mercredi, 14 août 2024

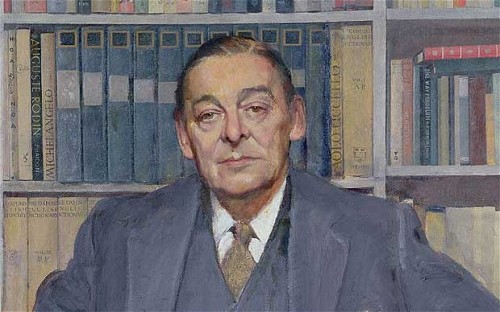

Thomas Stearns Eliot, quand la vraie poésie et la grande politique se rencontrent

Thomas Stearns Eliot, quand la vraie poésie et la grande politique se rencontrent

par Gennaro Malgieri

Source: https://www.destra.it/home/thomas-stearns-eliot-quando-vera-poesia-e-grande-politica-sincontrano/

Si la politique est encore capable d'inventer, comme la poésie, des suggestions qui pénètrent l'âme des gens et qui, en même temps, répondent aux questions les plus complexes que la société d'abondance pose constamment et impérieusement, elle remplit sa tâche, elle se donne un sens. C'est lorsque cela ne se produit pas que la politique se ferme, perd sa fonction, se retire. Sa crise se résume dans cette notation qui résume le sentiment d'une tragédie collective car sans politique, comme sans poésie, les peuples sont soumis à la domination des haines élémentaires qui se déchaînent dans l'enclos tribal auquel se réduit la nation, la communauté. Et le conflit se nourrit d'instincts irrésistibles parce qu'il n'est pas culturellement régulé par une idée, par un principe qui rende l'affrontement acceptable. Le point de chute est le nihilisme : un néant indistinct dans lequel les civilisations se dissolvent. La politique, comme la poésie, est une science de l'âme qui repose sur des valeurs, des sentiments primaires et des raisons qui renvoient à une vision de l'organisation sociale fondée sur la centralité de la personne et de sa dignité. Tout cela repose sur deux piliers: l'autorité et la liberté.

J'y pensais il y a quelques jours, en réfléchissant au long chemin parcouru par les espaces politiques de notre pays qui ont essayé de s'affiner pour coexister afin d'interpréter l'Italie profonde et de lui donner le souffle dont elle a besoin. Un souffle qui a le goût de la poésie. Car le souffle de l'unité de la nation italienne est séculaire et ne s'épuise pas dans la dimension étatique, qui est un acquis minimal, mais trouve sa place dans une âme que, pour nous comprendre, nous appelons identité.

En pensant à tout cela, je me suis souvenu d'une réflexion de Thomas Stearns Eliot contenue dans l'essai The Idea of a Christian Society (= L'idée d'une société chrétienne). Le poète anglo-américain notait : "Pendant longtemps, nous n'avons cru qu'aux valeurs dérivées d'une vie basée exclusivement sur la technologie, le commerce et les grandes villes: il est donc temps de nous confronter aux dimensions éternelles sur la base desquelles Dieu nous permet de vivre sur cette planète. Et, sans romantiser la vie sauvage, on pourrait aussi avoir l'humilité d'observer comment, dans certaines sociétés que nous jugeons primitives ou arriérées, fonctionne un système socio-religieux-artistique qui mériterait d'être imité à un niveau plus élevé. Nous avons été habitués à voir le "progrès" toujours comme une réalité monolithique, et nous n'avons pas encore appris que ce n'est qu'au prix d'un effort et d'une discipline plus grands que ceux que la société a jusqu'à présent jugé nécessaire de s'imposer, que l'on peut acquérir des connaissances matérielles et du pouvoir sans perdre la sagesse et la vigueur spirituelles".

La tentative à laquelle Eliot nous renvoie est, implicitement, celle de re-consacrer, si je puis m'exprimer ainsi, la politique en la tirant des bas-fonds de l'occasionnel pour en faire un projet de vie se référant au peuple, à ses besoins, à ses ambitions. Et un tel "miracle" ne peut se produire que si nous gardons à l'esprit que la tradition, les racines, le lien identitaire qui nous fait participer à une réalité historiquement et spirituellement définie ont la force de se lier aux dynamiques de la modernité sans se déformer, sans s'annuler en elles. L'idée d'une société organique dans laquelle toutes les composantes jouent le rôle qui leur revient doit donc être à la base d'une politique culturellement équipée pour favoriser l'intégration des deux besoins afin de donner au peuple une dimension dans laquelle il puisse se reconnaître. En d'autres termes, la technique n'est pas tout. En l'absolutisant, on détruit non seulement l'âme du peuple, mais la Planète même dont nous sommes les usufruitiers. L'équilibre entre l'utilisation des outils de l'intelligence et la préservation des raisons de l'esprit individuel et de celui des nations est, je crois, la "clé" qui ouvre la voie à la modernité sans se laisser engloutir par elle.

Un mouvement politique qui sait gérer une matière aussi incandescente, en Italie, ne peut opérer qu'en bouleversant les appartenances auxquelles ses composantes sont liées pour les traduire en une identité nouvelle, fondée précisément sur les exigences rappelées ici. Et l'on ne voit pas pourquoi cela ne se produirait pas, étant donné que les sujets auxquels nous nous référons ont dans leur code génétique les éléments qui justifient leur fusion si l'on considère l'intérêt plus général, qui est de créer les conditions d'une nouvelle saison, que l'on espère longue, au cours de laquelle la communauté nationale renaîtra avant tout sur le plan culturel.

Cela signifie l'abandon définitif de l'idéologisation de l'existence et la construction de structures sociales qui répondent aux besoins profonds des individus et de la collectivité. Mais cela signifie aussi se préparer au dialogue avec les "autres" cultures, ce qui est scandaleux pour ceux qui sont habitués, hélas, à penser seuls. Non, nous ne sommes pas seuls. Nous le devenons parce que nous sommes enfermés dans des schémas défensifs, sans même imaginer qu'une plus grande conscience identitaire pourrait résulter de l'ouverture. Et si les identités des peuples sont pensées ensemble et non de manière conflictuelle, même l'idée de la disparition de telle ou telle civilisation est appelée à reculer.

Un mouvement novateur, programmatiquement voué à la rupture (et rien n'est plus disruptif que le défi de construire un ensemble où tradition et modernité se tiennent la main), aspirera-t-il à conduire cette révolution culturelle ou tentera-t-il de préserver de petites rentes de situation pour survivre ? La politique, quand elle est grande, se rapproche de la poésie. Et son chemin peut même être aussi passionnant qu'il l'était à l'époque des constructions extraordinaires qui marquent encore notre civilisation. Quand les hommes politiques créaient et que les hommes ne se sentaient pas asservis, mais participaient aux grandes aventures de l'esprit.

18:52 Publié dans Littérature, Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, lettres, littérature anglo-américaine, lettres anglo-américaines, thomas stearns eliot, t. s. eliot, philosophie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 24 octobre 2023

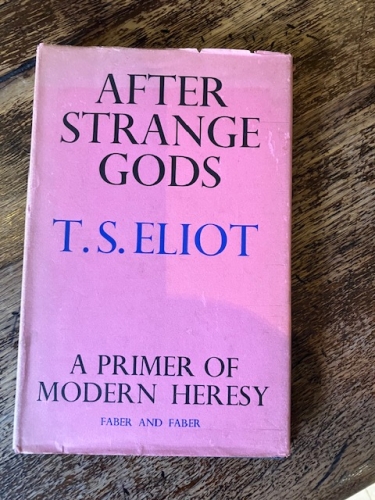

T.S. Eliot - Après les dieux étranges

T.S. Eliot - Après les dieux étranges

par Joakim Andersen

Source: https://motpol.nu/oskorei/2023/10/09/t-s-eliot-after-strange-gods/

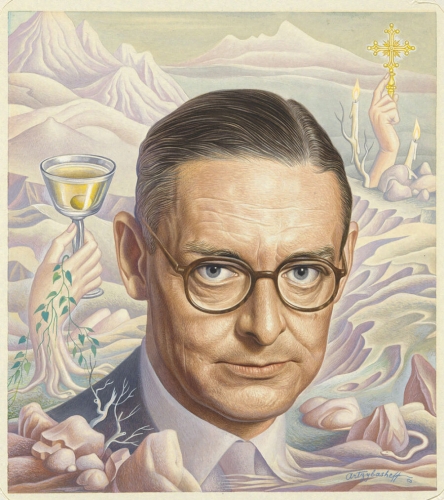

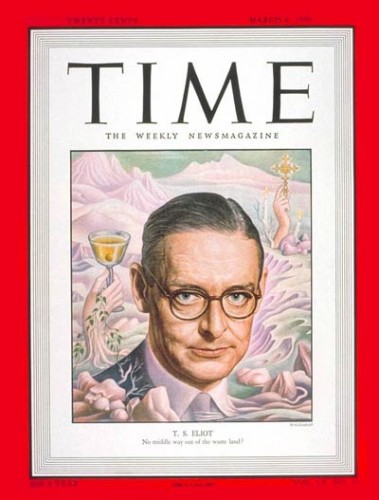

T.S. Eliot (1888-1965) est l'un des plus grands poètes du 20ème siècle ; avec des œuvres telles que The Waste Land et The Hollow Men, il a à la fois confirmé et actualisé la valeur et les possibilités de la poésie. Par exemple, certains types humains de la fin des temps modernes sont saisis dans des pièces telles que "les hommes creux, les hommes empaillés" (the hollow men, the stuffed men), des aspects du monde de la fin des temps modernes dans "c'est ainsi que le monde se termine, non pas avec un bang, mais avec un gémissement" (not with a bang but with a whimper). Eliot évoluait souvent dans un environnement de critique de la civilisation ou plutôt de diagnostic avec une perspective de droite où l'on trouve aussi Conrad, Jung et C.S. Lewis, entre autres. Il combinait "un esprit catholique, un héritage calviniste et un tempérament puritain", et était proche d'Ezra Pound, entre autres.

