmussen Reports poll found that today only 26 percent of American adults believe they have true freedom of speech, while 68 percent think they have to be careful not to say something politically incorrect to avoid getting in trouble. In 1990 there were approximately 75 “hate speech” codes in place at U.S. colleges and universities; just one year later the number had swelled to more than 300 before spreading like a brushfire thereafter. According to the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) in 2018, 90 percent of American universities maintain at least one policy that either restricts protected speech or could easily be interpreted as doing so. Meanwhile in Europe, Germany unveiled in 2017 a new law, known locally as NetzDG, which included massive fines for social media networks that are insufficiently diligent in policing “hate speech” on their platforms. In 2018 Paris followed Berlin’s lead by toughening its laws on “hate speech” on social media. The same year a YouGov poll in the United Kingdom found that significantly more British voters (48 percent vs. 35 percent) believed that there were “many important issues these days where people are not allowed to say what they think.” Last but not least, a 2019 report to the Council of Europe concluded that European press freedom was more fragile today than at any time since the end of the Cold War, given the rise of attacks on and intimidation of journalists. In short, the abridgement of this most fundamental democratic freedom to speak one’s mind appears to have become the norm across the West, as though our elites and governments were rushing headlong down the road to a new dystopia. How did we get here?

Superseding this once-proud tradition of free speech, empiricism, and free inquiry is calculating, cautious, self-censoring phraseology. And when people do express unorthodox views, it is often in hushed tones, out of fear that an overheard comment could kill their career and get them ostracized from polite society. A December 2018 Rasmussen Reports poll found that today only 26 percent of American adults believe they have true freedom of speech, while 68 percent think they have to be careful not to say something politically incorrect to avoid getting in trouble. In 1990 there were approximately 75 “hate speech” codes in place at U.S. colleges and universities; just one year later the number had swelled to more than 300 before spreading like a brushfire thereafter. According to the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) in 2018, 90 percent of American universities maintain at least one policy that either restricts protected speech or could easily be interpreted as doing so. Meanwhile in Europe, Germany unveiled in 2017 a new law, known locally as NetzDG, which included massive fines for social media networks that are insufficiently diligent in policing “hate speech” on their platforms. In 2018 Paris followed Berlin’s lead by toughening its laws on “hate speech” on social media. The same year a YouGov poll in the United Kingdom found that significantly more British voters (48 percent vs. 35 percent) believed that there were “many important issues these days where people are not allowed to say what they think.” Last but not least, a 2019 report to the Council of Europe concluded that European press freedom was more fragile today than at any time since the end of the Cold War, given the rise of attacks on and intimidation of journalists. In short, the abridgement of this most fundamental democratic freedom to speak one’s mind appears to have become the norm across the West, as though our elites and governments were rushing headlong down the road to a new dystopia. How did we get here?

For decades now, the freedom to speak and argue—the most fundamental right of a free people—has been under assault by neo-Marxist advocates of a “more just society.” But it is only recently that their efforts have succeeded in shutting down an ever-widening range of venues of public debate: first in academia, then in the media, and of late in politics. Today the fundamental right to free speech is under threat not just from speech codes—that is, from proscriptions on what cannot be said—but also increasingly from prescriptive rules about what one must say, as though perfunctory condemnations of Western history were the price of admission to public debate.

Why are societies in Europe and America seemingly intent on suppressing the fundamentally democratic impulses to speak freely, to err, to debate, and even to offend so that, through it all, we might come to learn what passes the common sense test and possibly arrive at a larger national consensus on policy? When did ideological allegiance (liberal vs. illiberal) become a litmus test for what constitutes appropriate public discourse? And how did we get to the point where political expressions of concern for the economic and social welfare of the nation’s own is “xenophobia,” and where the only praiseworthy use of American power is to unconditionally embrace globalization or save the planet by signing onto high-minded but ultimately unenforceable declarations of virtuous intent? Why is it that in Europe today the traditional generosity of its people is all but taken for granted, while that same citizenry’s desire to ensure its own welfare and security, and to transmit its cultural inheritance to the next generation, is often reviled as intolerance by the intelligentsia, politicians, and the media?

The roots of our growing unfreedom were planted in the late 1960s, but only today can we truly appreciate the extent to which the ideas of that era deconstructed our democratic culture. This latest neo-Marxist lurch toward unfreedom happened in the span of a single generation, the result of a cultural unmooring during which conservatives seem to have lost their sense of caution, and liberals their collective mind. Today it is not uncommon to hear that the West itself is—as I was recently told—merely a “cultural construct of the early 20th century,” and that truth requires little empirical testing but is instead dependent on the identity of the individual who expresses it.

