Right-wing critics of Christianity often quote from The Hour of Decision, the last work of a once widely read German historian of philosophy, Oswald Spengler. This short, graphically composed book was published in 1933, the year Adolf Hitler took power in Germany. Although it has never been proven, there is a suspicion that the Nazi government disposed of this onetime hero of the right, who did not hide his contempt for Hitler or his “plebeian” followers. Spengler supposedly referred to Christianity as the “Bolshevism of antiquity,” and today’s neo-pagan Alt-Right has picked up his description to justify its contempt for Christianity as a proto-socialist religion of slaves.

Having found the original statement in the German text, which I own, I am not sure the Alt-Right has interpreted Spengler’s drift correctly. The author is not expressing contempt for the primitive church but rather viewing it as a prototype for revolutionary movements. Spengler correctly suggests that Marx, Engels, and the Bolsheviks, despite their pretension to being “scientific socialists,” viewed the early church as a model for their own movement; as did the French anarchist Georges Sorel, who thought his labor-class revolutionary movement needed a “redemptive myth” as powerful as the one that animated early Christians.

Having found the original statement in the German text, which I own, I am not sure the Alt-Right has interpreted Spengler’s drift correctly. The author is not expressing contempt for the primitive church but rather viewing it as a prototype for revolutionary movements. Spengler correctly suggests that Marx, Engels, and the Bolsheviks, despite their pretension to being “scientific socialists,” viewed the early church as a model for their own movement; as did the French anarchist Georges Sorel, who thought his labor-class revolutionary movement needed a “redemptive myth” as powerful as the one that animated early Christians.

In Christianity, Spengler and Sorel saw a religion of the downtrodden—though they may have exaggerated the predominance of slaves and the poor in early Christianity—one which practiced communal ownership as it awaited the end of human history. Moreover, after an initial persecution and the killing of martyrs, this religious community managed to become the official religion of the Roman Empire. All other revolutionaries on the left, as opposed to revolutionary nationalists on the right (who were heavily influenced by neo-paganism), found lessons in the ascent of the early church from its humble beginnings.

Christians themselves later looked back at how their church rose from these blood-stained, painful beginnings to become a dominant world religion. They ascribed this course of events to divine Providence. Sometimes, as in the writings of St. Augustine, the trials would have to be endured by the faithful until the end of secular history. But there was an upward course in which the founding of the church presaged the end times, when Christ would return.

The centrality of this founding and its institutional arrangements played an even larger role for radical Protestants. Sects like the German Anabaptists in the 16th century and the Fifth Monarchy Men during the English Civil War in the 17th century believed they were living in a final historical age and that their attempted return to the primitive church was being undertaken in preparation for Christ’s Second Coming. Among such sectarians, of whom there were many in early modern Europe, going back to the early church was essential to their plans.

Indeed, much of the Protestant Reformation was about returning to a purer form of Christianity before papal councils and institutions borrowed from the pagan world were thought to have corrupted the true faith. Significantly for Luther and other earlier Reformers, the “fall of the church” was not seen to have occurred in the early centuries. This fall was mostly identified with the High Middle Ages and papal monarchical pretensions. But for the more radical Anabaptists, Christendom had already fallen into grievous error when the church leaders gave power over its deliberations and decisions to Roman emperors. The early church had remained uncorrupted because it was separated from political power.

A different model, however, became prevalent in Puritanism, especially after this religious movement traveled to the New World. Perry Miller’s classic study Errand into the Wilderness (1956), leaves no doubt about the overshadowing presence of the ancient Hebrews on Puritan society and religion. The New Israelites—which is how the Puritans envisioned themselves—were bound by a covenant, just as the ancient Jews had been under the covenant of Abraham and Moses. Just as the Hebrews had gone forth from bondage to settle the Holy Land, so too were their Puritan successors summoned into the North American wilderness to carry out a divine mandate. They were to establish their own community of believers where they would build the godly city on the hill as the New Jerusalem. Puritan sermons and political ordinances are so permeated with Hebrew and Old Testament images and phrases that their borrowings from an earlier chosen people are unmistakable. Harvard, Yale, and other originally Puritan institutions encouraged the study of biblical Hebrew, and the most common Christian names given to both sexes were taken from Hebrew Scripture.

