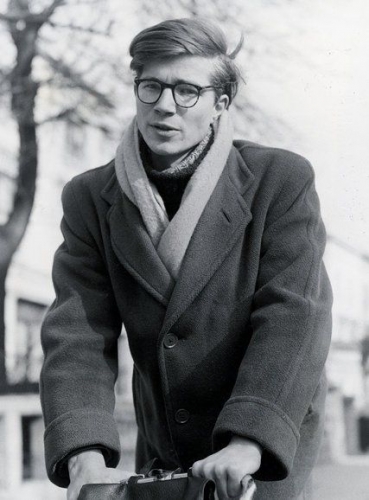

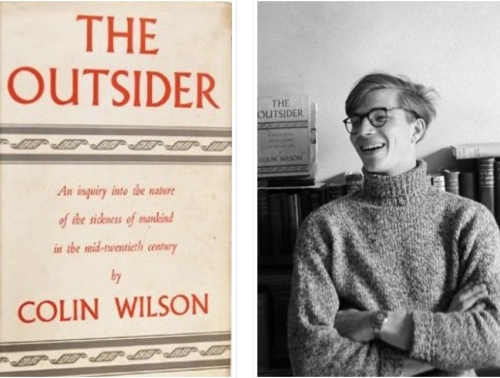

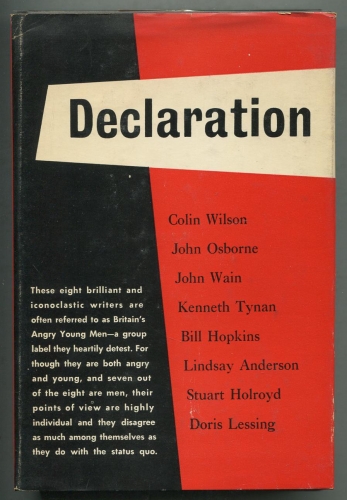

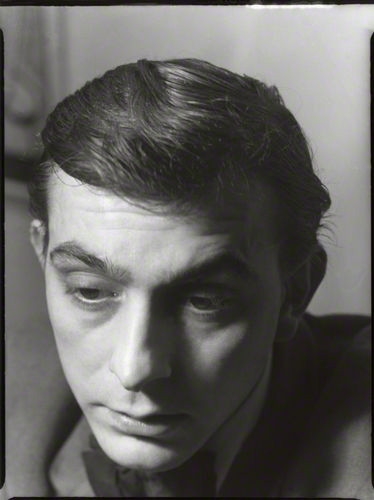

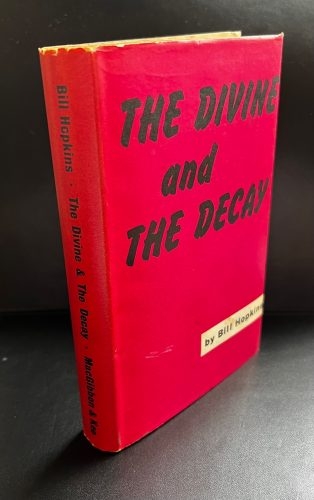

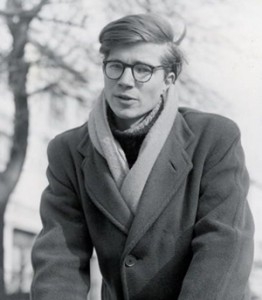

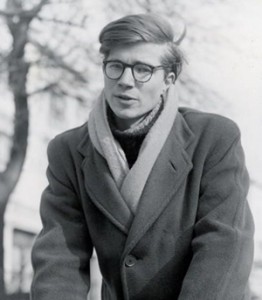

The following review was published in The European, a journal owned and published by Sir Oswald Mosley and his wife, Diana, between 1953 and 1959, in its February 1957 issue. It was signed only “European,” although it is now known this was a pseudonym used by Sir Mosley himself. Published only a short time after The Outsider [2] was first released in May 1956, it remains one of the best analyses of Colin Wilson [3]‘s most famous book, and was reprinted in the anthology Colin Wilson, A Celebration: Essays and Recollections (London: Woolf, 1988), which was edited by Colin’s bibliographer, Colin Stanley. The footnotes are Mosley’s own. The somewhat antiquated spelling and punctuation have been retained as they were in the original text.

It is always reassuring when men and things run true to form. It was, therefore, satisfactory that the silliest thing said in the literary year — the most frivolous and superficial in judgment — should emerge with the usual slick facility from the particular background of experience and achievement which has made Mr. Koestler the middle-brow prophet. He wrote of Mr. Colin Wilson’s remarkable book in the Sunday Times: “Bubble of the year: The Outsider (Gollancz), in which an earnest young man imparts his discovery to the world that genius is prone to Weltschmerz.”

Otherwise Mr. Wilson’s book had a very great success, and well deserved it. In fact, it was received with such a chorus of universal praise that it became almost suspect to those who believe that a majority in the first instance is almost always wrong, particularly when at this stage of a crumbling but still static society the opinion of the majority is so effectively controlled by the instruments of a shaken but yet dominant establishment. Why has a book so exceptional, and so serious, been applauded rather than accorded the “preposterous” treatment which English literary criticism reserved for such as Spengler? The first answer is that Mr. Wilson’s mind is very attractive, and his lucid style makes easy reading; the suggestion that this book is so difficult that everyone buys it but no one reads it, would brand the reading public as moronic if it had any vestige of truth. The second answer is that Mr. Wilson has as yet said nothing, and consequently cannot be attacked for the great crime of trying to “get somewhere”; somewhere new in thought, or worse still, somewhere in deed and achievement. What he has so far published is a fine work of clarification. A strangely mature and subtle mind has produced a brilliant synopsis of the modern mind and spirit. He does not claim to advance any solution, though he points in various directions where solutions may be found; “it is not my aim to produce a complete and infallible solution of the Outsider’s problem, but only to point out that traditional solutions, or different solutions, do exist”. No one could possibly yet guess where he is going, or what he may ultimately mean. He probably does not know himself; and, at his age, it is not a bad thing to be a vivid illustration of the old saying: “no man goes very far, who knows exactly where he is going”. What makes this book important is that it is a symptom and a symbol; a symptom of the present division between those who think and those who do; a symbol of the search in a world of confusion and menace by both those who think and those who do for some fresh religious impulse which can give meaning and direction to life. To achieve this, those who only do need sensitivity to receive a vision of purpose without which they are finally lost, while those who only think and feel require, in order to face life, the robustness and resolution which in the end again can only be given by purpose.