Parmi les œuvres les moins connues d'Eliot, After Strange Gods (1933) est basé sur une série de conférences. Il y développe les thèmes qu'il avait abordés dans Tradition and the Individual Talent (La tradition et le talent individuel). Eliot utilise les concepts d'une manière différente de celle, par exemple, d'Evola ; dans le cas d'Eliot, la "tradition" correspond le plus étroitement à la "culture" selon l'acception suédoise, mais cela ne rend pas ses arguments moins pertinents. Sa définition de la tradition est organique et holistique : "ce que j'entends par tradition implique toutes ces actions habituelles, ces habitudes et ces coutumes, du rite religieux le plus important à notre façon conventionnelle de saluer un étranger, qui représentent la parenté de sang des "mêmes personnes vivant au même endroit"". Cette définition s'applique, entre autres, aux discussions sur la question de savoir si les hommes et les femmes se serrent la main, où l'alternative islamique peut être à la fois légitime et compréhensible, mais ne représente toujours pas la parenté de sang des "mêmes personnes vivant au même endroit" en Suède.

Eliot a discuté des changements dans la tradition au fil du temps, des dangers de s'enfermer dans des formes mortes et dans une "tradition sans intelligence". Il évoque ici Lampedusa ainsi que les révolutionnaires conservateurs : l'essence ou l'âme d'un certain groupe peut prendre différentes formes dans différentes situations historiques, tout en restant reconnaissable. "Tout doit changer si l'on veut que tout reste comme avant. En même temps, Eliot s'est penché sur les conditions de la tradition et sur la possibilité de perdre une tradition. Cette dernière s'était produite dans une grande partie des États-Unis, mais Eliot était plus favorable au Sud et à ses penseurs agrariens. À cet égard, il mentionne avec faveur le manifeste agraire sudiste I'll Take My Stand.

Les conditions de la tradition étaient notamment liées à l'homogénéité. Loin d'être un "multiculturaliste", Eliot a écrit que "lorsque deux ou plusieurs cultures existent au même endroit, elles sont susceptibles soit d'être farouchement conscientes d'elles-mêmes, soit de se dénaturer toutes les deux". L'homogénéité religieuse était également un avantage. On peut noter qu'Eliot s'est rapproché de la perspective du sang et du sol, son idéal étant la région "dans laquelle le paysage a été modelé par de nombreuses générations d'une même race, et dans laquelle le paysage, à son tour, a modifié la race pour lui donner son propre caractère". Eliot nous rappelle ici que la plupart des choses ont un prix. Vous pouvez avoir une immigration de masse avec des aliments exotiques, mais vous risquez de perdre votre tradition dans le processus. Il aborde également l'importance de l'équilibre entre la ville et la campagne, ainsi que les risques de l'industrialisation pour la tradition.

Un autre thème intéressant dans After Strange Gods concerne la relation entre l'artiste et la tradition. Eliot y constate que certains artistes se contentent de répéter des formes traditionnelles, même si "la tradition ne peut signifier l'immobilisme". Un phénomène plus moderne est l'innovation ou l'originalité pour elle-même, "une nouveauté généralement insignifiante, qui dissimule au lecteur non critique une banalité fondamentale". Une société sans tradition forte peut facilement développer une culture axée sur la nouveauté, l'excentricité et l'originalité, ce qui, selon Eliot, pourrait conduire à une focalisation sur le morbide, le malade et le mal. Il respectait D.H. Lawrence en tant qu'écrivain, mais notait que "la vision de cet homme est spirituelle, mais spirituellement malade". À notre époque, la description de personnes essentiellement basses et égoïstes pourrait jouer un rôle similaire (comparez les personnages de Tolkien et leurs motivations avec ceux de George R.R. Martin). Quoi qu'il en soit, l'approche d'Eliot consistant à appliquer des principes moraux à l'évaluation des œuvres littéraires est fructueuse, notamment en tant que complément à d'autres perspectives. L'obsession du "nouveau" et de "l'original" peut facilement conduire à présenter le "malade" comme intéressant ou authentique, et c'est là une prise de conscience durable. Adorno était ici, paradoxalement, plus proche de la critique plus traditionnelle de la société de consommation qu'Eliot, avec des formulations telles que "tout peut, en tant que nouveauté, dépouillée d'elle-même, être apprécié, tout comme le morphinomane engourdi finit par se tourner indistinctement vers n'importe quelle drogue, même l'atropine" et le concept précis de "fascination sans volonté".

Dans l'ensemble, il s'agit d'une lecture enrichissante. Eliot y aborde notamment la relation entre tradition et orthodoxie, l'importance relativement réduite du blasphème dans l'arsenal du Prince des Ténèbres et l'accent mis aujourd'hui sur la personnalité de l'artiste. Mais la compréhension des conditions de la tradition et de la fixation sur l'"original" est l'un des principaux avantages de ces conférences.

23:55 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : t. s. eliot, lettres, lettres américaines, littérature, littérature américaine, l |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 03 novembre 2014

Little Gidding

Little Gidding

By Christopher Pankhurst

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

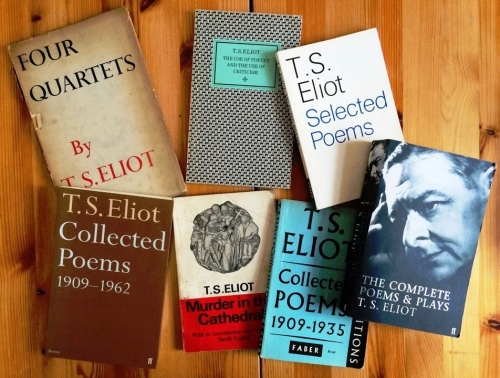

T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets can be considered amongst the greatest English poetry of the 20th century, and arguably amongst the greatest English poetry ever. The four poems meditate repetitively and brilliantly on man’s relationship to time and eternity, and posit a religious solution to the problem of man’s need for meaning in the face of death.

Eliot converted to Anglicanism and became a British subject in 1927. With this double conversion Eliot seemed to find access to a deeper and more rooted sense of spiritual identity. This provides the key to understanding the lines from Little Gidding, the last poem in the sequence: “So, while the light fails/ On a winter’s afternoon, in a secluded chapel/ History is now and England.” The Four Quartets can be read as a sort of metaphysical statement or better still as a sacred text. The great achievement of these poems is to crystallize difficult metaphysical concepts, particularly the intersection of the eternal with the temporal, in memorable and lasting images. Thus, the poems are themselves an intersection of the eternal into language, and a validation of their own theme.

The first poem of the sequence, Burnt Norton, begins by articulating the doubt that vexes the religious mind: “Time present and time past/ Are both perhaps present in time future/ And time future contained in time past./ If all time is eternally present/ All time is unredeemable.” This is the conundrum: if we escape from the narrow prison of egoic consciousness and intuit a higher sense of interconnection that transcends linear temporality then we begin to worry that everything has, in some sense, already happened, that everything is predetermined, and that free will counts for nothing. We see ourselves as, “Men and bits of paper, whirled by the cold wind/ That blows before and after time.” A larger perspective shrinks man and makes him seem like nothing more than a dead leaf blowing in the breeze. When man adopts this cosmic perspective he seems to lose all volition and meaning, the vastness of time reduces him to an unimportant and impotent detail, unworthy of note. This sense of diminishment undermines the religious imperative. Why worship God (eternity) when that very vastness itself makes us feel meaningless?

At a vulgar level religion provides simple answers and comfort for people. But Eliot is concerned here with a much higher level of understanding. It is an important issue because if religion cannot provide meaning at a serious intellectual level then it really is no more than a noble lie, fed to the masses to keep them supine. Eliot clearly senses that it is far more than this and he struggles with the question of how to read meaning into a perspective wherein “time is unredeemable.” By the final poem of the sequence, Little Gidding, he achieves a sense of resolution.

Little Gidding is a real place in Huntingdonshire and is closely associated with the English theologian Nicholas Farrar. Farrar was born in 1592 into a wealthy merchant family and he was intellectually precocious from an early age. After a short career in business and Parliament he left London and in 1625 moved to Little Gidding. At that time Little Gidding consisted of a run-down house and a chapel in a field. Farrar moved there with his mother, brother and sister, their children, and a few other people. About 30 people lived there and formed a close-knit religious community.

Little Gidding is a real place in Huntingdonshire and is closely associated with the English theologian Nicholas Farrar. Farrar was born in 1592 into a wealthy merchant family and he was intellectually precocious from an early age. After a short career in business and Parliament he left London and in 1625 moved to Little Gidding. At that time Little Gidding consisted of a run-down house and a chapel in a field. Farrar moved there with his mother, brother and sister, their children, and a few other people. About 30 people lived there and formed a close-knit religious community.

I was unaware of the association between Eliot’s Little Gidding and Nicholas Farrar until I read the chapter on Farrar in Colin Wilson’s Religion and the Rebel. Religion and the Rebel was Wilson’s successor to his debut book, The Outsider. Whereas the publication of The Outsider drew unbelievably glowing reviews, Religion and the Rebel was completely trashed and marked a decisive end to Wilson’s very brief moment in the critical sun. Reading the book now it is possible to understand why the critics hated it, although that is no excuse for their antipathy.

Wilson is influenced by both Oswald Spengler and Arnold Toynbee in elaborating a cyclic view of history. In The Outsider he had demonstrated how certain literary and philosophical figures from the 19th and 20th centuries had seen deeper into the problem of human existence than most artists. The “outsider” was the man who intuited a limitless sea of potential within the human psyche but who felt thwarted by the pettiness and contingency of existence.

In Religion and the Rebel, Wilson extrapolated his thesis to encompass aeonic stretches of civilizational time. This allowed him to argue that certain visionary figures who lived at a time of high civilizational health could integrate their higher sensibility into a more vigorous theological structure. Only with the decline of the civilization, and the attendant decline in religious vigor, did such men become alienated from the mainstream of spiritual life and acquire their outsider status.

Such a thesis strikes me as being not just sensible but ultimately compelling. Presumably the critics caught a sniff of metaphysical obscurantism; or perhaps they couldn’t stomach a cyclic view of history wherein Marx’s materialistic prophecies had no place. In any case, Wilson was soon suspected of some sort of ill-defined fascism, and his subsequent obsession with serial killers and the occult did nothing to return him to critical favor.

Of course, the popular backlash against Wilson’s thesis is exactly the sort of response you would expect if his thesis was correct. If Wilson and Spengler were correct, and the mid-20th century marked a period of spiritual poverty (the decline of the west), then you would expect a book like Religion and the Rebel to be met with incomprehension. Marxists would have balked at the importance given to visions and the powers of the human mind (or spirit), whilst Christians could not have accepted the ready conflation of their faith with other systems of philosophical enquiry. Wilson was falling between the cracks of 20th-century English thought and ensuring his own exile to outsider status.

Wilson’s interest in Nicholas Ferrar stems from the type of devotional community that Ferrar set up at Little Gidding. The entire community would cross the field to the chapel for worship three times a day: matins at 6 a.m., litany at 10 a.m., and evensong at 4 p.m. In addition, Ferrar set up a system of Gospel readings taking place every hour, so that the four Gospels would be read in their entirety each month. On top of all this, on a couple of nights each week after a four hour Psalter recital finishing at 1 a.m., Ferrar would spend the rest of the night in meditation and prayer.

Wilson notes, “It is true that the monastic temper is not a familiar one in the modern world and that, although millions of people may detest the routine of modern life and wish they could escape from it, they would hardly be willing to exchange it for the life of a monk.” But nonetheless, Ferrar had found one particular answer to the outsider’s problem: “he had set his own little corner of the world in order, and lived in that corner as if the rest of the world did not exist.”[1]

Wilson notes, “It is true that the monastic temper is not a familiar one in the modern world and that, although millions of people may detest the routine of modern life and wish they could escape from it, they would hardly be willing to exchange it for the life of a monk.” But nonetheless, Ferrar had found one particular answer to the outsider’s problem: “he had set his own little corner of the world in order, and lived in that corner as if the rest of the world did not exist.”[1]

For Eliot, Little Gidding represented more than this. At the end of The Dry Salvages, the third poem in the sequence, he presents the solution to the problem of being in time:

The hint half guessed, the gift half understood, is Incarnation.

Here the impossible union

Of spheres of existence is actual,

Here the past and future

Are conquered, and reconciled,

Where action were otherwise movement

Of that which is only moved

And has in it no source of movement-

Driven by dæmonic, chthonic

Powers.

Through the Incarnation of Christ, “the impossible union of spheres,” time is redeemed. The eternal is no longer an incomprehensibly vast expanse of predetermined actions but a condition of freedom and redemption that can be actualized within time:

But to apprehend

The point of intersection of the timeless

With time, is an occupation for the saint–

So, for some few holy men it is possible to actualize the eternal in time. It is with this resolution that Eliot concludes The Dry Salvages and moves on to Little Gidding.

Little Gidding begins with a description of a bright winter’s day when the hedgerow is covered in snow. The image creates a paradoxical impression of flowering in winter:

This is the spring time

But not in time’s covenant. Now the hedgerow

Is blanched for an hour with transitory blossom

Of snow

It is a momentary glimpse of temporal paradox. It serves merely as a poetic foreword to the real intention of the poem. We then approach the chapel at Little Gidding itself:

If you came by day not knowing what you came for,

It would be the same, when you leave the rough road

And turn behind the pig-sty to the dull facade

And the tombstone.

The tombstone is that of Nicholas Ferrar, blank, uninscribed, a sacred precursor to Abstract Expressionist painting. But this is not the sort of interpretation that Eliot would countenance. The value of Little Gidding the place derives from the holiness of the lives lived there and the disciplined, ordered urge to transcend the contingencies of time and place. Ferrar instituted a way of life at Little Gidding that was able to actualize the eruption of the eternal into time. And the only reason for pilgrimage to Little Gidding is to try to participate in some way in this practice of worship:

You are not here to verify,

Instruct yourself, or inform curiosity

Or carry report. You are here to kneel

Where prayer has been valid. And prayer is more

Than an order of words, the conscious occupation

Of the praying mind, or the sound of the voice praying.

And what the dead had no speech for, when living,

They can tell you, being dead: the communication

Of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living.

Here, the intersection of the timeless moment

Is England and nowhere. Never and always.

Here, Eliot is suggesting that this small and insignificant chapel is one place where the Holy Spirit descended. The language echoes Acts of the Apostles, “And when the day of Pentecost was fully come, they were all with one accord in one place. And suddenly there came a sound from heaven as of a rushing mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting. And there appeared unto them cloven tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance.” In Eliot’s poem the dead speak with Pentecostal fire and actualize the timeless moment. The holy fire is the symbol of the eternal and is opposed to the fire of hell which is the destructive fire of temporality, the distracted, egoic consciousness that cannot begin to intuit the notion that there might be something more to life than material manifestation. This destructive fire devours time because it is the manifestation of a mind that can only perceive a linear progression moving towards death, each second consuming reality in an endless cremation. The fire of the Holy Spirit, on the other hand, is the voice of the dead, the triumph over mundane time and the redemption of all time in the timeless moment.

And the possibility of this intrusion of the eternal into time is predicated on the Incarnation. So, for Eliot, escape from the temporal prison is only possible because the eternal (God) manifested in history and created the possibility for actualizing this “impossible union” between distinct “spheres of existence.” Nicholas Ferrar’s solution can only be achieved through the disciplined pursuit of holiness, and even then it must take the divine Incarnation as its precondition.

At the conclusion of his chapter on Nicholas Ferrar, Wilson is critical of Ferrar’s solution: “We may feel that there is much to find fault with in the Little Gidding way of life. The objection to it is the same as the objection to Mr. Eliot’s embracing of Anglicanism: that the Outsider must not surrender his reason to some ‘historical’ fact. For ultimately, history does not matter.”[2] This objection is one with which I both agree and disagree. To insist that the possibility of redemption from time is dependent upon the Incarnation of Christ seems to me to belong to the sphere of the noble lie. In other words, whilst I have no problem with the Incarnation being an article of faith for Christian believers it cannot be an absolute and universal requirement for the possibility of transcending mundane time.

However, in stating that, “history does not matter,” Wilson overstates his case. He evidently does so because he believes so strongly that the human individual has the potential to overcome his limitations regardless of the phase of the civilizational cycle he happens to be living in. But his error is to focus too closely on the individual at the expense of the culture as a whole. This is entirely typical of Wilson’s existentialism and his interest in the potential powers of human consciousness. He is interested in what the intellectual and artistic elite are capable of achieving at the highest level and his hope seems to be for a future state of global transformation of individuals into Nietzschean overmen. As he puts it elsewhere in Religion and the Rebel the problem is, “how to make our whole civilization think like the Outsider.”[3] But this is not the problem. Trying to make all members of society think like outsiders is an inorganic solution to an organic problem. It is also teleologically similar to Christian Messianism and Marxist utopianism and, in the hope for a future state of super-empowered men, Wilson has forgotten one of Spengler’s crucial lessons: we are tied to our own particular culture or civilization.

So, history does matter in a crucial sense. As the example of Little Gidding shows, particular acts of worship in a particular place can achieve intimations of immortality. But this sense of the eternal is not a sort of free floating universalist spirit. It emerges through the sanctification of place through particular acts of worship. History is important in this sense because the discipline of religious worship creates its own special accumulation of sanctity. It is what makes certain places holy. And one thing that all religious people agree on is that certain places are holy places. But the importance of history in this sense is very different from the insistence that Christ existed historically as an intersection of different dimensions.

There is, in fact, a certain paradox for many of us here. Those who do not accept the Incarnation of Christ as a point of historical singularity have to face the fact that it was a deep article of faith for most (almost all) of our ancestors for many centuries. If we then wish to venerate the past we have to admit that a great deal of it was predicated on this belief in the Incarnation. If we choose to simply overlook this fact we are slighting the sincere beliefs of the dead whom we profess to respect, and implementing a degree of discontinuity with the past. It is not a trivial problem.

Regardless, it is useful to bear in mind the example of Little Gidding when thinking about spiritual practice. Few of us would wish to go to the extremes that Nicholas Ferrar went to and some of us in any case would not want to emulate his Christianity. But for most of us we can still, with Eliot, meditate on those intimations of the eternal that sometimes fall upon us, those,

hints and guesses,

Hints followed by guesses; and the rest

Is prayer, observance, discipline, thought and action.

Notes

1. Colin Wilson, Religion and the Rebel (Salem: Salem House, 1984), 175.

2. Ibid., 177.

3. Ibid., 256.

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2014/10/little-gidding/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/t-s-eliot_crop.jpg

[2] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Nicholas_Ferrar.jpeg

[3] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/ColinWilson.jpg

00:09 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : colin wilson, t. s. eliot, lettres, littérature, littérature anglaise, lettres anglaises |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 19 juin 2013

Dichter der Tradition

Dichter der Tradition

von Prof. Paul Gottfried (Gastautor)

Ex: http://www.blauenarzisse.de/

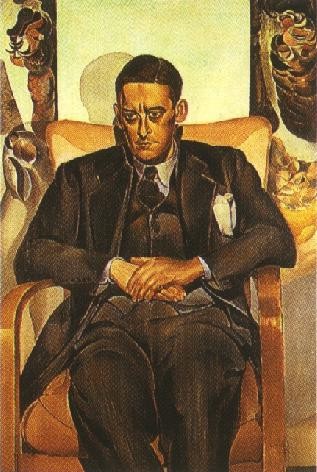

T S. Eliot verkörpert in Europa die US-amerikanische Spielart literarischer Moderne. Der Schriftsteller selbst sah sich im Dreiklang von „Monarchie, Klassizismus und einer anglokatholischen Einstellung”.

Der „Stockneuengländer” mit anglikanischen Vorfahren aus Boston kam 1888 in St. Louis/Missouri zur Welt und steuerte früh auf einen europäischen Bezugspunkt zu. 1914 reiste er nach Marburg und siedelte sich schließlich in Oxford an. Als Harvard-Absolvent mit einer schon bewährten literarischen Begabung brauchte der junge Autor des modernistischen Klassikers und Versepos The Waste Land von 1922 eine Lebens– und Mitwelt, in der er sich seelisch zuhause fühlen konnte. Der von ihm in seinem theoretischen Schrifttum hervorgehobene Dreiklang „Monarchie, Klassizismus und eine anglokatholischen Einstellung im theologischen Bereich“, bezeugt Eliots Suche nach einer allumfassenden, sinnstiftenden Identität.

Die englische Tradition

Was Thomas Stearns Eliot begrifflich und dichterisch herstellte, entsprang seiner Schöpferkraft, die unter anderem eine traumhafte, archaisierte politische und kulturelle Landschaft der Gegenwart als Folie heraufbeschwor. In seinem Gesamtwerk zeichnen sich seine immer wiederkehrenden Vergangenheitsbeschäftigung ab und – nicht weniger hervorstechend – sein Bedauern über den Verlust einer aristokratisch-priesterlichen Pracht.

Ein scharfsinniger Deuter des angloamerikanischen Dichters, Adrian Cunningham, betont Eliott Schwepunktsetzung auf die „englische Tradition“. Formelhaft und anhand des französischen Monarchisten Charles Maurras gelangte Eliot zu einem Verständnis der Tradition als geteiltem Erbgut, das er mit seiner kunstvoll konturierten englischen Vergangenheit in Verbindung brachte. Eliot ging diese intellektuelle Übung in seiner 1992 gegründeten Literaturzeitschrift Criterion an, ohne Rücksicht auf die Besonderheiten seiner eigenen Familienvergangenheit zu nehmen. Bei Eliots Zerlegung „des gewöhnlichen Handelns“ tritt wenig Erlebtes und Prägendes aus dem eigenen Elternhaus im mittleren Westen der USA heraus. Dabei wanderten seine angesehenen Vorfahren aus England aus und siedelten sich im 17. Jahrhundert in den amerikanischen Kolonien an.

Mehr Soziologie als Theologie

Wenn Eliot seine Glaubenslehre verteidigt, läuft seine Darlegung Cunningham zufolge eher „auf einen soziologischen als einen theologischen Standpunkt“ hinaus. Der Dichter verstand sie als Bestandteil der Idee einer „universalen Kirche“ im Kontext der römischen und orthodoxen Konfessionen. Nach dem strengen Katholiken Cuningham scheiterte das Verfahren in dem Maße, dass Eliot von einer selbstbezogenen Vorstellung ausging, ohne in einer wahren religiösen Tradition verankert zu sein.

Wenn Eliot seine Glaubenslehre verteidigt, läuft seine Darlegung Cunningham zufolge eher „auf einen soziologischen als einen theologischen Standpunkt“ hinaus. Der Dichter verstand sie als Bestandteil der Idee einer „universalen Kirche“ im Kontext der römischen und orthodoxen Konfessionen. Nach dem strengen Katholiken Cuningham scheiterte das Verfahren in dem Maße, dass Eliot von einer selbstbezogenen Vorstellung ausging, ohne in einer wahren religiösen Tradition verankert zu sein.

Seine Schaffensfreudigkeit wurde dauernd mit einer Kritik der Moderne verknüpft und zugleich mit dem Auftrag, eine für seine Lebensmission geeignete Tradition vorzufinden oder sich auszudenken. Cunningham betont Eliots Besorgnis über den ausufernden Relativismus, der ihn in seinem aus den Fugen geratenen Zeitalter erschütterte. Umso größer blieb Eliots Bedürfnis nach einem sittlichen Rettungsanker. Er trauerte um den Verlust ästhetischer Maßstäbe, die in einer noch erkennbar aristokratischen Kultur gediehen waren. Durch sein Werk wollte der Dichter diese glühend verehrte Vergangenheit versinnlichen.

Doch Eliots angenommene Identität und sein Festhalten an einer monarchistischen, hochkirchlichen Tradition hätte dessen Vorfahren kaum angesprochen. Im Gegensatz zu seinen calvinistischen, republikanisch gesinnten Ahnherren, die in die Neue Welt einwanderten, entschied sich Eliot für den Monarchismus und für die seine Wahltradition begleitende Dogmenlehre.

Verschlossenheit und Wandel

Daraus erwuchs ihm und der englischsprachigen Literatur im Zwanzigsten Jahrhundert ein großer Gewinn. In Dramen wie Murder in the Cathedral (1935) und der umfangreichen Lyrik verbirgt sich eine schöpferische Genialität, die Eliots steife und verkrampfte Außenwirkung Lügen straft. Wie seine angenommenen, englischen Mituntertanen des Königs hat Eliot oft eine sprichwörtliche Verschlossenheit bekundet. Das kam ihm zugute, als er mit einer Menge von Schwierigkeiten zu ringen hatte. Als seine erste Gattin, Vivienne, geisteskrank wurde, litt der Dichter und fühlte sich gedrängt, sie in ein Sanatorium einzuliefern.

Modernismus und vergangene Pracht

Bis heute tobt eine stürmische Kontroverse um die Frage, ob Eliot für seine junge temperamentvolle Frau hinlänglich sorgte und ihre Einweisung berechtigt war. Außer Zweifel steht, dass Eliot bis tief in seine mittleren Jahre hinein bedürftigen Umständen gegenüberstand. In einer Bank rackerte er sich tagsüber als Kassierer ab. Seine literarische Leidenschaft konnte er sich nur nachts und daher häufig übermüdet widmen. Trotz des unerwarteten Erlöses, der ihm dank The Waste Land zufiel, versiegte sein Wohlstand rasch. Eliot fehlte das Geld, sich ganz der Dichtkunst zuzuwenden. Erst als er 1948 mit dem Literaturnobelpreis geehrt wurde, zeichnete sich langsam ein Wandel ab.

Bemerkenswert bleibt, dass Eliot gerade in seine theologisch-politischen Schriften viel Mühe investierte. Wenn heute seine umständlichen Essays, etwa The Idea of a Christian Society (1939), nicht derart bekannt wie die Gedichte sind, dann muss beachtet werden, dass Eliot in seinen geschmacklichen und politisch-theologischen Aufsätzen seine mit Wehmut angehauchte Weltansicht am stärksten enthüllt. In seinen Gedichten tritt dagegen eine mit dem Modernismus verwachsene Schöpferkraft zutage, die ebenso auf neue literarische Ausdrucksmöglichkeiten vorausweist, wie sie in eine vergangene Pracht zurückführt.

Schon in seinen ersten bedeutenden, satirischen Gedichten, The Love Song of Alfred J. Prufrock, die bereits 1917 herauskamen, erschlossen sich einige Zeichen des Experimentierens mit Versformen, die die schon damals hervortretenden Modernisten kennzeichnete. Sie arbeiteten vor allem mit freien Versen und eingestreuten Glossen über die Verkommenheit der Massenkultur. Als Wegbereiter galten Leitfiguren wie Ezra Pound, Gottfried Benn, und Louis-Ferdinand Céline, die den Aufruf zur ästhetischen Mobilisierung mit konservativen oder rechten Zuneigungen verquickten.

Pietät und Märtyrerleiden

Im Gegensatz zum genialen Ezra Pound, der mit ihm die Erstfassung von The Waste Land umgearbeitet hatte, blieb Eliot aber von neuheidnischen Gedanken unberührt. Diese Zeitströmung, die im letzten Viertel des 19. Jahrhunderts einsetzte und mit Namen wie Nietzsche, D’Annunzio, und Pound in die kulturelle Tradition einzog, prallte von Eliot gänzlich ab. Aus seinen Dichtungen und Schauspielen entströmt, wie bei dem katholischen, französischen Schriftsteller Paul Claudel (1868 — 1955), ein betont christlicher Geist. In etlichen Schöpfungen wie Ash Wednesday (Aschermittwoch, 1930) und Murder in the Cathedral bleiben die Thematiken unverkennbar anglokatholisch.

Auch bei Eliots Bewunderern erschöpft sich manchmal die menschliche Geduld, wenn Eliot seine Pietät wiederholt unterstreicht. In den Schauspielen Murder in the Cathedral, das die Tötung des Erzbischofs Thomas Beckett auf Befehl des ihm entfremdeten Königs Heinrich II. schildert sowie The Cocktail Party (1948), das das Befestigen einer Missionarin an einem Ameisenhügel irgendwo in Afrika nacherzählt, zeigt sich die finstere Seite des Gläubigen. Märtyrerleiden übten auf Eliot zeitlebens eine große Faszination aus. Zweifelsohne, Eliot ging konsequent einen ganz eigenen Weg. Von anderen ließ er sich unterrichten, ohne ihnen zu verfallen.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : t. s. eliot, littérature, lettres, lettres anglaises, littérature anglaise, tradition, paul gottfried |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 23 janvier 2013

T. S. Eliot reads "Journey of the Magi"

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : t. s. eliot, littérature, lettres, lettres anglaises, littérature anglaise, angleterre, états-unis, poésie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 22 janvier 2013

"The Hollow Men" by T.S. Eliot (poetry reading)

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, littérature anglaise, lettres, lettres anglaises, angleterre, états-unis, t. s. eliot |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 02 décembre 2012

Eliot, Pound, and Lewis: A Creative Friendship

Eliot, Pound, and Lewis: A Creative Friendship

It may be a source of some pride to those of us fated to live out our lives as Americans that the three men who probably had the greatest influence on English literature in our century were all born on this side of the Atlantic. One of them, Wyndham Lewis, to be sure, was born on a yacht anchored in a harbor in Nova Scotia, but his father was an American, served as an officer in the Union Army in the Civil War, and came from a family that has been established here for many generations. The other two were as American in background and education as it is possible to be. Our pride at having produced men of such high achievement should be considered against the fact that all three spent their creative lives in Europe. For Wyndham Lewis the decision was made for him by his mother, who hustled him off to Europe at the age of ten, but he chose to remain in Europe, and to study in Paris rather than to accept the invitation of his father to go to Cornell, and except for an enforced stay in Canada during World War II, spent his life in Europe. The other two, Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot, went to Europe as young men out of college, and it was a part of European, not American, cultural life that they made their contribution to literature. Lewis was a European in training, attitude and point of view, but Pound and Eliot were Americans, and Pound, particularly, remained aggressively American; whether living in London or Italy his interest in American affairs never waned.

The lives and achievements of these three men were closely connected. They met as young men, each was influenced and helped by the other two, and they remained friends, in spite of occasional differences, for the rest of their lives. Many will remember the picture in Time of Pound as a very old man attending the memorial service in Westminster Abbey in 1965 for T.S. Eliot. When Lewis, who had gone blind, was unable to read the proofs of his latest book, it was his old friend, T.S. Eliot who did it for him, and when Pound was confined in St. Elizabeth’s in Washington, Eliot and Lewis always kept in close touch with him, and it was at least partly through Eliot’s influence that he was finally released. The lives and association of these three men, whose careers started almost at the same time shortly before World War I are an integral part of the literary and cultural history of this century.

The careers of all three may be said, in a certain way, to have been launched by the publication of Lewis’ magazine Blast. Both Lewis and Pound had been published before and had made something of a name for themselves in artistic and literary circles in London, but it was the publication in June, 1914, of the first issue of Blast that put them, so to speak, in the center of the stage. The first Blast contained 160 pages of text, was well printed on heavy paper, its format large, the typography extravagant, and its cover purple. It contained illustrations, many by Lewis, stories by Rebecca West and Ford Maddox Ford, poetry by Pound and others, but it is chiefly remembered for its “Blasts” and “Blesses” and its manifestos. It was in this first issue of Blast that “vorticism,” the new art form, was announced, the name having been invented by Pound. Vorticism was supposed to express the idea that art should represent the present, at rest, and at the greatest concentration of energy, between past and future. “There is no Present – there is Past and Future, and there is Art,” was a vorticist slogan. English humour and its “first cousin and accomplice, sport” were blasted, as were “sentimental hygienics,” Victorian liberalism, the Royal Academy, the Britannic aesthete; Blesses were reserved for the seafarer, the great ports, for Shakespeare “for his bitter Northern rhetoric of humour” and Swift “for his solemn, bleak wisdom of laughter”; a special bless, as if in anticipation of our hairy age, was granted the hairdresser. Its purpose, Lewis wrote many years later, was to exalt “formality and order, at the expense of the disorderly and the unkempt. It is merely a humorous way,” he went on to say, “of stating the classic standpoint as against the romantic.”

The second, and last, issue of Blast appeared in July, 1915, by which time Lewis was serving in the British army. This issue again contained essays, notes and editorial comments by Lewis and poetry by Pound, but displayed little of the youthful exuberance of the first – the editors and contributors were too much aware of the suicidal bloodletting taking place in the trenches of Flanders and France for that. The second issue, for example, contained, as did the first, a contribution by the gifted young sculptor Gaudier-Brzeska, together with the announcement that he had been killed while serving in the French army.

Between the two issues of Blast, Eliot had arrived in London via Marburg and Oxford, where he had been studying for a degree in philosophy. He met Pound soon after his arrival, and through Pound, Wyndham Lewis. Eliot’s meeting of Pound, who promptly took him under his wing, had two immediate consequences – the publication in Chicago of Prufrock in Harriet Monroe’s Poetry magazine, and the appearance of two other poems a month or two later in Blast. The two issues of Blast established Lewis as a major figure: as a brilliant polemicist and a critic of the basic assumptions and intellectual position of his time, two roles he was never to surrender. Pound had played an important role in Blast, but Lewis was the moving force. Eliot’s role as a contributor of two poems to the second issue was relatively minor, but the enterprise brought them together, and established an association and identified them with a position in the intellectual life of their time which was undoubtedly an important factor in the development and achievement of all three.

Lewis was born in 1882 on a yacht, as was mentioned before, off the coast of Nova Scotia. Pound was born in 1885 in Hailey, Idaho, and Eliot in 1888 in St. Louis. Lewis was brought up in England by his mother, who had separated from his father, was sent to various schools, the last one Rugby, from which he was dropped, spent several years at an art school in London, the Slade, and then went to the continent, spending most of the time in Paris where he studied art, philosophy under Bergson and others, talked, painted and wrote. He returned to England to stay in 1909. It was in the following year that he first met Ezra Pound, in the Vienna Cafe in London. Pound, he wrote many years later, didn’t greatly appeal to him at first – he seemed overly sure of himself and not a little presumptuous. His first impression, he said, was of “a bombastic galleon, palpably bound to or from, the Spanish Main,” but, he discovered, “beneath its skull and cross-bones, intertwined with fleur de lis and spattered with star-spangled oddities, a heart of gold.” As Lewis became better acquainted with Pound he found, as he wrote many years later, that “this theatrical fellow was one of the best.” And he went on to say, “I still regard him as one of the best, even one of the best poets.”

By the time of this meeting, Lewis was making a name for himself, not only as a writer, but also an artist. He had exhibited in London with some success, and shortly before his meeting with Pound, Ford Maddox Ford had accepted a group of stories for publication in the English Review, stories he had written while still in France in which some of the ideas appeared which he was to develop in the more than forty books that were to follow.

But how did Ezra Pound, this young American poet who was born in Hailey, Idaho, and looked, according to Lewis, like an “acclimatized Buffalo Bill,” happen to be in the Vienna Cafe in London in 1910, and what was he doing there? The influence of Idaho, it must be said at once, was slight, since Pound’s family had taken him at an early age to Philadelphia, where his father was employed as an assayer in the U.S. mint. The family lived first in West Philadelphia, then in Jenkintown, and when Ezra was about six bought a comfortable house in Wyncote, where he grew up. He received good training in private schools, and a considerable proficiency in Latin, which enabled him to enter the University of Pennsylvania shortly before reaching the age of sixteen. It was at this time, he was to write some twenty years later, that he made up his mind to become a poet. He decided at that early age that by the time he was thirty he would know more about poetry than any man living. The poetic “impulse”, he said, came from the gods, but technique was man’s responsibility, and he was determined to master it. After two years at Pennsylvania, he transferred to Hamilton, from which he graduated with a Ph.B. two years later. His college years, in spite of his assertions to the contrary, must have been stimulating and developing – he received excellent training in languages, read widely and well, made some friends, including William Carlos Williams, and wrote poetry. After Hamilton he went back to Pennsylvania to do graduate work, where he studied Spanish literature, Old French, Provencal, and Italian. He was granted an M.A. by Pennsylvania in 1906 and a Fellowship in Romantics, which gave him enough money for a summer in Europe, part of which he spent studying in the British museum and part in Spain. The Prado made an especially strong impression on him – thirty years later he could still describe the pictures in the main gallery and recall the exact order in which they were hung. He left the University of Pennsylvania in 1907, gave up the idea of a doctorate, and after one semester teaching at Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana, went to Europe, to return to his native land only for longer or shorter visits, except for the thirteen years he was confined in St. Elizabeth’s in Washington.

Pound’s short stay at Wabash College was something of a disaster – he found Crawfordsville, Indiana, confining and dull, and Crawfordsville, in 1907, found it difficult to adjust itself to a Professor of Romance Languages who wore a black velvet jacket, a soft-collared shirt, flowing bow tie, patent leather pumps, carried a malacca cane, and drank rum in his tea. The crisis came when he allowed a stranded chorus girl he had found in a snow storm to sleep in his room. It was all quite innocent, he insisted, but Wabash didn’t care for his “bohemian ways,” as the President put it, and was glad for the excuse to be rid of him. He wrote some good poetry while at Wabash and made some friends, but was not sorry to leave, and was soon on his way to Europe, arriving in Venice, which he had visited before, with just eighty dollars.

While in Venice he arranged to have a group of his poems printed under the title A Lume Spento. This was in his preparation for his assault on London, since he believed, quite correctly, that a poet would make more of an impression with a printed book of his poetry under his arm than some pages of an unpublished manuscript. He stayed long enough in Venice to recover from the disaster of Wabash and to gather strength and inspiration for the next step, London, where he arrived with nothing more than confidence in himself, three pounds, and the copies of his book of poems. He soon arranged to give a series of lectures at the Polytechnic on the Literature of Southern Europe, which gave him a little money, and to have the Evening Standard review his book of poetry, the review ending with the sentence, “The unseizable magic of poetry is in this queer paper volume, and words are no good in describing it.” He managed to induce Elkin Mathews to publish another small collection, the first printing of which was one hundred copies and soon sold out, then a larger collection, Personae, the Polytechnic engaged him for a more ambitious series of lectures, and he began to meet people in literary circles, including T.E. Hulme, John Butler Yeats, and Ford Maddox Ford, who published his “Ballad of the Goodley Fere” in the English Review. His book on medieval Latin poetry, The Spirit of Romance, which is still in print, was published by Dent in 1910. The Introduction to this book contains the characteristic line, “The history of an art is the history of masterworks, not of failures or of mediocrity.” By the time the first meeting with Wyndham Lewis took place in the Vienna Cafe, then, which was only two years after Pound’s rather inauspicious arrival in London, he was, at the age of 26, known to some as a poet and had become a man of some standing.

It was Pound, the discoverer of talent, the literary impresario, as I have said, who brought Eliot and Lewis together. Eliot’s path to London was as circuitous as Pound’s, but, as one might expect, less dramatic. Instead of Crawfordsville, Indiana, Eliot had spent a year at the Sorbonne after a year of graduate work at Harvard, and was studying philosophy at the University of Marburg with the intention of obtaining a Harvard Ph.D. and becoming a professor, as one of his teachers at Harvard, Josiah Royce, had encouraged him to do, but the war intervened, and he went to Oxford. Conrad Aiken, one of his closest friends at Harvard, had tried earlier, unsuccessfully, to place several of Eliot’s poems with an English publisher, had met Pound, and had given Eliot a latter of introduction to him. The result of that first meeting with Pound are well known – Pound wrote instantly to Harriet Monroe in Chicago, for whose new magazine, Poetry, he had more or less been made European editor, as follows: “An American called Eliot called this P.M. I think he has some sense tho’ he has not yet sent me any verse.” A few weeks later Eliot, while still at Oxford, sent him the manuscript of The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Pound was ecstatic, and immediately transmitted his enthusiasm to Miss Monroe. It was he said, “the best poem I have yet had or seen from an American. Pray God it be not a single and unique success.” Eliot, Pound went on to say, was “the only American I know of who has made an adequate preparation for writing. He has actually trained himself and modernized himself on his own.” Pound sent Prufrock to Miss Monroe in October, 1914, with the words, “The most interesting contribution I’ve had from an American. P.S. Hope you’ll get it in soon.” Miss Monroe had her own ideas – Prufrock was not the sort of poetry she thought young Americans should be writing; she much preferred Vachel Lindsey, whose The Firemen’s Ball she had published in the June issue. Pound, however, was not to be put off; letter followed importuning letter, until she finally surrendered and in the June, 1915, issue of Poetry, now a collector’s item of considerable value, the poem appeared which begins:

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table …

It was not, needless to say, to be the “single and unique success” Pound had feared, but the beginning of one of the great literary careers of this century. The following month the two poems appeared in Blast. Eliot had written little or nothing for almost three years. The warm approval and stimulation of Pound plus, no doubt, the prospect of publication, encouraged him to go on. In October Poetry published three more new poems, and later in the year Pound arranged to have Elkin Matthews, who had published his two books of poetry to bring out a collection which he edited and called The Catholic Anthology which contained the poems that had appeared in Poetry and one of the two from Blast. The principal reason for the whole anthology, Pound remarked, “was to get sixteen pages of Eliot printed in England.”

If all had gone according to plan and his family’s wishes, Eliot would have returned to Harvard, obtained his Ph.D., and become a professor. He did finish his thesis – “To please his parents,” according to his second wife, Valerie Eliot, but dreaded the prospect of a return to Harvard. It didn’t require much encouragement from Pound, therefore, to induce him to stay in England – it was Pound, according to his biographer Noel Stock “who saved Eliot for poetry.” Eliot left Oxford at the end of the term in June, 1915, having in the meantime married Vivien Haigh-Wood. That Fall he took a job as a teacher in a boy’s school at a salary of £140 a year, with dinner. He supplemented his salary by book reviewing and occasional lectures, but it was an unproductive, difficult period for him, his financial problems increased by the illness of his wife. After two years of teaching he took a position in a branch of Lloyd’s bank in London, hoping that this would give him sufficient income to live on, some leisure for poetry, and a pension for his wife should she outlive him. Pound at this period fared better than Eliot – he wrote music criticism for a magazine, had some income from other writing and editorial projects, which was supplemented by the small income of his wife, Dorothy Shakespear and occasional checks from his father. He also enjoyed a more robust constitution that Eliot, who eventually broke down under the strain and was forced, in 1921, to take a rest cure in Switzerland. It was during this three-month stay in Switzerland that he finished the first draft of The Waste Land, which he immediately brought to Pound. Two years before, Pound had taken Eliot on a walking tour in France to restore his health, and besides getting Eliot published, was trying to raise a fund to give him a regular source of income, a project he called “Bel Esprit.” In a latter to John Quinn, the New York lawyer who used his money, perceptive critical judgment and influence to help writers and artists, Pound, referring to Eliot, wrote, “It is a crime against literature to let him waste eight hours vitality per diem in that bank.” Quinn agreed to subscribe to the fund, but it became a source of embarrassment to Eliot who put a stop to it.

The Waste Land marked the high point of Eliot’s literary collaboration with Pound. By the time Eliot had brought him the first draft of the poem, Pound was living in Paris, having left London, he said, because “the decay of the British Empire was too depressing a spectacle to witness at close range.” Pound made numerous suggestions for changes, consisting largely of cuts and rearrangements. In a latter to Eliot explaining one deletion he wrote, “That is 19 pages, and let us say the longest poem in the English langwidge. Don’t try to bust all records by prolonging it three pages further.” A recent critic described the processes as one of pulling “a masterpiece out of a grabbag of brilliant material”; Pound himself described his participation as a “Caesarian operation.” However described, Eliot was profoundly grateful, and made no secret of Pound’s help. In his characteristically generous way, Eliot gave the original manuscript to Quinn, both as a token for the encouragement Quinn had given to him, and for the further reason, as he put it in a letter to Quinn, “that this manuscript is worth preserving in its present form solely for the reason that it is the only evidence of the difference which his [Pound’s] criticism has made to the poem.” For years the manuscript was thought to have been lost, but it was recently found among Quinn’s papers which the New York Public Library acquired some years after his death, and now available in a facsimile edition.

The first publication of The Waste Land was in the first issue of Eliot’s magazine Criterion, October, 1922. The following month it appeared in New York in The Dial. Quinn arranged for its publication in book form by Boni and Liveright, who brought it out in November. The first printing of one thousand was soon sold out, and Eliot was given the Dial award of the two thousand dollars. Many were puzzled by The Waste Land, one reviewer even thought that Mr. Eliot might be putting over a hoax, but Pound was not alone in recognizing that in his ability to capture the essence of the human condition in the circumstances of the time, Eliot had shown himself, in The Waste Land, to be a poet. To say that the poem is merely a reflection of Eliot’s unhappy first marriage, his financial worries and nervous breakdown is far too superficial. The poem is a reflection, not of Eliot, but of the aimlessness, disjointedness, sordidness of contemporary life. In itself, it is in no way sick or decadent; it is a wonderfully evocative picture of the situation of man in the world as it is. Another poet, Kathleen Raine, writing many years after the first publication of The Waste Land on the meaning of Eliot’s early poetry to her generation, said it

…enabled us to know our generation imaginatively. All those who have lived in the Waste Land of London can, I suppose, remember the particular occasion on which, reading T.S. Eliot’s poems for the first time, an experience of the contemporary world that had been nameless and formless received its apotheosis.

Eliot sent one of the first copies he received of the Boni and Liveright edition to Ezra Pound with the inscription “for E.P. miglior fabbro from T.S.E. Jan. 1923.” His first volume of collected poetry was dedicated to Pound with the same inscription, which came from Dante and means, “the better marker.” Explaining this dedication Eliot wrote in 1938:

I wished at that moment to honour the technical mastery and critical ability manifest in [Pound’s] . . . work, which had also done so much to turn The Waste Land from a jumble of good and bad passages into a poem.

Pound and Eliot remained in touch with each other – Pound contributed frequently to the Criterion, and Eliot, through his position at Faber and Faber, saw many of Pounds’ books through publication and himself selected and edited a collection of Pound’s poetry, but there was never again that close collaboration which had characterized their association from their first meeting in London in 1914 to the publication of The Waste Land in the form given it by Pound in 1922.

As has already been mentioned, Pound left London in 1920 to go to Paris, where he stayed on until about 1924 – long enough for him to meet many people and for the force of his personality to make itself felt. He and his wife were frequent visitors to the famous bookshop, Shakespeare and Co. run by the young American Sylvia Beach, where Pound, among other things, made shelves, mended chairs, etc.; he also was active gathering subscriptions for James Joyces’ Ulysses when Miss Beach took over its publication. The following description by Wyndham Lewis of an encounter with Pound during the latter’s Paris days is worth repeating. Getting no answer after ringing the bell of Pound’s flat, Lewis walked in and discovered the following scene:

A splendidly built young man, stripped to the waist, and with a torso of dazzling white, was standing not far from me. He was tall, handsome and serene, and was repelling with his boxing gloves – I thought without undue exertion – a hectic assault of Ezra’s. After a final swing at the dazzling solar plexus (parried effortlessly by the trousered statue) Pound fell back upon the settee. The young man was Hemingway.

Pound, as is well known, took Hemingway in hand, went over his manuscripts, cut out superfluous words as was custom, and helped him find a publisher, a service he had performed while still in London for another young American, Robert Frost. In a letter to Pound, written in 1933, Hemingway acknowledged the help Pound had given him by saying that he had learned more about “how to write and how not to write” from him “than from any son of a bitch alive, and he always said so.”

When we last saw Lewis, except for his brief encounter with Pound and Hemingway wearing boxing gloves, he had just brought out the second issues of Blast and gone off to the war to end all war. He served for a time at the front in an artillery unit, and was then transferred to a group of artists who were supposed to devote their time to painting and drawing “the scene of war,” as Lewis put it, a scheme which had been devised by Lord Beaverbrook, through whose intervention Lewis received the assignment. He hurriedly finished a novel, Tarr, which was published during the war, largely as a result of Pound’s intervention, in Harriet Shaw Weaver’s magazine The Egoist, and in book form after the war had ended. It attracted wide attention; Rebecca West, for example, called it “A beautiful and serious work of art that reminds one of Dostoevsky.” By the early twenties, Lewis, as the editor of Blast, the author of Tarr and a recognized artist was an established personality, but he was not then, and never became a part of the literary and artistic establishment, nor did he wish to be.

For the first four years following his return from the war and recovery from a serious illness that followed it little was heard from Lewis. He did bring out two issues of a new magazine, The Tyro, which contained contributions from T.S. Eliot, Herbert Read and himself, and contributed occasionally to the Criterion, but it was a period, for him, of semi-retirement from the scene of battle, which he devoted to perfecting his style as a painter and to study. It was followed by a torrent of creative activity – two important books on politics, The Art of Being Ruled (1926) and The Lion and the Fox (1927), a major philosophical work, Time and Western Man (1927), followed by a collection of stories, The Wild Body (1927) and the first part of a long novel, Childermass (1928). In 1928, he brought out a completely revised edition of his wartime novel Tarr, and if all this were not enough, he contributed occasionally to the Criterion, engaged in numerous controversies, painted and drew. In 1927 he founded another magazine, The Enemy, of which only three issues appeared, the last in 1929. Lewis, of course, was “the Enemy.” He wrote in the first issue:

The names we remember in European literature are those of men who satirised and attacked, rather than petted and fawned upon, their contemporaries. Only this time exacts an uncritical hypnotic sleep of all within it.

One of Lewis’ best and most characteristic books is Time and Western Man; it is in this book that he declared war, so to speak, on what he considered the dominant intellectual position of the twentieth century – the philosophy of time, the school of philosophy, as he described it, for which “time and change are the ultimate realities.” It is the position which regards everything as relative, all reality a function of time. “The Darwinian theory and all the background of nineteenth century thought was already behind it,” Lewis wrote, and further “scientific” confirmation was provided by Einstein’s theory of relativity. It is a position, in Lewis’ opinion, which is essentially romantic, “with all that word conveys in its most florid, unreal, inflated, self-deceiving connotation.”

The ultimate consequence of the time philosophy, Lewis argued, is the degradation of man. With its emphasis on change, man, the man of the present, living man for the philosophy of time ends up as little more than a minute link in the endless process of progressive evolution –lies not in what he is, but in what he as a species, not an individual, may become. As Lewis put it:

You, in imagination, are already cancelled by those who will perfect you in the mechanical time-scale that stretches out, always ascending, before us. What do you do and how you live has no worth in itself. You are an inferior, fatally, to all the future.

Against this rather depressing point of view, which deprives man of all individual worth, Lewis offers the sense of personality, “the most vivid and fundamental sense we possess,” as he describes it. It is this sense that makes man unique; it alone makes creative achievement possible. But the sense of personality, Lewis points out, is essentially one of separation, and to maintain such separation from others requires, he believes, a personal God. As he expressed it: “In our approaches to God, in consequence, we do not need to “magnify” a human body, but only to intensify that consciousness of a separated and transcendent life. So God becomes the supreme symbol of our separation and our limited transcendence….It is, then, because the sense of personality is posited as our greatest “real”, that we require a “God”, a something that is nothing but a person, secure in its absolute egoism, to be the rationale of this sense.”

It is exactly “our separation and our limited transcendence” that the time philosophy denies us; its God is not, in Lewis’ words “a perfection already existing, eternally there, of which we are humble shadows,” but a constantly emerging God, the perfection toward which man is thought to be constantly striving. Appealing as such a conception may on its surface appear to be, this God we supposedly attain by our strenuous efforts turns out to be a mocking God; “brought out into the daylight,” Lewis said, “it would no longer be anything more than a somewhat less idiotic you.”

In Time and Western Man Lewis publicly disassociated himself from Pound, Lewis having gained the erroneous impression, apparently, that Pound had become involved in a literary project of some kind with Gertrude Stein, whom Lewis hated with all the considerable passion of which he was capable. To Lewis, Gertrude Stein, with her “stuttering style” as he called it, was the epitomy of “time philosophy” in action. The following is quoted by Lewis is in another of his books, The Diabolical Principle, and comes from a magazine published in Paris in 1925 by the group around Gertrude Stein; it is quoted here to give the reader some idea of the reasons for Lewis’ strong feelings on the subject of Miss Stein:

If we have a warm feeling for both (the Superrealists) and the Communists, it is because the movements which they represent are aimed at the destruction of a thoroughly rotten structure … We are entertained intellectually, if not physically, with the idea of (the) destruction (of contemporary society). But … our interests are confined to literature and life … It is our purpose purely and simply to amuse ourselves.

The thought that Pound would have associated himself with a group expounding ideas on this level of irresponsibility would be enough to cause Lewis to write him off forever, but it wasn’t true; Pound had met Gertrude Stein once or twice during his stay in Paris, but didn’t get on with her, which isn’t at all surprising. Pound also didn’t particularly like Paris, and in 1924 moved to Rapallo, a small town on the Mediterranean a few miles south of Genoa, where he lived until his arrest by the American authorities at the end of World War II.

In an essay written for Eliot’s sixtieth birthday, Lewis had the following to say about the relationship between Pound and Eliot:

It is not secret that Ezra Pound exercised a very powerful influence upon Mr. Eliot. I do not have to define the nature of this influence, of course. Mr. Eliot was lifted out of his lunar alley-ways and fin de siecle nocturnes, into a massive region of verbal creation in contact with that astonishing didactic intelligence, that is all.

Lewis’ own relationship with Pound was of quite a different sort, but during the period from about 1910 to 1920, when Pound left London, was close, friendly, and doubtless stimulating to both. During Lewis’ service in the army, Pound looked after Lewis’ interests, arranged for the publication of his articles, tried to sell his drawings, they even collaborated in a series of essays, written in the form of letters, but Lewis, who in any case was inordinately suspicious, was quick to resent Pound’s propensity to literary management. After Pound settled in Rapallo they corresponded only occasionally, but in 1938, when Pound was in London, Lewis made a fine portrait of him, which hangs in the Tate Gallery. In spite of their occasional differences and the rather sharp attack on Pound in Time and Western Man, they remained friends, and Lewis’ essay for Eliot’s sixtieth birthday, which was written while Pound was still confined in St. Elizabeth’s, is devoted largely to Pound, to whom Lewis pays the following tribute:

So, for all his queerness at times–ham publicity of self, misreading of part of poet in society–in spite of anything that may be said Ezra is not only himself a great poet, but has been of the most amazing use to other people. Let it not be forgotten for instance that it was he who was responsible for the all-important contact for James Joyce–namely Miss Weaver. It was his critical understanding, his generosity, involved in the detection and appreciation of the literary genius of James Joyce. It was through him that a very considerable sum of money was put at Joyce’s disposal at the critical moment.

Lewis concludes his comments on Pound with the following:

He was a man of letters, in the marrow of his bones and down to the red rooted follicles of his hair. He breathed Letters, ate Letters, dreamt Letters. A very rare kind of man.

Two other encounters during his London period had a lasting influence on Pound’s thought and career–the Oriental scholar Ernest Fenollosa and Major Douglas, the founder of Social Credit. Pound met Douglas in 1918 in the office of The New Age, a magazine edited by Alfred H. Orage, and became an almost instant convert. From that point on usury became an obsession with him, and the word “usurocracy,” which he used to denote a social system based on money and credit, an indispensable part of his vocabulary. Social Credit was doubtless not the panacea Pound considered it to be, but that Major Douglas was entirely a fool seems doubtful too, if the following quotation from him is indicative of the quality of his thought:

I would .. make the suggestion … that the first requisite of a satisfactory governmental system is that it shall divest itself of the idea that it has a mission to improve the morals or direct the philosophy of any of its constituent citizens.

Ernest Fenollosa was a distinguished Oriental scholar of American origin who had spent many years in Japan, studying both Japanese and Chinese literature, and had died in 1908. Pound met his widow in London in 1913, with the result that she entrusted her husband’s papers to him, with her authorization to edit and publish them as he thought best. Pound threw himself into the study of the Fenollosa material with his usual energy, becoming, as a result, an authority on the Japanese Noh drama and a lifelong student of Chinese. He came to feel that the Chinese ideogram, because it was never entirely removed from its origin in the concrete, had certain advantages over the Western alphabet. Two years after receiving the Fenollosa manuscripts, Pound published a translation of Chinese poetry under the title Cathay. The Times Literary Supplement spoke of the language of Pound’s translation as “simple, sharp, precise.” Ford Maddox Ford, in a moment of enthusiasm, called Cathay “the most beautiful book in the language.”

Pound made other translations, from Provencal, Italian, Greek, and besides the book of Chinese poetry, translated Confucius, from which the following is a striking example, and represents a conception of the relationship between the individual and society to which Pound attached great importance, and frequently referred to in his other writing:

The men of old wanting to clarify and diffuse throughout the empire that light which comes from looking straight into the heart and then acting, first set up good government in their own states; wanting good government in their states, they first established order in their own families; wanting order in the home, they first disciplined themselves; desiring self-discipline, they rectified their own hearts; and wanting to rectify their hearts; they sought precise verbal definitions of their inarticulate thoughts; wishing to attain precise verbal definitions, they sought to extend their knowledge to the utmost. This completion of knowledge is rooted in sorting things into organic categories.

When things had been classified in organic categories, knowledge moved toward fulfillment; given the extreme knowable points, the inarticulate thoughts were defined with precision. Having attained this precise verbal definition, they then stabilized their hearts, they disciplined themselves; having attained self-discipline, they set their own houses in order; having order in their own homes, they brought good government to their own states; and when their states were well governed, the empire was brought into equilibrium.

Pound’s major poetic work is, of course, The Cantos, which he worked on over a period of more than thirty years. One section, The Pisan Cantos, comprising 120 pages and eleven cantos, was written while Pound was confined in a U.S. Army detention camp near Pisa, for part of the time in a cage. Pound’s biographer, Noel Stock, himself a poet and a competent critic, speaks of the Pisan Cantos as follows:

They are confused and often fragmentary; and they bear no relation structurally to the seventy earlier cantos; but shot through by a rare sad light they tell of things gone which somehow seem to live on, and are probably his best poetry. In those few desperate months he was forced to return to that point within himself where the human person meets the outside world of real things, and to speak of what he found there. If at times the verse is silly, it is because in himself Pound was often silly; if at times it is firm, dignified and intelligent, it is because in himself Pound was often firm, dignified and intelligent; if it is fragmentary and confused, it is because Pound was never able to think out his position and did not know how the matters with which he dealt were related; and if often lines and passages have a beauty seldom equaled in the poetry of the twentieth century it is because Pound had a true lyric gift.

As for the Cantos as a whole, I am not competent to make even a comment, much less to pass judgment. Instead I will quote the distinguished English critic Sir Herbert Read on the subject:

I am not going to deny that for the most part the Cantos present insuperable difficulties for the impatient reader, but, as Pound says somewhere, “You can’t get through hell in a hurry.” They are of varying length, but they already amount to more than five hundred pages of verse and constitute the longest, and without hesitation I would say the greatest, poetic achievement of our time.