A different model, however, became prevalent in Puritanism, especially after this religious movement traveled to the New World. Perry Miller’s classic study Errand into the Wilderness (1956), leaves no doubt about the overshadowing presence of the ancient Hebrews on Puritan society and religion. The New Israelites—which is how the Puritans envisioned themselves—were bound by a covenant, just as the ancient Jews had been under the covenant of Abraham and Moses. Just as the Hebrews had gone forth from bondage to settle the Holy Land, so too were their Puritan successors summoned into the North American wilderness to carry out a divine mandate. They were to establish their own community of believers where they would build the godly city on the hill as the New Jerusalem. Puritan sermons and political ordinances are so permeated with Hebrew and Old Testament images and phrases that their borrowings from an earlier chosen people are unmistakable. Harvard, Yale, and other originally Puritan institutions encouraged the study of biblical Hebrew, and the most common Christian names given to both sexes were taken from Hebrew Scripture.

In considering why these early American settlers were so mesmerized by the example of the ancient Hebrews, we might look at the European Calvinists from whom they were theologically descended. Like the American Puritans, Protestant followers of John Calvin strongly rejected the tradition of Roman authority they found in the Catholic Church. For them, the Catholics were too heavily influenced in their authority structure and canon law by Roman paganism. The early Protestants felt it necessary to return to the Bible as a guide for building a Christian society.

Calvinists also believed that salvation came through unmerited divine election. Since all humans had fallen away from God with the sin of Adam, no mortal could earn grace through his own efforts. Indeed, any sense that humans earned grace was mere vanity on our parts, for outside of God’s will, which was inscrutable to man, there could be no salvation. Yet those who were elected had a sense of being saved and lived in a manner that comported with the undeserved grace that had been ascribed to them by an all-knowing and all-powerful Deity.

Particularly revealing for the Calvinists in general were the passages in Deuteronomy, in which the Israelites are shown two paths, either obedience to divine commandments, which will result in blessings for the people, or falling away, which will bring collective curses. In this narrative, the Puritans and other Calvinists saw the paths that were laid out for their own lives. If they grasped the signs of divine election and acted accordingly, they would prosper; if they were among the sinners, they would suffer in this life and in the next.

Like their ancient model, the Calvinists strongly focused on signs of divine favor or divine disfavor in this life. Preparing for the next life was not a particularly rewarding task for those who never knew for sure whether they belonged “in that number when the saints go marching in.” No matter how hard the Puritans tried to believe they were in “that number,” some doubt probably lingered in their minds. That black spiritual about the saints marching in, which first began to be sung about a hundred years ago, refers to the end times, not to the afterlife.

Millenarianism, which refers to a preoccupation with the thousand-year kingdom that would usher in Christ’s rule, became a recognizable part of American Protestant culture. Although tonier Calvinist denominations, like Congregationalists and Presbyterians, moved away from such speculative points, less upper-class denominations like Southern Baptists absorbed them. Such speculation about the end times drew from the Hebrew prophets and the Book of Daniel, as well as from the Book of Revelation in the New Testament. It also became strongly associated with an American brand of Protestantism. It was one in which fevered debates took place between Pre- and Post-Millenarians, those who believed that Christ would return before the end of secular history and those who believed that humanity would first have to endure “the tribulations” before Christ returned.

A Calvinist legacy, with a strong Old Testament orientation, and various forms of millenarianism shaped American culture and politics. A once-deeply-embedded Protestant work ethic, which originated in Calvinist moral theology; an emphasis on public morality, the content of which went back to the Mosaic law; and a view of religion as above all an individual commitment, have roots in America’s Calvinist founding. The willingness to tolerate religious dissenters, which by the late 18th century had become a more-or-less prevalent American view, also went back to the Protestant idea that religion depended on the individual’s experience of faith, independent of priestly mediation or hierarchical structures.

Finally, republican government fit with the Calvinist-Puritan historical experience. In Europe, Catholic and High Church Anglican monarchs had opposed the proliferation of Protestant sects and had often been at war with the Calvinists. When James I tried to unite the Anglican and Presbyterian confessions in the late 16th century, the deal breaker was the Scottish Calvinist refusal to accept the office of bishop. To which James famously and presciently responded, “No bishop, no king.” The political and ecclesiastical chain of command understandably went together in the king’s mind.

These Protestant traditions have served the American people well. Religious freedom but not indifferentism, the enforcement of strong communal moral standards, and the expectation that the young will apply themselves diligently to their work and study as a religious act, have all benefited our country. So have the Calvinist Protestant suspicion of power in the hands of earthly princes and an awareness of the need to rein in such political actors. One need not denigrate other political or religious traditions that suit other societies to recognize the strengths of what has worked well in this country. It is also the case that the Puritan-Calvinist value of teaching the young to study biblical and classical languages was a spur to education and the founding of great universities in early America.

These Protestant traditions have served the American people well. Religious freedom but not indifferentism, the enforcement of strong communal moral standards, and the expectation that the young will apply themselves diligently to their work and study as a religious act, have all benefited our country. So have the Calvinist Protestant suspicion of power in the hands of earthly princes and an awareness of the need to rein in such political actors. One need not denigrate other political or religious traditions that suit other societies to recognize the strengths of what has worked well in this country. It is also the case that the Puritan-Calvinist value of teaching the young to study biblical and classical languages was a spur to education and the founding of great universities in early America.

Still, the Protestant legacy has had its problematic side, much of which is related to the idea of divine election. At least in American politics, it has expressed itself in a moral arrogance that has nurtured a missionary foreign policy from which our country cannot seem to break free. Martin E. Marty, a Lutheran scholar, entitled his history of American Protestantism Righteous Empire (1970). The American government’s relation with other countries has usually meant trying to export our “democratic values” and “human rights” while making others more like ourselves. That means stressing whatever our dominant values are at any given time, be it traditional Judeo-Christian morality or LGBT self-expression. But whatever those rights and values are, they are supposedly universally valid because they come from an “exceptional nation” (read: Calvin’s ingathering of the elect); and it has been America’s destiny to become “a city on a hill,” albeit not in the manner intended by Governor Winthrop of Massachusetts who constructed that phrase in the 17th century. We end wars against the wicked with demands for unconditional surrender and then we hold war trials so that our virtues can stand out more brightly in relation to those reprobates whom we have just defeated.

Calvinist scholar James Kurth (photo) once defined “the American Creed” that dominated American views of international relations in the 20th century as a degraded form of American Protestant theology:

Calvinist scholar James Kurth (photo) once defined “the American Creed” that dominated American views of international relations in the 20th century as a degraded form of American Protestant theology:

The elements of the American Creed were free markets and equal opportunity, free elections and liberal democracy, and constitutionalism and the rule of law. The American Creed definitely did not include as elements hierarchy, community, tradition, and custom. Although the American Creed was not itself Protestant, it was clearly the product of a Protestant culture—a sort of secularized version of Protestantism…

Although Kurth views this American missionary politics as peculiarly American and as a “declension of the Reformation,” he also stresses its rootedness in the individualism and repugnance for hierarchy that came out of older Protestant thinking. This creed is intolerant of societies and countries that display traditional ways of life. It requires redeemed Americans to raise the less fortunate or perverse out of their degraded conditions. According to Kurth, one has yet to figure out how to keep the Protestant baby while disposing of the unwanted bathwater. But as the American Creed has become more widespread, much of its original Protestant character has eroded. Today, Protestants are far from the only ones boasting about American exceptionalism and an American mission.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Front Populaire :

Front Populaire :

PG : De mon point de vue, la grille de lecture droite/gauche est encore plus problématique aux États-Unis qu’elle ne l’est en France comme l’a démontré mon ami Arnaud Imatz, notamment dans son ouvrage Droite-Gauche, pour sortir de l’équivoque. Je pense que le clivage le plus structurant de la vie politique américaine s’articule aujourd’hui dans l’opposition entre les partisans de l’« America First » (ndlr : littéralement, L’Amérique d’abord, soit une politique fondée sur la primauté des intérêts intérieurs américains) contre ceux qui entendent que l’Amérique domine le monde (y compris, selon eux, pour le bien de celui-ci) en s’engageant un peu partout sur la planète. Cela explique le regard noir porté sur la politique protectionniste du président sortant.

PG : De mon point de vue, la grille de lecture droite/gauche est encore plus problématique aux États-Unis qu’elle ne l’est en France comme l’a démontré mon ami Arnaud Imatz, notamment dans son ouvrage Droite-Gauche, pour sortir de l’équivoque. Je pense que le clivage le plus structurant de la vie politique américaine s’articule aujourd’hui dans l’opposition entre les partisans de l’« America First » (ndlr : littéralement, L’Amérique d’abord, soit une politique fondée sur la primauté des intérêts intérieurs américains) contre ceux qui entendent que l’Amérique domine le monde (y compris, selon eux, pour le bien de celui-ci) en s’engageant un peu partout sur la planète. Cela explique le regard noir porté sur la politique protectionniste du président sortant.

It may be Nock’s “

It may be Nock’s “

Gumplowicz nennt für den Aufbau des Staates eine Reihe von Folgeerscheinungen. Dabei verschwand die Rassentrennung nicht ganz. Vielmehr wird sie in die staatliche Ordnung eingebettet und tritt als eine staatlich gewährleistete Rangfolge auf. Gumplowicz erklärt: „Denn schließlich ist Herrschaft nichts anderes als eine durch Übermacht geregelte Teilung der Arbeit, bei der den Beherrschten die niedrigeren und schweren, den Herrschenden die höheren und leichteren (oft nur das Befehlen und Verwalten) zufällt. Wie aber ohne Teilung der Arbeit keinerlei Kultur denkbar ist, so ist ohne Herrschaft keine gedeihliche Teilung der Arbeit möglich, weil sich, wie gesagt, freiwillig niemand zur Leistung der niedrigeren und schwereren Arbeit hergeben wird.“ Dieser Punkt ist wichtig: Obwohl die „Vergesellschaftung der Sprache und Religion“ zu einer „amalgamierten“ Gesellschaft führt, wirkt die Staatenbildung gleichzeitig darauf hin, eine Herrschaftsordnung mit einer Trennung von Herrschern und Beherrschten zu festigen.

Gumplowicz nennt für den Aufbau des Staates eine Reihe von Folgeerscheinungen. Dabei verschwand die Rassentrennung nicht ganz. Vielmehr wird sie in die staatliche Ordnung eingebettet und tritt als eine staatlich gewährleistete Rangfolge auf. Gumplowicz erklärt: „Denn schließlich ist Herrschaft nichts anderes als eine durch Übermacht geregelte Teilung der Arbeit, bei der den Beherrschten die niedrigeren und schweren, den Herrschenden die höheren und leichteren (oft nur das Befehlen und Verwalten) zufällt. Wie aber ohne Teilung der Arbeit keinerlei Kultur denkbar ist, so ist ohne Herrschaft keine gedeihliche Teilung der Arbeit möglich, weil sich, wie gesagt, freiwillig niemand zur Leistung der niedrigeren und schwereren Arbeit hergeben wird.“ Dieser Punkt ist wichtig: Obwohl die „Vergesellschaftung der Sprache und Religion“ zu einer „amalgamierten“ Gesellschaft führt, wirkt die Staatenbildung gleichzeitig darauf hin, eine Herrschaftsordnung mit einer Trennung von Herrschern und Beherrschten zu festigen. Gumplowicz bringt seine brutalen Grundsätze aber nicht vor, um Blutvergießen zu rechtfertigen oder die Herrschenden zum Krieg aufzustacheln. Ihm geht es darum, auf die blutige Voraussetzung jeder Staatswerdung aufmerksam zu machen. Er distanziert sich von der Gefühlsduselei, die schon zu seiner Zeit die Darstellungen der internationalen Beziehungen prägten. Und nicht zuletzt versucht er, menschliche Erfahrungen und Errungenschaften ohne die übliche Weichzeichnung darzustellen. Die Wechselwirkung von Rassenstreitigkeiten und dem nachfolgenden Amalgamierungsdrang stellt Gumplowicz nochmals in „Rasse und Staat. Eine Untersuchung über das Gesetz der Staatenbildung“ (1875) dar: „Ohne Rassengegensätze gibt es keinen Staat und keine staatliche Entwicklung, und ohne Rassenverschmelzung gibt es keine Kultur und keine Zivilisation.“

Gumplowicz bringt seine brutalen Grundsätze aber nicht vor, um Blutvergießen zu rechtfertigen oder die Herrschenden zum Krieg aufzustacheln. Ihm geht es darum, auf die blutige Voraussetzung jeder Staatswerdung aufmerksam zu machen. Er distanziert sich von der Gefühlsduselei, die schon zu seiner Zeit die Darstellungen der internationalen Beziehungen prägten. Und nicht zuletzt versucht er, menschliche Erfahrungen und Errungenschaften ohne die übliche Weichzeichnung darzustellen. Die Wechselwirkung von Rassenstreitigkeiten und dem nachfolgenden Amalgamierungsdrang stellt Gumplowicz nochmals in „Rasse und Staat. Eine Untersuchung über das Gesetz der Staatenbildung“ (1875) dar: „Ohne Rassengegensätze gibt es keinen Staat und keine staatliche Entwicklung, und ohne Rassenverschmelzung gibt es keine Kultur und keine Zivilisation.“

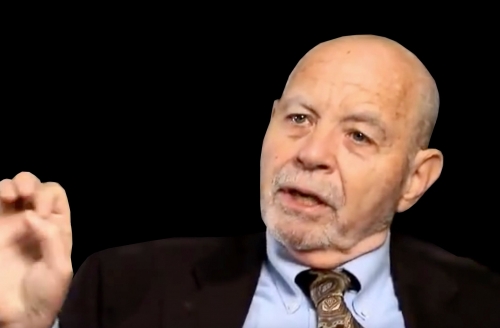

Multiculturalism and the Politics of Guilt extends Paul Gottfried’s examination of Western managerial government’s growth in the last third of the twentieth century. Linking multiculturalism to a distinctive political and religious context, the book argues that welfare-state democracy, unlike bourgeois liberalism, has rejected the once conventional distinction between government and civil society. Gottfried argues that the West’s relentless celebrations of diversity have resulted in the downgrading of the once dominant Western culture. The moral rationale of government has become the consciousness-raising of a presumed majority population. While welfare states continue to provide entitlements and fulfill the other material programs of older welfare regimes, they have ceased to make qualitative leaps in the direction of social democracy. For the new political elite, nationalization and income redistributions have become less significant than controlling the speech and thought of democratic citizens. An escalating hostility toward the bourgeois Christian past, explicit or at least implicit in the policies undertaken by the West and urged by the media, is characteristic of what Gottfried labels an emerging “therapeutic” state. For Gottfried, acceptance of an intrusive political correctness has transformed the religious consciousness of Western, particularly Protestant, society. The casting of “true” Christianity as a religion of sensitivity only toward victims has created a precondition for extensive social engineering.

Multiculturalism and the Politics of Guilt extends Paul Gottfried’s examination of Western managerial government’s growth in the last third of the twentieth century. Linking multiculturalism to a distinctive political and religious context, the book argues that welfare-state democracy, unlike bourgeois liberalism, has rejected the once conventional distinction between government and civil society. Gottfried argues that the West’s relentless celebrations of diversity have resulted in the downgrading of the once dominant Western culture. The moral rationale of government has become the consciousness-raising of a presumed majority population. While welfare states continue to provide entitlements and fulfill the other material programs of older welfare regimes, they have ceased to make qualitative leaps in the direction of social democracy. For the new political elite, nationalization and income redistributions have become less significant than controlling the speech and thought of democratic citizens. An escalating hostility toward the bourgeois Christian past, explicit or at least implicit in the policies undertaken by the West and urged by the media, is characteristic of what Gottfried labels an emerging “therapeutic” state. For Gottfried, acceptance of an intrusive political correctness has transformed the religious consciousness of Western, particularly Protestant, society. The casting of “true” Christianity as a religion of sensitivity only toward victims has created a precondition for extensive social engineering.

For full disclosure, let me mention that at least one of Scott’s French contacts, Arnaud Imatz, who represents perfectly the kind of French intellectual he describes, is someone whom the author met through me. Arnaud and I have been friends and correspondents for over 30 years, and his understanding of the French nation and the enjeu social (social question) confronting his people make eminently good sense to Scott and me. Although I have focused on German more than French intellectual history, most of the authors and social critics whom Scott cites are for me familiar names. I agree with Scott that Éric Zemmour, a Moroccan Jew who has tried to revive the sense of French honor that he associates with the late General de Gaulle, illustrates the new identitarian French politics. So too does the iconoclastic novelist Michel Houellebecq, who, despite his shockingly erotic work, clearly loathes multiculturalism and despises French Islamophiles. Another figure in this Pleiades of intellectuals of the French right is Christophe Guilluy, who often sounds like the French Steve Bannon. In his books La France périphérique(2014) and Le crepuscule de la France d’en haut (2016), Guilluy comes to the defense of that 60 percent of the French population living on the “periphery,” that is, outside of metropolitan areas and the sprawling suburbs. These are the “les Francais de souche,” the true indigenous French, whom the globalist elites treat like human waste while they cut production costs by bringing in cheap labor from the Muslim Third World.

For full disclosure, let me mention that at least one of Scott’s French contacts, Arnaud Imatz, who represents perfectly the kind of French intellectual he describes, is someone whom the author met through me. Arnaud and I have been friends and correspondents for over 30 years, and his understanding of the French nation and the enjeu social (social question) confronting his people make eminently good sense to Scott and me. Although I have focused on German more than French intellectual history, most of the authors and social critics whom Scott cites are for me familiar names. I agree with Scott that Éric Zemmour, a Moroccan Jew who has tried to revive the sense of French honor that he associates with the late General de Gaulle, illustrates the new identitarian French politics. So too does the iconoclastic novelist Michel Houellebecq, who, despite his shockingly erotic work, clearly loathes multiculturalism and despises French Islamophiles. Another figure in this Pleiades of intellectuals of the French right is Christophe Guilluy, who often sounds like the French Steve Bannon. In his books La France périphérique(2014) and Le crepuscule de la France d’en haut (2016), Guilluy comes to the defense of that 60 percent of the French population living on the “periphery,” that is, outside of metropolitan areas and the sprawling suburbs. These are the “les Francais de souche,” the true indigenous French, whom the globalist elites treat like human waste while they cut production costs by bringing in cheap labor from the Muslim Third World.

The useful idiots are all over the place, but that’s exactly what they are, mere stage extras. They are impressionable adolescents, Hollywood airheads, middle-aged women who want to “assert themselves,” perpetually incited racial minorities, and Muslim activists. Many of them can be mobilized at the drop of a pin to “march for tolerance,” however that term is interpreted by those who organize the march and by politicians, like Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi, who seek to increase their influence through well-prepared displays of “righteous indignation.” Please note that Schumer’s obstructionist tactics in the Senate, blocking or delaying cabinet nominees and threatening to shoot down Trump’s Supreme Court nominee, have been applied to the accompaniment of non-stop anti-Trump protests. Only a fool or unthinking partisan would believe these events are unrelated.

The useful idiots are all over the place, but that’s exactly what they are, mere stage extras. They are impressionable adolescents, Hollywood airheads, middle-aged women who want to “assert themselves,” perpetually incited racial minorities, and Muslim activists. Many of them can be mobilized at the drop of a pin to “march for tolerance,” however that term is interpreted by those who organize the march and by politicians, like Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi, who seek to increase their influence through well-prepared displays of “righteous indignation.” Please note that Schumer’s obstructionist tactics in the Senate, blocking or delaying cabinet nominees and threatening to shoot down Trump’s Supreme Court nominee, have been applied to the accompaniment of non-stop anti-Trump protests. Only a fool or unthinking partisan would believe these events are unrelated.

A

A

Flynn’s still highly readable

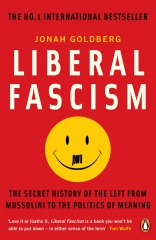

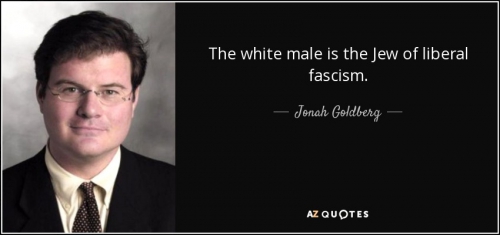

Flynn’s still highly readable  While New Deal critics tried to understand fascism in their time, today’s GOP propagandists do not try to understand anything about this interwar movement. They make their living by labeling the Democrats “fascists” and then identifying fascism and the Democrats with the Left. Jonah Goldberg’s best-selling

While New Deal critics tried to understand fascism in their time, today’s GOP propagandists do not try to understand anything about this interwar movement. They make their living by labeling the Democrats “fascists” and then identifying fascism and the Democrats with the Left. Jonah Goldberg’s best-selling

D

D

The book (translated into English as Atomized) tells us about the life of famous biologist Michel Djersinski, who mysteriously disappears in the twenty-first century after having plotted the path to a new level of human consciousness. Djersinski’s world i

The book (translated into English as Atomized) tells us about the life of famous biologist Michel Djersinski, who mysteriously disappears in the twenty-first century after having plotted the path to a new level of human consciousness. Djersinski’s world i

Paul Gottfried recently retired as Professor of Humanities at Elizabethtown College, PA. He is the author of

Paul Gottfried recently retired as Professor of Humanities at Elizabethtown College, PA. He is the author of

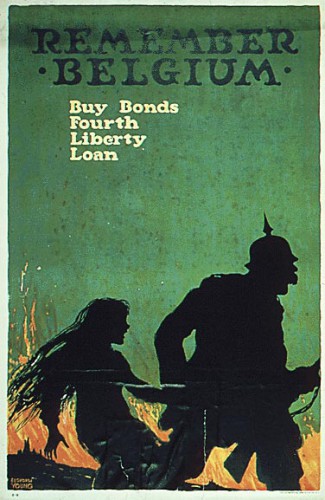

The success of neoconservative myth-mongering about World War One was brought home to me for the millionth time this weekend as I picked up our borough weekly

The success of neoconservative myth-mongering about World War One was brought home to me for the millionth time this weekend as I picked up our borough weekly