Mr. Wilson begins his “inquiry into the nature of the sickness of mankind in the twentieth century” at the effective point of the writers who have most influence in the present intellectual world. They are mostly good writers; they are not among the writers catering for those intellectuals who have every qualification except an intellect. They are good, some are very good: but at the end of it all what emerges? One of the best of these writers predicted that at the end of it all comes “the Russian man” described by Mr. Wilson as “a creature of nightmare who is no longer the homo sapiens, but an existentialist monster who rejects all thought”, As Hesse, the prophet of this coming, put it: “he is primeval matter, monstrous soul stuff. He cannot live in this form; he can only pass on”. The words “he can only pass on” seem the essence of the matter; this thinking is a chaos between two orders. At some point, if we are ever to regain sanity, we must regard again the first order before we can hope to win the second. It was a long way from Hellas to “the Russian man”; it may not be so far from the turmoil of these birth pangs to fresh creation. It is indeed well worth taking a look at the intellectual situation; where Europeans were, and where we are.

Mr. Wilson begins his “inquiry into the nature of the sickness of mankind in the twentieth century” at the effective point of the writers who have most influence in the present intellectual world. They are mostly good writers; they are not among the writers catering for those intellectuals who have every qualification except an intellect. They are good, some are very good: but at the end of it all what emerges? One of the best of these writers predicted that at the end of it all comes “the Russian man” described by Mr. Wilson as “a creature of nightmare who is no longer the homo sapiens, but an existentialist monster who rejects all thought”, As Hesse, the prophet of this coming, put it: “he is primeval matter, monstrous soul stuff. He cannot live in this form; he can only pass on”. The words “he can only pass on” seem the essence of the matter; this thinking is a chaos between two orders. At some point, if we are ever to regain sanity, we must regard again the first order before we can hope to win the second. It was a long way from Hellas to “the Russian man”; it may not be so far from the turmoil of these birth pangs to fresh creation. It is indeed well worth taking a look at the intellectual situation; where Europeans were, and where we are.

But who’er can know, as the long days go

That to live is happy, hath found his heaven.

wrote Euripides in the Bacchae,[1] [4] which to some minds is the most sinister and immoral of all Greek tragedies. For others these dark mysteries which were once held to be impenetrable contain the simple message that men do themselves great hurt if they reject the beauty which nature offers, a hurt which can lead to the worst horrors of madness. “Il lui suffit d’eclairer et de developper le conflict entre les forces naturelles et l’âme qui pretend se soustraire à leur empire” — wrote Gide in his Journal — “Je rencontrai les Bacchantes, au temps ou je me debattais encore contre l’enserrement d’une morale puritaine“. To anyone familiar with such thinking it is not surprising to find the dreary manias of neo-existentialism succeeding the puritan tradition.

Man denies at his risk the simple affirmation: “Shall not loveliness be loved for ever?” The Greeks, as Goethe saw them, felt themselves at home within “the delightful boundaries of a lovely world. Here they had been set; this was their appropriate place; here they found room for their energy, material and nourishment for their essential life.” And again he wrote: “feeling and thought were not yet split in pieces, that scarce remediable cleavage in the healthy nature of man had not yet taken place”. Goethe was here concerned with the early stages of the disease to whose conclusion Mr. Wilson’s book is addressed.

This union of mind and will, of intellect and emotion in the classic Greek, this essential harmony of man and nature, this at-oneness of the human with the eternal spirit evoke the contrast of the living and the dying when set against the prevailing tendencies of modern literature. For, as Mr. Wilson puts it very acutely: when “misery will never end” is combined with “nothing is worth doing”, “the result is a kind of spiritual syphillis that can hardly stop short of death or insanity”. Yet such writers are not all “pre-occupied with sex, crime and disease”, treating of heroes who live in one room because, apparently, they dare not enter the world outside, and derive their little satisfaction of the universe from looking through a hole in the wall at a woman undressing in the next room. They are not all concerned like Dostoievsky’s “beetle man” with life “under the floor boards” (a study which should put none of us off reading him as far as the philosophy of the Grand Inquisitor and a certain very interesting conversation with the devil in the Brothers Karamazof, which Mr. Wilson rightly places very high in the world’s literature). Many of these writers of pessimism, of destruction and death have a considerable sense of beauty. Hesse’s remarkable Steppenwolf found his “life had become weariness” and he “wandered in a maze of unhappiness that led to the renunciation of nothingness”; but then “for months together my heart stood still between delight and stark sorrow to find how rich was the gallery of my life, and how thronged was the soul of wretched Steppenwolf with high eternal stars and constellations . . . this life of mine was noble. It came of high descent, and turned, not on trifles, but on the stars.” Mr. Wilson well comments that “stripped of its overblown language,” “this experience can be called the ultimately valid core of romanticism — a type of religious affirmation”. And in such writing we can still see a reflection of the romantic movement of the northern gothic world which Goethe strove to unite with the sunlit classic movement in the great synthesis of his Helena. But it ends generally in this literature with a retreat from life, a monastic detachment or suicide rather than advance into such a wider life fulfilment. The essence is that these people feel themselves inadequate to life; they feel even that to live at all is instantly to destroy whatever flickering light of beauty they hold within them. For instance De Lisle Adam’s hero Axel had a lady friend who shot at him “with two pistols at a distance of five yards, but missed him both times.” Yet even after this dramatic and perfect illustration of the modern sex relationship, they could not face life : “we have destroyed in our strange hearts the love of life . . . to live would only be a sacrilege against ourselves . . .” “They drink the goblet of poison together and die in ecstasy.” All of which is a pity for promising people, but, in any case, is preferable to the “beetle man”, “under the floor boards”, wall-peepers, et hoc genus omne, of burrowing fugitives; “Samson you cannot be too quick”, is a natural first reaction to them. Yet Mr. Wilson teaches us well not to laugh too easily, or too lightly to dismiss them; it is a serious matter. This is serious if it is the death of a civilisation; it is still more serious if it is not death but the pangs of a new birth. And, in any case, even the worst of them possess in some way the essential sensitivity which the philistine lacks. So we will not laugh at even the extremes of this system, or rather way of thinking; something may come out of it all, because at least they feel. But Mr. Wilson in turn should not smile too easily at the last “period of intense and healthy optimism that did not mind hard work and pedestrian logic.” He seems to regard the nineteenth century as a “childish world” which presaged “endless changes in human life” so that “man would go forward indefinitely on ‘stepping stones of his dead self’ to higher things.” He thinks that before we “condemn it for short-sightedness”, ” we survivors of two world wars and the atomic bomb” (at this point surely he outdoes the Victorians in easy optimism, for it is far from over yet) “would do well to remember that we are in the position of adults condemning children”. Why? — is optimism necessarily childish and pessimism necessarily adult? Sometimes this paralysed pessimism seems more like the condition of a shell-shocked child. Health can be the state of an adult and disease the condition of a child. Of course, if serious Victorians really believed in “the establishment of Utopia before the end of the century”, they were childish; reformist thinking of that degree is always childish in comparison with organic thinking. But there are explanations of the difference between the nineteenth and the twentieth century attitude, other than this distinction between childhood and manhood. Spengler said somewhere that the nineteenth century stood in relation to the twentieth century as the Athens of Pericles stood in relation to the Rome of Caesar. In his thesis this is not a distinction between youth and age — a young society does not reach senescence in so short a period — but the difference between an epoch which is dedicated to thought and an epoch which has temporarily discarded thought in favour of action, in the almost rhythmic alternation between the two states which his method of history observes. It may be that in this most decisive of all great periods of action the intellectual is really not thinking at all; he is just despairing. When he wakes up from his bad dream he may find a world created by action in which he can live, and can even think. Mr. Wilson will not quarrel with the able summary of his researches printed on the cover of his book : “it is the will that matters.” And he would therefore scarcely dispute the view just expressed; perhaps the paradox of Mr. Wilson in this period is that he is thinking. That thought might lead him through and far beyond the healthy “cowboy rodeo” of the Victorian philosophers in their sweating sunshine, on (not back) to the glittering light and shade of the Hellenic world — das Land der Griechen mit der Seele suchen — and even beyond it to the radiance of the zweite Hellas. Mr. Wilson does not seem yet to be fully seized of Hellenism, and seems still less aware of the more conscious way of European thinking that passes beyond Hellas to a clearer account of world purpose. He has evidently read a good deal of Goethe with whom such modern thinking effectively begins, and he is the first of the new generation to feel that admiration for Shaw which was bound to develop when thought returned. But he does not seem to be aware of any slowly emerging system of European thinking which has journeyed from Heraclitus to Goethe and on to Shaw, Ibsen and other modems, until with the aid of modern science and the new interpretation of history it begins to attain consciousness.

This union of mind and will, of intellect and emotion in the classic Greek, this essential harmony of man and nature, this at-oneness of the human with the eternal spirit evoke the contrast of the living and the dying when set against the prevailing tendencies of modern literature. For, as Mr. Wilson puts it very acutely: when “misery will never end” is combined with “nothing is worth doing”, “the result is a kind of spiritual syphillis that can hardly stop short of death or insanity”. Yet such writers are not all “pre-occupied with sex, crime and disease”, treating of heroes who live in one room because, apparently, they dare not enter the world outside, and derive their little satisfaction of the universe from looking through a hole in the wall at a woman undressing in the next room. They are not all concerned like Dostoievsky’s “beetle man” with life “under the floor boards” (a study which should put none of us off reading him as far as the philosophy of the Grand Inquisitor and a certain very interesting conversation with the devil in the Brothers Karamazof, which Mr. Wilson rightly places very high in the world’s literature). Many of these writers of pessimism, of destruction and death have a considerable sense of beauty. Hesse’s remarkable Steppenwolf found his “life had become weariness” and he “wandered in a maze of unhappiness that led to the renunciation of nothingness”; but then “for months together my heart stood still between delight and stark sorrow to find how rich was the gallery of my life, and how thronged was the soul of wretched Steppenwolf with high eternal stars and constellations . . . this life of mine was noble. It came of high descent, and turned, not on trifles, but on the stars.” Mr. Wilson well comments that “stripped of its overblown language,” “this experience can be called the ultimately valid core of romanticism — a type of religious affirmation”. And in such writing we can still see a reflection of the romantic movement of the northern gothic world which Goethe strove to unite with the sunlit classic movement in the great synthesis of his Helena. But it ends generally in this literature with a retreat from life, a monastic detachment or suicide rather than advance into such a wider life fulfilment. The essence is that these people feel themselves inadequate to life; they feel even that to live at all is instantly to destroy whatever flickering light of beauty they hold within them. For instance De Lisle Adam’s hero Axel had a lady friend who shot at him “with two pistols at a distance of five yards, but missed him both times.” Yet even after this dramatic and perfect illustration of the modern sex relationship, they could not face life : “we have destroyed in our strange hearts the love of life . . . to live would only be a sacrilege against ourselves . . .” “They drink the goblet of poison together and die in ecstasy.” All of which is a pity for promising people, but, in any case, is preferable to the “beetle man”, “under the floor boards”, wall-peepers, et hoc genus omne, of burrowing fugitives; “Samson you cannot be too quick”, is a natural first reaction to them. Yet Mr. Wilson teaches us well not to laugh too easily, or too lightly to dismiss them; it is a serious matter. This is serious if it is the death of a civilisation; it is still more serious if it is not death but the pangs of a new birth. And, in any case, even the worst of them possess in some way the essential sensitivity which the philistine lacks. So we will not laugh at even the extremes of this system, or rather way of thinking; something may come out of it all, because at least they feel. But Mr. Wilson in turn should not smile too easily at the last “period of intense and healthy optimism that did not mind hard work and pedestrian logic.” He seems to regard the nineteenth century as a “childish world” which presaged “endless changes in human life” so that “man would go forward indefinitely on ‘stepping stones of his dead self’ to higher things.” He thinks that before we “condemn it for short-sightedness”, ” we survivors of two world wars and the atomic bomb” (at this point surely he outdoes the Victorians in easy optimism, for it is far from over yet) “would do well to remember that we are in the position of adults condemning children”. Why? — is optimism necessarily childish and pessimism necessarily adult? Sometimes this paralysed pessimism seems more like the condition of a shell-shocked child. Health can be the state of an adult and disease the condition of a child. Of course, if serious Victorians really believed in “the establishment of Utopia before the end of the century”, they were childish; reformist thinking of that degree is always childish in comparison with organic thinking. But there are explanations of the difference between the nineteenth and the twentieth century attitude, other than this distinction between childhood and manhood. Spengler said somewhere that the nineteenth century stood in relation to the twentieth century as the Athens of Pericles stood in relation to the Rome of Caesar. In his thesis this is not a distinction between youth and age — a young society does not reach senescence in so short a period — but the difference between an epoch which is dedicated to thought and an epoch which has temporarily discarded thought in favour of action, in the almost rhythmic alternation between the two states which his method of history observes. It may be that in this most decisive of all great periods of action the intellectual is really not thinking at all; he is just despairing. When he wakes up from his bad dream he may find a world created by action in which he can live, and can even think. Mr. Wilson will not quarrel with the able summary of his researches printed on the cover of his book : “it is the will that matters.” And he would therefore scarcely dispute the view just expressed; perhaps the paradox of Mr. Wilson in this period is that he is thinking. That thought might lead him through and far beyond the healthy “cowboy rodeo” of the Victorian philosophers in their sweating sunshine, on (not back) to the glittering light and shade of the Hellenic world — das Land der Griechen mit der Seele suchen — and even beyond it to the radiance of the zweite Hellas. Mr. Wilson does not seem yet to be fully seized of Hellenism, and seems still less aware of the more conscious way of European thinking that passes beyond Hellas to a clearer account of world purpose. He has evidently read a good deal of Goethe with whom such modern thinking effectively begins, and he is the first of the new generation to feel that admiration for Shaw which was bound to develop when thought returned. But he does not seem to be aware of any slowly emerging system of European thinking which has journeyed from Heraclitus to Goethe and on to Shaw, Ibsen and other modems, until with the aid of modern science and the new interpretation of history it begins to attain consciousness.

He is acute at one point in observing the contrasts between the life joy of the Greeks and the moments when their art is “full of the consciousness of death and its inevitability”. But he still apparently regards them as “healthy, once born, optimists,” not far removed from the modern bourgeois who also realises that life is precarious. He apparently thinks they did not share with the Outsider the knowledge that an “exceptional sense of life’s precariousness” can be “a hopeful means to increase his toughness”. The Greeks, of course, had not the advantage of reading Mr. Toynbee’s Study of History, which does not appear on a reasonably careful reading to be mentioned in Mr. Wilson’s book.

He is acute at one point in observing the contrasts between the life joy of the Greeks and the moments when their art is “full of the consciousness of death and its inevitability”. But he still apparently regards them as “healthy, once born, optimists,” not far removed from the modern bourgeois who also realises that life is precarious. He apparently thinks they did not share with the Outsider the knowledge that an “exceptional sense of life’s precariousness” can be “a hopeful means to increase his toughness”. The Greeks, of course, had not the advantage of reading Mr. Toynbee’s Study of History, which does not appear on a reasonably careful reading to be mentioned in Mr. Wilson’s book.

However, as Trevelyan[2] [5] puts it, Goethe followed them when he “firmly seized and plucked the nettle of Greek inhumanity, and treated it as the Greeks themselves had done, making new life and beauty out of a tale of death and terror”. Yet, in the continual contrast from which the Greeks derive their fulness of life : “healthy and natural was their attitude to death. To them he was no dreadful skeleton but a beautiful boy, the brother of sleep”. It is an attitude very different to Dostoievsky’s shivering mouse on the ledge, which Mr. Wilson quotes: . . . “someone condemned to death says or thinks an hour before his death, that if he had to live on a high rock, on such a narrow ledge that he’d only have room to stand, and the ocean, everlasting darkness, everlasting solitude, everlasting tempest around him, he yet remains standing in a square yard of space all his life, a thousand years, eternity, it were better to live so than die at once.” But is the attitude of the “once born Greek” so inferior to the possibly many times born ledge clinger? On the contrary, is not the former attitude a matter of common observation among brave men and the latter attitude a matter of equally common observation among frightened animals whose fear of death is not only pathetic but irrational in its exaggeration. Mr. Wilson’s view of the Greeks seems to rest in the Winckelmann Wieland stage of an enchanted pastoral symplicity. He has not yet reached Goethe’s point of horror when he realised the full complexities of the Greek nature and only emerged to a new serenity when, again in Trevelyan’s words, he realised: “they had felt the cruelty of life with souls sensitive by nature to pain no less than to joy. They had not tried to shut their eyes to suffering. They had used it, as all great artists must, as material for their art; but they had created out of it, not something that made the world more horrible to live in, but something that enriched man’s life and strengthened him to endure and to enjoy, by showing that new life, new beauty, new greatness, could grow even out of pain and death.

Jaeger[3] [6] quotes Pythagoras to express something of the same thought; “that which opposes, fits; different elements make the finest harmony ever”.

Were these “once born” people really much less adult than the Outsider in his understanding that “if you subject a man to extremes of heat and cold, he develops resistance to both”? Perhaps they even understood that if we subject ourselves to more interesting extremes we may learn to achieve Mr. Wilson’s desire (and how right he is in this) “to live more abundantly”. And Mr. Wilson certainly does not desire to rest in the Outsider’s dilemma; he is looking for solutions. In Hellas he may find something of a solution, and much more than that; the rediscovery of a direction which can lead far beyond even the Greeks.

As a sensitive and perceptive student of Nietzsche he is aware of Dionysus, but is not so fully conscious of the harmony achieved between the opposing tensions of Apollo and Dionysus. “Challenge and response” too, was more attractive in the Greek version; Artemis and Aphrodite had a charming habit of alternating as good and evil in a completely natural anticipation of Goethe’s Prologue in Heaven, which we shall later regard as the possible starting point of a new way of thinking, and of that modern writing of history which supports it with a wealth of detail. But we should first briefly consider Mr. Wilson’s view of Nietzsche and others who are rather strangely classified with him; it is a surprise at first to find him described as an existentialist, though in one sense it is quite comprehensible. For instance, Thierry Maulnier’s play Le Profanateur recently presented essentially Nietzschian thought in an existentialist form. But to confine Nietzsche to existentialism is to limit him unduly, even if we recognise, as the author points out, that definitions of existentialism have greatly varied in recent times, and also, as all can observe, that Nietzsche may be quoted in contradictory senses almost as effectively as the dominant faith of our time. The finer aspects of Nietzsche seem beyond this definition; for instance the passage in Zarathustra which culminates in the great phrase: seinen Willen will nun der Geist, seine Welt gewinnt sich der Weltverlorene, or again the harmony of mind and will in the lovely passage of Menschliches, Allzumenschliches which seems a direct antithesis of the currently accepted view of Existentialism: “The works of such poets — poets, that is, whose vision of man is exemplary — would be distinguished by the fact that they appear immune from the glow and blast of the passions. The fatal touch of the wrong note, the pleasure taken in smashing the whole instrument on which the music of humanity has been played, the scornful laughter and the gnashing of teeth, and all that is tragic and comic in the old conventional sense, would be felt in the vicinity of this new art as an awkward archaic crudeness and a distortion of the image of man. Strength, goodness, gentleness, purity, and that innate and spontaneous sense of measure and balance shown in persons and their actions . . . a clear sky reflected on faces and events, knowledge and art at one: the mind, without arrogance and jealousy dwelling together with the soul, drawing from the opposites of life the grace of seriousness, not the impatience of conflict: all this would make the background of gold against which to set up the real portrait of man, the.picture of his increasing nobleness.”[4] [7] But far more than a whole essay of this length would be needed to do justice to Mr. Wilson’s interpretation of Nietzsche and in particular, perhaps, to examine his possible over-simplification of the infinite complexities of the eternal recurrence. There is little enough space to cover the essential thinking of this remarkable book; and we must omit altogether a few of the more trivial little fellows who sometimes detain the author. Why, for instance, does he lose so much time with Lenin’s “dreadful little bourgeois”, who crowned the career of a super egotist with the damp surmise that the world could not long survive the pending departure of Mr. H. G. Wells? Here again Mr. Wilson is acute in linking Wells with greater figures like Kierkegaard in the opinion that “philosophic discussion was completely meaningless”. Kierkegaard was a “deeply religious soul” who found Hegel “unutterably shallow”. So he founded modern Existentialism with the remark: “put me in a system and you negate me — I am not a mathematical symbol — I am.” Is such an assertion of the individual against the infinite ” unutterably shallow”, or is it relieved from this suggestion by the depths of its egotism? Such a statement can really only be answered by the unwonted flippancy of Lord Russell’s·reply to Descartes’ “cogito ergo sum“; “but how do you know it is you thinking”? Kierkegaard concluded that you cannot live a philosophy but you “can live religion”; but the attempt of this pious pastor to live his religion did not restrain him from “violently attacking the Christian Church on the grounds that it had solved the problem of living its religion by cutting off its arms and legs to make it fit life.” All these tendencies in Kierkegaard seem to indicate a certain confusion of Existentialism with Perfectionism — from which exhypothesi it should surely be very remote — but certainly qualify him as father of the inherent dissidence of modern Existentialism, and, perhaps, inspired M. Sartre to confer on the Communist Party the same benefits which the founder’s assistance had granted to the Church. All this derives surely from that initial impulse of sheer anarchy with which he assailed the Hegelian attempt at order. “There is discipline in heaven”, as one of Mr. Wilson’s favourites remarks (also more competence to exercise it, we may add) and we are left in the end with a choice between Kierkegaard’s great “I am” and Hegel’s majestic symbol in his Philosophy of History concerning the conflicting forces of the elements finally blending in a divine harmony of order. Yes, it is good that it is so plain where it all began; such pious and respectable origin. After the initial revolt against all sense of order it is not a long journey from “I am” to Sartre’s “l’homme est une passion inutile“, and to his hero, Roquentin, who finds that “it is the rational element that pushes into nihilism” and that his “only glimpse of salvation” comes from a negro woman singing “Some of these days”; yes, they certainly got rid of Hegel, but “these days” scarcely belong to Kierkegaard. Yet when they have reached “the rock bottom of self contempt ” they need again ”something rhythmic, purposive;” so man cannot live, after all, by “I am” alone. Sartre wanted freedom from all this and found that “freedom is terror”, during one of his all too brief experiences of action. Mr. Wilson comments with rare insight: ” freedom is not simply being allowed to do what you like”; ” it is intensity of will, and it appears under any circumstances that limit man and arouse man to more life.” If you do not “claim this freedom” you “slip to a lower form of life”; at this point the author seems to reach the opposite pole to the original premise of the existentialist theory. He states his position in this matter in a particularly fine passage: “Freedom posits free will; that is self-evident. But will can only operate when there is first a motive. No motive, no willing . But motive is a matter of belief; you would not want to do anything unless you believed it possible and meaningful. And belief must be belief in the existence of something; that is to say, it concerns what is real. So ultimately freedom depends on the real. The Outsider’s sense of unreality cuts off his freedom at the roots. It is as impossible to exercise freedom in an unreal world as it is to jump while you are falling.” How much nearer to clarity, sanity and effective purpose is this thinking than Sartre’s “philosophy of commitment”, which is only to say that, “since all roads lead nowhere, it is as well to choose any of them and throw all the energy into it . . .” It was at this point no doubt that the Communist Party became the fortunate receptacle of the great “I am” in its flight from the nightmare of the “useless passion”, and a few existential exercises in “freedom” from self were provided for Mr. Sartre until a change of weather rendered such exercises temporarily too uncomfortable. But again, yet again, we must seek freedom from our own besetting sin of laughing too easily and lightly at serious searchers after truth, when they on occasion fall into ridiculous situations; as Aristotle remarked to Alexander when the King caught him in an embarrassing position: “Sire, you will observe the straits to which the passions can reduce even the most eminent minds.” Despite all the nonsense, there is much to be said for Sartre. He is a great artist, one of the greatest masters of the theatre in all time. It is to be hoped that Mr. Wilson will one day extend his study of him to include Le Diable et le Bon Dieu. It is not merely a narrow professional interest which makes us regard this play as his greatest work — the incidental fact that in the first act he presents some of us as others see us, and in the last act as we see ourselves — but the manner in which he reviews nearly the whole gamut of human experiences in the body of the play. It is when he ceases to think and as a sensitive artist simply records his diverse impressions of this great age in an almost entirely unconscious fashion, that Sartre becomes great; so in the end, he is the true Existentialist.

But Mr. Wilson moves far beyond Sartre in regarding the thinkers of an earlier period; notably Blake. At this point he recovers direction. The reader will find pages 225 to 250 among the most important of this book, but he must read the whole work for himself; this review is a commentary and an addendum, not a précis for the idle, nor a primer for those who find anything serious too difficult. The author advances a long way when he considers Blake’s “skeleton key” to a solution for those who “mistake their own stagnation for the world’s”. Here we reach realisation that the “crises of’living demand the active co-operation of intellect, emotions, body on equal terms”; contact is made here with Goethe’s Ganzheit, although it is not mentioned. “Energy is eternal delight” takes us a long way clear o the damp caverns of neo-existentialism and

But Mr. Wilson moves far beyond Sartre in regarding the thinkers of an earlier period; notably Blake. At this point he recovers direction. The reader will find pages 225 to 250 among the most important of this book, but he must read the whole work for himself; this review is a commentary and an addendum, not a précis for the idle, nor a primer for those who find anything serious too difficult. The author advances a long way when he considers Blake’s “skeleton key” to a solution for those who “mistake their own stagnation for the world’s”. Here we reach realisation that the “crises of’living demand the active co-operation of intellect, emotions, body on equal terms”; contact is made here with Goethe’s Ganzheit, although it is not mentioned. “Energy is eternal delight” takes us a long way clear o the damp caverns of neo-existentialism and

When thought is closed in caves

Then love shall show its root in deepest hell

brings us nearer to the thought of Euripides with which this essay began. To Blake the greatest crime was to “nurse unfulfilled desire”; he was not only an enemy of the repressive puritanism and of all nature-denying creeds, but realised their disastrous effect upon the human psyche. He sought consciously the harmony of mind and nature, the blessed state the Greeks found somewhere between Apollo and Dionysus.

The law that abides and changes not, ages long

The eternal and nature born — these things be strong

declare the chorus in the Bacchae in warning to those who deny nature in the name of morality or reason.

A strait pitiless mind

Is death unto godliness.

Yet the great nature urge is not the enemy of the intellect but its equipoise and inspiration, declares the Bacchanal.

Knowledge, we are not foes

I seek thee diligently;

But the world with a great wind blows,

Shining, and not from thee;

Blowing to beautiful things . . . .

It is when intellect becomes separate from nature and combats nature that the madness, “the vastation” descends; the mind seeks flight from life in the womb-darkness whence it came; the end is under the floor boards, and worse, far worse. When intellect fails in a frenzy of self denial and self destruction, life must begin again at the base. Then the Euripidean chorus declares

The simple nameless herd of humanity

Has deeds and faith that are truth enough for me.

When mind fails, life is still there; and begins again, always begins again. Did these “once born” Greeks really see less than some of the wall-peepers, less even than the more advanced types considered in this fascinating book? Wretched “Steppenwolf”, you had only to look over your shoulder to see more constellations than you had ever dreamt. And it was no junketing cowboy in a hearty’s rodeo who wrote.

Not to be born is past all prizing

But when a man has seen the light

This is next best by far, that with all speed

He shall go thither, whence he came.

No men ever had a deeper sense of the human tragedy than the Greeks; none ever faced it with such brilliant bravery or understood so well not only the art of grasping the fleeting, ecstatic moment, but of turning even despair to the enhancement of beauty. Living was yet great; they understood dennoch preisen; they did not “leave living to their servants”. Mr. Wilson in quoting Aristotle in the same sense as the above lines of Sophocles — “not to be born is the best thing, and death is better than life” — holds that “this view” lies at one extreme of religion, and that “the other extreme is vitalism”. He does not seem at this point fully to understand that the extremes in the Hellenic nature can be not contradictory but complementary, or interacting. The polarity of Greek thought was closely observed and finely interpreted by Nietzsche in diverse ways. But it was left to Goethe to express the more conscious thought beyond polarity in his Faust: the Prologue in Heaven:

No men ever had a deeper sense of the human tragedy than the Greeks; none ever faced it with such brilliant bravery or understood so well not only the art of grasping the fleeting, ecstatic moment, but of turning even despair to the enhancement of beauty. Living was yet great; they understood dennoch preisen; they did not “leave living to their servants”. Mr. Wilson in quoting Aristotle in the same sense as the above lines of Sophocles — “not to be born is the best thing, and death is better than life” — holds that “this view” lies at one extreme of religion, and that “the other extreme is vitalism”. He does not seem at this point fully to understand that the extremes in the Hellenic nature can be not contradictory but complementary, or interacting. The polarity of Greek thought was closely observed and finely interpreted by Nietzsche in diverse ways. But it was left to Goethe to express the more conscious thought beyond polarity in his Faust: the Prologue in Heaven:

The Lord speaks to Mephistopheles:

Des Menschen Thätigkeit kann allzuleicht erschlaffen

Er liebt sich bald die unbedingte Ruh;

Drum geb’ ich gern ihm den Gesellen zu,

Der reizt und wirkt, und muss, als Teufel, schaffen.

What is this but the definite statement that evil is the instrument of good? It is not only a better key to Faust than most of the tomes which have been written in analysis of this world masterpiece, but it is also the effective beginning of a new way of thinking. It was very obliging of Mr. Toynbee to collect so many facts in support of the thesis which becomes visible to any sentient mind in reading the first few pages of Faust, and his final intrusion of a personal opinion supported by belief rather than by fact detracts only slightly from his painstaking support for creative thought. “Challenge and Response” was born in Faust; and more, much more. Mr. Wilson moves towards this way of thinking on page 239 in the course of his study of Blake, and to us it is his most interesting moment. He writes “the whole was necessary” . . . “evolution towards God is impossible without a fall.” This passage follows the penetrating observation: “Yet it is the Outsider’s belief that life aims at more life, and higher forms of life” (our italics). At this point this interesting thinker and gifted writer reaches towards that decisive movement of European thought which began, perhaps, originally with Heraclitus and evolved through philosophers, prophets and poets, such as Goethe combined in his own genius, until it touched thinkers like Shaw and Ibsen in the modern age. This remarkable young man may end as the saint whom he suggests in his last line may be the Outsider’s goal, or worse, much worse, as just a success; yet the fact will remain that at this point he touched reality.

May we end with a few questions based on that doctrine of higher forms which has found some expression in this Journal and in previous writings? Is it not now possible to observe with reason and as something approaching a clearly defined whole, what has hitherto only been revealed in fitful glimpses to the visionary? What are the means of observation available to those who are not blessed with the revelation of vision? Are they not the thoughts of great minds which have observed the working of the divine in nature and the researches of modern science which appear largely to confirm them?

May we end with a few questions based on that doctrine of higher forms which has found some expression in this Journal and in previous writings? Is it not now possible to observe with reason and as something approaching a clearly defined whole, what has hitherto only been revealed in fitful glimpses to the visionary? What are the means of observation available to those who are not blessed with the revelation of vision? Are they not the thoughts of great minds which have observed the working of the divine in nature and the researches of modern science which appear largely to confirm them?

Is it not possible by following such thinking and such observation of science to arrive at a new religious impulse? Can we not now see the wholeness, the harmony and the purpose of life by a process of normal thought, even more surely than the sensitive artist in the ecstasy of vision and at least as surely as the revealed faiths which have been accorded to some? Has modern man not reached the point where he requires neither prophets nor priests to show him truth ? Can he not now open his eyes and see sufficient truth to guide him, in the thought and discovery of the human intellect during nearly 3000 years of striving by the human will toward the light? Is it not at least clear that life began in a very low form and has reached a relative height by a process which it is easier to believe is inspired than the subject of an almost incredible series of chances? Is it not clear that a persistent and, in the end, consistent, movement from lower to higher forms is the process and purpose of life? It is at least what has so far happened, if we regard the process over an appreciable period of time. And if this be the purpose it solves the problem of the individual; he has no duty and should have no purpose but to place himself at the disposal and to the service of that higher purpose. It is true that the divine work in nature during the movement from lower to higher forms is apparently subject to restriction and almost to paradox. The reckless, brutal waste of nature in experiment with types which fail, the agony and useless extinction of a suffering child without trace of purpose and with still less trace of kindness or of goodness, etc., all indicate some failure of power, or lack of direction, which are not easily explained by any process of thought limited to the confines of this world. Even these phenomena of fitful horror are, of course, explicable if men be more than once born, and various degrees of solipsistic explanation could also exist. But in the light of this world and its observed events they are admittedly not easily explained in terms of coherent, and certainly not of beneficent purpose. Yet is it really necessary to be able to explain every method of the process in order to observe the result of the process as a whole? Aristotle helps us again to some extent: “the process of evolution is for the sake of the thing finally evolved and not for the sake of the process.” While, too, we cannot explain all the apparent freaks of nature — freaks of seemingly gratuitous horror — we can now in considerable degree explain the method of nature which to a large extent contains a purpose for suffering. Primitive types simply do not move except under the impulse of necessity. There can in the beginning be no movement from lower to higher forms except under the stress of pain. But there can and should come a point in evolution when man moves forward by motive power of the fire within and not by pressure of the agony without.

At some point the spirit, the soul — call it what you will — is ignited by some spark of the divine and moves without necessity; yet, again it is a matter of common observation that this only occurs in very advanced types. In general it is only the “challenge” of adverse circumstance which evokes the “response” of movement to a higher state. Goethe expressed this thought very clearly in Faust by his concept of evil’s relationship to good; he also indicated the type where the conscious striving of the aspiring spirit replaces the urge of suffering in the final attainment of salvation: wer immer strebend sich bemüht, den können wir erlösen. In the early stages of the great striving all suffering, and later all beauty must be experienced and sensed; but to no moment of ecstasy can man say, verweile doch, du bist so schön until the final passing to an infinity of beauty at present beyond man’s ken. Complacency, at any point, is certainly excluded. So must it be always in a creed which begins effectively with Heraclitus and now pervades modern vitalism. The philosophy of the “ever living fire”, of the ewig werdende could never be associated with complacency. Still less can the more conscious doctrine of higher forms co-exist with the static, or with the illusory perfections of a facile reformism. Man began very small, and has become not so small; he must end very great, or cease to be. That is the essence of the matter. Is it true? This is a question which everyone must answer for himself after studying European literature which stretches from the Greeks to the vital thought of modern times and, also, the world thinking of many different climes and ages which in many ways and at most diverse points is strangely related. He should study, too, either directly or through the agency of those most competent to judge, the evolutionary processes revealed so relatively recently by modern biology and the apparently ever increasing concept of ordered complexity in modern physics. He must then answer two questions: the first is whether it is more likely than not that a purpose exists in life? — the second is whether despite all failures and obscurities the only discernable purpose is a movement from lower to higher forms? If he comes at length to a conclusion which answers both these questions with a considered affirmative, he has reached the point of the great affirmation. The new religious impulse which so many seek is really already here. We need neither prophets nor priests to find it for ourselves, although we are not the enemies but the friends of those who do. For ourselves we can find in the thought of the world the faith and the service of the conscious and sentient man.

At some point the spirit, the soul — call it what you will — is ignited by some spark of the divine and moves without necessity; yet, again it is a matter of common observation that this only occurs in very advanced types. In general it is only the “challenge” of adverse circumstance which evokes the “response” of movement to a higher state. Goethe expressed this thought very clearly in Faust by his concept of evil’s relationship to good; he also indicated the type where the conscious striving of the aspiring spirit replaces the urge of suffering in the final attainment of salvation: wer immer strebend sich bemüht, den können wir erlösen. In the early stages of the great striving all suffering, and later all beauty must be experienced and sensed; but to no moment of ecstasy can man say, verweile doch, du bist so schön until the final passing to an infinity of beauty at present beyond man’s ken. Complacency, at any point, is certainly excluded. So must it be always in a creed which begins effectively with Heraclitus and now pervades modern vitalism. The philosophy of the “ever living fire”, of the ewig werdende could never be associated with complacency. Still less can the more conscious doctrine of higher forms co-exist with the static, or with the illusory perfections of a facile reformism. Man began very small, and has become not so small; he must end very great, or cease to be. That is the essence of the matter. Is it true? This is a question which everyone must answer for himself after studying European literature which stretches from the Greeks to the vital thought of modern times and, also, the world thinking of many different climes and ages which in many ways and at most diverse points is strangely related. He should study, too, either directly or through the agency of those most competent to judge, the evolutionary processes revealed so relatively recently by modern biology and the apparently ever increasing concept of ordered complexity in modern physics. He must then answer two questions: the first is whether it is more likely than not that a purpose exists in life? — the second is whether despite all failures and obscurities the only discernable purpose is a movement from lower to higher forms? If he comes at length to a conclusion which answers both these questions with a considered affirmative, he has reached the point of the great affirmation. The new religious impulse which so many seek is really already here. We need neither prophets nor priests to find it for ourselves, although we are not the enemies but the friends of those who do. For ourselves we can find in the thought of the world the faith and the service of the conscious and sentient man.

Notes

[1] [8] Professor Gilbert Murray’s translation.

[2] [9] Goethe and the Greeks by Humphrey Trevelyan, Cambridge University Press.

[3] [10] Paideia, 3 vols, by Werner Jaeger.

[4] [11] Professor Heller’s translation in his book The Disinherited Mind (Bowes and Bowes).

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Le deuxième volume de la trilogie, récemment publié, L'homme sans ombre (Carbonio editore, 299 p., 16,50 euros) peut être lu et apprécié indépendamment du premier livre, étant un autre chapitre de la vie de l'écrivain Gérard Sorme, cette fois-ci centré sur le sexe : une sorte de "journal intime" comme le dit le sous-titre. Pour Sorme, le sexe est un élément d'inspiration pour ses histoires, afin d'élargir sa conscience, un peu comme à Londres dans les années 60 où l'on affirmait la consommation de drogues, et donc il s'engage à avoir une vie intense dans ce domaine et, dans un journal intime, il transcrit ses expériences, ses rencontres, les filles avec lesquelles il sort et ses pensées à leur sujet. Gertrude, Caroline, Madeleine, Charlotte, Mary, les femmes et les visages, les mots et les corps se succèdent jusqu'à ce qu'il rencontre et conquière Diana, une femme mariée à un musicien fou qui est un peu plus âgée qu'elle. Gérard tombe profondément amoureux.

Le deuxième volume de la trilogie, récemment publié, L'homme sans ombre (Carbonio editore, 299 p., 16,50 euros) peut être lu et apprécié indépendamment du premier livre, étant un autre chapitre de la vie de l'écrivain Gérard Sorme, cette fois-ci centré sur le sexe : une sorte de "journal intime" comme le dit le sous-titre. Pour Sorme, le sexe est un élément d'inspiration pour ses histoires, afin d'élargir sa conscience, un peu comme à Londres dans les années 60 où l'on affirmait la consommation de drogues, et donc il s'engage à avoir une vie intense dans ce domaine et, dans un journal intime, il transcrit ses expériences, ses rencontres, les filles avec lesquelles il sort et ses pensées à leur sujet. Gertrude, Caroline, Madeleine, Charlotte, Mary, les femmes et les visages, les mots et les corps se succèdent jusqu'à ce qu'il rencontre et conquière Diana, une femme mariée à un musicien fou qui est un peu plus âgée qu'elle. Gérard tombe profondément amoureux. Wilson dans Night Rites fait référence au crime et à la recherche de la définition mentale d'un jeu psychologique qui pourrait obséder le tueur en série. Au contraire, au centre du récit de L'Homme sans ombre, il n'y a pas vraiment que le sexe, comme les critiques et l'auteur lui-même voudraient nous le faire croire. Il y en a, bien sûr, mais avec une plus grande prépondérance de la magie. En fait, dans la première partie, Wilson déclare : "Je suis certain d'une chose : l'énergie sexuelle est aussi proche de la magie - du surnaturel - que les êtres humains en ont jamais fait l'expérience. Elle mérite une étude continue et attentive. Aucune étude n'est aussi profitable pour le philosophe. Dans l'énergie sexuelle, il peut observer le but de l'univers en action". Cette phrase, qui dans la réalité moderne et dans le Londres du Swinging des années 1960, était considérée comme l'exaltation des sens et de la luxure sexuelle comme la gratification du désir, renvoie en fait à un thème central de la magie : l'utilisation de la plus grande force existante - le sexe - pour accéder aux forces de l'Univers et plier les forces de la nature (mentionnée à plusieurs reprises par l'écrivain anglais) à sa volonté. Un enseignement qui est présent dans toutes les doctrines ésotériques de n'importe quelle partie du monde (Cf. Evola, Metafisica del sesso, Ed. Mediterranee ; Weininger, Sesso e carattere, Ed. Mediterranee, etc.). Mais le monde moderne n'interprète le sexe que dans une dimension consumériste et comme une source de plaisir physique, et c'est tout.

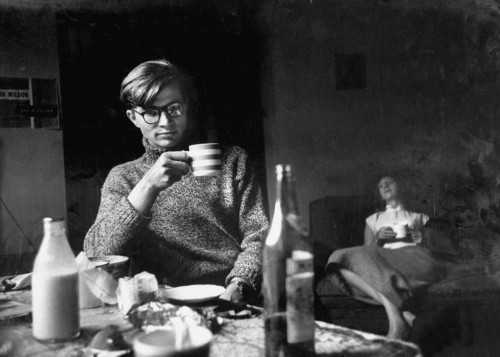

Wilson dans Night Rites fait référence au crime et à la recherche de la définition mentale d'un jeu psychologique qui pourrait obséder le tueur en série. Au contraire, au centre du récit de L'Homme sans ombre, il n'y a pas vraiment que le sexe, comme les critiques et l'auteur lui-même voudraient nous le faire croire. Il y en a, bien sûr, mais avec une plus grande prépondérance de la magie. En fait, dans la première partie, Wilson déclare : "Je suis certain d'une chose : l'énergie sexuelle est aussi proche de la magie - du surnaturel - que les êtres humains en ont jamais fait l'expérience. Elle mérite une étude continue et attentive. Aucune étude n'est aussi profitable pour le philosophe. Dans l'énergie sexuelle, il peut observer le but de l'univers en action". Cette phrase, qui dans la réalité moderne et dans le Londres du Swinging des années 1960, était considérée comme l'exaltation des sens et de la luxure sexuelle comme la gratification du désir, renvoie en fait à un thème central de la magie : l'utilisation de la plus grande force existante - le sexe - pour accéder aux forces de l'Univers et plier les forces de la nature (mentionnée à plusieurs reprises par l'écrivain anglais) à sa volonté. Un enseignement qui est présent dans toutes les doctrines ésotériques de n'importe quelle partie du monde (Cf. Evola, Metafisica del sesso, Ed. Mediterranee ; Weininger, Sesso e carattere, Ed. Mediterranee, etc.). Mais le monde moderne n'interprète le sexe que dans une dimension consumériste et comme une source de plaisir physique, et c'est tout. Un jeune homme en colère

Un jeune homme en colère

Little Gidding is a real place in Huntingdonshire and is closely associated with the English theologian Nicholas Farrar. Farrar was born in 1592 into a wealthy merchant family and he was intellectually precocious from an early age. After a short career in business and Parliament he left London and in 1625 moved to Little Gidding. At that time Little Gidding consisted of a run-down house and a chapel in a field. Farrar moved there with his mother, brother and sister, their children, and a few other people. About 30 people lived there and formed a close-knit religious community.

Little Gidding is a real place in Huntingdonshire and is closely associated with the English theologian Nicholas Farrar. Farrar was born in 1592 into a wealthy merchant family and he was intellectually precocious from an early age. After a short career in business and Parliament he left London and in 1625 moved to Little Gidding. At that time Little Gidding consisted of a run-down house and a chapel in a field. Farrar moved there with his mother, brother and sister, their children, and a few other people. About 30 people lived there and formed a close-knit religious community. Wilson notes, “It is true that the monastic temper is not a familiar one in the modern world and that, although millions of people may detest the routine of modern life and wish they could escape from it, they would hardly be willing to exchange it for the life of a monk.” But nonetheless, Ferrar had found one particular answer to the outsider’s problem: “he had set his own little corner of the world in order, and lived in that corner as if the rest of the world did not exist.”[1]

Wilson notes, “It is true that the monastic temper is not a familiar one in the modern world and that, although millions of people may detest the routine of modern life and wish they could escape from it, they would hardly be willing to exchange it for the life of a monk.” But nonetheless, Ferrar had found one particular answer to the outsider’s problem: “he had set his own little corner of the world in order, and lived in that corner as if the rest of the world did not exist.”[1]

Colin wrote two autobiographies: the first,

Colin wrote two autobiographies: the first,