Ironically, this latest assault against the foundational values of our democratic tradition was exacerbated by arguably the greatest ideological triumph in the history of the West—and, in hindsight, also our most dangerous moment. The year was 1990—the first post-communist government had already been formed in Poland a year before, the Hungarians had opened their borders to allow refugees from East Germany to escape, and the Czechs and Slovaks had gathered in Wenceslas Square to tell the communist mafia that it was time to leave. Then the Berlin Wall came down and the Germans held their breath, hoping against hope that the once impossible dream of reunification would actually come true. On both sides of the Atlantic we cheered the annus mirabilis, exulting in the sight of this utter and seemingly irrevocable triumph of democracy—this ultimate consummation of American leadership and the West’s expenditure of blood and treasure to stop communism and preserve and expand liberty.

Indeed, both Americans and Europeans had every reason to celebrate. The world seemed perfectly poised to surf a new tsunami of freedom. History was on our side—or at least so claimed a plethora of op-eds, scholarly articles, and talking heads on television. At the time it seemed natural to many a commentator that what was believed to be universal would soon eclipse the national. The rules and institutions of Western-style democracy had proved their ability to cross the boundaries of culture now that a heterogeneous mix of countries had cast aside the Soviet yoke to take them up. Now that all of Europe had affirmed the value of freedom, was it not obvious that it would conquer the globe? The right to national self-determination was not so much discarded as allegedly transcended.

And yet the moment of the Soviet collapse carried a hidden threat that, in less than three decades, would deepen our divisions and weaken the foundations of individual liberty. Our sense of victory contained within it the seeds of arguably the greatest peril the West has ever confronted: the ideological certitude—not just on the Left—that we had cracked the code of the human condition and could get on with the work of perfecting both the individual and society.

And yet the moment of the Soviet collapse carried a hidden threat that, in less than three decades, would deepen our divisions and weaken the foundations of individual liberty. Our sense of victory contained within it the seeds of arguably the greatest peril the West has ever confronted: the ideological certitude—not just on the Left—that we had cracked the code of the human condition and could get on with the work of perfecting both the individual and society.

With the implosion of the Soviet Union we lost an enemy whose society was a living example of what projects aimed at re-engineering human nature were likely to yield: the loss of liberty, followed by repression and terror. Once the toxic Bolshevist experiment that had cost millions of lives and created unspeakable human misery was (at least in Europe) no more, the temptation of triumphalism proved too alluring. Since it seemed plausible on a basic level that liberal market capitalism had overpowered communism, it followed that there were no limits to what institutional and market reforms could achieve, especially once one discounted variables like culture and history as explanations for why liberal democracy had flourished in some societies and not others. It seemed that all the post-Cold War wave had to do to succeed was to go global. And so at its moment of triumph the West fell victim to a post-Enlightenment delusion of the perfectibility of man.

Yet the Soviet collapse also empowered neo-Marxists and fellow-progressives in the West to turn inward and focus on the “enemy within,” namely, that of the “system.” Without a tangible reminder of what efforts to re-engineer humanity had produced in Europe and elsewhere, it became possible for the ideologically committed to construct a narrative of what “true socialism” could have achieved if only the Stalinists and Maoists had not corrupted the collectivist dream. At the same time, the business community, no longer tamed by a once powerful sense of national solidarity, grew besotted with spurious claims about the “inevitable logic of the market.” Many among America’s policy and business elites argued that off-shoring the U.S. supply chain to Asia would not only make us rich but would also lead to that region’s export-driven modernization and eventual democratization. They told us that in the era of globalization, export-driven modernization would inevitably lift underdeveloped economies out of poverty, leading to the rise of an educated, empowered middle class that would demand representative government. Even today some continue to cling to this argument, against all evidence to the contrary.

Unfortunately, it is no exaggeration to say that freedom is waning across the West—not because foreign armies have defeated us in battle, or because all of our wealth has been drained by an alien economic power. Rather, the West is increasingly at risk of becoming “post-democratic” because its most basic foundational values of free expression and the liberty and sovereignty of the individual are being banished from the public agora. Discourse at American colleges and universities today more closely resembles that of the notorious Artek indoctrination camp for young Soviet pioneer activists than the “discussion, collaboration, and enlightenment” Thomas Jefferson envisioned when he conceived of the University of Virginia. In both Europe and America those with aspirations for professional attainment in academia, the corporate world, or the media must increasingly bow to the dominant orthodoxies and purge their speech of all incorrect phrases, with the goal of ultimately cleansing their mind of impure thoughts.

Unmoored from its cultural heritage and increasingly ignorant of its history, the West is fragmenting along racial, ethnic, and ideological lines. In the United States the process is well under way of transforming “e pluribus unum” into an American Balkans in which warring groups squabble over past grievances—real and imagined—and where a sense of patriotism and the mutuality of obligation so fundamental to a nation under a republican form of government is being purged from the culture. Here America is not alone, as similar undercurrents of unfreedom are deconstructing some of the oldest political traditions in Europe.

With freedom of speech under assault, the West, both as a polity and as a distinct cultural inheritance, is in the throes of a fundamental battle for the survival of its democratic traditions. It is time for all of us to stand up for liberty. And to do so out loud.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg